Abstract

This study examined whether mindfulness strategies (e.g., acting non-judgmentally with awareness and attention to present events) were effective in mitigating the associations among school-based victimization related to ethnicity and sexual orientation, well-being (i.e., depressive symptoms and self-esteem), and grade-point average (GPA). The U.S.-based sample included 236 Latina/o sexual minority students, ranging in age from 14 to 24 years (47% were enrolled in secondary schools, 53% in postsecondary schools). Results from structural equation modeling revealed that ethnicity-based school victimization was negatively associated with GPA but not well-being. However, sexual orientation-based victimization was not associated with well-being or GPA. Mindfulness was positively associated with well-being but not GPA. High levels of mindfulness coping were protective when the stressor was sexual orientation-based victimization but not ethnicity-based school victimization. These findings contribute to a growing literature documenting the unique school barriers experienced by Latina/o sexual minority youth and highlight the promising utility of mindfulness-based intervention strategies for coping with minority stress.

Keywords: Bias-based victimization, ethnicity, mindfulness, sexual orientation, youth

Several studies have documented the unique minority-related stressors (e.g., bias-based victimization) that sexual minority adolescents encounter at school (Toomey & Russell, 2016), as well as the robust associations among these risk factors and poor health and academic outcomes (Collier, van Beusekom, Bos, & Sandfort, 2013; Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card, & Russell, 2010). Similarly, others have documented the unique stressors that youth of color experience at school (e.g., racial/ethnic-based victimization, Lai & Tov, 2004; Robers, Kemp, Rathbun, Morgan, & Snyder, 2014; Russell et al., 2012), and that these risk factors are also associated with poor health and academic outcomes (Pachter & Coll, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). However, few studies have examined how the multiple biased-based school experiences of sexual minority youth of color simultaneously contribute to disparate health or academic outcomes, and even fewer have identified protective factors for sexual minority youth of color (Institutes of Medicine [IOM], 2011). Information about protective factors for multiply marginalized populations is critical for developing successful interventions designed to disrupt the negative associations between minority stress and poor health and academic outcomes.

Framed by Meyer’s (2003) minority stress perspective and a risk and resilience framework (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000), this study examined whether mindfulness strategies mitigate the robust negative associations between encountered bias at school and psychosocial (i.e., depressive symptoms, self-esteem) and academic (i.e., grade-point average [GPA]) functioning in a sample of Latina/o sexual minority youth. Mindfulness strategies, in particular, may protect marginalized youth from encountered bias, given that these strategies help people to accept themselves and not ruminate on problems that may be beyond their immediate control, such as minority stress (Mendelson et al., 2010). A focus on the experiences of Latina/o youth is warranted given that Latinos represent one of the fastest growing populations in the U.S. (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, & Albert, 2011). Importantly, the majority of Latinos in the U.S. are of Mexican descent and are, on average, a younger population compared to other racial-ethnic groups in the U.S. (Stepler & Brown, 2015).

Risk and Resilience: Minority Stress and Coping

As described by Meyer (2003), minority stress includes stress that results from individuals’ social positioning in marginalized groups (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, sexual minorities). Accordingly, minority stressors are posited to have a unique explanatory relationship with poor health and academic outcomes, above and beyond the daily stressors that people encounter (Meyer, 2003). Several studies document the pervasiveness of minority stress among Latina/o and sexual minority youth, albeit separately. Sexual minority youth experience pervasive minority stress related to their sexual orientation and gender expression (e.g., IOM, 2011; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Toomey & Russell, 2016). Several studies have found that minority stressors related to sexual orientation contribute to lower self-esteem, higher depressive symptomatology, and lower academic achievement (e.g., Russell et al., 2012; Toomey et al., 2010). Latina/o youth also encounter pervasive forms of ethnic-racial minority stress at school and in their communities (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003). Minority stress among Latina/o youth is associated with lower self-esteem, higher depressive symptomatology, and lower academic achievement (e.g., Behnke, Plunkett, Sands, & Bámaca-Colbert, 2011; Delgado, Updegraff, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011; Edwards & Romero, 2008; Roche & Kuperminc, 2012; Stein, Gonzalez, & Huq, 2012).

Both the minority stress framework (Meyer, 2003) and a risk and resilience framework (Luthar et al., 2000) suggest that the association between minority stressors and poor well-being and academic outcomes may be mitigated by efficacious coping. Coping has been defined as “cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). Several hierarchies of adolescent coping exist (e.g., Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996; Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007), and research suggests that how adolescents cope with stressors (i.e., which coping strategy or combination of strategies youth use) has implications for their well-being (e.g., Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007).

According to Compas and colleagues (2001), coping strategies can be categorized by whether they are directed at the stressor (e.g., engagement or approach coping) or directed at avoiding the stressor (e.g., disengagement or avoidance coping). Across the adolescent development literature, avoidance coping strategies are associated with increased internalizing and externalizing problems (Compas et al., 2001). Comparatively, approach-oriented coping strategies are often conceptualized as positive mechanisms to deal with stress (e.g., Compass et al., 2001). Thus, framed by the extant literature, avoidant strategies are often conceptualized as maladaptive whereas approach or engagement strategies are often conceptualized as adaptive.

