Abstract

Introduction

Leukemia is a collection of highly heterogeneous cancers that arise from neoplastic transformation and clonal expansion of immature hematopoietic cells. Post-treatment recurrence is high, especially among elderly patients, thus necessitating more effective treatment modalities. Development of novel anti-leukemic compounds relies heavily on traditional in vitro screens which require extensive resources and time. Therefore, integration of in silico screens prior to experimental validation can improve the efficiency of pre-clinical drug development.

Areas covered

This article reviews different methods and frameworks used to computationally screen for anti-leukemic agents. In particular, three approaches are discussed including molecular docking, transcriptomic integration, and network analysis.

Expert opinion

Today’s data deluge presents novel opportunities to develop computational tools and pipelines to screen for likely therapeutic candidates in the treatment of leukemia. Formal integration of these methodologies can accelerate and improve the efficiency of modern day anti-leukemic drug discovery and ease the economic and healthcare burden associated with it.

Keywords: Computational drug repositioning, molecular docking, transcription profiling, network analysis, leukemia

1. Introduction

Leukemogenesis is initiated through the emergence of neoplastic progenitors during hematopoiesis that subsequently undergo clonal expansion leading to full blown leukemia 1. Leukemia comprises four main subgroups: Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). AML and CML involve the generation of abnormal myelogenous blasts which, in an otherwise properly functional hematopoietic background, would give rise to mature eosinophils, mast cells, neutrophils, and monoctyes/macrophages 2. CML and CLL occur when progenitors belonging to the lymphoid lineage, responsible for the generation of T-cells and B-cells, undergo neoplastic transformation 3. Furthermore, studies have shown that leukemia exhibits stem-like properties possibly due to the activity of cancer stem cells, which is associated with poor prognosis 4–6. Thus, leukemia is a heterogeneous disease that must be combated with precise treatment regimens.

Regardless of the type, leukemia is a debilitating disease that afflicts ∼0.14% of the population in the United States each year, with a 5-year survival rate of 59.7% (AML: 26.6, CML: 65.1%, ALL: 68.1%, CLL: 82.6%) according to epidemiological data from 2006–2012 7. Treatment of leukemia varies depending on subgroup and clinical presentation. Acute leukemia patients are typically treated with three phases of chemotherapy (induction, consolidation, and maintenance), and development of targeted inhibitors and antibody therapeutics are underway 2, 8. In the case of chronic leukemia, patients can be treated with a variety of chemical and antibody targeted inhibitors 9, 10.

The majority of pre-clinical screening procedures involve the use of in vitro and in vivo phenotypic screening techniques such as systematic evaluation of compound efficacy in cell line models of disease 11. However, these screens are expensive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive, making modern pre-clinical drug discovery procedures somewhat anachronistic. To circumvent these issues and improve upon screening pipelines, various in silico techniques have been proposed to rapidly screen for pre-clinical candidate drugs that can be subsequently validated in vitro or in vivo. By adopting this approach, it is possible to filter out unlikely candidates and reduce the number of compounds to test. Thus, in silico screens can ease the economic burden of drug discovery, expedite the identification of novel therapeutic candidates, and repurpose approved drugs for new indications.

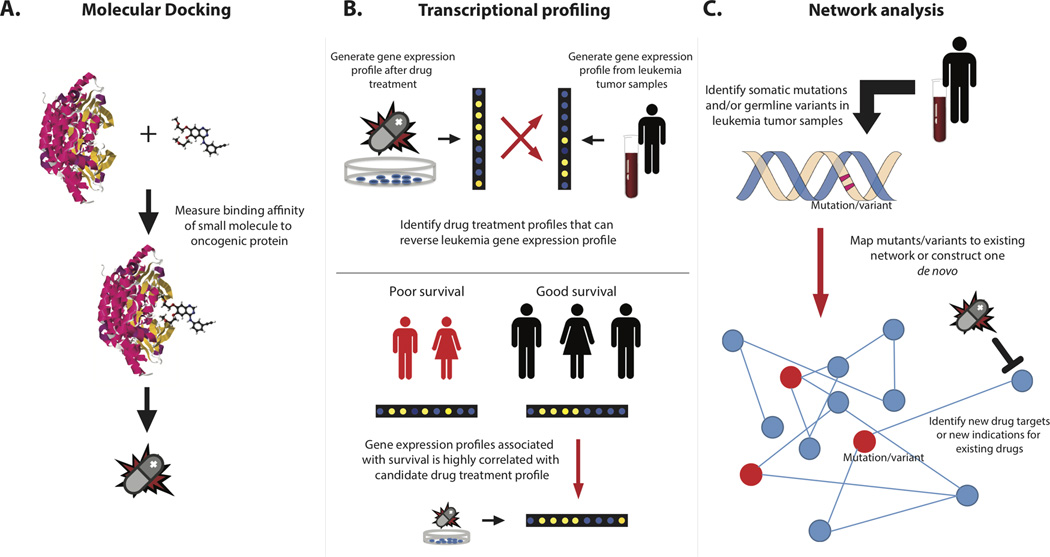

In this review we discuss three different approaches to in silico drug screening for anti-leukemic candidate agents (Fig. 1). First, we will discuss structure-based methods that computationally simulate drug-target interactions to identify potential inhibitors for a particular target. Second, we will provide an overview of transcriptomic-based approaches which integrate drug treatment profiles with disease gene expression profiles to predict novel candidates. Lastly, we will explore the application of network theory for in silico drug screening. We argue that an integration of these approaches into current drug screening schema will be optimal for pinpointing the most likely candidates to be validated in later trials.

Figure 1. Approaches to in silico drug repositioning for leukemia.

A. Molecular docking can be used to screen through millions of small molecules to identify candidates that can target a protein of interest. The drug target must be known a priori. B. Transcriptional profiling of leukemia cells after treatment with a drug can be combined with disease gene expression signatures to identify drug candidates. Drug treatment profiles that can reverse a disease signature are predicted to have a therapeutic effect. Alternatively, gene expression patterns associated with good prognosis and correlate with a drug treatment profile indicate drug efficacy. C. Network analysis can be used to analyze somatic mutations or germline variants at a systems level.

