Abstract

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is one of the most frequent sources of distress after treatment for prostate cancer (PCa), yet evidence suggests that men do not easily adjust to loss of sexual function over time. A hypothesized determinant of men's adaptation to ED is the degree to which they experience a loss of masculine identity in the aftermath of PCa treatment.

Aims

The aims of this study were (i) to describe the prevalence of concerns related to diminished masculinity among men treated for localized PCa; (ii) to determine whether diminished masculinity is associated with sexual bother, after controlling for sexual functioning status; and (iii) to determine whether men's marital quality moderates the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother.

Methods

We analyzed cross-sectional data provided by 75 men with localized PCa who were treated at one of two cancer centers. Data for this study were provided at a baseline assessment as part of their enrollment in a pilot trial of a couple-based intervention.

Main Outcome Measures

The sexual bother subscale from the Prostate Health-Related Quality-of-Life Questionnaire and the Masculine Self-Esteem and Marital Affection subscales from Clark et al's PCa-related quality-of-life scale.

Results

Approximately one-third of men felt they had lost a dimension of their masculinity following treatment. Diminished masculinity was the only significant, independent predictor of sexual bother, even after accounting for sexual functioning status. The association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother was strongest for men whose spouses perceived low marital affection.

Conclusions

Diminished masculinity is a prominent, yet understudied concern for PCa survivors. Regardless of functional status, men who perceive a loss of masculinity following treatment may be more likely to be distressed by their ED. Furthermore, its impact on adjustment in survivorship may rely on the quality of their intimate relationships.

Keywords: Masculinity, Prostate Cancer, Prostatectomy, Sexual Function, Sexual Distress, Sexual Dysfunction, Erectile Dysfunction, Sexual Bother, Marital Affection

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-cutaneous cancer diagnosed in American men [1]. Although 5-year survival rates among men treated for early stage disease approach 100% [1], the adverse impact of treatment on quality of life is a prominent concern and often a basis for treatment selection [2,3]. Men contend with a host of treatment-related complications, including declines in sexual, urinary, and bowel functioning [4].

Among the physical side effects that follow treatment, impaired sexual functioning is often ranked the most common long-term complaint [5]. Men frequently experience difficulty achieving an erection, less satisfying and/or non-ejaculatory orgasms, decreased desire and frequency of sexual activity, and poor self-image. In a cohort of 1,288 men with localized PCa post-prostatectomy, 55% had no erection ability 5 years after surgery, and only 28% reported erections firm enough for intercourse [6]. Miller et al. similarly demonstrated a significant decline in sexual function between 2 and 5 years posttreatment among men who received external beam radiation [4].

These disruptions to sexual functioning are often distressing to men [7–10], and broadly undermine their perceptions of physical health and psychosocial well-being [11]. Men with sexual dysfunction posttreatment are more likely to report depressive symptoms [12,13], experience strain and withdrawal in their close relationships, and/or have difficulty communicating about their symptoms [14–16]. The degree to which sexual dysfunction causes men embarrassment and shame, contributes to life dissatisfaction or blocks intimacy is referred to as sexual bother [17,10].

Unfortunately, men who experience sexual bother post-prostatectomy do not easily adjust over time [18]. In a prospective study of 434 men followed up to 5 years post-prostatectomy, only one-third returned to presurgical levels of sexual bother by 12 months after surgery, and a majority sustained high levels of bother at 5 years postsurgery [19]. Nelson et al. found that sexual bother increased significantly at 12 and 24 months post-prostatectomy, compared with a presurgery baseline [10]. When the authors explored contributing factors, none of the variables examined, including age, race, marital status, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value, severity of erectile dysfunction (ED), sexual desire, and intercourse satisfaction, predicted sexual bother postsurgery.

An understudied phenomenon experienced by PCa patients alongside sexual dysfunction is the perceived loss of masculine identity [20]. Masculine identity refers to the sense of coherence in one's identity as derived from valued male norms, which may include self-reliance and potency, competitiveness, control, capacity to be a provider, and restraint from showing dependence or vulnerability [8,21– 23]. Outside of qualitative studies that have documented men's experiences following treatment for PCa [24], there has been little focused investigation of changes in masculine identity following treatment and its contribution to distress. The quality of marital affection and intimacy in men's relationships has been postulated to impact significantly on masculine identity such that open communication, affection, and support from a partner may counter any sense of attack on male identity [16,22,25,26]. This would be consistent with recent evidence that relationship intimacy may play a critical role in facilitating psychosocial adaptation among men with localized PCa [26]. Identifying factors that contribute to the maintenance of sexual bother is an important step toward determining which men are most at risk for poor adaptation in following treatment. Given that a significant portion of men do not appear to adapt satisfactorily to the loss of sexual function, such data can inform efforts to optimize postoperative recovery.

