Abstract

Summary: The MSAViewer is a quick and easy visualization and analysis JavaScript component for Multiple Sequence Alignment data of any size. Core features include interactive navigation through the alignment, application of popular color schemes, sorting, selecting and filtering. The MSAViewer is ‘web ready’: written entirely in JavaScript, compatible with modern web browsers and does not require any specialized software. The MSAViewer is part of the BioJS collection of components.

Availability and Implementation: The MSAViewer is released as open source software under the Boost Software License 1.0. Documentation, source code and the viewer are available at http://msa.biojs.net/.

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

Contact: msa@bio.sh

1 Introduction

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) is a fundamental procedure to capture similarities between sequences of nucleotides (DNA/RNA) or of amino acids (protein). Biologically meaningful MSAs highlight and capture sites with significant evolutionary conservation. MSAs are essential to predict aspects of protein structure (e.g. secondary structure (Rost, 2001) or protein disorder (Schlessinger et al., 2011)) and function [e.g. binding sites (Ofran et al., 2007) or localization (Goldberg et al., 2014)]. MSAs can be used to understand genomic rearrangements (Darling et al., 2004), to derive sequence homology (Altschul et al., 1990) and to identify evolutionary rates (Pupko et al., 2002).

MSAs are widely used to display complex annotations relating to structure and function, and to transfer those annotations to sequences that lack annotations (Waterhouse et al., 2009). Many tools are available to view and analyze MSAs, including standalone applications (Larsson, 2014; Waterhouse et al., 2009) and web applets (Waterhouse et al., 2009). With the recent widespread adoption of JavaScript as the leading programming language for interactive web applications, new MSA viewing tools compatible with modern web browsers have been developed and made available (Martin, 2014). BioJS is one particular collection of JavaScript components with growing applications in biology (Corpas et al., 2014); it is interoperable with many other data visualization tools.

Here, we describe the BioJS MSAViewer. It is readily loaded into web pages to visualize and analyze MSA datasets of arbitrary sizes. MSAViewer implements most features commonly available in other popular MSA viewing software, including scrolling, selecting, highlighting, cross-referencing with protein feature annotations and phylogenetic trees (a detailed comparison of features is in Supplementary Table S1).

2 Visualization

The MSAViewer loads MSA data in FASTA (Pearson, 2000) or CLUSTAL (Larkin et al., 2007) formats from a user’s local computer or a web server. It then draws two main Canvas panels—the main panel and the overview MSA panel (Fig. 1). The choice to use Canvas over other rendering technologies is discussed in Supplementary Material Section S1.

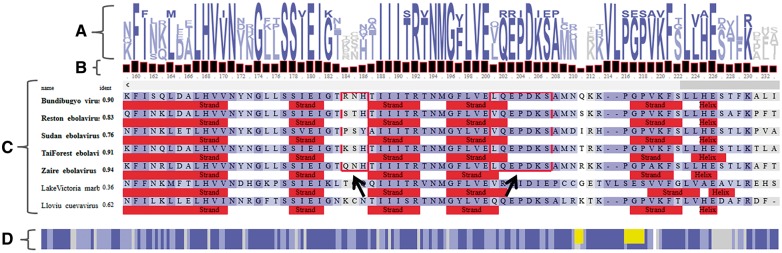

Fig. 1.

A simplified view of the MSAViewer for the sequence alignment of protein VP24 within seven viruses of Filoviridae family. (A) Sequence logo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990) representation with conservation patterns at each position in the MSA. (B) Bar chart showing amino acid conservation per position. (C) Main MSA panel with residues in the alignment colored according to the Percentage Identity coloring scheme (Waterhouse et al., 2009). Percentage sequence identities relative to consensus (consensus sequence not shown) are listed for each sequence. Filled red rectangles indicate sequence annotations provided by the user [here: secondary structure predictions of PredictProtein (Yachdav et al., 2014)]. Red frames (indicated by two black arrows) are clusters of residues of ebolavirus VP24 responsible for binding to karyopherin alpha nuclear transporters to suppress antiviral defense mechanism in human (Xu et al., 2014). (D) A compact overview MSA showing a bird’s eye view of the full alignment. Yellow rectangles are two highlighted clusters in the main MSA panel. Despite the overall sequence homology, the highlighted regions in ebolavirus (EBOV) proteins binding karyoprotein differ from those in Llovu cuevavirus (LLOV) and Lake Victoria marburgvirus (MARV). MARV is known to not suppress host’s antiviral defense mechanism (Xu et al., 2014). Though no experimental information on binding of LLOV VP24 to karyoproteins is available to date, the comparison of its sequence and structural features suggests a mechanism that is more similar to EBOV than to MARV