Coping with Minority Stress

In studies focused on resilience among sexual minority youth, the emphasis has often been placed on the systems surrounding the young person, rather than the coping strategies of sexual minority youth. That is, the extant literature focused on how sexual minority youth cope with minority stress has largely focused on how school policies and practices or involvement in support groups may buffer the experiences of school victimization related to sexual orientation or gender identity and expression (see Russell & Fish, 2016). The exceptions to this focus in the literature include studies that attend to sexual minority youths’ availability of social support in their interpersonal networks (e.g., D’Augelli, 2003; Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010; Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010; Sheets & Mohr, 2009; Shilo & Savaya, 2011; Snapp, Watson, Russell, Diaz, & Ryan, 2015). According to these studies, support from peers and parents has been shown to be positively associated with self-esteem and negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Very few studies have examined how sexual minority youth cope with minority stress at the individual level. Research on sexual minority adults suggests that individuals may use more maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., disengagement, avoidance) – compared to adaptive strategies – when responding to minority stress (e.g., Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2009). Importantly, in both of these latter studies, maladaptive coping (e.g., coping strategies that are suppressive or reactive) mediated the link between minority stress and psychological distress, suggesting that minority stress contributes to distress partially through the use of these coping strategies. Further, additional studies of sexual minority adults have found that maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., disengagement, self-blame) were associated with poor mental health outcomes (Lehavot, 2012).

Lock and Steiner (1999) studied individual-level coping in response to general stress, rather than minority stress, and found that sexual minority youth reported higher use of approach and avoidant coping styles relative to their heterosexual counterparts. Among adults, gay and bisexual men also used avoidance strategies more often than heterosexual men (Sandfort, Bakker, Schellevis, & Vanwesenbeeck, 2009). Kuper, Coleman, and Mustanski (2014) examined coping strategies used by sexual minority youth of color. They found that the majority of youth used avoidance strategies (e.g., ignore or not be affected by other’s views or reactions) to deal with minority stress related to their sexual orientation. In their study, youth also discussed the use of avoidance and approach coping strategies to deal with minority stress due to their race or ethnicity (e.g., avoidance of conflicts, promotion of individuality). The efficacy of these approaches, however, was not considered. A very recent study by Goldbach and Gibbs (2015) examined how sexual minority youth cope with minority stress; consistent with the findings by Kuper and colleagues (2014), youth in the Goldbach and Gibbs (2015) study commonly endorsed avoidant coping strategies.

Similarly, few studies have examined how Latina/o youth cope with minority stress. Much of the growing literature on how Latina/o youth cope with minority stress has focused on maladaptive coping responses, such as substance use or problem behaviors, which can also be conceptualized as avoidance strategies. For example, several studies have documented, for example, that racial/ethnic discrimination is related to poor health and problem behaviors among youth (for review, see Pascoe & Richman, 2009). Further, some studies have found that racial/ethnic discrimination among Latina/o college students contributed to increased alcohol use problems (Cheng & Mallinckrodt, 2015). These findings suggest that minority stress may lead to maladaptive coping responses, such as alcohol or substance use.

Work focused on approach coping strategies among Latinos has been mixed. Some studies have found that approach coping styles were effective in reducing the contribution of discrimination on self-esteem among Latina/o young adolescents (Edwards & Romero, 2008). Additional research has found a bidirectional relationship between approach coping with discrimination and higher self-esteem (Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). Other research, however, has found that the association between discrimination and internalizing symptoms was only buffered by disengagement coping (Brittian, Toomey, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2013). Thus, it is unclear from the literature how to best support youth who encounter minority stress related to their ethnicity or race. Further, given that only the Kuper and colleagues (2014) study, discussed above, has examined coping among sexual minority youth of color, more research is clearly needed to understand how youth cope with multiple minority stressors.

Mindfulness as a Coping Strategy

Mindfulness strategies are rooted in Buddhist traditions of consciousness, attention, and awareness, and involve attending to the present moment in a non-judgmental way (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Mindfulness, as it is traditionally conceptualized, helps to build youths’ capacity to manage reactions to stressful events as they naturally occur in non-judgmental ways and without attempts to control these events (e.g., Baer, 2003; Hargus, Crane, Barnhofer, & Williams, 2010). A growing number of studies suggest that mindfulness-based interventions may reduce internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents (e.g., Biegel, Brown, Shaprio, & Schubert, 2009; Bögels, Hoogstad, van dun, De Schutter, & Restifo, 2008; Lee, Semple, Rosa, & Miller, 2008; Zylowska et al., 2008). Further, a pilot study documented promising effects of a mindfulness-based intervention for urban youth showing that intervention reduced problematic coping reactions to stress (e.g., rumination; Mendelson et al., 2010). A second study (Edwards, Adams, Waldo, Hadfield, & Beigel, 2014) also found that mindfulness-based interventions were effective in increasing mindfulness attention and awareness and reducing levels of stress among Latina/o youth. Finally, a third study (Le & Proulx, 2015) found that a mindfulness-based intervention attenuated stress for Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander youth.

