Abstract

The introduction of antiretroviral drugs (ARVd) changed the prognosis of HIV infection from a deadly disease to a chronic disease. However, even with undetectable viral loads, patients still develop a wide range of pathologies, including cerebrovascular complications and stroke. It is hypothesized that toxic side effects of ARVd may contribute to these effects. To address this notion, we evaluated the impact of several non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI; Efavirenz, Etravirine, Rilpivirine and Nevirapine) on the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, and their impact on severity of stroke. Among studied drugs, Efavirenz, but not other NNRTIs, altered claudin-5 expression, increased endothelial permeability, and disrupted the blood-brain barrier integrity. Importantly, Efavirenz exposure increased the severity of stroke in a model of middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Taken together, these results indicate that selected ARVd can exacerbate HIV-associated cerebrovascular pathology. Therefore, careful consideration should be taken when choosing an anti-retroviral therapy regimen.

The introduction of anti-retroviral drugs (ARVd) changed the prognostic of HIV infection from a terminal to a chronic disease. Patients can lead normal lives and control the infection by adhering to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)1,2. Nevertheless, these patients will likely be under treatment for the rest of their lives, meaning that they will be continually exposed to ARVd. Given the length of exposure, infected patients are at higher risk of developing co-morbidities, such as cardiovascular, metabolic and neurological disease3,4,5,6,7. While some of these disorders can be attributed to HIV infection and the ensuing persistent state of inflammation, growing evidence indicates that ARVd toxicity could be at least partially involved in the development of these pathologies. Several side effects, such as lactic acidosis, lipodystrophy, hyperbilirubinemia, diarrhea, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy, neuropsychiatric disorders and hypersensitivity, have been linked to the use of ARVd8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. HIV protease inhibitors have been associated with proteasome disruption, liver injury, and gut barrier dysfunction19. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) may be responsible for induction of inflammation20, neurotoxicity, and rashes21. While the direct cause of these adverse reactions can be multifactorial, certain NNRTIs, especially Efavirenz, can play an important role given the indications that they can disrupt nitric oxide production, mitochondrial function, ER stress and autophagy22,23,24,25.

The long term survival of HIV infected patients makes them more susceptible to the development of cardiovascular diseases26. Several epidemiologic studies denoted that these individuals are younger and present a higher incidence of vasculopathies, cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases than non-infected patients27,28,29,30. HIV-positive patients who develop stroke often present a different profile than the general population, exhibiting less predisposing symptoms, such as hypertension31. Multiple factors linked to the HIV infection can contribute to this increased susceptibility, including chronic vascular inflammation, opportunistic infections, endocarditis, cachexia, coagulation abnormalities, and dyslipidemia. Furthermore, HIV and its proteins can interact directly with the endothelium and contribute to increased incidence of atherosclerosis, a major contributing factor of cardiovascular disease32,33, which can further be exacerbated by antiretroviral treatment. Epidemiological studies demonstrated that while endothelial dysfunction is reduced following HAART initiation, long term exposure to ARVd leads to the development of vasculopathy, especially with the usage of certain protease inhibitors34,35. These conditions could arise from chronic induction of ER stress36,37, an increase in local inflammation38, or apoptosis activation39.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) plays a central role in maintaining the homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS). The BBB protects the brain from toxins, pathogens, and other potential harmful components that can be present in the blood40,41,42,43. The BBB is composed of the neurovascular units in which neurons interact with three major cell types: endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes. The brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) are linked together by an assembly of tight junction (TJ) proteins that restrict the passage of molecules at the paracellular space. The main component of these structures are claudins (primarily claudin-5), which are transmembrane proteins that connect the neighboring endothelial cells. These proteins are linked to the cytoskeleton by adaptor proteins, such as zona occludens-1, 2, 3 and cingulin. In addition, several other molecules also play a role in TJ assembly, such as occludin, junctional adhesion molecules, and adherens junction proteins40,44. The regulation of TJs is influenced by the signaling factors originating from BMEC, but also influenced by pericytes and astrocytes40,45,46. Dysfunction of the BBB and the associated increase in BBB permeability is linked to the pathology of several acute and chronic CNS diseases. An uncontrolled trafficking of immune cells to the CNS can lead to inflammation, neuronal loss, and the entry of pathogens, resulting in infections. The loss of control on the flow of molecules in or out of the CNS can contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, or stroke47. In the context of the present study, it is important that disrupted BBB can increase the extent of tissue damage and mortality in stroke48,49,50.

Several publications reported that ER stress induction is linked to endothelial dysfunction and can lead to an increased vascular permeability in various disease models51,52,53,54,55,56. We previously demonstrated that exposure of brain endothelial cells to Efavirenz induces ER stress and disrupts autophagy25. The present study aims to identify the impact of NNRTI-induced toxicity on endothelial functions, such as disruption the barrier integrity and the severity of stroke. Our results demonstrate that of the several NNRTIs tested, only Efavirenz affected endothelial integrity via reduction in claudin-5 expression, and alterations in its phosphorylation. In addition, treatment with Efavirenz resulted in an increase in BBB permeability and enhanced tissue injury in stroke.

Results

Exposure to Efavirenz, but not to other NNRTIs, leads to an increase in endothelial permeability

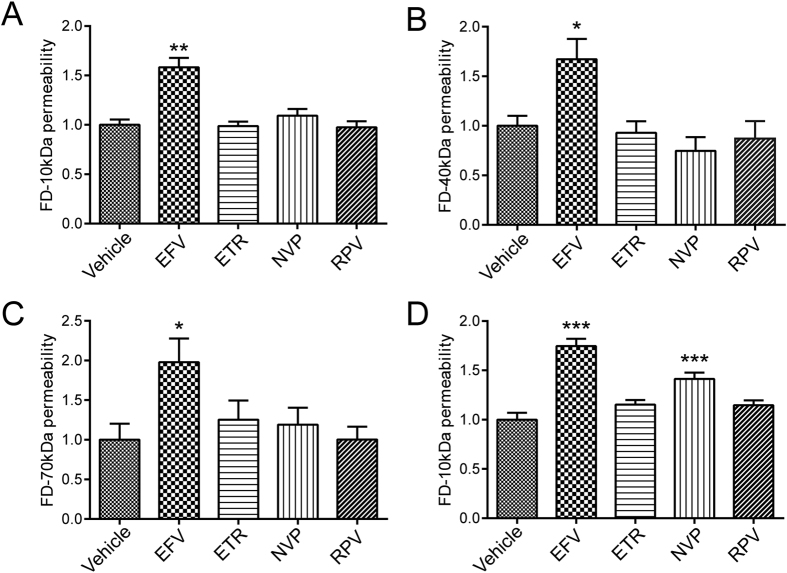

To evaluate the impact of NNRTI on endothelial permeability, human cerebral microvascular cells (hCMEC) were grown to confluence on Transwell inserts. After the formation of monolayers, the cells were exposed to the indicated conditions for 48 h. Then, media in the apical compartment of the Transwell system was replaced with medium containing fluorescently-tagged dextran. After 90 min incubation, fluorescence intensity in the basal compartment was read using a plate reader. Among studied NNRTIs, exposure to Efavirenz resulted in a significant increase in permeability of hCMEC monolayers for all molecular sizes of dextran tested (Fig. 1A–C). Exposure to the other NNRTIs did not affect the transfer of fluorescent markers across the endothelial monolayer. These results were largely confirmed in cultures of human primary brain endothelial cells (Fig. 1D). However, exposure to Nevirapine slightly increased permeability across the monolayers of primary brain endothelial cells. Such results appear to be consistent with different susceptibly of primary cells compared to a cell line.

Figure 1. Impact of NNRTIs on endothelial permeability.

hCMEC (A–C) and human primary brain endothelial cells (D), grown to confluence on Transwells, were incubated with vehicle (DMSO), Efavirenz (Efa), Etravirine (ETR), Nevirapine (NVP) or Rilpivirine (RPV) for 48 h. Culture media in the apical compartment of the Transwell system was replaced with medium containing fluorescently tagged dextran (FD) of 10 kDa (A and D), 40 kDa (B) or 70 kDa (C). Basolateral levels of FD were assayed 90 min post exposure. Data are mean ± SEM, expressed as fold increase over vehicle control; three independent experiments, each with n = 4; *p < 0.05 vs. Vehicle; **p < 0.01 vs. Vehicle; ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehicle.

