Abstract

Motivation: Hashing has been widely used for indexing, querying and rapid similarity search in many bioinformatics applications, including sequence alignment, genome and transcriptome assembly, k-mer counting and error correction. Hence, expediting hashing operations would have a substantial impact in the field, making bioinformatics applications faster and more efficient.

Results: We present ntHash, a hashing algorithm tuned for processing DNA/RNA sequences. It performs the best when calculating hash values for adjacent k-mers in an input sequence, operating an order of magnitude faster than the best performing alternatives in typical use cases.

Availability and implementation: ntHash is available online at http://www.bcgsc.ca/platform/bioinfo/software/nthash and is free for academic use.

Contacts: hmohamadi@bcgsc.ca or ibirol@bcgsc.ca

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Hashing is a common function across many informatics applications, and refers to mapping an input key value of arbitrary size to an allocated memory of predetermined size. Among other uses, it is an enabling concept for rapid search operations, and forms the backbone of Internet search engines. In bioinformatics, it has many applications including sequence alignment, genome and transcriptome assembly, RNA-seq expression quantification, k-mer counting and error correction.

Large-scale sequence analysis often relies on cataloguing or counting consecutive k-mers in DNA/RNA sequences for indexing, querying and similarity searching. An efficient way of implementing such operations is through the use of hash based data structures, such as hash tables or Bloom filters. Therefore, improving the performance of hashing algorithms would have a great impact in a wide range of bioinformatics tools. Here, we present ntHash, a fast function for recursively computing hash values for consecutive k-mers.

2 Methods

We propose an algorithm to hash consecutive k-mers in a sequence, r of length l > k, using a recursive function, f, in which the hash value of the current k-mer H is derived from the hash value of the previous k-mer:

| (1) |

Such a recursive function, also called rolling hash function, offers huge improvements in performance when hashing consecutive k-mers. This has been previously described and investigated for n-gram hashing for string matching, text indexing and information retrieval (Cohen, 1997; Gonnet and Baezayates, 1990; Karp and Rabin, 1987; Lemire and Kaser, 2010). In this paper, we have customized the concept for hashing all k-mers of a DNA sequence, and implemented an adapted version of the cyclic polynomial hash function, ntHash, to compute normal or canonical hash values for k-mers in DNA sequences efficiently. In hashing by cyclic polynomial, ntHash uses barrel shifts instead of multiplications to make the process faster. To compute hash values for all k-mers of the sequence r of length l, we first hash the initial k-mer, k-mer0, as follows:

| (2) |

where rol is a cyclic binary left rotation, ⊕ is the bit-wise EXCLUSIVE OR (XOR) operator, and h(.) is a seed table, where the letters of the DNA alphabet, Σ = {A, C, G, T}, are assigned different random 64-bit integers. The hash values for all consequent k-mers, k-mer1, …, k-merl-k, are then computed recursively as follows:

| (3) |

We note that the time complexity of ntHash for sequence r is O(k + l) compared to O(kl) complexity of regular hash functions. In some bioinformatics applications, one might be interested in computing the hash value of forward and reverse-complement sequences of a k-mer.

To do so, we add in the seed table integers that correspond to the complement bases, such that table indices of base-complement base pairs are separated by a fixed offset. Using this table, we can easily compute the hash value for the reverse-complement (as well as the canonical form) of a sequence efficiently, without actually reverse-complementing the input sequence, as follows:

| (4) |

where ror is a cyclic binary right rotation, and d is the offset of complement base in the seed table h(.).

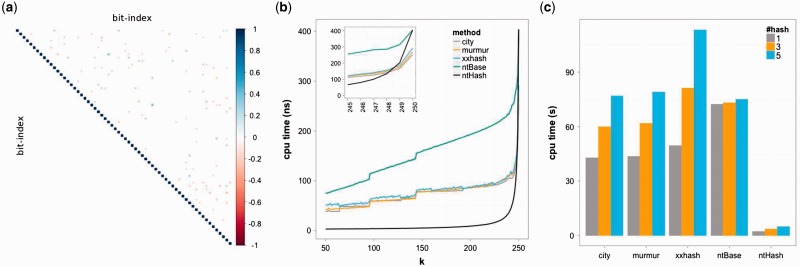

Further, ntHash provides a fast way to compute multiple hash values for a given k-mer, without repeating the whole procedure for each value. To do so, a single hash value is computed from a given k-mer, and then each extra hash value is computed by few more multiplication, shifting and XOR operations on the initial hash value (Supplementary Data). This would be very useful for certain bioinformatics applications, such as those that utilize the Bloom filter data structure. Experimental results demonstrate a substantial speed improvement over conventional approaches, while retaining a near-ideal hash value distribution (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables S1–S8).

