Abstract

Motivation: Permutational non-Euclidean analysis of variance, PERMANOVA, is routinely used in exploratory analysis of multivariate datasets to draw conclusions about the significance of patterns visualized through dimension reduction. This method recognizes that pairwise distance matrix between observations is sufficient to compute within and between group sums of squares necessary to form the (pseudo) F statistic. Moreover, not only Euclidean, but arbitrary distances can be used. This method, however, suffers from loss of power and type I error inflation in the presence of heteroscedasticity and sample size imbalances.

Results: We develop a solution in the form of a distance-based Welch t-test, , for two sample potentially unbalanced and heteroscedastic data. We demonstrate empirically the desirable type I error and power characteristics of the new test. We compare the performance of PERMANOVA and in reanalysis of two existing microbiome datasets, where the methodology has originated.

Availability and Implementation: The source code for methods and analysis of this article is available at https://github.com/alekseyenko/Tw2. Further guidance on application of these methods can be obtained from the author.

Contact: alekseye@musc.edu

1 Introduction

The PERMANOVA test (Anderson, 2001), has been proposed for use in numerical ecology to test for the location differences in microbial communities. The relationships between these communities are typically described by ecological distance metrics (e.g. Jaccard, Chi-Squared, Bray-Curtis) and visualized through dimension reduction (also referred to as ordination in numerical ecology literature). The PERMANOVA permutation test based on (pseudo) F statistic computed directly from distances is a widely accepted means of establishing statistical significance for observed patterns. This test and the extension of this paper are related to the multivariate Behrens-Fisher problem (Krishnamoorthy and Yu, 2004) of testing the difference in multivariate means of samples from several populations. The underlying statistics for both distance-based tests are related to the Hotelling T2 statistic. The PERMANOVA is more general in allowing for more than two populations to be compared simultaneously. The distance-based geometric approach; however, forgoes the need to estimate the covariance matrices. The cost of these geometric approaches is that they only provide omnibus tests, which are unable to make inferences about individual components of the multivariate random vectors tested.

With the revived interest in numerical ecology fueled by the availability of DNA sequencing-based high-throughput microbial community profiling, i.e. microbiomics, the PERMANOVA test is enjoying a new wave of popularity. Several, cautionary articles have been published noting the undesired behavior of the test in heteroscedastic conditions (Warton et al., 2012). A definitive principled solution to this issue is still lacking, however. The consensus is to ascertain the presence of heteroscedasticity using an additional test (e.g. PERMDISP; Anderson, 2006; Anderson et al., 2006) in case of positive PERMANOVA results and to report both with a disclaimer that the attribution of positive PERMANOVA test to location or dispersion differences cannot be made whenever both tests yield positive results. In reality, the exactly matching multivariate spread between factor levels can rarely be assumed and the robustness of PERMANOVA to violations of homoscedasticity has not been characterized empirically.

