Abstract

Background

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is widely used for the genetic analysis of neuronal cell biology, development, and behavior. Because traditional methods for evaluating behavioral phenotypes are qualitative and imprecise, there is a need for tools that allow quantitation and standardization of C. elegans behavioral assays.

Results

Here we describe a tracking and imaging system for the automated analysis of C. elegans morphology and behavior. Using this system, it is possible to record the behavior of individual nematodes over long time periods and quantify 144 specific phenotypic parameters.

Conclusions

These tools for phenotypic analysis will provide reliable, comprehensive scoring of a wide range of behavioral abnormalities, and will make it possible to standardize assays such that behavioral data from different labs can readily be compared. In addition, this system will facilitate high-throughput collection of phenotypic data that can ultimately be used to generate a comprehensive database of C. elegans phenotypic information.

Availability

The hardware configuration and software for the system are available from wschafer@ucsd.edu.

Background

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is among the most widely studied genetically-tractable experimental organisms. C. elegans is a soil-dwelling animal with a relatively simple and extremely well characterized anatomy; an adult hermaphrodite, for example, contains exactly 959 somatic cells, each with an identified position, morphology and cell lineage. Because of its short generation time, amenability to germline transformation, and completely sequence genome, it is ideally suited for classical and molecular genetic analysis. In particular, since the C. elegans nervous system is simple and well-characterized (the identity and connectivity of each neuron is known), it has become a facile model for studying the molecular basis for nervous system function. Robust behavioral phenotypes have been described for many C. elegans behaviors, including locomotion, egg-laying, mating and feeding, and these phenotypes have proven extremely useful for the genetic dissection of key aspects of neuronal function such as synaptic release, sensory transduction, and neuromuscular signalling [1].

Historically, a major limitation of such neurobiological studies in C. elegans has been the lack of quantitative methods for the evaluation of behavioral phenotypes. For example, the phenotypes of many behavioral mutants, even those defective in key aspects of neuronal signal transduction, appear subtle to a real-time human observer, and are difficult to assay without time and labor-intensive analysis of video recordings [2-4]. Even the phenotypes of mutants with grossly abnormal behavior are difficult to characterize precisely by manual observation. For example, mutants with striking defects in locomotion (uncoordinated, or Unc mutants) are typically classified using qualitative terms such as "coiler", "kinker", "sluggish", "slow" and "loopy" [5,6]. Since these descriptions are imprecise and subjective, it is extremely difficult if not impossible to assess the phenotypic similarity between two mutants based solely on such characterizations. Another challenge occurs in the analysis of behaviors such as locomotion and egg-laying, which can fluctuate over long time scales or involve infrequently-occurring events that are difficult to evaluate through real-time observation [7]. Furthermore, the quantitative assays that have been used in C. elegans behavioral studies (e.g. [8]) generally differ from lab to lab, and this lack of standardization has made effective comparison of data collected by different researchers difficult.

To address these problems, we have developed an automated tracking and image analysis system for the quantification of C. elegans behavioral patterns. Using this system, it is possible to record the behavior of individual animals at high magnification over long time periods and to simultaneously quantify a large number of behaviorally-relevant features for subsequent analysis. This system has wide applications for the dissection of complex C. elegans behaviors, and will also make it possible to comprehensively classify the behavioral patterns of C. elegans mutants on a genome-wide scale. By making this system widely available to C. elegans neuroscientists, we intend to define a software architecture that can be continually optimized and upgraded to incorporate new parameters that are useful to worm researchers, as well as a hardware platform that can be expanded to provide additional mechanical capabilities for the research community.

Methods

To effectively capture the locomotion behavior of a freely-moving worm, it is necessary to acquire a sequence of images from which the animal's position, speed and body posture at any given point in time can be derived. C. elegans are small (1 mm) animals which, in the laboratory, are normally cultured on agar plates covered with a lawn of the common laboratory bacterium Escherichia coli. Nematodes move using an approximately sinusoidal wave motion that is propagated along the anterior/posterior axis in the dorsal/ventral plane. On an agar plate, the animal will normally lie on either its left or right lateral surface, making the waveform associated with movement visible from above. When crawling at maximum speed, an adult nematode travels at a rate of approximately 500 μm/s; thus, under the relatively high magnification (40–50 X) required to measure detailed features of body posture the worm can quickly crawl outside the field of view. It is therefore necessary to incorporate into the imaging system a motorized stage that can automatically follow the animal's movements and keep it in the microscope's visual field.

