Introduction

Although managing pain in older adults brings unique challenges, older adults who are frail are at greater risk for persistent (also referred to as chronic), acute, or combination pain and ineffectively managed pain. There is no consensus for a definition of frailty; however, frailty represents a state of increased vulnerability to stressors (e.g., pain) and difficulty in returning to a state of homeostasis after a health event. Frail elders show a decline in muscle strength, balance, mobility/physical activity, cognition, endurance, nutrition and weight. These place older adults at risk for persistent pain, co-morbidities, falls, polypharmacy, and delirium. As a result, pain management in frail elders is not only to provide relief and comfort, but also to maintain homeostasis, prevent injury, improve physical and psychosocial function, optimize quality of life, and prevent deconditioning. In addition, considering the impact of pain and associated symptoms on frail elders’ health, they would benefit from a palliative care approach.

Effective pain management consists of accurate identification and assessment of pain and related factors, appropriate tailored treatment, timely evaluation, and clear documentation and communication. Quality pain management becomes even more critical for frail elders with cognitive and mental health impairment, those who experience frequent transitions of care, and those at the end of life. However, limited evidence exists for best practices in pain management in frail elders across the spectrum, primarily because this population is often excluded from research that guides pain practice decisions. This paper presents recommendations for assessment, treatment, evaluation, and documentation of pain in frail elders across the spectrum based on best available evidence.

Clinical Pain Assessment

As in all patients, assessment is a critical first step in pain management in frail elders. Yet pain is under-assessed and under-treated by interdisciplinary healthcare professionals, further decreasing a frail elders’ physical and cognitive reserve.

Several issues contribute to challenges in recognizing and evaluating pain accurately in frail elders including misconceptions related to pain perception, multiple chronic conditions, cognitive and mental health impairment, sensory impairment, and sociocultural influences. A common misconception is that pain sensitivity or perception decreases with aging and/or changes in cognition; however, two paradoxes may occur:

Some older adults, including those with dementia, have a higher pain threshold and higher pain tolerance that contributes to a slower response to pain and a perception of lower pain intensity. These changes may make older adults more vulnerable for unrecognized pain and loss of pain as a warning sign.

In some racial and ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans), pain sensitivity increases with age due to low pain threshold and tolerance levels resulting in a faster recognition of pain and a perception of higher pain intensity. Such differences make these older adults more vulnerable for experiencing severe pain, and pain-related disparities.

Older adults average three or more chronic conditions, many of which are sources of pain (Table 1), placing them at greater risk of experiencing increased pain severity. Sensory, cognitive and mental health impairments, such as dementia, depression, delirium and anxiety, may each and collectively intensify the pain experience and worsen frailty. Be aware that cognitive and mental health disorders alter the expected expression, description, and communication of pain.

Table 1.

Sources of Pain in Frail Elders

| Pathological | Procedural | Adverse Incidents | Trauma & Basic Needs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

Sociocultural background also influences the manner in which older adults interpret, tolerate, respond, and communicate pain. African American and Hispanic/Latino elders experience greater pain-related disparities in assessment and treatment and are more likely to be considered frail because of pronounced burden of co-morbidities. Thus, cultural awareness and responsiveness to pain beliefs and disparities are important for effective pain management.

Assessment Strategies

Internal and external barriers may prevent frail older adults from reporting pain or reporting pain accurately. Selected barriers include wanting to maintain a sense of control, beliefs about pain, feeling ignored or misunderstood, inability to communicate pain experience, and inadequate communication between healthcare providers. The PENS (Pain, Expectations/Emotions, Nutrition, Sleep) acronym (developed by Mark Greenwood) is one approach to guide pain assessment in frail older adults. PENS was originally developed as a patient-provider communication tool to manage pain and suffering, improve transparent and effective communication between patients, healthcare providers, and caregivers, and target pain-related factors particularly relevant for vulnerable older adults.

