Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Even with the advent of evidence-based interventions, an ongoing concern in clinical practice is how to help dementia caregivers determine what type of support is best for them absent a laborious process of trial and error. To help address this practice gap, the present study developed and tested the feasibility of “Care to Plan” (CtP), an online resource for dementia caregivers (e.g., relatives or unpaid nonrelatives) that generates tailored support recommendations.

Design and Methods:

Care to Plan was developed using an iterative prototype and testing process with the assistance of a 29-member Community Advisory Board. A parallel-convergent mixed methods design (quan + QUAL) was used that included a post-CtP survey and a brief semistructured interview to capture in-depth information on the utility and feasibility of CtP. The sample included 30 caregivers of persons with dementia.

Results:

The integrated qualitative and quantitative data indicated that CtP was simple and easy to understand, the streamlined visual layout facilitated utility, and the individualized recommendations could meet the needs of users. Key barriers to use included the need for additional features (e.g., video introductions of caregiver support types) to further guide dementia caregivers’ potential use of tailored support.

Implications:

The multiple data sources underscore the high feasibility and utility of CtP. By describing, identifying, and prioritizing support, CtP could help to improve the care planning process for dementia caregivers. Future dissemination efforts should aim to demonstrate how CtP can be implemented seamlessly within current family caregiver support systems.

Key Words: Alzheimer’s disease, Family caregiving, Online, Intervention, Personalized, Tailored support

If I am a family member/nonrelative caregiver who provides help to someone with memory loss, where do I start to find the support strategy that is right for me? This is a question that likely occurs among distressed caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia (ADRD). There are an ever-growing number of service options for dementia caregivers to choose from, ranging from support groups to psychotherapy. An ongoing concern, however, is how to help dementia caregivers determine whether a certain type of support is best for them absent a laborious process of trial and error (i.e., tailored support). Individual professionals may serve as a source of tailored support but barriers/limitations ranging from availability, to restricted experience, to professional biases may influence their suggestions (Kane, Bershadsky, & Bershadsky, 2006; Kane, Boston, & Chilvers, 2007). Although quality evidence has emerged to support dementia caregiver interventions and their implementation across a range of community and clinical contexts (Gitlin & Hodgson, 2015; Gitlin, Marx, Stanley, & Hodgson, 2015), there remains a gap as to whether or how these various evidence-based protocols are potentially tailored to the often heterogeneous needs of individual dementia caregivers (Van Mierlo, Meiland, Van der Roest, & Droes, 2012).

An unmet need indicated by many dementia caregivers is a lack of quality information about support strategies or services that can help ease the challenges of their care situations (Gaugler & Kane, 2015). “Quality information” in this context represents information, guidance, or consultation that is effectively tailored to meet the needs of individual dementia caregivers in ways that are helpful and feasible. Evidence-based, comprehensive psychosocial interventions are in various stages of translation across multiple regions in the United States (Burgio et al., 2009; Gitlin et al., 2015; Mittelman & Bartels, 2014; Nichols, Martindale-Adams, Burns, Zuber, & Graney, 2014), but such services are often presented as “one-size fits all” solutions. Whether all dementia caregivers are likely to benefit from or prefer comprehensive support protocols is poorly understood. Even with the advent of detailed online resources such as Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral (ADEAR; https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers) or the Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org), there is a lack of tailored support that can directly meet the diverse needs of caregivers or persons with dementia (Anderson, Nikzad-Terhune, & Gaugler, 2009).

The objective of the current project was to develop and test “Care to Plan” (CtP), an online recommendation tool for dementia caregivers who provide help to persons with ADRD. CtP is organized to include the following two steps: (1) generation of tailored support recommendations (Kane et al., 2006, 2007) and (2) provision of guidance to facilitate the caregiver’s selection of a recommended support option. In offering this guidance, CtP aims to advance the state-of-the-art in science and current clinical practice by complementing ongoing efforts to improve case management practice (Montgomery, Kwak, Kosloski, & O’Connell Valuch, 2011) and efficiently link dementia caregivers to tailored support recommendations. The questions guiding this project were as follows: (1) How do caregivers perceive the clarity and ease of use of CtP? and (2) How and why do users perceive CtP can help enhance their caregiving situations?

Conceptualization of Care to Plan

The evaluation of CtP was guided by conceptual models of decision making and dementia caregiving. Specifically, the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF; see https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html) is designed to inform the development of decision-making aids to help patients make better clinical decisions and provide clinicians with the tools to facilitate such decisions. The ODSF, drawing on multiple health behavior theories and models, is premised on the belief that decisional needs influence decision quality and health service use, but decisional support via counseling or tools (e.g., decision-making aids) can improve the quality of a given decision. These principles were embedded in the design, structure, and content of CtP (see the following paragraphs). The ODSF has been widely used in improving medical decisions across various disease contexts, especially in instances where there is no clear best treatment. A measure of decision-making quality (decisional acceptability) was also used to determine the feasibility and utility of CtP in the current study, as it was anticipated that CtP has the potential to enhance dementia caregivers’ perceptions of making decisions regarding their own support. In addition, conceptual models of dementia caregiving highlight a number of long-term, key outcomes that an online recommendation tool such as CtP may influence. Specifically, the Stress Process Model has been used extensively to study the manifestation of negative outcomes in dementia caregiving (e.g., caregiver stress, caregiver depression, care recipient nursing home admission; see Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995; Hilgeman et al., 2009; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990). The Stress Process Model is based on the mechanism of “proliferation,” where the emotional stress of care provision to a person with dementia (primary stress) spreads to other life domains which are then posited to negatively influence various caregiving outcomes. A care planning tool such as CtP would be viewed within the stress process model as a resource that could stem the proliferation of stress to more global caregiver and care recipient outcomes. As the manifestation of stress process model outcomes often requires longer-term evaluation, they will serve as a principal focus of subsequent studies of CtP efficacy.

Overview

The first step in developing CtP was to build the online tool so that any combination of answers a dementia caregiver provided on a needs assessment would generate a tailored support recommendation. Following this initial developmental step and the creation of the online CtP portal, the feasibility and utility of the CtP prototype version was tested with 21 dementia caregivers. A parallel-convergent mixed methods design was used to test the feasibility and utility of the CtP prototype (quan + QUAL), with integration of the qualitative and quantitative components occurring via the joint presentation of both types of data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2010). Throughout and immediately following prototype feasibility and utility testing, the project’s 29-member Community Advisory Board reviewed the initial version of the CtP during quarterly meetings (n = 4) and offered additional insights and feedback as to the content, structure, and appearance of the tool. These changes were incorporated into a beta version, which was again tested using a parallel-convergent mixed methods design with an additional nine dementia caregivers. Institutional review board approvals were granted for the various phases involved in building and testing CtP (for the current study, expedited approval was granted).

