Abstract

Ethical issues surrounding the marketing and trade of controversial products such as tobacco require a better understanding. Virginia Slims, an exclusively women’s cigarette brand first launched in 1968 in the USA, was introduced during the mid 1980s to major Asian markets, such as Japan and Korea, dominated by male smokers. By reviewing internal corporate documents, made public from litigation, we examine the marketing strategies used by Philip Morris as they entered new markets such as Japan and Korea and consider the extent that the company attempted to appeal to women in markets where comparatively few women were smokers. The case study of Virginia Slims reveals that the classification of “vulnerable” consumers is variable depending on culture, tobacco firms display responsive efforts and strategies when operating within a “mature” market, and cultural values played a role in informing Philip Morris’ strategic decision to embrace an adaptive marketing approach, particularly when entering the Korean market. Finally, moral questions are raised with tobacco being identified as a priority product for export and international trade agreements being used by corporations, governments, or trade partners in efforts to undermine domestic public health policies.

Keywords: Case study, Culture, Marketing and consumer behavior, Public health, Target marketing, Tobacco, Virginia Slims

Introduction

Tobacco use represents the single most important preventable cause of death in the world; globally, it is estimated that tobacco use will be attributable to more than 8 million deaths, each year, by 2030 (World Health Organization 2008). Smoking accounts for more deaths than HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined (Mackay and Shafey 2006). In the USA, an estimated 443,000 people die prematurely each year as a result of smoking, which represents roughly one of every five deaths domestically (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2012). Although smoking rates are declining in the USA, smoking rates are increasing in many low- and middle-income countries: 70 % of smoking-related deaths are expected to take place in developing countries, and over half of the world’s 1.1 billion smokers live in Asia (Mackay and Shafey 2006).

Given that tobacco is an inherently harmful product, limitations on marketing efforts have been recommended and marketers are advised to use extreme caution strategically, regardless of whether target markets are considered to be sophisticated, at-risk, or vulnerable consumers (Rittenburg and Parthasarathy 1997). Although segmentation is a commonly used strategic approach by marketers generally, the selection of target markets is most likely to undergo criticism when disadvantaged segments of a society are targeted with harmful products. Tobacco firm, R.J. Reynolds underwent considerable scrutiny in the USA, for example, during the late 1980s and early 1990s when launching the Uptown and Dakota cigarette brands, which were specifically developed and targeted toward African-Americans and blue-collar women, respectively (Balbach et al. 2003; Sautter and Oretskin 1997; Smith and Cooper-Martin 1997). While target marketing is a common subject of business ethics—and tobacco marketing, specifically—much of the literature focuses on domestic contexts and demographics as a segmentation variable. To better understand ethical issues relating to controversial products and target market selection, calls have been made for geography as a segmenting variable as well as multinational contexts, including an assessment of whether “tobacco marketers should knowingly sell a product in other countries that is considered harmful in their home country” (Ferrell and Fraedrich 1991, p. 162). Further, more study is needed regarding the role of governments in negotiating trade agreements and opening new markets for product sectors seen as particularly controversial. The function of consumer cultural differences in informing the development of cigarette advertising strategies in international markets has also been identified as an understudied area (Unger et al. 2003).

In this paper, we provide a case study that demonstrates how Philip Morris, the world’s largest private tobacco firm, has marketed its Virginia Slims cigarette brand to consumers both domestically and internationally. Virginia Slims is a well-known women’s niche cigarette brand that was launched in the USA in 1968 and introduced to several Asian countries, including Japan and Korea, during the mid and late 1980s, which reflected considerable pressure from the U.S. government to open such markets to foreign cigarettes. Considering that the majority of Japanese and Korean men have traditionally been smokers, whereas considerably less women smoke, we felt that it would be particularly interesting to examine how Philip Morris’ Virginia Slims—a prominent women’s niche cigarette brand in the USA—was marketed as the brand entered major Asian markets dominated by male smokers.

The central research question guiding our case study is: What marketing strategies were used by Philip Morris as they entered new markets such as Japan and Korea, and to what extent did the company try to appeal to women in markets where comparatively few women were smokers? The public health community expressed considerable concern that entering major Asian markets would provide foreign tobacco companies with an opportunity to reach an untapped market and attract a demographic of new smokers. As will be seen, our case study provides insight about cultural variability regarding how “vulnerable” consumers are defined or classified. Second, our paper demonstrates responsive efforts and strategies by the tobacco industry when operating within a “mature” market. Third, our case study accounts for cultural values concerning whether Philip Morris embraced a standardized or an adaptive marketing approach as they entered the Japanese and Korean markets. Fourth, moral questions are raised with tobacco being identified as a priority product for export and the use of international trade agreements by governments or corporations in efforts to undermine domestic public health policies.1 More recent international trade agreement negotiations, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, include reconsideration by the U.S. government about whether such agreements should possess a general exception for matters pertaining to the protection of public health.

Background

Domestic Market: 1900–1986

At the turn of the twentieth century, cigarette smoking was not the common form of tobacco consumption in the USA; cigarettes possessed a mere 2 % share of the tobacco product category, whereas smokeless tobacco, pipes, and cigars were the common forms of tobacco use. Coinciding with nationwide advertising, the 1913 launch of R.J. Reynolds’ Camel cigarettes was indicative of “mass” marketing being introduced for the cigarette product sector. During the 1920s, American Tobacco, R.J. Reynolds, and Liggett & Myers were regarded as the “Big Three” on the basis of dominating sales for a predominant brand (i.e., Lucky Strike, Camel, and Chesterfield, respectively), with Lorillard also having a market presence with their Old Gold brand. Philip Morris introduced the brands, Marlboro and Philip Morris in 1927 and 1933, respectively, and by 1950 the U.S. tobacco industry was known to comprise the “Big Five” (Brandt 2007). In 1983, Philip Morris overtook R.J. Reynolds to become the largest cigarette firm in the USA (Kluger 1997).

Corresponding with the emergence of “mass” marketing and an increasingly competitive marketplace, cigarette consumption increased substantially. According to Brandt:

“total consumption of tobacco increased dramatically in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1880, at the time of the inception of the modern cigarette, approximately 250 million pounds of tobacco were consumed annually. By the early 1950s, Americans consumed more than 1.5 billion pounds, a five-fold increase. Cigarettes accounted for this rise almost completely … Such massive growth had powerful implications for the economy as a whole. Cigarettes accounted for 1.4 percent of the gross national product and a remarkable 3.5 percent of all consumer spending on nondurable goods” (2007, p. 97).

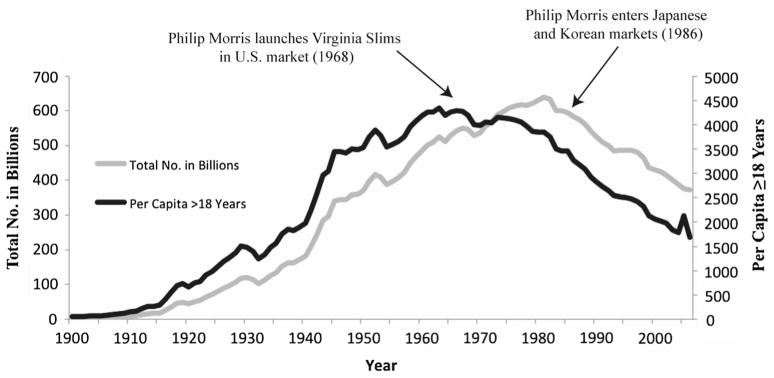

From 1963 to 1981, the total number of domestic cigarette sales increased steadily overall (with some exceptions, including 1964, when the first U.S. Surgeon General’s report to link smoking with cancer was released); 1981 seemingly represented a tipping point as such sales began to decline continuously after that time (Fig. 1). U.S. per capita cigarette consumption, however, has waned continuously since 1973 (Federal Trade Commission 1992).

Fig. 1.

Cigarette consumption in the USA from 1900 to 2006 (total domestic sales and per capita among ≥18 years old). Source U.S. Department of Agriculture (2007)

During the mid 1960s, a majority (i.e., approximately 52 %) of American men were smokers, whereas roughly one-third of women smoked (Federal Trade Commission 1967). With the gender disparity among smoking rates, women represented a considerable market opportunity and American tobacco firms were responsive with product development and the renewed targeting of women. Particularly noteworthy, Philip Morris’ Virginia Slims was introduced to the U.S. market in 1968. The brand’s full national launch was a response to American Tobacco’s Silva Thins cigarette brand, which had been unveiled the previous year. Like “thins,” the “slims” product descriptor referred to a reduced circumference cigarette, which was more slender than a conventional cigarette (Kluger 1997).