Mindfulness, although underexplored as a coping mechanism related to minority stress, may be effective in buffering negative experiences for sexual minority youth – particularly youth from multiple marginalized backgrounds. This is particularly true given research that suggests that sexual minority adults may experience feelings of inferiority or shame as a result of encountered minority stress (Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014). Although focused on adult gay men, one study found that mindfulness was related to less use of avoidance coping and improved mental health for sexual minorities (Gayner et al., 2012). Other research with heterosexual adults has shown that mindfulness is positively associated with a greater ability to separate stressful events from individuals’ sense of self-worth (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). Still, we are not aware of any studies examining whether mindfulness is protective against minority stress among sexual minority adolescents. When engaged in mindful practice, a young person who encounters minority stress may respond more objectively to their feelings (“I am aware that I am upset because I am encountering discrimination.”) rather than in a shameful or judgmental way (e.g., “I’m being discriminated against. Something must be wrong with me.” or “I am upset as a result of this encounter – I am just an angry person”).

Current Study

Given the strong and consistent associations between minority stress, well-being, and academic achievement, we sought to understand whether mindfulness buffered the association between bias-based victimization related to sexual orientation and ethnicity and depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and grade-point average among Latina/o sexual minority youth. We hypothesized that high levels of mindfulness would buffer the association between minority stress (bias-based victimization related to both sexual orientation and ethnicity) and well-being and academic achievement among Latina/o sexual minority youth.

Method

Procedure

The analytic sample for this study was drawn from a larger project focused on the family, school, and identity experiences of Latina/o sexual minority youth. Participation in the study required that youth: (1) be between the ages of 14 and 24 years; (2) identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, or with another non-heterosexual sexual identity, or a non-cisgender gender identity (note: all trans-identified youth in the current sample also identified as sexual minorities); (3) identify as Latina/o; and (4) live in the U.S. or a U.S. territory (including military bases).

The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) posted the recruitment messages on its main social media pages (i.e., Facebook and Twitter), as well as to targeted GLSEN chapter social media outlets (i.e., chapters in localities with high proportions of Latina/o residents – Arizona, California, Florida, New York, Nevada, and Texas). Recruitment messages were also posted by the authors to their Facebook and Twitter pages. Recruitment spanned from late October 2014 to early November 2014, and messages were posted in both Spanish and English. Participants were compensated with a $10 Amazon.com electronic gift card for completing the survey. The procedure was approved by the institution’s human subjects review board and GLSEN’s Research Ethics Review Committee. Parental waiver of consent was granted in order to prevent unnecessary disclosure of minor participant’s sexual orientation to their parents (Mustanski, 2011).

Sample

The analytic sample for the current study included 236 Latina/o sexual minority youth who were currently enrolled in school. Of note, the original sample consisted of 385 Latina/o sexual minority youth: only 236 youth who were enrolled in school at the time of the study were selected for the current study given the focus on school-based minority stress. Participants ranged in age from 14 to 24 years (Mean = 19, SD = 2.30). Approximately 47% were enrolled in secondary schooling, with the remainder enrolled in post-secondary education. Most participants lived in urban environments (68.6%), and were geographically diverse (19% East; 17% Midwest; 24.2% South; 16.1% Mountain West; 23.7% Pacific West).

Most participants were of Mexican- (68.2%) or Puerto Rican- (18.6%) descent; the majority of participants were born in the U.S. (94.5%). In terms of gender, the majority of respondents were cisgender men (69.5%); 21.2% were cisgender women and 8.5% were transgender or did not identify with the gender binary (note: these 20 participants all identified as sexual minorities). In terms of sexual identity, most participants identified as gay or lesbian (76.3%), 7.2% identified as bisexual, 14.4% identified with other non-heterosexual identity labels (e.g., pansexual, queer), and 1.7% identified as straight or heterosexual but reported same-sex attractions or behaviors.

Measures

All measures were available in English and Spanish (39.8% of participants completed the survey in Spanish). For measures that were not previously available in Spanish (i.e., bias-based school victimization), a back-translation process was used to translate them from English to Spanish (Knight, Roosa, Calderon-Tena, & Gonzales, 2009). A native Spanish-speaker performed the initial translations, which were then back-translated into English by a trained Spanish translator. The two English versions (the original version and the back-translated version) were then compared by a third individual. Minor discrepancies (e.g., conceptual versus literal translation) were identified and resolved by the two authors.

