Abstract

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is a soluble pattern recognition receptor and an acute-phase protein. It has gained attention as a new biomarker reflecting tissue inflammation and damage in a variety of diseases. Aim of this study is to investigate the role of PTX3 in childhood asthma.

In total, 260 children (140 patients with asthma and 120 controls) were enrolled. PTX3 levels were measured in sputum supernatants using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test. We performed spirometry and methacholine challenge tests and measured the total eosinophil count and the serum levels of total IgE and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) in all subjects.

Sputum PTX3 concentration was significantly higher in children with asthma than in control subjects (P < 0.001). Furthermore, sputum PTX3 levels correlated with atopic status and disease severity among patients with asthma. A positive significant correlation was found between sputum PTX3 and the bronchodilator response (r = 0.25, P = 0.013). Sputum PTX3 levels were negatively correlated with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (r = -0.30, P = 0.001), FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) (r = -0.27, P = 0.002), and FEF25–75 (r = -0.392, P < 0.001), which are indicators of airway obstruction and inflammation. In addition, the PTX3 concentration in sputum showed negative correlations with post-bronchodilator (BD) FEV1 (r = -0.25, P < 0.001) and post-BD FEV1/FVC (r = -0.25, P < 0.001), which are parameters of persistent airflow limitation reflecting airway remodeling.

Sputum PTX3 levels increased in children with asthma, suggesting that PTX3 in sputum could be a candidate molecule to evaluate airway inflammation and remodeling in childhood asthma.

Keywords: allergy, asthma, children, induced sputum, pentraxin 3

1. Introduction

Asthma is the most common chronic airway inflammatory disorder in children, characterized by variable airflow obstruction and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). Asthma typically begins in early childhood.[1] The prevalence of asthma in children has increased and become a major worldwide public health issue.[2] Although diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for childhood asthma are useful in clinical practice, some children with asthma remain undiagnosed or unclassified. Thus, new diagnostic approaches and assessments have been under investigation in childhood asthma, which can be a heterogeneous disease characterized by various clinical symptoms and variable progression of the underlying airway inflammation and structural alterations.[3]

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) acts as a soluble pattern recognition receptor (PRR) involved in innate immunity, and it is a member of the long PTX subfamily. PTX3 is not only known as an acute phase protein but also as a multifunctional protein, and several studies have reported its role in various inflammatory diseases. PTX3 has been studied as an emerging marker reflecting tissue injury and inflammation, such as that caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome,[4] atherosclerosis,[5] small-vessel vasculitis,[6] rheumatoid arthritis,[7] chronic kidney disease,[8] and lupus nephritis.[9] An association between PTX3 and chronic airway inflammatory diseases has been also discovered.[10–14] However, the precise role of PTX3 in chronic lung inflammation has not been established, particularly in children.

This study aimed to determine whether PTX3 plays a role in childhood asthma. We examined sputum PTX3 levels in children with asthma and compared its levels among subgroups of subjects. The relationships between sputum PTX3 levels and other asthma indices, including blood and sputum biomarkers and pulmonary function parameters, were also analyzed.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

In total, 260 children were enrolled who visited Severance Children's Hospital between January 2012 and December 2014. Among them, 140 were diagnosed with asthma on the basis of the American Thoracic Society criteria, which define asthma as recurrent wheezing or coughing in the absence of a cold in the preceding 12 months with a physician's diagnosis, and AHR upon methacholine challenge (PC20 ≤16 mg/mL) or at least 12% reversibility of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after bronchodilator (BD).[15] Among the asthma patients, 72 were diagnosed with intermittent asthma, 35 had mild persistent asthma, and 31 had moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. None of the asthmatic children had a history of acute respiratory infection in the preceding 4 weeks or were receiving maintenance therapy at the time of enrollment. Children treated with systemic corticosteroids due to asthma exacerbation in the preceding month were excluded. The control group consisted of 120 children who had visited the hospital for a general health workup or vaccination and had no history of wheezing, recurrent or chronic diseases, acute infection in the preceding 4 weeks, or hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. Total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, peripheral blood eosinophil count, and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) levels were measured at the initiation of the evaluations. Atopy was defined as >0.7 KUa/L of specific IgE to more than 1 allergen, or >150 IU/mL total IgE, or more than 1 positive skin test among 12 common aeroallergens, including 2 types of house dust mites, cat and dog epithelium, as well as mold and pollen allergens. A specific IgE was measured for 6 common allergens in Korea: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farina, egg whites, cow milk, German cockroach, and Alternaria alternata.[16] This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (protocol no. 4-2004-0036). Informed written consent for participation was obtained from parents, with verbal assent from children.

