Abstract

Early afterdepolarization (EAD) plays an important role in arrhythmogenesis. Many experimental studies have reported that Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and β-adrenergic signaling pathway are two important regulators. In this study, we developed a modified computational model of human ventricular myocyte to investigate the combined role of CaMKII and β-adrenergic signaling pathway on the occurrence of EADs. Our simulation results showed that (1) CaMKII overexpression facilitates EADs through the prolongation of late sodium current's (I NaL) deactivation progress; (2) the combined effect of CaMKII overexpression and activation of β-adrenergic signaling pathway further increases the risk of EADs, where EADs could occur at shorter cycle length (2000 ms versus 4000 ms) and lower rapid delayed rectifier K+ current (I Kr) blockage (77% versus 85%). In summary, this study computationally demonstrated the combined role of CaMKII and β-adrenergic signaling pathway on the occurrence of EADs, which could be useful for searching for therapy strategies to treat EADs related arrhythmogenesis.

1. Introduction

Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) are triggered before the completion of repolarization [1] and associated with polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia for long QT syndrome patients [2]. Prolongation of action potential duration (APD) and recovery of L-type Ca2+ current have been reported as two important factors for the occurrence of EADs [3]. It is also known that the increase of inward currents (e.g., I CaL and late sodium current, I NaL) or the decrease of outward currents (e.g., rapid delayed rectifier K+ current, I Kr and slow delayed rectifier K+ current, I Ks) at plateau membrane voltage could increase the probability of EADs events. Therefore, any factors that could change the intensity or time sequence of these currents may lead to the occurrence of EADs [4–8].

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a key kinase in tuning cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Its substrates include ion channels, transporters, and accessory proteins [9]. It has been reported that CaMKII phosphorylates I CaL, leading to increased amplitude and APD prolongation and facilitating the occurrence of EADs [10, 11]. CaMKII can also alter I NaL, transient outward K current (I to), SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) [12], and ryanodine receptor (RyR) channels [10]. It would therefore be useful to understand and quantify these regulatory roles. However, it is very difficult for the laboratory experiments to achieve this. Computer modelling approaches provide alternative ways, allowing us to distinguish the most effective phosphorylation target of arrhythmogenesis, which would ultimately provide useful tool in searching for antiarrhythmia therapy.

It has been known that β-adrenergic signaling pathway regulates Ca2+ cycling partly via phosphorylation of I CaL and phospholamban (PLB) [13]. I CaL elevates intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca]i) and increases spontaneous Ca2+ release via the SERCA inhibition by PLB. The broken balance of Ca2+ cycling may contribute to the occurrence of EADs [14–16]. Volders et al. investigated the ionic mechanisms of β-adrenergic on the occurrence of EADs in canine ventricular myocyte and concluded that cellular Ca2+ overload and spontaneous SR Ca2+ release played important roles in EADs [17]. On the contrary, other studies reported that β-adrenergic agonists activate protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates I CaL, RyR, PLB, SERCA, and I Ks, resulting in delayed afterdepolarization (DADs) [18]. These numerous targets and different temporal characteristics of phosphorylation effects complicate the mechanism analysis of β-adrenergic agonists in relation to EADs. Recently, different computational models have been used to investigate these complex interactions. Xie et al. developed a biophysically detailed rabbit model and found that the faster time course of I CaL versus I Ks increased ISO-induced transient EADs [19] and emphasized the importance of understanding the nonsteady state of kinetics in meditating β-adrenergic-induced EADs and arrhythmia. However, other targets including I NaL have not been investigated thoroughly in their model. It is noted that, although the computational studies of EAD mechanisms have been widely taken, the majority of these published modelling studies have been developed based on nonhuman myocyte. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there is no modelling study considering the combined effect of CaMKII overexpression and β-adrenergic agonists on EADs.