Development and Design of Care to Plan

Ideally, the identification of tailored support for dementia caregivers in different situations would be based on scientific evidence, but such information is not readily available (Gaugler, Potter, & Pruinelli, 2014; Gitlin & Hodgson, 2015; Van Mierlo et al., 2012). For these reasons, CtP relied on a robust base of clinical expert recommendations when constructing tailored support recommendations. Details on how clinical expert recommendations were secured are reported elsewhere (Gaugler, Westra, & Kane, 2015). A total of 422 clinical professionals and scientific experts from throughout the United States viewed a series of hypothetical dementia caregiver scenarios. These experts completed a total 6,890 scenario ratings. In each scenario, six dimensions representing those measured by the brief, validated Risk Appraisal Measure (RAM) were varied systematically as shown in the left hand column of Table 1 (Czaja et al., 2009). The six dimensions of RAM were combined with a single variation of each characteristic in the right hand column of Table 1 sequentially. These additional characteristics were based on their empirical associations with dementia caregiver distress and persons’ with ADRD risk for nursing home admission (Gaugler, Yu, Krichbaum, & Wyman, 2009; Gaugler et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Dementia Caregiver Scenarios

| Randomly varieda | Single characteristics varied separatelyb |

|---|---|

| Caregiver depressive symptoms (caregiver is depressed: yes/no) | Care recipient lives with caregiver (yes/no) |

| Caregiver burden (caregiver is burdened: yes/no) | Care recipient is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (yes/ other dementia diagnosis) |

| Caregiver self-care (caregiver is at low-risk for self-care/healthy behaviors: yes/no) | Care recipient dementia severity/stage (early, middle, late) |

| Caregiver social support (caregiver has social support: yes/no) | Caregiver kin relationship to care recipient (wife, daughter, husband, other relationship) |

| Care recipient behavior problems (care recipient is at-risk for behavior problems: yes/no) | |

| Care recipient safety problems: (care recipient is at-risk for safety problems related to her/ his dementia: yes/no) |

Notes: aFor each set of scenarios, a random combination of possible answers for all six of the characteristics in this column were presented.

bFor each characteristic in this column, raters were presented with a single value of each characteristic (e.g., care recipient lives with caregiver) one at a time and asked to recommend a dementia caregiver intervention that they deemed most appropriate for that particular scenario.

Experts were then asked to assign a score of 1–7 (with one the highest recommendation) across seven caregiver intervention types that could best assist/help the dementia caregiver in that particular scenario. The seven intervention types were broadly aligned with attempts to categorize dementia caregiver interventions in various reviews and meta-analyses (Gitlin & Hodgson, 2015; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006) and included psychoeducation, case management/counseling, support groups, respite, training of the person with dementia (cognitive rehabilitation), psychotherapy, and multicomponent approaches (e.g., combinations of multiple service modalities, such as individual and family counseling and support groups). Relying on the results of the expert recommendations and extrapolating predicted recommendations using general linear models, we were able to match any combination of answers on the CtP needs assessment (the 20 items measuring the domains in Table 1). Specifically, expert ratings were analyzed to estimate the empirical associations between each combination of answers on the CtP needs assessment and the tailored support recommendations. Weighted averages were then used to create recommendation ratings for every possible combination of responses on the CtP needs assessment (Kane et al., 2007).

The CtP web-based portal was then constructed. The Mill City Collaborative Innovation Center provided technical assistance to the team to build the CtP web portal. Care to Plan was developed using an iterative development process to ensure that components of the system and the system as a whole met CtP’s objectives. The development process had a feedback loop so project staff could review project and page components while in development and initiate necessary changes. Additional usability testing was completed by J. E. Gaugler and M. Reese as well as Mill City Collaborative Innovation Center staff to ensure the application interface was easy to read, understand, and use. Care to Plan then underwent automated unit testing to ensure all system components worked individually. The application was also run through a standard system testing methodology to ensure the application was fully functional. The testing process verified correct assessment content, report scoring, expected web page functionality, exception handling, database interaction and persistence, and cross-browser support.

