Abstract

Background:

Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is a multisystem disorder characterized by asthma, prominent peripheral blood eosinophilia, and vasculitis signs.

Case summary:

Here we report a case of CSS presenting with acute myocarditis and heart failure and review the literature on CSS with cardiac involvement. A 59-year-old man with general fatigue, numbness of limbs, and a 2-year history of asthma was admitted to the department of orthopedics. Eosinophilia, history of asthma, lung infiltrates, peripheral neurological damage, and myocarditis suggested the diagnosis of CSS. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a dilated hypokinetic left ventricle (left ventricular ejection fraction ∼40%) with mild segmental abnormalities in the septal and apical segments.

Conclusion:

By reviewing the present case reports, we concluded that (1) the younger age of CSS, the greater occurrence rate of complicating myocarditis and the poorer prognosis; (2) female CSS patients are older than male patients; (3) patients with cardiac involvement usually have a history of severe asthma; (4) markedly increased eosinophil count suggests a potential diagnosis of CSS (when the count increases to 20% of white blood cell counts or 8.1 × 109/L, eosinophils start to infiltrate into myocardium); and (5) negative ANCA status is associated with heart disease in CSS.

Keywords: Churg–Strauss syndrome, heart failure, myocarditis

1. Introduction

Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) is an eosinophil-rich necrotizing vasculitis of small-to-medium blood vessels that affects many organs including cardiac, pulmonary, renal, nervous, and vascular systems.[1] Symptomatic cardiovascular involvement occurs in as much as 27% to 47% of CSS cases and can present with eosinophilic vasculitis, pericarditis, pericardial effusion, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and acute heart failure.[2–4] Although uncommon, cardiac involvement is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this disorder.

Here we report a case of CSS presenting with acute myocarditis and heart failure and review the literature on CSS with cardiac involvement.

2. Case report

A 59-year-old man with general fatigue, numbness of limbs and a 2-year history of asthma was admitted to the department of orthopedics in our hospital. Two days later, he was short of breath and unable to lie flat in bed. Inhaled corticosteroids were ineffective. Levels of troponin, myocardial enzyme, and B-type natriuretic peptide were elevated, and coronary heart disease with acute heart failure was suspected. The patient was transferred to the cardiology intensive care unit for further diagnosis and treatment.

On admission to the unit, the patient had severe dyspnea and moderate edema of lower limbs, with body temperature 37.2°C, pulse 115 beats/min, and blood pressure 94/60 mm Hg. Auscultation of the chest showed diffused wheezing without crackles and cardiac examination revealed a muffled heart sound without murmur, rubs, or gallop.