This study aimed to develop a modified computational model of human ventricular myocyte that integrates CaMKII and β-adrenergic signaling networks into a modified ORd's dynamic model [20], with which the combined role of CaMKII and β-adrenergic signaling pathway on the occurrence of EADs would be investigated.

2. Methods

2.1. Integration of CaMKII

Since there is a lack of experimental measurements of human ventricle CaMKII pathway, O'Hara et al. used the Hund-Decker-Rudy's dog model to describe CaMKII kinetics [21, 22]. Our model was developed from the O'Hara-Rudy dynamic model (ORd model) to integrate CaMKII pathway [20]. The following equations describe the CaMKII kinetic of human ventricle:

| (1) |

The fraction of active CaMKII binding sites at equilibrium state (CaMK0) was set to 0.05 at the control state. CaMK0 of 0.12 was used to simulate CaMKII overexpression according to the study from Kohlhaas et al. [23].

2.2. Integration of β-Adrenergic Signaling Networks

The detailed description of β-adrenergic signaling networks could be found from the published study by Soltis and Saucerman [24]. PKA has been reported to phosphorylate I CaL, PLB, troponin I, RyR, myosin binding protein-C, protein phosphates Inhibitor-I [25], and I Ks [24]. I CaL, PLB, and I Ks were the three key factors in this study to model the inotropic effect of β-adrenergic related to potential EADs occurrence. Although the PKA phosphorylation of Na+/K+ ATPase current (I NaK) has been previously described in the computational models [19, 26], its effect was not included in this study partially because there is a lack of direct measurements of I NaK for the normal human ventricle [20]. The phosphorylation by PKA to the three targets (I CaL, PLB, and I Ks) is described as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Equation (2) shows the coefficient that represents the effect of PKA on I CaL phosphorylation. In (3), the value of “vshift” was increased from 3.94 (no ISO application) to 10.0 (for saturated ISO application), which means that the steady state activation curve of I CaL was moved left by 6.06 mV. The permeability of ion Ca2+ was increased by 10% with saturated ISO application. Equation (4) describes the augmentation of I CaL amplitude by multiplying “f avail” with the value without PKA phosphorylation, and this represents how PKA regulates I CaL. In (6), the time constant of activation gate (td) was extended by 20% with saturated ISO application

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Equation (7) describes the factor of phosphorylation to I Ks by PKA, which was used to alter maximum conductance of I Ks (GKs) in (8). Meanwhile, I Ks state steady activation curve was adjusted by time dependent gate value through the factor “fracI Ksavail” in (9) and (10).

2.3. Combination of CaMKII and β-Adrenergic Signaling Networks

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

CaMKactive that is affected by CaMK0 as shown in (1) would influence I CaL in (4) via the fraction of I CaL channels phosphorylated by CaMKII (ΦICaL,CaMK). The fraction of SERCAs phosphorylated by CaMKII in (12) was affected by “fPKAPLB” and “CaMKactive”, representing the effects of PKA and CaMKII on SERCAs, respectively. As shown in (13), SERCAs were separated into nonphosphorylated populations and CaMKII phosphorylated populations. Therefore, the total Ca2+ uptake via SERCAs was adjusted by these two networks simultaneously.

2.4. Simulation Strategy

In order to determine the potential targets in CaMKII-induced EADs, CaMKII was solely overexpressed by assigning the CaMK0 of 0.12 to specific targets (including I NaL, I CaL, I CaK, I NaCa, and I to), respectively, while β-adrenergic signaling was maintained inactive. Next, CaMKII overexpression was applied with ISO administration. 1 μM ISO was applied in this study to simulate its effect on myocyte action potential and ion currents.

