Abstract

Introduction

Prolonged neutrophil infiltration leads to exaggerated inflammation and tissue damage during sepsis. Neutrophil migration requires rearrangement of their cytoskeleton. Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-factor VIII (MFG-E8)-derived short peptide 68 (MSP68) has recently been shown to be beneficial in sepsis-induced tissue injury and mortality. We hypothesize that MSP68 inhibits neutrophil migration by modulating small GTPase Rac1 dependent cytoskeletal rearrangements.

Methods

Bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDN) or whole lung digest isolated neutrophils were isolated from 8–10 week old C57BL/6 mice by percoll density gradient centrifugation. The purity of BMDN was verified by flow cytometry with CD11b/Gr-1 staining. Neutrophils were stimulated with f-MLP (10 nM) in presence or absence of MSP68 at10 nM or cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) was utilized to induce sepsis, and MSP68 was administered at 1mg/kg intravenously. Cytoskeletal organization was assessed by phalloidin staining, followed by analysis using fluorescence microscopy. Activity of the Rac1 GTPase in f-MLP or CLP activated BMDN in the presence or absence of MSP68 was assessed by GTPase ELISA (GLISA). Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase activity was determined by western blot densitometry.

Results

BMDN treatment with f-MLP increased cytoskeletal remodeling as revealed by the localization of filamentous actin (F-actin) to the periphery of the neutrophil. By contrast, cells pre-treated with MSP68 had considerably reduced F-actin polymerization. Cytoskeletal spreading is associated with the activation of the small GTPase Rac1. We found BMDN-treated with f-MLP or that were exposed to sepsis by CLP had increased Rac1 signaling, while the cells pre-treated with MSP68 had significantly reduced Rac1 activation (p<0.05). MAP kinases related to cell migration including pP38 and pERK were up-regulated by treatment with f-MLP. Up-regulation of these MAP kinases was also significantly reduced after pre-treatment with MSP68 (p<0.05).

Conclusions

MSP68 down-regulates actin cytoskeleton dependent, Rac1-MAP kinase-mediated neutrophil motility. Thus, MSP68 is a novel therapeutic candidate for regulating inflammation and tissue damage caused by excessive neutrophil migration in sepsis.

Keywords: Sepsis, MFG-E8, MSP68, Lung, Bone-marrow, Neutrophil, Small GTPase, Rac1

Introduction

Sepsis is a cytopathologic inflammatory syndrome associated with infection which culminates in organ dysfunction and death1. Hospitalization rates for sepsis have increased by an average of 11.9% per year since the turn of the century2,3. Efforts to improve sepsis related outcomes have included a number of targets and treatment protocols. Past attempts have focused on bacterial targets 4, immunosuppression5, and secreted inflammatory mediators 6–8. Progress has been fitful and an impressive litany of setbacks has frustrated efforts to introduce new drugs and treatments for sepsis9–12.

Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-factor VIII (MFG-E8) is a secretory glycoprotein produced by the milk duct epithelium and immune reactive cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells that has been shown to decrease both morbidity and mortality in sepsis13, 14. MFG-E8 has epidermal growth factor like domain which recognize the αvβ3-integrin of macrophages and a domain sharing homology with the coagulation protein factor VIII, capable of recognizing exposed phosphatidylserine (PS) on apoptotic cells. These two domains of MFG-E8 promote the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages15, 16. Recently, the therapeutic functions of MFG-E8 in acute lung injury (ALI) have been reported to be directly mediated through the inhibition of neutrophil migration in the lung17, 18.

Our group recently screened a large number of human MFG-E8-derived peptides based on their ability to inhibit neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells (EC) and their subsequent migration toward chemokines19. The functional domain of MFG-E8 responsible for retardation of neutrophil motility was identified to be a penta-peptide flanking an arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) motif which recognizes αvβ3-integrin on immune cells 19. This functionally active molecule was named MFG-E8-derived short peptide 68 (MSP68)19.

During acute inflammation neutrophils transmigrate into the inflamed tissue from the vascular lumen by passing through the endothelial cells20, 21. Transmigration requires remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton22. The role that Rho family GTPases Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 play in cytoskeletal rearrangement is well studied23, 24. Studies in knockout mice have demonstrated the importance of Rac1 in cytoskeletal regulation25, 26. Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases like P38 and ERK also act as important players in a number of pathways central to neutrophil transmigration, including integrin mediated signaling27, 28. An agent targeting these pathways has the potential to reduce the damaging excessive infiltration of neutrophils associated with sepsis.

Neutrophil infiltration into tissues is followed by a diverse set of end functions including pathogen engulfment, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, leukocyte recruitment, elaboration of elastases, and extracellular trap deployment29. The consequences of these processes can be devastating for the organ tissues involved30. We have recently reported that administration of MSP68 into septic animals dramatically reduced neutrophil infiltration into the lungs and improved mortality19. However, any agent that decreases leukocyte infiltration and function could be deleterious in certain clinical settings. Profound immunosuppression is a devastating feature of late sepsis and an agent that compromises immune function may not be well placed to improve patient outcomes in late sepsis. Previously we have shown that treatment with MSP68 does not affect neutrophil mediated killing as measured by myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and direct bacterial killing assay19. This suggests that MSP68 can act to modulate immune cell activity without compromising pathogen clearance. Despite the beneficial outcomes of MSP68 in animal models of sepsis, the underlying mechanism for protection against ALI and neutrophil migration has not been elucidated.

In the current study, we hypothesized that MSP68 had direct effects on regulating neutrophil migration by modulating the cytoskeletal architecture in the context of sepsis. In this study, we show that MSP68 ameliorated the activation of canonical intracellular signaling cascades that are associated with the Rac1-dependent cytoskeletal remodeling and that these changes are responsible for decreased neutrophil infiltration and inflammation. This points to an emerging paradigm: the cytoskeleton as immunomodulator31. Several leukocyte functions require the cytoskeletal to undergo changes in organization and assembly state such as diapedesis and phagocytosis, so the cytoskeleton is well positioned to act as an immunomodulator. Thus, MSP68 could serve as a novel therapeutic candidate for regulating excessive neutrophil migration in lungs during sepsis.

