Abstract

Objective

To review low-voltage versus high-voltage electrical burn complications in adults, and to identify novel areas that are not recognized to improve outcomes.

Methods

An extensive literature search on electrical burn injuries was performed using OVID Medline, PubMed and EMBASE databases from 1946–2015. Studies relating to outcomes of electrical injury in the adult population (≥18 years of age) were included in the study.

Results

Forty-one single-institution publications with a total of 5485 electrical injury patients were identified and included in the present study. 18.0% of these patients were low-voltage injuries (LVI), 38.3% high-voltage injuries (HVI) and 43.7% with voltage not otherwise specified (NOS). Forty-four percent of studies did not characterize outcomes according to low versus high-voltage injuries. Reported outcomes include surgical, medical, post-traumatic, and other (long-term/psychological/rehabilitative), all of which report greater incidence rates in HVI compared to LVI. Only two studies report on psychological outcomes such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Mortality from electrical injuries are 2.6% in LVI, 5.2% in HVI and 3.7% in NOS. Coroner’s reports reveal a ratio of 2.4:1 for deaths caused by low-voltage injury compared to high voltage-injury.

Conclusions

High-voltage injuries lead to greater morbidity and mortality than low-voltage injuries. However, the results of the coroner’s reports suggest that immediate mortality from low-voltage injury may be underestimated. Furthermore, based on the data of this analysis we conclude that the majority of studies report electrical injury outcomes, however, the majority of them do not analyze complications by low versus high voltage and often lack long-term psychological and rehabilitation outcomes post-electrical injury indicating that a variety of central aspects are not being evaluated or assessed.

Keywords: Electrical injury, electrical burn, low-voltage, high-voltage

Introduction

Electrical injuries are an uncommon but potentially devastating, and constitute approximately 0.04–5% of admissions to burn units in developed countries, and up to 27% in developing countries (1, 2). Classification of electrical injuries are typically divided into low-voltage (<1000 volts) and high-voltage (>1000 volts), as well as by whether electrical current flows directly through the body versus a thermal injury caused by electrical flash. Electrical injuries in the adult population primarily affect males, are most often work-related, and are the 4th leading cause of traumatic work-related death (3). Both morbidity and mortality in electrical injuries are relatively high, and have physical as well as psychological short-term and long-term sequelae (4,5,6). This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of reported electrical injury outcomes worldwide, in an attempt to gain a better understanding of the distribution of morbidity and mortality between low-voltage and high-voltage electrical injuries. Additionally we wanted to identify areas in electrically injured patients that are not identified nor studies but affect outcomes.

