Cachexia has a high prevalence in cancer patients, leading to reduced tolerance/response to treatment and decreased quality of life. Results from three global surveys presented herein demonstrate a definite need for increased awareness and educational initiatives to improve the knowledge and understanding of cancer cachexia among physicians in order to optimize patient outcomes.

Keywords: cancer cachexia, global survey, health care professional, weight loss, loss of appetite

Abstract

Background

Cachexia has a high prevalence in cancer patients and negatively impacts prognosis, quality of life (QOL), and tolerance/response to treatments. This study reports the results of three surveys designed to gain insights into cancer cachexia (CC) awareness, understanding, and treatment practices among health care professionals (HCPs).

Methods

Surveys were conducted globally among HCPs involved in CC management. Topics evaluated included definitions and synonyms of CC, diagnosis and treatment practices, and goals and desired improvements of CC treatment.

Results

In total, 742 HCPs from 14 different countries participated in the surveys. The majority (97%) of participants were medical oncologists or hematologists. CC was most frequently defined as weight loss (86%) and loss of appetite (46%). The terms loss of weight and decreased appetite (51% and 34%, respectively) were often provided as synonyms of CC. Almost half (46%) of the participants reported diagnosing CC and beginning treatment if a patient experienced a weight loss of 10%. However, 48% of the participants would wait until weight loss was ≥15% to diagnose CC and start treatment. HCPs also reported that 61%–77% of cancer patients do not receive any prescription medication for CC before Stage IV of disease is reached. Ability to promote weight gain was rated as the most important factor for selecting CC treatment. Key goals of treatment included ensuring that patients can cope with the cancer and treatment and have a QOL benefit. HCPs expressed desire for treatments with a more CC-specific mode of action and therapies that enhance QOL.

Conclusions

These surveys underscore the need for increased awareness among HCPs of CC and its management.

introduction

Cachexia is a debilitating condition with high occurrence in cancer patients, particularly in those with advanced disease [1, 2]; up to 20% of patients die as a result of cancer cachexia (CC) [3]. CC has been defined as a multifactorial syndrome characterized by muscle depletion, with or without loss of adipose tissue, which cannot be completely reversed by available treatments, leading to progressive functional derangements [4]. The pathophysiology of CC is characterized by reduced food intake and abnormal metabolism, which lead to a negative protein and energy balance [4]. The agreed-on diagnostic criteria for CC are a weight loss >5%, or a weight loss >2% in patients already showing depletion according to body mass index (BMI <20 kg/m2) or skeletal muscle mass [4].

It is well recognized that the influence of CC extends beyond weight loss, negatively impacting patients' psychological well-being, exercise capacity, quality of life (QOL), and tolerance and effectiveness of anticancer therapies, and is associated with systemic inflammation [5]. Nevertheless, CC is still frequently under-recognized, untreated, and considered inevitable for cancer patients [1, 6].

Despite this, there is a growing understanding of CC as a continuum that can progress through various stages: pre-cachexia, cachexia, and refractory cachexia [4]. A recent study examining classification models for CC highlighted the need to recognize the complete cachexia trajectory [7]. The authors have also proposed that cachexia should be considered a comorbidity of cancer [8]. These perspectives on CC have practical implications since they might favor early recognition, diagnosis, and therapeutic interventions. A clear distinction of pre-cachexia would allow treatments that can prevent/delay CC to be initiated as early as possible [9]. Since existing treatments are limited in their ability to treat CC, it is crucial to shift attention to improving early detection of nutritional and metabolic impairments that could lead to CC [5, 8–10]. In support of this, several studies have shown advantages of early nutritional counseling and intervention in cancer patients, in terms of treatment tolerance and clinical outcomes [11–15].

The aim of this study, composed of three global surveys, is to gain insights into the awareness, understanding, and treatment practices among health care professionals (HCPs) involved in CC management.