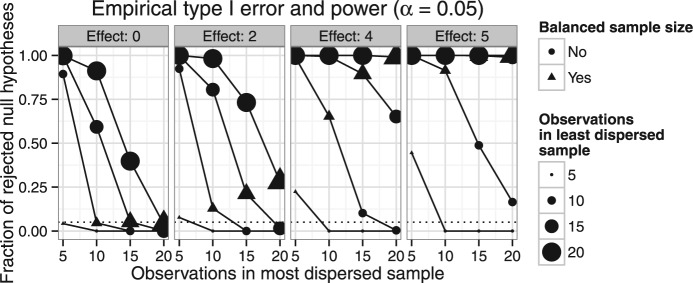

1.1 Performance of PERMANOVA in heteroscedastic data

We demonstrate the adverse behavior of PERMANOVA in unbalanced heteroscedastic case via a simulation. Let sample one consists of observations from 1000-dimensional uncorrelated multivariate normal distribution, where each component is standard normal (mean 0 and SD 1). Sample two is likewise 1000-dimensional uncorrelated multivariate normal with means equal to fraction of the desired effect size and standard deviation equal 0.8. Thus sample one has 20% more multivariate spread than sample two. We set the effect size to 0, 2, 4 and 5. We compute the corresponding Euclidean distances for use with PERMANOVA test, using its implementation in the adonis() function of the R (R Core Team, 2015) package vegan (Oksanen et al., 2015). We repeat the simulation 1,000 times for each set of parameters and compute the average rejection rate at α = 0.05. Figure 1 summarizes the type I error and power characteristics for this design with varying sample sizes. First, note that the type I error (left most box, where effect size equal to 0) is only correct when the samples are balanced. Whenever, the number of observations in the most dispersed sample is less than that in the other sample the type I error is inflated. In the opposite case, hardly any rejections are made. When there is true location difference between the samples (effect size greater than 0), the power curves have non-typical sigmoidal shapes corresponding to the loss of power with increasing number of observations in the overdispersed sample. However, the power curves under balanced sample sizes (triangles) are typical. Note that if PERMDISP is used to ascertain heteroscedasticity, only type I error inflation can be detected, while the dramatic loss of power cannot be corrected. When the samples are simulated under homoscedastic scenario, typical values of type I error (around nominal significance threshold) and power characteristics are observed (Table 1). These observations suggest that PERMANOVA is robust to violations of either the homoscedasticity or the balanced sample size assumptions, but not both. Simultaneous violation of both assumptions leads to loss of type I error control and loss of power.

Fig. 1.

Type I error and power characteristics of the PERMANOVA test with potentially unequal sample sizes. The headers of the boxes indicate the simulated effect size 0 (where type I error rate is determined), 2, 4 and 5. The size of the points corresponds to the number of observations in the least dispersed sample. Points, where the sample sizes are balanced, are indicated by triangles. Plot of a method with ideal type I error characteristics (left box) will be a horizontal line at the significance threshold α = 0.05. When effect size is greater than 0, the plots show the power characteristics. Plot of a method with ideal power will be a horizontal line at 1.0, corresponding to perfect power and no type II error

Table 1.

Fraction of rejected null hypotheses by PERMANOVA with simulated homoscedastic data and varying number of observations in two samples

| Type I error |

Power, efficient size = 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 5 | 0.046 | — | — | — | 0.072 | — | — | — |

| 10 | 0.041 | 0.059 | — | — | 0.096 | 0.134 | — | — |

| 15 | 0.051 | 0.049 | 0.047 | — | 0.089 | 0.135 | 0.172 | — |

| 20 | 0.049 | 0.047 | 0.059 | 0.050 | 0.106 | 0.134 | 0.167 | 0.225 |

2 Approaches

In this article, we provide a definitive and principled two-sample solution to heteroscedasticity-related type I error inflation and loss of power with PERMANOVA. We do this by demonstrating that instead of the F-statistic utilized by PERMANOVA, a distance-based Welch t-statistic can be computed. We derive this Welch t-statistic from pairwise distance matrix. We perform an empirical study of type I error and power properties of this statistic in the permutation testing setup. Finally, we perform two applications of this new test in discovery data analysis and small clinical study scenarios.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Univariate case

In a two-sample , independent and identically distributed univariate case, we are concerned with assessing the difference between the population means of the underlying distributions from which xi’s and yi’s are drawn. The square of the corresponding Welch t-statistic is

| (1) |

where and are the usual estimates of the sample mean and variance for X, with and defined similarly for Y. Observe that the sum of square differences from the mean, which appears in the expression for sample variance, can be written in terms of the sum of squares of pairwise differences.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

This allows us to write the variance as

| (7) |

where denotes double summation . Thus the denominator of (1) can be expressed in terms of only squares of pairwise differences between data points. Likewise, the difference of the means in the numerator of (1) can be expressed in terms of just the pairwise differences. Let be the concatenation of the observations in X and Y, then is the sample mean of Z. We can write:

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

Now consider the first term of Equation (16).

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

The combined contribution of the first terms of (21) from and terms of (16) can be written in terms of pairwise differences of zi’s:

| (22) |

This and Equations (6), (16) and (21) imply that the square of mean difference is expressable in terms of sums of squares of pairwise differences:

| (23) |

Finally, Equations (7) and (23) can be put together to form the Welch t-statistic (1) in terms of only the squares of the pairwise differences.

The point differences can be thought of as distances. Let be the matrix of absolute pairwise differences, . The elements of D are in fact Euclidean distances between data points in one-dimension. Now the sums of squares can be expressed in terms of ’s:

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

In terms of squares of pairwise distances the statistic can be written as

| (27) |

Note that Equation (24) expresses total sums of squares, and Equations (25) and (26) express the within sample sums of squares in terms of distances, while the term in square brackets of Equation (23) corresponds to between group sums of squares. These are the same terms that appear in the PERMANOVA two-sample (pseudo)F statistic computation. Here we write the PERMANOVA statistic for the two sample case and arbitrary nx and ny:

| (28) |

It is easy to check that when the sample sizes are balanced, nx = ny, or within group sums of squares are equal, , then FA and differ by a multiplicative factor that only depends on nx and ny. This means that inference under the two statistics will be different when both unbalanced sample sizes and heteroscedasticity is present, which may help correct the adverse behavior of PERMANOVA observed in Figure 1 and Table 1.