To offset declining consumption levels apparent in the U.S. market during the 1980s, American tobacco firms also placed renewed efforts toward expansion in overseas markets. The Cigarette Export Association (CEA) was created in 1981 by Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, and Brown & Williamson with a collective mission to enhance the competitive position of American-produced cigarettes in foreign markets (Brandt 2007). The CEA subsequently brought Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act to the attention of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) in efforts to open foreign markets to U.S. cigarettes. Under Section 301, the USTR could raise retaliatory sanctions against any countries that discriminated against U.S. imports, thus governments in several Asian countries were pressured into allowing the import of American cigarettes (Chaloupka et al. 1996; Kluger 1997). During the mid and late 1980s, the U.S. government placed considerable pressure on several Asian countries—most notably, Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, and South Korea—to open their markets to foreign cigarettes.

Entering Asian Markets: 1980s

Japan, the world’s third largest tobacco market, was the first country in Asia to fully open its market to American tobacco companies—in September 1986—resulting in an immediate and dramatic rise in U.S. cigarette imports, without additional marketing restrictions (Honjo and Kawachi 2000; Knight et al. 2004; Lambert et al. 2004). At this time, roughly 95 % of sales among imported brands in Japan were American, and Philip Morris had a top presence among foreign companies with the introduction of brands such as Virginia Slims, Lark, and Marlboro (Kluger 1997; Mackay and Shafey 2006). In Korea, the world’s eighth largest tobacco market, the import ban was lifted in 1986, initially allowing foreign tobacco companies to acquire up to 1 % of the cigarette market (Lankov 2007; Sesser and Stan 1993). Marlboro was initially introduced to the Korean market, whereas Virginia Slims was introduced in 1988, roughly 2 years later (Philip Morris 1990). Marketing planning and consumer research documents from the tobacco industry, once proprietary but now made public as a result of litigation, offer considerable insight about the strategies used by various tobacco companies.

Methodology

For this paper, we used the case study approach, which aims to research and understand the phenomenon by studying single examples, such as a particular industry or corporation (Ticehurst and Veal 2000). The case study approach is conventionally used for investigating contemporary events or phenomenon, although case studies can be longitudinal, with historical case studies regarded as a particular category of disciplinary orientation (Merriam 2001). The time frame of our case study is the late 1960s to present—roughly a 45-year span—with the starting point indicating when the Virginia Slims brand was initially launched in the USA. The mid and late 1980s is regarded as a focal point of our analysis given the U.S. government placed considerable pressure on several Asian countries, including Japan and Korea, to open their markets to foreign cigarettes during this time period.

Case studies can help generate testable, relevant theory, and those that assess unique or atypical situations may facilitate the development of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Yin 2003). Investigating the consumer research and marketing strategies of tobacco firms is unique from most industries, in view of numerous internal corporate documents, which would ordinarily be considered proprietary, being available to the public as a result of litigation. Reviewing internal tobacco industry documents has become a well-established method for conducting tobacco marketing research, with widely accepted approaches for searching tobacco industry documents thoroughly documented elsewhere (e.g., Anderson, Dewhirst, and Ling 2006; Carter 2005).

Tobacco industry documents were searched online from the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu), which is situated at the University of California, San Francisco, and a variety of search terms were used such as “Korea and Virginia Slims,” “Japan and Virginia Slims,” “target/women,” and “slim cigarette.” When using the search terms “Korea and Virginia Slims,” for example, 274 documents were generated for review, which prompted summary memoranda to be written and common themes were identified.

The case study research method relies on multiple sources of evidence, in which varying data sources serve triangulating purposes (Eisenhardt 1989; Yin 2003). To complement our analysis of corporate documents, we reviewed trade press such as Advertising Age, as well as Virginia Slims print ads from the History of Advertising Archives at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. The advertisement collection has since been transferred to Duke University’s John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History and is available online from the site of the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (see http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads) as well as the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library.

Findings

Virginia Slims: A Brand Explicitly for Women in the U.S. Market

Product dimensions (e.g., Virginia flavor, slim, and extra long) and advertising appeals (e.g., women’s liberation, femininity, confidence, and independence) have both served as important contributors to the brand’s positioning as a cigarette exclusively for women in the U.S. market. The brand name, Virginia Slims, was meant to be rich in meaning for American consumers. Virginia is both a woman’s name and an American state well known for tobacco farming and production (the corporate headquarters of Philip Morris USA is based in Richmond, Virginia). The slims product innovation referred to a reduced circumference cigarette; comparatively, the cigarettes were more slender, being 100 mm long and 23 mm in circumference (Kluger 1997). For the most part, a reflection that female smokers were more likely to manifest health concerns, market research, commissioned by tobacco firms, revealed that women were more apt to accept a new product development (Pollay and Dewhirst 2002). In 1968, James Bowling, a representative of Philip Morris USA, remarked that, “the ladies have led every major cigarette trend in the past 15 years… Our studies show that they were the first to embrace king-sized cigarettes, menthol, charcoal, and recessed filters” (cited in Sanchagrin 1968, p. 26). In 1969, John Landry, vice president of tobacco products marketing at Philip Morris USA, claimed that the initial idea of a thin circumference cigarette did not gain a positive response among market research male respondents, but “it worked beautifully when we added the idea of female orientation” (cited in Hutchinson 1969, p. 76).

The physical properties of Virginia Slims have historically been an element commonly highlighted in the brand’s advertising and packaging, thereby conveying femininity. The Virginia Slims package was narrower than other competing brands with the slimmer and longer cigarettes as content. Market research done for competitor, Brown & Williamson found that slim-shaped cigarettes conveyed two key product benefits—”made for women” and “feminine”—which in turn looked good and made smokers feel special (Tatham Euro 1995). According to British American Tobacco (BAT) documentation, “there is little question that a slimmer product, by its physical dimensions, clearly communicates style-fashion-distinctive-female imagery” (1985, p. 100501606). When developing a slim line extension for one of its established female-positioned brands, BAT claimed that they would “exploit the female characteristics of slims… the female appeal should be implicit but not overt” (1985, p. 100501613). Moreover, Philip Morris conducted market research of a competitor’s ultra-slim brand through consumer testing and interviews with women from Fairfax, VA and Atlanta, GA. During the interviews, it was determined whether such an ultra-slim product had potential appeal to men, and “the answer was an unqualified ‘No!’ from most women” (Ryan and Frank 1987, p. 2057762570).

When Virginia Slims was initially introduced to the market in 1968, it was offered in filtered regular and mentholated versions (Jeb Lee 1969) followed by several line extensions in subsequent decades, including Lights, 120s, Superslims, and Kings (Toll and Ling 2005). When discussing the national launch of Virginia Slims Lights, Philip Morris claimed that “as America’s number one cigarette made just for women, Virginia Slims more than any other brand had a unique opportunity to capitalize on two market trends. Today women make up the majority of low tar smokers. Almost half of all women have switched to a low tar cigarette” (1978, p. 1005064184). According to the annual report of Philip Morris (1979), “With Virginia Slims already the top-selling cigarette made especially for women, Virginia Slims Lights appeals to the growing number of women smokers with a preference for low-tar cigarettes” (p. 2043819554).

The initial promotional spending for Virginia Slims represented a record amount from Philip Morris (Kaufman and Nichter 2001), with John Landry, vice president of tobacco products marketing at Philip Morris USA, claiming that his company was regarded as a “spender” when they had confidence in a newly introduced brand. In 1969, Landry indicated that $5,000,000 was the minimum amount that should be budgeted for 1 year of introductory ads of a new cigarette brand (Hutchinson 1969). Like Marlboro, the Virginia Slims account was held by the Chicago-based Leo Burnett ad agency. Advertising for the brand was initially done on television and radio, and placed in magazines such as Better Homes and Gardens, Life, Look, and Redbook. Spearheaded by Billie Jean King, Virginia Slims began sponsoring women’s professional tennis in 1970, and sampling was also an important component of the initial promotional mix (Benson & Hedges 1968; O’Keefe and Pollay 1996).

