Abstract

Summary: Measuring motif similarity is essential for identifying functionally related transcription factors (TFs) and RNA-binding proteins, and for annotating de novo motifs. Here, we describe Motif Similarity Based on Affinity of Targets (MoSBAT), an approach for measuring the similarity of motifs by computing their affinity profiles across a large number of random sequences. We show that MoSBAT successfully associates de novo ChIP-seq motifs with their respective TFs, accurately identifies motifs that are obtained from the same TF in different in vitro assays, and quantitatively reflects the similarity of in vitro binding preferences for pairs of TFs.

Availability and implementation: MoSBAT is available as a webserver at mosbat.ccbr.utoronto.ca, and for download at github.com/csglab/MoSBAT.

Contact: t.hughes@utoronto.ca or hamed.najafabadi@mcgill.ca

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The sequence preference of a transcription factor (TF) or an RNA-binding protein (RBP) is most commonly represented using a ‘motif’, which refers to the matrix of the probabilities of occurrence of any given nucleotide at any given position of the binding site. Measuring the similarity of motifs is fundamental to several aspects of studying TFs and RBPs, such as elucidating the relationship between sequence and function of these factors (Weirauch et al., 2014), assigning known TFs and RBPs to de novo discovered motifs (Gupta et al., 2007), and measuring performance of in silico motif prediction approaches (Najafabadi et al., 2015).

The majority of motif comparison approaches are based on alignment of two motifs, where the similarity measure is defined as the score of the best alignment (Gupta et al., 2007; Mahony and Benos, 2007; Jiang and Singh, 2014). A few other methods use binding site predictions to identify overlapping sites in random sequences, allowing derivation of a motif similarity score and alignment (Pape et al., 2008). Here, we introduce an alignment-independent approach for measuring the similarity of two motifs. The method is based on measuring the similarity of the affinity profiles of TFs or RBPs across a large number of random sequences, with the affinity profiles predicted using the associated motifs. We show that our approach for measuring Motif Similarity Based on Affinity of Targets (MoSBAT) can accurately identify similar motifs that are derived from different experimental methods, e.g. in order to identify TFs associated with de novo motifs derived from ChIP-seq data. Motif similarity scores reported by MoSBAT also closely reflect independent sequence preference similarity measures derived directly from in vitro measurements.

2 Materials and methods

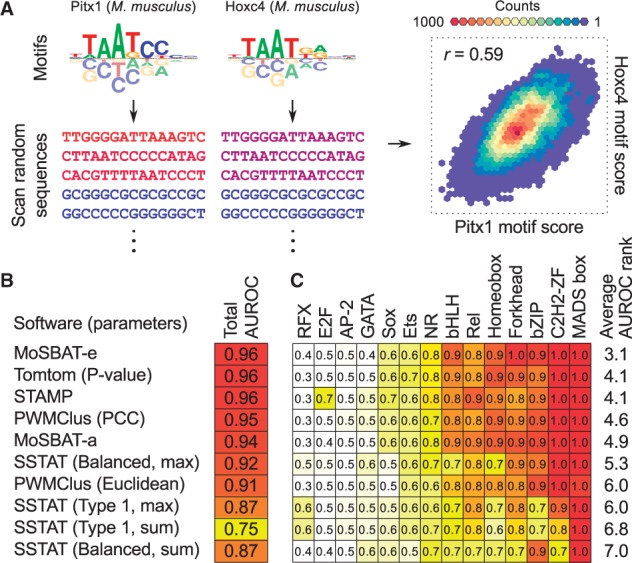

To measure the similarity of two motifs, we first convert the motifs to position-specific affinity matrices (PSAMs) (Foat et al., 2006). Then, we generate a set of N random sequences (N > 20 000) of length L (default 100 nt). For each of the two PSAMs, we calculate the score profile across the random sequences using PSAM scanning, as described in Supplementary Note S1. The resulting two vectors represent the binding ‘affinity’ profile of each of the motifs for the N sequences (Figure 1A). By taking the logarithm of affinity vectors, we obtain vectors that represent the binding ‘energy’ profiles of the motifs for the N sequences. Similarity of the two motifs is then calculated as the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of the two affinity vectors (MoSBAT-a), or the two energy vectors (MoSBAT-e). Additional details of the methods can be found in Supplementary Notes S1 and S2.

Fig. 1.