3.2 Multivariate extension

Next we examine a multivariate extension of the distance-based statistic. Let the observations be multivariate vectors, , where and are of arbitrary dimension m. As before, let be the pairwise matrix of Euclidean distances . We use these distances in place of their univariate counterpart to compute and FA. By extension arbitrary distances (e.g. Jaccard, Bray-Curtis etc.) can be used for this purpose. Note that in contrast to the PERMANOVA statistic the distance-based explicitly accounts for potentially unbalanced number of observations and differences in multivariate spread in the two samples.

3.3 Permutation test

The exact distribution of the multivariate distance-based statistic is dependent on many factors, such as the dimensionality of the underlying data, the distributions of these random variables, the exact distance metric used etc. To make a practical general test, we use permutation testing to establish the significance. To do so we compute on k permutations, , for , of the original data. The estimate of significance is obtained as the fraction of times the permuted statistic is greater than or equal to , i.e. . Here designates the indicator function. In practice, the distance matrix D does not need to be recomputed with each permutation, as it is sufficient to just permute the sample labels. This permutation procedure is used by the original PERMANOVA method and is a standard application of permutation testing.

3.4 Distance-based effect size

The ability to compute pseudo-variances and square mean difference using just pairwise distances allows for estimation multivariate effect sizes in terms of familiar to statisticians Cohen’s d. Using derivations (7) and (23) we write

| (29) |

The positive square root of d2 provides an estimate of the absolute value of the distance Cohen's d and adds another potentially interesting effect size measurement for multivariate analysis, in addition to the recently proposed (Kelly et al., 2015).

4 Results

4.1 Simulation results

In this section, we extend the simulation study in the Introduction section to compare the performance of PERMANOVA and . Again, the nx observations in sample one are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) , the ny observations in sample two are i.i.d. , where ε controls the effect size and f controls the degree of multivariate spread differences (fraction SD) between the two samples. For each set of nx, ny, ε, and f we simulate 1000 independent datasets. For each dataset we compute the p-values using permutation testing with PERMANOVA and statistics. We calculate the fraction of rejected null-hypothesis with each test at significance level .

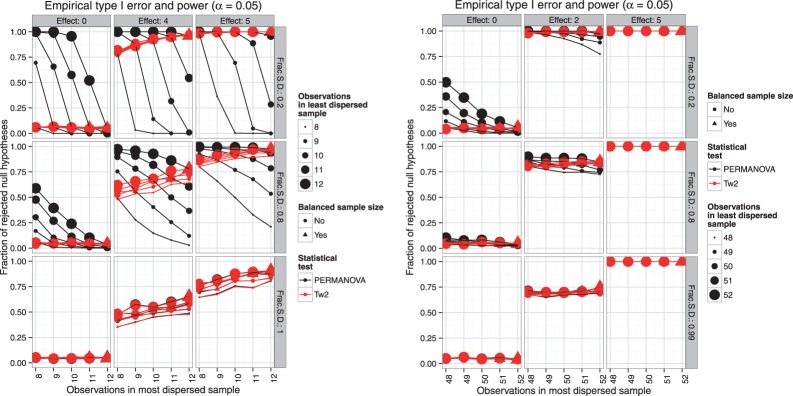

First, we consider a broad scan over the sample sizes . Representing, case to control (or treated to untreated) ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3 and 1:4 with relatively small overall sample size. Under the null hypothesis maintains the prescribed rejection rate for all examined levels of heteroscedasticity (Fig. 2 first column). As we have seen in the Introduction, in the unbalanced heteroscedastic case the PERMANOVA exhibits inflated type I errors (Fig. 2 first column). As demonstrated in scenarios where , unlike PERMANOVA, has greater power to detect differences as the sample sizes increase (Fig. 2 columns two and three, rows one and two). The power curves for the two tests are similar when multivariate spread in the two samples is the same (Fig. 2 bottom row columns two and three). When it is not, however, the curves intersect at approximately the point where the sample sizes in the two groups are balanced (triangles). This suggests that overcomes the problematic behavior of PERMANOVA and has similar power under the homoscedastic design (Fig. 2 bottom row) and when sample sizes are balanced (Fig. 2 triangles).

Fig. 2.