The cycle length of 2000 ms was used in this study since it was closer to normal human beat rhythm than the length of 4000 ms used in the experiments from Guo et al. [27]. In Guo et al.'s work, EADs appeared with I Kr blockage of about 85% [27], which was used for comparison in this study. 500 cycles were performed when the simulation reached steady state. In each individual cycle length, the upper bound of solver step size was set 2 ms.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of CaMKII Overexpression on Ion Currents

3.1.1. Late Sodium Current (I NaL)

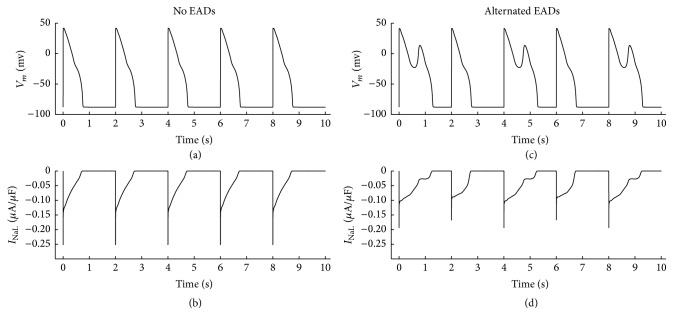

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, with the overexpressed CaMK0 value to I NaL of 0.12 and the normal CaMK0 value of 0.05 to other targets, the alternated EADs occur from our simulation with the cycle length (CL) of 2000 ms and I Kr blockage of 85%.

Table 1.

Current increment and EADs occurrence when different targets were phosphorylated by CaMKII independently.

| Cycle length (ms) | I Kr blockage level (%) | CaMKII target (CaMK0 = 0.12) | Target current variation | Deactivation time (ms) | EADs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 85 | I NaL | Decreased by 24% (from 0.25 to 0.19 µA/µF) |

1297 versus 761 ms | Alternated |

| I CaL | Increased by 4.2% (from 1.67 to 1.74 µA/µF) |

No | |||

| I CaK | Increased by 6.5% (from 0.62 to 0.66 µA/µF) |

No | |||

| I CaNa | Increased by 8.1% (from 0.37 to 0.40 µA/µF) |

No | |||

| I to | Increased by 3.2% (from 0.95 to 0.98 µA/µF) |

No |

Figure 1.

(a) No EAD was produced when CaMKII phosphorylation level was in control (CaMK0 = 0.05). (b) Corresponding I NaL when no EADs occurred in (a). (c) Alternated EADs were produced when I NaL phosphorylation by CaMKII was enhanced with CaMK0 of 0.12 and other targets' phosphorylation levels were in control (CaMK0 = 0.05). (d) Corresponding I NaL when alternated EADs occurred in (c). Under these conditions, CL was 2000 ms and I Kr was blocked by 85%.

As shown in Figure 1, INaL amplitudes alternated with overexpressed CaMK0. In beats with EADs, I NaL amplitude was about 24% smaller (0.19 μA/μF versus 0.25 μA/μF) than these with normal CaMK0 value to I NaL and in beats without EADs, I NaL amplitude was also reduced by 32% (0.17 μA/μF versus 0.25 μA/μF). In Figure 1(d), when EADs occurred, I NaL deactivated, which was about 168% of normal beats (1297 ms versus 773 ms) and about 170% of the control situation in Figure 1(b) (1297 ms versus 761 ms), indicating that overexpressed CaMKII phosphorylation level of I NaL reduces its amplitude and prolongs I NaL deactivation process. Furthermore, the results also indicate that the delayed deactivation of I NaL, rather than its amplitude variation, contributes to the formation of EADs.

3.1.2. L-Type Calcium Current (I CaL)

Similarly, as shown in Table 1, with the overexpressed CaMK0 to I CaL of 0.12 and the normal CaMK0 value of 0.05 to other targets, no EADs occur at CL of 2000 ms and I Kr blockage of 85%, suggesting that the probability of EADs might have little relation with amplitude of I CaL. With the enhanced CaMK0 value to I CaL, the amplitudes of I CaL only increased by 4.2% (1.74 μA/μF versus 1.67 μA/μF).