2.2. Spirometry and methacholine challenge test

Spirometry and methacholine challenge test were performed by standardiazed protocols, as we described previously.[17] Spirometry (VIASYS Healthcare, Inc., Conshohocken, PA) was performed, and flow volume was obtained according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines before and after BD inhalation,[18] In a challenge test, each child inhaled increasing concentrations of methacholine (0.075, 0.15, 0.31, 0.62, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/mL) nebulized by a dosimeter (MB3; Mefar, Brescia, Italy) until FEV1 reduced by 20% from a post-nebulized saline solution value. The bronchial response was expressed as the provocative concentration of methacholine causing a 20% decrease in the FEV1 (PC20; measured in milligrams per milliliter) and was calculated by linear interpolation of the log dose–response curve.[19]

2.3. Sputum induction and processing

For sputum induction and processing, we used the protocol described by Yoshikawa et al.[20] As we described previously,[17] all children were instructed to wash their mouths thoroughly with water. Then, they inhaled a 3% saline solution nebulized in an ultrasonic nebulizer (NE-U12; Omron Co., Tokyo, Japan) at maximum output at room temperature. The children were encouraged to cough deeply at 3-minute intervals thereafter. Spirometry was repeated after sputum induction. If the FEV1 had decreased, the child was required to wait until it returned to baseline values. Sputum samples were kept at 4°C for no more than 2 hours before further processing. A portion of each sample was diluted with a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 10 mmol/L of dithiothreitol (WAKO Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, Osaka, Japan) for cell counting. And then, each sample was gently vortexed for 20 minutes at room temperature. After centrifugation at 400g for 10 minutes, the cell pellet was resuspended. We performed a sputum viability determination with the trypan blue exclusion method to ensure adequate viability. Total cell counts were performed with a hemocytometer, and slides were prepared with a cytospin (Cytospin3; Shandon, Tokyo, Japan) and stained with May–Grünwald–Giemsa stain for differential cell counts. Differential cell counts were performed by 2 observers who were blind to the clinical details and who counted 400 nonsquamous cells. The supernatant of each sample was stored at -70°C for subsequent assay for PTX3.

2.4. Measurement of blood eosinophils, serum total IgE and ECP, and sputum PTX3

Eosinophils were counted automatically (NE-8000 system; Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) in peripheral blood, and the serum total IgE and ECP levels were measured using CAP system (Pharmacia-Upjohn, Uppsala, Sweden). Sputum PTX3 was individually detected with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The lower detection limit of the assay was 0.22 ng/mL.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Numerical variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Normal distribution was determined by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Numerical parameters with non-normal distribution were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Statistical comparison of values between groups was made by the Mann–Whitney U test. The correlation between sputum PTX3 concentrations and numerical parameters (blood eosinophil count; serum total IgE and ECP levels; sputum eosinophil count; and lung function parameters) was determined using Spearman rank correlation test. All comparisons were made by 2-sided. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical software (SPSS, version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Subject characteristics