Empirical type I error and power characteristics of PERMANOVA (black) and (red). The effect sizes vary in columns of panels. Effect size 0 corresponds to the case where the null hypothesis is true and the plots demonstrate the type I error. Plot of a method with ideal type I error characteristics will be a horizontal line at the significance threshold α = 0.05. When effect size is greater than 0, the plots show the power characteristics. Plot of a method with ideal power will be a horizontal line at 1.0, corresponding to perfect power and no type II error. The degree of heteroscedasticity varies along the rows and is represented in terms of ratio of the standard deviations (Frac SD) between two samples. The bottom row corresponds to homoscedastic scenario, the top and middle rows show high and medium heteroscedasticity scenarios, respectively. The number of observations in the least dispersed sample is indicated by the size of the point and the balanced samples are identified by triangles

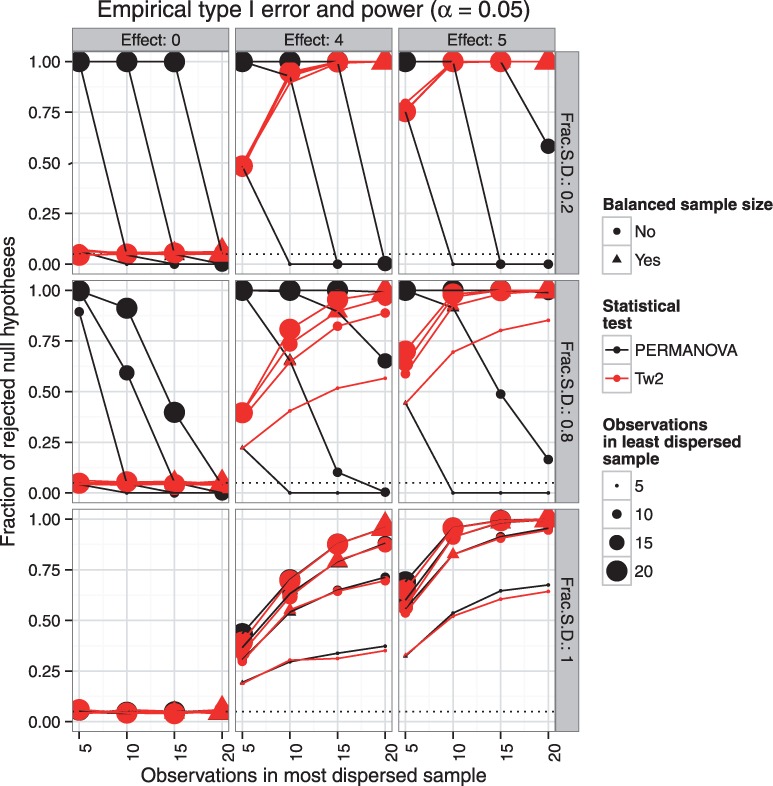

Imagine an experiment in which an investigator aims to compare 10 observations in each group. For reasons beyond their control (e.g. animal dies, subjects drop from protocol, unequal gender ratio) the resulting sample sizes at the end of the experiment may not exactly be 10 versus 10. These conditions are encountered in many common discovery type studies. We examine the effect of heteroscedasticity for PERMANOVA and under these conditions. We perform a similar comparison for sample sizes in the vicinity of 50, corresponding to sample sizes in a typical small clinical study. As we have seen previously, when the multivariate spread in the two samples is the same or similar, the power curves for PERMANOVA and overlap (Fig. 3a and b bottom row). With sample sizes around 10 the violation of homescedasticity leads to loss of power (Fig. 3a columns two and three and rows one and two) and inflated type I errors (Fig. 3a first column rows one and two) with PERMANOVA relative to. With the sample size increasing to approximately 50, PERMANOVA becomes more robust, while the traces of the issue still remain when the effect size is small (Fig.3b second column). Likewise, at these sample sizes the type I error inflation is still present when the unbalance is more extreme and heteroscedasticity is large (Fig. 3b top left). Overall, has better or similar type I error and power characteristics to PERMANOVA and should be recommended in all two-sample designs.

Fig. 3.

