Abstract

Background

The interview visit is an important component of residency and fellowship recruitment that requires a substantial expenditure of time and resources for both training programs and candidates.

Objective

Survey aimed to study the impact of a preinterview dinner on fellowship program candidates.

Methods

A single center preintervention and postintervention comparison study was conducted using an electronic survey distributed to all Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellowship candidates over 3 years (2013–2015). The interview visit in 2013 did not include a preinterview dinner (no-dinner group), while the candidates interviewing in 2014 and 2015 were invited to a preinterview dinner with current fellows on the evening before the interview day (dinner group).

Results

The survey was distributed to all candidates (N = 70) who interviewed between 2013 and 2015 with a 59% (n = 41) completion rate. Ninety percent of respondents (37 of 41) reported that a preinterview dinner is valuable, primarily to gain more information about the program and to meet current fellows. Among candidates who attended the dinner, 88% (23 of 26) reported the dinner improved their impression of the program. The dinner group was more likely to have a positive view of current fellows in the program as desirable peers compared to candidates in the no-dinner group.

Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that a preinterview dinner may offer benefits for candidates and training programs and may enhance candidates' perceptions of the fellowship program relative to other programs they are considering.

Introduction

Recruitment of residency or fellowship candidates is an important part of every graduate medical education training program. Internal medicine programs in the United States spend an estimated $50 million each year on recruitment of residency candidates.1 Recruitment generally involves an in-person interview visit to the host program by each candidate, and across all specialties more than 200 000 interview visits may occur each year nationwide.2 These interview visits require substantial expenditure of time and resources for both training programs and candidates, and they are among the most important evaluative tools for both parties. On a recent National Resident Matching Program survey,3,4 the interview day experience was number 1 of 39 most important factors for program directors and number 2 of 42 most important factors for candidates when ranking candidates and programs, respectively. Despite its importance, the optimal way to structure the interview visit to meet the needs of both candidates and programs has not yet been defined.5–9

Many residency and fellowship programs include a preinterview dinner with current trainees as part of the interview visit. Although the format may vary, the dinner typically occurs on the evening prior to the interview day and is designed to allow candidates to interact with current program trainees in an informal setting. In the United States, 42% of internal medicine residency training programs offer a preinterview dinner.1 However, it is largely unknown whether a preinterview dinner offers any benefits for the program or the candidates. For programs, the interview dinner may enhance candidates' perceptions of the program, thereby improving Match outcomes, but there are financial and resource costs to consider when hosting the dinner. For candidates, the dinner may help them learn more about the program. At the same time, the dinner generally occurs on the day prior to the interview, so it lengthens interview travel days, resulting in increased costs and time away from clinical duties at their home institution. We therefore aimed to study the impact of a preinterview dinner on our fellowship program candidates.

Methods

This was a single center preintervention and postintervention comparison study of all candidates who interviewed for the Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (PCCM) Fellowship at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, over 3 years (2013–2015). The interview visit for 2013 candidates did not include a preinterview dinner (no-dinner group), while the 2014 and 2015 visits included a preinterview dinner (dinner group). The major components of the interview visit were otherwise similar between the 2 groups and included a presentation by the program director, faculty interviews, lunch, and a tour of the facilities.

The format for the preinterview dinner was as follows: an invitation to the preinterview dinner was sent to all candidates accepted for interview. Candidates were then informed that attending the dinner was optional and would not be used for their evaluation. The dinner occurred at a local restaurant on the evening prior to the interview day, and meal costs were provided by the fellowship program. All current fellows were eligible to attend the dinner and self-selected based on availability in an approximate 1:1 ratio with candidates. The dinner did not include any evaluation of the candidates by the fellows. No faculty members attended the dinner.

Each year, an electronic survey was distributed via e-mail to all candidates who interviewed after the fellowship Match results had been finalized. The survey results were collected and stored anonymously. Candidates were asked about the value of a preinterview dinner, and to rank multiple attributes of the Mayo PCCM Fellowship training program as compared to other programs that they visited for interviews on a 5-point Likert scale: “best of all programs visited,” “positive,” “neutral,” “negative,” and “worst of all programs visited.”