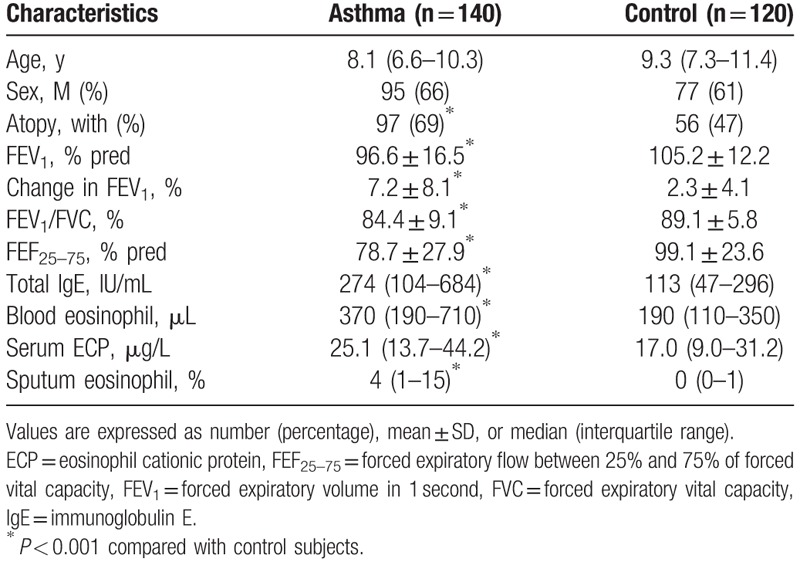

As summarized in Table 1, there were no significant differences in age or gender between the groups. The percentage of children with atopy was significantly higher in the asthma group than in the control group (P < 0.001). Pulmonary function parameters, including FEV1 (P < 0.001), percentage change in FEV1 after BD inhalation (P < 0.001), ratio of FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) (P < 0.001), and forced expiratory flow mid-expiratory phase between 25% and 75% of FVC (FEF25–75) (P < 0.001), showed significantly lower levels in children with asthma than in control subjects. The blood eosinophil count, serum ECP, and serum total IgE levels were increased in children with asthma compared with those in control subjects (P < 0.001), and the percentage of eosinophils in induced sputum was also increased in children with asthma (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects.

3.2. Sputum PTX3 and asthma

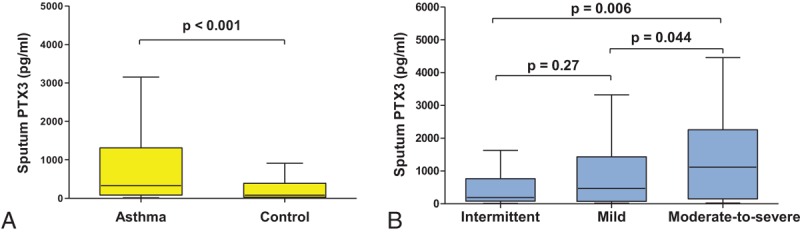

Sputum PTX3 concentration was significantly higher in children with asthma (328.5 pg/mL, 82.34–1312.0 pg/mL) than in control subjects (79.23 pg/mL, 29.09–391.40 pg/mL, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Comparison of sputum PTX3 levels between groups. (A) Asthmatic children had significantly higher levels of sputum PTX3 than the control subjects (P < 0.001). (B) Children with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma showed significantly higher sputum PTX3 levels than those with mild persistent asthma (P = 0.044) and intermittent asthma (P = 0.006). The intermittent asthma group and mild persistent asthma groups were not significantly different (P = 0.27).

Comparing sputum PTX3 levels among the subgroups based on asthma severity (Fig. 1B), children with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma showed significantly higher sputum PTX3 levels (1190.63 pg/mL, 302.70–2619.84 pg/mL) than those with mild persistent asthma (391.72, 73.77–1352.35 pg/mL, P = 0.044) and intermittent asthma (188.15 pg/mL, 80.41–745.08 pg/mL, P = 0.006). The level of sputum PTX3 in the mild persistent group seemed to be higher than that in the intermittent asthma group, but there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.27). There were no significant differences in age or gender among the groups (data not shown).