Pain

Skillful comprehensive assessments are needed to determine pain in frail elders given their likelihood for atypical presentation of pain. Frailty should be assessed in all older adults with pain using a screening tool like the EASY-Care Two-step Older persons Screening (EASY-Care TOS). Review patients’ medical history to identify potentially painful conditions and recognize that older adults may display other signs related to pain, including fatigue, inability to sleep, loss of appetite, and delirium.

Step 1: Determine if older adult can self-report pain. When feasible, self-report is the most reliable source of information. Most older adults with mild-moderate cognitive impairment can self-report pain at some level; determine if the older adult can reliably self-report using a pain scale by asking them to place a mark where severe pain is represented and evaluate for logical placement. If older adult can self-report, move to Step 1A; if they are unable to self-report, skip to Step 1B.

Step 1A: If older adult can self-report pain, assess characteristics of pain:

Pain present or absent: Ask simple questions incorporating language beyond “pain”, such as “Are you experiencing any pain or discomfort right now?”, “Do you feel sore or achy anywhere on your body?”, or “Tell me about your pain or discomfort.” Provide adequate time for frail elders to respond and describe pain, as their energy and cognitive reserve are lowered.

Source or cause: Chronic conditions known to be painful, acute injury or trauma, discomfort from procedures or other causes.

Intensity: Use a valid and reliable self-report pain assessment tools to measure intensity (numerical or descriptive) in self-reporting older adults. Because frail elders may have issues with focus and concentration due to weakness and exhaustion, offer pain tools that are less demanding (e.g., shorter and easier to understand), but can also demonstrate nursing-sensitive quality indicators. Older adults in general prefer verbal descriptor scales, such as the Iowa Pain Thermometer-revised (IPT-r), and those from different ethnic groups, including African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian, prefer the Faces Pain Scale-revised (FPS-r), although individual differences in preference occur and should be confirmed.

Tolerability: The perception of tolerability by the older adult and impact of pain on function (e.g., activities of daily living, rehabilitative therapy) are important in treatment planning. Use the Functional Pain Scale to evaluate tolerability and impact of pain on passive and active functions.

Quality (e.g., burning, dull, sharp, ache, pricking): Although quality descriptors help determine if pain is nociceptive or neuropathic, it may be impossible to gather this information in older adults with cognitive impairments.

Location (e.g., localized, regional, generalized/widespread): Frail elders may have difficulty localizing pain or evaluating generalized/widespread pain. They may also find it challenging to identify the timing and aggravating and relieving factors of pain.

For older adult able to self-report, continue with PENS, moving on to

Expectations/Emotions

Step 1B: In older adults with delirium and severe cognitive impairment unable to self-report, alternative approaches to pain assessment are needed.

Search for potential sources of pain common in frail elders including co-morbidities, relevant diagnoses, other unpleasant conditions that might be overlooked (See Table 1).

Observe for pain-related behaviors, such as grimacing, moaning, postural changes, and use the PAINAD or other valid/reliable pain behavior tool (Visit http://prc.coh.org/PAIN-NOA.htm for a complete list of pain behavior tools). Pain behavior tools assess the presence of behaviors that may be pain-related and increases or decreases in behaviors. It should be clear that documentation of a behavior score from a pain behavior tool is not comparable to a pain intensity score on a numeric rating scale. Other factors that may result in similar behaviors, such as delirium, should be ruled out. The presence of delirium should trigger assessment for possible un- and under-treated pain. Staff should be educated to use the selected tool to establish baseline behavior and monitor for changes suggestive of pain, evaluate response to treatment with the same tool across transitions and settings, and incorporate into institutional procedures for assessing pain in nonverbal older adults.

Obtain proxy-report from family or professional caregivers or unlicensed personnel (e.g., nurses’ assistants) on changes in activities and/or function in the older adult that may be pain-related. Nurses’ assistants can use a pain behavior scale to screen for possible pain, referring to nurse for thorough assessment.