methods

surveys design and inclusion criteria

Three surveys were conducted among HCPs by Synovate Healthcare (now Ipsos Healthcare; Surveys 1 and 3) and Adelphi (Survey 2), between 2011 and 2012. The design of each study was developed according to the best market research practice. All questions were tested for understandability through an internal process among experts of the companies involved in the surveys' development. Since this was the first initiative in the field, the questions chosen for these surveys were not externally validated. Partial completion was not allowed or used for final analysis. Questions asked or discussed in the surveys and reported herein are described in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

survey 1

survey design

A 20-min questionnaire developed by a research team from Synovate Healthcare (now Ipsos Healthcare) with a background in social sciences consisted of multiple-choice questions. Participants from 13 different countries (Table 1) were selected, the majority via online panels that screened HCPs for inclusion (see inclusion criteria below); these participants completed the surveys online. The exception was Indonesia, where recruitment was carried out face to face by a local team of recruiters, and paper surveys were completed. The collected data were subject to verification.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Survey 1 (N = 541) | Survey 2 (N = 125) | Survey 3 (N = 76) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty, n (%) | |||

| Medical oncology/hematology | 541 (100) | 125 (100) | 55 (72.4) |

| Nutrition | – | – | 21 (27.6) |

| Country, n (%) | |||

| Brazil | 50 (9.2) | – | 13 (17.1) |

| Canada | 50 (9.2) | – | – |

| France | 50 (9.2) | – | 8 (10.5) |

| Germany | 50 (9.2) | – | 8 (10.5) |

| Italy | 50 (9.2) | – | 8 (10.5) |

| Indonesia | 20 (3.7) | – | – |

| Mexico | 51 (9.4) | – | – |

| Poland | 25 (4.6) | – | – |

| Romania | 25 (4.6) | – | – |

| Russia | 50 (9.2) | – | 10 (13.2) |

| Spain | 50 (9.2) | – | 8 (10.5) |

| Turkey | 20 (3.7) | – | 13 (17.1) |

| UK | 50 (9.2) | – | 8 (10.5) |

| USA | – | 125 (100) | – |

inclusion criteria

All participants had to have oncology as their primary specialty with more than 3 years of practicing experience, treat a minimum of 30 cancer patients each month, and be personally involved in the management and treatment of CC.

survey 2

survey design

An estimated 45-min Web-based questionnaire was developed by Adelphi Research, with multiple-choice and open-ended questions. Verified physician panels were used to recruit participants, all USA based (Table 1). Participants were screened for inclusion based on their responses to questions on standard research criteria (i.e. to ensure that there were no affiliations with pharmaceutical companies, health care, or governmental agencies) and treatment practices. Quantitative data were collected via an Internet survey, and invitations to participants were sent via an email that contained a secure, respondent-specific link to the survey. Responses were reviewed daily for quality. Qualitative data were collected via a telephone interview conducted by an Adelphi team member. Analysis of the responses was conducted by reviewing all responses and developing a framework specific to the survey, in which to categorize the responses. This was carried out by experienced market research professionals.

inclusion criteria

Participants had to have a primary specialty in either medical or hematologic oncology. They should have been in full-time practice for 3–25 years post-residency and see/treat at least 100 solid tumor cancer patients and at least 20 non-small-cell lung cancer patients each month. In the month before taking the survey, participants should have treated a minimum of 30 patients for cancer-associated weight loss, specifically with prescription medication.

survey 3

survey design

In-depth, 45-min interviews were developed by Ipsos Healthcare. Interviews were conducted in eight different countries (Table 1), the majority by telephone. Exceptions were Turkey and Russia, where the interviews were face to face. Participants were recruited via local offices and freelance recruiters for Ipsos Healthcare. Interviews were conducted by local office and freelance qualified moderators, and audio recorded. A code frame was developed and applied to the verbatim responses for each open-ended question. Each verbatim response was then analyzed by trained coders and assigned to the appropriate code.

inclusion criteria

Participants had to be qualified oncologists or nutritionists for at least 3 years. They also had to be personally involved in the management and treatment of CC patients.

statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 19. Frequencies were described, and the results were reported using descriptive statistics accounting for lack of response. For Survey 1, the closed data were analyzed at a total level, as well as by country. Frequencies and means (as appropriate) were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Data Collection software.

results

survey participation and respondents' characteristics

In Survey 1, ∼5550 HCPs, and in Survey 2, 514 HCPs were invited to participate; the number of participants invited for Survey 3 was not recorded. In total, 742 HCPs, from 14 different countries globally, fully completed the questionnaires (Survey 1, N = 541; Survey 2, N = 125; Survey 3, N = 76). As is customary with market research surveys, the overall response rate was low (10% for Survey 1 and 33% for Survey 2). Nevertheless, the actual number of respondents (N = 742) was sufficiently high to enable interpretation of current clinical practice and unmet educational needs. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The majority (97%) of the respondents were medical oncologists or hematologists.