In this study, we examined the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother in a cross-sectional sample of men treated for localized PCa. We used a validated, PCa-specific questionnaire to capture a range of masculinity-related concerns. We further examined whether the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother was moderated by the quality of affection in men's marital relationships. Research examining men's distress following treatment for PCa has given considerable attention to the perspective of the marital partner, who is seen as playing a key role in facilitating the patients' adaptation [16,27-29]. We included in our analysis the partners' perception of marital quality in addition to that of the patient because there is evidence that in couples coping with PCa, the partner's behavior in the relationship (e.g., degree to which she holds back affection or communication) is highly predictive of patient distress [26].

Our study aims are as follows: (i) to describe the prevalence of concerns related to diminished masculinity among men treated for localized PCa; (ii) to determine whether diminished masculinity is associated with sexual bother, after controlling for sexual function status (e.g., erectile functioning, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction); and (iii) to determine whether marital affection, as perceived by men and/or their spouses, moderates the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother.

Methods

Sample

Participants were 75 men treated for localized PCa and their partners. Patients and their partners were recruited from one of two cancer centers: Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC; N = 60 couples) and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC; N= 15 couples). Data were provided during a baseline assessment that was completed as part of enrollment in a larger pilot trial testing the efficacy of a couple-based intervention for men with early stage PCa and their partners [30]. In order to be eligible for this larger trial, and therefore for the current study, men in all couples were required to have a past year diagnosis of localized PCa treated with surgery or radiation, be married or living with their partner of either gender, have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 [31], and geographic proximity to the recruitment site. Eligible men and their partners had to be 18 or older, English speaking, and without hearing impairment. Couples enrolled in the larger trial were randomized to receive either standard care (no intervention), or an Intimacy-Enhancing Couples Therapy, designed to improve communication about cancer-related concerns with a particular focus on the impact of cancer on intimacy. Data presented in this article were collected from men and their partners prior to randomization to treatment arm. Over half of men (N = 42, 56%) were not receiving any penile rehabilitation. Of those receiving ED treatment (N = 33), the majority (N = 31) were receiving medication, with the remaining two men using a pump or injection. Of the 340 couples initially approached for this trial, 75 (21 %) provided consent and returned questionnaires. The most common reasons for study refusal were: the study would “take too much time” (15.6%), no perceived benefit (10.7%), one partner was unwilling (7.7%), geographical distance (7.7%), disliked couples format of intervention (0.4%), already participating in other research studies (1.1%), and “Other” (56%), which included health-related and logistical barriers, or couples who initially agreed to participate but were then unresponsive to follow-up. Comparisons between participating couples and study refusers on demographic and disease-related variables indicated that among refusers, the patient was older (mean age = 64.19 years vs. 60.64 years, t = 3.258, P < 0.01) and had been diagnosed more recently than those enrolled (mean months since diagnosis = 0.6 vs. 7.05, t = -10.187, P < 0.001). An examination of site differences on demographic and study variables (age, race, duration of relationship, household income, cancer stage, type of treatment) indicated that MSKCC patients had significantly higher mean household incomes (F[1, 55] = 15.21, P < 0.001), significantly shorter duration of marriage (F[1, 71] = 5.029, P < 0.05), and were more likely to have had surgery (χ2 [2] = 9.88, P < 0.01) than patients recruited from FCCC. Site was therefore controlled in subsequent analyses.

Procedure

Eligible men and their partners were contacted by telephone, letter, or were approached after an outpatient visit by a research study assistant. Those interested were asked to provide informed consent and return a completed questionnaire battery by mail. Participants signed an informed consent that was approved by the institutional review boards of each site. Participants were contacted weekly by telephone until questionnaires and consent forms were returned.

Main Outcome Measures

International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) [32] is a 15-item questionnaire administered to patients only, and used to assess sexual functioning over the last month. We examined the following three domains: level and frequency of sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and erectile functioning. Responses were on five- and six-point Likert scales. The IIEF demonstrated a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha values above 0.90).

