Abstract

Does participation in one wave of a survey have an effect on respondents’ answers to questions in subsequent waves? In this article, we investigate the presence and magnitude of “panel conditioning” effects in one of the most frequently used data sets in the social sciences: the General Social Survey (GSS). Using longitudinal records from the 2006, 2008, and 2010 surveys, we find evidence that at least some GSS items suffer from this form of bias. To rule out the possibility of contamination due to selective attrition and/or unobserved heterogeneity, we strategically exploit a series of between-person comparisons across time-in-survey groups. This methodology, which can be implemented whenever researchers have access to at least three waves of rotating panel data, is described in some detail so as to facilitate future applications in data sets with similar design elements.

Sociologists have long recognized that longitudinal surveys are uniquely valuable for making causal assertions and for studying change over time. Scholars have also long been aware of the many special challenges that accompany the use of such surveys: they are more expensive to administer, they raise greater data disclosure concerns, and they suffer from additional forms of non-response bias. Nevertheless, researchers have generally been content to assume that longitudinal surveys do not suffer from the sorts of “testing” or “reactivity” biases that sometimes arise in the context of experimental or intervention-based research. The implicit assumption is that answering questions in one round of a survey in no way alters respondents’ reports in later waves. If this assumption is false, scholars risk mischaracterizing the existence, magnitude, and correlates of changes across survey waves in respondents’ attitudes and behaviors.

In this article, we investigate the presence and magnitude of “panel conditioning” effects in the General Social Survey (GSS).1 The GSS is a foundational data resource in the social sciences, surpassed by only the U.S. Census and the Current Population Survey in terms of overall use (Smith 2008). In 2006, the survey made the transition from a replicating cross-sectional design to a design that uses rotating panels. Respondents are now asked to participate in up to three waves of survey interviews, with an identical set of core items appearing in each wave. The core GSS questionnaire touches on a variety of social and political issues, including abortion, intergroup tolerance, crime and punishment, government spending, social mobility, civil liberties, religion, and women’s rights (to name just a few). Basic socio-demographic information is also collected from each respondent at the time of their interview and then re-collected in subsequent rounds.

Our primary objective is to determine whether panel conditioning influences the overall quality of these data.2 Along the way, we provide a useful methodological framework that can be used to identify panel conditioning effects in other commonly-used data sets. Simply comparing response patterns across individuals who have and have not participated in previous waves of a survey is a good first step, but more sophisticated techniques are needed to convincingly differentiate between panel conditioning and biases introduced by panel attrition (Das, Toepoel, and van Soest 2011; Warren and Halpern-Manners 2012). As we describe in more detail below, our approach (which can be implemented in any longitudinal data set that contains at least three waves of overlapping panel data) resolves this issue by strategically exploiting between-person comparisons across rotation groups.

We believe that this is an important contribution to the emerging literature on panel conditioning effects in social science surveys. Most prior research on this subject, including our own, has focused on the incidence and magnitude of panel conditioning using a narrow subset of attitudinal or behavioral measures (e.g., employment status or life satisfaction). These analyses have tended to use weaker methods to measure panel conditioning effects and have rarely considered the prevalence of the problem across topical domains. In this article, we offer a general assessment of panel conditioning in an omnibus survey that is heavily used by social scientists for a wide variety of research purposes. Our results should be valuable to users of the GSS and to researchers who are interested in identifying panel conditioning effects in other data sets that also include an overlapping panel component.

The remainder of this paper is organized into four main sections. In the section that follows, we summarize the literature on panel conditioning and provide a theoretical rationale for examining the issue within the context of the GSS. Next, we describe the methodology we use to identify panel conditioning effects. This discussion is meant to be non-technical so as to facilitate future applications in data sets with similar design elements. In the third section, we present our main findings and then subject these findings to a falsification test. Finally, we conclude by discussing the implications of our research for scholars who work with the GSS, as well as other sources of longitudinal social science data.

Panel Conditioning and the GSS

When does survey participation change respondents’ actual attitudes and behaviors? When does survey participation change merely the quality of their reports about those attitudes and behaviors? Elsewhere, we have developed seven theoretically-motivated hypotheses about the circumstances in which panel conditioning effects are most likely to occur (Warren and Halpern-Manners 2012).3 These hypotheses are grounded in theoretical perspectives on the cognitive processes that underlie attitude formation and change, decision-making, and the relationship between attitudes and behaviors (see, e.g., Feldman and Lynch 1988). In short, responding to a survey question is a cognitively and socially complex process that may or may not leave the respondent unchanged and/or equally able to provide accurate information when re-interviewed in subsequent waves. Five of these hypotheses suggest that panel conditioning effects could potentially arise within the context of the GSS.

First, respondents’ attributes may at least appear to change across waves when items (like many of those featured on the GSS) require them to provide socially non-normative or undesirable responses (Torche, Warren, Halpern-Manners, and Valenzuela 2012). The experience of answering survey questions can force respondents to confront the fact that their attitudes, behaviors, or statuses conflict with what mainstream society regards as normative or appropriate (Schaeffer 2000; Toh, Lee, and Hu 2006; Tourangeau, Rips, and Rasinski 2000).4 Some respondents may react by bringing their actual attitudes or behaviors into closer conformity with social norms. Others may simply avoid cognitive dissonance and the embarrassment associated with offering non-normative responses by bringing their answers into closer conformity with what they perceive as socially desirable.5 In both cases, the end result would be the same: researchers would observe changes over time in respondents’ attributes that would not have occurred had the initial interview not taken place.

Second, respondents’ attributes may appear to change across waves as they attempt to manipulate the survey instrument in order to minimize their burden (see, e.g., Bailar 1989). Respondents sometimes find surveys to be tedious, cognitively demanding, and/or undesirably lengthy (Krosknick 1991; Krosnick, Holbrook, Berent, Carson, Hanemann, Kopp, Mitchell, Presser, Ruud, Smith, Moody, Green, and Conaway 2002; Tourangeau, Rips, and Rasinski 2000). To get around these hassles, respondents in longitudinal studies may learn how to direct or manipulate the survey experience in such a way that minimizes the overall amount of time or energy that they have to devote to it (Duan, Alegria, Canino, McGuire, and Takeuchi 2007; Wang, Cantor, and Safir 2000).6 In the GSS, for example, a respondent may learn during their first interview that they are asked to provide many additional details about their job characteristics and work life. In order to reduce the duration of follow-up surveys, some respondents may subsequently report that they are out of the labor force or unemployed.7 The result would be the appearance of change across waves when no change has actually occurred.

Third, as hypothesized by Waterton and Lievesley (1989:324), it is possible that some respondents change their answers to survey questions as they gain an “improved understanding of the rules that govern the interview process.” When first interviewed, participants in the GSS may not have had full access to the information requested from them, may not have known how to make use of various response options, or may not have known how or when to ask clarifying questions. Upon re-interview, these individuals may be better prepared and more cognizant of “how surveys work.” While this may translate into undesirable manipulation of the survey instrument, as posited above, it may also lead to more accurate and complete responses over time. This would again result in the appearance of change over time when respondents’ underlying attributes remain the same (see, e.g., Mathiowetz and Lair 1994; Sturgis, Allum, and Brunton-Smith 2009).