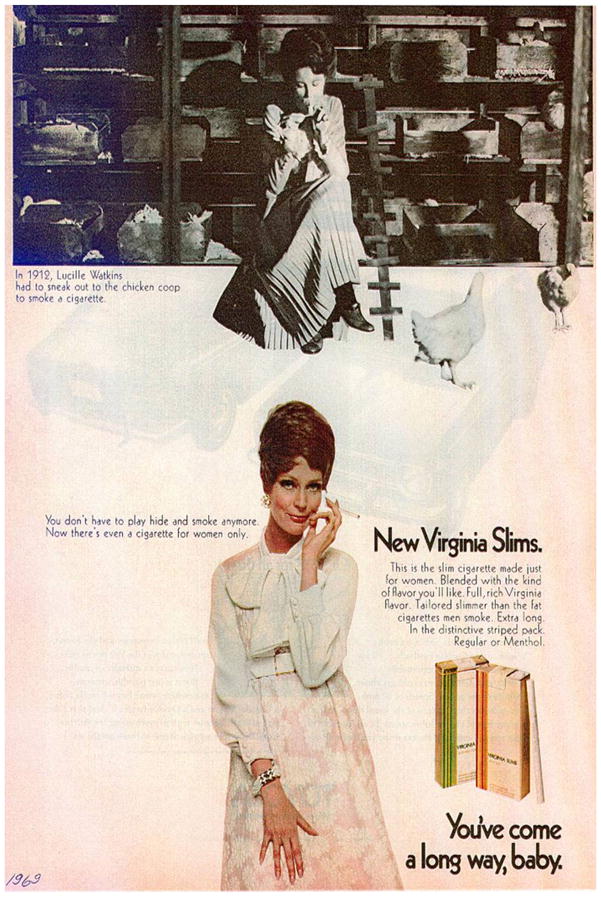

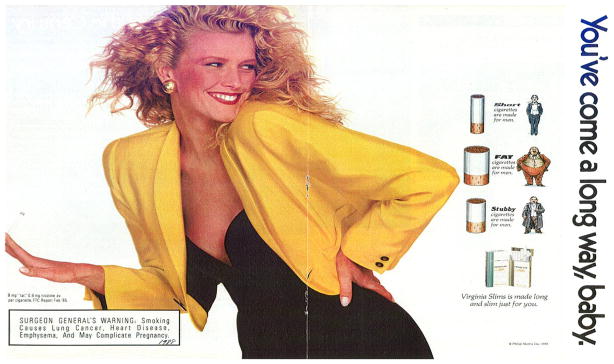

During the late 1960s, initial advertising campaigns for Virginia Slims included the statements, “Now there’s even a cigarette for women only” and “This is the slim cigarette made just for women… Tailored slimmer than the fat cigarettes men smoke. Extra long” (Fig. 2). The ad copy of Fig. 2 also made reference to the brand’s “full, rich Virginia flavor” and distinctive striped packaging. In 1972, ad copy for Virginia Slims advertising claimed that “121 brands of fat cigarettes fit men. Virginia Slims are made slimmer to fit you… They’re tailored slimmer to fit your hands and your lips. With rich Virginia flavor women like.” During the mid 1980s, Virginia Slims advertising maintained that “According to the THEORY OF EVOLUTION, men evolved with fat, stubby fingers and women evolved with long, slim fingers. Therefore, according to the THEORY OF LOGIC, women should smoke the long, slim cigarette designed just for them. And that’s the THEORY OF SLIMNESS.” In 1988, 20 years after the brand’s launch, ad copy continued to emphasize that short, fat, and stubby cigarettes were supposedly for men, whereas long and slim cigarettes were specifically designed for women (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

This ad, which circulated in 1969, identifies Virginia Slims as “new.” In the image seen in the top portion of the ad, the seated woman supposedly sneaked out to the chicken coop to smoke a cigarette. The implied message is that women have made substantial progress since 1912 (when the chicken coop photo was taken), which is represented by contemporary women being able to smoke comfortably in public

Fig. 3.

This two-page Virginia Slims ad, which circulated during 1988, identifies that long and slim cigarettes are supposedly for women. The signature white backdrop of the ad is apparent, which helps accentuate the model with bold clothing, thereby placing her front and center

Philip Morris aimed to achieve a market share of 1 % nationally when Virginia Slims was first introduced (Saleeby 1968). Within 6 months of national distribution, the brand had captured a 3 % share of women smokers (Jeb Lee 1969), and by 1973, Philip Morris’ goals had been surpassed, considering that the brand had a 1.2 % market share of the overall U.S. market (Holbert 1973). When doing a competitive analysis of female-oriented cigarette advertising during the early 1970s, which included Virginia Slims, the Lorillard Tobacco Company stated that “The campaign line ‘You’ve come a long way, baby’ hit the cigarette market in 1968, just as women’s lib was entering the national consciousness. The cigarette is positioned specifically for today’s liberated woman with a unique, swinging image” (Friedman and Valerie 1973, p. 03375510). Virginia Slims was considered to symbolize an overt demand by women for equality.

The market share of Virginia Slims steadily increased from 1968 until the early 1990s (Philip Morris 1996a). The ads demonstrated remarkable continuity, in which a sepia-toned picture depicting a woman from a past time period (usually from the early 1900s) was commonly placed toward the top one-third portion of the ad, while the remaining two-thirds depicted a modern, highly attractive woman that was fashionable and often smiling. The contrasting images were meant to be a lighthearted demonstration that women’s social position had dramatically improved, with the modern woman evidently much happier. Virginia Slims ads commonly portrayed independent women in non-traditional activities, often without the presence of men (frequently one woman was depicted and wedding rings were not apparent). Virginia Slims advertising was commonly placed in magazines such as Cosmopolitan, New Woman, Ladies Home Journal, McCall’s, Family Circle, TV Guide, Ebony, Woman’s Day, Time, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vanity Fair. Explicit statements in the ad copy of the promotions clearly indicated that Virginia Slims was positioned as a product for women, and according to a competitor’s assessment of the marketing environment, the essence of the Virginia Slims brand image was liberated, independent, feminine/modern, style/fashion, active and fun, confident, and pragmatic. Moreover, the brand persona of Virginia Slims was identified as strong, adventurous, and in control, with fashion style deemed as contemporary and casual (Tatham Euro 1995).

According to Roper Research Associates (1970), the typical Virginia Slims smoker was a woman between the age of 25 and 34. One decade later, the profile of the Virginia Slims smoker was becoming younger. The 1980 Cigarette Tracking Study revealed that 93 % of Virginia Slims smokers were women, with 63 % between the ages of 18 and 34. The most pronounced overrepresentation was within the 18–24 age segment (Princiotta 1981). The market share of Virginia Slims was 10.3 % among American women aged 18–24, yet the brand’s market share among the 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 age categories was 6.9, 4.5, 3.4, and 2.1 %, respectively (Holbert 1981). Philip Morris’ 1977 annual report claimed that “during 1977, Virginia Slims grew and consolidated its position as the leading cigarette for women” (Philip Morris 1977, p. 2040357293). Although the market share of Virginia Slims was overrepresented among young women aged 18–24 during the 1970s and early 1980s, between 1985 and 1988 the brand’s market share among younger women (aged 18–24) dropped from 11.1 to 9.3 %, whereas Marlboro and Newport began to attract more of the young female market (Leo Burnett 1989).

Virginia Slims in the Japanese Market

Although Virginia Slims was introduced to the Japanese market in the 1970s, no serious marketing efforts were made until Philip Morris launched Virginia Slims Lights Menthol as the initial line extension in November 1984 (Philip Morris 1985). Internal corporate documentation reveals that the brand was targeted explicitly at women:

“Upon formulating the national introduction program of Virginia Slims Lights Menthol, we have established the marketing objective of capturing share in the female segment in both regular and menthol contexts by introducing a cigarette position[ed] exclusively at women”

(Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012624–2504012625).

According to statistics published in 1984 by the Japan Tobacco Monopoly, approximately 15 % of women in Japan smoked; the female smoker segment in Japan was estimated to represent roughly 14 % of the total market, which was the equivalent of 41 billion cigarettes annually (Philip Morris 1985).

When entering new, international markets, corporations must be mindful about language and translation difficulties, potential cultural misunderstandings, import and ownership restrictions, political uncertainty, economic conditions, and the legal environment. It was acknowledged within Philip Morris’ marketing research that cigarette promotions targeting women were forbidden in Japan:

“…there are several strict restrictions on advertisement against female smokers. These restrictions are more or less imposed by the Japan Tobacco Monopoly as the self restriction and therefore standard of the industry. Specifically, we are not allowed to directly appeal to women nor to show women smoking a cigarette, nor holding a cigarette. However, we are allowed to show women holding a pack of cigarette[s]…We are not allowed to advertise in female magazines nor the magazines whose female audienceship [sic] is greater than 50 %”

(Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012622).