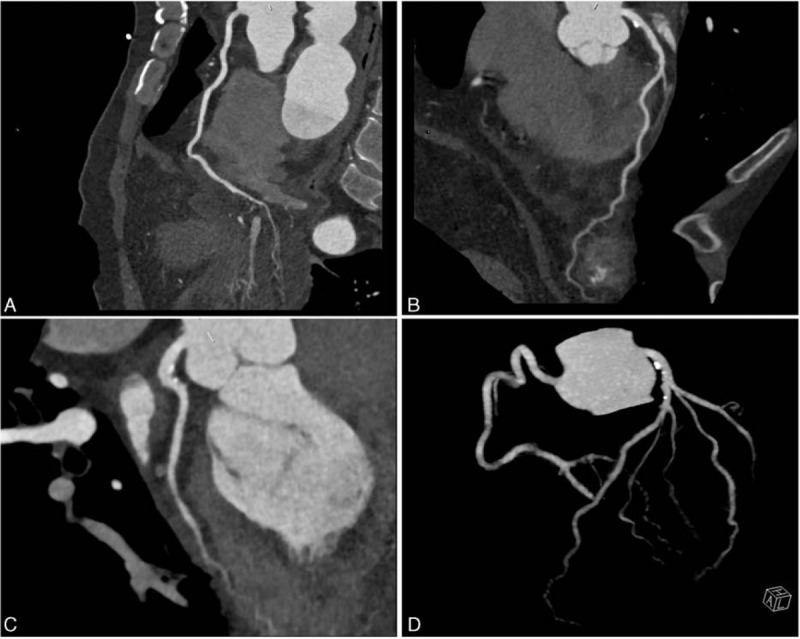

Arterial blood gas analysis revealed pH 7.42, PaO2 51 mm Hg, PaCO2 28 mm Hg. White blood cell count was 18.6 × 109/L with eosinophil cell count 7.6 × 109/L (41% leukocytes), without anemia or thrombopenia. Hypersensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 7.66 mg/dL (normally 0–0.35 mg/L). Serum IgE level was 2540 IU/mL (normally 0–100 IU/mL). Serum troponin I level was increased to 30.54 ng/mL (normally 0.0344 ng/mL), and levels of myocardial enzymes were all increased (aspartate transaminase 150 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 771 IU/L, creatinine kinase [CK] 252 IU/L, CK-MB 38 IU/L, hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 845 IU/L). B-type natriuretic peptide level was 847.3 pg/mL (normally <76 pg/mL) and D-dimer level was 1810 μg/L (normally <590 μg/L). Serum tests were negative for antinuclear antibodies, antimyeloperoxidase (MPO), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Serologic tests were negative for viruses (Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B and C virus, HIV). Screening for parasites was negative. Blood and urine cultures were sterile. Electrocardiography revealed sinus tachycardia (Fig. 1). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a dilated hypokinetic left ventricle (left ventricular ejection fraction ∼40%) with mild segmental abnormalities in the septal and apical segments. The right ventricle was normokinetic and not dilated. Color Doppler ultrasonography revealed moderate regurgitation of the mitral valve. Mild pericardial effusion was present. Coronary CT angiography ruled out severe artery stenosis (Fig. 2). 99mTc-sestamibi MIBI-gated myocardial perfusion imaging (G-MPI) revealed multiple perfusion-decreased foci in the left ventricle, and left ventricular contractile function was impaired. CT scan revealed bilateral ground-glass nodular lung opacities and small pleural effusions. Renal function was normal, with serum creatinine level 67.33 μmol/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate 111.32 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normally >90 mL/min/1.73 m2). Urinalysis gave normal results. Electromyography revealed decreased nerve conduction velocity, representing peripheral neurological damage. Bone marrow testing showed reactive eosinophilia and thrombocytosis.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiography of a 59-year-old man with general fatigue, numbness of limbs, and a 2-year history of asthma.

Figure 2.

Coronary CT angiography of our case. CT = computed tomography.

The diagnosis of CSS was considered according to the criteria (history of asthma, eosinophilia, neuropathy, and pulmonary infiltrates).[5] Immunosuppressive therapy, oral prednisolone 40 mg per day, was started on day 5 after admission to the cardiology unit. Apyrexia was achieved, and eosinophil blood count and CRP and troponine I levels quickly decreased to normal ranges. Symptoms of heart failure were gradually resolved.

After 2-week treatment, the patient's condition improved. He no longer had shortness of breath and no numbness in limbs. The body temperature, eosinophilia, and cTnT level all decreased gradually. The patient was discharged from hospital with treatment consisting of ramipril, bisoprolol, spironolactone, furosemide, and prednisone. On follow-up, the 6-min walking distance was 530 m. One month after diagnosis, the patient was still asymptomatic.