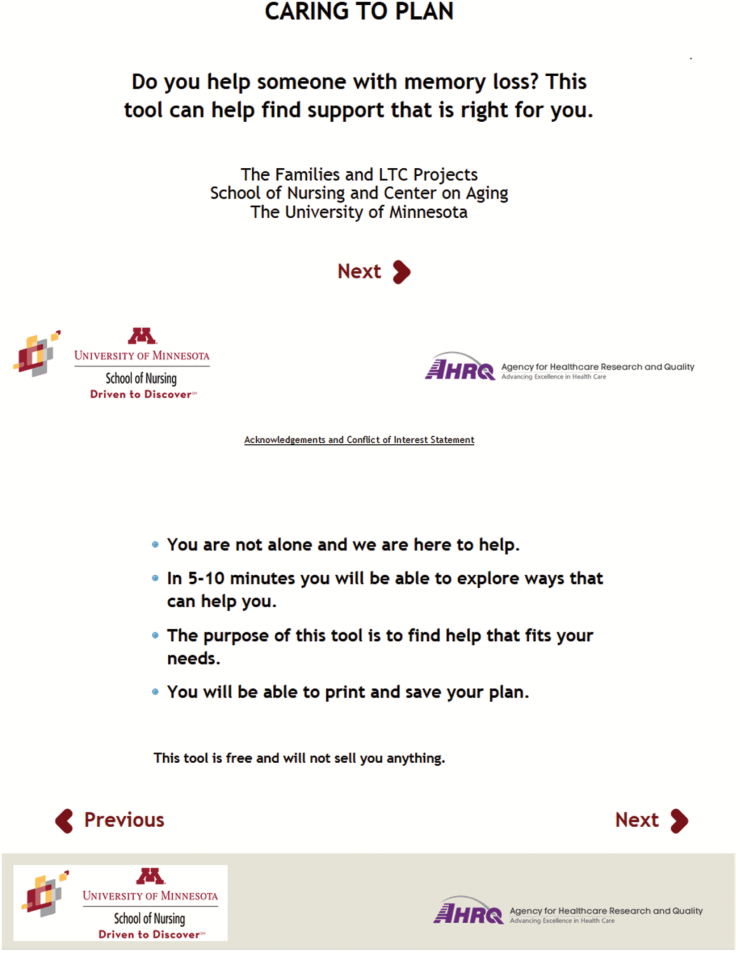

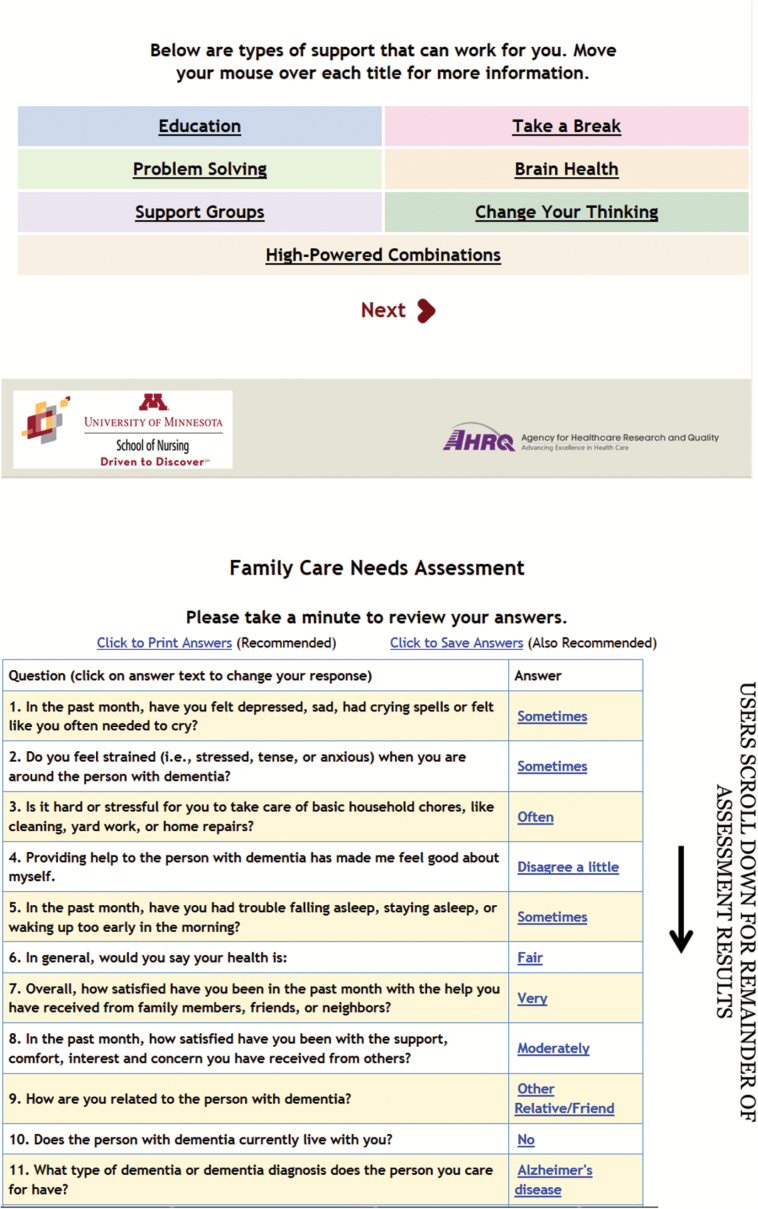

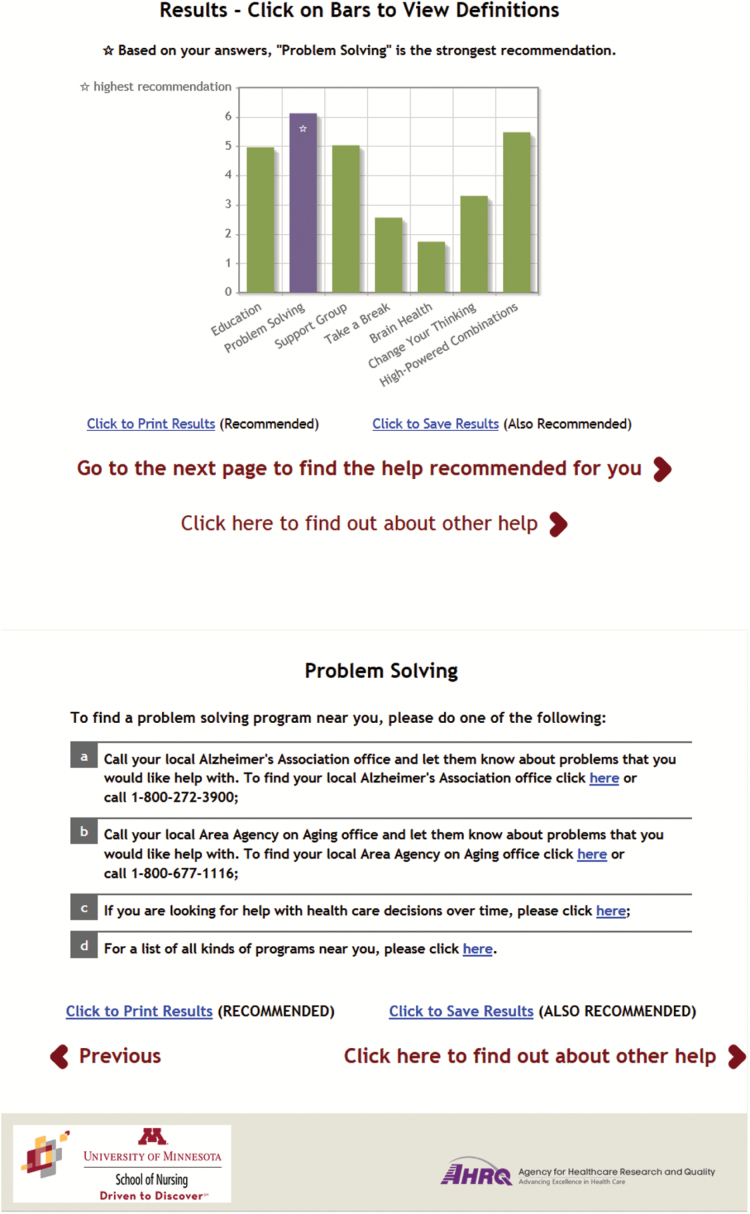

Following a brief, single-screen introduction of CtP and its purpose, CtP provides an overview of support options (i.e., intervention types) that could assist dementia caregivers. Users of CtP then complete a 20-item assessment that includes the RAM and the contextual characteristics as outlined in Table 1. Following completion of the needs assessment and calculation of risk scores based on RAM guidelines, CtP generates a tailored support recommendation based on aggregated clinical opinions. Care to Plan also provides information on where the user can find the tailored support recommendation in their area.

In the present study, a CtP counselor provided in-person guidance to dementia caregivers and facilitated CtP use and recommendation review. The counselor discussed CtP recommendations with caregivers and helped caregivers enroll in a tailored support service if so desired. If CtP users identified barriers related to transportation, a lack of financial means to access the tailored support recommendation, or a preference not to use the tailored support recommendation, the study counselor examined other recommendations to determine whether any were feasible for the dementia caregiver to utilize. In this manner, the study counselor bridged the structured options generated by the tool with dementia caregivers’ preferences so that the overall usage experience could result in feasible, tailored support.

