Abstract

Motivation: With the continued improvement of requisite mass spectrometers and UHPLC systems, Hydrogen/Deuterium eXchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) workflows are rapidly evolving towards the investigation of more challenging biological systems, including large protein complexes and membrane proteins. The analysis of such extensive systems results in very large HDX-MS datasets for which specific analysis tools are required to speed up data validation and interpretation.

Results: We introduce a web application and a new R-package named ‘MEMHDX’ to help users analyze, validate and visualize large HDX-MS datasets. MEMHDX is composed of two elements. A statistical tool aids in the validation of the results by applying a mixed-effects model for each peptide, in each experimental condition, and at each time point, taking into account the time dependency of the HDX reaction and number of independent replicates. Two adjusted P-values are generated per peptide, one for the ‘Change in dynamics’ and one for the ‘Magnitude of ΔD’, and are used to classify the data by means of a ‘Logit’ representation. A user-friendly interface developed with Shiny by RStudio facilitates the use of the package. This interactive tool allows the user to easily and rapidly validate, visualize and compare the relative deuterium incorporation on the amino acid sequence and 3D structure, providing both spatial and temporal information.

Availability and Implementation: MEMHDX is freely available as a web tool at the project home page http://memhdx.c3bi.pasteur.fr

Contact: marie-agnes.dillies@pasteur.fr or sebastien.brier@pasteur.fr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data is available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Hydrogen Deuterium eXchange followed by Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) is a biophysical tool in structural biology capable of probing protein/ligand interactions, conformational changes and protein folding and dynamics (Konermann et al., 2011; Tsutsui and Wintrode, 2007; Wales and Engen, 2006). Despite an increased number of applications (Jaswal, 2013; Pirrone et al., 2015), the expansion of the technology has been slowed by its intrinsic technical and analytical complexity (i.e. digestion at pH 2.5 and rapid HPLC separation at 0 °C). With recent advancements in sample preparation robotics, refrigerated ultra-high performance liquid chromatography systems (Venable et al., 2012; Wales et al., 2008) and high-resolution mass spectrometers, HDX-MS has surged in popularity and is now emerging from the academic benchtop to the expanse of the pharmaceutical sector (Campobasso and Huddler, 2015; Huang and Chen, 2014; Majumdar et al., 2015; Marciano et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2014).

The use of improved HDX-MS workflows enables the structural analysis of larger protein systems such as antigen-antibody complexes (> 180 kDa) or integral membrane proteins, in a more routine way (Bertoldi et al., 2016; Chung et al., 2011; Faleri et al., 2014; Malito et al., 2014; Malito et al., 2013). The characterization of such systems results in very complex HDX-MS datasets, for which specific non-commercial analytical software (e.g. HXExpress, HeXicon, ExMS, HDXFinder, etc.), as well as commercial platforms (e.g. DynamX and HDExaminer), have been developed (Guttman et al., 2013; Hamuro et al., 2003; Kan et al., 2011; Kreshuk et al., 2011; Lindner et al., 2014; Lou et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2012; Weis et al., 2006). Such software extract deuterium incorporation information from (un)processed raw m/z data files and produce deuterium uptake curves that can pinpoint regions of interest on protein 3D structures. However, many of these tools do not integrate statistical approaches and use the absolute difference of deuterium uptake to evaluate the significance between conditions.

Hydra (or Mass Spec Studio) was the first standalone application to introduce Student’s t-test and P-values to statistically evaluate the difference across HDX-MS experiments (Rey et al., 2014; Slysz et al., 2009). Alternatively, Houde et al. (2011) calculated confidence limits based on the experimental uncertainty of measuring deuterium uptake across replicates. In this context, two distinct confidence limits were calculated manually using either the differences of deuterium uptake or the summed value of HDX differences measured for each peptide, in each condition, and at each time point. Lastly, HDX Workbench includes a two-tailed t-test and Tukey multiple comparison procedure for the statistical cross-comparison of two or more datasets (Pascal et al., 2009; Pascal et al., 2007, 2012).

Despite significant efforts to design requisite statistical tools, the aforementioned software solutions are suitable to analyze HDX-MS data at one time point only, failing to account for the time dependency of the HDX-MS reaction. Thus, Liu et al. (2011) proposed a multiple regression or ANCOVA model. By deriving a statistical test based on the model parameters, they evaluated the significant difference between two groups under comparison, for all peptides in the dataset, and across all independent replicates.