2. Structure-based drug design

In silico drug screening has traditionally involved the use of molecular docking software to assess the binding affinity of a potential drug to a known target. Several computer software programs exist to simulate how the ligand interacts with a protein of interest under equilibrium or imposed conditions by optimizing scoring functions that account for physical and chemical interactions at binding interfaces 12, 13. These approaches have also been utilized to identify drug candidates that target proteins that drive leukemia.

These structure-based drug discovery projects couple information about the target protein structure with large databases of small-molecule chemical structures to rapidly screen for potential drug candidates. Currently the RCSB Protein Data Bank consists of over 100,000 macromolecular structures providing a rich resource for structure-based drug design 14. Furthermore, several databases exist that provide information on thousands of small-molecules that can be systematically screened in silico 15. These resources have been used in several computationally screening pipelines in leukemia.

In one study, Banavath and colleagues screened for potential therapeutics that could target both wild type and T315I mutant BCR-ABL, the latter which drives imatinib resistance in CML 16. They used molecular dynamic simulations to screen a library of 36,481 small molecules downloaded from the Small-molecule Meta-Database17, DrugBank18, and PubChem2319 databases. They then compared the binding affinities of these drugs to known BCR-ABL inhibitors including ponatinib, bosutinib, bafetinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and imatinib. From this screen, they were able to identify 7 top candidates which were further investigated with additional molecular dynamics simulation studies. In this study, the exact crystallographic structure of mutant and wild-type BCR-ABL was available at the time of screening. However, this is not always the case and the target protein structure must be predicted using techniques such as homology modeling, which involves predicting a protein structure by using a known template structure of another related protein 20. Despite not verifying their candidates experimentally, this study provided new drug leads that can be verified in future studies.

As such, Mishra and colleagues took an integrated approach whereby they performed an in silico screen for drugs that could inhibit GLUT4 21. GLUT4, a glucose transporter, has been shown in previous studies to be constitutively expressed in leukemia cells where it mediates glucose uptake. Furthermore, studies have shown that when inactivated, GLUT4 can confer sensitivity to metformin in CLL 21. Due to the lack of a protein structure for GLUT4, the authors first inferred a structure based on shared homology with GlpT (E.Coli glycerol-3-phosphate transporter) and EmrD (E. Coli multidrug resistance protein D). Second, the authors systematically scored 18 million compounds from the ZINC database 22 using a molecular docking procedure. In total, they were able to identify 32 drug candidates in silico and experimentally demonstrated the potency of 2 candidates in multiple myeloma cell lines. These results demonstrate the feasibility of filtering millions of compounds into a small, confident set of compounds that can then be evaluated more carefully.

Liao and colleagues implemented a high-throughput molecular docking screening framework to identify small molecules that inhibit the SH2 domain of stat5a/b, a key effector protein that plays a role in imatinib resistance in CML 23. The structure of SH2 was not known, so they constructed the SH2 domain via homology modeling and screened 30 million small molecules from NCI 24, Maybridge 25, LeadQuest 25, Virtual Chemistry 25, and Drug-Like Compounds 25 databases to identify those that could inhibit stat5b dimerization by binding to sub-pockets located at the dimerization interface. They discovered 30 potential candidates which were biochemically screened for activity yielding a single inhibitor, IST5-002, as the top candidate. Remarkably, they found that the inhibitor was able to suppress BCR-ABL driven CML growth in vitro.

Ke and colleagues used homology modeling to predict the structure of activated (DFG-in) FLT3, a key driver of AML, and carried out a molecular docking to virtually screen an in-house database of 125,000 molecules derived from the ChemDiversity database 26. Subsequently, they were able to identify 97 candidate compounds which were subjected to binding mode analysis, density functional theory analysis, and molecular dynamic simulations which further explore and validate the ability of the drug candidates to inhibit their targets. From this computational screen and further computational analysis, the authors were able to identify two DFG-in FLT3 inhibitor candidates, BPR056 and BPR080.

These studies and several others 27, 28 demonstrate that molecular docking simulations can provide rapid screening of large compound libraries. However, these studies are most effective when the structure of the drug and the target be known a priori. Therefore, identification of the drug target and its structure is the primary downfall of these computational biochemical approaches since the exact protein structure of a target is not always available. To circumvent this issue, previous studies have thus adopted a combined structure prediction and homology modeling methodology to generate a predicted structure. Furthermore, molecular docking must be accompanied by molecular dynamic simulations to enhance precision. Overall, molecular docking simulations provide a valuable tool to rapidly screen drug compound libraries for the most likely candidates.

In addition to molecular docking, ligand-based drug design has also been used to identify new drugs for the treatment of leukemia. This approach involves quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) modeling which identifies physiochemical properties that contribute to a drug’s effectiveness. 29 As such, the target structure of the drug is not required because the structural features of a drug are analyzed after verifying that it possesses pharmacological activity. To highlight a few studies, Arthur and colleagues were able to identify key chemical features that contribute to the anti-cancer effects of 112 compounds in MOLT-4 and P388 leukemia cell lines 30. In addition, Katritzky and colleagues screened 34 compounds against RBMI-8226 cell lines to guide their synthesis of 5 bis-urea containing-compounds of which they tested in various cancer cell lines 31. Ultimately, ligand-based drug design provides an alternative to molecular docking studies in the case where the drug target structure is unknown or cannot be accurately predicted.

3. Transcriptomic-based approaches

Gene expression data has recently become easily accessible as a result of DNA microarray and RNA-seq technologies. These data are derived from diverse biological contexts and can be used to infer changes in gene regulation induced by specific external or internal perturbations. Under a controlled experimental setting, it is possible to generate “transcriptomic signatures” by comparing case and control gene expression profiles. These resulting signatures encode changes in gene expression induced by a particular stimuli and can be used in downstream genomic analyses.

The central goal behind transcriptomic-based screening is to determine whether a drug can down-regulate genes up-regulated in a disease, and conversely, up-regulate genes down-regulated in a disease. If this is the case, then treatment with the drug will presumably reverse the change in gene expression caused by the disease and thus exert a therapeutic effect. Therefore, it is possible to determine the effects a drug will have on genes in a specific disease context by treating cultured cell lines with the drug and interrogating changes in gene expression with DNA microarray or RNA-seq. These profiles are then combined with gene expression profiles derived from leukemia patients to determine if the drug profile is anti-correlated with the disease profile.