3. Systematic review of available data

3.1. Data search

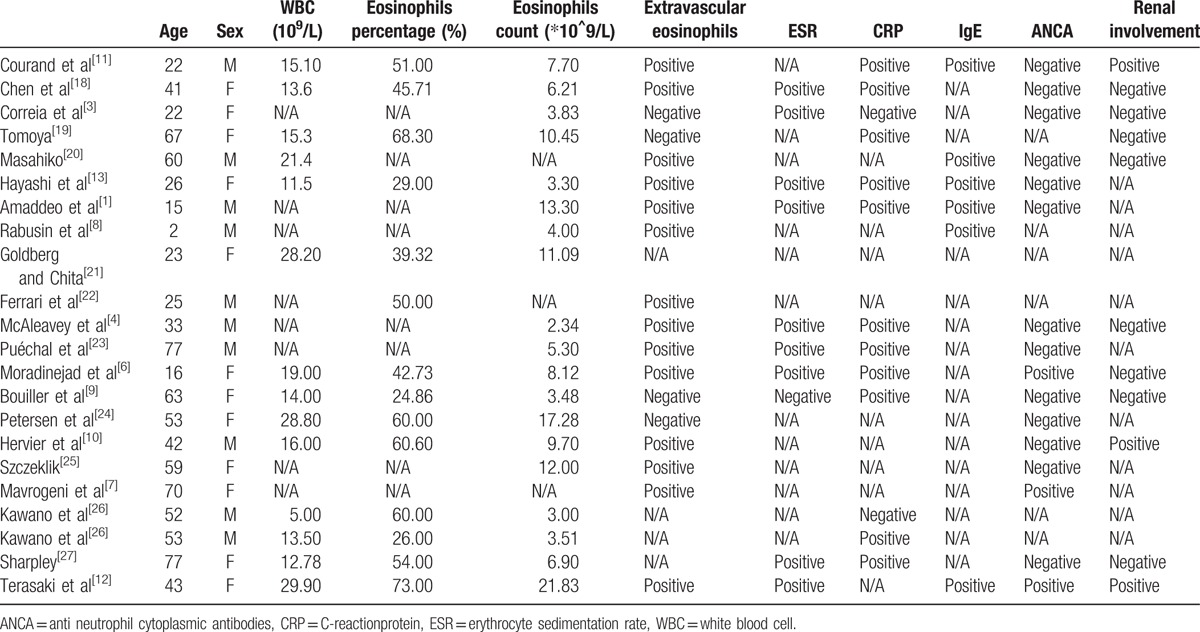

MEDLINE via PubMed was searched for English articles by using the terms “Churg–Strauss Syndrome” AND “myocarditis”; 53 items were found. Articles were included if they (1) were a case report; (2) described a confirmed diagnosis of CSS complicated with myocarditis; (3) were published after 1990 because the diagnostic criteria for CSS were established in 1990; and (4) described no concomitant diseases such as intracranial hemorrhage or systemic lupus erythematosus. The search resulted in 22 articles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

4. Results

Ten of the 22 reported cases involved females and the age at disease onset ranged from 2 to 77 years. Peripheral eosinophilia was reported in all 22 cases and extravascular eosinophils infiltration in 14 of 18 cases. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was positive in 9 of 10 cases and CRP was positive in 10 of 12. Overall, in 8 cases, myocarditis was confirmed by biopsy and pathology and others were diagnosed by imaging. Two patients received leukotriene receptor antagonists and 3 steroids (1 by inhalation, 2 per oral) for asthma.[6,7] Details are in Table 1.

4.1. Age

The mean age at diagnosis of CSS complicated by myocarditis was 42.77 years.[2] The incidence of myocarditis in CSS patients 20 to 30 years old (22.7%) was higher than that for other groups. Acute coronary syndrome in relatively young patients without classical cardiovascular risk factors is suggestive of myocarditis. More studies are needed for the cardiac manifestations of different ages. Given that patients under 20 years are few and the prognosis of pediatric CSS, such as the 2-year-old patient in the Rabusin report,[8] is poor, we propose that the younger the patient with CSS, the greater the occurrence rate of complicating myocarditis, and the poorer the prognosis.