Initiate and evaluate a time-limited analgesic trial starting with acetaminophen, if there is suspicion pain is present or if pain behaviors persist after addressing basic physiological needs and implementing comfort measures (Table 2). Nurses’ decision to treat pain in older adults with dementia is usually linked to a change in behavior. Because homeostasis in frail elders is already compromised combined with delayed recognition of pain in cognitive impairment, improvement in pain behaviors may be prolonged. If behaviors improve, assume pain was the cause and complete a risk/benefit analysis to determine the best treatment plan going forward that incorporates the safest complementary interventions and analgesics, if needed.

Table 2.

Analgesic Trial for Suspected Pain in Non-communicative, Cognitively Impaired Older Adults

Initiate an empiric analgesic trial if:

|

| Provide a step-wise analgesic trial and titration appropriate to the estimated intensity of pain based on instances above, severity of behaviors, analgesic history, and prior assessment.

|

© 2014 Herr K, Booker S, Bartoszczyk D. “Analgesic Trial for Suspected Pain in Non-communicative, Cognitively Impaired Older Adults.” Adapted and used with permission from Herr K, Coyne P, McCaffery M, et al. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010;12(4): 230-50.

Expectations and Emotions

Determine realistic expectations and goals:

Ask “What are your expectations for pain relief?” if older adult can self-report.

Develop a comfort-function-mood goal(s) by determining acceptable levels of pain and goals for daily functional activity and mood improvement/maintenance. Zero pain is often not a realistic goal.

Engage family and caregivers when frail elder is unable to develop a comfort-function-mood goal.

Frail elders are at greater risk for psychosocial function decline and the need to evaluate and maintain or improve mood is an important goal. Depression and anxiety are often present and both exacerbate the experience of pain. On the other hand, depression may also prevent frail elders from reporting pain.

Use simple questioning to ask about mood in addition to valid assessment scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (available at hartfordign.org).

Nutrition

Altered nutrition is associated with un- and under-treated pain, and can be further complicated in frail older adults who are already undernourished and present with anorexia of aging. Their appetite may be less robust and weight extremely low, and this level of nutritional status impacts pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics.

Ask about nausea, hunger or thirst, or if patient has eaten. Patients with nausea may be unable to consume oral pain medications. On the other hand, behaviors thought to be pain-related may, in fact, be related to basic needs such as food and water.

When unable to self-report, observe patterns of eating and elimination to establish a baseline and any changes in baseline.

Weigh patients regularly as this impacts medication dosages.

Monitor bowel and bladder elimination as this will also impact elimination of medication. For example, existing constipation may limit use of opioids which are known to cause constipation or necessitate an increased bowel regimen.

Sleep

Insufficient sleep is shown to significantly impact existing pain and development of widespread pain in older adults. Assess impact and interference of pain on sleep by asking:

“Have you been sleeping well?” and “Does your pain affect your ability to fall asleep or stay asleep?”

When unable to self-report, observe and monitor sleep patterns to establish baseline sleep behavior, which may include existing insomnia not related to pain. Changes in baseline behavior may clue nurses to pain a potential cause.

Use the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index for formal measurement, available at hartfordign.org.

Clinical Pain Treatment

Optimal treatment of pain in frail elders is challenging because of a lack of evidence and existing research gaps for this vulnerable population. However, clinical guidelines for managing pain in older adults, such as those from the American Geriatrics Society and the British Pain Society/British Geriatrics Society, provide recommendations that can be applied to frail elders. Issues related to frailty level, multi-morbidity, past/current medications, medication availability, polypharmacy, potential treatment risks, cognitive and functional status, and available social support must be considered in meeting patient preferences and goals. Initiate treatment as soon as possible in order to maximize effectiveness after individualizing the comfort-function-mood goal for pain management. Advanced directives stating treatment preferences may be useful as well, particularly at the end-of-life.

