Addition of panitumumab to adjuvant chemoradiation is tolerable and provides promising clinical acivity for high risk, resected head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Keywords: panitumumab, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, clinical trial, cisplatin chemoradiotherapy

Abstract

Background

Treatment intensification for resected, high-risk, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is an area of active investigation with novel adjuvant regimens under study. In this trial, the epidermal growth-factor receptor (EGFR) pathway was targeted using the IgG2 monoclonal antibody panitumumab in combination with cisplatin chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in high-risk, resected HNSCC.

Patients and methods

Eligible patients included resected pathologic stage III or IVA squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, hypopharynx, or human-papillomavirus (HPV)-negative oropharynx, without gross residual tumor, featuring high-risk factors (margins <1 mm, extracapsular extension, perineural or angiolymphatic invasion, or ≥2 positive lymph nodes). Postoperative treatment consisted of standard RT (60–66 Gy over 6–7 weeks) concurrent with weekly cisplatin 30 mg/m2 and weekly panitumumab 2.5 mg/kg. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

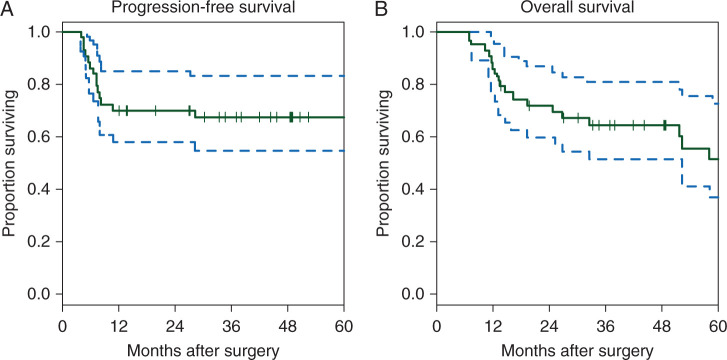

Forty-six patients were accrued; 44 were evaluable and were analyzed. The median follow-up for patients without recurrence was 49 months (range 12–90 months). The probability of 2-year PFS was 70% (95% CI = 58%–85%), and the probability of 2-year OS was 72% (95% CI = 60%–87%). Fourteen patients developed recurrent disease, and 13 (30%) of them died. An additional five patients died from causes other than HNSCC. Severe (grade 3 or higher) toxicities occurred in 14 patients (32%).

Conclusions

Intensification of adjuvant treatment adding panitumumab to cisplatin CRT is tolerable and demonstrates improved clinical outcome for high-risk, resected, HPV-negative HNSCC patients. Further targeted monoclonal antibody combinations are warranted.

Registered clinical trial number

introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth leading incident cancer worldwide [1] and the 5-year overall survival (OS) remains <50% despite advances in multimodal therapy over the past two decades [2]. The addition of cisplatin chemotherapy to the management of locally advanced HNSCC has been established with two randomized trials demonstrating significant benefit with the addition of cisplatin to postoperative radiotherapy (RT) [3, 4]. Despite the advancement of new radiation techniques and the addition of chemotherapy, a substantial risk of local recurrence, second primary tumors, and distant metastatic disease remains, necessitating integration of other treatment modalities such as targeted therapy. The epidermal growth-factor receptor (EGFR) has been identified as an oncogene and therapeutic target in HNSCC [5]. EGFR is overexpressed in 80%–90% of HNSCC, the highest frequency among solid tumors, with expression levels correlating with worse patient outcome [6, 7]. Cetuximab, a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against EGFR, demonstrated improvement in locoregional control and overall survival in locally advanced HNSCC in combination with RT [8] and is also indicated for use in combination with chemotherapy in first line therapy for recurrent/metastatic settings [9]. RTOG 0234 compared concurrent CRT and cetuximab in the postoperative treatment of patients with HNSCC with high-risk pathologic features, showing an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with controls [10]. Though studies demonstrated the safety of cetuximab when added to RT and in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, hypersensitivity reactions were observed. Panitumumab, a fully human, IgG2 anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of colon cancer [11], holds the potential for similar activity in this population with possibly lower toxicities and cross-reactions. In this study, we investigated the addition of panitumumab to standard adjuvant cisplatin CRT in patients with high-risk, resected HNSCC.