definitions and synonyms of CC

When asked to provide a definition spontaneously, CC was defined most frequently as weight loss (86%) and loss of appetite (46%); over a quarter (27%) of HCPs provided the definition of muscle wasting/loss of body mass. When asked to spontaneously provide words that they considered to be synonymous with CC, participants most often used the terms loss of weight and decreased appetite (51% and 34%, respectively); over a quarter (28%) provided the term wasting/cancer wasting (supplemen-tary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

diagnosis and treatment practices

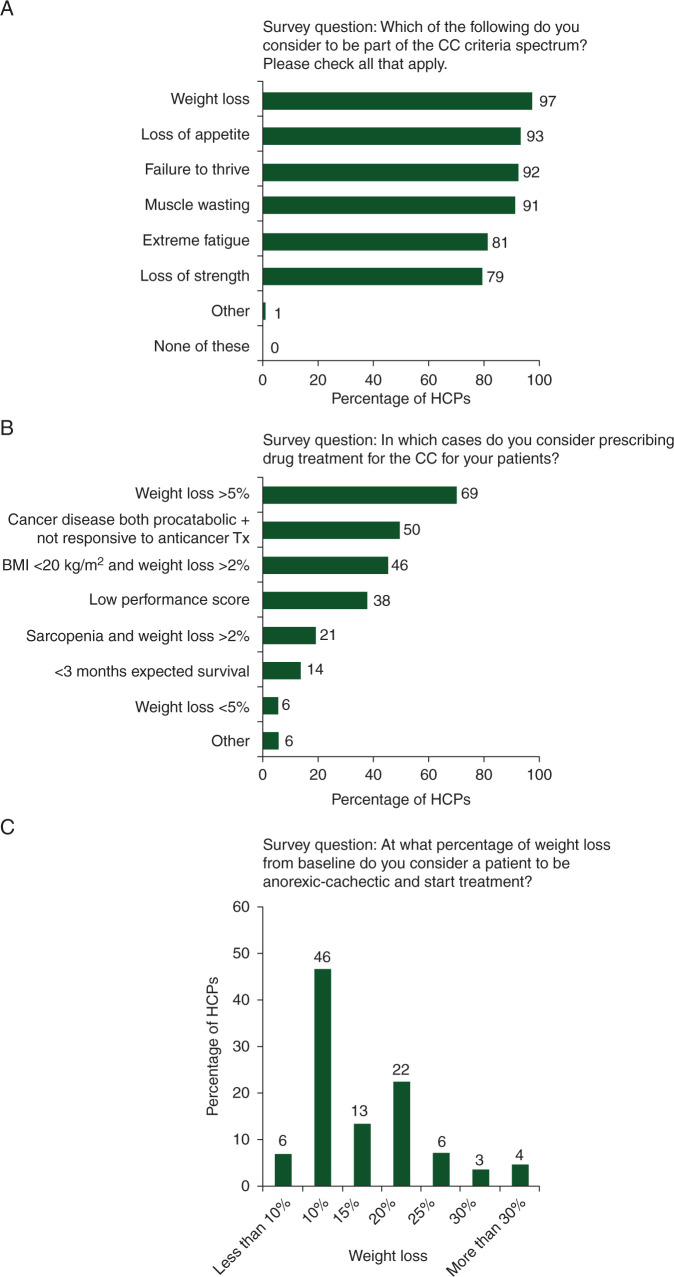

Symptoms most commonly considered to be part of the CC criteria spectrum were weight loss (97%), loss of appetite (93%), failure to thrive (92%), and muscle wasting (91%) (Figure 1A). The primary factor leading to the prescription of drug treatment of CC was weight loss >5% (69% of participants) (Figure 1B). Additionally, half of the HCPs would consider drug treatment of CC if the patient had cancer disease both procatabolic and not responsive to anticancer treatment (50% of participants), or a BMI of <20 kg/m2 plus a weight loss of >2% (46% of participants).

Figure 1.

Terms considered part of the CC spectrum (A), factors that prompted participants to consider drug treatment of CC (B), and weight loss from baseline at which a patient is considered to be anorexic-cachectic and treatment initiated (C). BMI, body mass index; CC, cancer cachexia; HCP, health care professional; Tx, treatment.