The new Institute of Medicine report, Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near End of Life, highlights the importance of pain management in older adults near death, given that up to 46% of older adults suffer from pain during the last month of life. End-of-life circumstances impact decision-making regarding pain treatment goals and choices, and the frail elder’s treatment choices should be honored, even if there are risks related to use of opioids necessary to assure relief from pain and suffering during life’s final stages. During end-of-life, pain medications may need to be given via oral transmucosal, rectal, subcutaneous access port, or vaginal. The intramuscular route should not be used in any older adult for pain treatment, and is particularly problematic in frail elders whose body composition limits effective absorption and distribution of analgesics. Palliative sedation for unmanageable pain and suffering is an available option that frail elders and caregivers may consider.

Developing the geriatric interdisciplinary treatment “team”. The complexity of pain in the frail elder warrants an interdisciplinary team approach that includes not only nurses, physicians, pharmacists, social workers, but also physical and occupational therapists to maintain function, recreational therapist for therapeutic activities to maintain or improve psychological and social function, a nutritionist for individualized meal planning to prevent further undernourishment, pastoral care for spiritual guidance, and caregivers to support implementation of multimodal pain treatment. Remember that frail elders rely heavily on the assistance of caregivers and personal assistants in order to utilize interventions; thus, consider and assess caregivers’ educational, financial, and emotional needs and ability to assess/re-assess pain and administer treatments safely.

Approaches to Treatment

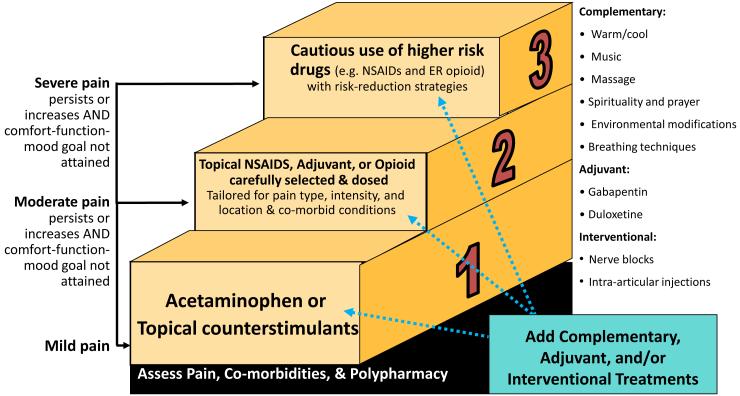

A systematic approach can assist in planning and implementing appropriate multimodal treatment. A multimodal approach utilizes a combination of complementary treatments along with pharmacological treatments, if needed. This approach minimizes reliance on medications and decreases potential side effects and adverse effects. Figure 1 illustrates considerations for treatment options for different levels of pain intensity.

Figure 1.

Selected Examples of Treatment Interventions for Frail Older Adults

© 2014. Herr, K., Booker, S., & Bartoszczyk, D. “Stepped Treatment Approach for Older Adults.”

Complementary treatment

Complementary treatments require careful consideration when used with frail elders in order to assure appropriateness given the individual’s limitations and capabilities and safety considerations. Multiple chronic conditions, cognitive limitations, and physical impairments impact use of various strategies. For example, cognitive challenges and loss of ability to understand instructions make progressive relaxation and guided imagery difficult to implement. More passive activities, such as simple relaxation techniques using massage and/or heat, are often useful. However, frail elders with sensitive and thinner skin are at risk for skin damage with cold-heat applications, necessitating careful monitoring when used. Following are examples of complementary interventions for pain relief in frail elderly who may be experiencing exhaustion, weakness, and fatigue:

Simple cognitive behavioral techniques such as education, distraction, reminiscence therapy, and selected coping strategies.

Relaxation techniques such as music therapy, humor, paced breathing.

Pet visitation and animal assisted therapy.

Physical interventions, including cold-heat applications, therapeutic massage, position changes, assistive devices, pressure relieving and redistribution devices, and assistive devices.

Movement therapies including exercise in the form of simple movements such as passive range of motion, Tai Chi, and physical therapy.

Spiritual interventions, such as prayer and mindfulness meditation.

Nutrition supplements and herbal preparations.

Environment modifications such as noise and light reduction, aromatherapy, rest, sleep protocol and valuable interpersonal interactions.