Expanding on this, we introduce a web application named ‘MEMHDX’ (Mixed-Effects Model for HDX experiments) to aid in the rapid statistical validation and visualization of large HDX-MS datasets. MEMHDX uses a linear mixed-effects model where replicates are considered as random effects. This accounts for both the time dependency and the variability across replicates. Moreover, instead of testing the variation in global deuterium exchange between two experimental conditions, we propose to calculate two individual P-values for each peptide. First, the difference between conditions is measured (P-value for the ‘Magnitude of Delta Deuterium (ΔD)’), followed by the evolution of the deuterium uptake behavior over the time course of the experiment (P-value for the ‘Change in dynamics’). MEMHDX, therefore, allows the clustering of each peptide in the dataset based on these two respective P-values. A user-friendly interface developed with Shiny by RStudio facilitates the use of the application, allowing the user to easily visualize and compare the relative deuterium incorporation across the entire protein sequence and 3D structure. As a test system, we used the receptor-binding Repeat-in-ToXin (RTX) domain of CyaA produced by Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, to pinpoint regions undergoing structural and conformational changes upon calcium binding (O'Brien et al., 2015; Sotomayor-Perez et al., 2015).

2 Methods

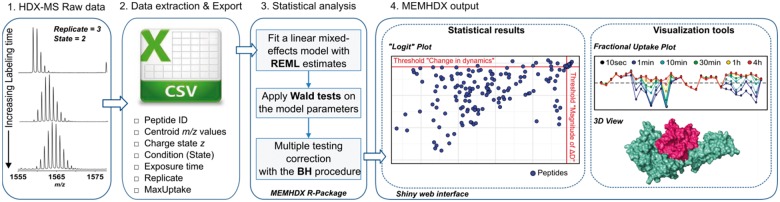

The description of the MEMHDX workflow is reported in Figure 1. MEMHDX is composed of two independent elements: a statistical tool written in R for the validation of HDX results and a web interface developed with Shiny. Details of the mixed-effects model, the Shiny web interface and the outputs are given below.

Fig. 1.

The MEMHDX strategy. (A) .csv file containing deuterium uptake values for all identified peptides is exported after raw data extraction and analysis by dedicated HDX-MS software (e.g. DynamX). The .csv file is uploaded to MEMHDX where a linear mixed-effects model is applied to statistically validate the dataset. Main results are displayed on a ‘Logit’ representation (for data clustering and validation) and visualized using a global summary plot and the 3D structure, where available. A user-friendly ShinyInterface facilitates the use of the application (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

2.1 The MEMHDX R-package

2.1.1 The mixed-effects model

The aim was to compare the exchange behavior of a defined set of N peptides derived from the same protein placed in two distinct states. The incorporation was measured at T time points (t1,…,tT) for all peptides in both biological conditions, and the experiment was repeated R times. Ya,i,r,t corresponds to the deuterium incorporation value measured for peptide a (), at each time point t (), for each replicate r () and condition (), and can be calculated using:

where M and M0 correspond to the mass of the labeled and the unlabeled peptide, c represents the extracted centroid value (m/z) and z the peptide charge. Thus, we consider the following linear mixed-effects model:

where is the vector of observations , βt, βi and βti correspond to the vectors of fixed effects for the time, the condition and the interaction between time and condition, ur the vector of random errors. In our model, the time t, the condition i, and the interaction between t and i are considered as fixed effects. The condition and the interaction represent the two parameters of interest. The replicates are considered as a random effect.

2.1.2 The statistical inference

The ‘nmle’ R package was utilized to estimate the vectors of fixed effects (β) and ur (http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme). The restricted maximum-likelihood method was used to fit the linear mixed-effects model. To evaluate the statistical significance of the condition and the interaction on the rate of deuterium incorporation of the protein, two P-values were calculated per peptide, using two individual Wald tests. The condition-associated P-value (hereafter referred to as P-valueMagnitude_of_Delta_D) tests the null hypothesis of there being no difference in deuterium uptake between conditions 1 and 2; the interaction-associated P-value (hereafter referred to as P-valueChange_in_dynamics) tests the null hypothesis of there being no change in the deuterium uptake behavior between conditions 1 and 2 and takes into account the time dependency of the HDX reaction (see Comment 1 of Supplementary material). A multiple testing procedure was applied to adjust the significance level of each Wald test. In this work, the false discovery rate (FDR) criterion was used instead of the classical familywise error rate to achieve higher statistical power (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