3.1.3. K+ Current through the L-Type Ca2+ Channel (I CaK), Na+ Current through the L-Type Ca2+ Channel (I CaNa), and Transient Outward K+ Current (I to)

As above, CL was set to 2000 ms and I Kr was blocked by 85%. As shown in Table 1, with enhanced CaMKII phosphorylation level (CaMK0 = 0.12) to different targets, I CaK increased only by 6.5% (0.66 μA/μF versus 0.62 μA/μF), I CaNa by 8.1% (0.40 μA/μF versus 0.37 μA/μF), and I to by 3.2% (0.98 μA/μF versus 0.95 μA/μF). No EADs occurred under all these conditions.

3.2. Combined Effect of CaMKII Overexpression and β-Adrenergic Agonist

3.2.1. Normal CaMKII and 1 μM ISO

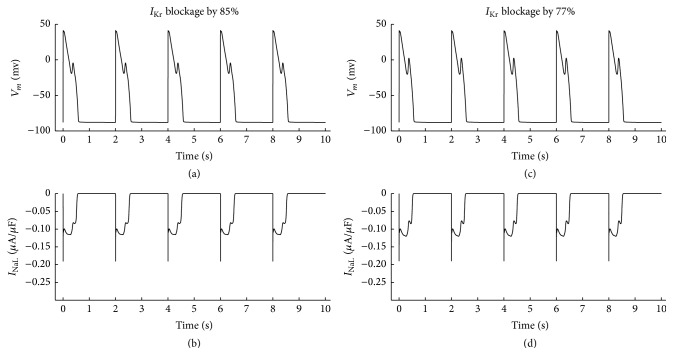

The action potentials with different I Kr blockage level are shown in Figure 2. A fixed CL =2000 ms was used and CaMKII phosphorylation level to all targets was kept control (CaMK0 = 0.05). In Figure 2(a), with I Kr blocked by 85%, stable EADs occurred with the application of ISO, indicating that β-adrenergic agonist facilitates EADs. The I Kr blockage level decreased gradually from 85%, and, when it was decreased to 77%, as shown in Figure 2(b), these EADs disappeared, indicating that 77% was the threshold value for EADs disappearance in this setting. Therefore, 77% was used in following simulation to compare with previously published level of 85% [20]. These results are listed from row 2 to row 3 in Table 2.

Figure 2.

(a) EADs were induced when 1 μM ISO was applied and I Kr was blocked by 85%. In (b), EADs disappeared when I Kr blockage was reduced to 77%. Cycle length was set 2000 ms and CaMKII phosphorylation level to all targets was kept control (CaMK0 = 0.05).

Table 2.

Combined effect of CaMKII overexpression and β-adrenergic agonist on EADs.

| Cycle length (ms) | ISO application | CaMKII target (CaMK0 = 0.12) | I Kr blockage level (%) | EADs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | None | None | 85 | None |

| 1 µM | None | 85 | Yes | |

| None | 77 | No | ||

| I NaL | 85 | Yes | ||

| I NaL | 77 | Yes | ||

| I CaL | 85 | Yes | ||

| I CaL | 77 | No |

3.2.2. Enhanced CaMKII to I NaL and 1 μM ISO

As shown in Figure 3, with enhanced CaMKII to I NaL and 1 μM ISO, when I Kr was blocked by 85%, EADs were induced. The EADs were still observed when I Kr was blocked by 77%, suggesting that I NaL phosphorylation by CaMKII and ISO application together increased the probability of EADs. These results are listed from row 4 to row 5 in Table 2.

Figure 3.

EADs occurred when I Kr was blocked by 85% (a) and 77% (c); corresponding I NaL when I Kr was blocked by 85% (b) and 77% (d). CL was set 2000 ms, 1 μM ISO was applied and CaMK0 for I NaL was set 0.12 independently.