Efavirenz, but not other NNRTIs, induces a specific reduction in claudin-5 levels

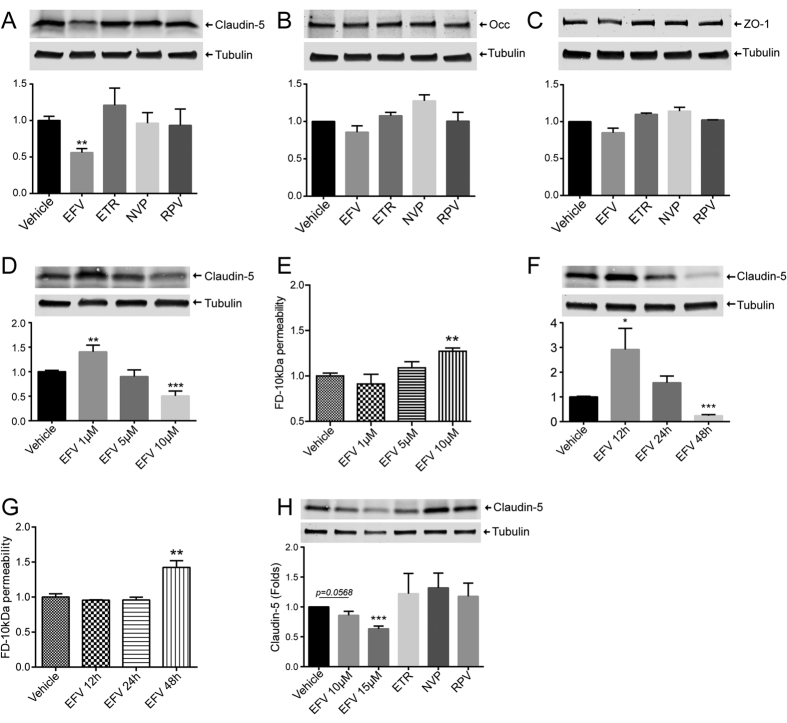

We next sought to identify the impact of NNRTI exposure on TJ protein levels, given their primordial role in maintaining endothelial barrier function. Cells were exposed to NNRTIs as in Fig. 1 and lysed using RIPA buffer. The expression levels of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1, three major TJ proteins, were analyzed by western blotting. A specific reduction in claudin-5 levels was observed in cells exposed to Efavirenz, but not to other NNRTIs (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, occludin and ZO-1 levels remained unaffected, independent of treatment (Fig. 2B and C, respectively). In order to evaluate dose response effects of Efavirenz, we exposed hCMEC to doses ranging from 1 μM to 10 μM. Efavirenz at 10 μM consistently lowered claudin-5 levels; however, treatment with 1 μM resulted in a significant increase in expression of this protein (Fig. 2D). No significant impact of Efavirenz on endothelial permeability was observed at doses lower than 10 μM (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Impact of NNRTIs on tight junction protein expression.

hCMEC (A–G) and human primary brain endothelial cells (H) were grown to confluence, followed by exposure to vehicle (DMSO), Efavirenz (Efa), Etravirine (ETR), Nevirapine (NVP) or Rilpivirine (RPV) for 48 h. Expression of claudin-5 (A,D,F,H), occludin (B), and ZO-1 (C) was assessed by western blotting. Dose-dependent effects of Efavirenz on claudin-5 levels (D,H) and endothelial permeability (E). Time-dependent impact of Efavirenz on claudin-5 levels (F) and endothelial permeability (G). Presented blots are cropped from the originals, full size blots available in Supplementary Fig. S1. Data are mean ± SEM, expressed as fold increase over vehicle control; three or four independent experiments, each with n = 4. *p < 0.05 vs. Vehicle; **p < 0.01 vs. Vehicle; ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehicle.

We also investigated time-dependent effects of Efavirenz exposure on claudin-5 expression and endothelial barrier function. A significant decrease in claudin-5 and endothelial barrier function was confirmed at 48 h of exposure (Fig. 2F and G, respectively). A 12 h treatment with Efavirenz increased claudin-5 levels (Fig. 2F) with no impact on permeability (Fig. 2G). No changes in these parameters were observed in cells exposed to Efavirenz for 24 h.

In human primary brain endothelial cells, exposure to Efavirenz, but not other NNRTIs, lead to a decrease in claudin-5 expression (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, all listed treatments did not impact either occludin or ZO-1 (data not shown), fully confirming the results from a cell line.

Overall, these results indicate that Efavirenz exposure results in an increase in monolayer permeability that correlates with a specific reduction in claudin-5 level. In addition, this effect is contingent on dose and exposure time.

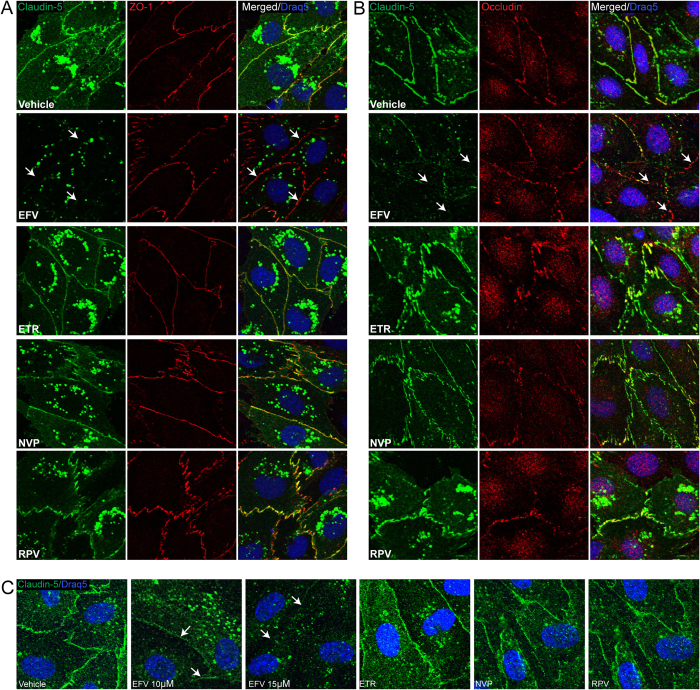

Disruption of intracellular localization of claudin-5 by Efavirenz

In addition to the expression level, cellular localization of TJ proteins is essential for their function. Therefore, we assessed the impact of NNRTIs on claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 immunoreactivity. hCMEC were grown to confluence on round coverslips coated with collagen, and exposed to vehicle or NNRTIs for 48 h. Afterward, cells were processed for immunofluorescence to assess cellular localization of TJ proteins. The nuclei were stained with DRAQ5. Using confocal microscopy, we detected a regular colocalization of claudin-5 with ZO-1, and claudin-5 with occludin in cells treated with DMSO, Etravirine, Nevirapine and Rilpivirine (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, in cells exposed to Efavirenz, this co-localization was absent due to both a severe reduction in the presence of claudin-5 from cell-cell junctions and a general reduction in expression level of this protein (Fig. 3A and B; arrows). Confirming these results, Efavirenz at 10 μM and 15 μM (but not other NNRTIs) decreased claudin-5 immunoreactivity and its presence at cell-cell junctions in primary human brain endothelial cells (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that in addition to a reduced expression, Efavirenz treatment affects subcellular localization of claudin-5 at TJs.

Figure 3. Treatment with Efavirenz, but not with other NNRTIs, decreases claudin-5 immunoreactivity and localization.

hCMEC were grown on coverslips to confluence, exposed to NNRTIs as in Fig. 1, and immunostained for claudin-5 (green), ZO-1 (red), or occludin (red). Draq5 (blue) visualizes nuclei. Left and middle columns in A and B are staining for specific tight junction proteins. The right column in (A) is colocalization of claudin-5 with ZO-1, and the right column in (B) is colocalization of claudin-5 with occludin. (C) Localization of claudin-5 in primary human brain endothelial cells. Arrows indicate discontinuous, absence of claudin-5 immunoreactivity and lack of ZO-1 or Occludin colocalization. EFV: Efavirenz; ETR: Etravirine; NVP: Nevirapine; RPV: Rilpivirine.