After “meetings with Japan Tobacco Monopoly have confirmed that we must strictly abide by the regulations,” Philip Morris decided against the implementation of a fully standardized U.S. campaign for Virginia Slims in Japan “because we cannot show women in smoking situations” (Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012623). Moreover, Philip Morris observed that the “You’ve come a long way, baby” concept might not translate well to Japanese culture:

“…the ‘You’ve come a long way, baby’ concept itself is almost certain to offend social norms. In Japan, while there are a large number of female smokers who are more apt to smoke cigarettes openly, they are still enjoying smoking almost behind [the] scenes at places such as coffee shops, restaurants, café bars, and so on… Japanese women do not feel comfortable about smoking openly no matter where the situation may be, either in the office or at home”

(Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012623).

Explicitly highlighting themes of women’s liberation might further conflict with traditional Japanese values as well as gender roles that were seemingly more divided; psychographic-oriented advertising studies from 1976 found that Japanese women were more oriented toward the home than their American counterparts (Aaker et al. 1982), and Japanese men are still recognized to traditionally hold nearly all positions of responsibility in business settings (Ball et al. 2004; Wild, Wild, and Han 2006).

Nonetheless, Philip Morris positioned Virginia Slims Lights Menthol as “a new slimmer cigarette designed especially for modern young women” (Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012631). By emphasizing the product characteristics, the campaign developed for Virginia Slims in Japan was designed to appeal to young women and maintain consistency with the U.S. campaign without violating the letter of the voluntary advertising restrictions: “Virginia Slims has uniquely longer and slimmer product, which is made for female hand, and it is suited to the taste of female smokers with its mild flavour and menthol content” (Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012625). The campaign was to feature an American model and “sophisticated international fashion” that appealed to Japanese women:

“With limited budget, cannot show a broad range of fashion. Therefore, critical to zero in on the most appealing fashions.

-

Not too chic

Connotes Ginza hostess -

Not too avant guard [sic]

Connotes young teens -

Middle range

Young working woman at office or play” (Philip Morris 1985, p. 2504012637).

The theme line, translated into “A cigarette, sexy and so slim,” took the form of a Haiku, a traditional Japanese poem (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The ad on the left circulated in the U.S., whereas the corresponding ad on the right circulated in Japan. While the same model (and nearly equivalent photographic image) are used for both ads, the Japanese version does not feature a sepia-toned sequence from a past time period or the “You’ve come a long way, baby” tagline. For the Japanese ad, the cigarette has been removed from the model’s hand and further emphasis is placed on the “Lights” menthol line extension. The bottom portion of the Japanese ad encourages the reader to join the “Virginia Slims Fashionable Club,” with possible prizes to be won such as a BMW car or a trip to San Francisco

During the late 1980s, Philip Morris continued to develop the Virginia Slims campaign targeting Japanese women with television commercials, print advertising, billboards, and direct mail campaigns, as outlined by Robert Roper, vice president of Philip Morris Kabushiki Kaisha (Philip Morris’ Japan division), in a 1991 speech:

“Virginia Slims, with its relatively small, but clearly defined target group is an excellent subject for direct mail activities. This year we will be enlarging our female smoker data base from 30,000 to 60,000 names by expanding the trial and dialogue programs we tested last year”

(Roper and Gatenby 1991, p. 2504038873).

Philip Morris also planned “street level promotions,” a direct mail campaign offering high fashion accessories such as a purse, scarf, or belt, and promotional events including the distribution of free samples in tennis clubs, discos, mountain resorts, and beauty parlors (Knight et al. 2004; Philip Morris 1986; Philip Morris Kabushiki Kaisha 1990).

Virginia Slims advertising research, conducted for Philip Morris in 1991, showed that Virginia Slims was indeed perceived as a female brand:

“Target Imagery

Young women/young women in early 20s/Women in their 20s

Women over 25/women in early 30s

Young ladies out having a good time/healthy young ladies

‘Bright, young things’—young women wearing body-hugging clothing dancing in discotheques

Gorgeous, energetic women/active women who work and live energetically/lively and healthy women who like to play a lot

Women in their 20s who pay a lot of attention to fashion/Stylish young women you see smoking in café/bars

Academic types, personal secretary-types/Long-haired career women who wear suits and high heels” (Philip Morris Kabushiki Kaisha 1991, p. 2504059048).

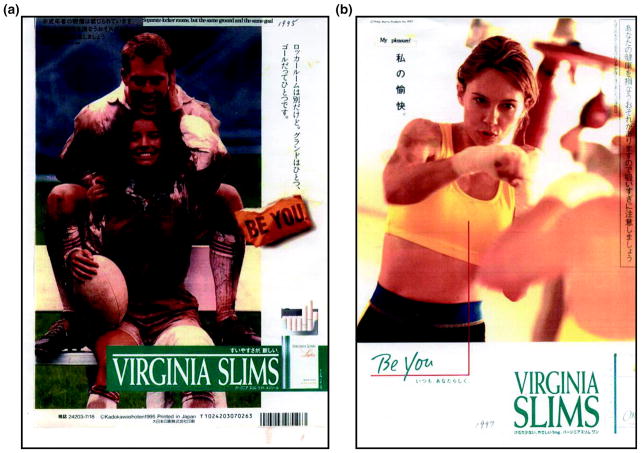

Subsequent ad campaigns during the mid and late 1990s included the tagline “Be You.” An ad, from this campaign in 1994, incorporated copy (in Japanese) that approximately translates to “Purely (as in clean), respectably (as in following societal rules correctly), with a good appearance (as in others think you look cool). I want to hold fast to the rules I’ve created for my lifestyle. But I still am honest with my own feelings. So, I don’t worry about a little lawlessness. Yeah… That’s who I am.” Additional ads from this campaign frequently depicted Western women engaged in non-traditional sports such as boxing and rugby (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The ad on the left, showing a female and male rugby player, circulated in 1995. The Japanese copy states “It’s true that we have separate locker rooms. But there is just one field. And there is only one goal.” Virginia Slims Lights Menthol is the line extension featured, with the ad copy implying that this cigarette has captured an “ease of smoking”. The ad on the right, depicting a woman sparring, circulated in 1997. The Japanese copy, in the upper left side of the ad, states “My indulgence,” while the lower left side copy claims “Be who you are, always.” Virginia Slims One is the line extension featured, with the ad copy claiming “The smoke emitted from the end of the cigarette has been reduced… Not much smoke, gentle 1 mg”. The health warnings depicted in the ads state: “There is risk of damage to your health, so be careful about smoking too much”

These promotional strategies were seemingly successful in terms of sales. Philip Morris International president, William Webb (1990), noted in a draft of his presentation for the Board of Directors that Virginia Slims was the fastest growing menthol brand on the market and estimated sales would reach two billion units that year. Roper, Jr. and Gatenby (1991) also reported that Virginia Slims was their fastest growing brand and estimated it would sell 2.3 billion units by the end of the year. By 1994, Virginia Slims was one of the top ten cigarette brands in Japan, and it shared the leadership position with respect to young adult female smokers, aged 20–24 years (Philip Morris 1994a). Findings from a 2000 cross-sectional survey of university women in Sendai, Japan revealed that Virginia Slims was the third most popular brand in their sample, after Marlboro and Mild Seven (Ohwada and Nakayama 2003).

Virginia Slims in the Korean Market

Virginia Slims was introduced to the Korean market in 1988. During the early stages of Philip Morris’ entry into the Korean market, the company acknowledged that Korean smokers tend to prefer lower (machine-measured) tar and nicotine products that are complemented with promotional appeals relating to luxury. Korea was identified by Philip Morris as one of the lowest tar delivery markets in the world (Philip Morris 1989a). Thus, Philip Morris felt that their Virginia Slims Lights brand would be favorably received in Korea (Philip Morris 1989b). The company, however, faced an interesting dilemma with respect to the brand’s positioning because smoking prevalence among Korean men was roughly 65 %, while it was less than 5 % among women (Mackay and Eriksen 2002). Moreover, the highest incidence of smoking among women was found among the oldest age segment monitored by Philip Morris: 55 years and older (Philip Morris 1990). Similar to Japan, a voluntary code stipulated that cigarette ads could not be directed overtly toward women in Korea, and women were not allowed to be shown smoking in the promotions (Shafey et al. 2003).

While Philip Morris (1990) acknowledged that Virginia Slims Lights was a luxury brand more likely to appeal to women, the brand profile in Korea was identified as “male, in line with the market and appeals most to those aged 30–39 with high school educations and above average family incomes. Demographically its profile is similar to YSL [Yves Saint Laurent, an imported competitor] but it attracts an above average share of starters and more switchers” (p. 2504034036). Consequently, Philip Morris demonstrated an “extreme makeover” strategy for the positioning of Virginia Slims in Korea, and the brand’s advertising has been targeted toward Korean men rather than women. Unlike other major markets, Virginia Slims is first and foremost a male brand in Korea (i.e., 94 % of Virginia Slims consumers are male, while 6 % are female), and the brand largely appeals to males who are older, health conscious, and possess an above average income (Philip Morris 1993). According to a presentation given by W.H. Webb, President and Chief Executive Officer of Philip Morris International, “I have to admit our business is not always free of surprises. There [Korea], the brand has a strong male appeal” (Philip Morris 1994b, p. 2072010561).