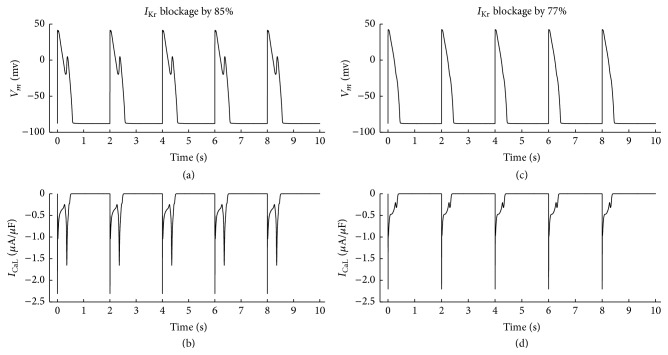

3.2.3. Enhanced CaMKII to I CaL and 1 μM ISO

As shown in Figure 4, with enhanced CaMKII to I CaL and 1 μM ISO, when I Kr was blocked by 85%, EADs were induced, but when I Kr blockage was reduced to 77%, EADs disappeared. These results are listed from row 6 to row 7 in Table 2.

Figure 4.

1 μM ISO was applied and cycle length was 2000 ms. CaMK0 for I CaL was 0.12 but CaMK0 for other targets was 0.05. EADs occurred when I Kr was blocked by 85% in (a), but when I Kr blockage was reduced to 77%, EADs vanished in (c). (b) I CaL figures when EADs existed. (d) I CaL figures when EADs vanished.

4. Discussion

This study developed a modified computational model of human ventricular myocardium cell based on the ORd human model with the integration of regulation mechanism by CaMKII and PKA [20], with which their effects on EADs have been investigated.

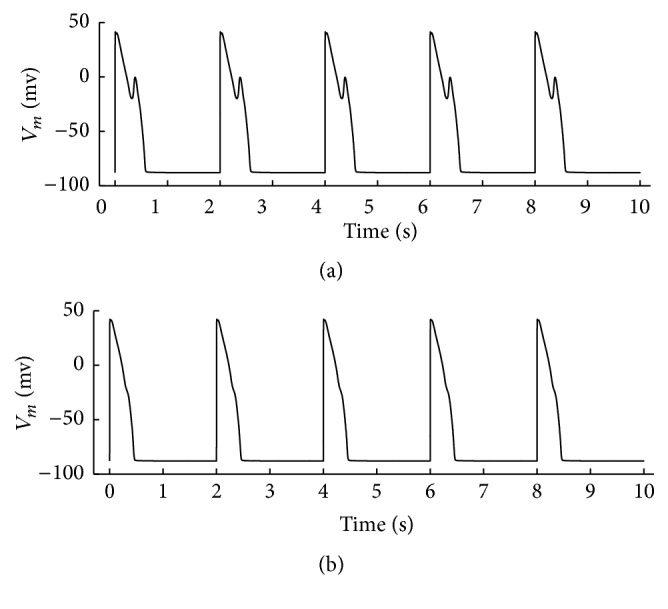

EADs often occur during bradycardia under the condition of reduced repolarization reserve. O'Hara's group successfully elicited EADs with cycle length reduced to 4000 ms and I Kr blocked by 85% [20]. In our simulation, with the cycle length halved (2000 ms) and I Kr blocked by 85%, alternated EADs occurred with the sole effect of CaMKII overexpression to I NaL, suggesting that ventricular myocardial cell with CaMKII overexpression is more susceptible to EADs in normal HR range (CL = 2000 ms). Additionally, previous work has shown that I CaL plays an important role in the occurrence of EADs [6]. Our simulation showed that CaMKII overexpression slightly increased I CaL amplitude, but this effect alone did not induce EADs, and CaMKII did not alter the overlap region of I CaL steady state activation and reactivation curves. Zaza et al. reported that [28], when repolarization is suitably slow, channel reactivation within the overlap region may break the current balance and support the possibility of autoregenerative depolarization. Other inward currents such as Na+-Ca2+ exchange current (I NaCa) may play certain roles in triggering EADs if amplitude is augmented and falls into the overlap region. Our simulation results suggest that CaMKII enhances these currents but does not induce EADs via this effect individually. Therefore, when CaMKII is overexpressed, the susceptibility to EADs is mainly originated from I NaL variation.