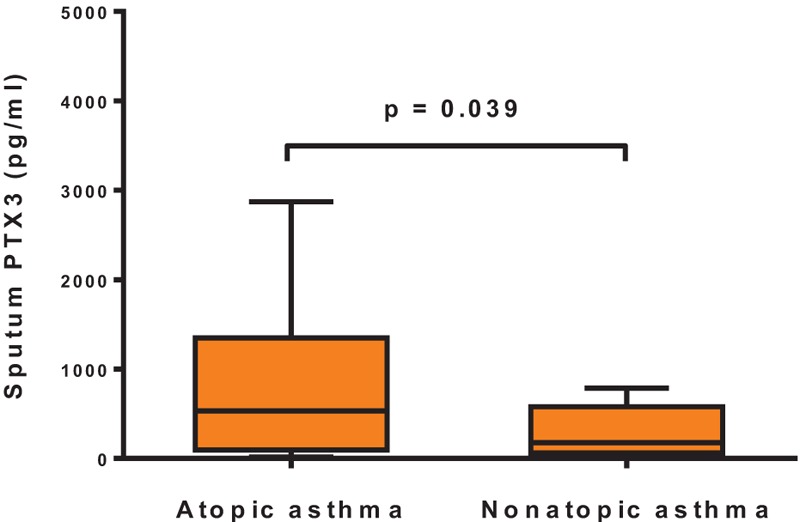

3.3. Sputum PTX3 in atopic and allergic inflammation

Among the asthmatic children, children with atopic asthma showed significantly higher sputum PTX3 levels (533.57 pg/mL, 96.28–1345.87 pg/mL) than those with nonatopic asthma (176.49 pg/mL, 61.64–561.97 pg/mL, P = 0.039) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the sputum PTX3 levels in the control subjects were not different between those with atopy (64.59 pg/mL, 18.52–201.69 pg/mL) and those without atopy (50.70 pg/mL, 23.30–304.36 pg/mL, P = 0.415) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Sputum PTX3 levels according to atopic status in asthma patients. Children with atopic asthma had significantly higher levels of sputum PTX3 than those with nonatopic asthma (P = 0.039).

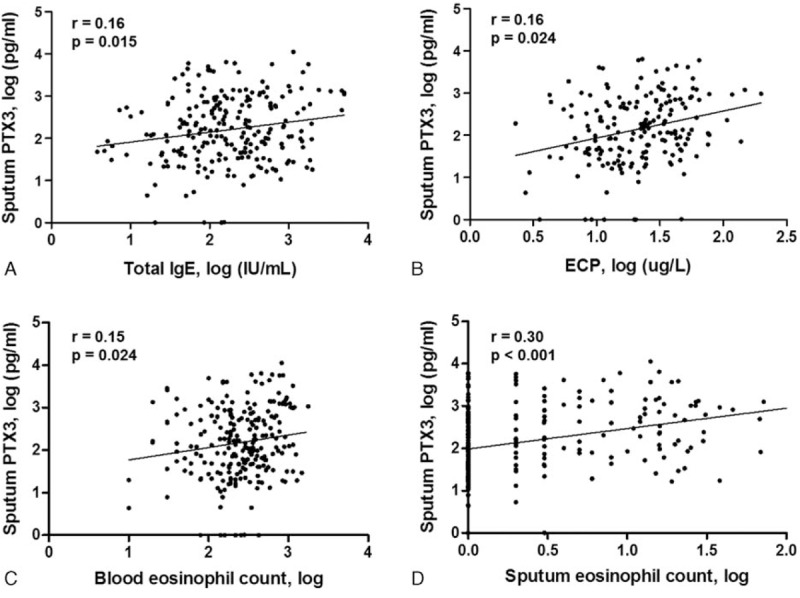

Serum total IgE levels were positively correlated with sputum PTX3 concentrations (r = 0.16, P = 0.015) (Fig. 3A). Significant positive correlations were also found between sputum PTX3 levels and serum ECP (r = 0.16, P = 0.024) (Fig. 3B), blood eosinophil count (r = 0.15, P = 0.024) (Fig. 3C), and sputum eosinophil count (r = 0.30, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Correlation of sputum PTX3 levels with serum total IgE, ECP, blood, and sputum eosinophil counts in asthma patients. (A) Serum total IgE was positively correlated with the sputum PTX3 concentration. Significant positive correlations were also found between sputum PTX3 levels and (B) serum ECP, (C) blood eosinophil count, and (D) sputum eosinophil count.