Fourth, respondents may become more comfortable with and trusting of the survey experience after being exposed to the survey process and interviewers (van der Zouwen and van Tilburg 2001). Survey methodologists have found that respondents’ judgments about the relative benefits and risks associated with answering survey questions are significantly related to the chances that they provide complete and accurate answers (Dillman 2000; Krumpar 2013; Rasinski, Willis, Baldwin, Yeh, and Lee 1999; Willis, Sirken, and Nathan 1994). As respondents become more familiar with and trusting of the survey process and with interviewers and interviewing organizations, they may become less suspicious and their confidence in the confidentiality of their responses may grow. Participating in the GSS may provide evidence about the survey’s harmless nature, reduce suspicion, or increase respondents’ comfort level. Any of these effects could lead to changes in respondents’ reported attitudes or behaviors.

Finally, respondents’ answers to factual questions may change over time as they acquire more and better information about the topic at hand (Toepoel, Das, and van Soest 2009). After an initial interview, respondents may “follow-up” on unfamiliar items by consulting external sources and/or people who are knowledgeable in the area. In this scenario, prior questions serve as stimuli for obtaining the type of information that is needed to give correct responses in later waves. In many cases, it may not even be necessary that respondents remember that they encountered the item during a previous interview. As Cantor (2008:136) points out, all that matters is that “the process of answering the question the first time changes what is eventually accessible in memory the next time the question is asked.” The GSS includes a number of “knowledge tests” that may be especially prone to this form of panel conditioning.

Unfortunately, these hypotheses have not been well-validated using the sorts of data sets social scientists typically rely on. One consequence of this is that we know very little about the nature and magnitude of panel conditioning in important data resources like the GSS.8 Whereas most large-scale surveys provide users with methodological documentation about issues like sampling, attrition, and missing data, we know of none that routinely provides information about panel conditioning based on strong methods for understanding such biases. In the short run, we hope that our empirical estimates of panel conditioning in the GSS will improve the scholarship that is based on analyses of these data. In the longer run, we intend for our research design to serve as a methodological model for assessing panel conditioning in surveys like the GSS that employ rotating panel designs.9

Data and research design

The GSS is a large, full-probability survey of non-institutionalized adults in the United States. It has been administered annually (1972–1993) or biennially (1994 onward) since 1972 by NORC at the University of Chicago. In 2006, the GSS switched from a cross-sectional design to a rotating panel format. Under the new setup, subsets of about 2,000 respondents are randomly selected in each wave for re-interview two and four years later. The longitudinal panel that began the GSS in 2006 was re-interviewed in 2008 and 2010; the panel that began in 2008 was re-interviewed in 2010 and will be re-interviewed again in 2012. As described below, our focus is on responses to the 2008 survey by two groups of individuals: those who were interviewed for the first time in 2006 (or Cohort A) and those who were interviewed for the first time in 2008 (or Cohort B).

At first glance, it might seem that the easiest way to identify panel conditioning effects in these data would be to compare the responses given by individuals who were new to the survey in 2008 (Cohort B) to those given by individuals who first participated in 2006 (Cohort A). The problem with this approach is its inability to distinguish the effects of panel conditioning from the effects of panel attrition. Whereas the new rotation group may be representative of the original target population (i.e., non-institutionalized adults living in the United States at the time of the 2008 survey), the 2006 cohort may have suffered from non-random attrition between the 2006 and 2008 waves. Unless credible steps are taken to adjust for the resulting panel selectivity, differences in responses between cohorts cannot be clearly attributed to panel conditioning (Halpern-Manners and Warren 2012).

Various methodologies have been proposed to deal with this issue (see, e.g., Das, Toepoel, and van Soest 2011; Warren and Halpern-Manners 2012). One of the most common involves the use post-stratification weights (Clinton 2001; Nukulkij, Hadfield, Subias, and Lewis 2007). Under this approach, attrition is assumed to be random conditional on a pre-determined set of observable characteristics, which are then used to generate weights that correct for discrepancies between different cohorts of respondents. As others have pointed out, the overall effectiveness of this technique depends entirely on whether or not assumptions concerning “ignorability” are met (Das, Toepoel, and van Soest 2011; Sturgis, Allum, and Brunton-Smith 2009; Warren and Halpern-Manners 2012). If the two cohorts under consideration (i.e., the 2006 and 2008 cohorts) differ in ways that are not easily captured by the variables used to construct the weights, contamination due to panel attrition cannot be ruled out.

One way around this problem is to “pre-select” individuals that have the same underlying propensity to persist in the sample. Consider, for example, Cohorts A and B as defined above. These groups of respondents began the GSS in 2006 and 2008, respectively. If we systematically select individuals from both cohorts who participated in at least the first two waves of survey interviews, and then examine their responses in 2008, we can accurately identify the effects of panel conditioning in that year. Both sets of respondents experienced the same social and economic conditions at the time of their interview in 2008, and both exhibited the same propensity to persist in (or attrite from) the GSS panel (because both participated in the same number of waves).10 The key difference between the groups is that members of the 2006 cohort were experienced GSS respondents in 2008 and members of 2008 cohort were not.11

This is the approach that we use in our analysis. Using panel data from the 2006, 2008, and 2010 waves of the GSS, we were able to identify 3,117 respondents who completed at least the first two rounds of survey interviews.12 Of these respondents, 1,536 entered the sample in 2006 (the 2006 cohort) and 1,581 entered the sample in 2008 (the 2008 cohort). If the responses given by individuals in the first group are significantly different than the responses given (in the same year) by individuals in the second, we can infer that these differences came about from panel conditioning. No adjustments for panel attrition are necessary and person weights are not needed to correct for sub-sampling and/or non-response.13 By design, the 2006 and 2008 cohorts have already been equated on both observed and unobserved characteristics.14

As noted above, items on the GSS span a wide variety of substantive topics (Smith, Kim, Koch, and Park 2007). Although theory suggests that some of these topics may be more or less prone to panel conditioning effects, we feel it is important (for the sake of completeness) to examine every instance in which such biases could possibly occur. For this reason, we considered all 2008 GSS variables that met two very basic requirements: (1) the item had to be answered by the respondent and not the survey interviewer; and (2) the variable in question had to be empirically distinct from other measures in our analysis. The first rule meant that items like “date of interview” and “sex of interviewer” were excluded from the study. The second rule meant that we considered variables like “age” and “year of birth,” but not both.15

After eliminating items that did not satisfy these criteria, we were left with a total of 310 variables. To analyze panel conditioning effects in each of these measures, we carried out hypothesis tests comparing the response patterns in 2008 across cohorts. For continuous measures we used t-tests to compare group means; for categorical measures we used chi-square tests (if all cell sizes were in excess of 5) and Fisher’s exact tests (if they were not).16 Because the GSS employs a split-ballot design, where certain items are only asked of certain individuals in a given year, members of the 2006 cohort did not necessarily receive the “treatment” for all variables in our sample.17 Such cases were removed from the analysis using pairwise deletion. See Appendix Table A1 for complete information on all measures, including sample sizes disaggregated by treatment status.

Table A1.