Feasibility and Utility Testing of the CtP Prototype

J. E. Gaugler and M. Reese enrolled 21 dementia caregivers from the University of Minnesota Caregiver Registry in Fall 2014. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) the participant was the “primary” caregiver of the person with dementia (i.e., the first person called if the care recipient was in need of help); (2) the person with dementia lived in the community (i.e., at home, with the caregiver, or with other relatives) or in an independent living or assisted living facility; (3) the care recipient had a physician diagnosis of ADRD; and (4) the caregiver spent at least 8hr per week providing some type of assistance to the care recipient. M. Reese (the CtP counselor) described the project to an eligible caregiver and scheduled an in-person session where informed consent was obtained and CtP use took place. Table 2 provides descriptive characteristics of participating dementia caregivers.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Care to Plan Dementia Caregiver Users (N = 30)

| Variable | Mean (standard deviation) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | ||

| Age | 67.83 (11.17) | |

| Female | 70.0 | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 89.7 | |

| Caucasian | 90.0 | |

| Married/living with partner | 83.3 | |

| Retired | 40.0 | |

| Living children | 2.93 (2.18) | |

| Highest level of educationa | 6.80 (1.45) | |

| Household incomeb | 7.86 (2.48) | |

| Kin relationship: spouse | 60.0 | |

| Kin relationship: adult child | 40.0 | |

| Relative | ||

| Age | 80.75 (9.52) | |

| Female | 46.7 | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 96.7 | |

| Caucasian | 96.7 | |

| Married/living with partner | 73.3 | |

| Living children | 4.00 (2.79) | |

| Highest level of educationa | 5.73 (2.02) | |

| Household incomeb | 7.28 (2.46) | |

| Context of care | ||

| Time since caregiver recognized memory symptoms in person with dementia (in months) | 62.60 (29.11) | |

| Duration of care (in months) | 47.64 (33.53) | |

| Time since first visit to doctor about memory problems (in months) | 51.11 (27.74) | |

| Diagnosis: Alzheimer’s disease | 53.3 |

Notes: a1 = Did not complete junior high/middle school to 8 = graduate degree.

b1 = <$5,000 to 10 = $80,000 or more.

During a typical session, dementia caregivers completed the CtP prototype with guidance provided by the CtP counselor. Following completion of CtP (which took approximately 10–20min), the counselor collected quantitative and qualitative data to determine successful implementation. Specifically, a system review of CtP was assessed via a checklist that was administered by the counselor following dementia caregivers’ CtP use. The checklist was specially designed for feasibility and utility testing of CtP, and included 21 Likert items (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”; see Table 4) and one additional open-ended item to collect information on dementia caregivers’ perceptions of CtP performance. In addition to sociodemographic background information of the caregiver and person with memory loss, a validated measure of decision-making quality was modified and administered immediately following CtP use (item response range of 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”; decisional acceptability). Versions of this tool have been used across disease contexts to test the effectiveness of shared decision-making aids and have demonstrated strong reliability and validity (see https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html).

Table 4.

System Review Checklist of Care to Plan (Percent Agreed or Strongly Agreed)

| Care to plan aspect | Total sample (N = 30) | Prototype CtP (n = 21) | Beta CtP (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CtP was easy to use | 96.6% | 95.2% | 100% |

| The information on the introductory screen of the CtP was clear to me | 96.6% | 100% | 88.9% |

| The needs assessment that I completed on the second screen of CtP was clear | 96.6% | 95.2% | 100.0% |

| I was able to understand the service recommendations provided on the third screen of the CtP | 93.3% | 90.4% | 100.0% |

| The study counselor was helpful to me when using the CtP | 93.3% | 95.2% | 88.9% |

| I valued having the study counselor present to discuss the recommendations of the CtP | 93.3% | 90.5% | 100% |

| After using the CtP, I was able to find a service that looks as though it will meet my needs | 60.0% (26.7% reported not applicable, 16.7% indicated neutral) | 42.8% (28.6% reported not applicable; 19.0% indicated neutral) | 66.6% (22.2% reported not applicable; 11.1% reported neutral) |

| After using the CtP, I was able to find a service that looks as though it will meet my relative’s needs | 41.4% (37.9% reported not applicable, 17.2% indicated neutral) | 38.1% (33.3% reported not applicable, 23.8% indicated neutral) | 50% (50% reported not applicable) |

| There are financial constraints to me being able to use the CtP’s service recommendation | 26.6% | 23.8% | 33.3% |

| There are time constraints to me being able to use the service recommended by CtP | 40.0% | 47.6% | 22.2% |

| I am planning on using the service recommended by the CtP | 53.4% (16.7% reported not applicable; 26.7% indicated neutral) | 52.4% (19.0% reported not applicable; 23.8% indicated neutral) | 55.5% (11.1% reported not applicable; 33.3% indicated neutral) |

| The study counselor was helpful to me in coming with a plan to contact and follow-through with using the CtP service recommendation | 73.4% (20% indicated not applicable) | 66.7% (28.6% indicated not applicable) | 88.9% |

| The information provided on the CtP was clear and concise | 73.4% | 86.7% | 77.8% |

| I felt lost using the CtP | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| I wish I would have known about CtP sooner | 50.0% (26.7% reported neutral) | 47.6% (23.8% reported neutral) | 55.5% (33.3% reported neutral) |

| Transportation issues make it unlikely that I will be able to utilize the CtP’s service recommendation | 13.3% | 14.3% | 11.1% |

| The CtP provided me with a sufficient number of options to support me | 79.3% | 76.2% | 87.5% |

| The CtP provided me with a sufficient number of options to support my relative | 66.7% (13.3% indicated not applicable; 16.7% reported neutral) | 66.6% (9.5% indicated not applicable; 19.0% reported neutral) | 66.6% (22.2% indicated not applicable; 11.1% reported neutral) |

| The overall layout, text, and design of the CtP is very confusing to me. | 3.3% | 4.8% | 0% |

| I would be willing to use the CtP myself | 80.0% | 81.1% | 77.7% |

| I would recommend the CtP to others in a similar situation as I | 83.3% | 76.2% | 100% |

Note: CtP = Care to Plan tool.

As described earlier, the feasibility and utility testing of CtP was conceptually guided by the ODSF as well as the Stress Process Model. These conceptual frameworks also informed the collection of qualitative data to better ascertain how and why the CtP was deemed feasible and useful by dementia caregivers. Specifically, brief, semistructured interviews were conducted by the counselor immediately following CtP use. The semistructured interview guide is available in the Supplementary Appendix, and the questions included were based on factors relevant to both the dementia caregiving stress process as well as quality decision making in health care contexts. These interviews provided additional open-ended information on the reasons why dementia caregivers felt CtP was or was not easy to utilize, and pointed out the barriers to or facilitators of use. The semistructured interviews also provided qualitative data on whether, why, and how CtP would influence care for persons with dementia. The counselor digitally recorded each interview.

Descriptive quantitative analyses (i.e., frequencies) and thematic analyses of qualitative data were used to examine the feasibility and utility of CtP. J. E. Gaugler and M. Reese developed coding categories together with descriptors and a shared coding scheme that reflected the primary themes of the transcribed qualitative data (Morse & Field, 1995; Morse & Niehaus, 2009; Schoenberg & Rowles, 2002). Through repetition of this procedure and the use of nVivo 10, a consensus perspective on appropriate coding domains and themes were developed and then modified to identify the benefits and challenges of CtP use. In order to effectively “mix” quantitative and qualitative data, the results of descriptive empirical data on measures of CtP acceptability and utility were integrated and compared with relevant themes and quotes that emerged from the various qualitative data sources (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2010).