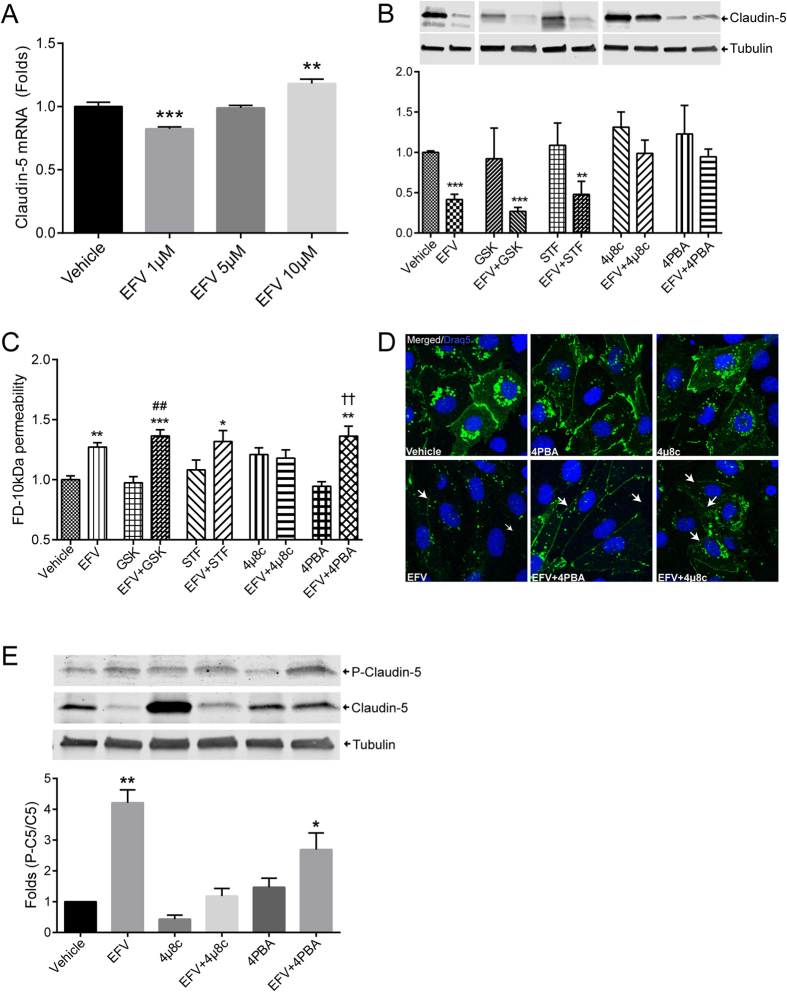

ER stress inhibition protects against Efavirenz-induced a decrease in claudin-5 expression, but not endothelial dysfunction

To identify the mechanisms of Efavirenz-induced claudin-5 downregulation, we first evaluate mRNA levels in cells exposed to increasing doses of this drug. While small changes in claudin-5 mRNA were detected (Fig. 4A), they did not correlate with the observed changes at the protein level. Specifically, a decrease in claudin-5 mRNA was observed in cells exposed to Efavirenz at 1 μM, i.e., the levels of the drug which increased claudin-5 protein level. In addition, 10 μM Efavirenz elevated claudin-5 mRNA (Fig. 4A); however, the same dose of Efavirenz consistently decreased claudin-5 protein expression (Figs 2 and 3). These results suggested a post-transcriptional mechanism of Efavirenz-induced alterations of claudin-5 expression.

Figure 4. Inhibition of ER stress restores Efavirenz-induced alterations of claudin-5 protein levels but not claudin-5 phosphorylation and disrupted endothelial permeability.

(A) Dose-depended effects of Efavirenz on claudin-5 mRNA levels as analyzed by real-time PCR. (B) Cells were pretreated with various ER stress inhibitors for 6 h before a 48 h exposure to 10 μM Efavirenz, followed by immunoblotting for claudin-5 protein expression. Tubulin was assessed as house-keeping reference. (C) Cells were treated as in (B) and endothelial permeability was evaluated using FD-10 kDa dye transfer as in Fig. 1. (D) Cells were pretreated with selected inhibitors of ER, followed by exposure to Efavirenz as in (C), and followed by staining for claudin-5 immunoreactivity (green). Draq5 (blue) visualizes nuclei. Arrows indicate discontinuous or absence of claudin-5 immunoreactivity. (E) Claudin-5 phosphorylation levels in cells exposed as in (D). Graphs represent ratio of phosphorylated claudin-5 (P-Claudin-5) compared to total claudin-5 levels. Presented blots are cropped from the originals, full size blots available in Supplementary Fig. S1. Data are mean ± SEM, expressed as fold increase over vehicle control; three or four independent experiments, each with n = 4. GSK: GSK2606414; STF: STF-083010; 4PBA: 4-Phenylbutyrate; EFV: Efavirenz. *p < 0.05 vs. Vehicle; **p < 0.01 vs. Vehicle; ***p < 0.001 vs. Vehicle; ##p < 0.01 vs. GSK; ††p < 0.01 vs. 4PBA.

We previously demonstrated that Efavirenz can induce ER stress25, which is a cellular response that can affect protein expression, via at least two ER sensors: PERK and IRE1α. Therefore, we evaluated whether induction of ER stress is involved in Efavirenz-induced alterations of claudin-5 expression. hCMEC were pretreated with several ER stress inhibitors (GSK2606414, PERK inhibitor; STF-083010, IRE1α inhibitor; 4 μ8c, IRE1α inhibitor; or 4-phenylbutyrate [4PBA] a broad inhibitor/chaperone) for 6 h, followed by treatment with Efavirenz for 48 h. As indicated in Fig. 4B, claudin-5 expression was restored to the control levels by 4 μ8c and 4PBA. However, treatment with 4 μ8c disrupted endothelial barrier function, and 4PBA was not effective in protecting against Efavirenz-induced disruption of endothelial permeability (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that ER stress inhibition can restore protein levels of claudin-5; however, this recovery does not fully extend to endothelial integrity. To explain this discrepancy, we observed that pretreatment with 4 μ8c or 4PBA failed to restore claudin-5 staining at cell junctions (Fig. 4D, arrows).

TJ protein levels are critical for TJ assembly and the barrier function, however an additional factor that may affect endothelial permeability is their phosphorylation. It has been demonstrated that claudin-5 phosphorylation results in an increase in BBB permeability, and that this modification can be in part mediated by Rho kinases57. Therefore, we analyzed phosphorylation levels of claudin-5 by western blotting in cells exposed to Efavirenz. The results indicated that Efavirenz resulted in a significant increase in claudin-5 phosphorylation, which was not restored by pretreatment with 4 μ8c or 4PBA (Fig. 4E). This indicated that while 4PBA prevents Efavirenz mediated reduction in claudin-5 proteins levels, phosphorylation levels remain high, the effect that correspond with disrupted barrier function.

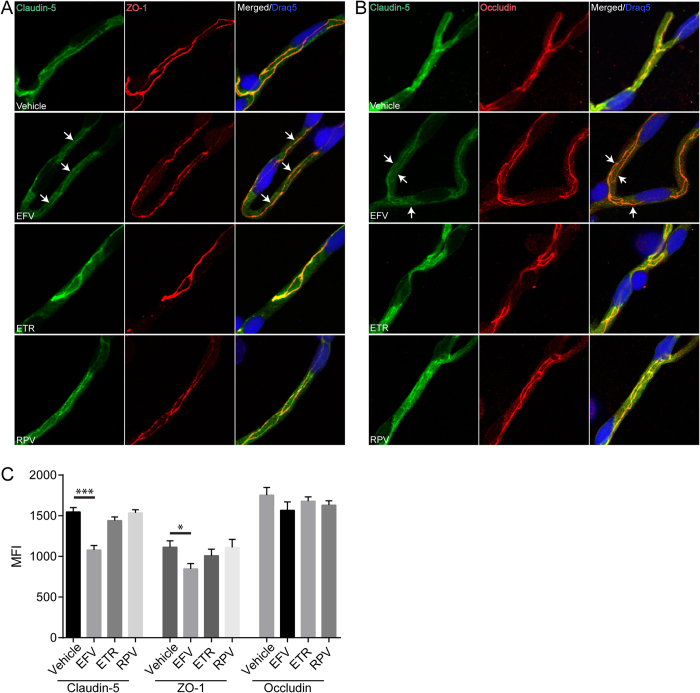

Treatment with Efavirenz, but not other NNRTIs, disrupts TJs in an animal model

Following the in vitro analyses, we next evaluated whether Efavirenz-induced alterations of TJ proteins occur in vivo in an animal model. Mice were gavaged with either vehicle, Efavirenz, Etravirine, or Rilpivirine for 30 days. Afterward, brains were harvested, the microvessels were isolated and analyzed by immunofluorescence for the expression and localization of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 (Fig. 5A and B). Among all NNRTIs used, only treatment with Efavirenz resulted in reduction of claudin-5 and ZO-1 immunoreactivity. Quantitative analysis of signal intensity by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) demonstrated a significant decrease in claudin-5 and to a lesser degree in ZO-1 in mice exposed to Efavirenz as (Fig. 5C). These changes were associated with disrupted claudin-5 colocalization with ZO-1 (Fig. 5A) and occludin (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that Efavirenz-induced TJ disruption occurs in vivo in a physiologically relevant treatment regimen.