Sexual Bother was assessed using the three-item sexual bother subscale of the Prostate Health-Related Quality-of-Life questionnaire [17], administered to patients only. Men rate the degree to which, in the last 4 weeks, concerns about sexual functioning were a problem for them, led them to feel embarrassed or ashamed, or interfered with enjoyment of their life. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.82).

Diminished Masculine Identity was assessed for patients only using the eight-item “masculine self-esteem” subscale from Clark et al.'s PCa-related quality-of-life subscales [20]. Men rated the degree to which they feel a loss of masculinity on a five-point Likert scale (e.g., “I feel as if I am no longer a whole man”). For the current analyses, items were reverse-scored, such that higher scores reflect better “masculine self-esteem” or less disruption to masculinity (Cronbach's alpha = 0.89).

Marital Affection was assessed for men and their partners using the six-item “marital affection” subscale from Clark et al.'s PCa-related quality-of-life subscales [20] (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86). Responses were on a five-point Likert scale, and items were reverse-scored, with higher scores reflecting sustained intimacy and affection.

Results

Description of Sample

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients and their partners in this study were Caucasian, had at least college-level education, and a mean age of 60.6 (standard deviation [SD] = 8.2) and 53.3 years (SD = 15.8), respectively. All were married or cohabitating with their significant other for a mean of approximately 27 years (SD = 15). Most men (N = 44, 58.9%) had undergone surgery (26.7% radical prostatectomy, 30.7% laparoscopic surgery) and 32% (N = 24) had radiation treatment.

Table 1. Description of Sample (N = 75 patients, partners).

| Patients | Partners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| N (%)* | M(SD) | N (%)* | M(SD) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 75 (100) | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Female | 0 (0) | 73 (97.3) | ||

| Age | 60.6 (8.2) | 53.3 (15.8) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 66 (88) | 60 (83.3) | ||

| Non-White | 9 (12) | 8 (11.1) | ||

| Education | ||||

| Partial or complete high school | 9 (12) | 16 (21.3) | ||

| Partial or complete college | 29 (38.6) | 23 (30.6) | ||

| Partial or complete graduate school | 37 (49.3) | 32 (42.6) | ||

| Duration of relationship (years) | 27.6 (15.1) | 27.5 (15.2) | ||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 8.1 (5.4) | |||

| Treatment | ||||

| Surgery | 43 (57) | |||

| Radiation and/or hormone therapy | 24 (32) | |||

| Received ED treatment | 33 (44) | |||

Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Table 2 presents the mean (M) and SD of all study variables, as well as intercorrelations between study variables. The mean sample score on the erectile functioning domain subscale (M = 14.35, SD = 11.08) was within the range of scores observed among non-cancer patients with moderate ED [32], and sits well below the established cutoff for functional erections (25) [33]. The mean score was also similar to that published for a population of PCa patients 12 months postsurgery (M = 14.5, SD = 10.0) [10]. The majority of men in this sample (N = 49, 65.3%) scored below the established cutoff score of 25, classifying them as having poor erectile functioning. Mean scores on sexual desire and intercourse satisfaction subscales (M = 6.07, SD = 2.4, and M = 5.56, SD = 5.51, respectively) were comparable with the scores observed in a sample of men with ED (M = 6.4, SD = 1.9, and M = 5.5, SD = 3.0, respectively [32]). The mean sexual bother score (M = 5.22, SD = 2.67) was comparable with that reported by Nelson et al. for a sample of PCa patients at 12 and 24 months post-prostatectomy [10].

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Loss of masculine identity‡ | — | 0.61* | 0.31* | −0.68* | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 85.34 | 16.13 |

| 2. Marital affection—patient | 0.61* | — | 0.50* | −0.68* | 0.27† | 0.06 | 0.21 | 94.42 | 10.37 |

| 3. Marital affection—spouse | 0.31* | 0.50* | — | −0.38* | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 93.19 | 9.97 |

| 4. Sexual bother | −0.68* | −0.68* | −0.38† | — | −0.38* | −0.22 | −0.27 | 5.22 | 2.67 |

| 5. IIEF—erectile functioning | 0.37* | 0.28† | 0.06 | −0.38* | — | 0.60* | 0.91* | 14.35 | 11.80 |

| 6. IIEF—sexual desire | 0.26 | 0.06 | −0.07 | −0.22 | 0.60* | — | 0.57* | 6.07 | 2.40 |

| 7. IIEF—intercourse satisfaction | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.05 | −0.27† | 0.91* | 0.57* | — | 5.56 | 5.51 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

This scale was reverse-scored such that higher values indicate greater masculine self-esteem.