Material and Methods

Preparation of MSP68

The peptide sequence of MSP68 was designed as described previously19. Briefly, MSP68 is a penta-peptide prepared from human MFG-E8 protein sequences, which contained an RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartate) motif flanked by valine residues on both sides (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Isolation and Purification of Bone Marrow-derived Neutrophils

Eight week old C57BL/6 mice from Taconic Biosciences (Albany, NY) were used for this study. Mice were raised in a climate controlled and day-light cycled facility and fed standard chow in compliance with the guidelines for use of experimental animals mandated by the National Institutes of Health. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. After euthanasia, mice femurs and tibias were dissected from the hind legs and removed. Femurs were cut at both epiphyses and the marrow was flushed out with Ca++ and Mg++ free Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; Mediatech, Manassas, VA) through a 25 gauge needle into a petri dish resting on ice. Marrow suspensions were filtered through a 70 micron cell strainer (Corning Inc, NY), followed by centrifugation at 100 g for 10 min at 4°C. A PBS diluted Percoll (Sigma, St. Louis MO) gradient with 78%, 69%, and 52% layers was created and the bone marrow-derived neutrophil (BMDN) pellet was resuspended in HBSS and over-layered onto this gradient. The Percoll gradient was centrifuged for 30 min at 1300 g. BMDNs were collected from the 78%/69% interface and washed in ACK lysing buffer (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) for 5 min then washed by suspension in HBSS and centrifuged at 100 g for 10 min. To assess the purity of primary neutrophils isolated from mouse bone marrow, we used PE anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1) Ab (Clone: RB6–8C5, BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Gr-1 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked myeloid differentiation antigen expressed on granulocytes and macrophages. Aside from neutrophils, to rule out the possibility of macrophage contamination, during the assessment of the purity of BMDN by flow cytometry, the cells were gated based on their size and shape. We found that almost all the purified cells were laid on the high side scatter compartment, indicating these cells to be the granulocyte population with segmented and multi-lobed nucleus. In addition to this, we also performed a cytospin assay of our purified neutrophils, which indicated that these cells were purely neutrophil population (data not shown).

Sepsis Induction by Cecal Ligation and Puncture

Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and underwent cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as described previously32, 33. In summary, a 1.5-cm celiotomy was created, and the cecum exposed and ligated 1 cm from the tip with 4–0 silk suture. A 22-gauge needle was used to make one transverse puncture through and through the distal cecum, extruding a small amount of fecal material. The cecum was replaced into the abdominal cavity, and the abdomen was closed in two layers with running 6–0 silk suture. The sham mice underwent the same procedure, but without the ligation and puncture of their cecum. Animals were resuscitated with 1 ml of normal saline subcutaneously. Two hours after CLP, mice were either injected with 100 µl of PBS as vehicle or MSP68 at a dose of 1 mg/kg through the internal jugular vein. At 20 h after CLP, blood samples were collected for analyzing injury markers and lung tissues were harvested to isolate neutrophils for ex vivo Rac1 activity assay.

Analysis of Serum Aspartate Aminotransferase

Blood samples were drawn prior to euthanasia from the abdominal vena cava and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant containing the serum was collected and then analyzed for aspartate amino transferase (AST) as tissue injury marker immediately. AST levels were measured in serum using assay kits from Pointe Scientific (Canton, MI).

Lung Neutrophil Isolation

Eight week old C57BL/6 mice from Taconic Biosciences were used for this assay. After euthanasia, lungs were harvested, cut into fine pieces, and suspended in Ca++ and Mg++ free HBSS. Digestion was undertaken with 100 U/ml of Collagenase I (Worthington Biochem, Lakewood, NJ) and 20 U/ml DNase I (Worthington Biochem) at 37°C in a shaking path for 30 min with periodic vortexing. Tissue fragments were crushed with a 3 ml syringe plunger and flowed through a 70 micron filter with RPMI medium (Corning Inc, NY). Cells were then spun down at 500 g and suspended in RPMI medium. A PBS diluted Percoll gradient with 66% and 44% layers created and the neutrophil suspension was over-laid onto this gradient. The Percoll gradient was centrifuged for 20 min at 600 g. Lung neutrophils were collected from below the 66% to 44% interface and washed by suspension in RPMI and centrifuged at 100 g for 10 min after which they were suspended in RPMI media and counted.

Actin Polymerization Assay

Bone marrow-derived neutrophils were prepared as above and suspended in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco-Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Chambered cover glass slides were coated with poly-L lysine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and cell suspensions were added to the chambers. BMDNs were pre-treated with either PBS as vehicle or MSP68 at a dose of 10 mM for 30 min, followed by the stimulation with the N-formylmethionine-leucine-phenylalanine (f-MLP) (Tocris BioSci, Bristol, UK ) at 10 mM for 5 min. After activation with f-MLP, cells were fixed with 3.7% methanol free-formaldehyde in PBS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were then spun at 100 g for 5 min and supernatants were aspirated with fine glass pipette tip. Cells were washed in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 5 min and spun at 50 g for 5 min. Triton X-100 solution was aspirated and chambers were re-filled with 10 units/ml of phalloidin Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) and 0.5 µl/ml of Propidium Iodide (Sigma, St. Louis MO) nuclear stain in PBS containing 1% FBS overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed 2 times with PBS and visualized with a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Mean fluorescence intensity was calculated using NIS-Elements Software (Nikon, Melville, NY).

Western Blot Analysis

Bone marrow derived neutrophils were prepared as described above and separated into three groups. Cells were treated with PBS alone, f-MLP (10 mM) for 240 sec, or 15 min of MSP68 (10 mM) followed by f-MLP (10 mM) for 240 sec. Cells were rapidly pelleted at 7000 g for 60 seconds and arrested in liquid nitrogen bath. Pellets were resuspended in EDTA/EGTA containing lysis buffer and sonicated on ice then mixed with reducing sample buffer. Cells were then heated for 10 min at 95°C prior to gel electrophoresis (412% Bis-Tris: Novex, Life Tech., Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were transferred to 0.2 micron nitrocellulose paper (Novex). The blots were then reacted overnight at 4°C with primary monoclonal Abs for rabbit anti-mouse phosphoylated P38 (pP38) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and rabbit anti-mouse phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) (Cell Signaling). After reacting the blots with green fluorochrome-labeled-anti-rabbit secondary Abs proteins were detected by Odyssey system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE), followed by the quantitative densitometry analysis using Image J software.