Empirical type I error and power characteristics of PERMANOVA (black) and (red) tests with varying effect size, degree of heteroscedasticity and number of observations in two samples, for sample sizes typical for (a) a discovery study or (b) a small clinical study. The effect sizes vary in columns of panels. Effect size 0 corresponds to the case where the null hypothesis is true and the plots demonstrate the type I error. Plot of a method with ideal type I error characteristics will be a horizontal line at the significance threshold α = 0.05. When effect size is greater than 0, the plots show the power characteristics. Plot of a method with ideal power will be a horizontal line at 1.0, corresponding to perfect power and no type II error. The degree of heteroscedasticity varies along the rows and is represented in terms of ratio of the standard deviations (Frac SD) between two samples. The bottom row corresponds to homoscedastic scenario, the top and middle rows show high and medium heteroscedasticity scenarios, respectively. The number of observations in the least dispersed sample is indicated by the size of the point and the balanced samples are identified by triangles

4.2 Application examples

We apply the to two previously published datasets on microbiome differences in the gut (Cho et al., 2012) and on the skin (Alekseyenko et al., 2013). In both cases we compute the distances using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, . For each comparison, we compute the P-values with 100 000 permutations under PERMANOVA and and quantify the corresponding effect size using and distance Cohennc d. The difference in the multivariate spread is measured as the ratio of mean distances within compared groups.

4.2.1 Sub-therapeutic antibiotic treatment microbiome dataset

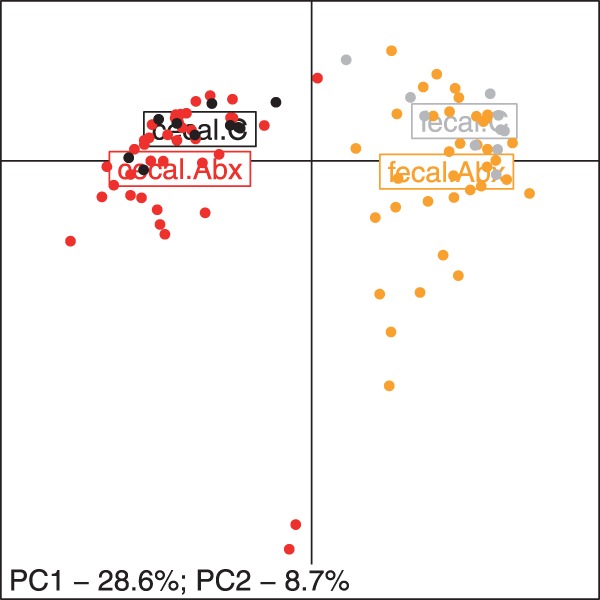

The gut microbiome dataset consists of measurements of abundances of gut microbes obtained from mice that either received a prescribed antibiotic in their drinking water or none (C). Samples were obtained from two locations of the gut of these mice (cecal and fecal). The target number of samples per location was 10; however, several fecal samples could not be analyzed for technical reasons. Table 2 summarizes the results of the analysis of these data. At a commonly used significance threshold of α = 0.05, both PERMANOVA and agree in the statistical decision. However, if we were to use a more stringent α = 0.01, the comparison of the control microbiota against microbiota of all the mice receiving antibiotic would not be deemed significant under PERMANOVA, while the P-values under are below the significance threshold. The estimated effect size, d, for C. versus All abx. comparison in cecal and fecal samples are 1.28 and 1.42, respectively. Both of these are considered large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988) and given adequate sample sizes would be deemed highly significant. Moreover, when we examine these data using principal coordinates analysis, the separation of the group centroids is evident (Fig. 4). The largest separation along PC1 is observed for the location (fecal versus cecal). The antibiotic versus control groups are separated along PC2. Note that for cecal samples the comparison of the controls against each of the antibiotic treatment groups individually is significant and similar for both tests. This is expected because the design is balanced in these tests.

Table 2.

Comparison of PERMANOVA and on mouse gut microbiome dataset

| Cecal microbiome |

Fecal microbiome |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P-values |

P-values |

|||||||||||

| Comparison | N obs. | d | PERMANOVA | N obs. | d | PERMANOVA | ||||||

| C. versus all abx. | 10 versus 40 | 1.4 | 0.22 | 1.21 | 0.040 | 0.0001 | 10 versus 36 | 1.4 | 0.29 | 1.34 | 0.015 | 0.0014 |

| C. versus penicillin | 10 versus 10 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 1.90 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | 10 versus 9 | 1.1 | 0.07 | 1.94 | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| C. versus vancomycin | 10 versus 10 | 1.8 | 0.08 | 2.26 | 0.00009 | 0.0001 | 10 versus 9 | 1.6 | 0.21 | 2.70 | 0.00001 | 0.00002 |

| C. versus tetracycline | 10 versus 10 | 1.2 | 0.12 | 2.05 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 10 versus 10 | 1.0 | 0.07 | 1.89 | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| C. versus vancomycin + tetracycline | 10 versus 10 | 1.1 | 0.10 | 1.97 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 10 versus 8 | 1.4 | 0.11 | 2.24 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

Fig. 4.