3.1 Drug treatment gene expression compendia

Several databases exist that provide comprehensive libraries of gene expression profiles generated from drug treatment experiments. Among the most popular is the Connectivity Map (CMap) which provides gene expression profiles for approximately 6000 different drugs 32. Furthermore, these drug treatment experiments were performed in MCF7 (breast), HL60 (blood), and PC3 (prostate) cancer cell lines. The availability of drug treatment profiles in three tissue types provide researchers with the flexibility of using drug treatment profiles that are derived from tissue that match that of their disease of interest. When integrating biological data from diverse sources, it is generally good practice to match them based on tissue type to avoid noise mainly caused by tissue differences. Thus, CMAP is best used for cancers of the breast, blood, and prostate. Another comprehensive database is the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) which provides baseline gene expression profiles and drug sensitivity information for more than 1000 cell lines of different tissue origin 33. Among these cell lines, more than 100 were derived from hematopoietic cells at different developmental stages. In addition to these databases, several drug treatment gene expression datasets from small-scale studies are readily available from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

3.2 Common techniques for comparing gene expression profiles

Several techniques have been developed to compare two gene expression profiles. Most simply, similarity between two profiles can be computed via Pearson or Spearman correlation. Another approach is to define differentially regulated genes in one profile and test if they are enriched in differentially expressed genes in a second profile. A more sophisticated approach involves using Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like testing procedures, such as Gene Set Enrichment Analysis24 or BASE 34, 35, which compare the distribution of differential expressed genes between two profiles. Several studies have utilized these methods to develop computational screening pipelines for leukemia.

3.3 In silico screening using transcriptomic profiles

Glucocorticoids such as prednisolone and dexamethasone remain important components of ALL treatment and resistance to these therapeutics is associated with poor survival 36. In a high profile study, Wei and colleagues adopted an in silico strategy to screen for drug compounds that could induce glucocorticoid sensitivity in ALL cell lines 37. They first generated a signature of glucocorticoid resistance by comparing the gene expression signature of glucocorticoid-resistant and glucocorticoid-sensitive patient ALL samples taken prior to therapy. They then screened for drug compounds that could induce a sensitive-like signature by interrogating the CMap. They found that the sirolimus (rapamycin) drug signature, was significantly associated with glucocorticoid sensitivity in that it could induce changes in expression in genes that were differentially expressed between glucocorticoid-resistant and sensitive cell lines. This association was calculated using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test which evaluates whether there is a non-uniform distribution of drug signature genes in the up- or down-regulated genes between resistant and sensitive samples. After computational identification of sirolimus, they were able to experimentally demonstrate that ALL cells treated with sirolimus could induce glucocorticoid sensitivity in Akt-induced glucocorticoid resistant mouse T-hybridoma 2B4 cell lines.

In another approach, Hassane and colleagues hypothesized that the transcriptomic signature of parthenolide, a known AML therapeutic, could be used to computationally search for drugs with similar efficacy by comparing their transcriptomic signatures 38. Their approach involved microarray hybridization of 12 primary CD34+ AML tumor samples cultured ex vivo with and without parthenolide. Differentially expressed genes between parthenolide-treated and untreated samples were used to generate a transcriptomic signature of parthenolide treatment. They then mined the Gene Expression Omnibus database for transcriptomic signatures corresponding to several drugs and systematically compared them to the parthenolide signature using a partial correlation procedure. From this gene expression-based in silico screen of potential anti-AML candidates, they were able to identify celastrol and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal as top hits. These compounds were then further shown to inhibit colony growth of primary CD34+ AML cells in vitro. In a later study, Hassane and colleagues performed a computational screen for compounds that synergized with parthenolide by comparing the parthenolide signature with signatures from the CMap database 39. They reasoned that drug signatures that counteracted the cytoprotective pathways induced by parthenolide would enhance the its treatment efficacy. From this screen, they identified wortmannin, sirolimus, and LY294002 (inhibitors of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway) as potential synergistic effectors and further validated the combinatorial therapy in primary AML cel lines. Furthermore, they were able to demonstrate the ability of temsirolimus (a derivative of sirolimus) in reducing tumor burden in AML-xenotransplanted NOD/SCID mice.

As a proof of concept, Marstrand and colleagues screened for drug candidates to treat Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL), the M3 subtype of AML, by using two transcriptomic signatures corresponding to all-trans-retinoic-acid (ATRA) treatment and stemness 40. ATRA is commonly used in APL patients to induce remission and is highly effective when combined with anthracycline-based chemotherapy 41–43. However, a subset of patients (10–30%) will experience disease recurrence within 5 years despite treatment 43. Therefore, Marstrand et al. designed an in silico framework to screen for drugs that exhibited activity similar to ATRA. They first generated a ATRA transcriptomic signature by comparing the gene expression profiles between ATRA-treated APL (5 days) with untreated APL. Additionally, they rationed that a drug that could target the same genes as ATRA while reversing gene expression associated with stemness would be most efficacious. As such they generated a stemness signature by comparing gene expression profiles between hematopoietic stem cells with hematopoietic progenitor cells. They then utilized the CMap database to screen for drugs that could induce a gene expression signature in HL60 cell lines that closely mirrored that of ATRA and that anti-correlated with the stemness signature. They identified three candidate compounds including Trichostatin A (histone deacetylase inhibitor), LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), and Quinacrine (phospholipase A2 inhibitor) and showed that they could inhibit the growth of PML-derived NB4 cell lines.

In a pan-cancer analysis, Shigemizu and colleagues developed an approach that used variable gene signatures instead of fixed signatures that were implemented by the previously mentioned studies 44. Typically, gene expression signatures of a disease are generated by taking the top n differentially expressed genes in a profile based on some statistical threshold such as p-value or fold change. Shigemizu et al. argued that using a more dynamic approach to define signatures would yield more reliable results. Specifically, they defined gene expression disease signatures in leukemia, breast, and prostate cancer by comparing primary tumor samples with unmatched normal tissue. They then set different thresholds to generate a library of disease signatures containing k number of up-regulated and down-regulated genes for each disease profile. They then repeated this procedure using drug treatment gene expression profiles from the CMap database 32. They then calculated the overlap between the up-regulated k genes in the disease signature to the down-regulated k genes in the drug treatment signature, and similarly the overlap between the down-regulated k genes in the disease signature to the up-regulated k genes in the drug treatment signature. They performed this analysis systematically at different k thresholds to search for potential drug candidates. Finally, the optimal k was chosen based on how many of the predicted drugs also overlapped with known drugs approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA). By using this dynamic approach, the authors were able to identify 115 drug candidates for AML with 52 them being previously FDA-approved.