Figure 5. Treatment with Efavirenz, but not other NNRTIs, affects claudin-5 immunoreactivity and localization in brain microvessels.

Mice were treated with various NNRTIs or vehicle for 30 days as described in the Materials and Methods. Claudin-5 (green), ZO-1 (red), and occludin (red) were analyzed by immunostaining in isolated brain microvessels. Nuclei were stained with Draq5 (blue). Left and middle columns in A and B are staining for specific tight junction proteins. The right column in (A) is colocalization of claudin-5 with ZO-1 and the right column in (B) is colocalization of claudin-5 with occludin. Arrows indicate discontinuous, absence of claudin-5 immunoreactivity and lack of ZO-1 or Occludin colocalization. (C) Quantification of mean fluorescence index (MFI) signal for tight junction proteins analyzed in isolated microvessels. Data obtained from 3 mice per group, 5–7 microvessels per mice. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. EFV: Efavirenz; ETR: Etravirine; RPV: Rilpivirine.

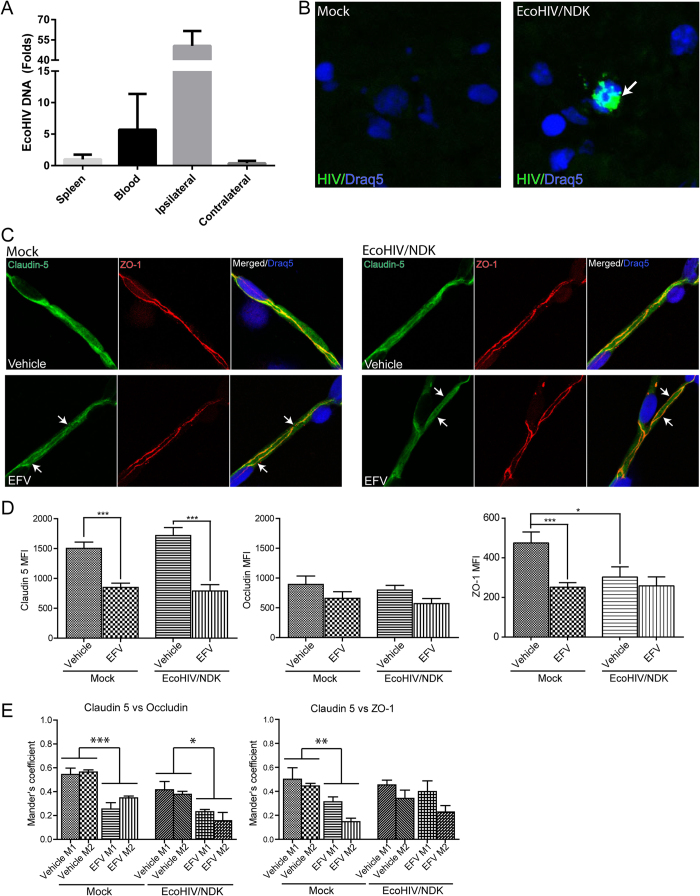

Efavirenz disrupts TJ integrity in EcoHIV/NDK-infected brains

Given that ARVd are typically used in HIV-infected individuals, we next compared the impact of Efavirenz on TJ integrity in mice infected with a chimeric HIV virus specifically adapted for mice, EcoHIV/NDK. To target the brain for infection, the virus was infused into the internal cerebral artery58, mimicking the initial stages of HIV brain infection in which the blood-borne virus enters the brain via the BBB. EcoHIV inoculation resulted in a preferential infection of the ipsilateral hemisphere, which corresponds to the site of virus infusion (Fig. 6A). The infection was confirmed by in situ PCR, which detected EcoHIV-infected cells mainly in the striatum (Fig. 6B). Seven days post infection, mice were treated for 30 days with Efavirenz or vehicle. Then, brain microvessels were isolated and immunostained for occludin (images not shown), claudin-5, and ZO-1 (Fig. 6C). The expression values of TJ proteins were calculated as MFI.

Figure 6. Tight junction protein expression and colocalization in EcoHIV/NDK-infected brains.

Mice were infected with the mouse adapted strain EcoHIV/NDK infused into the common carotid artery. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of HIV DNA content one week post infection. Bars represent fold changed compared to spleen HIV DNA content (n = 5). (B) In situ PCR analysis of HIV presence in brain sections of mock or EcoHIV/NDK infected mice. Positive HIV amplification is indicated in green (arrow). Nuclei are stained with Draq5 (blue). (C) Immunofluorescence of tight junction proteins in brain microvessels isolated from mock (left panel) or EcoHIV/NDK-infected (right panel) mice and treated with vehicle or Efavirenz (10 mg/kg for 30 days). Slides were immunostained for claudin-5 (green) and ZO-1 (red); Draq5 (blue) was used to stain nuclei. Arrows indicate discontinuous, absence of claudin-5 immunoreactivity and lack of ZO-1 colocalization. (D) Mean fluorescence index analysis of tight junction protein staining in isolated brain microvessels as in (C). Claudin-5, ZO-1, and occludin immunoreactivity was analyzed. (E) Analysis of colocalization of claudin-5 with ZO-1 or claudin-5 with occludin using the Mander’s coefficient. (C–E) Data obtained from 5 mice per groups, 5–9 microvessels per mice. Data are mean ± SEM. Analysis was performed using Image J and JACoP plugin. EFV: Efavirenz. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The infection with EcoHIV did not alter the MFI values for claudin-5 and occludin; however, ZO-1 levels were diminished as compared to mock infection (Fig. 6C and D). Treatment with Efavirenz markedly decreased claudin-5 levels in both animal groups, did not altered occludin levels, and diminished ZO-1 expression only in mock-infected mice. In addition, a reduction in colocalization of claudin-5 with occludin was identified using the Mander’s coefficient in both mock- and EcoHIV-infected mice (Fig. 6E). Colocalization of claudin-5 with ZO-1 was decreased only in mock-infected mice.

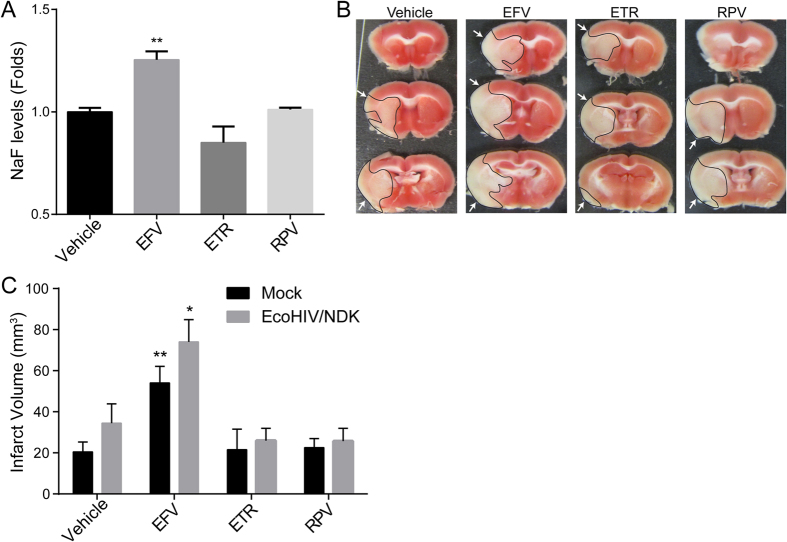

Efavirenz treatment increases BBB permeability and amplifies stroke severity in HIV-infected brains

Taking into consideration that TJs play a primordial role in maintaining BBB integrity, we evaluated the impact of NNRTIs on the BBB permeability. Animals were treated with NNRTIs as in Fig. 6, followed by intraperitoneal injection with sodium fluorescein (NaF), which was allowed to circulate for 20 min. Mice were then euthanized; blood was collected via cardiac puncture, and animals were perfused with saline. Brains were carefully harvested and processed for NaF quantitation. Treatment with Efavirenz, but not with other NNRTIs, induced a significant increase in NaF levels in the brains, indicating disrupted barrier function of the BBB (Fig. 7A). These results demonstrate that the disruption of TJ integrity caused by Efavirenz has functional implications on BBB permeability.