When HCPs were asked what percentage of weight loss from baseline they considered to be indicative of CC and would prompt them to initiate treatment (Figure 1C), almost half (46%) indicated a weight loss of 10%. However, 35% of participants responded that they would wait until weight loss was 15%–20%, and over 10% of participants would wait until weight loss was >25%.

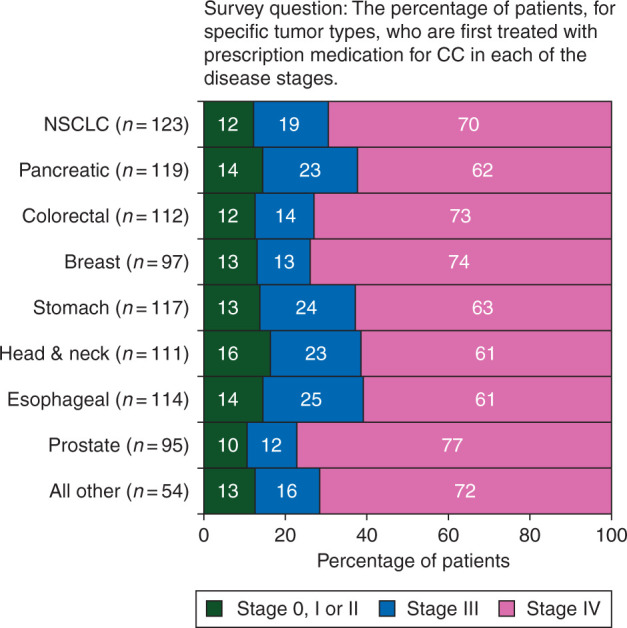

Regarding the disease stage at which patients are first treated for CC, responses revealed that 61%–77% of patients are only initiated on CC treatment with prescription medication at Stage IV disease, regardless of the tumor type (Figure 2). Prostate and breast cancers had the highest percentages of patients receiving initial CC treatment at Stage IV (77% and 74%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Tumor types treated for CC by stage. CC, cancer cachexia; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

goals and desired improvements of CC treatment

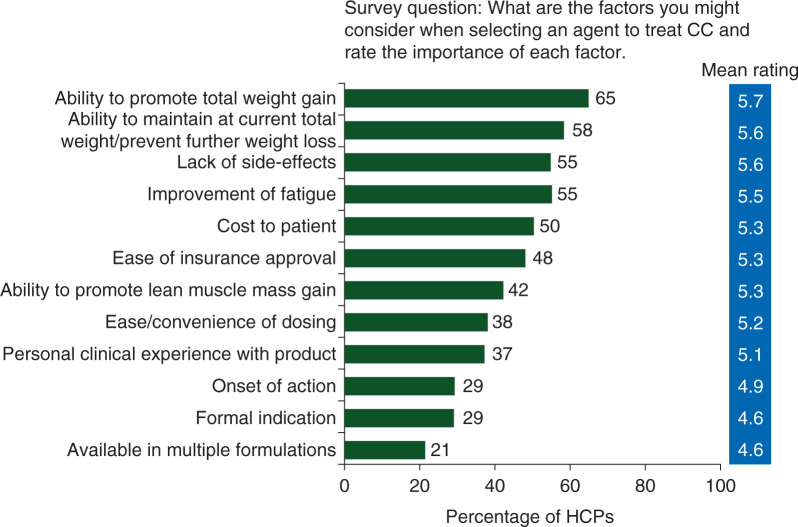

The ability to promote total weight gain was rated by participants as the most important factor in selecting a therapy for CC treatment (mean importance rating 5.7 on a 7-point scale where 1 = not at all important and 7 = extremely important). This was closely followed by the ability to maintain current total weight/prevent further weight loss, lack of side-effects, and improvement of fatigue (mean importance ratings: 5.6, 5.6, and 5.5, respectively) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Importance rating of factors determining the selection of CC treatment. Rating based on a 7-point scale: 1 = not at all important and 7 = extremely important. The percentages represent the number of HCPs giving an importance rating of 6 or 7. CC, cancer cachexia; HCP, health care professional.

The primary aims of HCPs when prescribing first-line treatment of CC were patient focused: enabling patients to improve or stabilize their weight, and ensuring that they can cope with cancer treatment and experience QOL improvements (Table 2). In response to what developments HCPs would like to see in the treatment of CC, participants desired more specific CC treatments; therapies that enhance multiple aspects of a patient's QOL (ease of administration, few side-effects, improve weight, appetite and energy levels, and mood lifting), and therapies that are able to be used early on, and/or preventively, providing rapid improvements.