3.4 Incorporating clinical information to guide screening

As an extension of these approaches, Ung and colleagues developed an in silico screening framework based on the hypothesis that a drug’s effectiveness can be evaluated based on whether it could modulate genes associated with patient survival 45, 46. Importantly, the approach taken by Ung et al. utilized an algorithm that incorporated the entire disease and drug treatment profiles without setting thresholds to define gene signatures. Comparisons between disease profiles and drug treatment profiles were implemented using a weighted running sum statistic calculated across entire gene expression profiles. This method essentially removed the requirement to set arbitrary thresholds that extract only a portion of genes within profiles. To carry out this framework, the authors applied CMap drug transcriptomic profiles to interrogate AML patient gene expression compendia by calculating a Drug Regulatory Score (DRS) for each patient 45. The score was calculated using the BASE algorithm 35 and represents a quantitative measurement of how similar each AML patient’s gene expression profile was to each CMap drug treatment profile 32. The DRS for each drug was then used as the independent variable in a univariate Cox proportional hazards model to determine if it was significantly associated with patient survival. If patients with good prognosis tend to express a gene expression pattern similar to that induced by a drug, then that drug is considered a potential a candidate. They were able to identify several drugs including sulfasalazine, fluoxetine, clozapine, and betulinic acid as candidates and found that these specific drugs reduced tumor growth in mice with AML xenografts. This approach differs conceptually from previous approaches in that it does not search for a drug that can potentially reverse a disease’s gene expression pattern. Instead, it evaluates whether patients that exhibit a “natural” form of the drug in terms of gene expression tend to survive longer. As such, this concept allowed the authors to integrate clinical information into the analysis.

3.5 Limitations

Studies using drug transcriptomic profiles have introduced new avenues for in silico drug screening but still suffer from several downfalls. First, these profiles capture the transcriptomic state that corresponds to a single point in time at a single given dose. Indeed, the effect of a drug on gene expression may vary as a function of time and dose making it difficult to capture the drug’s optimal effect. Secondly, the cell lines from which the profiles are derived from may affect the overall gene expression profile output. Thus, comparing profiles generated from different genetic backgrounds may not always provide an accurate prediction of drug effect. In spite of these issues, transcriptomic-based approaches can provide a screening framework that can filter out the most unlikely candidates before further experimental testing.

4. Application of network theory for drug screening

Network theory has contributed significantly to mapping the relationships between drugs and drug targets. Several types of biological networks exist including protein-protein interaction, regulatory, metabolic, and functional interaction networks 47, 48. By applying network-based methods, it is possible to study key biomolecules (nodes) and their interactions (edges) in the context of a larger biological system. A key assumption behind biological networks is that bio-molecules which tend to lie close to each other in terms of network space are more likely to be involved in similar biological processes 47, 49. This concept of network distance is termed path length and can be calculated using algorithms that count the number of “walks” between two nodes. Furthermore, bio-molecules that tend to have more interactions (degree) or lie within the paths of other interacting bio-molecules (betweenness) tend to exhibit greater importance in maintaining the functionality of the system 47.

4.1 Network analyses of GWAS data

These systems’ level approach can also be applied in leukemia research to computationally identify novel drug targets and existing drugs that exhibit anti-leukemia properties. In the case of leukemia, networks have mostly been applied to study germline and somatic variants discovered through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and next-generation sequencing of tumor genomes, respectively. Among the most popular approaches are mapping identified variants to existing biological networks to study their topological characteristics and constructing drug-mutation networks de novo.

The earliest attempts to characterize genetic associations with disease risk in a high-throughput fashion involved GWAS, which aimed to identify germline variants that were associated with increased susceptibility to a disease of interest. Initially, these disease-associated variants were presumed to be causal drivers of the disease. However, many of these variants happened to be merely proxies for true causal variants due to linkage disequilibrium. Furthermore, these variants were typically analyzed out of the context of a greater genetic interaction framework and thus exhibited small effect sizes when considered as a single variable 50. Despite these limitations, integration of GWAS data can help inform researchers of potential drug targets that can then be cross-referenced to drug-target databases such as DrugBank18, PharmGKB51, and DGIdb52 to identify new therapeutic candidates. In the case of leukemia, several GWASs have been performed and have identified a number of risk loci for AML 53, CML 54, ALL 55, 56, and CLL 57, 58.

To utilize these data for computational drug repositioning, Cao and colleagues adopted a network based approach that integrated these GWAS data to identify novel drug targets for several diseases including ALL 59. They hypothesized that potential drug targets would lie in close vicinity to gene products known to contain disease-associated variants in the context of a functional interaction network. Indeed, they found that known drug targets were enriched in the first-order neighbors of gene products that contained known disease-associated variants. These results suggest that germline variants may not be the causal drivers of the disease but may interact with them at a functional level. Furthermore, they implemented several machine learning approaches including support vector machines, naïve Bayes, and random forest classifiers to predict drug targets using the common neighbor metric as a predictor. Intuitively, this analysis can be extended to identify novel proteins involved in leukemia development where there may already exist drugs that can target them. Currently, functional annotation of variants identified through GWASs are underway which may yield new insight into how these data can assist in developing computational drug screens.

4.2 Network analysis of somatic mutations identified through next-generation sequencing

In addition to GWAS, high-throughput sequencing of leukemia genomes from primary patient biopsies have yielded substantial biological insight into potential somatic driver mutations that initiate leukemogenesis and drive cancer progression 60–62. Many of these somatic variants are potential drug targets and can be used to screen for new compounds that inactivate them. Furthermore, combining this information with existing publically-available drug-target networks or transcriptomic data can provide a powerful and efficient way to systematically search for new anti-leukemic compounds.

In another study focusing on somatic mutations, Cheng and colleagues developed an integrative network-based screening approach that combined drug treatment transcriptomic profiles with catalogued somatically mutated genes identified across 29 different cancer types including AML, CLL, and ALL 63. By utilizing CMap drug transcriptomic profiles, they rationalized that somatically mutated genes identified across several cancers could potentially be targeted by a drug if it was among the top differentially expressed genes in the CMap drug profile 32. They also considered a drug to be a potential candidate if the differentially expressed genes in its transcriptomic profile happened to be vicinal to somatic mutants in the context of a protein-protein interaction network. By identifying which somatic variants and its neighboring proteins were in which drug treatment profiles’ differentially expressed genes, they were able to construct a drug-target network which could be used to identify a large number of drug candidates for a patient sample based on its mutational repertoire.