Pharmacological treatment

Prior to initiating pharmacological treatment, a risk/benefit analysis is particularly important for frail elders with increased vulnerability to analgesic adverse effects. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, multiple chronic conditions that increase potential for adverse effects, polypharmacy, and misconceptions about pain medications impact treatment success.

Changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in frail elders are expressed in alternations in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. For example, increase in fat: water ratio, decrease in plasma protein such as albumin, and impaired liver and kidney function lead to unpredictable responses to medications and thus, a need for lower doses and careful monitoring for adverse effects. Obtain baseline lab values for renal and liver function. Undernourishment and sarcopenia common in frail elders also impact pharmacokinetics and increase risk. Also consider the impact of pharmacogenetics, as this can affect treatment metabolism, response, and effectiveness. It is always best to tailor treatments and individually evaluate effectiveness. The accepted principle of pharmacological treatment in older adults, careful dosing (start low), titration (go slow), and therapeutic evaluation (get to goal), is particularly important in the vulnerable frail elder.

Frail elders have multiple chronic diseases and consequently take multiple medications (i.e., polypharmacy), increasing the risk of adverse effects. Medications may be unnecessary or inappropriate, have dangerous drug-drug or drug-disease interactions, or overlap in mechanism of action. The American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria updated in 2012 identifies medications inappropriate for older adults, typically because of drug-drug or drug-disease interactions. Medications used for pain treatment that should be avoided (or used with caution) in older people, particularly frail elders, include meperidine (Demerol), non-COX-selective NSAID (e.g., Aspirin >325 mg/day), Cox-1 selective NSAIDs (e.g. indomethacin, ketorolac), pentazocine, skeletal muscle relaxants, and many of the short and long acting benzodiazepines. Morphine is an additional medication that should be used cautiously in older adults and those with renal or hepatic impairments considering that the active metabolite may increase risk for toxicity and delirium. Although concerns vary based on the specific drug, these medications place older adults at greater risk of GI bleeding, confusion, hallucinations, kidney injury, and falls and fractures. Acetaminophen is recommended as the first line of treatment in mild pain, but recent FDA concerns have led to dosing recommendation changes. However, acetaminophen remains safe to use as long as 24-hour dose does not exceed 4000 mg in healthy older adults or 2000-3000 mg in frail older adults due to increased risk for liver toxicity. Perform a detailed medication history to identify redundant and inappropriate medications, as well as previously used treatments that were successful in treating pain.

Use of opioids requires careful consideration in frail older adults. Recent evidence raises concerns about increased risk of falls, particularly since impaired gait is common in frailty, cognitive changes, and adverse effects related to long-term use, although there is limited evidence in frail elders. However, opioid therapy may still be a reasonable choice for those whose pain is severe enough to impact function and quality of life, following a discussion with the elder and/or family regarding risk/benefit analysis. For opioid naïve older adults, careful dosing and monitoring is essential, starting with 25-50% of the adult starting dose, using short acting opioids first, and increasing the dosage slowly until the desired pain management relief goal is achieved. Also, anyone on opioids should be screened for risk of addiction/substance abuse. Impact on function and development of tolerance, dependence, adverse effects, or addiction guides adjustment and continuation of opioid therapy. There is currently no good evidence to use an equianalgesic chart when changing from one opioid to another in frail elders, but is still commonly used as a guide.

Anticipating, monitoring, and treating side effects, such as nausea, constipation, and sedation, or adverse effects are essential for successful pain management. For example, when opioids are used, ensure a bowel regimen is in place for opioid-induced constipation (OIC) and consider using a bowel performance scale. Although uncommon, an airway management plan for opioid-induced sedation and respiratory depression (OID) should be in place. Fall precautions when using sedating pain medications and bleeding precautions if using NSAIDs for an extended period of time should also be implemented.