Principal coordinates analysis of sub-therapeutic antibiotic treatment data. Points correspond to the individual observations in cecal control (black), cecal antibiotics (red), fecal control (gray), and fecal antibiotic (orange) groups. The centroid of each group is marked by the box with the group labels

4.2.2 Skin microbiome in psoriasis dataset

The skin microbiome dataset consists of observations of skin microbial abundances from control subjects and from psoriasis subjects, who contribute two samples from a lesion site and from symmetrical unaffected site. PERMANOVA and tests produce similar significance values and inferences (Table 3), which is owed to the fact that the multivariate spread is similar in all conditions, and sample sizes are larger and closer to being balanced.

Table 3.

Comparison of PERMANOVA and on human skin microbiome dataset

|

P-values |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | N obs. | d | PERMANOVA | |||

| Control versus Lesion | 49 versus 51 | 1.07 | 0.014 | 0.77 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 |

| Control versus Unaffected | 49 versus 51 | 1.04 | −0.0006 | 0.60 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Lesion versus Unaffected | 51 versus 51 | 0.97 | 0.004 | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

5 Discussion

By derivation inherits the characteristics of the univariate unequal variance Welch t-test. That test is recommended as a replacement for pooled variance t-test in all circumstances. Testing for unequal variances by methods, such as PERMDISP, is not recommended before a choice of the primary test is made. The main disadvantage of the Welch’s t-test compared with ANOVA is potential loss of robustness when violations of normality are present (Levy, 1978). This issue, however, rests on the limiting distributions of the tests. In our case, the inference is obtained by permutation testing, which alleviates this concern. Thus should also become a first line replacement for PERMANOVA in simple two-sample case.

Two-sample scenario is a common experimental design, but a general solution for k-level factors is still desirable. The behavior of PERMANOVA under heteroscedastic conditions with k-level factors have not been examined, but is suspected to suffer from similar shortcomings as in the two sample case. When heteroscedasticity is suspected, several remedial strategies can be implemented. First, a variance stabilizing transformation can be applied to the data to remove heteroscedasticity (McMurdie and Holmes, 2014). If transformation of the data is not desirable for any reason, other strategies could include developing specialized sub-sampling and permutation-based strategies. For example, the data could be re-sampled m times at balanced sample sizes and an average PERMANOVA statistic computed . This statistic could then be compared with the null distribution generated by permuting the sample labels r-times and computing the re-sampled , where . The significance can be determined by using regular permutation testing approach to compare the number of times the obtained statistic is more extreme than those observed under the null, i.e. . This method ensures that the groups are balanced in each comparison, but may still lead to loss of power due to decreased effective sample size in each sub-sampled comparison. This approach is reported here as a suggestion that needs further development and evaluation before in can be implemented in practice. The final strategy for analysis of data with arbitrary number of levels could involve the application of to only relevant pairwise comparisons with appropriate multiple comparison controls in place.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Ali Shojaee Bakhtiari, Dr Beth Wolf and three anonymous reviewers for reviewing and suggesting valuable improvements to this work.

Funding

A.V.A. is supported in part by the NIH through 5R01CA16496402 from the NCI.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Alekseyenko A.V. et al. (2013) Community differentiation of the cutaneous microbiota in psoriasis. Microbiome, 1, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.J. (2001) A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Aust. Ecol., 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.J. (2006) Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics, 62, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.J. et al. (2006) Multivariate dispersion as a measure of beta diversity. Ecol. Lett., 9, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I. et al. , (2012) Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature, 621–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B.J. et al. (2015) Power and sample-size estimation for microbiome studies using pairwise distances and permanova. Bioinformatics, 31, 2461–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy K., Yu J. (2004) Modified nel and van der merwe test for the multivariate behrens-fisher problem. Stat. Prob. Lett., 66, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Levy K.J. (1978) An empirical comparison of the anova f-test with alternatives which are more robust against heterogeneity of variance. J. Stat. Comput. Simul., 8, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie P.J., Holmes S. (2014) Waste not, want not: Why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol., 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J. et al. (2015) vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.3-0.

- R Core Team (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Warton D.I. et al. (2012) Distance-based multivariate analyses confound location and dispersion effects. Methods Ecol. Evol., 3, 89–101. [Google Scholar]