Bias-based school victimization

Bias-based school victimization experiences specific to sexual orientation and ethnicity were each assessed by six items. Reports were assessed by an adapted 6-item measure of self-reports of peer victimization (Little, Jones, Henrich, & Hawley, 2003; Toomey, Card, & Casper, 2014). Sample items include “Kids hit or kick me” and “Kids spread rumors about me.” These items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Never; not at all) to 4 (Always; almost every day). To assess victimization attributed to sexual orientation, each of the statements were followed by the question: “If ever, how often did this occur because people knew or assumed you were lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender?” (Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011). Similarly, to assess victimization attributed to ethnicity, each of the statements were followed by the question: “If ever, how often did this occur because you are Latino/a?” These items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Many times). Prior work has provided support for the validity of the peer victimization items (Toomey et al., 2014) and the follow-up questions that asked about attributions of victimization (Russell et al., 2011). Inter-item reliability was strong for both sexual orientation-related victimization (α = .90) and ethnicity-related victimization (α = .95).

Mindfulness attention and awareness

Mindfulness was assessed using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale – Adolescent (MAAS-A; Brown, West, Loveright, & Biegel, 2011). This scale includes 14 items (e.g., “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until sometime later”) that are scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (almost always). All items are reverse-coded, such that higher scores represent higher levels of mindfulness. A Spanish-version of the MAAS (MAAS-SP) was established by Johnson, Weibe, and Morera (2013), and their study provided support for the validity and reliability with this scale among Latino college students. Inter-item reliability was strong in this sample (α = .88).

Well-being

The two well-being outcomes assessed in this study included depressive symptoms and self-esteem. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale Short Form (CES-D SR; Radloff, 1977). The scale includes 10 items rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most of the time). Prior studies have provided support for the reliability and validity of this measure with Latina/o adolescent populations (Crockett, Randall, Shen, Russell, & Driscoll, 2005). Reliability was acceptable for the current sample (α = .75). Self-esteem was assessed by Rosenberg’s (1979) 10-item Self-Esteem Scale. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Prior studies have demonstrated validity and reliability for Latina/o youth (Supple & Plunkett, 2011). Inter-item reliability was strong in this sample (α = .88).

Academic achievement

Academic achievement was assessed by one question asking about grades (i.e., GPA). A single item assessed GPA: “During the past 12 months, how would you describe the grades you received in school?” Response options ranged from 0 (mostly F’s) to 4 (mostly A’s).

Analytic Procedures

Structural equation modeling in Mplus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) was used for all analyses. Two models were tested: First, a main effects model that examined the direct contributions of minority stress experiences (related to sexual orientation and ethnicity) and mindfulness on well-being and academic achievement. Second, an interaction effects model that examined the interactions between mindfulness with the two indicators of minority stress. All models controlled for age, nativity status (0 = born outside the U.S., 1 = born in the U.S.), Mexican origin status (0 = not of Mexican origin, 1 = of Mexican origin), and gender (two dummy codes for cisgender women and transgender youth compared to cisgender men).

All measures were centered prior to the creation of interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991). Significant interactions were probed at one standard deviation above and below the mean for mindfulness, and simple slopes analyses were examined to further decompose any significant interactions (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML; Arbuckle, 1996). Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Model fit was considered to be good (or acceptable) if the CFI was greater than or equal to .95 (.90), and the RMSEA and the SRMR were less than or equal to .05 (.08) (Little, 2013).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among key study variables are displayed in Table 1. Notably, Latina/o sexual minority youth reported slightly higher levels of victimization related to sexual orientation compared to victimization related to ethnicity (Cohen’s d = .16). Although the bivariate correlation between sexual orientation-based victimization and ethnicity-based victimization is high (r = .86), latent variable nested model testing revealed that the constructs are unique (results are available upon request). Both minority stress experiences were negatively associated with mindfulness, self-esteem, and GPA, while they were also positively associated with depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, however, was positively associated with self-esteem and GPA, and negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Key Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual Orientation Based Victimization | --- | |||||

| 2. Ethnicity Based Victimization | .86 | --- | ||||

| 3. Mindfulness | −.52 | −.50 | --- | |||

| 4. Grade Point Average | −.35 | −.44 | .26 | --- | ||

| 5. Depressive Symptoms | .29 | .24 | −.48 | −.24 | --- | |

| 6. Self-Esteem | −.30 | −.24 | .34 | .25 | −.59 | --- |

| Mean | 1.40 | 1.25 | 3.21 | 2.49 | 2.57 | 1.61 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

Note. All correlations were significant at p < .001 level.

Next, we examined our hypothesized models. Given that the main effects model was saturated (i.e., number of parameters = number of observed information), we constrained non-significant pathways from preliminary analyses to be zero (i.e., the Mexican origin covariate regressed on depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and GPA). The resultant model had good fit: χ2 (df = 3) = 4.248, p = .24; RMSEA = .042 (90% C.I.: .00 − .13); CFI = .995; SRMR = .015. Of the three main independent variables, only mindfulness was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (β = −.49, p < .001) and self-esteem (β = .29, p < .001). GPA, however, was only predicted by victimization related to ethnicity (β = −.32, p < .05), age (β = −.29, p < .001) and gender (women and transgender youth had higher levels of GPA compared to men; β = .19 and β = .24, respectively, both p < .001).