In order to identify variables to be controlled in subsequent analyses, Pearson product correlations were computed to determine whether the primary outcome, sexual bother, was related to ethnicity, pretreatment PSA, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score, and analysis of variance was used to test differences in mean symptom bother across categories of ethnicity, treatment type, and ECOG. None of these variables were significantly associated with sexual bother, and so we did not include these in our main analyses. Because age is commonly associated with sexual functioning, and in this sample was significantly correlated with sexual desire scores on the IIEF (r = −0.35, P < 0.05), we controlled for age in subsequent analyses.

Aim 1: To Determine the Prevalence of Concerns Related to Loss of Masculinity Among Men Treated for Localized PCa

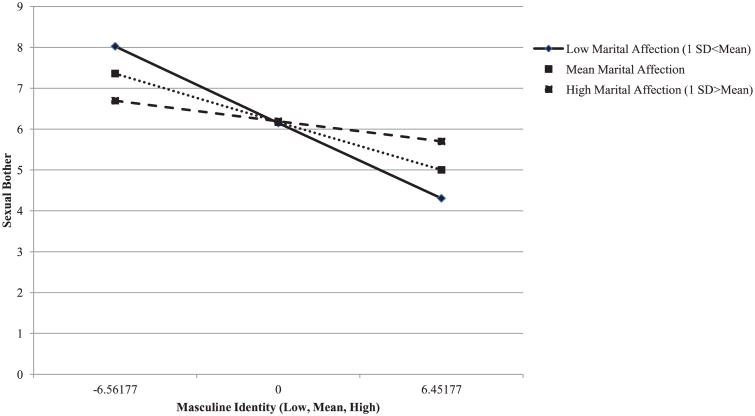

We calculated and plotted the proportion of men who endorsed statements with moderate to high agreement on the diminished masculinity sub-scale (see Figure 1). Statements most commonly endorsed by men were those describing global loss of masculinity (e.g., “feeling I am not the man I used to be,” “feeling I have lost part of my manhood”). Approximately one-third of men (30–37%) rated loss of masculinity as moderate to severe.

Figure 1.

Percentage of men who endorsed moderate to high agreement with dimensions of masculine identity.

Aim 2: To Determine Whether Loss of Masculinity Is Associated with Sexual Bother After Controlling for Sexual Functioning Status

We conducted a multivariate analysis predicting sexual bother, simultaneously entering site as a dummy variable, patient age, scores on the loss of masculine identity subscale, and three IIEF sub-scale scores related to men's reported sexual functioning (i.e., erectile functioning, levels of sexual desire, and intercourse satisfaction). Predictors were centered prior to entry. The model was significant (F = 9.65, P < 0.001) and explained 48% of the variance in sexual bother scores. Loss of masculinity was the only significant predictor in the equation (standardized β = −0.63, t = −6.1, P < 0.001).

Aim 3: To Determine Whether Marital Affection, as Perceived by Men and/or Their Spouses, Moderates the Association Between Loss of Masculinity and Sexual Bother