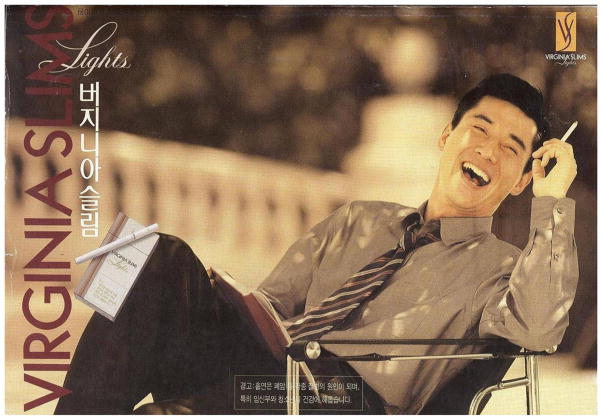

During the 1990s, internal Philip Morris documentation revealed that Korean Virginia Slims advertising was utilizing a “pack as hero” format and a unisex proposition (Webb 1990). Meanwhile, several Korean ads proclaimed, “Virginia Slims: The cigarette for the successful man” (Cho 1997). The ads have commonly depicted male models and circulated in magazines, such as Monthly Chosun and Sisa Journal, which have a predominantly male readership (Fig. 6). In Fig. 6, a Korean businessman is presumably depicted at the forefront, in which he is reading during a time of leisure, given his posture, his apparent laughing, the top button of his dress shirt being unbuttoned, and his tie being loosened. The reader of Monthly Chosun, where this ad circulated, is likely to identify with the model’s appearance, particularly since many readers would be businessmen and wear suits frequently (nearly daily). The background, which is blurred, resembles a mansion with a grand stairway and garden that has a Western appeal and communicates wealth and prestige.

Fig. 6.

This Korean Virginia Slims ad circulated during 2000. The ad copy indicates the brand name in both English and Korean; the Korean copy, which is read from top to bottom (unlike the English copy), states “Virginia Slim.” The singular use of “slim” likely reflects that plural reference to “slims” does not sound as pleasing phonetically. Otherwise, the Korean text is a mandated health warning (i.e., “Smoking causes lung cancer and other illnesses/diseases. In particular, [smoking] damages the health of pregnant women and youth”)

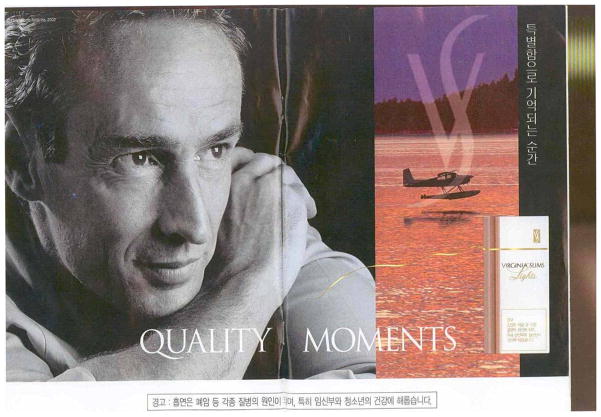

Other Korean Virginia Slims ads have portrayed individual males, as well as the product, with the tagline “Quality Moments” stated in both Korean and English (Fig. 7). The ad shown in Fig. 7 was recognized with an advertising award, sponsored by HanKyung Business Weekly, in 2001 (Kim 2001). The ad’s simplicity, with a black and white contrast, was largely credited for this honor. A second Korean ad from the “Quality Moments” campaign depicted a Western model (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

This particular Virginia Slims ad received a prestigious Korean advertising award during 2001. The ad features the English tagline, “Quality Moments,” whereas the Korean copy implies: “The moment you remember as very special.” One interpretation of the ad is that the Korean model is daydreaming about a special and highly enjoyable moment (i.e., fishing in a relaxing setting with a spectacular sunset). An additional interpretation is that the moment of smoking Virginia Slims is relaxing and enjoyable like the experience of fishing. A Virginia Slims package is depicted with a gold ribbon (tear tape) free flowing, which is likely to draw the reader’s attention, and implies how the package is initially opened, and signifies excellence

Fig. 8.

A Korean ad from the “Quality Moments” campaign, which circulated in Sisa Journal during 2002, that depicts a Caucasian man. Like Fig. 7, the ad features the English tagline, “Quality Moments,” whereas the Korean ad implies: “The moment you remember as very special.” The model appears casual; the depicted moment features a seaplane, which is typically used for light duty transportation to lakes and other remote areas. The setting of the scene is highly unlikely to be in Korea. Sisa Journal is a Korean language publication, thus the reader would likely be Korean rather than a foreign traveler

Although Virginia Slims has largely been a success story in Korea, the brand’s initial market entry proved challenging. The introduction of foreign tobacco to Korea prompted several volatile demonstrations that were typically anti-American in sentiment. Philip Morris acknowledged that foreign tobacco signs were defaced and that their retailers were being harassed. Not only were Korean consumers initially hesitant to purchase foreign cigarette brands, they were “proud” purchasers of local products. The total market share for foreign brands was merely 2 % after 6 months (Philip Morris 1989b). Over time, however, the market share held by foreign tobacco brands improved (Table 1), and Virginia Slims has been a strong performer among the foreign segment. In 1993, Virginia Slims had a 13 % share of the foreign tobacco market within Korea (Philip Morris 1993), and by October 1996 it had become the segment leader with a 33 % market share (Cho 1997). W.H. Webb, in a presentation entitled, “Staying Ahead in the International Tobacco Market,” declared that “Virginia Slims is also our largest selling brand in Korea” (Philip Morris 1994b, p. 2072010561). Philip Morris’ market research indicates that the major contributing factors to the growth and popularity of Virginia Slims in Korea are the product’s taste, slimness, length, prestige, and “light” image (Philip Morris 1989a, 1993). In a separate study on consumer perceptions of cigarette brand images, Virginia Slims was regarded as a “light” cigarette, with appealing packaging, that was contemporary, modern, American, and prestigious. One key challenge with marketing Virginia Slims in Korea was that many Koreans found the brand name fairly difficult to pronounce (single syllable brand names such as Kent and Lark were much easier) (Philip Morris 1990).

Table 1.

The trend of market share in South Korea by cigarette firm

| Cigarette manufacturer | Year

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 (%) | 1993 (%) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | |

| KT & G | 94.6 | 93.4 | 91.1 % | 87.6 % | 89.0 % |

| Japan Tobacco | 2.4 | 3.0 | NA | NA | 6.2 % |

| Philip Morris | 1.2 | 2.0 | NA | 5.8 % | 3.0 % |

| RJ Reynolds | 1.0 | 0.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| Brown and Williamson | 0.5 | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA |

Source Kim (1998)

NA indicates that market share data is “not available.”

Discussion

Virginia Slims is positioned to target exclusively women in the U.S. market as shown in its product dimensions and advertising appeals. To counteract the declining U.S. market in the 1980s, Philip Morris, like other American tobacco firms, made a determined effort to expand in international markets. With the help of the U.S. government, American tobacco firms successfully entered sizable Asian markets such as Japan and Korea. Due to regulatory and cultural differences in these new foreign markets, Philip Morris implemented an adaptive marketing approach for their Virginia Slims brand, including a drastic strategic change in Korea, where the brand is targeted toward men.

Our case study reveals four key themes—(1) vulnerable and at-risk consumers; (2) mature markets and marketing management responses; (3) gender, culture, and smoking; and (4) trade agreements, harmful products, and acknowledging public health—that are discussed further in turn.

Vulnerable and At-Risk Consumers

Defining “vulnerable” or “at-risk” consumers in different markets is complex and it is suggested that culture plays a role in how consumers are accordingly classified. In 1964 and preceding the launch of Virginia Slims cigarettes, self-regulatory standards, known as the Cigarette Advertising Code, were set up in the USA by the major tobacco firms. The Code’s stated purpose was to establish consistent advertising standards for cigarettes and confirmed that cigarette advertising and promotions should not be directed to those less than 21 years old. The Code also stipulated that models appearing in cigarette advertising should be at least 25 years old (and not seem younger) and cigarette advertising should not be placed in comics or in school, college, and university settings (“Text of cigarette industry’s new code” 1964). The Code underwent modifications over time, but in 1990 the stipulations pertaining to age and target marketing remained the same (see Richards et al. 1996). The Code emphasized that smoking is a ritual for adults only, but did not specify other considerations with respect to target marketing. Moreover, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which took effect in 2009 and places the regulation of tobacco marketing under the authority of the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) with the aim of protecting public health, identifies a focus on “young people,” given that “virtually all new users of tobacco products are under the minimum legal age to purchase such products.”