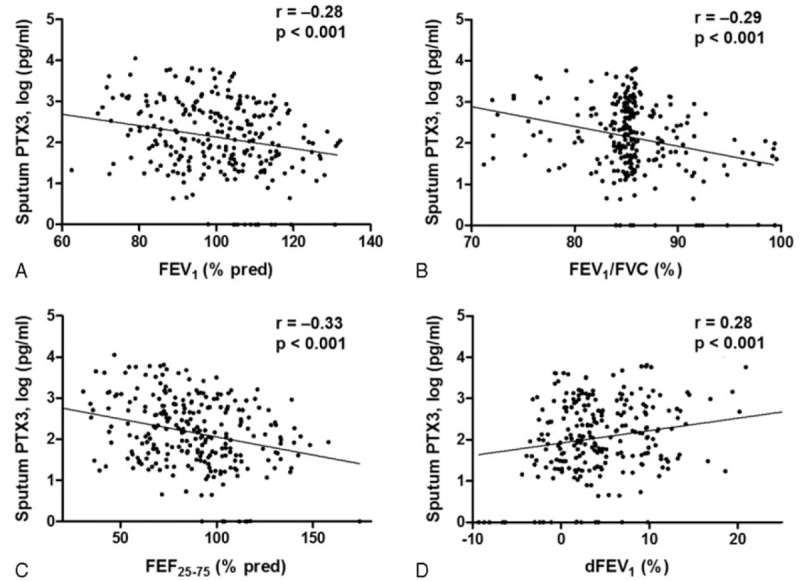

3.4. Sputum PTX3 in pulmonary function and airway remodeling

Significant negative correlations were observed between sputum PTX3 and FEV1 (r = -0.30, P = 0.001) (Fig. 4A), FEV1/FVC (r = -0.27, P = 0.002) (Fig. 4B), and FEF25–75 (r = -0.392, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). Regarding BD response (BDR), significant positive correlation was found (r = 0.25, P = 0.013) (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Correlation of sputum PTX3 concentration with pulmonary function variables and bronchodilator response (BDR). Sputum PTX3 concentrations were negatively correlated with (A) FEV1, (B) FEV1/FVC, and (C) FEF25–75. (D) A significant positive correlation was found between sputum PTX3 levels and BDR.

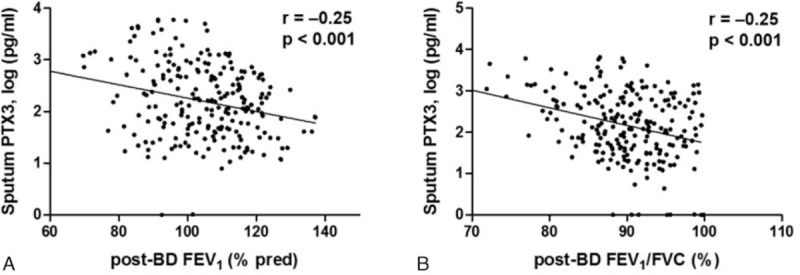

As shown in Fig. 5, the sputum PTX3 levels were also significantly negatively correlated with post-BD FEV1 (r = −0.25, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A) and post-BD FEV1/FVC (r = −0.25, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5B). No significant correlation was observed between sputum PTX3 levels and PC20 in the methacholine challenge.

Figure 5.

Correlation of sputum PTX3 levels with post-bronchodilator (BD) FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. (A) Sputum PTX3 levels showed significant negative correlation with post-BD FEV1and (B) post-BD FEV1/FVC.

4. Discussion

In this study, sputum PTX3 levels in children with asthma were significantly higher than those in controls. PTX3 levels in sputum reflected atopic status and disease severity. In addition, sputum PTX3 levels were correlated with other biomarkers and pulmonary function variables of asthma indicating eosinophilic airway inflammation, decreased pulmonary function, and persistent airflow limitation. Therefore, PTX3 in sputum could be a surrogate marker to diagnose and assess childhood asthma.

PTX3 has been involved in the modulation of chronic inflammatory diseases produced by various cell types in response to proinflammatory signals.[21] Plasma levels of PTX3 were found to be markedly higher in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) than the control.[10] In COPD patients, an increase of sputum PTX3 levels was well correlated with symptom scores.[11] And the PTX3 levels in sputum was an independent biomarker associated with COPD severity.[12] Furthermore, increased PTX3 protein production in bronchial tissue, mainly in airway smooth muscle cells (AMSCs), was initially reported in adult asthma patients.[14] An in vitro study reported that the release of PTX3 from human AMSCs was stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)], and PTX3 enhanced the release of C-C motif chemokine ligand 11 (CCL11)/eotaxin-1, which is an important chemokine in eosinophilic airway inflammation and remodeling. It is inferred that PTX3 may be involved in the pathogenesis of asthma, with the induction of CCL11/eotaxin-1 expression in inflammatory conditions affecting structural alterations in asthmatic airways.[14] However, the association between PTX3 and childhood asthma or involvement of PTX3 in development of childhood asthma has not yet been established.