The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). P values for comparison between the no-dinner and dinner groups were calculated using Fisher's exact test. Data were analyzed in an intention-to-treat manner, such that all individuals who were invited to the interview dinner were included with the dinner group even if they did not attend the dinner. Survey data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) tools.10

Results

A total of 41 of 70 candidates (59%) completed the survey, including 12 of 23 (52%) from the no-dinner group and 29 of 47 (62%) from the dinner group. A total of 26 of 29 candidates (90%) in the dinner group reported that they attended the dinner, while the remaining 3 did not attend. The direct cost of the dinner to the program was approximately $100 per candidate interviewed, which included meal costs for both candidates and trainees.

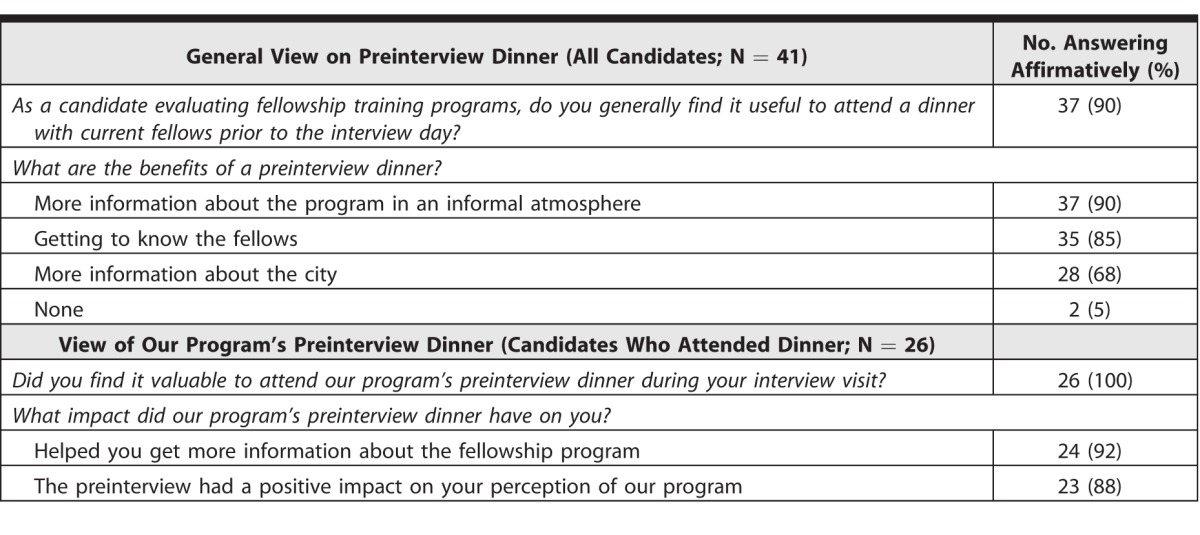

table 1 highlights candidates' attitudes about the preinterview dinner. Nearly all candidates (90%, 37 of 41) stated that it is generally valuable to attend a preinterview dinner. The most commonly cited benefits were acquiring more information about the program in an informal atmosphere and getting to know the current fellows. Of the candidates who attended the dinner, all found it to be beneficial, and most (88%, 23 of 26) reported that it had resulted in a positive impact on their perceptions of the program.

table 1.