Rac1 Activation Assay

The activation of Rac1 with or without MSP68 pre-treated was measured in f-MLP treated neutrophils, CLP induced sepsis BMDN neutrophils, or CLP induced sepsis lung neutrophils, using the Rac1 G-Lisa kit from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Catalog # BK128-S; Denver, CO). For in vitro Rac1 activation assay, a total of 1 × 106 BMDNs were either treated with PBS or MSP68 (10 mM) for 30 min, followed by the activation of the cells by f-MLP (10 mM) for 4 min then cells were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen to stop reactions. Frozen BMDN pellets were suspended in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) and sonicated briefly to perform protein extraction. Protein concentrations were measured with included Precision Red system (Cytoskeleton, Inc.). After processing, Rac1 activation was measured at 490 nm. Using similar approach, ex vivo Rac1 activation assay was carried-out in lung neutrophils harvested as described above from sham, CLP-treated with PBS or CLP-treated with MSP68 (1 mg/kg) i. v. mice.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SigmaPlot 12.5 graphing and statistical software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The data represented in the figures are means +/− the standard error of the mean. Analysis of variance was used for one-way comparisons between multiple groups and significance was determined by the Student-Newman-Keuls method. When only two groups were compared, the Student’s t test was employed. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

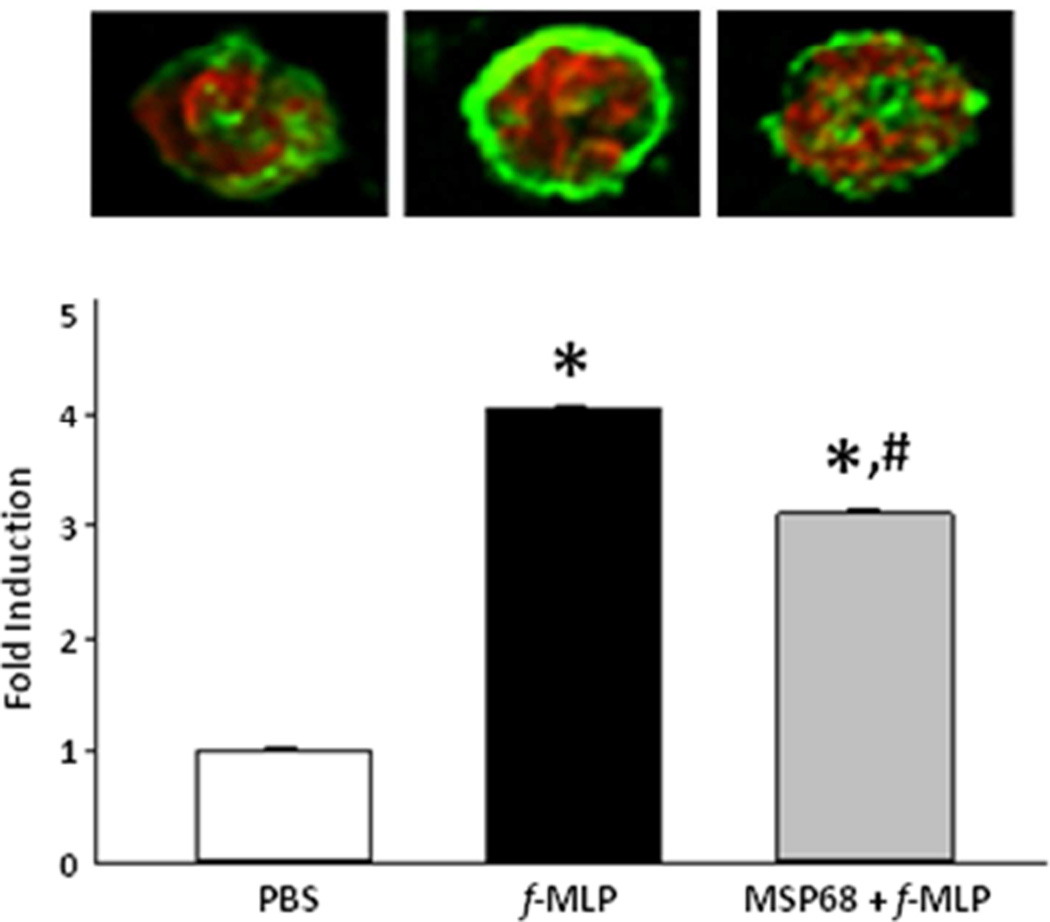

Treatment with MSP68 Inhibits Actin Polymerization in Murine Neutrophils

The actin cytoskeleton undergoes dynamic rearrangement during chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Taking advantage of phalloidin which binds only to filamentous actin, we found that f-MLP induced peripherilization and polymerization of filamentous actin and that filamentous actin expression was reduced in cells treated with MSP68 after stimulation with f-MLP (Fig 1). Quantitative assessment of the phalloidin fluorescence intensities revealed a 4 fold (p<0.05) up-regulation in f-MLP treated BMDN compared to the PBS-treated cells, while the cells treated with MSP68 significantly down-regulated the fluorescent intensities by 25.3% (p<0.05, n =10,000 fluorescent units per group) (Fig 1). Thus, MSP68-mediated reduced neutrophil migration in lungs as demonstrated in our previous study19, could be promoted through the attenuation of cytoskeletal rearrangement.

Figure 1.

Actin polymerization at 1000×. Phalloidin-Alexafluor488 labeled F-Actin in green. Propidium Iodide labeled nucleus in red. Male C57BL/6 were sacrificed and live bone marrow derived neutrophils were collected. These neutrophils were treated with PBS, f-MLP, or MSP68 followed by f-MLP. Cells stained with Alexafluor488 Phalloidin or Propidium Iodide. Mean fluorescence intensities at 488 nm from low powered fields were measured. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test (n=10,000 events/group). *P<0.05 vs. PBS, #P<0.05 vs. f-MLP.