Community Advisory Board Feedback

During and immediately following CtP prototype testing, the Community Advisory Board provided in-depth review and comments on the initial version of CtP. Although the structure of CtP remained largely the same during the course of the project and the prototype was well received by both the Community Advisory Board and the original 21 participants, the content of CtP pages changed considerably following incorporation of the Community Advisory Board’s feedback into a beta version. Among the enhancements made included the following:

More appropriate wording, color contrast, text colors, and text positioning were implemented to help older adults read CtP more easily (per National Institute on Aging’s guidelines; see http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/making-your-website-senior-friendly#writing); and

The text on each screen (with the exception of the validated RAM assessment items) was analyzed for Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease using https://readability-score.com/ and revised to ensure that all text was at the seventh grade level or less.

Feasibility and Utility Testing of the CtP Beta Version

An additional nine dementia caregivers completed feasibility and utility testing of the beta version of CtP. The same design and procedures used when testing the prototype version of CtP were employed. Figure 1 provides select screenshots of a hypothetical adult son of a parent with Alzheimer’s disease completing the beta version of CtP.

Figure 1.

Selected screen shots of care to plan, beta version.

Results

Feasibility and Utility Findings: Prototype and Beta Versions of CtP

Qualitative Data Structure

The brief semistructured interviews took an average of 13.82min to complete (SD = 4.83min). Approximately 7hr of semistructured interviews along with written responses on the single open-ended item of the system checklist generated 132 pages of text to transcribe and analyze. Codes were identified that were later synthesized into eight main domains and a number of themes. Themes and domains were further classified into “facilitator” and “barrier” categories to illustrate CtP utility and feasibility. All themes, categories, and domains synthesized from the qualitative data are presented in Table 3 along with supportive quotes.

Table 3.

Domains and Themes: Semistructured Interviews and Open-Ended Checklist Items

| Domain | Facilitator/ barrier category | Theme | Supportive quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Believability and Appropriateness of Recommendations | Barrier | Mixed Believability and Reasonableness is Mixed More Time Needed to Consider Recommendations Care to Plan Recommendations are Lacking |

“Because when I started alone, as the caregiver, I don’t know that some of the statements would have benefitted me, because I needed more information to know—to guide and direct me as to what I needed to do.” (82-year-old Caucasian wife) |

| Facilitator | Care to Plan is Believable Care to Plan is Reasonable Care to Plan is Understandable Care to Plan Benefits Caregivers Care to Plan is Appropriate |

“Yeah. The case management rated number 2 on my graph. And again, as I started, that was the [cash] – boy, dead on. That was what I needed the most. The support group of course is of value. Taking a break, I think, is a little low. That I would probably bring up higher in my case. And again, it goes back to doing that self-care. Brain health, that’s for the individual that we’re taking care of.” (69-year-old Caucasian wife) | |

| Counselor Role | Facilitator | Counselor Involvement as a Positive Resource Care to Plan Counselor Arranged Resources Care to Plan Counselor is Needed Could use Care to Plan if Counselor is Not Present |

“But that’s where I felt it was helpful, just to have experienced professional here to say things to us, like when we say, we’re using day services twice a week. And to say, oh, maybe three times a week during a month. Or just having someone that is experienced. I think that’s helpful, because I tend to look at all the information, get overwhelmed, walk away. Like if I’m alone, I’ll be diving into all this stuff or I’ll watch all the videos, but there is, I feel like—well I don’t want to jinx the results, I’ll finish the sentence. I don’t want someone to have to transcribe this. I forgot about that until I looked at that. But basically—sorry—but basically I think a) it’s really a great tool, and people would be able to use it independently, but it was really nice having...A guide. Yeah. (laughs) Yeah, exactly. To kind of throw out some—or even just the statistics, hearing caregiving male versus female. And maybe that’s more of the counseling part. It’s one of the resources. I think it’s helpful to just, yeah, be able to talk to someone.” (77-year-old Caucasian husband) |

| Care To Plan Challenges of Use | Barrier | Content Functionality Need More Time to Review Information Needed Help Due to Lack of Clarification and Resistance to Use |

“And so even me, who is an avid reader, when I went to some of those sites where some of the recommendations were, I was like, really? I have to read through all of this to get the information that I need? Even if it was essential information, it was too much.” (60-year-old Caucasian daughter; this individual viewed the prototype version of CtP) |

| Care to Plan Ease of Use | Facilitator | Content Functionality Care to Plan Provides a Starting Point/Lifeline What Participants Liked About Care to Plan |

“There it was just right there. I know even my cousin, her dad has Alzheimer’s, has been diagnosed. And when it was first diagnosed, she said what do I do? There’s no road map. There’s nothing. And this has some categories you can look through, see what applies to you. It gives you ideas of where to start. It’s kind of like a lifeline. I wish it would have been there when I didn’t even know what rehab was.” (63-year-old Caucasian daughter) |

| Care to Plan Effects on Care for the Future | Barrier | Care to Plan Not Likely to Influence Care | “I don’t know that it would change my care exactly. It may give us other activities to do. You know. Yeah, I don’t see where the care would change much.” (77-year-old Caucasian husband) |

| Facilitator | Should Change Current Care May Change Caregiving But Contingent on Other Factors Wanted to Recommend Care to Plan to Others |

“I thought this would be something good for them to really get a hold of, so that it would help them to understand what they’re dealing with. Because they don’t have any of those resources. They are just…and her doctor is older, and obviously from what she said he hasn’t kept up. And you know, it’s just saying memory loss, but has no idea of what we’re really talking about....They really need to have something like that when they have a family meeting.” (58-year-old Latino daughter and 79-year-old Latino wife) | |

| Care to Plan Recommendations and Suggestions | Barrier | Resources and Content Usability |

“I think to have an online option too, a care coordination tool, one like care connection, or something like that, might be a nice option to include in there for providing care. Because so many caregivers are just pressed for time. So if they’ve got to call and get a ride for Mom to the doctor on a Friday, they call 10 people. The first one says call me back if you don’t find anyone. Well, working caregivers don’t have time to do all that, and it affects their jobs. So, having some other tools for care coordination is helpful. We had Dr. <name redacted> that did an evaluation on care [and action], and it did have some real positive results in catching caregivers early on in their process, but also reducing the level of stress in caregivers by using that tool.” (53-year-old Caucasian son) |

| Facilitator | No Additional Recommendations | “I think it was really very comprehensive. I don’t really see any gaps.” (78-year-old Caucasian husband) | |

| Reasons Participating in the Project | Facilitator | Altruism Engagement with Research Team or Other Resources Intrigued by Care to Plan Needed Care to Plan |

“Well, if that’s the case, it’s going to get worse. If it gets worse, I need more access to things that are on your website about people, places, phone numbers where I can get help. I want you’re help mediating the situation.” (78-year-old Caucasian wife) |

| Trajectories of Memory Loss | Facilitator | Caregiving Context Dementia Trajectory Diagnostic Context Onset of Caregiving Resources Utilized During Dementia Trajectory |

“And so it’s just a big change which is hard for me to live with, but I understand what the problems are and I am doing my best to encourage her to try.” (75-year-old Caucasian wife) |

System Review Checklist of CtP

Table 4 provides item frequency data from the CtP review checklist. The descriptive empirical results indicated that the function, usability, and clarity of CtP were well received, and that these aspects of use improved with the beta version. Users appraised the guidance and support offered by the study counselor during the session quite highly. Most users indicated that CtP-generated recommendations would potentially meet their needs.