Tobacco regulation in the USA has commonly identified “young people” as worthy of protection, which reflects that smoking initiation is highly likely to take place during adolescence as well as concerns about the influence of advertising among an age group seen as particularly impressionable. Additionally, the marketing literature commonly classifies vulnerable consumers as “those who may not fully understand the implications of marketing messages” (Rittenburg and Parthasarathy 1997, p. 52) and the consumer’s age—and therefore their likely level of cognitive development—is frequently considered a key determining factor (e.g., McAlister and Cornwell 2009; Pechmann et al. 2005). Commonly cited examples of vulnerable consumers are children whereby they may not have sufficient cognitive abilities and defensive mechanisms to fully comprehend the persuasive or potentially manipulative intent of marketing messages. Given such definitions, allowing for a subset of adult consumers to be regarded as “vulnerable” has been somewhat controversial (Smith and Cooper-Martin 1997). For Rittenburg and Parthasarathy (1997), consumers are classified as “at-risk” if they have sufficient cognitive abilities and defensive mechanisms to be regarded as sophisticated, yet possess other disadvantages such as low socioeconomic status or being prone to addiction or compulsive behavior.

As our findings demonstrate, however, gender was also an important consideration of target marketing according to self-regulatory standards established in Japan and Korea. Self-regulatory codes for both countries during the mid 1980s stipulated that cigarette advertising could not be targeted overtly at women or depict women smoking. In Japan, cigarette advertising restrictions remain voluntary, being pursuant to the Tobacco Business Act, which is in effect a form of self-regulation (Japan Tobacco Inc. 2013). In Korea, federal legislation—in accordance with the National Health Promotion Act and the Tobacco Business Act—continues to specify that women and teens should not be targeted by cigarette advertising (Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea 2008). Moreover, the health warnings, as seen in Figs. 6, 7, and 8 (cigarette advertisements circulating in Korea), state “Smoking causes lung cancer and other illnesses/diseases. In particular, [smoking] damages the health of pregnant women and youth.”

Women in Japan and Korea have been identified as a subset of consumers that should be protected, even though they do not appear to be an “at-risk” group with their smoking rates being very low compared to men. With self-regulatory codes being in place before the import of American cigarettes in Japan and Korea, the stipulations disallowing the overt targeting of women with advertising seemingly reflected cultural taboos surrounding women smoking and more general cultural norms regarding the “protection” of women. In Japan, traditionally when women smoke, they were considered unfeminine. This social stigma toward women’s smoking and corresponding regulation was based on the belief that motherhood is the aim of a woman’s life and smoking was harmful to children (Gaouette 1998). In Korea, government regulation may be rooted from neo-Confucian philosophy that has prevailed since the fifteenth century (Turnbull 2010). Social codes related to superior–inferior relationships can often govern how people interact with each other. When superiors are present, it has often been regarded as inappropriate for inferiors to enjoy themselves (with smoking) and to even pursue physical comfort; moreover, superiors have authority over inferiors and control social space (Dredge 1980). Superior–inferior relationships are defined by age, education, socioeconomic status, as well as gender.

Mature Markets and Marketing Management Responses

As Philip Morris entered the Japanese and Korean markets, adhering to the self-regulatory codes in place could be seen as an expression of cultural sensitivity and a public relations move that sought to reassure that their advertising would not attempt to recruit new users and instead be directed toward existing smokers. Tobacco industry representatives commonly claim that its marketing communication is directed toward a “mature” market of existing smokers. From such a viewpoint, tobacco advertising does not influence overall consumptions levels, but rather affects the market share of each cigarette brand. According to the Tobacco Institute, “Tobacco advertising does not cause people to smoke. The contention that it does overlooks the function of advertising in a mature product market, which is to maintain customer loyalty and to get consumers to switch brands” (undated, p. TI16952621).2 Highly consistent with such argumentation, internal corporate documentation from Philip Morris (1994c, p. 2025834361) describes, for public relations purposes, how advertising supposedly works in a “mature” market.

Nevertheless, most products are considered to be in the mature phase of the product lifecycle and subsequent marketing management decision making is not unique to the tobacco industry in this regard. Facing such challenges, common marketing thought, strategically speaking, is to modify the product or market in efforts to increase consumption by attracting new users or enhancing usage among present customers (Kotler et al. 2005), which runs counter to tobacco industry argumentation.

The case study of Philip Morris’ Virginia Slims demonstrates both strategically recommended marketing management approaches being used. First, the product was modified by introducing reduced circumference cigarettes and offering new brands that were positioned to appeal to new users as well as a segment with more growth potential; the strategic product launches of “slim” cigarettes, targeted to women in the U.S., coincided with per capita cigarette consumption beginning to wane. In an attempt to appeal to the increasingly important female demographic, cigarette brands were developed with attributes and personalities meant to be favorable to the needs and desires of the target market (Carpenter et al. 2005). The late 1960s are regarded as a defining period for the proliferation of women’s niche cigarette brands in the USA and a corresponding increase in smoking prevalence among young women (Pierce and Gilpin 1995; Pierce et al. 1994). According to internal corporate documentation during the early 1970s from competitor, Lorillard, “the growing importance of the female smoker is due to several factors, including fewer females quitting, more females beginning to smoke, and female smokers increasing their daily cigarette volume” (Friedman and Valerie 1973, p. 03375506).

Second, the market was modified and new market segments were sought as U.S. cigarettes were introduced to the Japanese and Korean markets during the mid 1980s while domestically the total number of domestic cigarette sales declined. Philip Morris undoubtedly viewed their entry into Japan and Korea as great market opportunities; during a 1989 presentation held in New York City, John Dollisson, the Director of Corporate Affairs of Philip Morris Asia and soon-to-be Vice President, Corporate Affairs of Philip Morris International, indicated, “U.S. cigarette exports to Asia account for close to 70 % of our volume and 97 % of our profits. Furthermore, future growth is likely to come from export markets such as Japan, Taiwan, Korea and Thailand” (1989, p. 2500101312). Philip Morris International continues to offer cigarettes in more countries globally, and in 2008, despite a worldwide recession, sales increased 13 % to $26 billion and profits soared 14 % to $7 billion (Byrnes et al. 2009). According to Christian Eddleman, an analyst from Argus Research, “If these guys were in any other industry, theirs would be pointed to as the way to execute a long-term strategy” (cited in Byrnes et al. 2009, p. 39).

In pursuing new market segments geographically, the review of Philip Morris documentation reveals that “young women” are the target market for Virginia Slims in Japan, which contravenes self-regulatory codes. Virginia Slims advertising in Japan has possessed a parallel target market, linked the brand with fashion, and communicated a similar brand essence to what has been historically observed in the USA. Referring to Fig. 4, the same model and nearly equivalent photographic image were used for advertising in the U.S. and Japan, yet the use of a traditional Haiku poem, the absence of an “old fashioned” versus “new fashioned” dialectic, the omission of lit cigarettes, and an alternative tagline to “You’ve come a long way, baby” exemplify efforts to have local relevance in Japan and circumvent the spirit of self-regulatory stipulations. For the company’s Marlboro brand, the marketing planning documents of Philip Morris Kabushiki Kaisha (1994) and Takarabe (1994) reveal the tracking of smokers classified as “starters.” Market research for Philip Morris International (1992) identified Japan as a mature or declining market generally, but the country was regarded as a stable or growing market with respect to “starters,” who were considered an important contributor to overall market volume.

Philip Morris (1990, 1993) also thoroughly tracked “starters” in Korea, and noted within a market research summary that “the market is predominantly male, but the female segment should grow as females now form 14 % of starters. This is, therefore, a development opportunity” (1990, p. 2504034053). Nevertheless, the Virginia Slims brand has been targeted toward male consumers. Among imported brand profiles in Korea, Philip Morris’ Marlboro Red (i.e., the parent brand) was regarded “by far the youngest franchise… The brand has a very high share of starters” (1990, p. 2504034036). According to a summary of Philip Morris’ market research findings, “the imported brands that appeal most to the prime target market, starters and young adult smokers, are Marlboro Red and Mild Seven… Marlboro Red appears to have significant expansion potential among starters and young adults who are interested in full flavor king size cigarettes with cork tipping in a box” (1990, p. 2504034054–2504034055). Philip Morris’ strategic interest in “starters,” as revealed in their internal corporate documentation, clearly contradicts the “mature” market hypothesis they have put forward.