patients and methods

clinical trial eligibility criteria

The University of Pittsburgh protocol 06–120 was approved by the Institutional Review Board and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00798655). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to study entry. Key inclusion criteria included: pathologically staged HNSCC, stage III/IVa (AJCC 6th edition) of the oral cavity, larynx, or pharynx (HPV-negative) status post curative-intent surgical resection without gross residual tumor and with ≥1 high-risk features (margins <1 mm, extracapsular extension (ECE), perineural or angiolymphatic invasion, or ≥2 positive lymph nodes); no prior chemotherapy, biologic/targeted therapy, or radiation therapy; ≤7 weeks between surgery and initiation of radiotherapy; age ≥18 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) 0–1; adequate hematologic reserve and end organ function. Key exclusion criteria included: significant history of uncontrolled cardiac disease significant baseline neurologic deficits that would preclude use of platinum chemotherapy, pregnant women, prior severe infusion reaction to a human monoclonal antibody. Prior invasive malignancies were excluded unless DFS ≥3 years.

study treatment

Following surgery with curative intent, eligible patients were treated with standard RT (200 cGy/day for 6–7 weeks) concurrent with weekly cisplatin (30 mg/m2 intravenously) plus weekly panitumumab (2.5 mg/kg intravenously), the phase I maximum tolerated dose established as monotherapy in patients with advanced solid malignancies [11]. No dose reduction of cisplatin was permitted; however, carboplatin area-under-the-curve (AUC) of 1.5 could be substituted for cisplatin if patient developed cisplatin-associated intolerable toxicities as specified in the protocol. Two levels of dose reduction for panitumumab were permitted for tolerability (2 and 1.5 mg/kg). Panitumumab administration was not held for known cisplatin-related toxicities.

assessment of toxicity and response

Patients were assessable for response and survival analysis if they had received at least one dose of panitumumab. Toxicity was assessed at each visit, and adverse events (AE) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. Panitumumab administration was held for skin- or nail-related toxicities that required the use of narcotics or systemic steroids, intravenous antibiotics, or surgical debridement, grade III/IV diarrhea or anemia, grade 4 thrombocytopenia. Permanent dose reduction for panitumumab was required for grade 4 radiation mucositis/dysphagia or dermatitis.

sample collection and analysis

Ten milliliters of whole blood were collected at baseline and at 8 weeks post-panitumumab-CRT for serum cytokine measurements. Blood was allowed to clot for 15–30 min at room temperature, and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10–15 min to separate out serum, which was stored at −80°C. A standard calibration curve was generated by serial dilutions of recombinant cytokine. Cytokine concentrations of epidermal growth-factor (EGF) and transforming growth-factor beta (TGF-β) in patient serum were quantified using commercially available quantitative sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Quantikine;R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

statistical considerations

The study incorporated a single-arm phase II design of open-label panitumumab administered in combination with standard radiotherapy and weekly cisplatin. The intent was to ascertain whether the addition of panitumumab to standard concurrent cisplatin and radiotherapy improved efficacy of cisplatin and radiotherapy alone. The primary endpoint for efficacy was progression-free survival (PFS) at 2 years from the date of surgery. Postoperative disease recurrence was considered evidence of disease progression. The study was designed to detect whether the addition of panitumumab would increase the 2-year probability of PFS to 70% using the assumption that postoperative radiation and cisplatin alone would result in PFS of 50%. Forty-three evaluable patients were required to allow 90% power for a level 0.10 one-sided one sample exponential test to detect improvement from 50% to 70%. PFS was defined as the interval from date of potentially curative surgical resection to documented clinical or radiographic progression of disease, or death from disease. Only evaluable patients were included in the analyses of efficacy and toxicity.