Our study also demonstrated the behavior of ventricular myocardial cell with the integration of CaMKII overexpression and ISO application. With the ISO application, cyclic AMP (cAMP) is formed through β-adrenergic mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase, which activates PKA, a well-described mediator with targets that promote myocardial performance. In the case where PKA took effect independently, EADs occurred with shorter cycle length (2000 ms versus 4000 ms), indicating that the precondition of EADs is relaxed. Our results were different from that from Xie et al.'s study, where the APD shortening after ISO application was observed without EADs in steady state [19]. Xie et al.'s results could be caused by the simulation of transient I CaL recovery and the prevented spontaneous SR Ca2+ release, limiting the I NaCa in forward mode. Therefore, when the cells step into steady state with small inward I NaCa, the shortening of APD could be reasonable. In our work, SR Ca2+ release was enhanced by I CaL amplification. With the integration with I Kr blockage, I NaCa was more likely to work as inward current, contributing to the prolongation of APD and occurrence of EADs. Additionally, the shortening of APD was also obtained without I Kr blockage when β-adrenergic pathway was activated. Simulation results showed that when cycle length was chosen at 500 ms, 1000 ms, 1500 ms, 2000 ms, and 4000 ms, the corresponding APD90 shortening was 31.6 ms (233.0 versus 201.4 ms), 30.5 ms (268.6 versus 238.1 ms), 22.3 ms (282.6 versus 260.3 ms), 17.3 ms (289.1 versus 271.8 ms), and 18.6 ms (305.6 versus 287.0 ms). These results were consistent with the experiment measurements from Volders et al. [29]. In the case that CaMKII overexpression acted on I NaL alone with ISO application, EADs occur at CL = 2000 ms and I Kr blockage by 77%, suggesting that the combination of PKA and CaMKII overexpression on I NaL relaxes the precondition further (I Kr blockage 77% versus 85%) and increases the probability of EADs. With the CaMKII overexpressed on I CaL alone, PKA induced EADs occurrence with 85% I Kr blockage, not 77% I Kr blockage, suggesting that, with the ISO application, I NaL phosphorylation by CaMKII has more effect on EADs than I CaL. The steady state of CaMKactive was simulated with and without ISO application when CL = 2000 ms, and their corresponding maximum values were 0.0469 and 0.0421, respectively. This suggests that CaMKII activation increased with the application of ISO.

Our simulation results have shown that our proposed model is useful for exploring the interaction of β-adrenergic receptor signaling and CaMKII in formation of EADs; some potential limitations need to be addressed. Firstly, the role of CaMKII on RyR function has not been considered. There is growing evidence about its role in modulating RyR function. Increasing Ca2+ leak via RyR would limit SR Ca2+ load and disturb Ca2+ cycling. This should be incorporated into an improved model in a future study. Secondly, CaMKII overexpression may downregulate inward rectifier potassium current (I K1) and increase baseline I K1 amplitude [30]. We did not include any CaMKII effect on I K1 in our model. Thirdly, our model only describes the short-term effect of CaMKII on different current targets. It has been suggested that short-term and chronic effects of CaMKII are different [30–33]. Short-term (milliseconds to hours) CaMKII overexpression may slow I to inactivation and accelerate recovery, but chronic overexpression may downregulate I to,fast and upregulate I to,slow [34]. Therefore, there is a scope to improve our model by taking chronic effects of CaMKII into consideration in future. Fourthly, there is a lack of an accurate measurement about how ISO regulates I NaK with dynamic calcium change during the beat cycle, although it has been published by Gao et al. [35] that ISO regulated INaK increased (when calcium is 1.4 μM) or decreased in pump current (when calcium is 0.15 μM) depending on the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. In our model the resting calcium concentration was 0.12 μM and the peak calcium concentration was 1.1 μM. Similar to the simulation work of Heijman et al. [26], by simply increasing the pump current from 17% to 33%, no significant change of I NaK in triggering EADs (results not shown here) has been observed. However, when the continuous experimental data from human ventricular cells is available, the regulation of ISO on I NaK could be incorporated into the model to reconfirm this nonsignificant effect. Fifthly, it has been reported that local regulation of cAMP and substrate phosphorylation play important roles in β-adrenergic receptor signaling [26, 36–38], so it could be useful to incorporate local control mechanism in a future study. Lastly, there are four CaMKII isoforms (α, β, γ, δ) with different distributions, kinetics, and roles in physiological and pathological adjustments. Until now, these differences have not been fully understood. Developing a model with detailed CaMKII isoforms information could be useful when experiment data are available.