2.2 User interface and data output

2.2.1 The ‘start analysis’ window

To facilitate the use of the MEMHDX R-package, a user-friendly interactive web interface was developed with Shiny by RStudio (http://shiny.rstudio.com). The ‘Start analysis’ window (Supplementary Fig. S1A) contains a short reminder of the main variables required in the input .csv file, i.e. the sequence and the position of each peptide in the protein, charge state z, extracted centroid m/z values for each time point and replicate and in each condition, exposure time (min), number of replicates, and the maximum number of exchangeable amide hydrogens (MaxUptake) that could be theoretically replaced into the peptide. MaxUptake corresponds to the number of amino acid residues contained in the peptide, minus the number of proline residues and minus one for the N-terminus that back-exchanges too rapidly to be measured (Englander and Kallenbach, 1983). Once the .csv file is loaded, the system informs the user of any missing variables. Missing centroid m/z values are allowed; in such a scenario, they are automatically replaced by the mean value across all replicates.

Before starting any analysis, two user-defined parameters must be defined: the statistical significance value (%) corresponding to the desired stringency of the analysis and the percentage of deuterium (D) contained in the final labeling solution (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The latter is used to calculate the relative fractional uptake (RFU) values. MEMHDX automatically generates RFU values as follows:

where Ya,i,r,t corresponds to the deuterium incorporation value measured for peptide a at each time point t. RFU can be viewed as normalized deuterium uptake values (i.e. the number of incorporated deuterium becomes independent of the length of the peptide) and are utilized to generate the global visualization charts.

2.2.2 Data output

Once processing is complete, the ‘HDX-MS Results’ panel appears below the ‘Start analysis’ window. This is composed of six independent tabs, namely Raw Data, Peptide Plot, Logit Plot, Global Visualization, 3D Structure and Summary.

The ‘Raw Data’ tab lists all the variables included in the .csv file. The ‘Peptide Plot’ tab (Supplementary Fig. S1B1) allows the user to control the quality of the fitted model for each peptide and to evaluate the reproducibility across replicates. The ‘Logit Plot’ tab summarizes the main statistical results (Supplementary Fig. S1B2). This is divided into three sections. The ‘plot options’ section is used to adjust the options of the plot (size points, max distance in pixels) and the export. The center area displays the ‘Logit’ representation, where each dot represents one individual peptide. The Logit function of the two P-values defines the position of each peptide in the graph. The red lines correspond to the statistical significance threshold for the ‘Magnitude of ΔD’ (vertical line), and for the ‘Change in dynamics’ (horizontal line), thus dividing the ‘Logit’ plot into four regions (Supplementary Fig. S1B2): peptides only statistically significant for the ‘Change in dynamics’ or the ‘Magnitude of ΔD’ are located in the ‘a’ and the ‘b’ region, respectively; statistically significant peptides in both states are clustered in the ‘c’ region; statistically non-significant peptides are displayed in the ‘d’ region. The ‘Logit’ viewing mode of MEMHDX provides a rapid and effective way to discriminate statistically significant from non-significant peptides and to classify each based on their respective HDX behavior. The final section appears at the bottom of the ‘Logit’ screen after selection of an individual peptide in the ‘Logit’ representation (not shown). MEMHDX automatically displays a summary table containing the mean incorporation (in Da) per time point, and state, and associated ‘Logit’ values. This summary table can be exported into a .csv format. The identity of each peptide (i.e. sequence, position and deuterium uptake curves) appears below the ‘Logit’ plot when the mouse cursor is hovered over a dot.

The ‘Global Visualization’ and the ‘3D Structure’ tabs are dedicated to the visualization of the HDX data and contain two sections (Supplementary Figs S1B3 and 1B4). The left section allows the user to navigate through the different parameter options. The right section of the ‘Global Visualization’ summarizes the deuterium uptake behavior observed in the two states (Supplementary Fig. S1B3, upper and middle charts). The RFU values calculated by MEMHDX are plotted as a function of peptide position. In addition, the lower chart plots the difference in RFU between states 1 and 2, providing a more quantitative assessment of the difference between states. Statistically significant peptides are highlighted in gray. The right section of the ‘3D Structure’ tab displays the mapping of the HDX results on the crystal structure of the protein (Supplementary Fig. S1B4). Finally, the ‘Summary’ tab recaps the different parameters used by MEMHDX to perform the statistical analysis and includes an export option for both the raw data and statistically relevant results (not shown).