The Kaplan–Meier method with Greenwood confidence intervals was used to estimate PFS and OS of the study population.

Secondary endpoints were to estimate OS, toxicity rates, and assessment of biomarker correlation with PFS. The adverse events profiles of each patient were summarized by grade, duration, and frequency. Differences between pre-treatment and week 8 levels of serum cytokines were tested with the signed rank test. The association between baseline and week 8 changes in cytokine levels was estimated with proportional hazards regression. In addition, series of five baseline tissue protein measurements were tested for association with progression-free survival with proportional hazards regression. At most only half of patient tumor samples were available and differences in patients with and without available tissue samples were examined for contrasts with recursive partitioning.

results

study population characteristics and treatment delivery

A total of 46 patients were enrolled from October 2007 through September 2013. Patients were followed for a minimum of 2 years after the last accrual and time-to-event analysis was up-to-date as of November 2015. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Eighty-two percent of patients enrolled were male, and the median age was 58 years (range 23–81). Forty-four patients received at least one dose of panitumumab and were evaluable for analysis, and 37 patients (84%) received all 7 planned doses of panitumumab (range 1–7 cycles). Thirty patients (68%) completed all 7 doses of cisplatin and panitumumab, and 95% of patients received at least 60 Gy of radiation therapy (range 16–70 Gy received). The median dose of radiation received was 64 Gy. Five patients (11%) experienced delays in radiation, range 1–21 days, and all of those patients received a total dose >60 Gy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 44)

| Characteristic | Number (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 58 |

| Range | 23–81 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 (82%) |

| Female | 8 (18%) |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 5 (11%) |

| T2 | 9 (20%) |

| T3 | 10 (23%) |

| T4 | 20 (46%) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 7 (16%) |

| N1 | 9 (20%) |

| N2 | 28 (64%) |

| Lymph node involvement | |

| ≥5 | 12 (27%) |

| Clinical stage | |

| III | 6 (14%) |

| IV | 38 (86%) |

| Primary site | |

| Oral cavity | 32 (73%) |

| Oropharynx | 1 (2%) |

| Hypopharynx | 2 (5%) |

| Larynx | 9 (20%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 31 (70%) |

| 1 | 13 (30%) |

| High-risk features | |

| Positive margins | 3 (7%) |

| Angiolymphatic invasion | 11 (25%) |

| Perineural invasion | 22 (50%) |

| Extracapsular extension (ECE) | 23 (52%) |

| Two or more positive lymph nodes | 28 (64%) |

primary endpoint: PFS

Median follow-up for 30 patients without disease progression was 49 months (range 12–90 months). Fourteen patients had disease recurrence. The estimated probability of PFS at 2 years was 70% (95% CI 58–85; Figure 1A). The median PFS in this study was not reached. Note that the estimate of PFS considered five patients dying without disease progression as censored. The observed outcome was compared with the pre-specified null hypothesis with a one-tailed one sample exponential test and verified with a one sample log-rank test. Both test results yielded P < 0.0001. The 3-year PFS was 68% (90% CI = 57%–81%)/(95% CI = 55%–83%). Median PFS was not reached for this trial.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in months.

secondary endpoints

The estimated probability of 2-year OS was 72% (CI 60%–87%; Figure 1B). The 3-year OS was 65% (90% CI = 54%–78%)/(95% CI = 52%–81%), with median OS not reached. At time of study completion, a total of 18 patients had died, 13 from disease and 5 from other causes. These included liver cirrhosis, pneumonia/bacteremia, COPD and cardiopulmonary arrest, occurring between 24 and 56 months after completion of therapy.

safety

Treatment-related toxicities are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 14 patients (32%) experienced grade ≥3 toxicity. Five patients (11%) required delay in RT, and 2 patients (5%) did not complete RT due to adverse events (mucositis). No treatment-related deaths were reported. The most common grade 4 toxicities were lymphopenia (18%) and mucositis (5%). One patient was hospitalized for psychosis, which is not known to be a direct side-effect of panitumumab, and was able to complete radiation. Gastrostomy tube placement was performed prophylactically prior to chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in 19 patients (43%), and 8 additional patients (18%) required placement during adjuvant therapy. Of the total 37 (84%) patients who had gastrostomy tube placed, only 3 (7%) required feeling tube long term (>1 year).