Sample sizes and test statistics for all items (n = 310)

| Sample sizes | Difference between cohorts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mnemonic | 2006 | 2008 | chi2/t | df | p | Adjusted p |

| Abortion is acceptable for any reason | abany | 1,024 | 1,034 | 1.75 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Is abortion okay if chance of serious defect? | abdefect | 1,009 | 1,020 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Is abortion okay if woman's health is in jeopardy? | abhlth | 1,021 | 1,025 | 0.21 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

| Is abortion okay if woman does not want more kids? | abnomore | 1,022 | 1,034 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.77 |

| Abortion is acceptable for financial reasons | abpoor | 1,024 | 1,036 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Abortion is acceptable in event of rape | abrape | 1,002 | 1,024 | 0.37 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Abortion is okay if the woman is not married | absingle | 1,023 | 1,041 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.58 | 0.86 |

| Number of household members ages 18+ | adults | 1,515 | 1,578 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Sci. research should be supported by public dollars | advfront | 475 | 1,119 | 1.07 | 3 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Opinion of affirmative action | affrmact | 959 | 974 | 1.64 | 3 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

| Age | age | 1,514 | 1,571 | 3.08 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Age when first child was born | agekdbrn | 1,106 | 1,146 | −0.31 | 0.76 | 0.90 | |

| Ever read horoscope or astrology report | astrolgy | 492 | 1,163 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.57 | 0.86 |

| Believes astrology is scientific | astrosci | 474 | 1,123 | 2.88 | 2 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Frequency of attendance at religious services | attend | 1,533 | 1,574 | 9.59 | 8 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Number of household members ages 0–5 | babies | 1,515 | 1,560 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.76 | |

| Feelings about the bible | bible | 1,520 | 1,553 | 4.73 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Believes the universe began with a huge explosion | bigbang | 358 | 846 | 3.17 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Agrees right and wrong is not black and white | blkwhite | 1,511 | 1,535 | 3.59 | 3 | 0.31 | 0.72 |

| Nativity | born | 1,535 | 1,581 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Believes father's gene determines sex of child | boyorgrl | 219 | 850 | 3.45 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| Favor or oppose the death penalty for murder | cappun | 1,452 | 1,496 | 0.51 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.81 |

| Number of children | childs | 1,535 | 1,580 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 0.75 | |

| Ideal number of children | chldidel | 979 | 998 | −1.32 | 0.19 | 0.61 | |

| Subjective class identification | class | 1,531 | 1,567 | 2.01 | 3 | 0.57 | 0.86 |

| How close the respondent feels to African Americans | closeblk | 1,038 | 1,060 | 9.87 | 8 | 0.27 | 0.71 |

| How close the respondent feels to whites | closewht | 1,040 | 1,060 | 11.56 | 8 | 0.17 | 0.59 |

| Believes anti-religionists should be allowed to teach | colath | 1,010 | 1,050 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| Believes communist teachers should be fired | colcom | 993 | 1,024 | 2.03 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.56 |

| Highest college degree | coldeg1 | 178 | 423 | 14.77 | 7 | 0.04 | 0.34 |

| Believes homosexuals should be allowed to teach | colhomo | 1,021 | 1,055 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.44 | 0.79 |

| Believes militarists should be allowed to teach | colmil | 1,007 | 1,038 | 4.39 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.34 |

| Believes racists should be allowed to teach | colrac | 1,010 | 1,045 | 3.33 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Ever taken any college-level science course | colsci | 488 | 1,160 | 8.71 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Number of college-level science courses | colscinm | 185 | 429 | 1.11 | 0.27 | 0.70 | |

| Respondents understanding of questions | comprend | 1,533 | 1,581 | 2.94 | 2 | 0.23 | 0.67 |

| Confidence in military | conarmy | 1,015 | 1,044 | 5.21 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Confidence in major companies | conbus | 1,002 | 1,039 | 1.54 | 2 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Confidence in organized religion | conclerg | 1,003 | 1,039 | 3.41 | 2 | 0.18 | 0.61 |

| Believes the continents have been moving | condrift | 439 | 1,024 | 5.15 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.25 |

| Confidence in education | coneduc | 1,023 | 1,050 | 1.89 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Confidence in executive branch | confed | 1,006 | 1,034 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Confidence in financial institutions | confinan | 1,014 | 1,047 | 2.51 | 2 | 0.28 | 0.71 |

| Confidence in supreme court | conjudge | 1,006 | 1,031 | 2.47 | 2 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Confidence in organized labor | conlabor | 974 | 1,012 | 2.29 | 2 | 0.32 | 0.72 |

| Confidence in congress | conlegis | 1,005 | 1,039 | 1.91 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Confidence in medicine | conmedic | 1,017 | 1,054 | 0.80 | 2 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Confidence in press | conpress | 1,015 | 1,046 | 0.59 | 2 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Confidence in scientific community | consci | 974 | 1,014 | 1.99 | 2 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| Participation/recording consent | consent | 1,536 | 1,579 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Confidence in television | contv | 1,016 | 1,047 | 1.23 | 2 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Feelings about courts' treatment of criminals | courts | 1,430 | 1,466 | 0.71 | 2 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| Highest degree | degree | 1,535 | 1,581 | 3.32 | 4 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

| Specific denomination | denom | 761 | 873 | 6.08 | 6 | 0.41 | 0.77 |

| Denomination in which the respondent was raised | denom16 | 799 | 883 | 50.48 | 26 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Believes whites are hurt by affirmative action | discaff | 1,004 | 1,038 | 0.01 | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Equally/less qualified women get jobs instead of men? | discaffm | 494 | 481 | 4.20 | 3 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Equally/less qualified men get jobs instead of women? | discaffw | 483 | 529 | 2.09 | 3 | 0.55 | 0.84 |

| Believes divorce should be easier or more difficult | divlaw | 955 | 986 | 0.65 | 2 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Ever been divorced or separated | divorce | 831 | 883 | 0.54 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Own or rent dwelling | dwelown | 1,003 | 1,024 | 0.23 | 2 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| How many in family earned income | earnrs | 1,532 | 1,580 | −0.15 | 0.88 | 0.94 | |

| Believes the earth goes around the sun | earthsun | 460 | 1,081 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Years of education | educ | 1,533 | 1,579 | 1.56 | 0.12 | 0.50 | |

| Believes electrons are smaller than atoms | electron | 388 | 890 | 3.80 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.41 |

| Believes govt. should reduce income inequality | eqwlth | 1,011 | 1,048 | 7.26 | 6 | 0.30 | 0.71 |

| Believes human beings developed from animals | evolved | 438 | 1,028 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| Ever worked as long as one year | evwork | 452 | 518 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Familiar with experimental design | expdesgn | 466 | 1,095 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Knows why experimental design is preferred | exptext | 459 | 1,068 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Believes people are fair or take advantage of others | fair | 1,019 | 1,056 | 3.16 | 2 | 0.21 | 0.63 |

| Reason not living with parents when 16 | famdif16 | 403 | 502 | 4.93 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.68 |

| Number of family generations in household | famgen | 1,536 | 1,581 | 17.70 | 6 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Living with parents when 16 | family16 | 1,534 | 1,581 | 5.36 | 8 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Afraid to walk at night in neighborhood | fear | 1,038 | 1,075 | 0.44 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

| Believes mother working does/does not hurt children | fechld | 994 | 1,019 | 14.49 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Better for men to work and women to tend home? | fefam | 995 | 1,011 | 0.62 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Make special effort to hire/promote women? | fehire | 494 | 532 | 1.79 | 4 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| For or against preferential hiring of women | fejobaff | 491 | 464 | 2.33 | 3 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

| Are women suited for politics? | fepol | 946 | 974 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.92 |

| Do preschool kids suffer if mother works? | fepresch | 989 | 1,010 | 1.04 | 3 | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| Change in financial situation in last few years | finalter | 1,532 | 1,576 | 1.50 | 2 | 0.47 | 0.81 |

| Opinion of family income | finrela | 1,517 | 1,566 | 6.96 | 4 | 0.14 | 0.53 |

| How fundamentalist is the respondent? | fund | 1,402 | 1,515 | 3.95 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.53 |