Methods

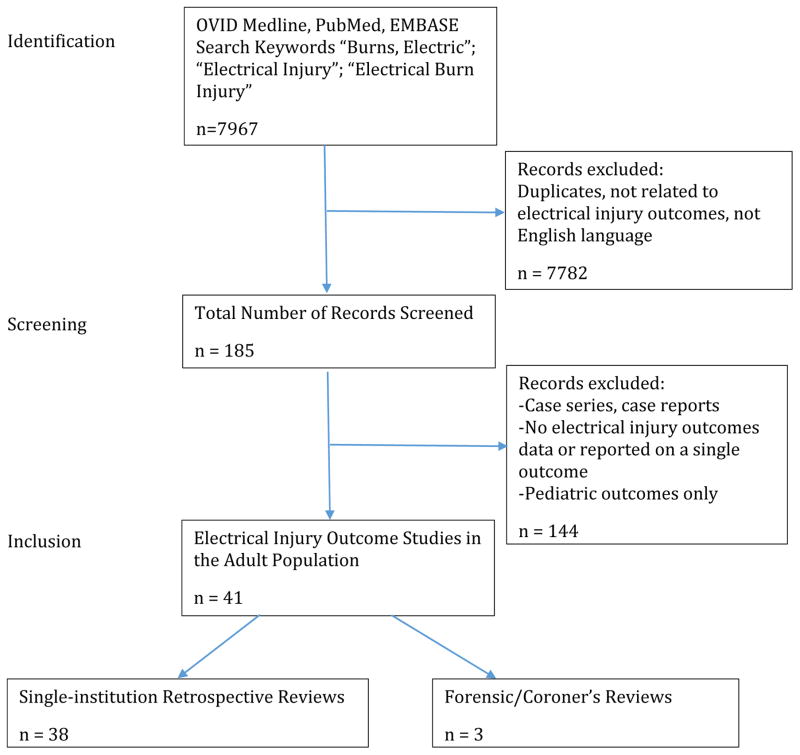

An extensive literature search on electrical burn injuries was performed using OVID Medline, PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane databases from 1946–2015 September. An initial search was performed using keywords “Burns, Electric”, “Electrical Injury” and “Electrical Burn Injury”, and an extended search of related articles and referenced articles identified additional studies (see Figure 1). Studies relating to outcomes of electrical injury in the adult population were included in the study that reported on more than one outcome. Studies relating to lightning electrical injuries alone were excluded. Case reports and case series were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Identification, screening and inclusion of articles from initial database search results.

Electrical injuries were categorized according to low-voltage (LV - reported as low-voltage < 1000 volts), high-voltage (HV - reported as high-voltage > 1000 volts), or voltage not otherwise specified (NOS). Each category required more than one study reporting the outcome to be included in our results to eliminate unrepresentative samples. Statistical analysis was performed using means and standard deviations. When comparing low-voltage versus high-voltage electrical injury outcomes reported by study, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 41 publications (1, 2, 4–42) were included in this study, 38 of which were single-institution adult population reviews, and 3 of which were forensic or coroner’s reviews.

Single-Institution Retrospective Reviews

All of the thirty-eight retrospective reviews were single-institution reviews of burn admissions and outcomes of electrical burn injury in adults, published between the years of 1969 and 2015. Most of the studies were published from an institution in North America (42.1%) or Asia (34.2%), with the remainder from Europe (18.4%), Australia (2.6%) or South America (2.6%).

There was a total of 5485 electrical injuries reported in these 38 studies, with the majority number of outcomes reported in patient’s whose electrical injury voltage was not specified (43.7%). There was a greater number of reported outcomes in high-voltage electrical injury (38.3%) vs. low-voltage electrical injury (18.0%) – see Table 1.

Table 1.

Total number of electrical injuries categorized by voltage specification.

| Total # of electrical injuries | |

|---|---|

| n (% of Total) | |

| Total Studies that Identified Low-Voltage, High-Voltage and Not Otherwise Specified Electrical Injuries | |

| LV | 986 (18.0%) |

| HV | 2100 (38.3%) |

| NOS | 2399 (43.7%) |

| Total | 5485 (100%) |

Low vs. High Voltage Admissions and Morbidity Data

On average, electrical burn injuries comprised 4.2% of all burns admissions to institutions worldwide. When comparing the total number of high-voltage electrical injuries (2100), low-voltage electrical injuries (986) and voltage not otherwise specified (NOS) (2399) reported, the following admissions data was extrapolated (see Table 2). The average age of all electrical injury patients was 30.9 years, with 93.9% males and 6.1% females. Seventy-five percent of injuries occurred in the workplace. The average TBSA on admission was 14.0%.

Table 2.

Admissions data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported.

| Low-Voltage | High-Voltage | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 27.8 | 38.5 | 30.1 |

|

| |||

| Percentage Male (%) | 85.8 | 93.1 | 94.9 |

| Percentage Female (%) | 14.2 | 6.9 | 5.1 |

|

| |||

| Injuries at Work (%) | 77.0 | 82.0 | 70.2 |

|

| |||

| Average TBSA (%) | 10.6 | 17.6 | 13.5 |

Outcomes data for morbidities include surgical, medical, trauma-related, and other (long-term/psychological/rehabilitative). See Table 3, 4, 5 and 6 for comparison of these outcomes for low-voltage vs. high-voltage electrical injuries. ECG changes reported were mostly arrhythmias, ST changes (non-specific or T wave inversions), atrial/ventricular atopic beats, alterations in rhythm or rate, and atrial or ventricular fibrillation. Cardiac complications were seldom reported, but when reported consisted of cardiopulmonary arrest (n=48), acute myocardial infarctions (n=5), and pericarditis (n=5), and were in the categories of either high-voltage or voltage not otherwise specified. Elevated CK values were only reported in two of the studies.