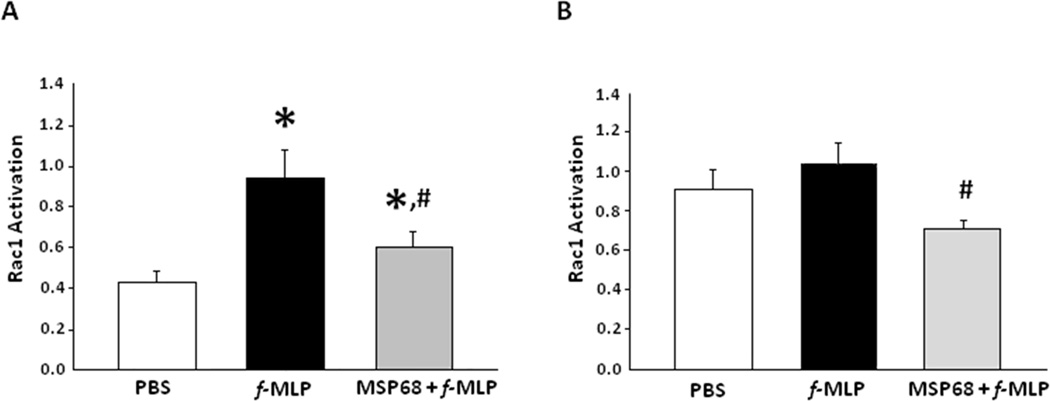

MSP68 Inhibits Rac1 Activation of Bone Marrow-derived Neutrophils

Rac, Rho, and Cdc42 have long been appreciated as key regulators of actin organization. At 15 seconds f-MLP activated BMDNs had significantly increased (2.38 fold, p<0.05) Rac1 signaling as measured by the amount of activated GTP bound Rac1 in neutrophils in vitro. However, this activation was significantly (46.9%, p<0.05) attenuated by in the presence of MSP68 (Fig 2A). Rac1 activation was measured again at 30 min, and MSP68 was able to significantly down-regulate the Rac1 signaling by 21.7% (p<0.05) as compared to the f-MLP treatment alone (Fig 2B), indicating persistent inhibitory effect of MSP68 on Rac1 activation.

Figure 2.

A. Rac1 signaling is increased in cells activated for 15 seconds with f-MLP. This signaling is attenuated by pretreatment with MSP68. BMDNs were collected from C57BL/6 mice and treated with PBS, f-MLP, or MSP68 then f-MLP. Cells were lysed and activated Rac1 ELISA was performed. Mean optical densities at 490 nm were assessed. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [PBS (n=6 mice), f-MLP (n=8 mice), MSP68+f-MLP (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. PBS, #P<0.05 vs. f-MLP.

B. Rac1 signaling is increased in cells activated for 30 minutes with f-MLP. This signaling is attenuated by pretreatment with MSP68. BMDNs were collected from C57BL/6 mice and treated with PBS, f-MLP, or MSP68 then f-MLP. Cells were lysed and activated Rac1 ELISA was performed. Mean optical densities at 490 nm were assessed. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [PBS (n=6 mice), f-MLP (n=8 mice), MSP68+f-MLP (n=8 mice)]. # P<0.05 vs. f-MLP.

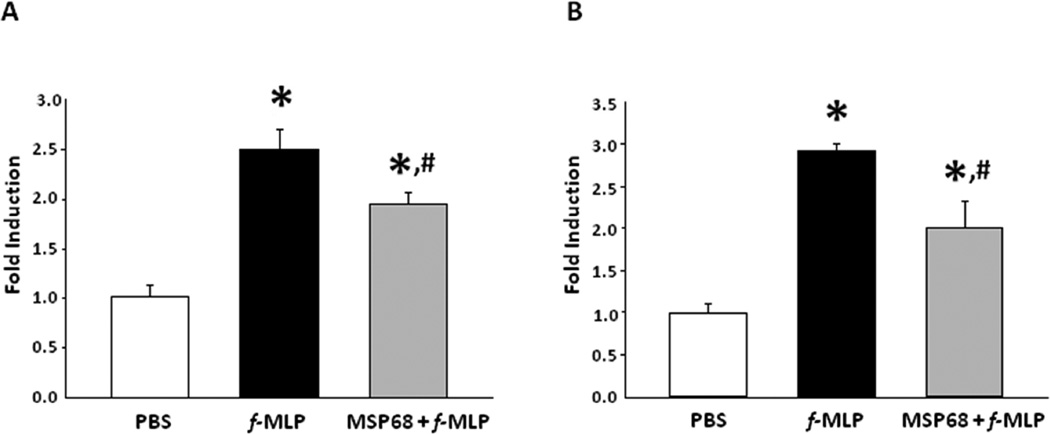

MSP68 Inhibits P38 and ERK Activation in Bone Marrow-derived Neutrophils

Mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase-mediated signal-transduction pathways convert extracellular stimulation into a variety of cellular events, involving neutrophil migration and their function34. They act downstream of Rac1 and are important for regulating the cytoskeleton. BMDN treated with f-MLP robustly increased the pP38 2.35 fold (p<0.05) and pERK 2.56 fold (p<0.05), while the cells pre-treated with MSP68 significantly down-regulated the phosphorylation of p38 22.8% (p<0.05) and pERK by 32.5% (p<0.05), respectively (Fig 3A, B).

Figure 3.

A. Expression of phosphorylated P38 after activation if f-MLP with or without MSP68 treatment. BMDNs were collected from C57BL/6 mice and treated with PBS, f-MLP, or MSP68 then f-MLP. Cells were lysed and a western blot was carried out using phosphorylated P38 primary antibody. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and StudentNewman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [PBS (n=6 mice), f-MLP (n=8 mice), MSP68+f-MLP (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. PBS, #P<0.05 vs. f-MLP.

B. Expression of phosphorylated P38 after activation if f-MLP with or without MSP68 treatment. BMDNs were collected from C57BL/6 mice and treated with PBS, f-MLP, or MSP68 then f-MLP. Cells were lysed and a western blot was carried-out using phosphorylated ERK1/2 primary antibody. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and StudentNewman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [PBS (n=6 mice), f-MLP (n=8 mice), MSP68+ f-MLP (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. PBS, #P<0.05 vs. f-MLP.

MSP68 Inhibits Sepsis-induced Rac1 Activation of Bone Marrow-derived Neutrophils

Recruitment of neutrophils from the bone marrow is a prerequisite for tissue infiltration in the setting of sepsis. We designed an experiment to test the effect that MSP68 had on Rac1 activation in bone marrow derived neutrophils in animals subjected to CLP induced sepsis. As shown in Fig 4, sepsis resulted in the significant up-regulation of Rac1 activity (2.03 fold, p<0.05) in BMDN compared to that of sham mice. However, septic animals treated with MSP68 significantly down-regulated the Rac1 activation in BMDN by 44 % (p<0.05) compared to the PBS-treated septic mice (Fig 4a).