This positive assessment of CtP was further reflected in the domains that were identified via the semistructured interviews and other qualitative data sources. For example, one qualitative domain that converged with the quantitative results in the system review checklist was the Ease of Use domain:

That’s what I felt also. You know sometimes it’s difficult, it’s almost like a different <muffled>, but it was very easy to understand. And I thought, well, someone like myself, I could really understand it. And so I thought that was very important. (79-year-old Latina wife; quote representing the Easy to Understand theme)

Well I think the choices were fairly clear and evident, and I think there was—having been through this kind of thing, you know, that the decision points are pretty much defined and there to be found, and you can pretty well, I think, tell the state of the caregiver by the responses. (83 year-old Caucasian wife; quote representing the Easy to Understand theme)

They’re labeled in a way that I can pretty much tell what they meant from the label, but then from the further descriptive information it sort of nailed it that that’s what that particular category meant. (66 year-old Caucasian husband; quote representing the Functionality theme)

Well, I think the font—very easy to absorb without glasses, and not feeling like I’m doing a lot of reading. (54-year-old Caucasian daughter; quote representing the Functionality theme)

The domain of Counselor Role suggested that although caregivers could use CtP on their own without the counselor present, they almost uniformly viewed counselor involvement in a positive light and in some instances essential:

I mean it was nice to have someone sit right next to me and do a little bit of explaining. It was great that this person knew about Lewy body dementia. I even learned more from my guide. So that was extremely helpful. I think it could be out there. People could use it. They could probably gain some knowledge, but it was much more enhanced, having a guide. (63-year-old Caucasian daughter; quote representing the Counselor Involvement as a Positive Resource theme)

Well as I kind of alluded to somewhere this morning, or afternoon, I did learn some things about my dad’s particular thing because I had a counselor available there to answer and bring that up and detect that in my situation that it was different than my mother’s in a particular way that I was totally unaware of that will help tremendously in how I internalize what’s going on. (56-year-old Caucasian son; quote representing the CtP Counselor Arranged Resources theme)

The domain Effects on Care in the Future represented how dementia caregivers perceived that CtP could or would influence the help they provided:

It’s very likely that I will seek case management. I need someplace to go, someplace where I can call, like today, I don’t have to wait until I have another support group meeting which may or may not get cancelled. (chuckle) I definitely will follow up on that one. Maybe even sooner than our next appointment. And the other things, it just depends on what they are and where we are. (76-year-old Caucasian wife; quote representing the Should Change Current Care theme)

Well the good thing about it is that now I know that I have someplace I can go. See, before I didn’t know that. So you know, now I know that, and it certainly is a place, if I’m looking for something, the first place I will go is to this, and figure it out. And if it’s not there, then I call you all. (laughs) (62-year-old African American wife; quote representing the Should Change Current Care theme)

Decisional Acceptability

Overall, the empirical item-level data collected on the modified Decisional Acceptability scale (see Table 5) demonstrated that users perceived the length, recommendations, and clarity of CtP as highly acceptable. Care to Plan provided new information to users that could potentially enhance or complement day-to-day dementia caregiving in an efficient manner. Users of the beta version of the CtP viewed the online care planning tool as more complementary to current caregiving efforts and as more useful for the earlier stages of caregiving.

Table 5.

Modified Decisional Acceptability Scale (N = 30)

| Acceptability item | Total sample (N = 30) | Prototype CtP (n = 21) | Beta CtP (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The amount of time it took to complete the CtP was: | Just right: 100% | Just right: 100% | Just right: 100% |

| The number of support services were: | Just right: 89.7% | Just right: 100% | |

| Would you have found the CtP useful when you first started caring for the person with memory loss? | Yes: 89.3% | Yes: 84.2% | Yes: 100% |

| Were the links to the organizations that provide the recommended support service helpful? | Yes: 96.4% | Yes: 94.7% | Yes: 100% |

| Would you use the CtP in the future if your caregiving situation changes? | Yes: 90.0% | Yes: 95.2% | Yes: 88.9% |

| The CtP was easy for me to use. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 96.5% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 100% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 88.9% |

| The CtP was easy for me to understand. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 100% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 100% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 100% |

| The CtP will be a tool I use repeatedly to help plan for and manage supportive services for me. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 65.5% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 65.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 66.6% |

| The recommendations from the tool will be easy to implement. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 41.3%; Neutral: 55.2% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 40.0%; Neutral: 55.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 44.4%; Neutral: 55.6% |

| The tool is better than how I usually go about finding resources and/or planning care. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 65.5% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 70.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 55.5% |

| The recommendations are compatible with my goals and priorities for caregiving. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 82.8% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 80.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 88.9% |

| The use of this tool is more cost-effective than my usual approach to finding resources and care planning. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 56.4% Neutral: 42.9% |

Agree or Strongly Agree: 55.0%; Neutral: 35.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 25.0%; Neutral: 55.6% |

| The tool increased my awareness of caregiver resources. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 86.2% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 90.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 77.8% |

| Using this tool will save me time. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 71.4% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 70.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 75.0% |

| I have confidence that the recommendations made by the CtP will help me to reduce my stress from caregiving. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 55.2% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 50.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 66.6% |

| The recommended support service will help me better care for the person with memory loss. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 72.2% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 75.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 66.6% |

| The CtP complements my usual approach to caregiving. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 79.3% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 70.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 100% |

| The recommendations given do not involve making major changes to the way I usually do things. | Agree or Strongly Agree: 62.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 55.0% | Agree or Strongly Agree: 77.8% |

| There is a high probability that using these recommendations will increase my stress. | Strongly Agree: 3.4% | Strongly Agree: 0% | Strongly Agree: 11.1% |

Note: CtP = Care to Plan tool.

The qualitative domain Believability and Appropriateness of Recommendations converged with the empirical data of the Decisional Acceptability scale by emphasizing how reasonable, appropriate, and understandable CtP was to use:

I think it has just enough categories (sic)/info - less would not be as thorough, more would be overwhelming. Nice to take a step back & look at the overall picture, very helpful. Anonymity of someone using it online would help people to be quite honest, I would think. (58-year-old Caucasian daughter, open-ended response on CtP checklist; quote representing the CtP is Appropriate theme)

M (counselor): Were the recommendations and layout understandable?