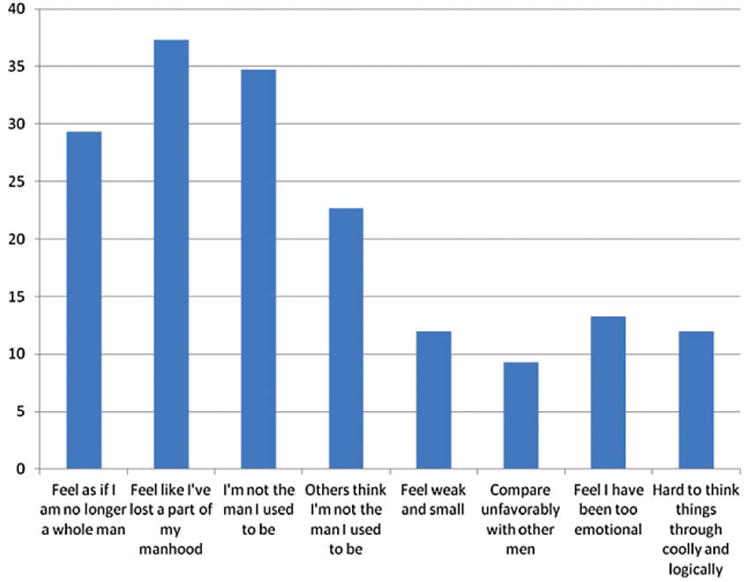

Regression analyses were conducted with patient and partner-reported marital affection added separately in a second step. In a third step, interaction terms representing masculinity by marital affection were entered into the model (see Table 3). Marital affection, as rated by partners, was a significant moderator of the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother (standardized (β = 0.30, t = 2.30, P < 0.05). Interpretation of the significant interaction between marital affection and diminished masculinity is illustrated in Figure 2, where centered predicted values for mascuhnity against sexual bother were plotted for participants 1 standard deviation below, at, and above the mean on marital affection. As shown, loss of masculine identity was more strongly related to sexual bother for those men whose spouses perceived low marital affection. A simple slope analysis [34] indicated that the regression slope of sexual bother on masculine identity was significantly negative at low marital affection (t =−5.37, P < 0.001).

Table 3. Regression of sexual bother on masculine identity and marital affection.

| Variable(s) | R2 | β† | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 0.48 | |||

| Site (MSKCC) | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.96 | |

| Patient age | −0.02 | −0.17 | 0.87 | |

| IIEF—Erectile functioning | −0.10 | −0.42 | 0.68 | |

| IIEF—Sexual desire | 0.04 | 0.35 | 0.73 | |

| IIEF—Intercourse satisfaction | −0.07 | −0.30 | 0.77 | |

| Masculine identity | −0.63 | −6.1 | <0.001 | |

| Step 2 | 0.59 | |||

| Marital affection, patient report | −0.39 | −3.28 | 0.002 | |

| Marital affection, partner report | −0.06 | −0.59 | 0.56 | |

| Step 3 | 0.63 | |||

| Masculine identity × Marital affection, patient report | −0.14 | −0.74 | ||

| Masculine identity × Marital affection, partner report | 0.30 | 2.31 | 0.02 |

Note: All predictor variables were centered prior to entry Into the model.

Standardized regression coefficients are reported.

Figure 2.

Interaction between masculine identity and partner's perception of marital affection in predicting sexual bother.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of masculinity concerns in a sample of 75 men treated for localized PCa, and to examine whether the perceived loss of masculinity posttreatment is associated with sexual bother, a measure of ED-related distress. Approximately one-third of men in this sample endorsed moderate to significant loss of masculinity, and as predicted, diminished masculinity was the largest contributor to sexual bother post-prostatectomy, over and above indices of sexual functioning (e.g., severity of ED, reduced sexual desire, and intercourse satisfaction). Furthermore, the quality of affection in men's intimate relationships, especially as viewed by the partner, was a significant moderator of the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother.

Although loss of sexual functioning is a frequent long-term complaint after treatment for PCa and is often associated with significant distress, we know little about what determines men's adjustment to these symptoms. Bokhour et al. [8,35] argued that when men are distressed by ED, it may have less to do with their sexual performance per se, and more to do with the resulting changes in self worth and quality of their intimate relationships. Prior research similarly suggests that the extent to which men are bothered by loss of sexual function may be weakly related to their sexual functioning status [10,19]. As noted by Clark et al. [20], quality of life appraisals that focus on functional outcomes can obfuscate the more subjective sequelae of treatment. Indeed, a substantial body of work has elaborated on the psychosocial changes experienced by women with breast cancer, particularly in domains of body image and sexual identity. Wall and Kristjanson [36] have argued that the limited scope of our inquiry into identity-related changes after a diagnosis of PCa is itself attributable to assumptions among investigators about men's adherence to masculine ideals in their response to illness.

Diminished masculinity was the largest predictor of sexual bother, yet we cannot rule out that this association is bidirectional. That is, it is conceivable that elevated sexual bother may increase men's sense of vulnerability and embarrassment, thus further challenging their masculine identity. Although the focus here was on the association between masculinity and sexual bother, it is possible that masculine identity is challenged by broader aspects of illness as well (e.g., increased dependency, vulnerability), and therefore may be affected at diagnosis, prior to the onset of ED.