4.2. Sex

Among the 22 patients were 12 males. The mean age of females was 46.67 years, 8.57 years older on average than males (38.10 years). The habits of males, such as smoking, likely have a synergistic effect with eosinophils on the heart[5]. As well, estrogen probably protects the female cardiovascular system against inflammation[9]. Further research is needed to verify and illuminate the protective effect of sex on CSS.

4.3. Eosinophils

White blood cell count increases sharply with the disease (mean = 17.4 × 109/L), probably resulting from the proliferation of eosinophils. The eosinophil percentage in all cases is > 20%, much higher than the diagnostic standard (10%). Eosinophil count in 15 of 19 patients ranged from 2.5 to 12.5 ×109/L, with a mean of 8.1×109/L. Cardiac involvement, especially myocarditis, may be associated with a surge in eosinophils, which may suggest the pathogenesis of myocarditis in CSS patients. Extravascular eosinophil infiltration is due to the significant increase in intravascular eosinophils. When its count increases up to 20% of WBC counts or 8.1×109/L, eosinophils start to infiltrate into myocardium.

4.4. ANCAs

ANCAs are reported in ∼40% of CSS cases,[2,9] the presence associated with increased risk of glomerular disorders, biopsy-proven vasculitis, and peripheral neuropathy and the absence related to heart disease. From our case and the literature, almost all cases with cardiac involvement are usually negative for ANCAs (14 of 16), and 1 ANCA-positive case involves the kidney. To conclude, our CSS patient with a predominant cardiac manifestation and without renal impairment lacked a characteristic ANCA pattern, which agrees with reported findings.[2,9] Only 3 of 22 CSS cases were complicated by renal involvement,[10–12] so myocarditis and renal involvement may be rarely present at the same time, which may be due to the ANCAs.

4.5. Other organ infiltration

According to the reports, 90% of CSS patients with myocarditis have asthma. Asthma is always present in CSS patients, not just those with myocarditis, and this finding helps differentiate it from other entities such as polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener's granulomatosis), or hypereosinophilic syndrome. In any patient with asthma, the diagnosis should be suspected when the case is complicated by at least one of three characteristics: difficult to treat, steroid-dependent, and late-onset disease.[13]

5. Discussion

CSS has an extremely low incidence, ranging from 0.5 to 6.8 new cases per million patients per year and prevalence from 10.7 to 13 per million adults, varying by location and the diagnostic criteria applied. The mean age at diagnosis is 48 years,[14] and both sexes are affected equally. We have little data on race distribution. The diagnostic criteria of CSS require the presence of any 4 or more of the following: asthma, eosinophilia > 10%, neuropathy, pulmonary infiltrates, paranasal sinus abnormality, or extravascular eosinophils.[5] Our patient had had asthma for 2 years, and the eosinophil proportion was > 10% of the white cell count. Furthermore, the numbness of limbs and decreased peripheral nerve conduction velocity represented neuropathy. Finally, the CT scan revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary inflammation foci. Thus, our case met the diagnosis of CSS.

On admission in orthopedics, our patient felt short of breath, had chest congestion, with significant elevation of myocardial enzyme levels, abnormal electrocardiographic pattern, and ejection fraction 41%. We had diagnosed heart failure. Subsequently, electrocardiography findings did not differ from the typical character of acute myocardial infarction, and we did not find responsible vessels on CT angiography. Except for asthma, our patient had no other medical history (e.g., hypertension, rheumatic heart disease), no drug abuse, and no family history. Echocardiography showed no problems of cardiac structure and no valvular vegetations. Notably, continuous eosinophilia and the electrcardiography change led to a diagnosis of myocarditis. Additionally, G-MPI revealed multiple perfusion-decrease foci in the left ventricle, which supports our diagnosis. To explore causes of continuous eosinophilia, we performed laboratory examinations. Allergy (like asthma) responds well to inhaled glucocorticoids. For parasite infection, our patient had no recent contact, and sputum culture did not reveal relevant microbial pathogens. Purified protein derivative and T-spot testing were negative. Furthermore, a consultant physician from the respiratory department suggested that infiltration in lungs was new and had a low risk of infection. Thus, we could exclude tuberculosis infection. Glomerular filtration rate and urea and urine testing were normal, which helped rule out interstitial nephropathy.