Figure 7. Efavirenz increases BBB permeability and stroke tissue injury.

(A) Quantification of BBB permeability. Mice were treated for 30 days with either vehicle or NNRTIs as described in the Material and Methods. Translocation of sodium fluorescein (NaF) from plasma into the brain parenchyma was used as the indicator of BBB integrity. Data are mean ± SEM, expressed as fold change compared to vehicle, n = 5 per group. To analyze infarct volume, mice were either mock or EcoHIV/NDK infected and treated as in (A). Brains were stained with TTC 24 h after a 60 min occlusion of the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). (B) Representative images of infarct areas in brain slices from NNRTI-treated mock-infected mice. Infarct areas are highlighted and indicated by arrows. (C) Quantification of total infarct volume from all animal groups. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 4–7 animals per group. *p < 0.05 vs. Vehicle; **p < 0.01 vs. Vehicle.

We next evaluated whether exposure to specific NNRTIs contributes to the development of stroke during HIV infection. HIV-infected patients are known to have a higher risk of stroke, which is often also more severe. Furthermore, stroke development and severity is exacerbated by a disrupted BBB50.

Mice were infected with EcoHIV and treated with NNRTIs as in Fig. 6, followed by induction of stroke by the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) for 60 min and reperfusion for 23 h59. Afterward, brains were harvested, sliced, and stained to analyze infarct volume. Among all tested NNRTIs, only Efavirenz treatment induced a significant increase in stroke severity when compared to vehicle. This phenomenon was observed both in mock and EcoHIV-infected mice (Fig. 7B and C). While there was a trend for a larger infarct volume in infected animals, the differences between the groups were below the threshold of statistical significance. These results indicate that while HIV is a potential contributor to stroke, Efavirenz has a highly significant impact on stroke severity, almost doubling infarct volume when compared to vehicle controls.

Discussion

The suppression of HIV replication using ARVd is essential in maintaining the health of seropositive patients. However, given that patients require antiretroviral therapy for the rest of their lives, drug toxicity is an important factor to take into consideration to prevent complications, and decrease the potential of exacerbating secondary diseases. Several publications demonstrated that selected ARVd used in the treatment of HIV have serious side effects which can affect patient health outcome. In addition, while HAART can suppress viral replication below detectable levels, there is a continuous presence of circulating viral proteins that alone can contribute to disease and lower the threshold of ARVd toxicity60.

While several categories of ARVds exist and are used in HIV-infected patients, we focused on toxicity of NNRTIs, selecting drugs from the first and second design generation that are currently in use in clinics. Even though Efavirenz was recently removed from the initial treatment option in the US, it is still part of the first NNRTI based regimen recommended by the WHO, and remains commonly used worldwide. Second generation NNRTIs have also been included in this study to evaluate cerebrovascular effects and safety of these drugs. We, and others, reported that Efavirenz induces ER stress and affects the autophagy pathway23,24,25, which are likely to affect other pathways and impact cell functions in biological systems. In the current study, we investigated the toxicity of Efavirenz, as well as Etravirine, Nevirapine, and Rilpivirine, by focusing on one of the primary roles of brain endothelial cells, namely the integrity of the BBB.

The structure of the BBB relies on the function of multiple cells, namely endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes. While conditions affecting any of those cells can compromise the integrity of this barrier, we focused our investigation on brain microvascular endothelial cells given their central role in the formation and regulation of the BBB. Our results demonstrate that at physiologically relevant concentrations, of all of the NNRTIs tested, only Efavirenz affected endothelial integrity, leading to an increase in permeability. While we observed a slight increase in permeability of primary brain endothelial cells exposed to Nevirapine, none of the other tests performed confirmed endothelial toxicity of this drug. The barrier function is highly reliant on the formation of TJs, composed especially claudin-5, ZO-1, and occludin, which were included in the present study. Claudin-5 was demonstrated to be an important contributor to BBB integrity61 and its upregulation correlates with a protective effect against CNS tissue injury62. Similar observations have been made for ZO-1 and occludin both in vitro and in vivo62,63,64,65. In our model system, exposure to Efavirenz selectively decreased the levels of claudin-5. These effects were dose- and time-dependent, and were observed both in vitro (in two different model systems) and in vivo. Efavirenz also had an impact on intracellular localization of this protein, with the prominent effect on removing claudin-5 from cell-cell junctions. In contrast, no changes in expression levels or localization were observed for occludin in our model systems. ZO-1 levels were not affected in vitro; however, they decreased upon Efavirenz administration in an animal model. This observation is important as it demonstrates that in vitro drug toxicity assays do not fully reproduce responses in more complex biological systems. Treatment with Efavirenz also disrupted the integrity of the BBB in vivo, which is consistent with the role of claudin-5 in maintaining the BBB barrier function66.

We next sought to identify the mechanisms of claudin-5 disruption. Given our previous observations that Efavirenz induced ER stress in brain endothelial cells, we investigated the role of this process in alterations of claudin-5 expression and localization. This line of investigation is consistent with the reports on the role of ER stress in vascular dysfunction in coronary disease67,68, diabetic retinopathy69 and, several other processes involving endothelium70,71. While the role of claudin-5 in maintaining vessel integrity is well established, limited data is available on the impact ER stress on integrity of claudin-5 and other TJ proteins51,72,73,74.

We demonstrated previously that the PERK and IRE1α pathways are involved in Efavirenz-induced ER stress. Based on these results, several inhibitors were employed in the present study to explore the link between ER stress, claudin-5, and disrupted endothelial permeability. We identified two inhibitors, namely 4 μ8c and 4PBA, which prevented Efavirenz-induced alterations of claudin-5 expression; however, they did not restore endothelial barrier function. Regarding 4 μ8c, given that it alone resulted in an increase in endothelial permeability, it is reasonable to assume that an off target effect could be at play. On the other hand, 4PBA restored the total levels of claudin-5 in Efavirenz-treated cells; however, immunostaining pattern exhibited a preserved diminished intensity and discontinuity at cell-cell junctions. In addition, 4PBA pretreatment did not restore Efavirenz-induced alterations of claudin-5 phosphorylation, a process that is influenced by Rho kinases and leads to a decrease in TJ tightness75,76. To support this notion, it has been shown that Efavirenz can increase cytoplasmic calcium levels, which has been linked to Rho kinase activation77. In addition, HIV-1 is known to activate RhoA57, further contributing to BBB disruption in seropositive patients and potentially increasing neuroinvasion.

In light of the concerns that ARVd can contribute to neurotoxicity in HIV-1 infection, we employed a mouse adapted strain of HIV called EcoHIV/NDK in which the viral gp120 protein was replaced with gp80 for the tropism to mouse cells78,79,80,81. To mimic a natural route of infection while promoting CNS entry, virus was inoculated by infusion via the internal cerebral artery. This technique induces a strong preference for CNS infection in the infused hemisphere. Compared to mock infection, we did not observe any differences in claudin-5 expression in either the vehicle- or Efavirenz-treated group. Nevertheless, brain infection with EcoHIV/NDK diminished expression of ZO-1 intensity in brain microvessels. This decreased expression corresponded to the impact of Efavirenz treatment, and no further reduction was observed in the HIV plus Efavirenz group as compared to HIV or Efavirenz alone. The link between ZO-1 and HIV has previously been identified and was associated, at least in part, to the toxic effect of HIV Tat protein82,83,84,85.

While several diseases are associated with HIV infection, cerebrovascular events are among the leading causes of mortality86,87,88. Therefore, we also evaluated the impact of NNRTI treatment on stroke in both mock or HIV infected mice. Our novel results indicate that Efavirenz treatment significantly increased stroke severity, inducing a two-fold increase in tissue damage as compared to controls. These results are consistent with the impact of this drug on claudin-5 expression and BBB integrity. HIV infection lead to a small increase in infarct volume in all treatment groups; however, it was below the threshold of significance.