The association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother was strongest for men whose spouses perceived low marital affection. This underscores the importance of men's relational context in their postoperative recovery. A close and communicative relationship can buffer distress and facilitate optimal adaptation in the face of illness [37]. Our findings suggest that men's capacity to sustain intimacy may be an important factor contributing to their adjustment to ED. It is noteworthy that it was the spouse's perception of marital affection that proved to be a significant moderator of the association between diminished masculinity and sexual bother. Items on the marital affection subscale focused on mutual distancing and avoidance (e.g., “I avoid embracing or caressing my partner”). A recent study reported that withdrawal behavior in close relationships was associated with greater distress for men with PCa [26]. There is also evidence that men with PCa are at greater risk for poor adjustment when they experience social constraints in their close relationships, defined as avoidance of, or discomfort with, talking about cancer [38]. Men with ED commonly experience apprehension about sexual contact, but when the partner joins the patient in avoiding sexual intimacy, the cycle of mutual withdrawal that ensues may inadvertently reinforce men's sense of having lost a vital and valued part of their identity. Without open communication and support, couples are hard-pressed to find alternative constructions of masculinity that do not hinge on sexual performance.

Some preliminary data has shown benefit of a couple-based approach to helping men with localized PCa and their partners adapt to treatment-related symptoms and develop or sustain open communication and intimacy [30]. Our data suggest that such interventions should address the masculinity-related changes that men experience but may have difficulty verbalizing. Helping partners to understand and respond with empathy and reassurance to men's concerns about their loss of masculinity may help reduce ED distress. Our data suggest that identifying the subset of men who experience a loss of masculinity will be important in determining who is at risk for adjustment difficulties and therefore warrants such an intervention.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, there was a relatively high study refusal rate. Enrollment rates in studies evaluating couple-focused interventions are typically lower than observational studies due to the necessity of attending conjoint therapy sessions. The relatively high rate of refusal limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies are needed to evaluate factors that increase acceptance rates (e.g., monetary reimbursement). Second, participants were all married or cohabitating with a long-term partner, by virtue of the inclusion criteria established for the larger intervention trial in which they were participating. Our findings may not generalize to unpartnered men, for whom loss of sexual functioning may have different implications (e.g., dating, disclosure to new partners). Third, our sample was comprised almost entirely of heterosexual couples, which does not allow conclusions to be drawn about same-gender relationships. Fourth, the measure used to assess diminished masculinity provided limited information about what meanings underlie global descriptions of “manhood” or “being a whole man,” although these items were derived directly from statements made by men with PCa during focus group discussions [39]. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study, and lack of a control group, prevented inferences about causal relationships between masculine identity, sexual bother, and marital affection. We were unable, for instance, to distinguish men with longstanding marital difficulties from men whose marital functioning was compromised by their cancer and treatment-related side effects.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to quantify the association between men's perceptions of disrupted masculinity and their adjustment to loss of sexual functioning following treatment for localized PCa. Improved understanding of how men respond to the identity-related changes brought by illness will provide important clues about how to best facilitate their recovery.

Conclusion

Regardless of functional status, men who feel they have lost their masculine identity following treatment for localized PCa are likely to be distressed by their ED. This distress includes shame, embarrassment, and a global reduction in quality of life. Diminished masculinity is a prominent, yet understudied concern for PCa survivors. Furthermore, its impact on their adjustment to ED in survivorship may rely to some extent on the quality of marital affection in their intimate relationships.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a P30 CA006927 grant to Fox Chase Cancer Center and by a Memorial Sloan-Kettering Society grant to David Kissane. We thank Sara Worhach, Kristen Sorice, and Megan Eisenberg for data collection, and we thank referring clinicians, and participating couples.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

-

Conception and DesignSharon Manne; David Kissane; Talia Zaider; Christian Nelson

-

Acquisition of DataTalia Zaider; Sharon Manne; David Kissane; John Mulhall; Christian Nelson

-

Analysis and Interpretation of DataTalia Zaider; Sharon Manne; David Kissane; Christian Nelson; John Mulhall

-

Drafting the ArticleTalia Zaider

-

Revising It for Intellectual ContentSharon Manne; David Kissane; John Mulhall; Christian Nelson; Talia Zaider

-

Final Approval of the Completed ArticleTalia Zaider; Sharon Manne; Christian Nelson; John Mulhall; David Kissane