The pathophysiology of CSS can be divided into 3 stages. The prodromal stage is characterized by asthma and atopic disease and can last a few years, even as long as 30 years, according to the report. In the next stage, eosinophils infiltrate into tissues such as lungs or myocardium. The final stage is usually the diagnosis and when necrotizing vasculitis appears.[15] The pathogenesis of CSS is not detailed thoroughly. Genetics, environment, and their interactions all play important roles. Several inducing factors, such as infection, drugs, and especially leukotriene receptor antagonists (e.g., montelukast)[16] and vaccinations, have been found responsible for the onset of CSS. Immune functional disturbance and dysregulated release of cytokines have been suggested to be associated with eosinophilic disorders.[17]

Myocarditis is one of the most common cardiac manifestations in CSS, presenting from chest pain and palpitations to life-threatening cardiogenic shock and arrhythmia.[11] Our data suggest that risk of myocarditis is increased in patients between 20 and 30 years old and cardiac manifestations occur later in females than males. CSS patients usually have asthma, whereas leukotriene receptor antagonists may be involved in the onset of CSS.[16] Eosinophil count increases markedly to a level much higher than levels of other diagnostic criteria in patients with myocarditis, and the number of white blood cells also increases due to eosinophilia. Patients are positive for erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP level, indicating an inflammation response, whereas CSS patients with myocarditis are usually ANCA-negative.

CSS usually responds quickly to immunosuppressive therapy, associated with rather good prognosis. Corticosteroids are the first-line therapy, resulting in remission and improved survival. When recurrences are frequent or associated with a serious form of necrotizing vasculitis in organs such as the gastrointestinal tract or the heart, the use of cyclophosphamide is recommended. Such favorable outcomes might not apply to patients with organ system involvement that indicates poor prognosis. The French Vasculitis Study Group has recently revised 5 prognostic factors, the so-called 5-factor score (FFS). The new FFS comprises 4 factors that indicate poor prognosis (age >65 years, cardiac involvement, gastrointestinal manifestations and renal impairment characterized by serum creatinine level >150 mmol/L) and 1 factor that indicates a better outcome (the absence of ear, nose and throat manifestations). According to the revised FFS, the presence of 0, 1 or 2 factors associated with CSS represents necrotizing vasculitis of medium and small vessels, typically characterized by asthma and hypereosinophilia. Multiple systems can be involved in CSS, which easily misleads doctors to other diseases.

We conclude that (1) the younger age of CSS, the greater occurrence rate of complicating myocarditis and the poorer prognosis; (2) female CSS patients are older than male patients; (3) patients with cardiac involvement usually have a history of severe asthma; (4) markedly increased eosinophil count suggests a potential diagnosis of CSS (when the count increases to 20% of white blood cell counts or 8.1×109/L, eosinophils start to infiltrate into myocardium); and (5) negative ANCA status is associated with heart disease in CSS.

In summary, we report a confusing case of dyspnea and numbness finally diagnosed as CSS with cardiac involvement. Symptoms improved and eosinophil count was sharply reduced with oral steroids. In any patient with refractory asthma, we should not neglect the diagnosis of CSS. Effective treatment methods can improve the prognosis if diagnosed in time.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, CK = creatinine kinase, CPR = C-reactive protein, CSS = Churg–Strauss syndrome, G-MPI = 99mTc-sestamibi MIBI-gated myocardial perfusion imaging, MPO = antimyeloperoxidase.