Table 3.

Surgical outcomes data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported (ntotal).

| Low-Voltage | High- Voltage | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified | p-value (LV vs. HV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical intervention, % (ntotal)† | 54.1 (652) | 79.6 (608) | 66.1 (587) | 0.004* |

| Fasciotomy/Escharotomy, % (ntotal) † | 4.8 (395) | 27.0 (1019) | 15.7 (922) | 0.2 |

| Amputation, % (ntotal) † | 7.3 (640) | 30.2 (1898) | 27.2 (1501) | 0.02* |

| Compartment Syndrome, % (ntotal) † | - | 15.0 (120) | - | - |

| Reconstructive Flap, % (ntotal) † | - | 114.8 (684) | 12.5 (585) | - |

Statistically significant with p < 0.05

Percentage of number of total surgical excisions/fasciotomies/amputations/flaps (can be multiple per patient) over total number of electrical injury admissions in that category (ntotal).

Table 4.

Medical outcomes data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported (ntotal).

| Low-Voltage | High-Voltage | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified | p-value (LV vs. HV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Length of Stay, days (ntotal | 10.9 (600) | 31.2 (1717) | 19.8 (1898) | 0.002* |

| ECG changes, %(ntotal) | - | 20.0 (315) | 14.6 (941) | - |

| Myoglobinuria, %(ntotal) | - | 38.9 (476) | 27.3 (362) | - |

| Renal dysfunction, % (ntotal) | 0.0 (108) | 13.9 (1098) | 4.2 (873) | 0.4 |

| Infection (non-specific), % (ntotal) | - | 15.0 (832) | 25.5 (553) | - |

Statistically significant with p < 0.05

Table 5.

Trauma-related outcomes data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported (ntotal).

| Low-Voltage | High-Voltage | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of Consciousness, % (ntotal) | - | 36.8 (456) | 22.2 (522) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury, % (ntotal) | - | 5.1 (391) | 2.7 (442) |

| Associated Fracture, % (ntotal) | - | 11.8 (532) | 7.9 (544) |

| Traumatic Intra-Abdominal Injury, % (ntotal) | - | 2.0 (353) | 1.6 (372) |

| Cerebral dysfunction*, % (ntotal) | - | 1.3 (689) | 8.5 (247) |

Cerebral dysfunction includes seizures, severe cerebral edema, intracranial hemorrhage, and persistent vegetative state

Table 6.

Other outcomes data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported.

| Low-Voltage | High-Voltage | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathy, % (ntotal) * | - | 28.0 (193) | 17.0 (442) |

| Cataracts, % (ntotal) | - | 1.0 (863) | 1.9 (855) |

| Permanent Disability, % (ntotal) ** | - | - | 34.5 (493) |

| PTSD, % (ntotal) | - | - | 5.6 (430) |

Neuropathies include persistent dysesthesias and spinal cord injuries; specific peripheral neuropathies reported include ulnar, medial, radial and common peroneal neuropathies.

Reported as permanent disability to some degree.

Low vs High Voltage Mortality Data

An overall mortality rate for electrical injuries was reported at 4.1% (see Table 7 for data comparison by voltage). The most common causes of death were high TBSA from 50% to over 90%, multi-system organ failure, septicemia, pneumonia and renal failure.

Table 7.