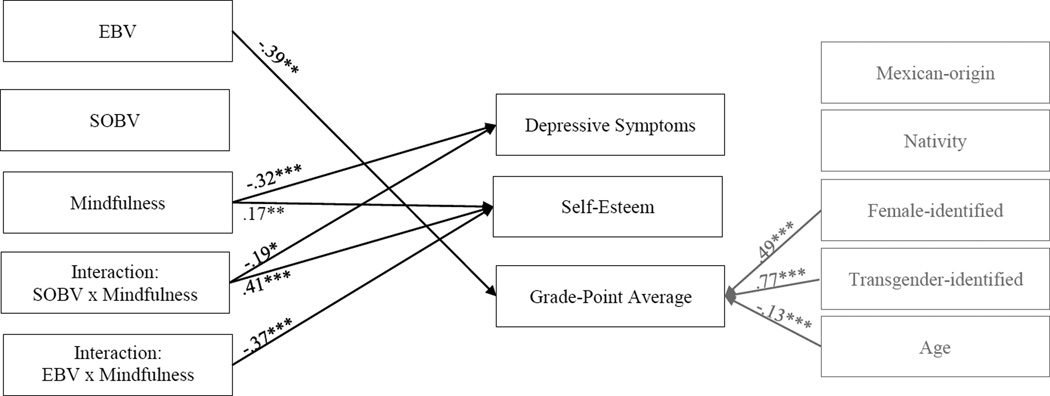

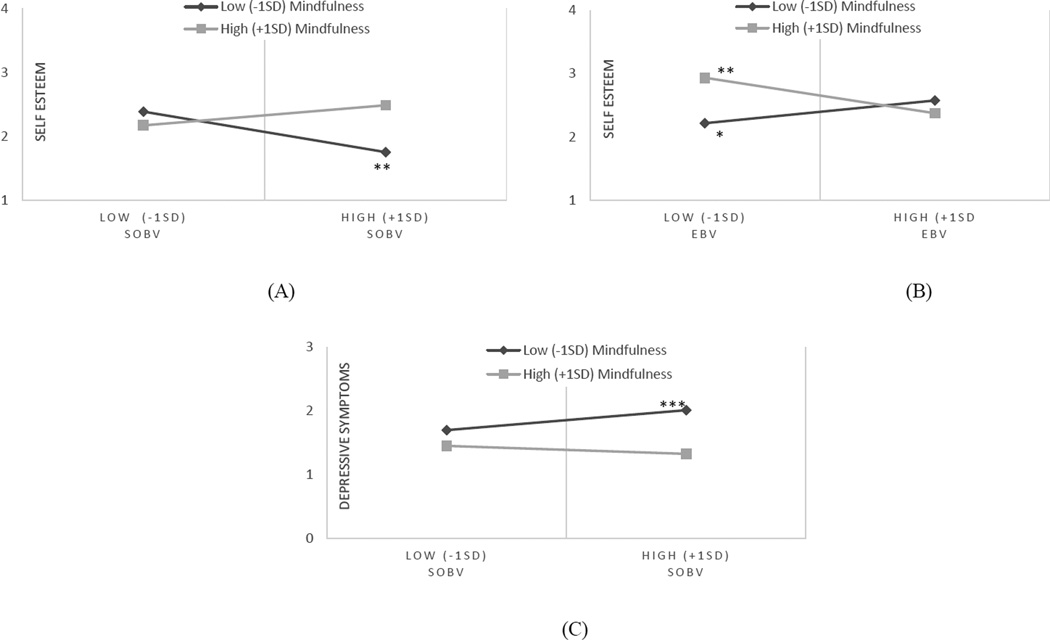

The model that included the interactions had good fit: χ2 (df = 3) = 4.653, p = .199; RMSEA = .049 (90% C.I.: .00 − .13); CFI = .993; SRMR = .012. The findings from this model are displayed in Figure 1. Notably, three out of the six interactions were significant: sexual orientation-based victimization by mindfulness predicting self-esteem (see Figure 2a), ethnicity-based victimization by mindfulness predicting self-esteem (see Figure 2b), and sexual orientation-based victimization by mindfulness predicting depressive symptoms (see Figure 2c). Simple slopes analyses revealed that high levels of mindfulness strategies were protective when the stressor was sexual orientation-based victimization but not ethnicity-based victimization. Specifically, the positive association between sexual orientation-based victimization and depressive symptoms was only significant for those with low levels (−1 SD) of mindfulness (t = 2.037, p < .05). Similarly, the negative association between sexual orientation-based victimization and self-esteem was only significant for those with low levels (−1 SD) of mindfulness (t = −3.90, p < .001). Of note, the simple slope for high levels (+1 SD) of mindfulness was trending significant (t = 1.80, p = .073), suggesting that for youth with high levels of mindfulness, sexual orientation-based victimization was positively associated with self-esteem. Contrary to expectations, for youth with high levels (+1 SD) of mindfulness, there was a negative association between ethnicity-based victimization and self-esteem (t = −2.85, p < .01). Further, there was positive association between ethnicity-based victimization and self-esteem for youth with low levels (−1 SD) of mindfulness (t = 2.19, p < .05).