In summary, our findings indicate that while HAART is an integral part of HIV treatment in seropositive patients, the choice of drugs used in the treatment regimen is crucial in preventing toxicity. Indeed, selected NNRTIs, such as Efavirenz, can deteriorate treatment outcome, especially in people subjected to cerebrovascular disease.

Material and Methods

Cell culture and virus stock preparation

Human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC; hCMEC/D3 cell line) were obtained by immortalizing human brain microvascular cells89. The cells are very well characterized and have been widely used in the literature, including our studies on ARVd toxicity89. The cells were cultured in EBM-2 medium (Lonza) supplemented with VEGF, IGF-1, EGF, basic FGF, hydrocortisone, ascorbate, gentamycin, and 0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonza) in cell culture dishes coated with rat-tail collagen I (BD Bioscience) in 5% CO2 humid incubator at 37 °C. HEK293T/17 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Primary human brain endothelial cells (Cell Systems) were cultured in CSC complete medium on dishes coated with CSC attachment factor (all from Cell Systems).

Chimeric HIV virus EcoHIV/NDK was used for mouse infection. EcoHIV/NDK was generated by replacing the viral gp120 protein with gp80 for the ecotropic moloney murine leukemia virus78. The viral plasmid was a kind gift from Dr. David Volsky (Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, NY). Viral stocks were prepared by transfecting HEK 293 T/17 cells with the plasmid using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Viral concentration in the filtered supernatant was quantified using p24 ELISA kit (Zeptometrix).

Drugs and inhibitor treatment

Exposure to NNRTIs was conducted in serum-free and antibiotic-free media for 48 h at the following concentrations: Efavirenz (1, 5, 10, and 15 μM), Etravirine (1.6 μM), Rilpivirine (0.5 μM), and Nevirapine (7.8 μM). These concentrations reflect physiological plasma concentrations of the drugs90,91. Regarding Efavirenz levels, both 10 and 15 μM are relevant to human exposure. While the mean plasma concentration of Efavirenz can vary from 3.17 to 12.67 μM in the majority of patients, a proportion of them (up to 14% in some studies) exhibit even higher concentrations91. ARVds were acquired from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (NIAID, Germantown, MD).

Activation of ER stress was blocked using the following inhibitors: GSK2606414 (7 μM), STF-083010 (10 μM), 4 μ8c (3 μM) (All EMD-Millipore) and 4-phenylbutyrate (2 mM, Sigma-Aldrich). Pre-exposure to ER stress inhibitors was initiated 6 h before NNRTI treatment.

Animal treatment, infection with EcoHIV/NDK, and the middle cerebral artery occlusion procedure

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Male C57BL/6 J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were allowed to acclimatize to the animal facility for one week with free access to food and water. They were then infused with EcoHIV/NDK (200 ng of p24) into the internal carotid artery using a method previously described58,92,93. Control animals received saline. Administration of NNRTIs started seven days post infection, and lasted for 30 days. Mice were gavaged daily with either 12.5% DMSO in saline (control), 10 mg/kg Efavirenz, 6.6 mg/kg Etravirine, or 0.42 mg/kg Rilpivirine (NIH AIDS Reagent Program). Afterward, mice were sacrificed for microvessels isolation or were used for in vivo BBB permeability assay or stroke studies.

Stroke was induced following the drug administration by the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) as described59,94. Briefly, occlusion was performed by insertion a silicone coated suture (Doccol) into the common cerebral artery and blocking blood flow to the middle cerebral artery for 60 min. Afterward, the suture was removed and blood flow restored for 23 h. Brains were harvested, sliced using a 1 mm brain matrix (Braintree Scientific) and stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, ThermoFisher). The images were captured using a digital camera and infarct volume was analyzed using Image J.

Permeability assays

In vitro endothelial permeability assays were performed in 12 wells, 0.4 μm Transwells plates (Corning) using either hCMEC (seeded at 6 × 104 cells per insert) or human primary brain endothelial cells (seeded at 5 × 104 cells per insert). Medium was changed every 48 h and monolayer formation was monitored using trans-epithelial electrical resistance. Seven days after seeding, medium was changed in the upper chamber for one containing treatment factors. Following exposure, media was replaced with Hanks balanced salt solution in both chambers; however, fluorescently tagged dextran (10, 40 or 70 kDa) was added to the upper chamber at the concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Fluorescent marker translocation was analyzed after 90 min incubation by transferring 100 μl aliquots from the lower chamber to a 96 well plaque and reading fluorescence at 485 nm (Ex) and 525 nm (Em).

In vivo BBB permeability assay was performed using sodium fluorescein (NaF) as described before95. Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of 10% NaF solution, which was allowed to circulate for 20 min. Mice were euthanized, blood was collected via heart puncture, and animals were perfused using normal saline. Brain hemispheres were thoroughly homogenized in PBS using a tissuelyser system (Qiagen) and cleared of debris by centrifugation. Sample protein concentration was measured to normalize the results. Proteins were precipitated with 100% TCA (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by centrifugation. Supernatants were mixed with 0.05 M sodium tetraborate buffer and NaF florescence was measured in the supernatants using a fluorescent plate reader (485 nm Ex, and 525 nm, Em). In addition to the brain, plasma NaF levels were assessed to control for injection variation.

Immunoblotting and immunostaining

Cells were exposed to vehicle or NNRTIs in 100 mm dishes, washed, and lysed in RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biochemical) containing protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Cell Signaling) 48 h post-exposure, unless otherwise stated. Protein concentration was assessed using a BCA protein assay (Pierce), and 20 μg of protein per sample was loaded on a TGX 4–20% gradient gel (Biorad). Transfer was performed on a nitrocellulose membrane using a Trans-blot Turbo system (Biorad). Afterward, membranes were blocked in 4% BSA in TBS. Primary antibodies were incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature in blocking buffer supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 and applied at the following concentrations: 1:1000 (claudin-5, Cell Signaling (Rb) and Invitrogen (Ms); claudin-5 (P-Y217), Abcam; ZO-1, Invitrogen; occludin, Invitrogen) or 1:10,000 (Tubulin, Sigma). Membranes were imaged in a Licor CLX imaging system with the secondary antibodies diluted at 1:20 000 (anti-rabbit 800CW and anti-mouse 680RD, Licor). Signal quantification was performed using Image Studio 4.0 software (Licor).

Immunostaining was performed on cultured cells or isolated microvessels, which were heat-fixed on slides and processed as previously described25. Samples were stained with rabbit antibodies against claudin-5 (Abcam) and ZO-1 (Cell Signaling), or with mouse antibodies against claudin-5 (Invitrogen) and occludin (Invitrogen). Alexa-488 and -594 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used for target detection; DRAQ5 (Cell Signaling) was employed to stain cell nuclei. Imaging was performed on an Olympus Fluoview 1200 confocal microscope with a 60x oil immersion lens, and analyzed using ImageJ software.

HIV detection by in situ PCR

In situ PCR was used to detect cells infected with HIV. Brains of mice either mock- or EcoHIV/NDK infected were harvested 1 week post infection, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, sliced at 10 μm, and kept at −80 °C until analysis. Slides were processed for in situ PCR as described96. Briefly, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h at room temperature and then digested using protease K at 5 μg/ml for 12 min at 25 °C. The enzyme was inactivated by a 95 °C incubation for 2 min. PCR mixture was prepared as described96, but modified for primers labeled with Alexa-594 to directly detect the PCR product. The following primers were used: NDK_F 5′-ALEXA 594-GGACCACAGGCTACACTAGAAG; NDK_R 5′-CAGCCAAAACTCTTGCTTTATG. Slide PCR was performed using an Xmatrx mini (Biogenex) cycler and Frame-seal slide chambers (Biorad). Slides were fixed at 92 °C for 1 min, stained with DRAQ5, and washed twice in 2x saline sodium citrate buffer. Imaging was performed as described in the section on immunofluorescence.

Real-time PCR

mRNA was isolated using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed by reverse transcription system (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Real time PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystem 7500 System and primers and probes for claudin-5, ZO-1 and occludin (ThermoFisher). GAPDH mRNA level was assessed in duplication for data normalization.