Figure 4.

a. BMDN expression of activated Rac1 after cecal ligation and puncture induced sepsis. Two hours after CLP, MSP68 was given at 1 mg/kg. After 20 hours animals were sacrificed and live BMDNs were collected. Cells were lysed and activated Rac1 ELISA was performed. Mean optical densities at 490 nm were measured. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [Sham (n=6 mice), vehicle (n=8 mice), MSP68 (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. sham, #P<0.05 vs. vehicle.

b. Rac1 activation in the whole lung after induction of sepsis with cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Mice received either PBS or MSP68 two hours after CLP. At 20hrs mice were sacrificed and whole lungs were collected and digested with collagenase I and DNAase I yielding neutrophils. Cells were lysed and activated Rac1 ELISA was performed. Mean optical densities at 490 nm were measured. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and compared by oneway ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test, obtained from three independent experiments [Sham (n=6 mice), vehicle (n=8 mice), MSP68 (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. sham, #P<0.05 vs. vehicle.

MSP68 Inhibits Sepsis-induced Rac1 Activation in the Lungs

Acute lung injury is an important contributor to sepsis related morbidity and mortality. To determine if MSP68 played a role beyond the bone marrow we measured Rac1 activation in whole lung tissue. After CLP, Rac1 activation in lung was 1. 62 fold higher in CLP mice (p<0.05) than sham mice; however the mice treated with MSP68 had significantly reduced Rac1 activation (31%, p<0.05) compared to the PBS-treated animals (Fig 4b).

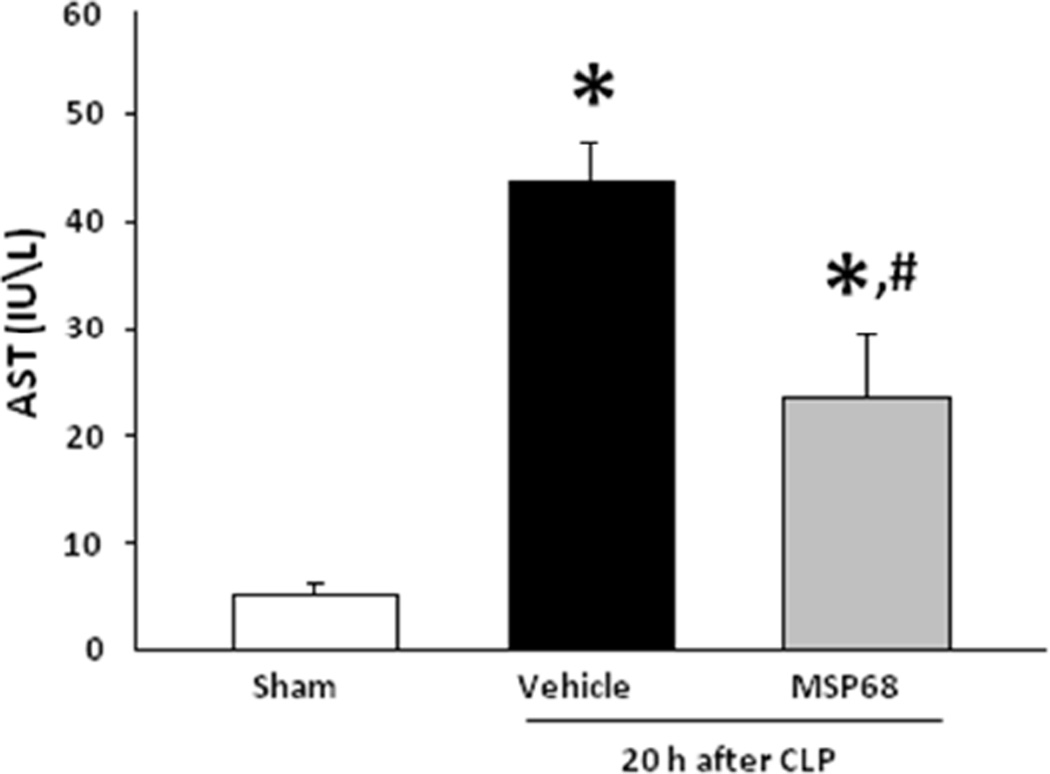

Treatment with MSP68 Reduces Sepsis-induced Tissue Damage

In order to verify the severity or our CLP model and prove that MSP68 ameliorates organ specific injury, we measured the levels of the AST in the blood. We observed that CLP induced an 8.58 fold (p<0.05) elevation in AST as compared to the sham mice and moreover, MSP68 significantly decreased the circulating AST by 54% (p<0.05) compared to the vehicle-treated animals (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Serum AST after CLP and treatment with or without MSP68. To verify severity of sepsis, levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured from venous blood. Elevation in AST was consistent with sepsis. MSP68 treatment prevented AST elevation. Data are expressed as mean±SEM and were compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test [Sham (n=6 mice), vehicle (n=8 mice), MSP68 (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. sham, #P<0.05 vs. vehicle.