Several of these network-based studies utilized undirected networks which do not provide information about proteins upstream or downstream of somatic mutations or germline variants. This information is important especially in the design of targeted therapies where the aim is to shut down a signaling pathway that is driven by a particular oncoprotein. Presumably, targeting proteins downstream of cancer drivers may be more effective in blocking propagation of proliferation and survival signals. Furthermore, these network-based studies have focused on either germline variants or somatic mutations. To address these limitations, Ung and colleagues performed a systematic pan-cancer analysis of cancer-related somatic mutations, germline variants, and drug targets in the context of a directed functional interaction network. By taking into account directionality, they found that there existed an intrinsic hierarchy between genes that were targeted by drugs and those that were found to harbor mutations or germline variants. In particular, the authors found that drug target genes tended to lie upstream of genes with identified somatic mutations and germline variants 64.

4.3 Limitations

Network analysis can enable analysis of biological systems from a global view but suffers from several limitations. First, most biological networks are constructed from experimental data and remain incomplete. This introduces uncertainty about the conclusions that can be drawn from network-based analyses. Despite incompleteness, it is still possible to extract biological insight from these networks if it is known that knowledge about a particular biological process is saturated 65. Second, ascertainment bias is also a major issue such that more popular biological phenomena will be overrepresented in biological networks. As a result, some studies implement permutation based methods to mitigate bias inherent in biological networks 66, 67. Third, leukemia has been known to harbor relatively few mutations compared to other cancers, putting into question the utility of network-based drug repositioning approaches for leukemia 68.

5. Integrative Analysis

The recent explosion of biological and genomic data presents novel opportunities to integrate this variety of computational screening approaches to analyze more complex datasets. Several large-scale consortia-led projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have generated tumor multi-omics data comprising of gene expression, sequencing, protein expression, copy number variation, and DNA methylation information for 33 cancer types 69. As such, integrating molecular docking, transcriptomic analysis, and network theory can take advantage of the multifaceted data that are being generated. Furthermore, combining clinical and epidemiological data from leukemia patients can validate and even generate novel hypotheses about potential novel therapeutics. Overall, integration of data and tools is essential for designing in silico drug screening pipelines that can make the most use of the available data.

6. Conclusion

Several in silico approaches exist to systematically screen large libraries of small molecules to identify new therapeutic candidates for the treatment of leukemia. In this review we have provided an overview of the different methods used for computational drug screening. Evidently, the power of each approach is heavily dependent on the types of data that are available. Molecular docking studies utilize structural information on compounds and drug targets to compute their binding affinities. Transcriptomic approaches take advantage of the vast amounts of gene expression data available in the public domain derived from both drug treatment experiments in cell lines and tumor biopsies. Finally, network-based approaches are well suited to analyzing mutation information generated from GWAS and next-generation sequencing projects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of in silico drug repositioning approaches

| Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Identified Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking |

|

|

|

|

Transcriptomic profile analysis |

|

|

Sirolimus39, Wortmannin39, LY29400239, 40, Trichostatin A40, 45, Quinacrine40 |

| Network analysis |

|

|

In addition, there are limitations associated with the application of each method. For molecular docking studies, structural information about the drug and the drug target is required. In the case where the protein structure is not known, structure prediction from amino acid sequence and homology modeling is used to create predicted structures. Of course, this introduces error into the screening procedure if the predicted drug target structure deviates substantially from the true structure. When applying transcriptomic approaches, gene expression information corresponding to drug treatment is required. In most cases, these gene expression profiles are derived from a single dose and at a single time point which may not be representative of a drug’s true effect. Network based approaches also suffer from several issues including selection bias, where biomolecules tend to hold greater importance in a network due to the fact that it has been studied more extensively in the research community. Furthermore, biological networks are typically incomplete and using them can lead to false conclusions due to missing information (Table 1).

Despite these limitations, in silico drug screening has yielded several novel candidates, many of which have been experimentally validated. These approaches have the potential to drastically decrease the number of compounds that need to be screened experimentally. As a result, integration of these computational screening approaches into pre-clinical studies can accelerate lead compound identification and bring down costs associated with experimental validation.

7. Expert Opinion

In today’s data deluge, large-scale data has become increasingly accessible making systematic in silico screening projects for anti-leukemic agents a reality. Several databases and tools exist that facilitate rapid analyses in a relatively short period of time. Furthermore, several studies that have implemented a variety of different approaches and data types have yielded promising results. As more data becomes available, current in silico screening frameworks can further be optimized and improved upon. As one can imagine, this has several implications for modern drug discovery. First, integrating bioinformatics procedures into drug discovery pipelines will allow researchers to rapidly filter out unlikely candidates and single out those that exhibit promising therapeutic properties. By decreasing the number of compounds to experimentally test, drug discovery can proceed more efficiently in terms of both time and cost. Second, many of the approaches used in screening compound libraries can be applied to repurpose drugs that have already been approved for use in the clinic. Re-purposing is advantageous in that the approval process for assigning an existing drug for a new indication is expedited compared to obtaining approval for a completely new drug. Third, in silico screening procedures can lower the barrier of entry to drug development and allow smaller academic laboratories to develop novel therapeutics without the need to hire large teams.

As more data becomes available, especially in the field of genomics, in silico approaches will become an integral part of drug discovery pipelines. In addition, more sophisticated algorithms will need to be developed to deal with new, and increasingly complex datasets. Currently, we argue that utilization of all three in silico approaches (structure-based, transcriptomic, network theoretic) is essential for maximal benefit and should be chosen based on the availability of the data required to implement them. For instance, network based methods can help identify novel drug targets whose structures can be used to screen for therapeutic candidates via molecular docking procedures. Transcriptomic approaches can then be applied to predict drug effect in patient tumors and dissect the functional effects of drug treatment.