Statement: The ethical approval was not necessary because this was a case report. The informed consent was given.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Amaddeo A, Ventura A, Marchetti F, et al. Should cardiac involvement be included in the criteria for diagnosis of Churg Strauss syndrome? J Pediatr 2012;160:707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mahr A, Mossiq F, Neumann T, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss): evolutions in classification, etiopathogenesis, assessment and management. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Correia AS, Goncalves A, Arauio V, et al. Churg–Strauss syndrome presenting with eosinophilic myocarditis: a diagnostic challenge. Rev Port Cardiol 2013;32:707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].McAleavey N, Millar A, Pendleton A. Cardiac involvement as the main presenting feature in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013: bcr2013009394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg–Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1094–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mohammad-Hassan Moradinejad AR, Vahid Ziaee. Juvenile Churg–Strauss syndrome as an etiology of myocarditis and ischemic stroke in adolescents. Iran J Pediatr 2010;21:530–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mavrogeni S, Tsirogianni AK, Gialafos EJ, et al. Detection of myocardial inflammation by contrast-enhanced MRI in a patient with Churg–Strauss syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2009;131:e54–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rabusin M, Lepore L, Costantinides F, et al. A child with severe asthma. Lancet 1998;351:32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bouiller K, Samson M, Eicher JC, et al. Severe cardiomyopathy revealing antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-negative eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Intern Med J 2014;44:928–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hervier B, Masseau A, Bossard C, et al. Vasa-vasoritis of the aorta and fatal myocarditis in fulminant Churg–Strauss syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1728–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Courand PY, Croisillie P, Khouatra C, et al. Churg–Strauss syndrome presenting with acute myocarditis and cardiogenic shock. Heart Lung Circ 2012;21:178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Terasaki F, Hayashi T, Hirota T, et al. Evolution to dilated cardiomyopathy from acute eosinophilic pancarditis in Churg–Strauss syndrome. Heart Vessels 1997;12:43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].S. Hayashi SF, Imamura H. Fulminant eosinophilic endomyocarditis in an asthmatic patient treated with pranlukast after corticosteroid withdrawal. Heart 2001;86:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yano T, Ishimura S, Furukawa T, et al. Cardiac tamponade leading to the diagnosis of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome): a case report and review of the literature. Heart Vessels 2015;30:841–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosenberg M, Lorenz HM, Gassler N, et al. Rapid progressive eosinophilic cardiomyopathy in a patient with Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS). Clin Res Cardiol 2006;95:289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Harrold LR, Patterson MK, Andrade SE, et al. Asthma drug use and the development of Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg–Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen MX, Yu BL, Peng DQ, et al. Eosinophilic myocarditis due to Churg–Strauss syndrome mimicking reversible dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung 2014;43:45–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tomoya Hara KY. Eosinophilic myocarditis due to Churg–Strauss syndrome with markedly elevated eosinophil cationic protein. Int Heart J 2013;54:51–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Masahiko Setoguchi KO. Myocarditis chronic mild eosinophilia and severe cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2009;73:2355–9.19491508 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Goldberg L, Mekel L, Chita G. Acute myocarditis in a patient with eosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates. Cardiovasc J S Afr 2002;13:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ferrari M, Pfeifer R, Poerner TC, et al. Bridge to recovery in a patient with Churg–Strauss myocarditis by long-term percutaneous support with microaxial blood pump. Heart 2007;93:1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Puechal X, Rivereau P, Vinchon F. Churg–Strauss syndrome associated with omalizumab. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:364–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Petersen SE, Kardos A, Neubauer S. Subendocardial and papillary muscle involvement in a patient with Churg–Strauss syndrome, detected by contrast enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Heart 2005;91:e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].W Szczeklik BS. Heart involvement detected by magnetic resonance in a patient with Churg–Strauss syndrome, mimicking severe asthma exacerbation. Allergy 2010;65:1063–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kawano S, Kato J, Kawano N, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of eosinophilic myocarditis patients treated with prednisolone at a single institution over a 27-year period. Intern Med 2011;50:975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sharpley FA. Missing the beat: arrhythmia as a presenting feature of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014: bcr2013203413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]