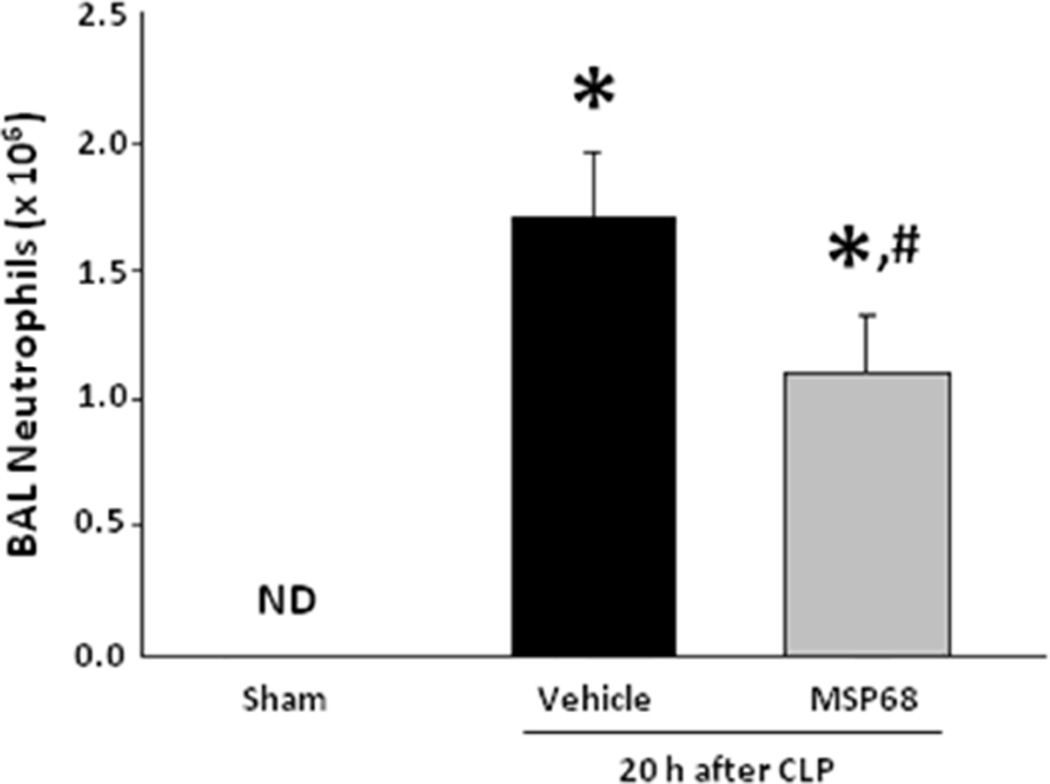

MSP68 Reduces Sepsis-induced Lung Neutrophil Infiltration

Neutrophil migration into the airways requires transit across endothelial and epithelial membranes. In order to test the hypothesis that MSP68 can reduce cell transmigration in vivo, we counted the number of infiltrated neutrophils from the BAL of mice exposed to CLP induced sepsis. As per our results, sepsis resulted in the significant increase in the numbers of neutrophils into the lung bronchoalveolar spaces as compared to the sham mice, while a marked decrease in neutrophil counts in the BAL fluid had been observed in mice treated with MSP68 by 27.6% (p<0.05) when compared to the vehicle-treated mice (Fig 6).

Figure 6.

BAL Absolute Neutrophil Count. Vehicle and MSP68 group were exposed to CLP and treated with PBS vehicle or MSP68 two hours later. After 20 h bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with HBSS. BAL fluid cell count was obtained and BAL fluid was stained with Gr1 for determination of neutrophil fraction by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were compared by one-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test [Sham (n=6 mice), vehicle (n=8 mice), MSP68 (n=8 mice)]. *P<0.05 vs. sham, #P<0.05 vs. vehicle.

Discussion

The neutrophil is central to the pathogenesis of sepsis related morbidity and mortality35. However, the neutrophil is also essential for overcoming the blood stream infections that cause the sepsis syndrome36. Considering this balance between pathogen clearance and exacerbating tissue injury, both mediated by neutrophils, an ideal treatment for sepsis should meet certain criteria: it must effectively reduce tissue injury and mortality, it should not inhibit pathogen clearance or expose patients to nosocomial infections, and it must be safe and effective in concert with a wide range of therapies.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that MFG-E8 and MSP68 are beneficial in attenuating sepsis-induced ALI by regulating excessive neutrophil infiltration at the tissue level19. In the current study we have postulated the intracellular mechanism by which MSP68 attenuated sepsis induced primary neutrophil migration. Members of the small Rho GTPase family, Rac-1, CDC42 and RhoA, serve as the central regulators of actin dependent cell migration23. By focusing on the role of MSP68 on Rac-1 activation in vitro and in vivo our study has determined MSP68 is an inhibitor of Rac-1-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling. This mechanism explains our earlier in vitro findings with respect to migration and in turn, the in vivo findings of reduced acute lung injury19.

In a prior study, our group took advantage of an LPS-induced ALI model and found that MFG-E8 down-regulates surface expression of the chemokine receptor, CXCR217. The inhibition of CXCR2 on neutrophils by MFG-E8 was thought to be mediated through the up-regulation of the G-protein coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2), which acts as a negative regulator of CXCR2 expression in neutrophils17. In the presence of chemokines neutrophils acquire their migration ability through the up-regulation of Rac123. The effect that MSP68 has on Rac1 activation was observable as early as 15 seconds with cytoskeleton organizational changes minutes after, long before any changes in surface expression of CXCR2 could take place. This implies that the migration lesion induced at the level of the cytoskeleton by MFG-E8/MSP68 may be more important in explaining how infiltration is attenuated in sepsis than a decrease in chemotractant sensing. Therefore, strategies involving the inhibition of Rac-1 activation and thus modulation of downstream F-actin formation in neutrophils could serve as effective therapies for inflammation37.

Using dendritic cells, MFG-E8 was shown to promote apoptotic cell engulfment (a cytoskeleton mediated process) through the up-regulation of Crk–DOCK180–Rac1 pathway38. In light of our findings, this suggests that MFG-E8/MSP68 binding can result in varying processes depending on the context. In the setting of apoptosis, its phosphatidyl serine binding capacity allows MFG-E8 to behave as an opsonin linking apoptotic cells to professional phagocytes. MSP68 was constructed based on human MFG-E8’s N-terminal region containing an RGD sequence flanked by two valine residues19. Since MSP68 does not have the C-terminal domain of MFG-E8 which can recognize the phosphatidyl serine of apoptotic cells, it lacks the ability to recognize apoptotic cells to help promote their phagocytosis by macrophages. Thus, the up-regulation of Crk–DOCK180–Rac1 pathway that occurs during the phagocytic process of apoptotic cells may not be related to how MFG-E8 and MSP68 abrogate sepsis induced morbidity and mortality.

Among the earliest observations about the nature of integrin signaling was that in the presence of the integrin ligand fibronectin, the actin cytoskeleton underwent polymerization and this finding was followed by another experiment showing that actin depolymerization led to loss of binding to surface fibronectin39, 40. This bidirectional signaling has ramifications in the context of MSP68 signaling. It provides a framework for understanding how MSP68 binding to integrins on the surface of neutrophils can lead to changes not just in the cytoskeleton, but on the surface adhesion characteristics of neutrophils. Previously, we have shown that neutrophils treated with MSP68 had decreased adhesion capacity19. Taken alone, this supports the notion that MSP68 functions as a competitive inhibitor of integrin ligands, such as fibronectin, laminin and collagen41. In light of our data it is clear that this may be an oversimplification of the role MSP68 is playing. We have found that MSP68 binding leads to inhibition of downstream signaling elements which is consistent with the more specific role of integrin antagonist in the setting of inflammation.