Candidate Views on the Benefits of a Preinterview Dinner

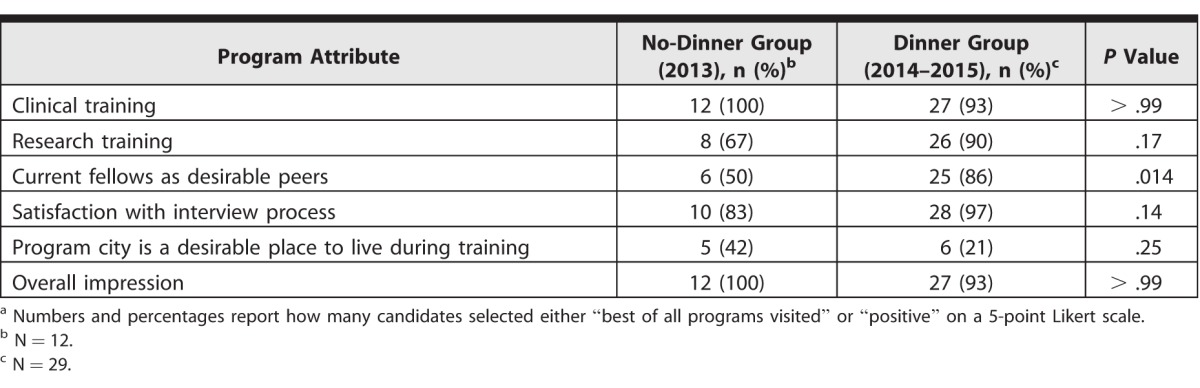

table 2 examines candidates' perceptions of various program attributes in the dinner group compared with the no-dinner group. Candidates in the dinner group had a significantly enhanced perception of current fellows as desirable peers to train alongside (86% favorable) compared with the no-dinner group (50% favorable). There was no improvement in candidates' perceptions of other program attributes.

table 2.

Candidates With Positive View of Our Program's Attributes Compared With Other Programs Visiteda

Discussion

In this pilot study, we found that PCCM Fellowship candidates overwhelmingly reported that a preinterview dinner was valuable, primarily to gain more information about the program and meet current fellows. From the program perspective, the preinterview dinner enhanced candidates' perceptions of the program, specifically in the domain of “current fellows as desirable peers.” This is important, as the interview day in and of itself may offer candidates limited time to interact with current fellows. Therefore, the preinterview dinner may fill an important role by giving candidates sufficient time to meet current trainees and assess their fit in the culture of the training program.

We were aware of only 1 other prior study of preinterview dinner,11 a survey of fourth-year medical students, who similarly reported the preinterview dinner was an important component of the interview visit to learn more about the programs.

Our study has several limitations. We studied a single internal medicine subspecialty program, and our results are not generalizable. We had a small sample size, despite the study spreading over 3 years. Improvements in perception of the dinner group compared with the no-dinner group may have been due to other confounding factors that were not evaluated in our study, such as changes to the interview day presentations or changes in fellow personnel. Our study did not determine whether the interview dinner's primary benefit was simply more time for candidate-fellow interaction or if the off-campus, informal setting was also important. Finally, the study did not examine whether an interview dinner enhances program Match outcomes, but we speculate that a candidate's positive experience at the dinner might improve their ranking of the program. The next research step may be a study of a preinterview dinner in multiple programs across other specialties.

Conclusion

This pilot study suggests that a preinterview dinner is beneficial to PCCM Fellowship candidates.

References

- 1. Brummond A, Sefcik S, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Resident recruitment costs: a national survey of internal medicine program directors. Am J Med. 2013; 126 7: 646– 653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Resident Matching Program. Results and data: 2015 Main Residency Match. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2015_final.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2015 NRMP Applicant Survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Applicant-Survey-Report-2015.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2014 NRMP Program Director Survey. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/PD-Survey-Report-2014.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stephenson-Famy A, Houmard BS, Oberoi S, et al. Use of the interview in resident candidate selection: a review of the literature. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7 4: 539– 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hopson LR, Burkhardt JC, Stansfield RB, et al. The multiple mini-interview for emergency medicine resident selection. J Emerg Med. 2014; 46 4: 537– 543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, et al. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012; 187 4: 1380– 1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brustman LE, Williams FL, Carroll K, et al. The effect of blinded versus nonblinded interviews in the resident selection process. J Grad Med Educ. 2010; 2 3: 349– 353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, et al. Using Skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013; 5 3: 503– 505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42 2: 377– 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schlitzkus LL, Schenarts PJ, Schenarts KD. It was the night before the interview: perceptions of resident applicants about the preinterview reception. J Surg Educ. 2013; 70 6: 750– 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]