3 Results and discussion

MEMHDX was developed to complement the HDX-MS pipeline commercialized by Waters Corporation. The software is fully compatible with the main output generated by DynamX (i.e. cluster data), but has been designed to handle data from any HDX-MS platform, as long as the input file is structured in .csv format and with the appropriate architecture, i.e., columns listed in Panel 1 of Supplementary Figure S1A.

MEMHDX was evaluated using our recently published differential HDX-MS dataset generated with the C-terminal Repeat-in-toxin Domain (RD, 701 residues) of the CyaA toxin (O'Brien et al., 2015). Briefly, we used HDX to identify and locate secondary structural elements in the intrinsically disordered Apo-RD protein, and followed its transition to a more compact and folded state upon calcium binding. In total, 13 experimental time points were selected, and all data was collected in triplicate.

3.1 Pre-processing and dataset quality control

A total of 602 peptic peptides of RD were identified by ProteinLynX Global Server (Waters Corporation) using the default search parameters, of which 198 remained after filtering by DynamX. Following this, 162 were selected for HDX analysis and covered 98.4% of the RD sequence (Supplementary Fig. S2). Considering 162 peptides, 1 charge state, 3 replicates, 14 time points (including the unlabeled control) and 2 conditions, we have up to 13 608 unique data points in the complete test dataset. This demonstrates the complexity of datasets acquired using modern HDX-MS pipelines, the processing and interpretation of which is extremely challenging and time consuming by traditional, manual means.

The current version of MEMHDX can only handle one unique charge state per peptide. A pre-processing step is required by the user to select the most appropriate charge state for analysis. The quality determination of the dataset is directly accomplished by MEMHDX. A Box and Whisker plot displaying the agreement across replicates is automatically generated (Supplementary Fig. S1B1). For each peptide, the calculated deuterium uptake values (Ya,i,r,t) are averaged across all time points in each respective state. This comparison is possible as each replicate is considered as an independent variable. A scoring function (log-likelihood) is determined per peptide to easily control the quality of the fitting. MEMHDX includes a filtering option to sort each peptide according to this score and to remove those with a low fitting quality from the analysis.