Tissue detection of EcoHIV/NDK was performed 1 week post infection. Tissue was harvested and processed using All Prep DNA/RNA isolation kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed as described above. HIV detection was then conducted using the following primers and probe: NDKgag_F 5′-GACATAAGACAGGGACCAAAGG; NDKgag_R 5′-CTGGGTTTGCATTTTGGACC; NDKgag_Probe 5′-AACTCTAAGAGCCGAGCAAGCTTCAC. Normalization was conducted based on GAPDH for RNA or mouse HBB for DNA80.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bertrand, L. et al. Antiretroviral Treatment with Efavirenz Disrupts the Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Increases Stroke Severity. Sci. Rep. 6, 39738; doi: 10.1038/srep39738 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ARVds were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Pathogenesis and Basic Research Branch, Division of AIDS NIAID. EcoHIV-NDK viral plasmid was obtained from Dr. David J. Volsky, Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, NY. This work was supported by the NIH (MH098891, MH072567, HL126559, DA039576, DA027569, and by the Miami Center for AIDS Research funded by NIH Grant MH063022). LB is supported by an AHA postdoctoral fellowship (16POST31170002).

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.B. and M.T. participated in research design, wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and provided funding; L.B. and L.D. conducted experiments; L.B. performed data analysis.

References

- Vance D. E. Aging with HIV: clinical considerations for an emerging population. Am J Nurs 110, 42–47; quiz 48–49, doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368952.80634.42 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola D. Demographics of HIV and aging. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9, 294–301, doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000076 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia N. S. & Chow F. C. Neurologic Complications in Treated HIV-1 Infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 16, 62, doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0666-1 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Iguacel R., Negredo E., Peck R. & Friis-Moller N. Hypertension Is a Key Feature of the Metabolic Syndrome in Subjects Aging with HIV. Curr Hypertens Rep 18, 46, doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0656-3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasi M. et al. Aging and inflammation in patients with HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol, doi: 10.1111/cei.12814 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduka C., Sarki A., Uthman O. & Stranges S. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on serum lipoprotein levels and dyslipidemias: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 199, 307–318, doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.052 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Ettorre G. et al. What happens to cardiovascular system behind the undetectable level of HIV viremia? AIDS Res Ther 13, 21, doi: 10.1186/s12981-016-0105-z (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas D. W. & Tarr P. E. Perspectives on pharmacogenomics of antiretroviral medications and HIV-associated comorbidities. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 10, 116–122, doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000134 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji H., Jager H. R. & Winston A. HIV, dementia and antiretroviral drugs: 30 years of an epidemic. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84, 1126–1137, doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304022 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Peripheral neuropathy in ART-experienced patients: prevalence and risk factors. J Neurovirol 19, 557–564, doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0216-4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman M. G., Schneider M., Nanau R. M. & Parry C. HIV-Antiretroviral Therapy Induced Liver, Gastrointestinal, and Pancreatic Injury. Int J Hepatol 2012, 760706, doi: 10.1155/2012/760706 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira N. M., Ferreira F. A., Yonamine R. Y. & Chehter E. Z. Antiretroviral drugs and acute pancreatitis in HIV/AIDS patients: is there any association? A literature review. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 12, 112–119 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikman A. E., Schonfeld E., Srisarajivakul N. C. & Poles M. A. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Diarrhea: Still an Issue in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy. Dig Dis Sci 60, 2236–2245, doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3615-y (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada V. et al. Relationship between plasma bilirubin level and oxidative stress markers in HIV-infected patients on atazanavir- vs. efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med, doi: 10.1111/hiv.12368 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprise C., Baril J. G., Dufresne S. & Trottier H. Atazanavir and other determinants of hyperbilirubinemia in a cohort of 1150 HIV-positive patients: results from 9 years of follow-up. AIDS Patient Care STDS 27, 378–386, doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaraldi G., Stentarelli C., Zona S. & Santoro A. HIV-associated lipodystrophy: impact of antiretroviral therapy. Drugs 73, 1431–1450, doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0108-1 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis A. M., Heverling H., Pham P. A. & Stolbach A. A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol 10, 26–39, doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0325-8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragovic G. & Jevtovic D. The role of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors usage in the incidence of hyperlactatemia and lactic acidosis in HIV/AIDS patients. Biomed Pharmacother 66, 308–311, doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.09.016 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Li Y., Peng K. & Zhou H. HIV protease inhibitors in gut barrier dysfunction and liver injury. Curr Opin Pharmacol 19, 61–66, doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.008 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Delfin J. et al. Effects of nevirapine and efavirenz on human adipocyte differentiation, gene expression, and release of adipokines and cytokines. Antiviral Res 91, 112–119, doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.04.018 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A., Hirschel B., Cooper D. A. & Carr A. A new era of antiretroviral drug toxicity. Antivir Ther 14, 165–179 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova N. et al. Involvement of nitric oxide in the mitochondrial action of efavirenz: a differential effect on neurons and glial cells. J Infect Dis 211, 1953–1958, doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu825 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell P. R. & Fox H. S. Efavirenz induces neuronal autophagy and mitochondrial alterations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 351, 250–258, doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.217869 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova N. et al. ER stress in human hepatic cells treated with Efavirenz: mitochondria again. J Hepatol 59, 780–789, doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand L. & Toborek M. Dysregulation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Autophagic Responses by the Antiretroviral Drug Efavirenz. Mol Pharmacol 88, 304–315, doi: 10.1124/mol.115.098590 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow F. C. HIV infection, vascular disease, and stroke. Semin Neurol 34, 35–46, doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372341 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiros-Roldan E. et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events in HIV-positive patients compared to general population over the last decade: a population-based study from 2000 to 2012. AIDS Care. 1–8, doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1198750 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovbiagele B. & Nath A. Increasing incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with HIV infection. Neurology 76, 444–450, doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820a0cfc (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs M. R. & Berger J. R. Stroke in HIV infection and AIDS. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 7, 1263–1271, doi: 10.1586/erc.09.72 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin L. A. et al. HIV infection and stroke: current perspectives and future directions. Lancet Neurol 11, 878–890, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70205-3 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow F. C. et al. Comparison of ischemic stroke incidence in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients in a US health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 60, 351–358, doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825c7f24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna D. B. et al. HIV Infection Is Associated With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis 61, 640–650, doi: 10.1093/cid/civ325 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruse B., Cysique L. A., Markus R. & Brew B. J. Cerebrovascular disease in HIV-infected individuals in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol 18, 264–276, doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0092-3 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Garre D. et al. Association of HIV-Infection and antiretroviral therapy with levels of endothelial progenitor cells and subclinical atherosclerosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 61, 545–551, doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826afbfc (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon S. & Carr A. Cardiovascular risk and body-fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med 352, 48–62, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041811 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. et al. Efavirenz Causes Oxidative Stress, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Autophagy in Endothelial Cells. Cardiovasc Toxicol 16, 90–99, doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9314-2 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa M. et al. HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy lead to unfolded protein response activation. Virol J 12, 77, doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0298-0 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattab S. et al. Soluble biomarkers of immune activation and inflammation in HIV infection: impact of 2 years of effective first-line combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 16, 553–562, doi: 10.1111/hiv.12257 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moren C. et al. Mitochondrial and apoptotic in vitro modelling of differential HIV-1 progression and antiretroviral toxicity. J Antimicrob Chemother 70, 2330–2336, doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv101 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaney J. & Campbell M. The dynamic blood-brain barrier. FEBS J 282, 4067–4079, doi: 10.1111/febs.13412 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qosa H., Miller D. S., Pasinelli P. & Trotti D. Regulation of ABC efflux transporters at blood-brain barrier in health and neurological disorders. Brain Res 1628, 298–316, doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.07.005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins R. A., O’Kane R. L., Simpson I. A. & Vina J. R. Structure of the blood-brain barrier and its role in the transport of amino acids. J Nutr 136, 218S–226S (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornford E. M. & Hyman S. Localization of brain endothelial luminal and abluminal transporters with immunogold electron microscopy. NeuroRx 2, 27–43, doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.27 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R. & Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a020412, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosa J. A., Morrison H. W., Iddings J. A., Du W. & Kim K. J. Beyond neurovascular coupling, role of astrocytes in the regulation of vascular tone. Neuroscience 323, 96–109, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.064 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M. D., Ayyadurai S. & Zlokovic B. V. Pericytes of the neurovascular unit: key functions and signaling pathways. Nat Neurosci 19, 771–783, doi: 10.1038/nn.4288 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier B., Daneman R. & Ransohoff R. M. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med 19, 1584–1596, doi: 10.1038/nm.3407 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frechou M. et al. Intranasal delivery of progesterone after transient ischemic stroke decreases mortality and provides neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology 97, 394–403, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.06.002 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. et al. Attenuation of acute stroke injury in rat brain by minocycline promotes blood-brain barrier remodeling and alternative microglia/macrophage activation during recovery. J Neuroinflammation 12, 26, doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0245-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferkorn T. & Rosenberg G. A. Closure of the blood-brain barrier by matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces rtPA-mediated mortality in cerebral ischemia with delayed reperfusion. Stroke 34, 2025–2030, doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083051.93319.28 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi T. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces retinal endothelial permeability of extracellular-superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Res 45, 1083–1092, doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.595408 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca A. C., Ferreiro E., Oliveira C. R., Cardoso S. M. & Pereira C. F. Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response by the amyloid-beta 1-40 peptide in brain endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832, 2191–2203, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.08.007 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko A. R., Kim J. Y., Hyun H. W. & Kim J. E. Endothelial NOS activation induces the blood-brain barrier disruption via ER stress following status epilepticus. Brain Res 1622, 163–173, doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.020 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingat F. et al. Inflammation and epithelial cell injury in AIDS enteropathy: involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress. FASEB J 25, 2211–2220, doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175992 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan D., Lau Y. S., Lau C. W., Mustafa M. R. & Huang Y. Angiotensin 1-7 Protects against Angiotensin II-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction via Mas Receptor. PLoS One 10, e0145413, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145413 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampakakis E. et al. Intravenous Lipid Infusion Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Endothelial Cells and Blood Mononuclear Cells of Healthy Adults. J Am Heart Assoc 5, doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002574 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y. et al. Rho-mediated regulation of tight junctions during monocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier in HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE). Blood 107, 4770–4780, doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4721 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leda A. R., Dygert L., Bertrand L. & Toborek M. Mouse Microsurgery Infusion Technique for Targeted Substance Delivery into the CNS via the Internal Carotid Artery. JOVE (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand L., Dygert L. & Toborek M. Induction of ischemic stroke and ischemia-reperfusion in mice using the middle artery occlusion technique and visualization of infarct area. JOVE (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Picado J. & Deeks S. G. Persistent HIV-1 replication during antiretroviral therapy. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 11, 417–423, doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Z. et al. Specific binding of a mutated fragment of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin to endothelial claudin-5 and its modulation of cerebral vascular permeability. Neuroscience 327, 53–63, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.04.013 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku J. M. et al. Protective actions of des-acylated ghrelin on brain injury and blood-brain barrier disruption after stroke in mice. Clin Sci (Lond), doi: 10.1042/CS20160077 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Rhubarb attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption via increased zonula occludens-1 expression in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp Ther Med 12, 250–256, doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3330 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. M., Yuan F., Liu Y. L., Ding J. & Tian H. L. Glibenclamide attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in adult mice following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma, doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4491 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C. et al. Limb Ischemic Perconditioning Attenuates Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption by Inhibiting Activity of MMP-9 and Occludin Degradation after Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Aging Dis 6, 406–417, doi: 10.14336/AD.2015.0812 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta T. et al. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 161, 653–660, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302070 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cominacini L. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Nrf2 signaling in cardiovascular diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 88, 233–242, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.027 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. et al. Coronary Microembolization Induces Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis Through the LOX-1-Dependent Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway Involving JNK/P38 MAPK. Can J Cardiol 31, 1272–1281, doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.013 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Trudeau K., Roy S., Tien T. & Barrette K. F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic retinopathy: mechanistic insights into high glucose-induced retinal cell death. Curr Clin Pharmacol 8, 278–284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T. et al. Diabetes and Age-Related Differences in Vascular Function of Renal Artery: Possible Involvement of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Rejuvenation Res 19, 41–52, doi: 10.1089/rej.2015.1662 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimellaro A., Perticone M., Fiorentino T. V., Sciacqua A. & Hribal M. L. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in endothelial dysfunction. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2016.05.008 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi T., Teramachi M., Yasuda H., Kamiya T. & Hara H. Contribution of p38 MAPK, NF-kappaB and glucocorticoid signaling pathways to ER stress-induced increase in retinal endothelial permeability. Arch Biochem Biophys 520, 30–35, doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.01.014 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. A., Yoon J. C., Kim M. & Park E. M. Activation of classical estrogen receptor subtypes reduces tight junction disruption of brain endothelial cells under ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med 92, 78–89, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.01.010 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. et al. Advanced oxidation protein products induce endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human renal glomerular endothelial cells through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Diabetes Complications 30, 573–579, doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.01.009 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awan F. M. et al. In-silico analysis of claudin-5 reveals novel putative sites for post-translational modifications: Insights into potential molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier breach during HIV-1 infiltration. Infect Genet Evol 27, 355–365, doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.07.022 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M. et al. Phosphorylation of claudin-5 and occludin by rho kinase in brain endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 172, 521–533, doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070076 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada S. et al. Ca2+-dependent activation of Rho and Rho kinase in membrane depolarization-induced and receptor stimulation-induced vascular smooth muscle contraction. Circ Res 93, 548–556, doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000090998.08629.60 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash M. J. et al. A mouse model for study of systemic HIV-1 infection, antiviral immune responses, and neuroinvasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 3760–3765, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500649102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadas E. et al. Transmission of chimeric HIV by mating in conventional mice: prevention by pre-exposure antiretroviral therapy and reduced susceptibility during estrus. Dis Model Mech 6, 1292–1298, doi: 10.1242/dmm.012617 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H. et al. Enhanced human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 expression and neuropathogenesis in knockout mice lacking Type I interferon responses. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73, 59–71, doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000026 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindberg G. M. et al. An infectious murine model for studying the systemic effects of opioids on early HIV pathogenesis in the gut. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 10, 74–87, doi: 10.1007/s11481-014-9574-9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson D., Clarke S., Berry N. & Almond N. Attenuated SIV causes persisting neuroinflammation in the absence of a chronic viral load and neurotoxic ART. AIDS, doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001178 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S. et al. HIV-1 impairs human retinal pigment epithelial barrier function: possible association with the pathogenesis of HIV-associated retinopathy. Lab Invest 94, 777–787, doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.72 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Eum S. Y., Andras I. E., Hennig B. & Toborek M. PPARalpha and PPARgamma attenuate HIV-induced dysregulation of tight junction proteins by modulations of matrix metalloproteinase and proteasome activities. FASEB J 23, 1596–1606, doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121624 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Zhang B., Eum S. Y. & Toborek M. HIV-1 Tat triggers nuclear localization of ZO-1 via Rho signaling and cAMP response element-binding protein activation. J Neurosci 32, 143–150, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4266-11.2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. J. et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet 384, 241–248, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldaz P. et al. Mortality by causes in HIV-infected adults: comparison with the general population. BMC Public Health 11, 300, doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-300 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima M. et al. Cause of death in HIV-infected patients in South Carolina (2005-2013). Int J STD AIDS 27, 25–32, doi: 10.1177/0956462415571970 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler B., Romero I. A. & Couraud P. O. The hCMEC/D3 cell line as a model of the human blood brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 10, 16, doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-10-16 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usach I., Melis V. & Peris J. E. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: a review on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability. J Int AIDS Soc 16, 1–14, doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18567 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzolini C. et al. Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 15, 71–75 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff G., Davidson S. J., Wrobel J. K. & Toborek M. Exercise maintains blood-brain barrier integrity during early stages of brain metastasis formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 463, 811–817, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.153 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel J. K., Wolff G., Xiao R., Power R. F. & Toborek M. Dietary Selenium Supplementation Modulates Growth of Brain Metastatic Tumors and Changes the Expression of Adhesion Molecules in Brain Microvessels. Biol Trace Elem Res 172, 395–407, doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0595-x (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. et al. Deficiency of telomerase activity aggravates the blood-brain barrier disruption and neuroinflammatory responses in a model of experimental stroke. J Neurosci Res 88, 2859–2868, doi: 10.1002/jnr.22450 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Kim H. J., Lim B., Wylegala A. & Toborek M. Methamphetamine-induced occludin endocytosis is mediated by the Arp2/3 complex-regulated actin rearrangement. J Biol Chem 288, 33324–33334, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483487 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagasra O. Protocols for the in situ PCR-amplification and detection of mRNA and DNA sequences. Nat Protoc 2, 2782–2795, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.395 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.