Mortality data by low-voltage, high-voltage and voltage not otherwise specified by total numbers reported.

| Low-Voltage (ntotal) | High-Voltage (ntotal) | Voltage Not Otherwise Specified (ntotal) | p-value (LV vs. HV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality (%) | 2.6 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 0.2 |

| Mortality (n) | 23 | 92 | 71 | |

| Total number electrical burns* (ntotal) | 887 | 1755 | 1944 | |

| Cause of mortality reported (n, %) | 0 (0%) | 26 (28%) | 51 (72%) | |

| Reported Causes of Mortality* | ||||

| TBSA > 50%, n (%) | - | 12 (48%) | 10 (20%) | |

| Multi-organ failure/ Septicemia, n (%) | - | 11 (44%) | 7 (14%) | |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | - | 0 (0%) | 8 (15%) | |

| ARDS, n (%) | - | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Renal Failure/ATN, n (%) | - | 0 (0%) | 14 (27%) | |

| Myocardial infarction/Cardiopulmonary arrest, n (%) | - | 1 (4%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | - | 0 (0%) | 9 (18%) | |

| Hepatic failure, n (%) | - | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

Of studies that reported mortality rates.

Forensic Reviews

A total of 1165 autopsies results were reported from the three forensic reviews. Of these, 735 (63.0%) were due to low-voltage electrical injury, 306 (26.3%) were due to high-voltage electrical injury, 31% of which were lightning injuries, and the remainder 124 deaths (10.6%) did not specify voltage. The percentage of males was 98.8% and females was 1.2%. Of the studies included, the place of injury was reported in 20% of the total population, with the percentage of deaths occurring at work being 51.3% compared to 48.7%. One study reported deaths as accidental versus other, and reported 69% accidental deaths, 29% suicide and 2% homicide (25).

Discussions

Electrical burn injuries comprise of less than 5% of all admissions to burn centers worldwide, however have significant morbidity and mortality associated with them. Our study revealed that high-voltage electrical injuries generally have significantly greater morbidity in terms of greater number of surgical procedures required, higher rates of medical complications, lead to multiple post-traumatic injuries due to falls, and may result in more long-term psychological and rehabilitative problems. In addition to the overall rates of injuries revealed in this study, we have discovered that many of these single-institution retrospective reviews do not separate outcomes by low-voltage versus high-voltage. An even greater proportion of studies do not assess psychological outcomes such as rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or rehabilitative outcomes associated with these highly morbid injuries involving the musculoskeletal and neurological system.

In addition to several case reports of PTSD following electrical injury (43–45), several studies using neuropsychological testing following electrical injuries have revealed that PTSD is a significant problem, which can lead to poor cognitive performance and decreased ability to return to work (46, 47). The no-let-go phenomenon associated with low-voltage electrical injury also results in higher rates of PTSD and major depression (48), therefore it would be important to determine if there are any differences in rates of psychiatric disorders in low-voltage vs. high-voltage injuries.

Mortality rates for high-voltage electrical injuries are higher than low-voltage injuries for patients presenting to hospital, however, interestingly mortality rates according to coroner’s reports are much higher in the low-voltage injury population compared to high-voltage injury, with a ratio of 2.4:1. This may represent a higher proportion of immediate deaths at the scene related to low-voltage injury. Approximately one third of high-voltage mortalities were a result of lightning strike, which often results in immediate death and whose morbidity was not included in this study.

There are several limitations to this study. Several of the reported outcomes were only reported by one or two studies, which may skew the results. In addition, many studies look at single outcomes such as cardiac complications or increases in certain laboratory values, which were not included in this review.

With these limitations in mind, this review has provided a compilation of outcomes from dozens of single-institution burn centers worldwide, analyzed by low-voltage injuries, high-voltage injuries and electrical injuries with voltage not otherwise specified. This review has revealed a significant morbidity and mortality with respect to physical, cognitive, psychiatric and rehabilitative sequelae. With further assessment and knowledge of long-term outcomes of electrical injury, we can focus on clinical identification and proper management of the complications faced by electrical injury survivors.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This study was supported by -Canadian Institutes of Health Research # 123336. CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund: Project # 25407 NIH RO1 GM087285-01; Hydro One and Toronto Hydro.