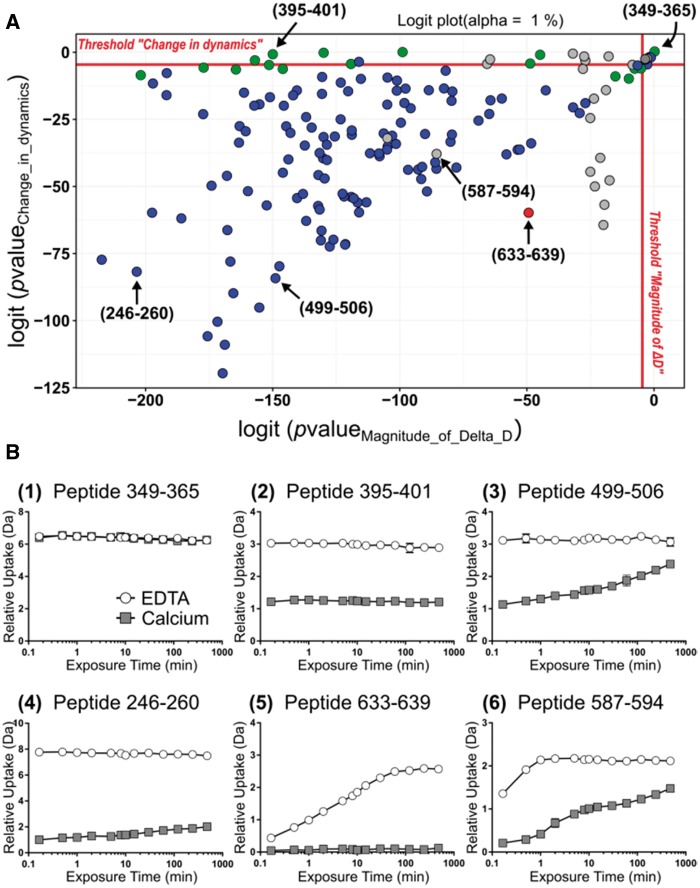

3.2 Statistical analysis and peptide clustering

A central feature of MEMHDX lies in its ability to classify peptides based on their respective HDX behaviors. MEMHDX automatically summarizes and displays the statistical results by means of a ‘Logit’ representation. Two adjusted P-values are calculated by the software and define the position of each peptide in the ‘Logit’ plot (Fig. 2A). On one hand, the magnitude of ΔD-associated P-value defines the magnitude of difference of deuterium uptake between the two states investigated, while on the other hand, the change in dynamics-associated P-value describes the timewise evolution of HDX behavior between states. Considering the magnitude of ΔD only, the significance increases (i.e. P-value decreases) as the peptide position moves from right to left on the plot, due to the greater magnitude of change observed between states. Similarly, the significance of change in dynamics increases as the peptide position moves from top to bottom. Deuterium uptake curves for selected peptides are displayed in Figure 2B to illustrate the clustering performed by the software. Statistically non-significant peptides are clustered in the top right-hand corner (e.g. peptides 349–365). Statistically significant peptides for the magnitude of ΔD only are found at the top of the plot (e.g. peptides 395–401), whereas those significant for the change in dynamics only are plotted on the far right (not applicable to this dataset). Those peptides which are significant for both states are located in the center of the plot. Comparing peptides 395–401, 499–506 and 246–260 allows us to easily visualize the effect of a change in the magnitude of ΔD- or the change in dynamics-associated P-value. Peptides 395–401 and 499–506 possess the same magnitude of ΔD-associated P-value, but are separated by their differing change in dynamics-associated P-value. This difference is directly linked to the change of HDX behavior observed in peptides 499–506 in the presence of calcium, which is not observed in the other peptide (Fig. 2B). Conversely, peptides 499–506 and 246–260 differ only by their magnitude of ΔD-associated P-value because the magnitude of difference between states is less for the former than the latter.

Fig. 2.

Example of statistical results generated with MEMHDX. (A) ‘Logit’ plot obtained with RD. The effect of calcium binding on the deuterium uptake behavior was measured on 162 RD peptides. Each dot corresponds to one unique peptide. Peptides are classified and color-coded based on their respective HDX behavior: peptides showing dynamic events in both the Apo- and Holo-state are colored in gray; peptides only dynamic in the Apo- or Holo-state are colored in red and blue; non-dynamic peptides in both states are colored in green. The statistical significance threshold was set to 1%. (B) Deuterium uptake curves for selected peptides in the Apo- (open circles) and Holo- (filled squares) states. The position of each in the ‘Logit’ plot is also reported (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

MEMHDX enables the user to color code all peptides in each state based on their respective HDX behavior (Fig. 2A). Dynamic peptides in two states are colored in gray (e.g. peptide 587–594), whereas those which are dynamic in one or the other state are colored in red or blue [Apo-RD (e.g. peptides 633–639) in red, and Holo-RD (e.g. peptides 499–506) in blue herein]. Non-dynamic peptides are colored in green (e.g. peptide 395–401). Results generated with MEMHDX were compared with those manually obtained for RD (O'Brien et al., 2015). Excellent agreement was observed between the automated software and the manual approach. However, the speed of analysis was greatly increased by MEMHDX and the validation completed in one full day (10–15 s to generate the statistical results by the software, followed by several hours of user interpretation), compared with up to 2 weeks by manual analysis. Visually speaking, the difference in deuterium uptake between the two states was too small to be considered as significant in the manual analysis of some peptides. With the introduction of two independent P-values, the sensitivity of MEMHDX over the manual approach is enhanced. This is apparent for RD region 1–25, where segment 16–25 was considered as non-significant in the manual analysis, whereas was found to be statistically relevant by MEMHDX (Fig. 3A and B). This illustrates the advantages of our automated MEMHDX approach over manual means.