References

- 1.ACS Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Love AW, Scealy M, Bloch S, Duchesne G, Couper J, Macvean M, Costello A, Kissane DW. Psychosocial adjustment in newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:423–9. doi: 10.1080/00048670801961081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gacci M, Simonato A, Masieri L, et al. Urinary and sexual outcomes in long-term (5+ years) prostate cancer disease free survivors after radical prostatectomy. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2009;7:94–102. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Pimentel H, Sandler HM, McLaughlin WP, Wei JT. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: Health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2772–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104:2565–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, Li L, Albertsen PC, Gilliland FD, Hamilton A, Hoffman RM, Stephenson RA, Potosky AL, Stanford JL. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Fredrikson M, Arver S, Steineck G. Waning sexual function—The most important disease-specific distress for patients with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1417–21. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: Exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:649–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray RE, Fitch M, Davis C, Phillips C. Interviews with men with prostate cancer about their self-help group experience. J Palliat Care. 1997;13:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson CJ, Deveci S, Stasi J, Scardino PT, Mulhall JP. Sexual bother following radical prostatectomyjsm. J Sex Med. 2010;7:129–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacon CG, Giovannucci E, Testa M, Glass TA, Kawachi I. The association of treatment-related symptoms with quality-of-life outcomes for localized prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;94:862–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:560–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts KJ, Lepore SJ, Hanlon AL, Helgeson V. Genitourinary functioning and depressive symptoms over time in younger versus older men treated for prostate cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:275–83. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badr H, Taylor CLC. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:735–16. doi: 10.1002/pon.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boehmer U, Clark JA. Communication about prostate cancer between men and their wives. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couper J, Bloch S, Kissane D, Love A, Macvean M. Psychosocial adjustment of partners of patients facing prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:S86–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Befort CA, Zelefsky MJ, Scardino PT, Borrayo E, Giesler RB, Kattan MW. A measure of health-related quality of life among patients with localized prostate cancer: Results from ongoing scale development. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2005;4:100–8. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2005.n.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M, Banez LL, Schroeck FR, Gerber L, Qi J, Satoh T, Baba S, Robertson CN, Walther PJ, Donatucci CF, Moul JW, Polascik TJ. Factors predicting early and late phase decline of sexual health-related quality of life following radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2935–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker WR, Wang R, He C, Wood DP., Jr Five year expanded prostate cancer index composite-based quality of life outcomes after prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011;107:585–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Measuring patients' perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med Care. 2003;41:923–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broom A. Prostate cancer and masculinity in Australian society: A case of stolen identity? Int J Mens Health. 2004;3:73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chappie A, Ziebland S. Prostate cancer: Embodied experience and perceptions of masculinity. Sociol Health Illn. 2002;24:820–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men's health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliffe J. Constructions of masculinity following prostatectomy-induced impotence. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connell RW. Masculinities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manne S, Badr H, Zaider T, Nelson C, Kissane D. Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:74–85. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cliff AM, MacDonagh RP. Psychosocial morbidity in prostate cancer: II. A comparison of patients and partners. BJU Int. 2000;86:834–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornblith AB, Herr HW, Ofman US, Scher HI, Holland JC. Quality-of-life of patients with prostate-cancer and their spouses—Value of a data-base in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez MA, Skinner EC, Meyerowitz BE. Sexuality and intimacy following radical prostatectomy: Patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychol. 2002;21:288–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: A pilot study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zubrod CG, Schneiderman M, Frei E, Brindley C, Gold G, Schnider B. Appriasal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: Comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. J Chronic Disord. 1960;11:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Quirk F, Maytom MC, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Some developments on the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Drug Inf J. 1999;33:179–90. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31:437–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bokhour BG, Powel LL, Clark JA. No less a man: Reconstructing identity after prostate cancer. Commun Med. 2007;4:99–109. doi: 10.1515/CAM.2007.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wall D, Kristjanson L. Men, culture and hegemonic masculinity: Understanding the experience of prostate cancer. Nurs Inq. 2005;12:87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banthia R, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, Ko CM, Sadler GR, Greenbergs HL. The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26:31–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1021743005541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and mental health after prostate cancer. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Bokhour BG, Krasnow SH, Robinson RA, Spaulding M, Talcott JA. Patients' perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3777–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]