Table 2.

Grades 3 and 4 toxicities of 44 patients accrued to the trial

| Toxicity | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Mucositis | 16 (36%) | 2 (5%) |

| Lymphopenia | 13 (30%) | 8 (18%) |

| Hyponatremia | 11 (25%) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 9 (20%) | 2 (5%) |

| Dysphagia | 8 (18%) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 7 (16%) | 2 (5%) |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 6 (14%) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 5 (11%) | 0 |

| Rash | 4 (9%) | 0 |

| Neutropenic fever | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Infection | 3 (7%) | 0 |

| Anemia | 4 (9%) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 (7%) | 1 (2%) |

| Transaminitis | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

| Troponin elevation | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Psychosis | 0 | 1 (2%) |

aNo other grade 4 toxicities reported. Additional grade 3 toxicities reported in <5% of patients.

correlative studies

Primary surgical tissue was evaluated for possible biomarker associations with five proteins measured, including STAT1, STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), pSTAT1Y, and pSTAT1S. Resection specimens for analysis were only available for 22 patients (50%) enrolled in the trial. There were no differences in levels found between the groups of patients with and without tissue, respect to gender, surgical margin status, AJCC stage of disease, cycles of panitumumab received, disease site, or ECE (data not shown). None of the protein levels were associated with PFS. Interestingly, pSTAT1 appeared to be associated with OS however, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.06).

Patient serum levels of two epidermal growth-factor receptor ligands, EGF and TGF-β were measured by ELISA at baseline and 8 weeks post-panitumumab-chemoradiation in 20 (45%) patients. There were no changes in serum levels of these cytokines from baseline to week 8.

discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the addition of the EGFR-targeting mAb panitumumab to the standard adjuvant cisplatin CRT in patients with high-risk, resected, HPV-negative HNSCC. Patients with these features on pathology were shown to benefit from the addition of cisplatin to adjuvant RT, as demonstrated by EORTC trial 22931 and RTOG trial 9501 [3, 4, 12]. Despite improved locoregional control and disease-free survival for patients with high-risk HNSCC treated with RT plus cisplatin compared with adjuvant RT alone, there remains a need for further therapy intensification given the high risk of recurrence, particularly in patients with HPV-negative disease. Targeting the EGFR pathway, such as with panitumumab, has been an area of interest for multimodal therapy given 80%–90% overexpression of this protein in HNSCC [6].

The primary endpoint of this phase II trial was PFS at 2 years, and this study was designed and powered to investigate whether 2-year PFS could be improved by the addition of panitumumab compared with historical controls. We specifically hypothesized that adding panitumumab would increase the 2-year probability of PFS to 70%, assuming that the control 2-year PFS for postoperative RT and cisplatin alone was 50% (the approximate 2-year PFS in RTOG 9501 was 55% at 2 year and 50% at 3 years) [4]. Forty-three patients were required to have sufficient power to detect this difference. Forty-six patients were accrued, 44 of whom were evaluable for response. The probability of PFS at 2 years was 70% (95% CI 58–85) and at 3 years PFS was 68% (90% CI = 57%–81%)/(95% CI = 55%–83%). The probability of 2-year OS, a secondary endpoint, was 72% (95% CI 60%–87%). The 3-year OS was 65% (90% CI = 54%–78%)/(95% CI = 52%–81%). Neither median PFS nor OS were reached for this trial.