References

- 1.Hunt JL, Sato RM, Baxter CR. Acute electric burns. Arch Surg. 1980;115:434–438. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1980.01380040062011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal S, Maitz P, Kennedy P. Electrical flash burns due to switchboard explosions in New South Wales--a 9-year experience. Burns. 2011;37(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koumbourlis AC. Electrical injuries. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S424–S430. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF, Kowalske K, et al. Electrical injuries: a 20-year review. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:479–484. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000144536.22284.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vierhapper MF, Lumenta DB, Beck H, Keck M, Kamolz LP, Frey M. Electrical injury: a long-term analysis with review of regional differences. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(1):43–46. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181f3e60f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saracoglu A, Kuzucuoglu T, Yakupoglu S, et al. Prognostic factors in electrical burns: a review of 101 patients. Burns. 2014;40(4):702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiVincenti FC, Moncrief JA, Pruitt BA. Electrical injuries: a review of 65 cases. J Trauma. 1969;9:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler ED, Gant TD. Electrical injuries, with special reference to the upper extremities. Am J Surg. 1977;134:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinby WC, Burke JF, Trelstad RL, Caulfield J. The use of microscopy as a guide to primary excision of high tension electrical burns. J Trauma. 1978;18:423–429. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197806000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson C, Wood M. High Voltage Electrical Injury. Am J Surg. 1978;136:693–696. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luce EA, Gottlieb SE. “True” high-tension electrical injuries. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;12:321–326. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parshley PF, Kilgore J, Pulito JF, Smiley PW, Miller SH. Aggressive approach to the extremity damaged by electric current. Am J Surg. 1985;150:78–82. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(85)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haberal M, Oner Z, Gulay H, Bayraktar U, Bilgin N. Severe electrical injury. Burns. 1989;15(1):60–63. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(89)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandra NC, Siu CO, Munster AM. Clinical predictors of myocardial damage after high voltage electrical injury. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:293–297. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gang RK, Bajec J. Electrical burns in Kuwait: a review and analysis of 64 cases. Burns. 1992;18(6):497–499. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(92)90184-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancio LC, Jimenez-Reyna JF, Barillo DJ, Walker SC, McManus AT, Vaughan GM. One Hundred Ninety-Five Cases of High-Voltage Electric Injury. J Burn Care Res. 2005;26(4):331–340. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000169893.25351.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussmann J, Kucan JO, Russell RC, et al. Electrical injuries, morbidity, outcome and treatment rationale. Burns. 1995;21:530–535. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00037-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann R, Gibran N, Engrav L, Heimbach D. Is immediate decompression of high voltage electrical injuries to the upper extremity always necessary. J Trauma. 1996;40(4):584–589. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrowsmith J, Usgaocar RP, Dickson WA. Electrical injury and frequency of cardiac complications. Burns. 1997;23:676–678. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreiro I, Melendez J, Regalado J, Bejar FJ, Gabilondo FJ. Factors infuencing the sequelae of high tension electrical injuries. Burns. 1998;24:649–653. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yowler CJ, Mozingo DW, Ryan JB, Pruitt BA. Factors contributing to delayed extremity amputation in burn patients. J Trauma. 1998;45:522–526. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199809000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Sanchez V, Gomez Morell P. Electric burns: high- and low-tension injuries. Burns. 1999;25(4):357–360. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tredget EE, Shankowsky HA, Tilley WA. Electrical injuries in Canadian burn care. Identification of unsolved problems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;888:75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey B, Forget S, Gaudreault P. Prevalence of potential risk factors in victims of electrocution. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;123(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00525-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wick R, Gilbert JD, Simpson E, Byard RW. Fatal electrocution in adults--a 30-year study. Med Sci Law. 2006;46(2):166–172. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.46.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dega S, Gnaneswar SG, Rao PR, Ramani P, Krishna DM. Electrical burn injuries. Some unusual clinical situations and management. Burns. 