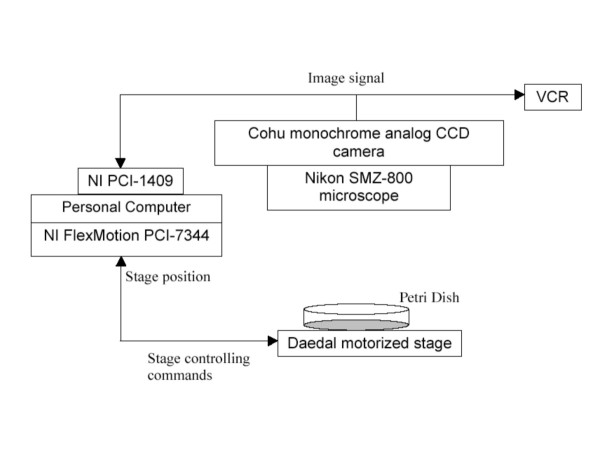

The tracking system described here consists of (i) a Nikon SMZ-800 microscope with a stereoscopic zoom, for visualizing the animals; (ii) a Daedal motorized stage controlled by a National Instruments 4-axis controller, for maintaining the animal in the visual field; (iii) a Cohu monochrome analog CCD camera, for image acquisition; (iv) a Windows computer (PC) with a National Instruments video acquisition board, for tracking and image analysis (Figure 1). An optional VCR can also be included in the system for the purpose of cross verification of behavioral tracking. A complete parts list is in Additional file 1 ("hardware"). It should be noted that the software (see below) can, with very minor revisions, be adapted to other programmable motorized stages and frame grabbers that meet the industrial standards; questions about specific pieces of equipment can be addressed to the authors.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the hardware of tracking system. A Nikon SMZ-800 microscope with a stereoscopic zoom is used to visualize the animals. Image signal can be simultaneously captured by a VCR and digitalized by a NI PCI-1409 image capture board through a Cohu monochrome analog CCD camera. NI FlexMotion PCI-1744 stage controller controls the Deadal motorized stage to follow the animal, and receives the stage position information.

Software

Briefly, the software for the system consists of four basic modules. The first module, called the tracker, allows the system to follow the worm as it crawls around the plate by directing the movements of a motorized stage to maintain the animal in the center of the field of view. As the video acquisition board acquires digital images from the microscope field, the tracker program identifies the animal from each acquired image based on 1. size of the objective isolated from background and 2. the direction of the animal crawling in previous frame if more than two objectives are found Based on the coordinates of the animal's centroid within the field of view, the tracker directs the movements of the stage to recenter the animal in the visual field when animals approach the edge of the image frame. The program then saves an image (460 × 380) of the worm containing visual frame (i.e, the pixels composing the worm body plus the minimum enclosing rectangle), the position of the animal within the field of view, the position of the stage, the time the image was captured, and other information crucial for behavioral analysis. These data are saved into the widely used .avi multimedia format, with a MPEG-4 filter to significantly compress the size of data. Null images are not saved into the .avi format, and the user is notified of the null frame. The highest frame rate with which the tracker can perform these operations with our current hardware setting is 30 frame/sec.

Next, the system contains a module (called the converter) that processes the raw images to simplify parameter estimation. First, the grayscale image is thresholded and converted to a binary image representing the worm outline. The image is further simplified by generating a morphological skeleton along the midline of each binary image and then distributing 30 skeleton points along this skeleton. A third module (called Lineup) then orders the backbone points from head to tail. To distinguish head and tail, minor user input is required to achieve 100% accuracy. In wild type, this user input (which involves identifying the head with a mouse click) is only required on 1% of the frames. Otherwise, all image processing is completely automated.