We found that the sputum PTX3 concentration was significantly elevated in asthmatic children compared with controls, consistent with previous reports in adults. Children with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma showed significantly higher PTX3 levels in sputum than those with intermittent and mild persistent asthma. Among the asthma patients, sputum PTX3 was increased in children with atopy. Sputum PTX3 levels showed significant positive correlations with serum total IgE, ECP, and eosinophil counts in the blood and sputum, which are well-known biomarkers of atopic status, asthma severity, and eosinophilic airway.[21,22]

Current guidelines recommend pre- and post-BD spirometry in children above 5 years of age for diagnosis, classification of severity, and assessment of asthma control.[15] Although FEV1 has been considered an objective and reproducible value for measuring airway obstruction, FEV1 is often normal even in children with uncontrolled asthma.[23,24] Therefore, other pulmonary function variables have been considered. The FEV1/FVC ratio may be a more sensitive indicator of airflow obstruction in children to complement FEV1.[14] Recently, low FEF25–75,which reflects small airway patency, was found to be associated with increased asthma severity in children.[25] BDR, a response to short-acting beta agonist, has been suggested as a surrogate biomarker of airway inflammation to predict clinical outcomes and the response to treatment in children with asthma.[26] In addition, low values for post-BD FEV1 and post-BD FEV1/FVC are regarded as functional markers of structural changes that could reflect persistent airflow limitation.[27] However, pulmonary function parameters are limited by their poor correlations with asthma phenotypes and symptom-based severity in children,[26] and children can have persistent airflow limitations and structural changes regardless of phenotype.[28,29] In addition, general application of bronchoscopy, the gold standard to evaluate airway remodeling is also difficult in children because of its invasiveness. Therefore, there is a need to identify new surrogate markers for use in these patients.

We investigated sputum PTX concentration to determine its applicability for diagnosis, assessment, and monitoring of childhood asthma. Sputum PTX3 levels showed significant negative correlations with FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and FEF25–75 and a positive correlation with BDR. Increased sputum PTX3 levels in asthmatic children could indicate poor lung function, with decreased values for the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio indicating current airway obstruction.[26,30] In addition, low FEF25–75 and increased BDR may predict worse clinical outcomes.[25,26] Sputum PTX3 expression was negatively correlated with post-BD pulmonary function. Previous studies suggest that a low post-BD FEV1 and post-BD FEV1/FVC ratio reflect persistent airflow limitation and irreversible structural changes of the bronchial wall.[27,30,31]

This is the first clinical study to evaluate PTX3 levels in induced sputum of children with asthma. Increased levels of PTX3 in induced sputum could indicate atopic status, current asthma and its severity, and characteristics of asthma, such as eosinophilic inflammation, decreased lung function, persistent airflow limitation, and airway remodeling. These results suggest that PTX3 levels in sputum could be useful for diagnosing and assessing childhood asthma. However, there are a few limitations of this study. We could not investigate the relationship between sputum PTX3 levels and treatment in asthmatic children because asthmatic children did not receive maintenance therapy at the time of enrollment in this study. Furthermore, the correlations between sputum PTX3 and measurements of atopy and pulmonary function were seemed to be weak although statistically significant, which might be due to the limitation of the cross-sectional design. Additional prospective clinical trials are necessary to better understand the clinical utility of PTX3 in the diagnosis, classification of phenotypes, and treatment of asthma in children.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AHR = airway hyperresponsiveness, ASMCs = airway smooth muscle cells, BD = bronchodilator, BDR = bronchodilator response, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ECP = eosinophil cationic protein, FEF25–75 = forced expiratory flow mid-expiratory phase between 25% and 75% of forced vital capacity, FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1/FVC = ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity, FVC = forced vital capacity, IgE = immunoglobulin E, PC20 = provocative concentration of methacholine causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in 1 second, PRR = pattern recognition receptor, PTX = pentraxin.

MJK and HSL contributed equally to this work.

Authorship: MJK and HSL contributed to the study design, procedure, analysis, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. ISS, MNK, JYH, KEL, and YHK assisted with the procedures and data analysis. KWK, MHS, and K-EK supervised the design, procedures, interpretation of data, drafting, and revision of the manuscript.