Navigation through the alignment is enabled through various controls. First, users can scroll or use the ‘jump to a column’ menu item to navigate to a certain column number. Second, users can pan within the main panel to scroll through the alignment; this has proven to be a useful feature for large alignments. Finally, a second panel—the overview panel (drawn under the main panel)—provides a ‘bird’s eye view’ perspective over the entire alignment and can also be used for navigation.

The alignment is sortable by unique identifiers, sequence labels and sequences. The percentage of gaps and the sequence identity to the consensus sequence, which is calculated from most frequent bases at each position in the alignment, can also be used for sorting. Users can select sequences, columns, or arbitrary regions for analysis, and hide them from the main panel based on their selection, conservation to the consensus sequence or the percentage of gaps. An alignment can also be searched for motifs using a regular expression (e.g. K(K|R)RK for a nuclear localization signal), which are highlighted with a red frame if matched. Sequence position annotations, such as binding sites, are provided by a user and displayed as filled rectangles below the corresponding sequence in the alignment. Users can switch between 15 predefined color schemes. The MSAViewer exports alignments and annotations as ASCII files, and the visual representation as a publication-quality figure.

3 Summary

MSAViewer is a lightweight viewer for MSAs of arbitrary size. Being JavaScript-based, it can be used on any modern web browser without installing any specialized software or add-ons. As part of BioJS, the MSAviewer can interoperate with a growing set of biological data viewers. The phylogenetic tree and the sequence logo viewers are already integrated in the current release. Integration with new MSA visualization techniques, e.g. sequence bundles (Kultys et al., 2014) is planned. The MSAViewer has already been found useful and became part of Galaxy (Giardine et al., 2005) https://cpt.tamu.edu/clustalw-msa-and-visualisations and JalView (Waterhouse et al., 2009) http://www.jalview.org/help/html/features/biojsmsa.html.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich Studienwerk and the Google Summer of Code program sponsored by Google Inc.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Altschul S.F. et al. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas M. et al. (2014) BioJS: an open source standard for biological visualisation - its status in 2014. F1000Res., 3, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling A.C. et al. (2004) Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res., 14, 1394–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B. et al. (2005) Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res., 15, 1451–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg T. et al. (2014) LocTree3 prediction of localization. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, W350–W355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultys M. et al. (2014) Sequence Bundles: a novel method for visualising, discovering and exploring sequence motifs. BMC Proc., 8, S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M.A. et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics, 23, 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A. (2014) AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics, 30, 3276–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A.C. (2014) Viewing multiple sequence alignments with the JavaScript Sequence Alignment Viewer (JSAV). F1000Res., 3, 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofran Y. et al. (2007) Prediction of DNA-binding residues from sequence. Bioinformatics, 23, i347–i353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W.R. (2000) Flexible sequence similarity searching with the FASTA3 program package. Methods Mol. Biol, 132, 185–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupko T. et al. (2002) Rate4Site: an algorithmic tool for the identification of functional regions in proteins by surface mapping of evolutionary determinants within their homologues. Bioinformatics, 18, S71–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B. (2001) Review: protein secondary structure prediction continues to rise. J. Struct. Biol., 134, 204–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger A. et al. (2011) Protein disorder–a breakthrough invention of evolution? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 21, 412–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T.D., Stephens R.M. (1990) Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 6097–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.M. et al. (2009) Jalview Version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics, 25, 1189–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. et al. (2014) Ebola virus VP24 targets a unique NLS binding site on karyopherin alpha 5 to selectively compete with nuclear import of phosphorylated STAT1. Cell Host Microbe, 16, 187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachdav G. et al. (2014) PredictProtein–an open resource for online prediction of protein structural and functional features. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, W337–W343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.