| How fundamentalist was the respondent at age 16? | fund16 | 1,476 | 1,525 | 1.31 | 2 | 0.52 | 0.84 |

| Opinion of how people get ahead | getahead | 1,042 | 1,069 | 0.95 | 2 | 0.62 | 0.89 |

| Confidence in the existence of god | god | 1,529 | 1,567 | 3.79 | 5 | 0.58 | 0.86 |

| Standard of living will improve | goodlife | 1,021 | 1,053 | 8.60 | 4 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Number of grandparents born outside the U.S. | granborn | 1,418 | 1,498 | 3.16 | 4 | 0.53 | 0.84 |

| Opinion of marijuana legalization | grass | 944 | 969 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.76 |

| Opinion of gun permits | gunlaw | 1,034 | 1,063 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| Happiness of marriage | hapmar | 692 | 760 | 3.16 | 2 | 0.21 | 0.63 |

| General happiness | happy | 1,525 | 1,576 | 4.42 | 2 | 0.11 | 0.50 |

| Condition of health | health | 1,043 | 1,076 | 0.67 | 3 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Opinion of government aid for African Americans | helpblk | 989 | 1,016 | 1.07 | 4 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Are people helpful or selfish? | helpful | 1,019 | 1,059 | 3.69 | 2 | 0.16 | 0.57 |

| Should government do more or less? | helpnot | 983 | 1,018 | 6.81 | 4 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| How important is it for kids to learn to help others? | helpoth | 517 | 1,051 | 1.84 | 4 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| Should government improve standard of living? | helppoor | 1,001 | 1,035 | 2.74 | 4 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| Should government help pay for medical care? | helpsick | 1,001 | 1,031 | 4.76 | 4 | 0.31 | 0.72 |

| Is the respondent Hispanic? | hispanic | 1,533 | 1,578 | 21.83 | 19 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| Attitude toward homosexual relations | homosex | 998 | 1,011 | 4.72 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Believes the center of the earth is very hot | hotcore | 434 | 1,028 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Number of hours worked last week | hrs1 | 749 | 952 | 2.59 | 0.01 | 0.13 | |

| Ever took a high school biology course | hsbio | 467 | 1,111 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Ever took a high school chemistry course | hschem | 469 | 1,111 | 2.64 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Highest level of math completed in high school | hsmath | 454 | 1,092 | 13.38 | 9 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| Ever took a high school physics course | hsphys | 465 | 1,109 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| Does the respondent or their spouse hunt? | hunt | 1,043 | 1,075 | 3.05 | 3 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| Who would respondent have voted for in 2004? | if04who | 328 | 482 | 0.91 | 2 | 0.63 | 0.90 |

| Family income when age 16 | incom16 | 1,513 | 1,561 | 3.12 | 4 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Total family income | income06 | 1,488 | 1,529 | 35.57 | 25 | 0.08 | 0.45 |

| Rating of African Americans' intelligence | intlblks | 980 | 993 | 5.44 | 6 | 0.49 | 0.82 |

| Rating of whites' intelligence | intlwhts | 980 | 993 | 3.31 | 6 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Internet access at home | intrhome | 488 | 1,158 | 1.34 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.68 |

| Could respondent find equally good job? | jobfind | 507 | 651 | 5.40 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Likelihood of losing job | joblose | 510 | 658 | 0.39 | 3 | 0.94 | 0.96 |

| Standard of living compared to children's | kidssol | 994 | 1,030 | 5.30 | 5 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| Believes lasers work by focusing sound waves | lasers | 362 | 857 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Allow incurable patients to die | letdie1 | 971 | 467 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Beliefs about immigration | letin1 | 975 | 1,007 | 1.53 | 4 | 0.82 | 0.93 |

| Allow anti-religionist's book in the library? | libath | 1,025 | 1,051 | 2.83 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Allow communist's book in library? | libcom | 1,015 | 1,045 | 2.18 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.53 |

| Allow homosexual's book in library? | libhomo | 1,022 | 1,058 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.94 |

| Allow militarist's book in library? | libmil | 1,018 | 1,048 | 3.07 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.45 |

| Allow racist's book in library? | librac | 1,023 | 1,051 | 2.09 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| Is life exciting or dull? | life | 1,035 | 1,065 | 0.87 | 2 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

| Would live in area where half of neighbors are black? | liveblks | 995 | 1,018 | 4.77 | 4 | 0.31 | 0.72 |

| Would live in area where half of neighbors are white? | livewhts | 994 | 1,015 | 2.09 | 4 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Number of employees at work site | localnum | 780 | 979 | 3.90 | 6 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Mother's years of schooling | maeduc | 1,340 | 1,398 | −0.83 | 0.40 | 0.77 | |

| College major | majorcol | 193 | 422 | 9.41 | 5 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Feelings about relative marrying an Asian | marasian | 995 | 1,021 | 5.83 | 4 | 0.21 | 0.64 |

| Feelings about relative marrying an African American | marblk | 998 | 1,021 | 3.59 | 4 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Feelings about relative marrying a Hispanic | marhisp | 996 | 1,021 | 4.43 | 4 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| Should homosexuals have the right to marry? | marhomo | 1,033 | 1,065 | 4.33 | 4 | 0.36 | 0.76 |

| Marital status | marital | 1,534 | 1,577 | 18.24 | 4 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Feelings about relative marrying a white person | marwht | 998 | 1,023 | 2.28 | 0.68 | 0.90 | |

| Mother's socioeconomic index | masei | 817 | 1,017 | 1.23 | 0.22 | 0.65 | |

| Mother's employment when respondent was 16 | mawrkgrw | 1,428 | 1,501 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| Mother self-employed or worked for somebody else | mawrkslf | 872 | 1,033 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| Men hurt family when they focus too much on work | meovrwrk | 999 | 1,019 | 7.15 | 4 | 0.13 | 0.51 |

| Geographic mobility since age 16 | mobile16 | 1,536 | 1,581 | 3.22 | 2 | 0.20 | 0.63 |

| Believes nanotechnology manipulates small objects | nanoknw1 | 156 | 411 | 1.49 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| Believes nanoscale materials are different | nanoknw2 | 120 | 326 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.74 | 0.90 |

| Familiarity with nanotechnology | nanotech | 474 | 1,132 | 4.72 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Costs and benefits of nanotechnology | nanowill | 305 | 701 | 4.78 | 2 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Amount spent on foreign aid | nataid | 746 | 720 | 1.37 | 2 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

| Amount spent on foreign aid (version y) | nataidy | 750 | 782 | 0.84 | 2 | 0.66 | 0.90 |

| Amount spent on national defense | natarms | 758 | 742 | 2.17 | 2 | 0.34 | 0.75 |

| Amount spent on national defense (version y) | natarmsy | 741 | 779 | 2.44 | 2 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Amount spent on assistance for childcare | natchld | 1,445 | 1,464 | 3.97 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.53 |

| Amount spent on assistance to big cities | natcity | 699 | 687 | 5.84 | 2 | 0.05 | 0.42 |

| Amount spent on assistance to big cities (version y) | natcityy | 681 | 697 | 2.24 | 2 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Amount spent on drug rehabilitation | natdrug | 754 | 735 | 9.42 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Amount spent on drug rehabilitation (version y) | natdrugy | 711 | 759 | 2.15 | 2 | 0.34 | 0.75 |

| Amount spent on education | nateduc | 767 | 761 | 2.73 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| Amount spent on education (version y) | nateducy | 754 | 800 | 0.90 | 2 | 0.64 | 0.90 |