Gender, Culture, and Smoking: The Masculine/Feminine Dichotomy of Cigarettes

Globalization relates to economic growth and has contributed to the appearance of a global culture, thereby reducing the boundaries between national cultures and economies (e.g., Cleveland and Laroche 2007), but our case study suggests that national cultural differences remain apparent and still matter from a strategic standpoint. Our case study highlights the underlying importance of recognizing different cultural values when attempting to understand smoking behavior and suggests that the product features and advertising images contributing to the masculine–feminine dichotomy of cigarette brands are likely to differ according to the cultural context. In the U.S. market, brands offering relatively high tar content and strong flavors are commonly perceived as “masculine,” with corresponding promotional appeals often having an action, excitement, and adventure orientation. Conversely, supposed low tar, mild taste, longer length, and slim cigarettes are characterized as “feminine” product characteristics, which often carry image platforms relating to relaxation, stress relief, self-indulgence, and women’s independence (Carpenter et al. 2005; Dewhirst 2008; National Cancer Institute 2008; Pollay and Dewhirst 2002; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2001). Yet, consumer research by Philip Morris found that the slimness, taste, and luxurious image appeals of Virginia Slims were desirable product attributes for male smokers in Korea, and the brand’s ads have commonly portrayed relaxation-oriented appeals.

One rationale for why Philip Morris would consider the contrasting positioning of Virginia Slims in Japan and Korea seems to reflect, to some extent, the different cultural values of these nations, with the masculinity/femininity dimension of cultural variability having potential relevance. According to Hofstede (1991, 2001), both the USA and Japan are regarded as “masculine” nations, yet Korea is classified as a “feminine” nation. De Mooij (1998) reasons that products perceived as “foreign” are likely to be more appealing in “masculine” cultures, and Philip Morris documentation shows that, during the early stages of entering the Korean market (a “feminine” culture), many consumers had an anti-American outlook and were loyal to Korean or local brands. Additionally, people from masculine cultures are likely to be agreeable with the desirability of standing out in a crowd, yet this is not commonly a part of the psyche for those from feminine cultures. Placing emphasis on the thrilling aspects of an activity is also advised in masculine countries (Milner and Collins 2000). In contrast, Virginia Slims advertising in Korea placed emphasis on “Quality Moments” and depicted males during instances of leisure (e.g., reading a book, fishing), contentment, and had narratives related to calmness and relaxation. For nations classified as “feminine,” both men and women are expected to be tender, modest, and concerned with relationships and quality of life. The emotional roles of men and women are more equally divided in feminine cultures, with men also being receptive toward ego effacing or social goals. Prevailing norms in feminine cultures include embracing the notion that small and slow is beautiful (Hofstede 1991, 1998).

In Japan, however, the “Be You” ad campaign possessed a tagline and copy that was more bold and assertive, and the ads reflected competitiveness and the potential desirability of standing out in a crowd (i.e., women were engaged in non-traditional sports such as boxing and rugby, albeit the models depicted were Caucasian). These ad appeals are likely to hold particular interest in “masculine” cultures such as Japan, and it is postulated that narratives relating to risk taking and alpha masculinity may not hold as much appeal or resonance among Korean men relative to American or Japanese men. Although men commonly play an ego-boosting role in “masculine” cultures, whereas women tend to place emphasis on ego effacing or social goals, we speculate that the divide in emotional gender roles, combined with equity, mutual competition, and performance being encouraged in the workplace, may be suitable settings for introducing niche brands associated with female empowerment. De Mooij and Marieke (2005) argues that value paradoxes are commonly evident in cultures and advertising (e.g., equality is a core value in the USA, even though the gap between wealthy and poor is widening), which reflects the dilemmas consumers repeatedly face about the desired in life versus what actions one ought to take.

Millward Brown has historically done a considerable amount of brand and marketing research for Philip Morris. Hollis (2008), the Chief Global Analyst at Millward Brown, recognizes masculinity/femininity for being insightful about consumer behavior, brand preferences, and strategic marketing communication. Although explicit mention of the masculinity/femininity dimension is not apparent in the strategic planning documents of Philip Morris, Hollis is identified internally by the company as a well known and impressive speaker (Philip Morris 1996b, p. 2063716795). When discussing culture and advertising, Hollis comments that “differences matter… The potential influence of local culture on the success of global brands is enormous and cannot be underestimated” (2008, p. 89).

The use of Hofstede’s masculinity/femininity dimension of cultural values holds intriguing appeal for examining how brands are marketed to consumers internationally, especially given this dimension distinguishes among various Asian nations such as Japan and Korea (unlike additional dimensions of cultural variability such as individualism/collectivism). It is important for business stakeholders to refrain from hastily considering Asia as a collective market, in which nations are superficially regarded as a shared culture. The masculinity/femininity dimension has been commonly applied for the purposes of business ethics research (e.g., Armstrong 1996; Christie et al. 2003; Davis and Ruhe 2003; Lu et al. 1999; Swaidan 2012), but we nevertheless acknowledge that Hofstede’s dimensions have been criticized for being designed to measure work-related values for a single company (i.e., IBM) and, consistent with consumer culture theorists (Arnould and Thompson 2005), the contention that the boundaries of cultural variability may not be most apparent at the “national” level. Further research that examines the introduction of consumer products with gender-related attributes in “masculine” versus “feminine” cultures would be illuminating.

Trade Agreements, Harmful Products, and Acknowledging Public Health

This case study also prompts the following question for discussion: What is the morality of private profit prevailing over public health? Corresponding with trade liberalization in Japan and Korea, Philip Morris prepared a set of guidelines, for public affairs purposes, to respond to questions and criticisms the company would likely face. A Philip Morris (1989c) white paper, concerning the export of cigarettes, advised placing focus on the economic benefits while claiming that trade liberalization was not a public health matter. Pointing to the economic benefits was U.S. cigarette exports generating a multi-billion dollar trade surplus that was in stark contrast to the country’s overall trade deficit. The U.S. tobacco industry’s net trade surplus was $3.6 billion in 1988 and, according to the U.S. Commerce Department, represented one of merely six industry categories to attain a surplus greater than $1 billion (Philip Morris undated). The trade surplus for cigarettes, it was argued, benefitted the American economy and contributed to upholding several jobs, including those held by U.S. tobacco farmers. According to Philip Morris, “Trade policy, not morals or health policy, is the fundamental issue involved in the exportation of cigarettes” (1989c, p. 2500057657), an argument that was echoed by Clayton Yeutter, who served as the USTR during the mid and late 1980s and subsequent to his government role joined BAT’s Board of Directors (Brandt 2007).

Despite these trade and economic arguments put forward as well as the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) primary function being to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible,” the WTO’s Appellate Body has recognized the necessity for protecting public health when dealing with trade disputes between nations. For example, Canada filed a complaint against the European Communities regarding measures imposed by France with respect to asbestos. Canada alleged that France’s ban on the importation of asbestos and products containing asbestos was a violation of trade agreement stipulations, including the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). However, the WTO’s Appellate Body upheld the French Decree and ruled that the health risks linked with asbestos should be accounted for and acknowledged that nations have the right to put measures in place with the aim of protecting public health. Canada’s federal government has undergone considerable scrutiny for its position (e.g., Canada has also opposed chrysotile, a principal asbestos fibre, being listed as a substance governed by the Rotterdam Convention, which deals with the trade of harmful substances) and the nation’s role in being a global leader in the export of asbestos, with nations such as Indonesia, Thailand, and India being particularly important markets (Attaran and Boyd 2008; Butler et al. 1997; Randerson and James 2001).

An ongoing trade and investment dispute that shares some parallels with the asbestos example involves Philip Morris International and Uruguay. While trade disputes were traditionally contested among countries, numerous trade agreements have emerged that allow companies to sue countries or foreign governments directly (Tavernise and Sabrina 2013). Philip Morris International has sued Uruguay and argues that the country’s tobacco control regulations unfairly restrict trade and harms their investments in accordance with a bilateral investment treaty between Switzerland, where Philip Morris International is based, and Uruguay. The tobacco company’s ongoing challenge pertains to Uruguay regulations concerning the size and content of mandated pictorial health warnings on cigarette packaging and requirements for a single brand presentation (e.g., brand variants such as “Light” and “mild,” which are deemed misleading, are not allowable) (McGrady and Benn 2012). Referring to an array of international trade and investment treaties, the tobacco industry has also threatened legal action toward countries such as Namibia, Gabon, Togo, and Uganda in efforts to undermine the possible implementation of tobacco control measures. The possibilities of such legal claims are highly intimidating, given the resources of leading tobacco firms relative to many developing countries around the world. For example, the net revenue of Philip Morris International for 2012 was $77 billion, which substantially exceeds the gross domestic product of Uruguay (Tavernise and Sabrina 2013). The aforementioned developments prompted The New York Times’ Editorial Board (2013) to state, “Trade agreements and investment treaties, which govern how governments treat foreigners that invest in their countries, are meant to make it easier to do business internationally. But they should not serve as means by which corporations undermine legitimate public health regulations.”