The results of this study animate an ongoing discussion on the role of MAP kinases in sepsis as treatment targets. Activation of p38- and ERK-dependent pathways is associated with splenic, pulmonary, and hepatic inflammation42–44. Endothelial dysfunction and coagulopathy have also been found to be mediated by these pathways42–44. A conceptual challenge of pharmaceutical approaches directed at specific signaling elements is the diversity of signaling molecules that participate in inflammation signaling. Blocking a single player may not abrogate the process as a whole. Our data suggests that MSP68 binding is associated with upregulation of inhibitors of multiple MAPK pathways beyond f-MLP, including CXCR2 and C5a cascades (Data not published).

MSP68 is an important window into the functions of MFG-E8. To date there are no published reports of functions possessed by MFG-E8 that are not shared by MSP68. MFG-E8 has been proposed as a bridging molecule between phagocytes and apoptotic cells15, 16. It is also clear that MFG-E8 works to promote the clearance of apoptotic cells which is beneficial in inflammation14, 45, 46. However, the contribution of the RGD containing domain of MFG-E8 may be very important. Synthetic RGD peptides have garnered interest as potential treatments in acute inflammation. In models of acute lung injury, these constructs have shown the ability to inhibit integrin signaling along MAP kinase pathways47, 48. Other studies have shown that there is a marked decrease in systemic mediators of inflammation with synthetic RGD treatment49. Our findings are consistent with these studies and shed light on the role the cytoskeleton plays in sepsis and inflammation.

In our study, we treated septic animals with MSP68 and then assessed RacI activity in neutrophils isolated from lungs. This may raise the question whether or not the in vivo treatment with MSP68 could induce immunogenic response by producing antibody. The possibility of MSP68-induced immunogenic response can be ruled-out by the fact that MSP68 is a five amino acid containing peptide originally derived from its parent molecule, milk fat globule-EGF-factor VIII (MFG-E8), which is endogenously produced in our body by a wide range of tissues and cells13, 14, 19. The peptide sequence of MSP68 which is derived from the parent MFG-E8 molecule is highly conserved as MFG-E8 contains the RGD motif in its structure. Since MSP68 is essentially the RGD motif/domain of an endogenous molecule, there was no reason to assume it exerts immunogenicity. In line with this, recent in vivo study using RGD peptides have been shown which did not mention its immunogenicity49. Moreover, in our in vivo studies we treated mice with MSP68 for 20 h which is a time point relevant to acute sepsis. The model we used in this study cannot test the adaptive immune system as this is not enough time to mount an adaptive antibody response. We therefore suggest that MSP68 may not generate immunogenicity when injected into animals once in the setting of acute sepsis.

The Rho family of GTPases including Rac, Cdc42, and Rho are enzymes that form the final common pathway for various extracellular signals that induce changes in the cytoskeleton of the cells50. Rac-1 is known to be important for the secretion of chemokines51, 52, chemotaxis53, as well as a number of higher functions in the innate immune system54, 55. A strength of this study is that Rac-1 inhibition was observed in neutrophils at two levels. First, changes in the cytoskeleton are observable in the bone marrow prior to tissue infiltration. Secondly, neutrophil Rac1 signaling was reduced after transmigration in the whole lung. Additionally, migration from the tissue into the air space was also inhibited. Efficacy in multiple tissues suggests that MFG-E8/MSP68 will be a robust therapy for preventing sepsis mediated organ dysfunction in patients.

The in vivo experiments described in this study show that MSP68’s effects on signaling were observable in mouse BMDNs after CLP and that end tissues in turn demonstrated the MSP68 effect: decreased activation of inflammatory signaling. We chose to measure whole lung Rac1 tissue rather than bronchoalveolar lavage Rac1 because both positive and negative results would fail to address our hypothesis if the BAL was assayed. Transmigration from the capillary to airspace compartment would act as a selective barrier, allowing only cells whose inflammatory signaling was intact to pass. By taking the whole lung, we were able to observe both cells that were still able to migrate and those whose migration is affected by MSP68. BAL counts were consistent with the hypothesis that MSP68 reduces infiltration into tissues.

In summary, this study demonstrates that MSP68’s effect on neutrophil migration and sepsis associated morbidity are mediated through the cytoskeleton and Rac1 signaling. MSP68 works as an inhibitor of the integrin signaling associated with inflammation in neutrophils. It is clear that MSP68 and its parent molecule MFG-E8 have the potential to be transformative agents in critical care. This study also points to a new paradigm on the role of the cytoskeleton in inflammation. The challenge going forward will be to translate these compounds into viable candidates for drug trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01GM053008 R01GM057468, R35GM118337 to PW.