Figure 1.

Results from a path analysis of ethnicity-based school victimization (EBV), sexual orientation-based school victimization (SOBV), mindfulness, and their respective interactions predicting depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and grade-point average.

Note. Grey font represents covariates, black font represents indicators of main interest. Non-significant paths and covariances are not shown for clarity. Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented. Nativity was coded as 0 = born outside the U.S., 1 = born in the U.S. Mexican-origin was coded as 0 = not Mexican-origin (e.g., Puerto-Rican, Dominican, Columbian), 1 = Mexican-origin. Female-identified was coded as 0 = no, 1 = yes. Transgender-identified as coded as 0 = no, 1 = yes. Male-identified was used as the reference group. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05.

Figure 2.

Plotted significant interactions between (A) sexual orientation-based school victimization (SOBV) and mindfulness predicting self-esteem, (B) ethnicity-based school victimization (EBV) and mindfulness predicting self-esteem, and (C) SOBV and mindfulness predicting depressive symptoms.

Note. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05.

Discussion

The current study examined mindfulness as a potential protective factor against the robust association between school-based victimization related to sexual orientation and ethnicity and self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and GPA among Latina/o sexual minority youth. Our findings suggest that mindfulness may act as a protective-stabilizing factor (Luthar et al., 2000) against school-based victimization related to sexual orientation predicting depressive symptoms and self-esteem. Notably, mindfulness was not associated with GPA, which was only significantly predicted by school-based victimization related to ethnicity. However, for school-based victimization related to ethnicity among Latina/o sexual minority youth, there was a protective but reactive effect (Luthar et al., 2000) for mindfulness, such that mindfulness was protective of self-esteem at low levels of victimization but the protective effect conferred less advantage when victimization was high.

Our bivariate correlational findings were consistent with the extant literature documenting small to moderate associations between minority stress and well-being (Meyer, 2003). The current study extends the examination of the stress → outcome link to address how youth may effectively cope with minority stress. Much of the literature focused on how marginalized youth cope with minority stress (e.g., bias-based victimization, discrimination) has examined youths’ use of avoidance or approach strategies (Brittian et al., 2013; Cheng & Malinckrodt, 2015; Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015; Kuper et al., 2014). Although unexplored in the sexual orientation-focused youth literature, researchers studying ethnic and racial minority youth have found mixed evidence (e.g., Brittian et al., 2013; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2008) for the effectiveness of approach-oriented strategies in moderating the effects of minority stress, and uncontrollable stressor (i.e., discrimination, prejudice, and oppression are systemic features of the youths’ environments). The current study suggests that mindfulness strategies may be beneficial when the stressor at hand is considered uncontrollable. Indeed, mindfulness strategies may be particularly useful given that youth may react or respond to bias-based school victimization in more productive ways rather than reacting to them in a shameful or judgmental way (e.g., Brown et al., 2007; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014). Although not tested in the current study, it may be that increased mindfulness is associated with non-judgmental reactions to experienced oppression via increases in self-compassion (Neff, 2003). As posited by Neff (2003), mindfulness and self-compassion are closely-related processes, such that self-compassion requires that a person respond to stress by acknowledging its existence, without avoidance.

Notably, the protective effects of mindfulness were only evidenced for this study’s mental health-related outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms and self-esteem) and were not found for academic achievement (i.e., GPA). Importantly, the only significant predictor of GPA was ethnicity-based school victimization. This finding is particularly important given the multiple oppressions examined in this study, as it suggests that perhaps minority stress related to ethnicity may be most salient for academic outcomes and minority stress related to sexual orientation may be most salient for mental health outcomes among Latina/o sexual minority youth. This finding is also important in the context that Latino youth are the least likely of all ethnic groups in the U.S. to complete high school (U. S. Department of Education, 2012), providing further evidence for the need to reduce bias, discrimination, and prejudice in the school context for ethnic and racial minority youth.

One explanation for the finding that ethnicity-based school victimization significantly predicted GPA may be related to stereotype threat: a large body of literature suggests that a negative stereotype about a social group, such as underachievement among Latinos, undermines performance among that group’s members and can help to explain gaps in achievement attributed race or ethnicity (Spencer, Logel, & Davies, 2016). While stereotype threats have been well-studied among racial and ethnic minorities specific to academic achievement, they have not been studied for sexual minorities. Indeed, emerging research shows that stereotypes of intelligence are not associated with sexual orientation (Ghavami, 2016). Thus, ethnicity-based minority stress may further exacerbate the stereotype threat for Latinos and result in poor academic achievement, whereas sexual orientation-based minority stress may not be as salient for youth who are both Latina/o and sexual minorities.