| Amount spent on environmental protection | natenvir | 755 | 754 | 0.69 | 2 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Amount spent on environmental protection (version y) | natenviy | 746 | 786 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Amount spent on welfare | natfare | 747 | 734 | 2.07 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.76 |

| Amount spent on welfare (version y) | natfarey | 750 | 795 | 1.03 | 2 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| Amount spent on health | natheal | 769 | 749 | 0.52 | 2 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Amount spent on health (version y) | nathealy | 754 | 795 | 0.16 | 2 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| Amount spent on transportation | natmass | 1,465 | 1,477 | 4.22 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.50 |

| Amount spent on parks and recreation | natpark | 1,504 | 1,554 | 1.74 | 2 | 0.42 | 0.78 |

| Amount spent on assistance to blacks | natrace | 695 | 676 | 1.69 | 2 | 0.43 | 0.79 |

| Amount spent on assistance to blacks (version y) | natracey | 669 | 711 | 15.14 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Amount spent on highways and bridges | natroad | 1,506 | 1,537 | 1.79 | 2 | 0.41 | 0.77 |

| Amount spent on scientific research | natsci | 1,444 | 1,475 | 0.66 | 2 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| Amount spent on social security | natsoc | 1,483 | 1,511 | 1.77 | 2 | 0.41 | 0.77 |

| Amount spent on space exploration | natspac | 730 | 724 | 1.21 | 2 | 0.55 | 0.84 |

| How often does the respondent read the newspaper? | news | 1,003 | 1,026 | 1.93 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Main source of information about events in the news | newsfrom | 492 | 1,162 | 3.38 | 9 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Does science give opportunities to future generations? | nextgen | 480 | 1,134 | 1.49 | 3 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| How important is it for children to obey parents? | obey | 517 | 1,051 | 3.10 | 4 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Test of knowledge about probability | odds1 | 457 | 1,085 | 1.24 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| Test of knowledge about probability | odds2 | 457 | 1,089 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Gun in home | owngun | 1,038 | 1,074 | 0.79 | 2 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Father's years of education | paeduc | 1,116 | 1,165 | −1.00 | 0.32 | 0.72 | |

| Were parents born in U.S.? | parborn | 1,530 | 1,577 | 3.30 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| Standard of living compared to parents | parsol | 1,012 | 1,042 | 21.25 | 4 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Part- or full-time work | partfull | 969 | 1,159 | 9.94 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Father's socioeconomic index | pasei | 1,112 | 1,223 | −0.22 | 0.83 | 0.93 | |

| Father self-employed? | pawrkslf | 1,205 | 1,283 | 1.88 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.59 |

| Agrees that morality is a personal matter | permoral | 1,494 | 1,538 | 7.10 | 3 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Telephone in household | phone | 1,536 | 1,577 | 157.30 | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Is birth control okay for teenagers between 14–16? | pillok | 983 | 482 | 6.29 | 3 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Pistol or revolver in home | pistol | 1,036 | 932 | 1.23 | 2 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Okay for police to hit citizen who said vulgar things? | polabuse | 1,003 | 1,022 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| Okay for police to hit citizen who is attacking them? | polattak | 1,017 | 1,047 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.75 |

| Okay for police to hit citizen if trying to escape? | polescap | 979 | 1,021 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Ever approve of police striking citizen | polhitok | 982 | 484 | 0.10 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Okay for police to hit murder suspect? | polmurdr | 990 | 1,033 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| Think of self as liberal or conservative? | polviews | 1,493 | 1,520 | 4.96 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.84 |

| Is pope infallible on maters of faith or morals? | popespks | 335 | 167 | 4.46 | 4 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| How important is it for a child to be popular? | popular | 517 | 1,051 | 8.54 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| Feelings about pornography laws | pornlaw | 1,022 | 1,055 | 4.74 | 2 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Belief in life after death | postlife | 1,377 | 1,395 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| How often does the respondent pray? | pray | 1,527 | 1,564 | 9.58 | 5 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Should bible prayer be allowed in public schools? | prayer | 959 | 989 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.77 |

| Feelings about sex before marriage | premarsx | 973 | 1,005 | 12.52 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Which candidate did the respondent vote for in 2004? | pres04 | 954 | 976 | 11.42 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Number of household members ages 6–12 | preteen | 1,515 | 1,560 | 2.44 | 0.01 | 0.19 | |

| Agrees that sinners must be punished? | punsin | 1,441 | 1,474 | 0.32 | 3 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Thinks blacks' disadvant. are due to discrimination? | racdif1 | 959 | 990 | 2.37 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.51 |

| Thinks blacks' disadvant. are due to disabilities? | racdif2 | 980 | 1,008 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Thinks blacks' disadvant. are due to lack of education? | racdif3 | 979 | 998 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.44 | 0.79 |

| Thinks blacks' disadvant. are due to lack of will? | racdif4 | 955 | 987 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Race | race | 1,536 | 1,581 | 0.53 | 2 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Any African Americans living in neighborhood? | raclive | 1,470 | 1,528 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Feelings about open housing laws | racopen | 1,038 | 1,066 | 1.89 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Racial makeup of workplace | racwork | 534 | 637 | 7.29 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.50 |

| Believes all radioactivity is man-made | radioact | 434 | 1,034 | 5.77 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Ever had a "born again" experience? | reborn | 1,517 | 1,557 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Region of residence at age 16 | reg16 | 1,536 | 1,581 | 4.33 | 9 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| Participates frequently in religious activities? | relactiv | 1,530 | 1,568 | 16.99 | 9 | 0.05 | 0.41 |

| Has a religious experience changed life? | relexp | 1,526 | 1,567 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Turning point in life for religion | relexper | 1,524 | 1,566 | 2.40 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.50 |

| Religious preference | relig | 1,534 | 1,574 | 3.60 | 4 | 0.46 | 0.81 |

| Religion in which respondent was raised | relig16 | 1,531 | 1,570 | 9.43 | 11 | 0.58 | 0.86 |

| Strength of religious affiliation | reliten | 1,421 | 1,465 | 1.12 | 3 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Try to carry religious beliefs into other dealings | rellife | 1,511 | 1,555 | 1.28 | 3 | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Any turning point when less committed to religion? | relneg | 754 | 1,570 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Does respondent consider self a religious person? | relpersn | 1,518 | 1,563 | 2.63 | 3 | 0.45 | 0.81 |

| Type of community when 16 | res16 | 1,534 | 1,580 | 1.80 | 5 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Continue to work if became rich? | richwork | 582 | 704 | 5.73 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Rifle in home | rifle | 1,036 | 925 | 2.57 | 2 | 0.28 | 0.71 |

| Respondent's income | rincom06 | 831 | 1,009 | 47.49 | 25 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Agrees that immoral people corrupt society | rotapple | 1,509 | 1,537 | 3.99 | 3 | 0.26 | 0.69 |

| Does the gun in the house belong to the respondent? | rowngun | 333 | 382 | 0.78 | 2 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Relationship to head of household | rplace | 1,535 | 1,578 | 26.24 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Is the respondent a visitor in the household? | rvisitor | 1,536 | 1,581 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.90 |

| Satisfaction with financial situation | satfin | 1,532 | 1,576 | 4.84 | 2 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Job satisfaction | satjob | 1,054 | 1,207 | 3.72 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Ever tried to convince others to accept Jesus? | savesoul | 1,530 | 1,573 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| Do the benefits of scientific research outweigh the costs? | scibnfts | 452 | 1,084 | 4.51 | 2 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Main source of info about science and technology | scifrom | 488 | 1,152 | 7.30 | 9 | 0.61 | 0.87 |