While a focal point of our case study has been the mid and late 1980s when trade liberalization emerged in Japan and Korea for cigarettes, the general tensions underlying legitimate business and profit maximization versus public policy measures necessary to protect human health and wellbeing remain timely and topical. In recent international trade agreement negotiations between Canada and the European Union, for example, Germany expressed considerable concerns about clauses allowing foreign investors to sue governments of domestic policy that are hurtful to their investments (Chase and Steven 2014). Additionally, the USTR has seemingly broadened the set of stakeholders it represents in more recent international trade agreement negotiations, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, by offering a proposal specific to tobacco regulation and recommending a general exception for matters pertaining to the protection of public health (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2013). Whereas tobacco was once identified as a priority product for export, the USTR has reconsidered its position and now identifies tobacco, specifically, as a product where the domestic role of regulation and the need for public health measures is acknowledged.

Conclusion

Philip Morris introduced Virginia Slims cigarettes in the U.S. market in 1968 in an effort to appeal to women, who represented a considerable market opportunity. The longstanding brand image of Virginia Slims includes femininity, women’s liberation, and female empowerment, and cigarettes with “slim” and extra length product attributes are clearly characterized by American consumers as “feminine.” Made possible by the actions of the U.S. government, Philip Morris entered major Asian markets such as Japan and Korea during the mid 1980s, which was strategically opportune for the tobacco firm as total cigarette sales began to decline domestically. Philip Morris’ internal marketing planning documents, made public from litigation, reveal women were targeted in Japan, in defiance of self-regulatory codes, and “starters,” an important contributor to overall market volume, were carefully monitored in both Japan and Korea. Philip Morris’ strategic interest in “starters,” as revealed in their internal documentation, contradicts the company’s claims that their marketing activities are merely directed toward a “mature” market of existing smokers. Philip Morris embraced an adaptive marketing approach for introducing Virginia Slims to these two major Asian markets, most notably Korea, where the brand was targeted to men. This case study highlights the importance of accounting for cross-cultural dimensions, such as masculinity and femininity, and assessing their applicability to smoking behavior. This case study also provides insight about consumer perceptions of “slims” as a cigarette product descriptor. Finally, trade agreements serve important functions such as enhancing competition and economic prosperity, but should include a common exception for subject matter that is deemed necessary to protect public health. Although debate is to be expected about what does or does not constitute such subject matter, it is clear that a common exception should be applicable for inherently harmful products such as tobacco.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative Idea Grant. The authors would also like to thank Jeff Darling, Judith Mackay, Rick Pollay, and Derek Taylor for their assistance or comments on a previous draft of this research as well as three anonymous reviewers. In particular, Timothy Dewhirst thanks the Canada-U.S. Fulbright Program, as he was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of California, San Francisco during the early stages of this research. Wonkyong B. Lee acknowledges the Dancap Private Equity Faculty Research Award. Geoffrey T. Fong is supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research and a Cancer Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. Pamela M. Ling acknowledges National Cancer Institute Grant No. CA87472. Both Timothy Dewhirst and Geoffrey T. Fong have served as a paid expert witness or consulting expert for governments in countries whose policies are being challenged by parties under trade agreements.

Footnotes

Moral principles concern what behaviors or actions are regarded as right or wrong (Bartels et al. 2015). We acknowledge that “ethical” and “moral” should not be used interchangeably, but one challenge researchers face is that the concepts are often defined in highly similar ways (e.g., Ferrell et al. 1985). To differentiate the concepts, for our purposes “ethics” refers to rules, standards, and principles that generally guide what is considered to be acceptable or appropriate conduct, whereas “moral” is offered in this instance to pose the question of whether it is regarded as right or wrong for private profit to be maximized at the expense of people and their health.

The Tobacco Institute, which was established in 1958 and based in Washington, DC, served a lobbying and public relations function in the United States and represented its members, including Philip Morris, on matters of common interest pertaining to litigation, politics, and public opinion (Dewhirst 2005).

References

- Aaker DA, Fuse Y, Reynolds FD. Is life-style research limited in its usefulness to Japanese advertisers? Journal of Advertising. 1982;11(1):31–36. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SJ, Dewhirst T, Ling PM. Every document and picture tells a story: Using internal corporate document reviews, Semiotics, and content analysis to assess tobacco advertising. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(3):254–261. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong R. The relationship between culture and perception of ethical problems in international marketing. Journal of Business Ethics. 1996;15:1199–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould EJ, Thompson CJ. Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research. 2005;31(4):868–882. [Google Scholar]

- Attaran A, Boyd DR. Asbestos mortality: A Canadian export. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;179(9):871–872. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. R.J. Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball DA, McCulloch WH, Jr, Frantz PL, Geringer JM, Minor MS. International business: The challenge of global competition. 9. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels DM, Bauman CW, Cushman FA, Pizarro DA, McGraw AP. Moral judgment and decision making. In: Keren G, Wu G, editors. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making. Chichester: Wiley; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Age. 1968. Jul 29, Benson & Hedges Introduces New Cigaret [sic] For Women; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt AM. The cigarette century: The rise, fall, and deadly persistence of the product that defined America. New York: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco. R&D/Marketing Conference; 1985. Bates No. 100501581-100501657. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu/data/s/x/f/sxf34a99/sxf34a99.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Butler D, Spurgeon D. Canada and France fall out over the risks of asbestos. Nature. 1997;385:379. doi: 10.1038/385379b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes N, Balfour F. Business Week. 2009. May 4, Philip Morris unbound; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: New findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005;100(6):837–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SM. Tobacco document research reporting. Tobacco Control. 2005;14(6):368–376. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Laixuthai A. NBER Working Paper # 5543. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc; 1996. U.S. Trade Policy and Cigarette Smoking in Asia. [Google Scholar]

- Chase S. The Globe and Mail. 2014. Jul 28, Ottawa downplays German trade concerns; p. A3. [Google Scholar]

- Cho N. You’ve come a long way, mister: Virginia Slims Woos Korean Men. The Wall Street Journal. 1997 Jan 14;:B8. [Google Scholar]

- Christie PMJ, Kwon IWG, Stoeberl PA, Baumhart R. A cross-cultural comparison of ethical attitudes of business managers: India, Korea and the United States. Journal of Business Ethics. 2003;46:263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland M, Laroche M. Acculturation to the global consumer culture: Scale development and research paradigm. Journal of Business Research. 2007;60(3):249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JH, Ruhe JA. Perceptions of country corruption: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics. 2003;43:275–288. [Google Scholar]

- De Mooij M. Masculinity/femininity and consumer behavior. In: Hofstede G, editor. Masculinity and femininity: The taboo dimension of national cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- De Mooij M. Global marketing and advertising: Understanding cultural paradoxes. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst T. Public relations. In: Goodman J, editor. Tobacco in history and culture: An encyclopedia. Farmington Hills, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 2005. pp. 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst T. Tobacco Portrayals in U.S. advertising and entertainment media. In: Jamieson PE, Romer D, editors. The changing portrayal of adolescents in the media since 1950. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 250–283. [Google Scholar]

- Dollisson J. 1989 2nd Revised Forecast Presentation—corporate affairs; 1989. Jun 15, Bates No. 2500101311-2500101323. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fml19e00. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge CP. Smoking in Korea. Korea Journal. 1980;20(4):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review. 1989;14(4):532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Report to Congress Pursuant to the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act. 1967. Jun 30, Bates No. 2016002556–2016002617. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Report to Congress for 1990 Pursuant To The Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act. 1992. Bates No. 91836698–91836735. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell OC, Fraedrich J. Business ethics: Ethical decision making and cases. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell OC, Fraedrich J, Gresham LG. A contingency framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing. Journal of Marketing. 1985;49(Summer):87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman V. The Female Smoker Market. Lorillard Tobacco Company Memorandum Sent to Dick Smith. 1973 Jun 28; Bates No. 03375503-03375510. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iyh76b00.

- Gaouette N. Japan ads sell women on smoking. The Christian Science Monitor. 1998 Mar 9; http://www.csmonitor.com/1998/0309/030998.intl.intl.1.html.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]