List of Abbreviations

- MFG-E8

milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-factor VIII

- MSP68

MFG-E8-derived short peptide 68

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- f-MLP

N-formylmethionine-leucine-phenylalanine

- BMDN

bone marrow-derived neutrophil

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author Contributions

LH, MA, W-LY, MS designed the experiments. LH carried-out the in vivo and in vitro experiments. LH performed data analysis. LH, MA wrote the manuscript. JN, GC, PW reviewed and edited the manuscript. PW conceived the idea and supervised the whole project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(62):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, et al. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler EJ, McCutchan JA, Fierer J, et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and shock with human antiserum to a mutant Escherichia coli. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1225–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211113072001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone RC, Fisher CJ, Jr, Clemmer TP, et al. A controlled clinical trial of high-dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:653–658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709103171101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panacek EA, Marshall JC, Albertson TE, et al. Efficacy and safety of the monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody F(ab’)2 fragment afelimomab in patients with severe sepsis and elevated interleukin-6 levels. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2173–2182. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145229.59014.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aziz M, Jacob A, Yang WL, et al. Current trends in inflammatory and immunomodulatory mediators in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:329–342. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0912437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truwit JD, Bernard GR, et al. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute ARDSClinical Trials Network. Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brocklehurst P, Farrell B, et al. INIS Collaborative Group. Treatment of neonatal sepsis with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1201–1211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Septic shock--evaluating another failed treatment. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2122–2124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1203412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda A, Jacob A, Wu R, et al. Milk fat globule-EGF factor VIII in sepsis and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Med. 2011;17:126–133. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miksa M, Wu R, Dong W, et al. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes containing milk fat globule epidermal growth factor-factor VIII attenuate proinflammatory responses in sepsis. Shock. 2006;25:586–593. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209533.22941.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, et al. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature. 2002;417:182–187. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz M, Jacob A, Matsuda A, et al. Review: milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 expression, function and plausible signal transduction in resolving inflammation. Apoptosis. 2011;16:10771086. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aziz M, Matsuda A, Yang WL, et al. Milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor-factor 8 attenuates neutrophil infiltration in acute lung injury via modulation of CXCR2. J Immunol. 2012;189:393–402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui T, Miksa M, Wu R, et al. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 attenuates acute lung injury in mice after intestinal ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:238–246. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-625OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang WL, Sharma A, Zhang F, et al. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor-factor 8-derived peptide attenuates organ injury and improves survival in sepsis. Crit Care. 2015;19:375015–1094-3. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1094-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagels MA, Hugli TE. Neutrophil chemotactic factors promote leukocytosis. A common mechanism for cellular recruitment from bone marrow. J Immunol. 1992;148:1119–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimasi D, Sun WY, Bonder CS. Neutrophil interactions with the vascular endothelium. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiner OD, Servant G, Welch MD, et al. Spatial control of actin polymerization during neutrophil chemotaxis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:75–81. doi: 10.1038/10042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filippi MD, Szczur K, Harris CE, et al. Rho GTPase Rac1 is critical for neutrophil migration into the lung. Blood. 2007;109:1257–1264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun CX, Downey GP, Zhu F, et al. Rac1 is the small GTPase responsible for regulating the neutrophil chemotaxis compass. Blood. 2004;104:3758–3765. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bokoch GM. Regulation of innate immunity by Rho GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh AL, Sun CX, Zhu F, et al. The role of Rac1 and Rac2 in bacterial killing. Cell Immunol. 2005;235:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainiero F, Soriani A, Strippoli R, et al. RAC1/P38 MAPK signaling pathway controls beta1 integrin-induced interleukin-8 production in human natural killer cells. Immunity. 2000;12:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Ma B, Malik AB, et al. Bidirectional regulation of neutrophil migration by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:457–464. doi: 10.1038/ni.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–S199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Fougerolles AR, Sprague AG, Nickerson-Nutter CL, et al. Regulation of inflammation by collagen-binding integrins alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 in models of hypersensitivity and arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:721–729. doi: 10.1172/JCI7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuenca AG, Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, et al. Cecal ligation and puncture. Chapter 19:Unit 19.13. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1913s91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirano Y, Aziz M, Yang WL, et al. Neutralization of osteopontin attenuates neutrophil migration in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2015;19:53-015-0782-3. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zu YL, Qi J, Gilchrist A, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-alpha or FMLP stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Remick DG. Pathophysiology of sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1435–1444. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alves-Filho JC, Sonego F, Souto FO, et al. Interleukin-33 attenuates sepsis by enhancing neutrophil influx to the site of infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:708–712. doi: 10.1038/nm.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Hoeven D, Gizewski ET, Auchampach JA. Activation of the A(3) adenosine receptor inhibits fMLP-induced Rac activation in mouse bone marrow neutrophils. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1667–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akakura S, Singh S, Spataro M, et al. The opsonin MFG-E8 is a ligand for the alphavbeta5 integrin and triggers DOCK180-dependent Rac1 activation for the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;292:403–416. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali IU, Hynes RO. Effects of cytochalasin B and colchicine on attachment of a major surface protein of fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;471:16–24. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali IU, Mautner V, Lanza R, et al. Restoration of normal morphology, adhesion and cytoskeleton in transformed cells by addition of a transformation-sensitive surface protein. Cell. 1977;11:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowin T, Straub RH. Integrins and their ligands in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:244. doi: 10.1186/ar3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang YJ, Ma XC, Li X. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/nuclear factor-KappaB transduction pathway on coagulation disorders due to endothelial injury induced by sepsis. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2010;22:528–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang Y, Li X, Zhang X, et al. Elevated levels of plasma TNF-alpha are associated with microvascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with sepsis through activating the NF-kappaB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in endothelial cells. Shock. 2014;41:275–281. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu D, Yang X, Xiang Y, et al. Inhibition of Toll-like receptor 9 attenuates sepsis-induced mortality through suppressing excessive inflammatory response. Cell Immunol. 2015;295:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu R, Dong W, Wang Z, et al. Enhancing apoptotic cell clearance mitigates bacterial translocation and promotes tissue repair after gut ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:593–598. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miksa M, Amin D, Wu R, et al. Fractalkine-induced MFG-E8 leads to enhanced apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages. Mol Med. 2007;13:553–560. doi: 10.2119/2007-00019.Miksa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moon C, Han JR, Park HJ, et al. Synthetic RGDS peptide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting integrin signaled MAP kinase pathways. Respir Res. 2009;10:18-9921-10-18. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang B, Wan JY, Zhang L, et al. Synthetic RGDS peptide attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury in rats. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38:204–210. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2012.664835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding X, Wang X, Zhao X, et al. RGD peptides protects against acute lung injury in septic mice through Wisp1-integrin beta6 pathway inhibition. Shock. 2015;43:352–360. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwaiz R, Rahman M, Zhang E, et al. Platelet secretion of CXCL4 is Rac1-dependent and regulates neutrophil infiltration and tissue damage in septic lung damage. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:5347–5359. doi: 10.1111/bph.13325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hwaiz R, Rahman M, Syk I, et al. Rac1-dependent secretion of platelet-derived CCL5 regulates neutrophil recruitment via activation of alveolar macrophages in septic lung injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A1214-603R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doppler H, Bastea LI, Eiseler T, et al. Neuregulin mediates F-actin-driven cell migration through inhibition of protein kinase D1 via Rac1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:455–465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shao M, Tang ST, Liu B, et al. Rac1 mediates HMGB1induced hyperpermeability in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells via MAPK signal transduction. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:529–535. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwaiz R, Hasan Z, Rahman M, et al. Rac1 signaling regulates sepsis-induced pathologic inflammation in the lung via attenuation of Mac-1 expression and CXC chemokine formation. J Surg Res. 2013;183:798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]