Table 2.

Goals of the participants for treatment of CC patients

| Objectives of HCPs | Further details |

|---|---|

| Improve or stabilize weight |

|

| Improve QOL |

|

| Minimize side-effects |

|

| Improve nutritional status |

|

| Manage individual symptoms |

|

| Primary treatment and tumor response |

|

| Do nothing (no active interventions) |

|

CC, cancer cachexia; HCP, health care professional; QOL, quality of life.

discussion

CC is under-recognized and often inadequately managed by HCPs in oncology, with patients not receiving treatment that could improve clinical response, QOL, and ultimately survival [11]. Treatment is dependent on a variety of factors such as awareness of the condition, clinical practice within the specific therapeutic area, and resources available to dedicate time to assess symptoms and prescribe treatment [16, 17]. Our study provides insight into HCPs' attitudes toward nutritional and metabolic derangements, particularly oncologists who care for patients with the highest prevalence of malnutrition. This understanding is important to identify gaps in HCP knowledge and CC management, and also to develop strategies to assist HCPs in recognizing and effectively managing the condition.

Findings from the three global surveys reported herein demonstrate that the perception and clinical practices concerning CC vary among HCPs worldwide. There is still no clear and univocal concept of CC, although responses highlight that it is mainly perceived to be associated with weight loss and loss of appetite. Weight loss was also most frequently regarded as a symptom of CC, with the majority of participants in Survey 1 considering a weight loss of >5% to be the primary factor leading to the prescription of drug treatment of CC. Survey 1 covered 13 different countries across Europe, North America, and Australasia. Conversely, 48% of HCPs in Survey 2, who were all USA based, would wait for a weight loss of ≥15% before initiating treatment. Additionally, around two-thirds of cancer patients do not receive any CC prescription medication before the disease reaches Stage IV. These results suggest that while HCPs may be aware that weight loss and loss of appetite are consequences of cancer, there is a failure to recognize CC as a negative prognostic factor. Patients remain undiagnosed until late in the course of their disease, when the impact of CC on both QOL and treatment outcomes may have already been substantial.

While the understanding of the multifactorial pathogenesis of CC and its detrimental impact is improving, this knowledge still needs to be shared more widely and applied in clinical practice. The lack of nutrition studies during training translates into a limited understanding of the impact of nutritional status on treatment outcomes. With the focus shifting toward the importance of early intervention, increasing HCPs' understanding of the role of nutrition in cancer prognosis is important. A recent position paper of the European School of Oncology Task Force [5] highlights the need for a multimodal approach, including nutritional support and novel therapeutic agents, when managing malnutrition and CC. We have also recently proposed the ‘parallel pathway’, which encompasses a multiprofessional and multimodal approach to ensure that cancer patients receive appropriate and continuous nutritional and metabolic supports [9].

Another possible factor leading to suboptimal CC management is the lack of awareness of simple tools to identify patients who have symptoms of CC (e.g. standardized tools for body weight loss and appetite). A recent survey [18] demonstrated an urgent need for standardized symptom assessment to identify patients who are at risk earlier in the course of the condition. Although this was a small study, there is considerable interest in adopting a brief symptom assessment tool.

Furthermore, a study that scrutinized over 140 000 Web pages of various international oncology societies for guidelines on CC reported that global CC awareness appears to be extremely low [19]. Only a few (10/275) of the identified oncology societies provided guidelines, and of these, only 6 were for physicians, including the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative [20]. There is, therefore, a need for improved availability and effective dissemination of the most updated international clinical practice guidelines.

The strengths of this study include the large number of survey participants, comprising a good representation of HCPs treating CC patients, and its multinational nature. Outcomes can therefore be taken as a ‘real-world’ representation and can potentially inform the development of educational initiatives for HCPs and updates to current treatment guidelines. Conversely, the most relevant limitation of the study is that these are self-reported data, which could contain a bias in the responses. An additional limitation is the low response rate, often seen in market research, and may be a result of several factors including lack of enthusiasm for online surveys, current workload, and general interest in a topic. Other study drawbacks relate to the questions being presented differently in the three surveys and responses not always being grouped into country-specific responses. As such, we were unable to directly compare similarities and differences in results between the surveys or to make comparisons between countries. Nevertheless, the aim of the surveys was to provide an overall representation of treatment practices, and considering the large number of HCPs involved, data from each survey remain reliable in the authors' opinion. Future studies of actual HCPs' practices are warranted, to provide greater insights into unmet needs of CC management in the clinical setting.