Another area of interest is the application of in silico methods to not only identify new therapeutic agents, but tailoring therapies to individuals based on the genomic makeup of their tumors. This idea of precision medicine has widespread implications in oncology since every patient’s tumor harbors different genomic aberrations that cause varied responses to the same drugs. Because genomic technologies such as sequencing becomes exponentially less expensive, genomic interrogation of a patient’s tumor prior to treatment is becoming a reality. As such, this will produce massive amounts of data that can only be analyzed via computational approaches to derive any actionable insight. Thus, in the future, the limiting factor in precision medicine is developing novel computational frameworks and algorithms to dissect a patient’s tumor genome and being able to interpret the results to inform clinicians of the best possible treatment regimen. In summary, computational screening of small-molecule therapeutics has the potential to introduce new avenues in drug discovery and ease the economic and healthcare burden associated with it.

Article Highlights.

Molecular docking, transcriptomic profiling, and network analysis have been applied to computationally screen for novel anti-leukemia drugs.

Molecular docking studies allow researchers to screen through millions of small-molecules given that a drug target is known.

Transcriptomic profiling compares drug treatment gene expression profiles with disease profiles to identify novel candidates without requiring knowledge of the drug targets.

Network analysis of somatic and germline variants in leukemia can identify novel drug targets

Integration of these approaches into drug discovery pipelines can increase the efficiency of the drug screening process

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by American Cancer Society Research grant #IRG-82-003-30, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2TR001088, the start-up funding package provided to C Cheng by the Geisel School of Medicine from Dartmouth College and the Rosaline Borison Memorial Pre-doctoral fellowship provided to MH Ung.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, Miller CA, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, Wartman LD, Lamprecht TL, Liu F, Xia J, Kandoth C, Fulton RS, McLellan MD, Dooling DJ, Wallis JW, Chen K, Harris CC, Schmidt HK, Kalicki-Veizer JM, Lu C, Zhang Q, Lin L, O’Laughlin MD, McMichael JF, Delehaunty KD, Fulton LA, Magrini VJ, McGrath SD, Demeter RT, Vickery TL, Hundal J, Cook LL, Swift GW, Reed JP, Alldredge PA, Wylie TN, Walker JR, Watson MA, Heath SE, Shannon WD, Varghese N, Nagarajan R, Payton JE, Baty JD, Kulkarni S, Klco JM, Tomasson MH, Westervelt P, Walter MJ, Graubert TA, DiPersio JF, Ding L, Mardis ER, Wilson RK. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012 Jul 20;150(2):264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khwaja A, Bjorkholm M, Gale RE, Levine RL, Jordan CT, Ehninger G, Bloomfield CD, Estey E, Burnett A, Cornelissen JJ, Scheinberg DA, Bouscary D, Linch DC. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16010. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008 Feb 22;132(4):631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huntly BJ, Gilliland DG. Leukaemia stem cells and the evolution of cancer-stem-cell research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005 Apr;5(4):311–321. doi: 10.1038/nrc1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eppert K, Takenaka K, Lechman ER, Waldron L, Nilsson B, van Galen P, Metzeler KH, Poeppl A, Ling V, Beyene J, Canty AJ, Danska JS, Bohlander SK, Buske C, Minden MD, Golub TR, Jurisica I, Ebert BL, Dick JE. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nat Med. 2011 Sep;17(9):1086–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varn FS, Andrews EH, Cheng C. Systematic analysis of hematopoietic gene expression profiles for prognostic prediction in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16987. doi: 10.1038/srep16987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/, based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 17;373(12):1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2015 May;90(5):446–460. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woyach JA, Johnson AJ. Targeted therapies in CLL: mechanisms of resistance and strategies for management. Blood. 2015 Jul 23;126(4):471–477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-585075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin G, Wong ST. Toward better drug repositioning: prioritizing and integrating existing methods into efficient pipelines. Drug Discov Today. 2014 May;19(5):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitchen DB, Decornez H, Furr JR, Bajorath J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Nov;3(11):935–949. doi: 10.1038/nrd1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng XY, Zhang HX, Mezei M, Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011 Jun;7(2):146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guha R, Nguyen DT, Southall N, Jadhav A. Dealing with the Data Deluge: Handling the Multitude Of Chemical Biology Data Sources. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2012 Sep;4:193–209. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch110262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banavath HN, Sharma OP, Kumar MS, Baskaran R. Identification of novel tyrosine kinase inhibitors for drug resistant T315I mutant BCR-ABL: a virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulations study. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6948. doi: 10.1038/srep06948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Grotthuss M, Koczyk G, Pas J, Wyrwicz LS, Rychlewski L. Ligand.Info small-molecule Meta-Database. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2004 Dec;7(8):757–761. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law V, Knox C, Djoumbou Y, Jewison T, Guo AC, Liu Y, Maciejewski A, Arndt D, Wilson M, Neveu V, Tang A, Gabriel G, Ly C, Adamjee S, Dame ZT, Han B, Zhou Y, Wishart DS. DrugBank 4.0: shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jan;42(Database issue):D1091–D1097. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A, Han L, He J, He S, Shoemaker BA, Wang J, Yu B, Zhang J, Bryant SH. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jan 4;44(D1):D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavasotto CN, Phatak SS. Homology modeling in drug discovery: current trends and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2009 Jul;14(13–14):676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mishra RK, Wei C, Hresko RC, Bajpai R, Heitmeier M, Matulis SM, Nooka AK, Rosen ST, Hruz PW, Schiltz GE, Shanmugam M. In Silico Modeling-based Identification of Glucose Transporter 4 (GLUT4)-selective Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy. J Biol Chem. 2015 Jun 5;290(23):14441–14453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.628826. Experimentally validated their predictions

- 22.Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J Chem Inf Model. 2012 Jul 23;52(7):1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liao Z, Gu L, Vergalli J, Mariani SA, De Dominici M, Lokareddy RK, Dagvadorj A, Purushottamachar P, McCue PA, Trabulsi E, Lallas CD, Gupta S, Ellsworth E, Blackmon S, Ertel A, Fortina P, Leiby B, Xia G, Rui H, Hoang DT, Gomella LG, Cingolani G, Njar V, Pattabiraman N, Calabretta B, Nevalainen MT. Structure-Based Screen Identifies a Potent Small Molecule Inhibitor of Stat5a/b with Therapeutic Potential for Prostate Cancer and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015 Aug;14(8):1777–1793. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0883. Experimentally validated their predictions

- 24.Monga M, Sausville EA. Developmental therapeutics program at the NCI: molecular target and drug discovery process. Leukemia. 2002 Apr;16(4):520–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ChemNavigator. http://www.chemnavigator.com/