2007;33(5):653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammadi AA, Amini M, Mehrabani D, Kiani Z, Seddigh A. A survey on 30 months electrical burns in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Burn Hospital. Burns. 2008;34(1):111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeong EK, Huang HF. Persistent vegetative state in electrical injuries: a 10-year review. Burns. 2008;34(4):539–542. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dokov W. Assessment of risk factors for death in electrical injury. Burns. 2009;35:114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handschin AE, Vetter S, Jung FJ, Guggenheim M, Kunzi W, Giovanoli P. A case-matched controlled study on high-voltage electrical injuries vs thermal burns. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(3):400–407. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181a289a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luz DP, Millan LS, Alessi MS, et al. Electrical burns: a retrospective analysis across a 5-year period. Burns. 2009;35(7):1015–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsueh YY, Chen CL, Pan SC. Analysis of factors influencing limb amputation in high-voltage electrically injured patients. Burns. 2011;37(4):673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lumenta DB, Vierhapper MF, Kamolz LP, Keck M, Frey M. Train surfing and other high voltage trauma: differences in injury-related mechanisms and operative outcomes after fasciotomy, amputation and soft-tissue coverage. Burns. 2011;37(8):1427–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fish JS, Theman K, Gomez M. Diagnosis of long-term sequelae after low-voltage electrical injury. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(2):199–205. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182331e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matt SE, Shupp JW, Carter EA, Shaw JD, Jordan MH. Comparing a single institution's experience with electrical injuries to the data recorded in the National Burn Repository. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(5):606–611. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318241b13d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun CF, Lu XX, Li YJ, Li WZ, Jian L, Li J, Feng J, Chen SZ, Wu F, Li XY. Epidemiological studies of electrical injuries in Shaanxi Province of China: A retrospective report of 383 cases. Burns. 2012;38:568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bae EJ, Hong IH, Park SP, Kim HK, Lee KW, Han JR. Overview of ocular complications in patients with electrical burns: an analysis of 102 cases across a 7-year period. Burns. 2013;39(7):1380–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghavami Y, Mobayen MR, Vaghardoost R. Electrical burn injury: a five-year survey of 682 patients. Trauma Mon. 2014;19(4):e18748. doi: 10.5812/traumamon.18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipový B, Kaloudová Y, Ríhová H, Chaloupková Z, Kempný T, Suchanek I, Brychta P. High voltage electrical injury: an 11-year single center epidemiological study. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2014;27(2):82–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piotrowski A, Fillet AM, Perez P, et al. Outcome of occupational electrical injuries among French electric company workers: a retrospective report of 311 cases, 1996–2005. Burns. 2014;40(3):480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aghakhani K, Heidari M, Tabatabaee SM, Abdolkarimi L. Effect of current pathway on mortality and morbidity in electrical burn patients. Burns. 2015 Feb;41(1):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lunawat A, Datey SM, Vishwani A, Vashistha R, Singh V, Maheshwari T. Evaluation of quantum of disability as sequelae of electric burn injuries. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(3):PC01–PC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12243.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Premalatha GD. Post traumatic stress disorder following an electric shock. Med J Malaysia. 1994;49(3):292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laforce R, Jr, Gibson B, Morehouse R, Bailey PA, MacLaren VV. Neuropsychiatric profile of a case of post traumatic stress disorder following an electric shock. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(4):524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silva JA, Leong GB, Ferrari MM. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Burn Patients. Southern Med J. 1991;84(4):530–531. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199104000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaergaard A. Late sequelae following electrical accidents [in Danish] Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171(12):993–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grigorovich A, Gomez M, Leach L, Fish J. Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression on neuropsychological functioning in electrical injury survivors. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34(6):659–65. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31827e5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelley KM, Tkachenko TA, Pliskin NH, Fink JW, Lee RC. Life after electrical injury. Risk factors for psychiatric sequelae. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;888:356–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]