| Has a clear understanding of scientific study? | scistudy | 485 | 1,148 | 4.95 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.46 |

| What it means to study something scientifically | scitext | 334 | 844 | 17.83 | 5 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Likely source of information about scientific issues | seeksci | 489 | 1,142 | 4.72 | 7 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Socioeconomic index | sei | 1,386 | 1,497 | 2.28 | 0.02 | 0.25 | |

| Feelings about sex education in public schools | sexeduc | 990 | 1,010 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| Shotgun in home | shotgun | 1,036 | 926 | 3.48 | 2 | 0.18 | 0.60 |

| Number of siblings | sibs | 1,534 | 1,579 | −0.24 | 0.81 | 0.92 | |

| Frequently spend an evening at a bar? | socbar | 1,002 | 1,026 | 4.94 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.84 |

| Frequently spend evenings with friends? | socfrend | 1,001 | 1,024 | 11.55 | 6 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Frequently spend evenings with neighbors? | socommun | 999 | 1,025 | 7.37 | 6 | 0.29 | 0.71 |

| Frequently spend evenings with relatives? | socrel | 1,003 | 1,026 | 2.54 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| How long does it take earth to travel around the sun? | solarrev | 308 | 803 | 1.24 | 2 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Favor spanking to discipline children? | spanking | 996 | 1,012 | 0.23 | 3 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Spouse's religious denomination | spden | 342 | 431 | 26.34 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Spouse's years of education | speduc | 692 | 757 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.83 | |

| Has spouse ever worked as long as a year? | spevwork | 166 | 226 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| How fundamentalist is spouse currently? | spfund | 660 | 727 | 4.51 | 2 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Hours spouse worked last week | sphrs1 | 413 | 502 | 1.53 | 0.13 | 0.51 | |

| Should anti-religionists be allowed to speak publicly? | spkath | 1,039 | 1,068 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.81 |

| Should communists be allowed to speak publicly? | spkcom | 1,020 | 1,051 | 4.14 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.37 |

| Should homosexuals be allowed to speak publicly? | spkhomo | 1,028 | 1,059 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Should militarists be allowed to speak publicly? | spkmil | 1,022 | 1,057 | 2.93 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Should racists be allowed to speak publicly? | spkrac | 1,036 | 1,059 | 8.93 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Spouses religious preference | sprel | 695 | 758 | 11.94 | 11 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| Does respondent consider self a spirtual person? | sprtprsn | 1,512 | 1,558 | 2.16 | 3 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Spouse's socioeconomic index | spsei | 609 | 710 | 0.86 | 0.39 | 0.76 | |

| Is spouse self-employed? | spwrkslf | 641 | 732 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.79 |

| Spouse's labor force status? | spwrksta | 693 | 759 | 2.40 | 7 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| Is suicide okay if disease is incurable? | suicide1 | 967 | 994 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| Is suicide okay if person is bankrupt? | suicide2 | 994 | 1,010 | 3.86 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.41 |

| Is suicide okay if person dishonored their family? | suicide3 | 989 | 1,012 | 1.39 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Is suicide okay if person is tired of living? | suicide4 | 980 | 997 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.87 |

| Federal income tax | tax | 1,016 | 1,044 | 1.61 | 2 | 0.45 | 0.80 |

| Number of household members ages 13–17 | teens | 1,515 | 1,559 | 0.87 | 0.38 | 0.76 | |

| Is sex before marriage okay for people ages of 14–16? | teensex | 996 | 1,019 | 1.28 | 3 | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| How important is it for kids to think for themselves? | thnkself | 517 | 1,051 | 8.76 | 4 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| Does science make our way of life change too fast? | toofast | 478 | 1,134 | 7.82 | 3 | 0.05 | 0.41 |

| Can people be trusted? | trust | 1,021 | 1,060 | 4.30 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.50 |

| Hours per day watching television | tvhours | 1,001 | 1,023 | −1.39 | 0.17 | 0.58 | |

| Ever unemployed in last ten years? | unemp | 1,024 | 1,060 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| Union membership | union | 1,022 | 1,055 | 0.23 | 3 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Number in household who are unrelated | unrelat | 946 | 1,083 | −0.76 | 0.44 | 0.80 | |

| Expect another world war in the next 10 years? | uswary | 944 | 970 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Believes antibiotics kill viruses as well as bacteria | viruses | 454 | 1,075 | 5.32 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.24 |

| Number of visitors in household | visitors | 1,536 | 1,581 | 4.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Did the respondent vote in the 2004 election? | vote04 | 1,501 | 1,541 | 19.21 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Weeks worked last year | weekswrk | 1,525 | 1,568 | −2.10 | 0.04 | 0.34 | |

| Presence of children under six | whoelse1 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.81 |

| Presence of older children | whoelse2 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.81 |

| Presence of other relatives | whoelse3 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 3.65 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.43 |

| Presence of other relatives | whoelse4 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 0.35 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.84 |

| Presence of other adults | whoelse5 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| No one else present | whoelse6 | 1,533 | 1,581 | 4.72 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.31 |

| Ever been widowed | widowed | 1,012 | 1,033 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.96 |

| Does respondent or spouse have supervisor | wksub | 964 | 1,132 | 1.36 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Does supervisor have supervisor | wksubs | 691 | 914 | 8.05 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Does respondent or spouse supervise anyone | wksup | 961 | 1,133 | 1.53 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| Does subordinate supervise anyone | wksups | 267 | 421 | 4.28 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| Rating of blacks on wealth scale | wlthblks | 985 | 1,002 | 9.93 | 6 | 0.11 | 0.50 |

| Rating of whites on wealth scale | wlthwhts | 985 | 1,004 | 5.15 | 6 | 0.53 | 0.84 |

| Wordsum score | wordsum | 744 | 900 | 1.63 | 0.10 | 0.48 | |

| Rating of blacks on laziness scale | workblks | 985 | 989 | 6.70 | 6 | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| How important is it for a child to work hard? | workhard | 517 | 1,051 | 6.11 | 4 | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Rating of whites on laziness scale | workwhts | 988 | 993 | 7.94 | 6 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Government or private employee | wrkgovt | 1,430 | 1,503 | 1.61 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.63 |

| Self-employed or works for somebody else | wrkslf | 1,446 | 1,534 | 0.17 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Labor force status | wrkstat | 1,535 | 1,580 | 13.41 | 7 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| Believes blacks can overcome prejudice without help | wrkwayup | 989 | 1,014 | 0.99 | 4 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| Had sex with person other than spouse | xmarsex | 1,037 | 1,056 | 1.81 | 3 | 0.61 | 0.88 |

| Seen x-rated movie in last year | xmovie | 1,024 | 1,054 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.72 |

| Astrological sign | zodiac | 1,510 | 1,536 | 7.60 | 11 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

Note: The adjusted p is the p -value adjusted for the False Discovery Rate. Bolded p -values are significant at the .05 level. Degrees of freedom for chi-squared tests are given in the column labeled df. Sample sizes for each cohort are given in the column labeled sample sizes. See text for additional details.