In conclusion, our simulation results computationally demonstrated a better understanding of the combinational effect of CaMKII and ISO stimulus on the occurrence of EADs in human ventricular myocyte, which may provide useful tool to research therapeutic methods for the treatment of arrhythmia.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61527811).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Cranefield P. F., Aronson R. S. Cardiac Arrhythmias: The Role of Triggered Activity and Other Mechanisms. New York, NY, USA: Futura Publishing Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss J. N., Garfinkel A., Karagueuzian H. S., Chen P.-S., Qu Z. Early afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(12):1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng J., Rudy Y. Early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes: mechanism and rate dependence. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68(3):949–964. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(95)80271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antzelevitch C., Sun Z.-Q., Zhang Z.-Q., Yan G.-X. Cellular and ionic mechanisms underling erythromycin-induced long QT intervals and Torsade de Pointes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;28(7):1836–1848. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu W., Antzelevitch C. Sodium channel block with mexiletine is effective in reducing dispersion of repolarization and preventing torsade de pointes in LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1997;96(6):2038–2047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.January C. T., Riddle J. M., Salata J. J. A model for early afterdepolarizations: Induction with the Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644. Circulation Research. 1988;62(3):563–571. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.January C. T., Riddle J. M. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circulation Research. 1989;64(5):977–990. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhvani R. V., Xie Y., Pantazis A., et al. Shaping a new Ca2+ conductance to suppress early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of Physiology. 2011;589(24):6081–6092. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohler P. J., Hund T. J. Role of CaMKII in cardiovascular health, disease, and arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(1):142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y., Temple J., Zhang R., et al. Calmodulin kinase II and arrhythmias in a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2002;106(10):1288–1293. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000027583.73268.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashambhoy Y. L., Greenstein J. L., Winslow R. L. Role of CaMKII in RyR leak, EC coupling and action potential duration: a computational model. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2010;49(4):617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swaminathan P. D., Purohit A., Hund T. J., Anderson M. E. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: linking heart failure and arrhythmias. Circulation Research. 2012;110(12):1661–1677. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.111.243956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bers D. M. Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. 2nd. Boston, Mass, USA: Kluwer/Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verduyn S. C., Vos M. A., Gorgels A. P., Van der Zande J., Leunissen J. D. M., Wellens H. J. The effect of flunarizine and ryanodine on acquired torsades de pointes arrhythmias in the intact canine heart. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 1995;6(3):189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlsson L., Drews L., Duker G. Rhythm anomalies related to delayed repolarization in vivo: Influence of sarcolemmal Ca2+ entry and intracellular Ca2+ overload. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1996;279(1):231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song Z., Ko C. Y., Nivala M., Weiss J. N., Qu Z. Complex darly and delayed afterdepolarization dynamics caused by voltage-calcium coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2015;108(8):261A–262A. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volders P. G. A., Kulcsár A., Vos M. A., et al. Similarities between early and delayed afterdepolarizations induced by isoproterenol in canine ventricular myocytes. Cardiovascular Research. 1997;34(2):348–359. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(96)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.January C. T., Fozzard H. A. Delayed afterdepolarizations in heart muscle: mechanisms and relevance. Pharmacological Reviews. 1988;40(3):219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie Y., Grandi E., Puglisi J. L., Sato D., Bers D. M. β-Adrenergic stimulation activates early afterdepolarizations transiently via kinetic mismatch of PKA targets. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2013;58(1):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Hara T., Virág L., Varró A., Rudy Y. Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: model formulation and experimental validation. PLoS Computational Biology. 