MoSBAT workflow and benchmarking results. (A) Schematic illustration of MoSBAT workflow. The sequence shades represent PSAM scores of sequences for each of the motifs, calculated as the sum of scanning scores for each sequence. (B) Benchmarking results for comparison of ChIP-seq versus in vitro motifs. The set of parameters used to run each method is indicated in parentheses; see original publications for explanation of the parameters. AUROC: area under ROC curve (C) AUROC values for ChIP versus in vitro comparison per TF structural class (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

MoSBAT is available as a webserver at http://mosbat.ccbr.utoronto.ca, and for download at https://github.com/csglab/MoSBAT. The input and output of the MoSBAT webserver are described in Supplementary Figure S1.

3 Benchmarking

We compared MoSBAT to four popular motif comparison tools (Gupta et al., 2007; Jiang and Singh, 2014; Mahony and Benos, 2007; Pape et al., 2008) by scoring their ability to correctly match the motifs obtained for the same protein from different assays. One such task is assigning the correct TFs to motifs discovered by ChIP-seq, based only on comparison to in vitro motifs. We compiled a set of 94 TFs with motifs that were discovered both by ChIP-seq and in vitro assays (PBM, SELEX, and B1H) in the CIS-BP database (Weirauch et al., 2014), and asked whether we can correctly label the ChIP-seq with their respective TFs by comparison to the available in vitro motifs. In this ‘classification’ task, the ‘positives’ are pairs of ChIP-seq and in vitro motifs that are obtained from the same TF, the ‘negatives’ are pairs of motifs that are obtained from different TFs, and the ‘predicted value’ is the similarity between the ChIP-seq motif and the in vitro motif, measured using different motif comparison tools. Among 11 variations of the five tools tested, MoSBAT-e, Tomtom (P-value) (Gupta et al., 2007) and STAMP (Mahony and Benos, 2007) were the best-performing methods with area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) of 0.96 (Figure 1B). Furthermore, when the performance of different motif comparison tools was measured in each TF structural class separately (Figure 1C), MoSBAT-e overall outperformed all other measures (average rank 3.1 across 14 structural classes), followed by Tomtom and STAMP (average rank 4.1). Similar results are obtained when comparing different motifs of the same protein derived from different in vitro assays (Supplementary Figure S2), suggesting that MoSBAT can correctly match related motifs across various experimental platforms.

We also found that, for motifs obtained from pairs of different TFs, MoSBAT scores closely correlate with similarity of the in vitro binding preferences of TFs obtained directly from high-dimensional PBM data (PCC of 8-mer Z-scores, Supplementary Figures S3–4). These results suggest that MoSBAT can quantitatively measure the underlying similarity of TF sequence specificity even after the high-dimensional PBM data have been summarized as motifs. In this regard, MoSBAT outperformed all other motif comparison tools by a large margin, and was more tolerant to experimental noise (Supplementary Figure S4).

We note that MoSBAT uses randomly generated sequences to calculate binding affinity profiles for measuring similarity of motifs. This stochastic process can potentially generate different scores every time for the same pair of motifs (Supplementary Note S3). However, our analyses suggest that MoSBAT-e scores are highly stable when >50 000 sequences are used for constructing the binding affinity profiles (Supplementary Figure S5). MoSBAT-a scores are also stable for short motifs, but have larger variance for some longer motifs (Supplementary Figure S5 and Supplementary Note S3). Indeed, when the results of our motif comparison between different in vitro methods are stratified by motif length, a small decrease in accuracy is observed for longer motifs especially when comparing PBM motifs to SELEX motifs, but this decrease in accuracy is comparable to that of Tomtom (Supplementary Figure S2D). Overall, given the superior performance of MoSBAT-e in almost all tests, and the biochemically relevant definition of its scoring measure, we present it as an easy to use tool for motif comparison.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by funds from McGill Faculty of Medicine to H.S.N.; grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [MOP-77721 and MOP-111007] and funding from Canadian Institute for Advanced Research to T.R.H.; and Doctoral Scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to S.A.L.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Foat B.C. et al. (2006) Statistical mechanical modeling of genome-wide transcription factor occupancy data by MatrixREDUCE. Bioinformatics, 22, e141–e149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. et al. (2007) Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol., 8, R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P., Singh M. (2014) CCAT: Combinatorial Code Analysis Tool for transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res., 42, 2833–2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony S., Benos P.V. (2007) STAMP: a web tool for exploring DNA-binding motif similarities. Nucleic Acids Res., 35, W253–W258. (Web Server issue): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafabadi H.S. et al. (2015) C2H2 zinc finger proteins greatly expand the human regulatory lexicon. Nat. Biotechnol., 33, 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape U.J. et al. (2008) Natural similarity measures between position frequency matrices with an application to clustering. Bioinformatics, 24, 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirauch M.T. et al. (2014) Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell, 158, 1431–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.