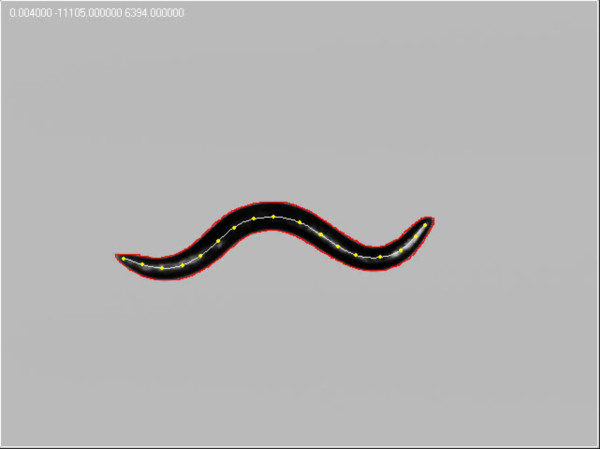

Thus, for each raw acquired image, the system generates 4 representations of the animal (Figure 2) of increasing complexity: the centroid representing the animal's position, the set of ordered skeleton points representing the animal's body posture, the binary image, which provides information about the size and shape of the animal, and the grayscale image, which retains information about the translucency of the animal. Together the outputs of the first three modules then are used to extract quantitative image features that define the characteristic behavioral pattern of a particular mutant type. During image processing stage, aberrant frames (e.g. containing a 'worm' with suddenly abnormal length) are marked and removed, and the user is notified of the defective image.

Figure 2.

Representations of the C. elegans animal. The image is recovered from avi file. The Red line shows the boundary of the binary image. The skeleton is shown in white line and the yellow dots represent the skeleton points.

To obtain this information, the system has a fourth, parameter estimation module (called miner) that measures specific features based on grey/binary image, centroid, or skeleton point analysis that define important parameters related to locomotion or morphology. Broadly speaking, these include measurements of morphology, body posture, movement, and locomotion waveform. Morphological features include measurements of size, length, transparency, and elongation/eccentricity. Body posture features include measurements of body curvature as well as the occurrence of specific postures such as coils and omega turns. Movement features include centroid-based measurements of global speed and direction, skeleton point-based measures of local movement, and the occurrence of directional reversals and large turns. Waveform features include measurements of the frequency and amplitude of body bends, the flex of the animal's body during the locomotion wave, and the frequency and magnitude of foraging movements by the animal's nose. A total of 59 distinct features (Table 1) are measured by the system. For most of these features, three statistics (top 5% as maximum, mean and lower 5% as minimum) are calculated for each recording, giving a total of 144 measured parameters. A list of all the features and the algorithms used to generate them are found in supplemental data [see Additional file 2 "algorithms"].

Table 1.

Features measured by the automated system. List of the behavioral and morphological features. Detail algorithms to output these features are found in supplemental data. 144 statistical results (mean, maximum and minimum where applicable) of these features are output into Microsoft Access, while the values of these feature at each time when an image is grabbed are saved in Microsoft Excel.

| Features | Comments | Catalog |

| Area | Total area of worm | Body morphology |

| BendingFrequency | Frequency of body bends | Wave form/speed |

| CmptFactor | Compactness factor | Body posture |

| ElgFactor | Elongation factor | Body posture |

| EllMAxis | Best-fit ellipse, major axis | Body posture |

| EllRatio | Best-fit ellipse, major axis/minor axis | Body posture |

| EqvlEllRatio | Equivalent ellipse ratio | Body posture |

| Fatness | Area/Length | Body morphology |

| Flex | Maximum skeleton point angle difference | Wave form |

| Foraging | Frequency of sideways (foraging) head movements | Specific behavior (feeding) |

| Foraging angle | Angle of foraging movements | Specific behavior (feeding) |

| Foraging distance | Distance moved by head during foraging | Specific behavior (feeding) |