Finally, it is important to compare and contrast the differential protective effects of mindfulness for sexual orientation-based minority stress compared to ethnicity-based minority stress. Specifically, mindfulness was a protective-stabilizing factor for sexual orientation-related stress but both a protective and reactive factor for ethnicity-related stress. While these results are promising for interventions focused on sexual orientation, caution needs to be taken to ensure that there are no iatrogenic effects of mindfulness when considering the role of ethnicity and ethnic-based bias in schools.

Notably, other studies have found similar effects with other protective factors for Latina/o youth. For example, Umaña-Taylor, Tynes, Toomey, Williams, and Mitchell (2015) found that ethnic identity affirmation (conceptualized and typically found to be a promotive and protective factor) had a protective but reactive effect when considering the association between discrimination by school adults and self-esteem. In the current study, perhaps being more mindful led to greater salience or awareness of one’s unequal social positioning as an ethnic minority. Thus, the greater awareness of one’s social positioning as an ethnic minority interacting with the experience of victimization attributed to ethnicity may have contributed to greater threats against self-esteem. Indeed, the measure used for mindfulness does not fully capture awareness without judgement (Brown et al., 2011); instead, the measure captures an awareness of what is taking place in the current moment without examining the cognitive appraisals associated with awareness. Further research is needed to understand the cognitive evaluations and levels of self-compassion that one experiences in tandem with mindfulness in relation to ethnic-based victimization.

It may be the case that victimization attributed to sexual orientation did not interact with mindfulness in the same way because the participants interpreted their experiences of victimization related to ethnicity and sexual orientation through different lenses. It may be the case, for instance, that because ethnicity is often visible and non-concealable that more self-judgement is experienced when bias is encountered. On the other hand, because sexual orientation is often considered to be concealable, encountered bias may not be processed as a threat to self via a process of self-judgement. Still, future intersectional research is needed to examine how multiple marginalization experiences, salience of identities, and coping strategies, are associated with a range of outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study is not without limitations. First, and foremost, our study was not longitudinal nor was it experimental; thus, we are unable to truly understand the direction of our positive effects. Further, this was not an intervention study; instead, our examinations focused on existing mindfulness strategies that youth reported. Critical experimental (e.g., mindfulness intervention studies) and longitudinal work is needed to understand protective factors for minority stress, particularly for populations of young people who may experience multiple oppressions. Second, given our small sample size, we were unable to examine moderation by key demographic characteristics (e.g., sexual identity, gender, nativity status) within our sample of Latina/o sexual minority youth. Thus, future studies are needed to understand for whom, where, and when is mindfulness a key protective factor against minority stress. Finally, our sample was primarily comprised of men, suggesting that future research is needed to understand whether mindfulness confers similar protective benefits to women and transgender youth experiencing minority stress related to their sexual orientation or ethnicity.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether mindfulness is a viable coping strategy for dealing with minority stress among youth. Given that mindfulness strategies appear to confer benefit in the context of high risk related to sexual orientation and low risk related to ethnicity (i.e., stabilization of self-esteem and depressive symptoms in the context of high minority stress related to sexual orientation; protective in the context of low minority stress related to ethnicity), our findings suggest that mindfulness might be an effective component of psychosocial prevention and intervention programs focused on sexual minority youth populations. Future intervention research is needed that addresses the protective role of mindfulness for marginalized youth populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the young people who participated in the study. We also thank the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) for their assistance with participant recruitment. [The study was approved by GLSEN’s Research Ethics Review Committee for promotion by GLSEN]. Support for this project was provided by a Loan Repayment Award by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (L60 MD008862; Toomey).