Clinical Pain Evaluation

Timely reassessment and evaluation is essential to monitor for improvement or deterioration in pain or function, adverse effects, and to optimize pain management. Although change in pain intensity level is often used to verify treatment effectiveness, it is also important to:

Evaluate attainment or progression toward comfort-function-mood goals. Reinforce positive outcomes, such as decreases in pain intensity, ability to ambulate/increase in function, and decreased sleep disturbances due to pain.

Decrease in pain suggestive behaviors, agitation, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms displayed by some with cognitive impairment.

Implement a risk evaluation and mitigation surveillance program to determine treatment effectiveness, tolerability, adherence, and dose sensitivity.

Assess need for additional patient/caregiver pain management education.

Clinical Pain Communication and Documentation

Recognizing the importance of communication on patient outcomes, the Joint Commission provides recommendations for advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care. Written, electronic, and verbal communication of the pain management plan must be consistent and accurate. This is especially important for frail elders experiencing frequent transitions between levels of care and care settings. More often than not, communication of pertinent information is not reported between transitions of care contributing to fragmented treatment planning and poor pain outcomes for frail elders. Essential information to be communicated during transitions of care includes pain management history, assessment tools and scales used, complementary and pharmacological interventions tried and shown effective and/or ineffective, and patient goals for pain outcomes. Clinical decision-making tools, such as electronic health record alerts regarding inappropriate or high alert medication, flag alerts for frail elders, and embedded standard communication and pain assessment tools may help facilitate effective communication and documentation.

Summary

This paper has discussed the challenges and strategies for optimizing pain management in frail elders. Effective pain management is an ongoing team effort that entails accurate assessment, best selection and careful monitoring of multi-modal treatments, evaluation of treatment, and clear documentation. Frail elders deserve quality pain management and a thoughtful approach can promote this.

References

- Arnstein P. Clinical coach for effective pain management. F.A. Davis Company; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein P, Keela H. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies for older adults with persistent pain. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(4):56–65. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130221-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. JAGS. 2009;57:1331–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. *Classic reference and Latest recommendations.* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. Accessed on September 20, 2014 http://www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/beers/2012BeersCriteria_JAGS.pdf.

- Gammons V, Caswell G. Older people and barriers to self-reporting of chronic pain. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(5):274–278. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.5.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood MJ, Bennett EJ. The PENS acronym in emergency medicine and nursing: A structured communication tool to manage pain and suffering. Intl Emerg Nurs. 2014;22:239. [Google Scholar]

- Herr K. Pain assessment strategies in older patients. J Pain. 2011;12(3, Suppl 1):S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near end of life. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzyna D, Jungquist CR, Pasero C, et al. American Society for Pain Management Nursing guidelines on monitoring opioid-induced sedation and respiratory depression. Pain Manage Nurs. 2011;12(3):118–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koponen MPH, Bell JS, Karttunen NM, et al. Analgesic use and frailty among community-dwelling older people. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(2):129–36. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris UE, Abrams RC, Gurland B, Reid MC. Management of persistent pain in the older adult: A clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(8):825–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan AJ, Bath S, Naganathan V, et al. Clinical pharmacology of analgesic medicines in older people: Impact of frailty and cognitive impairment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(3):351–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton IR, Terrill AL. Overview of persistent pain in older adults. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):197–207. doi: 10.1037/a0035794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacological assessment. Mosby Elsevier; St. Louis, MI: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan-Colwell A, D’Arcy Y. Compact clinical guide to geriatric pain management: An evidence-based approach for nurses. Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Herr KA, Pacala JT, et al., editors. Geriatrics at your fingertips. The American Geriatrics Society; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi R, Meek BD. Management of chronic pain in elderly, frail patients: Finding a suitable, personalized method of control. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:37–46. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S30165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shega JW, Dale W, Andrew M, et al. Persistent pain and frailty: A case for homeostenosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, Cenzer IS, Knight SJ, et al. The epidemiology of pain during the last 2 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(9):563–9. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen JAL, Schers HJ, Melis RJF, et al. Construct validity and reliability of a two-step tool for the identification of frail older people in primary care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(2):176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]