| FRE | Frequency of angle change between skeleton points | Wave form/speed |

| GlbMvScope | Maximum distance moved from starting point | Global movement |

| GlbSpd | Speed of the animal's centroid movement | Global movement |

| HdTlRatio | Ratio of head to tail movement speed | Head movement |

| Heywood | Heywood circularity factor | Body morphology |

| Hydraulic | Hydraulic radius | Body morphology |

| IXX | Inertia XX | Body morphology |

| IXY | Inertia YY | Body morphology |

| IYY | Inertia XY | Body morphology |

| LclSpd | Local movement speed | Local speed |

| Length | Distance from head to tail | Body morphology/posture |

| LengthToPixel | Length/number of pixels in skeleton | Body posture |

| Loop | Percentage of time worms coils their body | Specific behavior (coil) |

| MaxIntercept | Max intercept | Body morphology |

| MeanIntcptPpdcl | Mean perpendicular intercept | Body morphology |

| MostPopularArea | Mode of area | Body morphology |

| MostPopularSpeed | Mode of speed | Global speed |

| PercentageMPArea | Frequency of occurrence of modal area | Body morphology |

| PercentageMPSpeed | Frequency of occurrence of modal speed | Global speed |

| Pushing | Local body movement speed/centroid speed | Locomotion wave efficiency |

| RectBigSide | Minimum enclosing rectangle (MER) length | Body posture |

| RectRatio | Minimum enclosing rectangle length/width ratio | Body posture |

| Reversal | Percentage of time that a worm performs reversals | Specific behavior (escape) |

| ReversalCount | Number of reversal sessions that a worm performs | Specific behavior (escape) |

| ReversalDisAve | Average distance traveled backward in reversals | Specific behavior (escape) |

| SktAglAve | Mean value of skeleton point vector angle | Body bending |

| SktCmptFactor | Length of worm / oriented MER area | Body posture |

| SktElgFactor | Skeleton enlongation factor | Body posture |

| SktHight | Oriented MER height | Body posture |

| SktIXX | Sum of x coordinate times x coordinates of skeleton points | Body posture |

| SktIXY | Sum of x coordinate times y coordinates of skeleton points | Body posture |

| SktIYY | Sum of y coordinate times y coordinates of skeleton points | Body posture |

| SktvAglAve | Average angle between skeleton points and centroid | Body bending |

| SktvAglMax | Max angle between skeleton points and centroid | Body bending |

| SktvDisAveToLength | Average distance between skeleton points and centroid/length | Body bending |

| SktvDisMaxToLength | Max distance between skeleton points and centroid/length | Body bending |

| SktvDisMinToLength | Min distance between skeleton points and centroid/length | Body bending |

| SktWidth | Oriented MER width | Body posture |

| Theta | Direction of centroid movement | Global movement |

| Thickness | Thickness of worm | Body morphology |

| TotalTravelDistance | Total distance traveled by a worm | Global movement |

| TrackAmplitude | Amplitude of waves in worm's track | Wave form |

| TrackWavlength | Wavelength of waves in worm's track | Wave form |

| Transparency | Transparency of worm body | Body morphology |

| Turn | Percentage of time that a worm performs a sharp turn | Specific behavior (search) |

| TypeFactor | Type Factor | Body morphology |

| Waddel | Waddel disk diameter | Body morphology |

| WaveLenth | Largest spatial span of a sine wave | Wave form |

| XSym | Sum of X coordinates of all sktps | Body bending |

| XYSym | Sum f Y coordinates of all sktps | Body bending |

| YSym | Sum of X coordinate * absolute value of Y coordinate | Body bending |

Implementation

The software is available in a PC version (compiled and benchmarked on a PC with 1 G Hz Pentium-III running Windows 2000 or XP). Software is written with C/C++, Labview 7.0 and Matlab (release 13), and complied with NI LabWindow 7.0. Installation disk and dataset samples are available upon request for non-profit academic usage with a license fee ($75, charged by National Instruments for the usage of their vision library; see Additional file 3 and 4, "codes" and "filelist" for details). Worm behavioral image data are in AVI format with a standard MPEG-4 filter (Microsoft MPEG-4 v2). Quantitative morphological and behavioral data are outputted into two widely distributed formats: Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Access. Using this hardware configuration, it is possible to process a 2 Hz 1 min real time data set in less than 5 minute (from image data to final data). Thus, it is feasible to envision using the system to screen for specific behavioral phenotypes among mutagenized C. elegans.