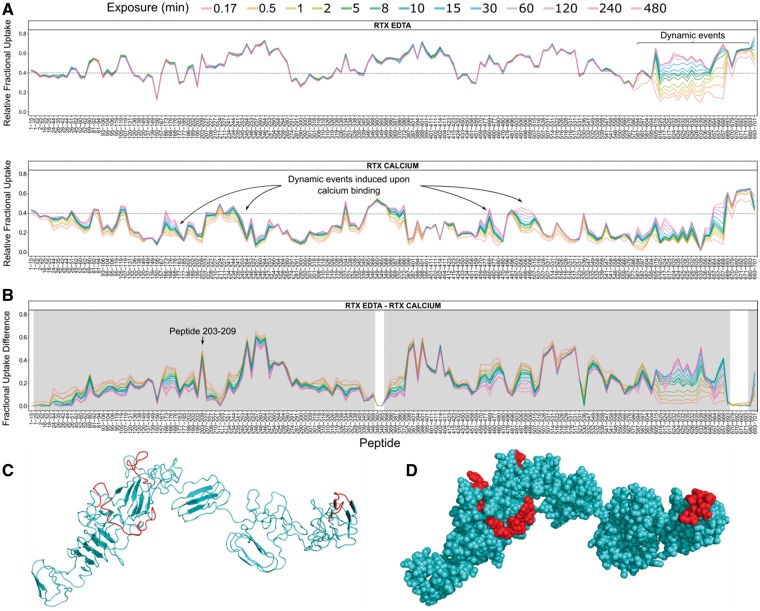

Fig. 3.

HDX-MS results visualized by MEMHDX. (A) Global visualization plots of RD in both the Apo- and Holo-state. The relative fractional uptake values are plotted as a function of peptide position. This representation allows the user to visualize the deuterium uptake behavior of each peptide across the entire protein sequence. (B) Fractional uptake difference plot showing the variations of deuterium uptake between Apo- and Holo-RD. A high-uptake difference value corresponds to a large calcium-induced protective effect, while a low value is indicative of a weak effect. Significant peptides are highlighted in gray. The statistical significance threshold was set to 1%. (C and D) Mapping of the HDX results on the model of RD using the 3D-structural tool of MEMHDX. RD is shown as a cartoon or in a space filling model. Regions experiencing deuterium uptake or dynamic changes upon calcium binding are colored in cyan; regions with no change are colored in red (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

3.3 Global and 3D visualization

MEMHDX integrates two visualization tools to facilitate the interpretation of the HDX results. The ‘global visualization’ tool contains two distinct plots. The relative fractional uptake plot enables the user to directly visualize and compare the relative deuterium uptake and the exchange behavior of each peptide across the entire protein sequence, providing both spatial and temporal information (Fig. 3A). Using this representation, the regions of the RD-protein containing residual structural elements in the Apo-state or acquiring secondary structures in the Holo-state are easily identified. The second plot displays the difference in relative fractional uptake between the two states (Fig. 3B). A high uptake difference indicates that the peptide incorporates more deuterium in state 1 than in state 2 and vice versa. This is the case for peptides 203–209 of RD, which incorporates more deuterium in the Apo-state than in the Holo-state, indicative of a calcium-induced protective effect (Fig. 3B). In addition, the statistical results are reported on the differential uptake plot. Statistically non-significant peptides are highlighted in white, whereas those displaying significant P-values in gray.

The second visualization tool allows the mapping of the HDX results on the 3D structure of the protein (Fig. 3C and D). The user can either download a PDB file or enter the

Protein DataBank identifier of the protein. In this scenario, MEMHDX will automatically retrieve and display the structure from the protein databank archive. Differential exchange behaviors will be color-coded to distinguish modified from unmodified regions (Fig. 3C and D).