2011;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002061.e1002061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decker K. F., Heijman J., Silva J. R., Hund T. J., Rudy Y. Properties and ionic mechanisms of action potential adaptation, restitution, and accommodation in canine epicardium. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009;296(4):H1017–H1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01216.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hund T. J., Rudy Y. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation. 2004;110(20):3168–3174. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147231.69595.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohlhaas M., Zhang T., Seidler T., et al. Increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak but unaltered contractility by acute CaMKII overexpression in isolated rabbit cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 2006;98(2):235–244. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200739.90811.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soltis A. R., Saucerman J. J. Synergy between CaMKII substrates and β-adrenergic signaling in regulation of cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling. Biophysical Journal. 2010;99(7):2038–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohse M. J., Engelhardt S., Eschenhagen T. What is the role of β-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circulation Research. 2003;93(10):896–906. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000102042.83024.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heijman J., Volders P. G. A., Westra R. L., Rudy Y. Local control of β-adrenergic stimulation: effects on ventricular myocyte electrophysiology and Ca2+-transient. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;50(5):863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo D., Liu Q., Liu T., et al. Electrophysiological properties of HBI-3000: a new antiarrhythmic agent with multiple-channel blocking properties in human ventricular myocytes. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2011;57(1):79–85. doi: 10.1097/fjc.0b013e3181ffe8b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaza A., Belardinelli L., Shryock J. C. Pathophysiology and pharmacology of the cardiac ‘late sodium current’. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2008;119(3):326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volders P. G. A., Stengl M., Van Opstal J. M., et al. Probing the contribution of IKs to canine ventricular repolarization: key role for β-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Circulation. 2003;107(21):2753–2760. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000068344.54010.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner S., Hacker E., Grandi E., et al. Ca/calmodulin kinase II differentially modulates potassium currents. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2009;2(3):285–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.842799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessier S., Karczewski P., Krause E.-G., et al. Regulation of the transient outward K+ current by Ca2+/calmodulin- dependent protein kinases II in human atrial myocytes. Circulation Research. 1999;85(9):810–819. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colinas O., Gallego M., Setién R., López-López J. R., Pérez-García M. T., Casis O. Differential modulation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channels by calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in rat cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;291(4):H1978–H1987. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01373.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sergeant G. P., Ohya S., Reihill J. A., et al. Regulation of Kv4.3 currents by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2005;288(2):C304–C313. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00293.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson M. E., Brown J. H., Bers D. M. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;51(4):468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao J., Wymore R., Wymore R. T., et al. Isoform-specific regulation of the sodium pump by α- and β-adrenergic agonists in the guinea-pig ventricle. The Journal of Physiology. 1999;516(2):377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0377v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolaev V. O., Moshkov A., Lyon A. R., et al. β 2-Adrenergic receptor redistribution in heart failure changes cAMP compartmentation. Science. 2010;327(5973):1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1185988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright P. T., Nikolaev V. O., O'Hara T., et al. Caveolin-3 regulates compartmentation of cardiomyocyte beta2-adrenergic receptor-mediated cAMP signaling. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;67:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iancu R. V., Jones S. W., Harvey R. D. Compartmentation of cAMP signaling in cardiac myocytes: a computational study. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92(9):3317–3331. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]