Applications

We describe here a prototype for a standard, open-source system for automated phenotypic analysis of C. elegans behavior. We anticipate that such a system will be extremely useful to C. elegans neurobiologists, as machine vision offers a number of clear advantages over real-time observation for the characterization of behavioral phenotypes. First, it provides a precise definition of a particular mutant phenotype, facilitating quantitative comparisons between different mutant strains. For example, the waveform parameters have provided detailed information about the effects of neuronal G-protein signalling pathway genes on locomotion behavior. Even phenotypes that are extremely difficult to distinguish by eye (e.g. those of the calcium channel mutants unc-2 and unc-36) can be identified with relatively high reliability using the system [9]. In addition, it has been possible to use our system to reliably score behavioral events without labor-and time-intensive (and potentially biased) human scoring; for example, our system has been used to automatically detect directional reversals with high reliability in a touch avoidance assay [10]. Other specific postures such as coils can also be detected with high (>90%) reliability (Z. Feng, unpublished data).

With appropriate controls, a standardized phenotyping system also makes it possible to compare behavioral data collected by different researchers in different labs with greater precision than is possible using qualitative observer-driven approaches. In particular, a computerized system makes it possible to comprehensively assay multiple aspects of behavior simultaneously, yielding a complex phenotypic signature that can be used for bioinformatic studies [11]. In the future, we hope to use the tools described here to generate a comprehensive C. elegans phenotypic database that could be used to explore the clustering and relative similarities of mutant phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Hardware list

Algorithms for feature measurements

Codes

File list

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (to W.R.S. and P.W.S.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (P.W.S.). Zhaoyang Feng is a postdoctoral fellow of the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund/La Jolla Interfaces in Science interdisciplinary training program. The authors thank Anthony Kempf for critical discussion.

ZF and CJC jointly wrote the software and developed the system described here. JHW developed an early version of the system and designed the hardware configuration. PWS and WRS jointly conceived of this project, and participated in its design and coordination. WRS drafted the manuscript, CJC drafted the supplemental guide to the algorithms, and ZF drafted the supplemental hardware list. All authors read and approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Zhaoyang Feng, Email: zhaoyang@UCSD.Edu.

Christopher J Cronin, Email: cjc@caltech.edu.

John H Wittig, Jr, Email: john_wittig@yahoo.com.

Paul W Sternberg, Email: pws@caltech.edu.

William R Schafer, Email: wschafer@ucsd.edu.

References

- Rankin CH. From gene to identified neuron to behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:622–630. doi: 10.1038/nrg864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin ER, Ranganathan R, Horvitz HR. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron. 2000;26:619–631. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81199-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie PJ, Mellem JE, Hills T, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. The C. elegans glutamate receptor subunit NMR-1 Is required for slow NMDA-Activated currents that regulate reversal frequency during locomotion. Neuron. 2001;31:617–630. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardaker LA, Singer E, Kerr R, Zhou GT, Schafer WR. Serotonin modulates locomotory behavior and coordinates egg-laying and movement in Caenorhabditis elegans . J Neurobiol. 2001;49:303–313. doi: 10.1002/neu.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans . Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. Male phenotypes and mating efficiency in Caenorhabditis elegans . Genetics. 1983;103:43–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/103.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner L, Zhou GT, Schafer RW, Schafer WR. Control of behavioral states by serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans . Neuron. 1998;21:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce-Shimomura JT, Morse TM, Lockery SR. The fundamental role of pirouettes in Caenorhabditis elegans chemotaxis. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9557–9569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09557.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W, Cosman P, Berry CC, Feng Z, Schafer WR. Automatic tracking, feature extraction and classification of C. elegans phenotypes. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanyal S, Wintle RF, Kindt KS, Nuttley WM, Arvan R, Fitzmaurice P, Bigras E, Merz D, Hebert TE, van der Kooy D, Schafer WR, Culotti JG, van Tol HHM. Dopamine modulates the plasticity of mechanosensory responses in C. elegans. EMBO Journal. 2004;23:473–482. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W, Cosman P, Baek JH, Berry CC, Schafer WR. Quantitative classification and natural clustering of C. elegans behavioral phenotypes. Genetics. 2003;165:1117–1123. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hardware list

Algorithms for feature measurements

Codes

File list