S: Yes. Yes, they were. And it shows that many of them are things that I could use help with. [However] they will make me not only an effective caregiver, but also remove—make my life less stressful. (85-year-old Caucasian husband; quote representing CtP is Understandable theme)

Similarly, the domain Believability and Appropriateness of Recommendations suggested that CtP could potentially influence the dementia caregiving situation:

I thought it was a broad spectrum. And I like that. I felt that there were several options there that, you know—and some I hadn’t really thought of. So I thought that was very good to have that as part of it. (79-year-old Latina wife; quote representing the theme How CtP Benefits Caregivers)

I had a lot—but it also reinforced and validated the choices I have made in the past. Cause in the services I had acquired—it obviously didn’t have a relationship to what I felt individually was most valuable for my own situation, but education was a big thing, and that’s something I would go along with. (56-year-old Caucasian son; quote representing the theme How CtP Benefits Caregivers)

Areas for Improvement

Although a considerable segment of the qualitative data noted the many positive aspects of CtP, one particular domain (Challenges of CtP Use) was identified that provided open-ended information as to why CtP was difficult to use, or how it could be improved:

I didn’t understand that first part, where they gave you the—and I don’t even remember the names of the six boxes <this participant was referring to the description of the seven caregiver intervention types>. I thought those were subject areas that you could pursue and learn more about. And that was a little unclear to me. (58-year-old Caucasian daughter; quote representing the theme Functionality)

For me, the topics aren’t simple. And the thought that I could even really absorb without some extra time. You know, I felt like I wasn’t—I was going, yeah, I’m going to come back to that. Yeah, I’m going to come back to that. (54-year-old Caucasian daughter; this individual viewed the prototype version of CtP; quote representing the theme Need More Time to Review Information)

Now it might be in there. I have not studied it yet, but I’d like to know more about cost, location. (62-year-old Caucasian wife; this individual viewed the prototype version of CtP; quote representing the theme Needed Help Due to Lack of Clarification and Resistance to Use)

Although some of the suggestions and criticisms regarding content, functionality, time, and clarity were addressed in the beta version of the CtP following Community Advisory Board input (as also suggested in the item-level frequency data presented in Tables 4 and 5), a number of other recommendations to improve CtP were provided. The domain CtP Recommendations and Suggestions identified several recommendations to improve CtP:

I printed out about the options. I wanted to find that. (riffling through papers) I thought—something I—and I noted this, that if there were like seminars, or—I would have liked to have seen something that if I decided, oh, this is something that’s available to me as a lay person, I think that would have been really neat. And then if there were books or things—there’s a lot out there on it. I found a couple books myself, but I would have enjoyed maybe a recommended reading. Check it out. You know I could take to the bookstore. (54 year-old Caucasian daughter; quote representing the theme Resources and Content)

One thing I think would add, when the user is looking at the [description], it was short and concise, but sometimes I want them just a little bit more, in what would be an added feature that would be just an optional thing if they wanted to, to have a one to two minute video interaction with someone sharing information about what that service was about. Very brief. It just enhances. It’s not—it may be over-cumbersome to put together, but it’s just an observation that I would find that a little bit more engaging the user and not so static. (56-year-old Caucasian son; quote representing the theme Usability)

1. Advancing to next page automatically - fewer mouse clicks, 2. Switch finger icon hover function. 3. When selecting additional description a short video (1–2min) to explain each of the services would help. 4. A side bar with descriptive icon indicating progress through the tool’s conclusion (56-year-old Caucasian son; open-ended data from checklist; quote representing the theme Usability)

Discussion

The integrated qualitative and quantitative data demonstrated the feasibility and potential utility of CtP. Overall, users emphasized the clarity of the information and recommendations provided, which tended to improve following the enhancements suggested by the Community Advisory Board. Dementia caregivers felt that CtP was simple and easy to understand in terms of its content. Users indicated that the visual layout and the streamlined text provided on each screen of CtP were effective in this regard. Perhaps most critically, the recommendations generated by CtP were perceived as potentially meeting the needs of users. The tool provided new information that could benefit and/or supplement the support and services dementia caregivers were currently relying upon. Users indicated that the number of options (e.g., the seven types of caregiver interventions/services) was difficult to remember, and that there was a need to review these services following completion of CtP. Users also wondered about the cost of various services. Suggestions to improve CtP included a reading list, brief video introductions about each service, and several usability enhancements (e.g., advancing to subsequent pages automatically).

The strong feasibility and utility of CtP suggests broad-based application of this online tool to support dementia caregivers. For example, real-world use of the tool could include support providers in area agencies on aging using CtP with dementia caregivers as a way to: (1) screen dementia caregivers as to their perceived stress, depression, and self-risk (as CtP relies on a brief, validated assessment screen to do so: the RAM) and (2) utilize one or more recommendations as the basis to discuss next steps regarding tailored support that could potentially benefit a dementia caregiver. The CtP could also operate as a standalone, online tool that is embeddable in blogs and other web-based informational resources that dementia caregivers could access when identifying and locating tailored support recommendations in their communities. Given the robust solicitation of recommendations (see aforementioned and Gaugler et al., 2015) and the grounding of CtP in service types that have generated evidence-based research on their efficacy (Gitlin et al., 2015; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006), we believe CtP can extend current practice. Specifically, CtP could help professional support providers identify and recommend tailored support through the use of this brief, efficient, and easy-to-understand web-based platform.

Care to Plan also has the potential for fairly rapid dissemination. As described earlier, over 400 professional, clinical, and scientific experts participated in rating hypothetical dementia caregiver scenarios; these ratings served as the basis for the tailored support recommendations of the CtP (Gaugler et al., 2015). We plan to disseminate CtP to these individuals following its final refinement, as many of these experts work in community organizations or clinical programs throughout the United States that provide direct services to dementia caregivers. In this manner, dementia caregivers would have access to CtP and use it; we hope to build several simple and brief data collection modules in CtP itself to collect ongoing utility data during its dissemination. Care to Plan will have an ongoing online presence to assist dementia caregivers. It is our aim to have CtP publically available at no charge to users. This will further enhance the potential reach of CtP beyond the evaluative parameters of this or future projects. We will also adopt a broad web location strategy. In addition to locating CtP on its current site, the online recommendation tool could link to supporting organizations’ web pages as well as a number of popular blogs. These strategies will allow for wide dissemination of CtP and will also facilitate future evaluations.

There are limitations that are important to note. As this is a feasibility study, it is not clear if CtP actually influences the support caregivers’ utilize, whether caregivers are satisfied or confident with their decision to utilize the tailored support recommendation, and if linking dementia caregivers to a tailored support recommendation improves caregiver and perhaps care recipient outcomes. As emerging intervention types are currently amassing higher quality evidence supporting their use (e.g., relaxation techniques; see Gitlin & Hodgson, 2015; Gitlin et al., 2015; The Alzheimer’s Association, 2015; Whitebird et al., 2013), it is possible that the seven intervention types included in the CtP may require updating to better reflect the state-of-the-art in dementia caregiver intervention science. The location of services as currently presented in CtP is quite broad in order to accommodate users throughout the United States. Updating the recommendations to include local resources and organizations may further enhance CtP for dementia caregivers in specific states and regions.