4 Conclusions

MEMHDX is a statistical tool designed to aid in the analysis of large HDX-MS datasets. The initial concept of the software was to complement the HDX-MS solution provided by Waters Corporation, which is to-date, the only complete automated pipeline commercially available. The use of two distinct P-values in the handling of HDX-MS data introduces a novel way to interpret and classify HDX results. This was successfully demonstrated here with the analysis of the RD protein from the adenylate cyclase toxin. In this regard, the validation of the complete RD dataset was significantly expedited, taking only 1 day with MEMHDX, compared with up to 2 weeks when performed manually. The current version of the software allows for the comparison of two unique conditions using only one unique charge state. As a future perspective, the software will be enhanced to allow for the comparison of multiple conditions, using multiple charge states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christophe Malabat for providing the virtual machine, Amine Ghozlane for his help with the 3D visualization tool and Diogo Borges Lima for his contribution to the on-line tutorial.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur (Projet Transversal de Recherche, PTR#451 and PasteurInnov TransCyaA 2015), the Centre national de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS UMR 3528, Biologie Structurale des Processus Cellulaires et Maladies Infectieuses; CNRS USR 3756) and funding from the Investissements d’Avenir through the CACSICE project.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: s practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.), 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoldi I. et al. (2016) Exploiting chimeric human antibodies to characterize a protective epitope of Neisseria adhesin A, one of the Bexsero vaccine components. FASEB J., 30, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campobasso N., Huddler D. (2015) Hydrogen deuterium mass spectrometry in drug discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 25, 3771–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K.Y. et al. (2011) Conformational changes in the G protein Gs induced by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. Nature, 477, 611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander S.W., Kallenbach N.R. (1983) Hydrogen exchange and structural dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids. Q. Rev. Biophys., 16, 521–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faleri A. et al. (2014) Two cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies recognize overlapping epitopes on Neisseria meningitidis factor H binding protein but have different functional properties. FASEB J., 28, 1644–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M. et al. (2013) Analysis of overlapped and noisy hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 24, 1906–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamuro Y. et al. (2003) Rapid analysis of protein structure and dynamics by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J. Biomol. Tech.: JBT, 14, 171–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde D. et al. (2011) The utility of hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry in biopharmaceutical comparability studies. J. Pharm. Sci., 100, 2071–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R.Y.C., Chen G.D. (2014) Higher order structure characterization of protein therapeutics by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 406, 6541–6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal S.S. (2013) Biological insights from hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Bba – Proteins Proteom., 1834, 1188–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Z.Y. et al. (2011) ExMS: data analysis for HX-MS experiments. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 22, 1906–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann L. et al. (2011) Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry for studying protein structure and dynamics. Chem. Soc. Rev., 40, 1224–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreshuk A. et al. (2011) Automated detection and analysis of bimodal isotope peak distributions in H/D exchange mass spectrometry using HeXicon. Int. J. Mass Spectrom., 302, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner R. et al. (2014) Hexicon 2: automated processing of hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry data with improved deuteration distribution estimation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 25, 1018–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. et al. (2011) HDX-analyzer: a novel package for statistical analysis of protein structure dynamics. BMC Bioinformatics, 12, S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X. et al. (2010) Deuteration distribution estimation with improved sequence coverage for HX/MS experiments. Bioinformatics, 26, 1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar R. et al. (2015) Hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry as an emerging analytical tool for stabilization and formulation development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. J. Pharm. Sci., 104, 327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malito E. et al. (2014) Structure of the meningococcal vaccine antigen NadA and epitope mapping of a bactericidal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 111, 17128–17133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malito E. et al. (2013) Defining a protective epitope on factor H binding protein, a key meningococcal virulence factor and vaccine antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 110, 3304–3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciano D.P. et al. (2014) HDX-MS guided drug discovery: small molecules and biopharmaceuticals. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 28, 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D.E. et al. (2012) HDXFinder: automated analysis and data reporting of deuterium/hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 23, 425–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien D.P. et al. (2015) Structural models of intrinsically disordered and calcium-bound folded states of a protein adapted for secretion. Sci. Rep., 5, 14223.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal B.D. et al. (2007) The Deuterator: software for the determination of backbone amide deuterium levels from H/D exchange MS data. BMC Bioinformatics, 8, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal B.D. et al. (2009) HD desktop: an integrated platform for the analysis and visualization of H/D exchange data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 20, 601–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal B.D. et al. (2012) HDX workbench: software for the analysis of H/D exchange MS data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 23, 1512–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone G.F. et al. (2015) Applications of hydrogen/deuterium exchange MS from 2012 to 2014. Anal. Chem., 87, 99–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey M. et al. (2014) Mass spec studio for integrative structural biology. Structure, 22, 1538–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slysz G.W. et al. (2009) Hydra: software for tailored processing of H/D exchange data from MS or tandem MS analyses. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor-Perez A.C. et al. (2015) Disorder-to-order transition in the CyaA toxin RTX domain: implications for toxin secretion. Toxins, 7, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui Y., Wintrode P.L. (2007) Hydrogen/deuterium, exchange-mass spectrometry: a powerful tool for probing protein structure, dynamics and interactions. Curr. Med. Chem., 14, 2344–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venable J.D. et al. (2012) Subzero temperature chromatography for reduced back-exchange and improved dynamic range in amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem., 84, 9601–9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales T.E., Engen J.R. (2006) Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry for the analysis of protein dynamics. Mass Spectrom. Rev., 25, 158–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales T.E. et al. (2008) High-speed and high-resolution UPLC separation at zero degrees Celsius. Anal. Chem., 80, 6815–6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H. et al. (2014) Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry for probing higher order structure of protein therapeutics: methodology and applications. Drug Discov. Today, 19, 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis D.D. et al. (2006) Semi-automated data processing of hydrogen exchange mass spectra using HX-Express. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 17, 1700–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.