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa MW. A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;65:923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, Plunkett SW, Sands T, Bámaca-Colbert MY. The relationship between Latino adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination, neighborhood risk, and parenting on self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011;42(7):1179–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel GM, Brown KW, Shapiro SL, Schubert CM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0016241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, Hoogstad B, van Dun L, de Schutter S, Restifo K. Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36(02):193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18(4):211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, West AM, Loverich TM, Biegel GM. Assessing adolescent mindfulness: Validation of an adapted mindful attention awareness scale in adolescent normative and psychiatric populations. Psychological Assessment. 2011;4:1023–1033. doi: 10.1037/a0021338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittian AS, Toomey RB, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE. Perceived discrimination, coping strategies, and Mexican origin adolescents' internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Examining the moderating role of gender and cultural orientation. Applied Developmental Science. 2013;17(1):4–19. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2013.748417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HL, Mallinckrodt B. Racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of Hispanic/Latino college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62(1):38–49. doi: 10.1037/cou0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, van Beusekom G, Bos HM, Sandfort TG. Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: A systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50(3–4):299–317. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.750639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen YL, Russell ST, Driscoll AK. Measurement equivalence of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: A national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: Developmental challenges and victimization experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7(4):9–29. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Discrimination and Mexican-origin adolescents’ adjustment: The moderating roles of adolescents’, mothers’, and fathers’ cultural orientations and values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(2):125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BL, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30(1):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M, Adams EM, Waldo M, Hadfield OD, Biegel GM. Effects of a mindfulness group on Latino adolescent students: Examining levels of perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological symptoms. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2014;39(2):145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010 Census briefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_02.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gayner B, Esplen MJ, DeRoche P, Wong J, Bishop S, Kavanagh L, Butler K. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;35:272–285. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, Cunningham Michael. An intersectional approach to examining urban middle school students’ intergroup attitudes about LGB peers of various ethnic groups. Intersectionality and racial-ethnic adolescents; Symposium conducted at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; Baltimore, MD, USA. 2016. (Chair) [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Gibbs J. Strategies employed by sexual minority adolescents to cope with minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2(3):297–306. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargus E, Crane C, Barnhofer T, Williams JMG. Effects of mindfulness on meta-awareness and specificity of describing prodromal symptoms in suicidal depression. Emotion. 2010;10(1):34–42. doi: 10.1037/a0016825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institutes of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CJ, Wiebe JS, Morera OF. The Spanish version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS): Measurement invariance and psychometric properties. Mindfulness. 2014;5(5):552–565. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(2–3):142–167. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Roosa MW, Calderon-Tena CO, Gonzales NA. Methodological issues in research with Latino populations. In: Villarruel FA, Carlo G, Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of U.S. Latino Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Coleman BR, Mustanski BS. Coping with LGBT and racial-ethnic-related stressors: A mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24(4):703–719. [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, Tov W. California Health Kids Survey 2002 analysis. Oakland, CA: Asian Pacific Islander Youth Violence Prevention Center, National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Le TN, Proulx J. Feasibility of mindfulness-based intervention for incarcerated mixed-ethnic Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander youth. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2015;6(2):181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Semple RJ, Rosa D, Miller L. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Results of a pilot study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;22(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K. Coping strategies and health in a national sample of sexual minority women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82:494–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Little T, Henrich C, Jones S, Hawley P. Disentangling the" whys" from the" whats" of aggressive behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27(2):122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Steiner H. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth risks for emotional, physical, and social problems: Results from a community-based survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):297–304. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38(7):985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and identity. 2003;2(3):223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Coll CG. Racism and child health: A review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(3):255–263. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:427–448. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Robers S, Kemp J, Rathbun A, Morgan RE. Indicators of school crime and safety: 2013 (NCES 2014-042/NC] 243299) Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roche C, Kuperminc GP. Acculturative stress and school belonging among Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012;34(1):61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(2):171–184. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Ryan C, Toomey RB, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: Implications for young adult health and adjustment. Journal of School Health. 2011;81:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):493–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23(4):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TG, Bakker F, Schellevis F, Vanwesenbeeck I. Coping styles as mediator of sexual orientation-related health differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(2):253–263. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets RL, Jr, Mohr JJ. Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shilo G, Savaya R. Effects of family and friend support on LGB youths' mental health and sexual orientation milestones. Family Relations. 2011;60(3):318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp SD, Watson RJ, Russell ST, Diaz RM, Ryan C. Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations. 2015;64(3):420–430. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Logel C, Davies PG. Stereotype threat. Annual Review of Psychology. 2016;67:415–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-073115-103235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Gonzalez LM, Huq N. Cultural stressors and the hopelessness model of depressive symptoms in Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41(10):1339–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepler R, Brown A. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 1980–2013. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/05/12/statistical-portrait-of-hispanics-in-the-united-states-1980-2013/

- Supple AJ, Plunkett SW. Dimensionality and validity of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for use with Latino adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2011;33(1):39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Henrichs-Beck C. Exploring sexual minority women’s experiences of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and their links to coping and distress. Sex Roles. 2014;70(1–2):28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Owens GP. Group-level coping as a moderator between heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress in sexual minority women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2009;33(2):197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Card NA, Casper DM. Peers’ perceptions of gender nonconformity associations with overt and relational peer victimization and aggression in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2014;34(4):463–485. doi: 10.1177/0272431613495446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Russell ST. The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis. Youth & Society. 2016;48:176–201. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13483778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(6):1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Tynes BM, Toomey RB, Williams DR, Mitchell KJ. Latino adolescents’ perceived discrimination in online and offline settings: An examination of cultural risk and protective factors. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51(1):87–100. doi: 10.1037/a0038432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, acculturation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Garcia CD, Gonzales-Backen M. A longitudinal examination of Latino adolescents' ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28(1):16–50. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: 1972–2009. 2012 Available at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012006.pdf.

- Zylowska L, Ackerman DL, Yang MH, Futrell JL, Horton NL, Hale TS, Smalley SL. Mindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD a feasibility study. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2008;11(6):737–746. doi: 10.1177/1087054707308502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]