Results

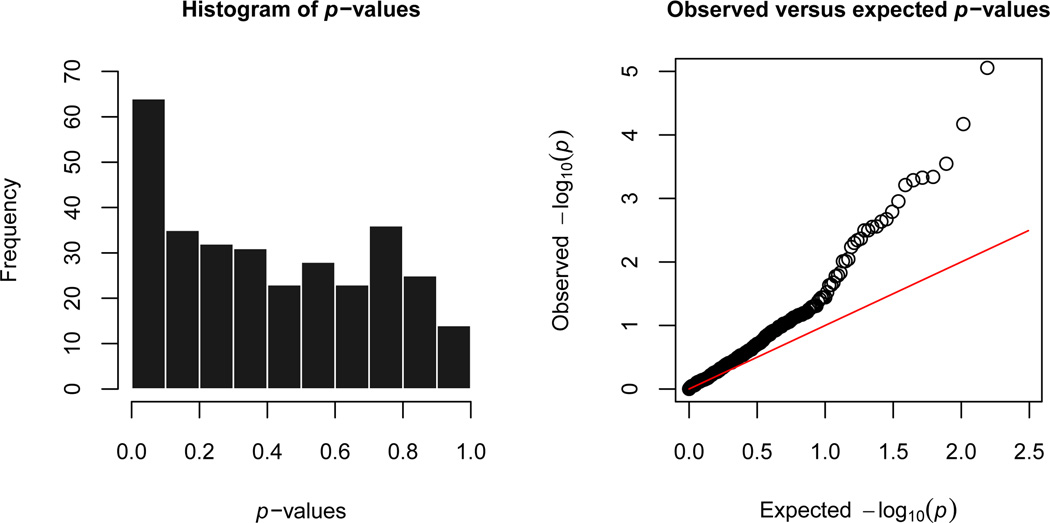

Our analysis includes significance tests for 310 different items; this makes it extremely susceptible to multiple comparison problems. Even if the null hypothesis (of no panel conditioning) is true for every item in our data set, the probability of finding at least one statistically significant effect just by chance is 1 – (1 – 0.05)310 ≈ 1, assuming a standard α-level of 0.05. To address this issue, we examined the distribution of test statistics across all items in our sample. Under the null, the p-values obtained from our tests should be uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 (Casella and Berger 2001). Approximately 5% of the test statistics should be below 0.05, another 5% should fall between 0.05 and 0.09, and so on throughout the entire [0, 1] interval. Depending on where they occur in the distribution, departures from this pattern could indicate an over-abundance of significant results.

Figure 1 gives a visual summary of the main findings. In the panel on the left, we provide a simple histogram of the p-values we obtained from our comparisons of the 2006 and 2008 cohorts. In the panel on the right, we provide a quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot comparing the empirical distribution of these values (as indicated by the black circles) to a theoretical null distribution (as indicated by the red line).18 In both instances, there is clear clustering of estimates in the extreme low end of the distribution.19 Overall, 63 of the 310 tests that we conducted were significant at a 0.10 level (whereas 31 would be expected by chance); 37 were significant at a 0.05 level (whereas 16 would be expected by chance); and 22 were significant at a 0.01 level (whereas 3 would be expected by chance). We take this as evidence that panel conditioning exists in the GSS among certain subsets of items.

Figure 1.

Histogram and Q-Q plot of observed p-values. the panel on the left shows the observed distribution of p-values for all items in our sample (n = 310). Under the null, the values should be uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. the panel on the right compares the observed distribution to a theoretical (null) distribution. If p-values are more significant than expected, points will move up and away from the red line. If p-values are uniformly distributed, the circles will track closely with the red line throughout the entire range. See text for further details.

In order to confirm this interpretation, we calculated p-values that have been adjusted for the False Discovery Rate (FDR) using the algorithm of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Many techniques exist for dealing with multiple comparison problems and there is some debate over which is the most appropriate (Gelman, Hill, and Yajmia 2012). The FDR is generally thought to be more powerful than Bonferroni-style procedures, and is frequently used when the volume of tests is high. Instead of controlling for the chances of making even a single Type 1 error, the FDR controls for the expected proportion of Type 1 errors among all significant results. In total, the FDR-adjusted estimates include 8 significant results at the p < 0.05 level and 19 significant results at the p < 0.10 level (see Appendix Table A1). If we set the FDR threshold to 5%, we can say with confidence that only 1 of these “discoveries” occurred by chance.

The direction and magnitude of panel conditioning effects

These results suggest that some people may respond differently to GSS questions depending on whether or not they have previously participated in the survey. Although this is an important finding in its own right, users of these data should also be interested in knowing which variables are subject to panel conditioning, in what direction the observed effects operate, and how big they are from a substantive standpoint. In this section, we describe the direction and magnitude of panel conditioning biases in the 2008 survey and provide some preliminary thoughts about possible mechanisms. To be appropriately conservative when interpreting the results for individual variables, we focus on items that (with a few exceptions) produced FDR-adjusted p-values < 0.10. The exceptions to this rule are noted in the text below.

First, members of the 2006 and 2008 cohorts sometimes differed in their responses to attitudinal questions about “hot-button” issues. Examples include items dealing with pre-marital sex (premarsx), first amendment rights and racism (spkrac), and governmental aid to minorities (natracey). As indicated in Table 1, members of the 2006 cohort were 14% more likely to say that sex before marriage is always or almost always wrong; 10% more likely to say that people have a right to make hateful speeches in public; and 23% more likely to say that current levels of assistance for African Americans are neither too high nor too low. These effect sizes are generally in line with estimates that have been produced in past panel conditioning research (see, e.g., Torche et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Size and direction of estimated effects in 2008, illustrative results

| Estimate (% or mean) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description of response options/measure | 2006 cohort | 2008 cohort |

| phone | Respondent refuses to give information about their phone | 1.17 | 7.93 |

| visitors | Average number of visitors in the household | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| parsol | Respondent’s standard of living is higher than their parents’ standard of living | 66.21 | 59.50 |

| rplace | The respondent is the householder or their spouse | 91.70 | 88.21 |

| adults | Average number of adults in the household | 1.97 | 1.87 |

| natracey | Respondent thinks current levels of public assistance for blacks are about right | 53.51 | 43.60 |

| marital | Respondent is divorced or widowed | 25.88 | 21.56 |

| spkrac | Respondent agrees that people have a right to make hateful speeches in public | 67.08 | 60.81 |

| rincom06 | Respondent refuses to report income | 4.27 | 6.05 |

| famgen | Reports that there is only one generation in household | 53.26 | 57.12 |

| premarsx | Respondent reports that sex before marriage is always or almost always wrong | 34.94 | 30.75 |

| radioact | Correctly answers question about the source of radioactivity | 84.79 | 79.40 |

| viruses | Correctly answers question about efficacy of antibiotics | 65.64 | 59.35 |

| condrift | Correctly answers question about plate tectonics | 91.34 | 87.21 |

| electron | Correctly answers question about sizes of electrons/atoms | 75.77 | 70.45 |

Note : The 2006 cohort is restricted to respondents who were interviewed in 2006 and 2008; the 2008 cohort is restricted to respondents who entered the panel in 2008 and were also interviewed in 2010. Comparisons between cohorts are made in 2008, the year that they overlap in the sample. All of the variables presented in this table produced FDR adjusted p -values below .10, except for the science knowledge items. We included these items because of the consistency across measures (all four were significant by conventional standards and all four effects were in the same, theoretically sensible, direction). See text for more details, and Appendix Table A1 for the full set of results.