Fig. 1.

Performance of ntHash. (a) A good hash function should have its values uniformly and independently distributed across the target domain. One way of measuring that is through correlation coefficients between the bits of hashed values. The plot shows natural statistical fluctuations for smaller sample sets (100 data points, the area above diagonal). The correlations dissipate rapidly for large sample sets (100 000 data points, the area below diagonal). (b) Runtime for hashing 250 bp DNA sequences with different k-mer lengths from 50 to 250. ntHash outperforms all other hash methods when hashing more than two subsequent k-mers, i.e. k < 249. (c) Comparing multi-hashing runtime of ntHash with the leading hash functions for one billion 50-mers. ntHash performs over 20× faster than the closest competitor, cityhash. Grey, orange and blue bars refer to calculation of one, three and five hash functions, respectively

In the Results section, we have used sequencing data on the human individual NA19238 from the Illumina Platinum Genomes project, as well as simulated random DNA sequences, as detailed in Supp. Data.

3 Results

A good hash function should generate hash values that are independently and uniformly distributed across the target domain, resulting in fewer collisions. To evaluate the independence of ntHash values, one way is to use the correlation coefficient between the bits of 64-bit hash values. That is, if each bit xi, i = 1..64, in a 64-bit hash value vector X = {x1, x2, …, x64} is an independent random variable, then there should be no correlation between them. To test this, we first generated sets of hash values for a given input. We next computed the (Pearson) correlation coefficient matrix for each sample set. Figure 1a shows the correlation coefficients of two sample sets of size 100 (above diagonal) and 100 000 (below diagonal). The plot shows natural statistical fluctuations for smaller sample sets. The correlations dissipate rapidly for large sample sets (Supplementary Figs S1–S5). Comparing the computed correlation coefficients with a confidence interval around the theoretical zero correlation shows that for all hash functions tested, the number of observations outside the 99.7% confidence is around 0.3%, in agreement with theoretical expectations.

We have also evaluated the uniformity of different hash methods by utilizing a Bloom filter data structure. Here, we first load a Bloom filter with a number of unique k-mers, and then query the Bloom filter with another set of unique k-mers. The results show the false positive rates of ntHash and other hash functions comply with the theoretical false positive rate for Bloom filters, indicating the uniform distribution of hash values generated by the tested hash methods (Supplementary Tables S1–S8).

We have compared the runtime performance of ntHash algorithm with three most widely used hash methods in bioinformatics: cityhash, murmur and xxhash (unpublished tools; references to websites provided in the Supplementary Materials). ntBase is the hash function for the base equation of ntHash (Eq. (2)). Figure 1b shows the runtimes for hashing different length k-mers in 5 000 000 DNA sequences of length 250 bp. In the inset, we see ntHash outperforms other algorithms when hashing more than two k-mers in a DNA sequence. Figure 1c illustrates a typical use case of computing multiple hash values for 50-mers in DNA sequences of length 250 bp, and shows that ntHash is over 20× faster than the closest competitor (Supplementary Figs S6, S7).

Funding

This work has been funded by BC Cancer Foundation, Genome BC, Genome Canada, UBC and NIH (under award number R01HG007182).

Conflict of Interest: The authors have a provisional patent on the technology with USPTO # 62288334.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cohen J.D. (1997) Recursive hashing functions for n-grams. ACM Trans. Inform. Syst., 15, 291–320. [Google Scholar]

- Gonnet G.H., Baezayates R.A. (1990) An analysis of the Karp-Rabin string matching algorithm. Inform. Process. Lett., 34, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Karp R.M., Rabin M.O. (1987) Efficient randomized pattern-matching algorithms. IBM J. Res. Dev., 31, 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lemire D., Kaser O. (2010) Recursive n-gram hashing is pairwise independent, at best. Comput. Speech Lang., 24, 698–710. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.