The goal of CtP is to help families and unpaid nonrelatives who care for individuals with memory loss identify tailored support that could benefit them in their particular situation. A finding that emerged from this study is that although many dementia caregivers are capable of using CtP on their own and would not necessarily require assistance when doing so, the presence of a counselor or similar support professional may greatly enhance the experience. It is important to note that the counselor, while collecting empirical and open-ended information on the feasibility and utility of CtP, also provided direct assistance and guidance to dementia caregivers when needed and/or requested. Users indicated that the inclusion of a facilitator to “walk” dementia caregivers through the various screens and choices presented in CtP optimized the tool’s performance. Specifically, dementia caregivers felt that having the counselor present helped to make CtP “come alive” and allowed users to better reflect on how the tool and its recommendations were immediately relevant to their own care situations. Whether the presence of a counselor is critical to CtP reaching its full potential will be the focus of future evaluation (e.g., a randomized controlled evaluation that compares a CtP + counselor and a CtP only user group with dementia caregivers who do not receive CtP over a designated period of time).

As the extensive literature on dementia caregiving makes clear (Gaugler et al., 2014; The Alzheimer’s Association, 2015), the process of providing help to someone with memory loss is stressful, life-changing, and often fraught with complex family dynamics. A support professional could help guide dementia caregivers through this cauldron of distress to use CtP successfully. For these reasons, we believe that CtP is best deployed as a tool for area agencies on aging or similar organizations’ caregiver support staff. These staff may provide more structured, organized guidance when reviewing and completing the tool in a screen-by-screen fashion than families could achieve on their own. A challenge, and one noted by others who have developed web-based long-term care decision-making tools (Kane et al., 2007), is the need to engage professionals to help integrate CtP in their own standard processes. If this occurs, professionals could help address the lack of local dementia caregiver services by identifying available tailored support that could potentially meet the needs and preferences of CtP users.

To this end, we have begun developing a CtP counselor manual that provides screen-by-screen guidance to care managers, case managers, or other professionals who would potentially guide a dementia caregiver through CtP use and referral. We would anticipate that, in addition to the increased confidence and self-efficacy dementia caregivers may have when using CtP in the presence of a facilitator, professionals themselves who use the CtP may offer more consistent referral and support than current practice (Kane et al., 2007). A critical issue inherent in this assumption is whether professional support providers believe that the structured approach of CtP adds value to their current practice. A common concern that many professionals often raise is the length of assessment instruments to guide the selection of community-based long-term care services; CtP, which is simple to use and streamlined to increase its utility, potentially resolves such issues. By describing, identifying, and prioritizing tailored support and linking families to these resources, CtP could help to improve the care planning process for dementia caregivers.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by grants K02AG029480 (National Institute on Aging), R03HS020948 (Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality), and K18HS022445 (Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality) to Dr. J. E. Gaugler.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Robert Kane for his guidance and Dr. Julie Bershadsky for analytic support. The authors would also like to thank the family caregivers who participated as well as the Community Advisory Board of this project: Sara Barsel, Frank Bennett, Judy Berry, Venoreen Browne-Boatswain, Kirsten Cruikshank, Kathleen Dempsey, Susan Eckstrom, Emily Farah-Miller, Karen Gallagher, John Hobday, Lori LaBey, Danielle Lesmiester, Roschelle Manigold, Connie Marsolek, Teresa McCarthy, Siobhan McMahon, A. Richard Olson, Jane Olson, Mary O’Neill, James Pacala, Maria Reyes, Raquel Rodriquez, Patricia Schaber, Kathleen Schaefers, Donna Walberg, George Willard, and Deb Taylor.

References

- Anderson K. A. Nikzad-Terhune K. A., & Gaugler J. E (2009). A systematic evaluation of online resources for dementia caregivers. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet, 13, 1–13. doi:10.1080/15398280802674560 [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel C. S. Pearlin L. I. Mullan J. T. Zarit S. H., & Whitlatch C. J (1995). Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgio L. D. Collins I. B. Schmid B. Wharton T. McCallum D., & Decoster J (2009). Translating the REACH caregiver intervention for use by area agency on aging personnel: the REACH OUT program. The Gerontologist, 49, 103–116. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., & Plano Clark V. L (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S. J. Gitlin L. N. Schulz R. Zhang S. Burgio L. D. Stevens A. B.,…Gallagher-Thompson D (2009). Development of the risk appraisal measure: A brief screen to identify risk areas and guide interventions for dementia caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1064–1072. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02260.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., & Kane R. L (Eds.). (2015). Family caregiving in the new normal. (1st ed.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E. Potter T., & Pruinelli L (2014). Partnering with caregivers. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 30, 493–515. doi:S0749-0690(14)00038-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Westra B. L., Kane R. L. (2015). Professional discipline and support recommendations for family caregivers of persons with dementia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota School of Nursing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E. Yu F. Krichbaum K., & Wyman J. F (2009). Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical Care, 47, 191–198. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. N., & Hodgson N (2015). Caregivers as therapeutic agents in dementia care: The evidence-base for interventions supporting their role. In Gaugler J. E., Kane R. L. (Eds.), Family caregiving in the new normal (pp. 305–356). Philadelphia: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-417046-9.00017-9 [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L. N. Marx K. Stanley I. H., & Hodgson N (2015). Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. The Gerontologist, 55, 210–226. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgeman M. M. Durkin D. W. Sun F. DeCoster J. Allen R. S. Gallagher-Thompson D., & Burgio L. D (2009). Testing a theoretical model of the stress process in Alzheimer’s caregivers with race as a moderator. The Gerontologist, 49, 248–261. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L. Bershadsky B., & Bershadsky J (2006). Who recommends long-term care matters. The Gerontologist, 46, 474–482. doi:10.1093/geront/46.4.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L. Boston K., & Chilvers M (2007). Helping people make better long-term-care decisions. The Gerontologist, 47, 244–247. doi:10.1093/geront/47.2.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman M. S., & Bartels S. J (2014). Translating research into practice: Case study of A community-based dementia caregiver intervention. Health Affairs, 33, 587–595. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery R. J. Kwak J. Kosloski K., & O’Connell Valuch K (2011). Effects of the TCARE® intervention on caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: Preliminary findings from a randomized controlled study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 640–647. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M., & Field P. A (1995). Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M., & Niehaus L (2009). Mixed method design: Principle and procedures (developing qualitative inquiry). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols L. O. Martindale-Adams J. Burns R. Zuber J., & Graney M. J (2014). REACH VA: Moving from translation to system implementation. The Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I. Mullan J. T. Semple S. J., & Skaff M. M (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics, 18, 577–595. doi:10.1017/S1041610206003462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg N. E., & Rowles G. D (2002). Qualitative gerontology: A contemporary perspective. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- The Alzheimer’s Association. (2015). 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11, 332–384. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierlo L. D. Meiland F. J. Van der Roest H. G., & Droes R. M (2012). Personalised caregiver support: Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in subgroups of caregivers of people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 1–14. doi:10.1002/gps.2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitebird R. R., Kreitzer M., Crain A. L., Lewis B. A., Hanson L. R., Enstad C. J. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for family caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist, 53, 676–686. doi:10.1093/geront/gns126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.