This study underscores the need for increased awareness of CC and its management. Effective dissemination of current guidelines may help establish the criteria for CC diagnosis and treatment, and future guidelines should emphasize the importance of recognizing and treating CC at an earlier stage. Efforts should focus on identifying barriers and knowledge gaps, and tailoring educational initiatives to meet HCPs' needs. Additionally, providing effective, concise, and clinically relevant nutritional and metabolic guidelines to oncology trainees is vital.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the HCPs for their participation in these surveys. The authors also wish to thank Eva Polk, PhD, CMPP, Siddharth Mukherjee, PhD, and Delyth Eickermann, PhD, (TRM Oncology, The Hague, The Netherlands), for their medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

funding

The surveys described in this manuscript, carried out by Synovate Healthcare (now Ipsos Healthcare and Adelphi), were supported by an unrestricted educational grant provided by Helsinn Healthcare SA, Lugano, Switzerland and Helsinn Therapeutics, Inc. (US), Iselin, NJ, USA (no grant number applied). Editorial and medical writing assistance was funded by Helsinn Healthcare SA.

disclosure

The authors participated in data analysis and independently interpreted the data and directed manuscript content and development. This manuscript reports and discusses results from a survey sponsored by Helsinn. The authors have no further disclosures and no conflict of interest with the companies involved in performing and supporting the surveys.

references

- 1.Sun L, Quan XQ, Yu S. An epidemiological survey of cachexia in advanced cancer patients and analysis on its diagnostic and treatment status. Nutr Cancer 2015; 67: 1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Haehling S, Anker SD. Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: facts and numbers – update 2014. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014; 5: 261–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argilés JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, López-Soriano FJ. Cancer cachexia: understanding the molecular basis. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aapro M, Arends J, Bozzetti F et al. Early recognition of malnutrition and cachexia in the cancer patient: a position paper of a European School of Oncology Task Force. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1492–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanchieri C. Cachexia in cancer: is it treatable at the molecular level? J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102: 1694–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum D, Stene GB, Solheim TS et al. Validation of the Consensus-Definition for Cancer Cachexia and evaluation of a classification model — a study based on data from an international multicentre project (EPCRC-CSA). Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muscaritoli M, Molfino A, Lucia S, Rossi Fanelli F. Cachexia: a preventable comorbidity of cancer. A T.A.R.G.E.T. approach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015; 94: 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muscaritoli M, Molfino A, Gioia G, Laviano A, Rossi Fanelli F. The “parallel pathway”: a novel nutritional and metabolic approach to cancer patients. Intern Emerg Med 2011; 6: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muscaritoli M, Bossola M, Aversa Z, Bellantone R, Rossi Fanelli F.. Prevention and treatment of cancer cachexia: new insights into an old problem. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paccagnella A, Morello M, Da Mosto MC et al. Early nutritional intervention improves treatment tolerance and outcomes in head and neck cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18: 837–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes BG, Jain VK, Brown T et al. Decreased hospital stay and significant cost savings after routine use of prophylactic gastrostomy for high-risk patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy at a tertiary cancer institution. Head Neck 2013; 35: 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huhmann MB, August DA. Nutrition support in surgical oncology. Nutr Clin Pract 2009; 24: 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Meij BS, Langius JA, Smit ET et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids affect the nutritional status of patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer during multimodality treatment. J Nutr 2010; 140: 1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Liu BL, Shang B et al. Nutrition support in surgical patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 1779–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper C, Burden ST, Cheng H, Molassiotis A. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015; 6: 99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millar C, Reid J, Porter S. Healthcare professionals’ response to cachexia in advanced cancer: a qualitative study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2013; 40: E393–E402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Fabbro E, Jatoi A, Davis M et al. Health professionals’ attitudes toward the detection and management of cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome, and a proposal for standardized assessment. J Community Support Oncol 2015; 13: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauri D, Tsiara A, Valachis A et al. Cancer cachexia: global awareness and guideline implementation on the web. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radbruch L, Elsner F, Trottenberg P et al. Clinical practice guidelines on cancer cachexia in advanced cancer patients with a focus on refractory cachexia. 2010; http://www.epcrc.org/getpublication2.php?id=ternkkdsszelxevzgtkb (8 January 2016, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.