Funding/support: This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C0234).

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Papadopoulos NG, Arakawa H, Carlsen KH, et al. International consensus on (ICON) pediatric asthma. Allergy 2012;67:976–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Martinez FD, Vercelli D. Asthma. Lancet 2013;382:1360–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vijverberg SJ, Hilvering B, Raaijmakers JA, et al. Clinical utility of asthma biomarkers: from bench to bedside. Biologics 2013;7:199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mauri T, Coppadoro A, Bellani G, et al. Pentraxin 3 in acute respiratory distress syndrome: an early marker of severity. Crit Care Med 2008;36:2302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Savchenko A, Imamura M, Ohashi R, et al. Expression of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Pathol 2008;215:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fazzini F, Peri G, Doni A, et al. PTX3 in small-vessel vasculitides: an independent indicator of disease activity produced at sites of inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Luchetti MM, Piccinini G, Mantovani A, et al. Expression and production of the long pentraxin PTX3 in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clin Exp Immunol 2000;119:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tong M, Carrero JJ, Qureshi AR, et al. Plasma pentraxin 3 in patients with chronic kidney disease: associations with renal function, protein-energy wasting, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:889–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pang Y, Tan Y, Li Y, et al. Pentraxin 3 is closely associated with tubulointerstitial injury in lupus nephritis: a large multicenter cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hamon Y, Jaillon S, Person C, et al. Proteolytic cleavage of the long pentraxin PTX3 in the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Innate Immun 2013;19:611–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schwingel FL, Pizzichini E, Kleveston T, et al. Pentraxin 3 sputum levels differ in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease vs asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;115:485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kurt OK, Tosun M, Kurt EB, et al. Pentraxin 3 as a novel biomarker of inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflammation 2015;38:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Van Pottelberge GR, Bracke KR, Pauwels NS, et al. COPD is associated with reduced pulmonary interstitial expression of pentraxin-3. Eur Respir J 2012;39:830–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang J, Shan L, Koussih L, et al. Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) expression in allergic asthmatic airways: role in airway smooth muscle migration and chemokine production. PLoS One 2012;7:e34965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Program NAEaP. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma–Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:S94–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim YH, Park HB, Kim MJ, et al. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide and impulse oscillometry in children with allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2014;6:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sol IS, Kim YH, Park YA, et al. Relationship between sputum clusterin levels and childhood asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2016;46:688–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, et al. Guidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:309–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yoshikawa T, Shoji S, Fujii T, et al. Severity of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is related to airway eosinophilic inflammation in patients with asthma. Eur Resp J 1998;12:879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bottazzi B, Garlanda C, Salvatori G, et al. Pentraxins as a key component of innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2006;18:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Parulekar AD, Diamant Z, Hanania NA. Role of T2 inflammation biomarkers in severe asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016;22:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Koh GC, Shek LP, Goh DY, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein: is it useful in asthma? A systematic review. Respir Med 2007;101:696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moeller A, Carlsen KH, Sly PD, et al. Monitoring asthma in childhood: lung function, bronchial responsiveness and inflammation. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:204–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rao DR, Gaffin JM, Baxi SN, et al. The utility of forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity in predicting childhood asthma morbidity and severity. J Asthma 2012;49:586–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Galant SP, Nickerson B. Lung function measurement in the assessment of childhood asthma: recent important developments. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;10:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, et al. Risk factors for airway remodeling in asthma manifested by a low postbronchodilator FEV1/vital capacity ratio. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:1480–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Szefler SJ, Chmiel JF, Fitzpatrick AM, et al. Asthma across the ages: knowledge gaps in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:3–13. quiz 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Raedler D, Schaub B. Immune mechanisms and development of childhood asthma. Lancet Resp Med 2014;2:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fitzpatrick AM, Teague WG. National Institutes of Health/National Heart L, Blood Institute's Severe Asthma Research P Progressive airflow limitation is a feature of children with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:282–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Payne DN, Qiu Y, Zhu J, et al. Airway inflammation in children with difficult asthma: relationships with airflow limitation and persistent symptoms. Thorax 2004;59:862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]