- 26.Ke YY, Singh VK, Coumar MS, Hsu YC, Wang WC, Song JS, Chen CH, Lin WH, Wu SH, Hsu JT, Shih C, Hsieh HP. Homology modeling of DFG-in FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and structure-based virtual screening for inhibitor identification. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11702. doi: 10.1038/srep11702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen S, Li L, Chen Y, Hu J, Liu J, Liu YC, Liu R, Zhang Y, Meng F, Zhu K, Lu J, Zheng M, Chen K, Zhang J, Jiang H, Yao Z, Luo C. Identification of Novel Disruptor of Telomeric Silencing 1-like (DOT1L) Inhibitors through Structure-Based Virtual Screening and Biological Assays. J Chem Inf Model. 2016 Mar 28;56(3):527–534. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar H, Raj U, Srivastava S, Gupta S, Varadwaj PK. Identification of Dual Natural Inhibitors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia by Virtual Screening, Molecular Dynamics Simulation and ADMET Analysis. Interdiscip Sci. 2015 Aug 22; doi: 10.1007/s12539-015-0118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acharya C, Coop A, Polli JE, Mackerell AD., Jr Recent advances in ligand-based drug design: relevance and utility of the conformationally sampled pharmacophore approach. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011 Mar;7(1):10–22. doi: 10.2174/157340911793743547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arthur DE, Uzairu A, Mamza P, Abechi S. Quantitative structure–activity relationship study on potent anticancer compounds against MOLT-4 and P388 leukemia cell lines. J Adv Res. 2016;7(5):823–837. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katritzky AR, Girgis AS, Slavov S, Tala SR, Stoyanova-Slavova I. QSAR modeling, synthesis and bioassay of diverse leukemia RPMI-8226 cell line active agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2010 Nov;45(11):5183–5199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, Reich M, Hieronymus H, Wei G, Armstrong SA, Haggarty SJ, Clemons PA, Wei R, Carr SA, Lander ES, Golub TR. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006 Sep 29;313(5795):1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. Extremely valuable resource containing drug treatment transcriptomic profiles for thousands of drugs in three different cell lines

- 33.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ, Lightfoot H, Forbes S, Bindal N, Beare D, Smith JA, Thompson IR, Ramaswamy S, Futreal PA, Haber DA, Stratton MR, Benes C, McDermott U, Garnett MJ. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Jan;41(Database issue):D955–D961. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 25;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng C, Yan X, Sun F, Li LM. Inferring activity changes of transcription factors by binding association with sorted expression profiles. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:452. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba H, Pui CH. Glucocorticoid use in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2010 Nov;11(11):1096–1106. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wei G, Twomey D, Lamb J, Schlis K, Agarwal J, Stam RW, Opferman JT, Sallan SE, den Boer ML, Pieters R, Golub TR, Armstrong SA. Gene expression-based chemical genomics identifies rapamycin as a modulator of MCL1 and glucocorticoid resistance. Cancer Cell. 2006 Oct;10(4):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.006. Introduced the idea of apply chemical genomics to identify new anti-leukemic drugs

- 38. Hassane DC, Guzman ML, Corbett C, Li X, Abboud R, Young F, Liesveld JL, Carroll M, Jordan CT. Discovery of agents that eradicate leukemia stem cells using an in silico screen of public gene expression data. Blood. 2008 Jun 15;111(12):5654–5662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126003. First systematic and comprehensive screen for anti-leukemic drugs using publicly available datasets

- 39.Hassane DC, Sen S, Minhajuddin M, Rossi RM, Corbett CA, Balys M, Wei L, Crooks PA, Guzman ML, Jordan CT. Chemical genomic screening reveals synergism between parthenolide and inhibitors of the PI-3 kinase and mTOR pathways. Blood. 2010 Dec 23;116(26):5983–5990. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marstrand TT, Borup R, Willer A, Borregaard N, Sandelin A, Porse BT, Theilgaard-Monch K. A conceptual framework for the identification of candidate drugs and drug targets in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010 Jul;24(7):1265–1275. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Degos L, Wang ZY. All trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene. 2001 Oct 29;20(49):7140–7145. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang ME, Ye YC, Chen SR, Chai JR, Lu JX, Zhoa L, Gu LJ, Wang ZY. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988 Aug;72(2):567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang ZY, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2505–2515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shigemizu D, Hu Z, Hung JH, Huang CL, Wang Y, DeLisi C. Using functional signatures to identify repositioned drugs for breast, myelogenous leukemia and prostate cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012 Feb;8(2):e1002347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ung MH, Sun CH, Weng CW, Huang CC, Lin CC, Liu CC, Cheng C. Integrated Drug Expression Analysis for leukemia: an integrated in silico and in vivo approach to drug discovery. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016 Mar 15; doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.18. First study to integrate clinical information into the drug screening procedure in acute myeloid leukemia