Our results suggest that intensification of adjuvant therapy by the addition of panitumumab, a monoclonal antibody to EGFR, to the standard backbone of postoperative cisplatin CRT may be superior to CRT alone and promising for the treatment of high-risk, resected, HPV-negative HNSCC. The PFS rates reported compare favorably with RTOG 9501 and EORTC 22931 postoperative trials. When considering RTOG 9501 results, we assumed that 50% DFS would be a reasonable null hypothesis. While an assumption of 55% DFS could have been made, this would not have influenced the interpretation of our results. For instance, the protocol resulted in a 2 year PFS of 70% with a 95% CI of 58%–85%. Had we published the 90% confidence interval, which could actually be more appropriate for a small phase II trial, we could report a confidence interval of 60%–80%—the lower bound just touching 60%. Therefore, despite possibly underestimating the standard of care PFS, we can still claim the outcome was favorable when compared with the revised standard of care of 60% rather than 50%.

This regimen was found to be tolerable, with no treatment-related deaths reported. While about one-third (32%) of patients experienced treatment-related grade ≥3 toxicity, only five patients (11%) required a treatment delay, and only two patients (5%) were unable to complete radiation due to toxicities. The most common grade 4 toxicities were lymphopenia (18%) and mucositis (5%). The rates of grade 3–4 mucositis (41%) and grade 3–4 dysphagia (18%) was less than what reported by Mesia et al. (55% and 39%, respectively) with primary CRT and every-3-week panitumumab.

Gastrostomy tube placement for enteral nutrition was performed in a total of 27 patients (61%). Three patients (7%) required a feeding tube at 1 year. In contrast, a phase II trial of panitumumab added to primary CRT (unresected tumors), (CONCERT-1l (Mesia et al. [13]) failed to show benefit with panitumumab. Our smaller single-arm phase II study was conducted in the postoperative setting and it employed weekly cisplatin and weekly panitumumab (versus every-3-week cisplatin 75 mg/m2 and every-3-week panitumumab at 9 mg/kg for three doses used in CONCERT-1). It is uncertain whether these differences in the regimen account for the more promising efficacy results in this study. However, our regimen was better tolerated than the regimen used by Mesia et al. We acknowledge the biases that influence comparisons across historical controls, including patient selection and center experience.

Another trial failing to show a benefit with the addition of EGFR therapy was RTOG 0522, a randomized Phase III trial of definitive CRT with or without the addition of cetuximab [14]. Adding cetuximab to cisplatin and radiation in this trial did not show any different in 30-day mortality, 3-year PFS, 3-year OS, locoregional failure, or distant metastatic disease compared with the control arm. Both studies included HPV-positive patients who generally have better treatment outcomes, which may contribute to the negative results.

A possible reason for our positive results in the setting of numerous negative trials may lie in the differences between the EGFR inhibitors cetuximab and panitumumab. Panitumumab may be the better EGFR inhibitor in HPV-negative tumors, as suggested by the SPECTRUM trial, which added panitumumab to cisplatin and fluorouracil in recurrent/metastatic HNSCC and demonstrated a statistically significant benefit in OS for HPV-negative tumors compared with HPV-positive disease [15]. Other trials are also evaluating the intensification of multimodal therapy targeting the EGFR pathway, including RTOG 1216, a Phase III trial evaluating postoperative radiation delivered with concurrent cisplatin versus docetaxel versus docetaxel and cetuximab in patients with high-risk features of disease (NCT01810913).

Exploratory biomarkers were studied for correlation with inhibition of the EGFR pathway in addition to cisplatin therapy. Overexpression of the oncogene STAT3 in HNSCC has been well described [16]. STAT1, considered to be a tumor suppressor, has been activated by cisplatin in non-tumor cell lines [17, 18], and high STAT1 staining in tumor specimens has been suggested to be a good prognostic indicator in patients with HNSCC treated with platinum-based chemotherapy [19]. STAT1 activation is involved in adaptive immunity, and EGFR inhibition may enhance this immunity in an STAT1-dependent manner [20]. While cisplatin consistently activated STAT1 in HNSCC cell lines, the addition of EGFR inhibitors to cisplatin treatment caused variable effects among cell lines, with enhancement of cell death in some lines and minimal effect in others [21]. Based on these preclinical results, five STAT proteins were measured in tumor resection specimens from patients in this trial, including STAT1, STAT3, pSTAT3, pSTAT1Y, and pSTAT1S. Only half of the tumor specimens were available for analysis due to study enrollment after surgical resection from an outside institution. Despite promising preclinical data suggesting that STAT1 activation may be a useful biomarker in response to platinum-based therapy alone or in combination with EGFR inhibition, there were no differences in PFS or OS outcomes in this trial, possibly due to reduced power from a small sample.

