The Challenge

A common question posed to qualitative researchers is, “Can I do qualitative research with the free-text entries from our program's evaluations? There's good feedback in there!” While there may be rich, constructive data as free-text entries on end-of-course or end-of-rotation evaluations, using that text as data for research can present problems when it is collected for program evaluation purposes. This Rip Out describes key distinctions between qualitative research and program evaluation, identifies standards for judging quality in program evaluation, and contrasts these standards with standards for judging quality in qualitative research.

What Is Known (or Debated)

Although research and program evaluation are both thorough, systematic inquiries, there is a long-standing debate: Are research and program evaluation theoretically distinct, practically distinct, or one-and-the-same?1 The distinction, if it exists, becomes less clear when available data are qualitative in nature, as when the data are free-text entries on surveys intended for program evaluation. Because educational programs typically consist of dynamic components and unfold in complex, unpredictable contexts, program evaluation may have to adapt over time as program goals are clarified or as interventions give way to new learning.2,3 Thus, inquiry that welcomes complexity, multiplicity, and flexibility seems fitting. In this regard, qualitative research can attend to dynamic social phenomena, such as how educational programs are adapted and become part of routine practice.4 However, there are key differences between research and program evaluation. In this article, we propose that these inquiries are distinct in (1) the issues they address; (2) their intended scope; and (3) the standards they use to judge the quality of the work in general, and the data in particular.

Issues and Scope

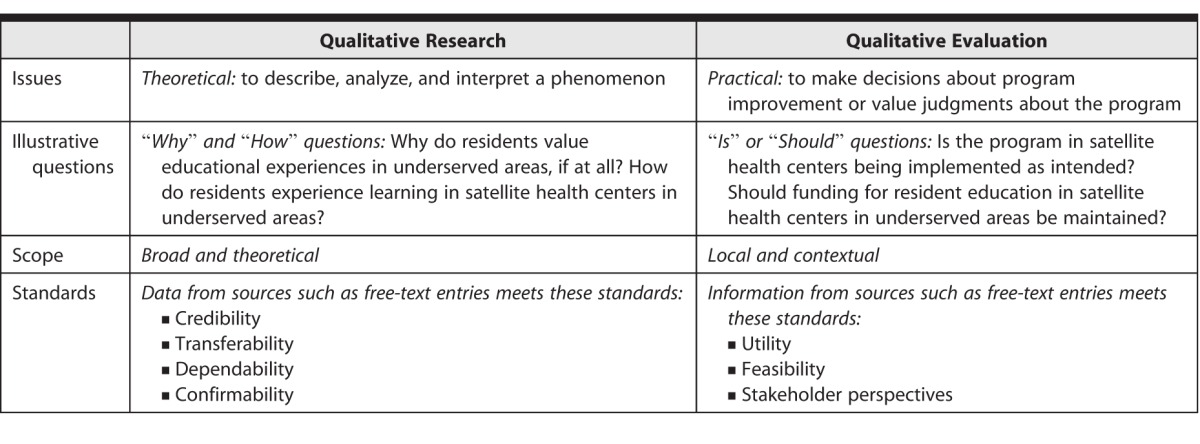

Although qualitative research and program evaluation both seek to understand what is happening, they diverge in issues and scope. Qualitative research usually addresses theoretical issues, asking questions such as, “Why is this happening?” Qualitative researchers then seek to locate the answer to the question in a larger body of literature, and to make claims of relevance to that literature. Conversely, program evaluation usually addresses practical issues and asks questions such as, “What is actually happening” or “What should be happening?” Answers to these questions aim to inform strategies for program improvement or judgments about the worth of a program locally, without stringent claims for transferability to other contexts. Qualitative research may occasionally ask, “What should be happening?” and program evaluation may address, “Why is this happening?” However, the general issues addressed and the project's scope are different (table).

table.

Contrasting Qualitative Research and Program Evaluation

Scenario: As a program director in a tertiary care medical center, you developed a new program for residents to increase their exposure to satellite health centers in underserved areas. You have received constructive written and verbal feedback from your residents after the first year of implementation. You use information in the table below to help you decide whether your next step toward scholarship should be qualitative research or program evaluation.

Standards for Judging Quality

We also propose that research and program evaluation are distinct because they are held to different standards for judging quality, or stated another way, they use different guiding principles. Standards for methodological rigor in qualitative research include the following: Are the data credible (a proxy for internal validity), transferable (a proxy for external validity), dependable (a proxy for reliability), and confirmable (a proxy for objectivity)?5 Standards for program evaluation have a different methodological focus on practical concerns: Are the data useful for informing decisions, feasible to collect, and accurate representations of stakeholder perspectives?6

Why Differences Matter in Scholarship

Medical educators may try, inadvisably, to retrospectively fit responses to free-text questions collected for program evaluation into rigorous standards for qualitative research. This may occur with the desire to disseminate their work in academic journals. For example, rather than describing how information in free-text entries on end-of-rotation evaluations was used to refine an educational program, which would be of interest to evaluators, they focus instead on abundance and credibility of data, of interest to researchers. Similarly, rather than discussing how data collected from interviews with faculty members helped establish the local worth of an online continuing medical education program, which would be of concern to evaluators, they fret about their convenience sampling strategy, of concern to researchers. This is not to say that program evaluation should be conducted less systematically or thoughtfully than research. Rather, the point is that initial decisions about each project will be guided differently: primarily, although not solely, by theoretical issues (research) or by practical issues (program evaluation).

Back to Blurring the Lines

Recently, some medical education scholars have proposed that understanding mechanisms underpinning educational processes, such as how learners learn, is akin to program evaluation.2 From this point of view, methodological rigor of research is required to understand the human processes at play. However, orienting the inquiry toward topics relevant to diverse stakeholder groups leads to program evaluation. By way of illustration, the facilitated feedback model of Sargeant et al,7 designed to build relationship, explore reactions and content, and coach for performance change (R2C2), blends research and program evaluation. The authors undertook a qualitative research study to develop the model, but then intentionally refined the model according to feasibility standards from program evaluation.

How You Can Start TODAY

-

1

Be clear at the start of your project about its purpose when qualitative data are involved (eg, free-text entries). Which standards are indicated: those for qualitative research or those for program evaluation?

-

2

Once the purpose of your project is clear, attend to the appropriate standards.

-

3

Expect qualitative research to meet one set of standards and program evaluation to meet another.

What You Can Do LONG TERM

-

1

Become familiar with models of program evaluation that fit well with qualitative inquiry such as utilization-focused evaluation, developmental evaluation, or realist evaluation.1–3

-

2

When disseminating your program evaluation work, inform your audience of the standards you used to judge the quality of your data, standards which are as important as, but different from, qualitative research.

-

3

Advocate for additional venues in which to disseminate both standard-conforming qualitative research and standard-conforming program evaluation in medical education.

Resources

- 1. Shaw IF. Qualitative Evaluation. London, UK: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haji F, Morin MP, Parker K. Rethinking programme evaluation in health professions education: beyond “did it work?” Med Educ. 2013; 47 4: 342– 351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balmer DF, Schwartz A. Innovations in pediatric education: the role of evaluation. Pediatrics. 2010; 126 1: 1– 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, et al. Choosing a qualitative research approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7 4: 669– 670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. London, UK: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Evaluation Association. The program evaluation standards. http://www.eval.org/p/cm/ld/fid=103. Accessed August 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med. 2015; 90 12: 1698– 1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]