- 46.Ung MH, Varn FS, Cheng C. IDEA: Integrated Drug Expression Analysis-Integration of Gene Expression and Clinical Data for the Identification of Therapeutic Candidates. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2015 Jul;4(7):415–425. doi: 10.1002/psp4.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004 Feb;5(2):101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu X, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Getting connected: analysis and principles of biological networks. Genes Dev. 2007 May 1;21(9):1010–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.1528707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitra K, Carvunis AR, Ramesh SK, Ideker T. Integrative approaches for finding modular structure in biological networks. Nat Rev Genet. 2013 Oct;14(10):719–732. doi: 10.1038/nrg3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penrod NM, Cowper-Sal-lari R, Moore JH. Systems genetics for drug target discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011 Oct;32(10):623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hewett M, Oliver DE, Rubin DL, Easton KL, Stuart JM, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenetics Knowledge Base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002 Jan 1;30(1):163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griffith M, Griffith OL, Coffman AC, Weible JV, McMichael JF, Spies NC, Koval J, Das I, Callaway MB, Eldred JM, Miller CA, Subramanian J, Govindan R, Kumar RD, Bose R, Ding L, Walker JR, Larson DE, Dooling DJ, Smith SM, Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Wilson RK. DGIdb: mining the druggable genome. Nat Methods. 2013 Dec;10(12):1209–1210. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knight JA, Skol AD, Shinde A, Hastings D, Walgren RA, Shao J, Tennant TR, Banerjee M, Allan JM, Le Beau MM, Larson RA, Graubert TA, Cox NJ, Onel K. Genome-wide association study to identify novel loci associated with therapy-related myeloid leukemia susceptibility. Blood. 2009 May 28;113(22):5575–5582. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim DH, Lee ST, Won HH, Kim S, Kim MJ, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Kim JW, Kim HJ, Kim YK, Sohn SK, Moon JH, Jung CW, Lipton JH. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with susceptibility to chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011 Jun 23;117(25):6906–6911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Andreu V, Roberts KG, Xu H, Smith C, Zhang H, Yang W, Harvey RC, Payne-Turner D, Devidas M, Cheng IM, Carroll WL, Heerema NA, Carroll AJ, Raetz EA, Gastier-Foster JM, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD, Mrozek K, Kohlschmidt J, Stock W, Kornblau SM, Konopleva M, Paietta E, Rowe JM, Luger SM, Tallman MS, Dean M, Burchard EG, Torgerson DG, Yue F, Wang Y, Pui CH, Jeha S, Relling MV, Evans WE, Gerhard DS, Loh ML, Willman CL, Hunger SP, Mullighan CG, Yang JJ. A genome-wide association study of susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Blood. 2015 Jan 22;125(4):680–686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-595744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu C, Yang W, Devidas M, Cheng C, Pei D, Smith C, Carroll WL, Raetz EA, Bowman WP, Larsen EC, Maloney KW, Martin PL, Mattano LA, Jr, Winick NJ, Mardis ER, Fulton RS, Bhojwani D, Howard SC, Jeha S, Pui CH, Hunger SP, Evans WE, Loh ML, Relling MV. Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Acute Pancreatitis in Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun 20;34(18):2133–2140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Speedy HE, Di Bernardo MC, Sava GP, Dyer MJ, Holroyd A, Wang Y, Sunter NJ, Mansouri L, Juliusson G, Smedby KE, Roos G, Jayne S, Majid A, Dearden C, Hall AG, Mainou-Fowler T, Jackson GH, Summerfield G, Harris RJ, Pettitt AR, Allsup DJ, Bailey JR, Pratt G, Pepper C, Fegan C, Rosenquist R, Catovsky D, Allan JM, Houlston RS. A genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2014 Jan;46(1):56–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berndt SI, Skibola CF, Joseph V, Camp NJ, Nieters A, Wang Z, Cozen W, Monnereau A, Wang SS, Kelly RS, Lan Q, Teras LR, Chatterjee N, Chung CC, Yeager M, Brooks-Wilson AR, Hartge P, Purdue MP, Birmann BM, Armstrong BK, Cocco P, Zhang Y, Severi G, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Lawrence C, Burdette L, Yuenger J, Hutchinson A, Jacobs KB, Call TG, Shanafelt TD, Novak AJ, Kay NE, Liebow M, Wang AH, Smedby KE, Adami HO, Melbye M, Glimelius B, Chang ET, Glenn M, Curtin K, Cannon-Albright LA, Jones B, Diver WR, Link BK, Weiner GJ, Conde L, Bracci PM, Riby J, Holly EA, Smith MT, Jackson RD, Tinker LF, Benavente Y, Becker N, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Foretova L, Maynadie M, McKay J, Staines A, Rabe KG, Achenbach SJ, Vachon CM, Goldin LR, Strom SS, Lanasa MC, Spector LG, Leis JF, Cunningham JM, Weinberg JB, Morrison VA, Caporaso NE, Norman AD, Linet MS, De Roos AJ, Morton LM, Severson RK, Riboli E, Vineis P, Kaaks R, Trichopoulos D, Masala G, Weiderpass E, Chirlaque MD, Vermeulen RC, Travis RC, Giles GG, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Weinstein S, Clavel J, Zheng T, Holford TR, Offit K, Zelenetz A, Klein RJ, Spinelli JJ, Bertrand KA, Laden F, Giovannucci E, Kraft P, Kricker A, Turner J, Vajdic CM, Ennas MG, Ferri GM, Miligi L, Liang L, Sampson J, Crouch S, Park JH, North KE, Cox A, Snowden JA, Wright J, Carracedo A, Lopez-Otin C, Bea S, Salaverria I, Martin-Garcia D, Campo E, Fraumeni JF, Jr, de Sanjose S, Hjalgrim H, Cerhan JR, Chanock SJ, Rothman N, Slager SL. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013 Aug;45(8):868–876. doi: 10.1038/ng.2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao C, Moult J. GWAS and drug targets. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(Suppl 4):S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-S4-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paulsson K, Lilljebjorn H, Biloglav A, Olsson L, Rissler M, Castor A, Barbany G, Fogelstrand L, Nordgren A, Sjogren H, Fioretos T, Johansson B. The genomic landscape of high hyperdiploid childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2015 Jun;47(6):672–676. doi: 10.1038/ng.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quesada V, Ramsay AJ, Rodriguez D, Puente XS, Campo E, Lopez-Otin C. The genomic landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: clinical implications. BMC Med. 2013;11:124. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mullighan CG. Genome sequencing of lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2013 Dec 5;122(24):3899–3907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-460311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng F, Zhao J, Fooksa M, Zhao Z. A network-based drug repositioning infrastructure for precision cancer medicine through targeting significantly mutated genes in the human cancer genomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016 Mar 28; doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ung M, Liu CC, Cheng C. Integrative analysis of cancer genes in a functional interactome. Scientific Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep29228. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menche J, Sharma A, Kitsak M, Ghiassian SD, Vidal M, Loscalzo J, Barabasi AL. Disease networks Uncovering disease-disease relationships through the incomplete interactome. Science. 2015 Feb 20;347(6224):1257601. doi: 10.1126/science.1257601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossin EJ, Lage K, Raychaudhuri S, Xavier RJ, Tatar D, Benita Y International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics C. Cotsapas C, Daly MJ. Proteins encoded in genomic regions associated with immune-mediated disease physically interact and suggest underlying biology. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(1):e1001273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leiserson MD, Blokh D, Sharan R, Raphael BJ. Simultaneous identification of multiple driver pathways in cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(5):e1003054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, Leiserson MD, Miller CA, Welch JS, Walter MJ, Wendl MC, Ley TJ, Wilson RK, Raphael BJ, Ding L. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013 Oct 17;502(7471):333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomczak K, Czerwinska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19(1A):A68–A77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]