In conclusion, intensification of adjuvant CRT with panitumumab demonstrated improved PFS and OS in this study among high-risk, resected, HPV-negative HNSCC patients, when compared with historical controls with standard treatment. This multimodal regimen was also found to be associated with acceptable and manageable toxicities. While selected biomarkers did not yield correlative results, it would be prudent for further study to identify patients who may benefit from combined platinum and EGFR-targeted therapies.

funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (grants R01 DE 019727, P50 CA097190, T32 CA060397) and used the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute award P30 CA047904.

disclosure

RLF: consulting or advisory role: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, ONO Pharmaceutical, and Celgene. Research funding: Amgen (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst.) AstraZeneca (Inst.), and VentiRx (Inst.). All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

references

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(14): 2137–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60(5): 277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(19): 1945–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(19): 1937–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goessel G, Quante M, Hahn WC et al. Creating oral squamous cancer cells: a cellular model of oral-esophageal carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102(43): 15599–15604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang KK, Berkey BA, Tu X et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor expression on survival and pattern of relapse in patients with advanced head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res 2002; 62(24): 7350–7356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin Grandis J, Melhem MF, Gooding WE et al. Levels of TGF-alpha and EGFR protein in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and patient survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90(11): 824–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(6): 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(11): 1116–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harari PM, Harris J, Kies MS et al. Postoperative chemoradiotherapy and cetuximab for high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group RTOG-0234. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(23): 2486–2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner LM, Belldegrun AS, Crawford J et al. Dose and schedule study of panitumumab monotherapy in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(2): 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernier J, Cooper JS, Pajak TF et al. Defining risk levels in locally advanced head and neck cancers: a comparative analysis of concurrent postoperative radiation plus chemotherapy trials of the EORTC (#22931) and RTOG (# 9501). Head Neck 2005; 27(10): 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mesía R, Henke M, Fortin A et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without panitumumab in patients with unresected, locally advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (CONCERT-1): a randomised, controlled, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang KK, Zhang Q, Rosenthal DI et al. Randomized phase III trial of concurrent accelerated radiation plus cisplatin with or without cetuximab for stage III to IV head and neck carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(27): 2940–2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermorken JB, Stöhlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(8): 697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leeman RJ, Lui VW, Grandis JR. STAT3 as a therapeutic target in head and neck cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2006; 6(3): 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt NC, Rubel EW, Nathanson NM. Cisplatin-induced hair cell death requires STAT1 and is attenuated by epigallocatechin gallate. J Neurosci 2009; 29(12): 3843–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Townsend PA, Scarabelli TM, Davidson SM et al. STAT-1 interacts with p53 to enhance DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(7): 5811–5820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laimer K, Spizzo G, Obrist P et al. STAT1 activation in squamous cell cancer of the oral cavity: a potential predictive marker of response to adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 2007; 110(2): 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srivastava RM, Trivedi S, Concha-Benavente F et al. STAT1-induced HLA class I upregulation enhances immunogenicity and clinical response to anti-EGFR mAb cetuximab therapy in HNC patients. Cancer Immunol Res 2015; 3(8): 936–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitt NC, Trivedi S, Ferris RL. STAT1 activation is enhanced by cisplatin and variably affected by EGFR inhibition in HNSCC cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2015; 14(9): 2103–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]