Second, panel conditioning effects emerged in several questions related to household composition. These include items dealing with the respondent’s relationship to the household head (members of the 2006 cohort were more likely to be the head or spouse), the number of adults present (members of the 2006 cohort reported more adults), the number of visitors present (members of the 2006 cohort reported more visitors), and the number of family generations that live with the respondent (members of the 2006 cohort reported more generations). The fact that experienced GSS respondents reported higher numbers in all of these cases may be related to our hypothesis concerning survey skill and/or trust. After completing the survey for the first time, respondents may become more willing to open up, to report on more people, or to ask follow-up questions about who qualifies as living in their household.20

Third, members of the 2006 and 2008 cohorts frequently differed in their responses to questions about demographic and economic attributes. Respondents with prior survey experience were 20% more likely to be divorced or widowed, 11% more likely to be upwardly mobile relative to their parents, and 31% less likely to refuse to answer questions about their personal income. Although we cannot provide definitive tests, these patterns could also be attributable to differences in respondents’ trust. As we discussed earlier, being interviewed repeatedly may make the interview process seem less threatening to the respondent, which could decrease their need to give guarded and/or socially desirable responses in the follow-up wave (van der Zouwen and van Tilburg 2001). That this would occur for potentially sensitive items like those listed above makes good theoretical sense.21

Finally, we found large and consistent differences between groups with respect to their knowledge about science. Although these differences were typically not below the FDR-adjusted p < 0.10 threshold, the frequency with which they occurred is at the very least suggestive of a “true” effect. As shown in Table 1, respondents in the treatment group were markedly more likely to answer correctly questions about the source of radioactivity (radioact), the efficacy of antibiotics in killing viruses (viruses), the ongoing process of plate tectonics (condrift), and the relative sizes of electrons and atoms (electron). One possible explanation for these results is the “learning hypothesis” that we proposed earlier: if respondents who previously participated in the GSS seek out information about questions that have one objectively correct answer, we would expect to see differences between cohorts on precisely these sorts of items.

A note on exceptions

Although the empirical patterns that we present in Table 1 are generally consistent with theoretical expectations, there are also plenty of counter-examples where the treatment and control groups did not differ in predictable or meaningful ways. We did not always find differences between cohorts when examining questions about socially-charged issues, nor did we observe significant effects for all items that required factual knowledge or increased levels of respondent trust (for the complete set of results, see Appendix Table A1). These inter-item inconsistencies do not invalidate our findings, but they do suggest the need for more finely-grained analyses that are capable of isolating and carefully testing the various hypotheses that we outlined earlier. We will return to this idea later on in the discussion section.

Falsification test

In the final part of our analysis, we carry out a falsification test to confirm the adequacy of our empirical approach. As a part of its mission to provide up-to-date information about a wide variety of topics, the GSS frequently introduces new survey content through the use of special topical modules. This allows us to perform an important methodological check. Using the same analytic setup as before, we can test for differences between cohorts on items that have not previously been answered by anyone in the sample, regardless of which cohort they belong to. In the absence of any contaminating influences, we would expect to see a similar distribution of responses across groups for these measures. Any other result (e.g., non-zero differences between the treatment and control groups on items that should not, in theory, differ) would call into question the internal validity of our empirical estimates.

We present results from these comparisons in Table 2. In total, there are 19 variables that (1) were not asked in 2006; (2) were asked of both cohorts in 2008; and (3) meet the selection criteria that we defined earlier. Among these items, only one (autonojb) shows any evidence of variation between cohorts, and that evidence disappears when corrections are made for multiple comparisons.22 None of the estimated tests are significant at a 0.01 level and only two reach significance at the 0.10 level (with 19 comparisons we would expect to see ~1 significant result by chance, assuming a Type 1 error rate of 0.05).23 This is a reassuring finding for our purposes, as it minimizes the possibility that the two cohorts differ in ways that could spuriously produce some or all of what we previously deemed to be panel conditioning effects.

Table 2.

Results from falsification tests

| Tests for differences between cohorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable description | Name | p | FDR-adjusted p |

| Trying to start a business | startbiz | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| Number of full-time jobs since 2005 | work3yrs | 0.67 | 0.78 |

| Number of years worked for current employer | curempyr | 0.54 | 0.75 |

| Amount of pay change since started job | paychnge | 0.40 | 0.75 |

| Was pay higher/lower/the same in previous job? | pastpay | 0.28 | 0.68 |

| Why did the respondent leave their previous job? | whyleave | 0.35 | 0.75 |

| Does more trade lead to fewer jobs in the U.S.? | moretrde | 0.27 | 0.68 |

| Computer use at work | wkcomptr | 0.12 | 0.66 |

| Can job be done without a computer? | wocomptr | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Have any co-workers been replaced by computers? | autonojb | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Frequency of meetings with customers, clients, or patients | meetf2f1 | 0.15 | 0.66 |

| Frequency of meetings with co-workers | meetf2f2 | 0.28 | 0.68 |

| Frequency of communication with co-workers outside the U.S. | intlcowk | 0.22 | 0.68 |

| Does the respondent receive health insurance from their employer? | emphlth | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Is there another name for the respondent's insurance or HMO policy? | othplan | 0.58 | 0.75 |

| Gender of sex partners | sexsex18 | 0.09 | 0.66 |

| Ever been the target of sexual advances by a co-worker/supervisor? | harsexjb | 0.55 | 0.75 |

| Has respondent been the target of a sexual advance by a religious leader? | harsexcl | 0.66 | 0.78 |

| Do they know others who have been the target of sexual advances? | knwclsex | 0.47 | 0.75 |

Note: These items were not asked of the 2006 cohort in 2006, but were asked of both cohorts in 2008. Variable names are given in the “name” column. The FDR-adjusted p is the p -value adjusted for the False Discovery Rate. Adjustments were made using the procedures of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). See text for more details.

Discussion

Sociologists who work with longitudinal data typically assume that the changes they observe across waves are real and would have occurred even in the absence of the survey. Whether or not this assumption is justified is an important empirical question, one that should be of concern to methodologists and non-methodologists alike. In this article, we provided an analytic framework for detecting panel conditioning effects in longitudinal surveys that include a rotating panel component. To demonstrate the utility of our approach, we analyzed data from recent waves of the GSS. Results from these analyses suggest that panel conditioning influences the quality of a small but non-trivial subset of core survey items. This inference was robust to a falsification test, and cannot be explained by statistical artifacts stemming from panel attrition and/or differential non-response.

What should applied researchers make of these findings? Our analysis suggests that panel conditioning exists in the GSS on a broad scale, but it is much less clear about the specific content domains that are most affected by this form of bias. As we mentioned at the outset, panel conditioning is a complex interactive phenomenon that involves a range of cognitive processes and subjective individual assessments. Predicting when and where it will occur is a difficult theoretical exercise. We have attempted to provide some guidance to users of the GSS by listing the variables that show the most evidence of possible effects. We would advise researchers to weigh this information carefully when conducting studies with these data. Although panel conditioning does not always present itself in an intuitive or internally consistent manner, it would be wrong to dismiss it as an unimportant methodological issue.

There is obviously much more work still to be done in this area. The analytic techniques described herein can be usefully applied in any longitudinal data set that contains overlapping panels. An interesting future application would be to examine heterogeneity in panel conditioning among different sub-groups of respondents. In our analysis, we sought to identify the average treatment effect taken over all members of the sample. In reality, these effects may vary considerably across individuals, across social contexts, and across topical domains (see, e.g., Zwane, Zinman, Van Dusen, Pariente, Null, Miguel, Kremer, Karlan, Hornbeck, Gine, Duflo, Devoto, Crepon, and Banerjee 2011). A treatment effect of zero in the population may nevertheless be non-zero for certain sub-groups with particular experiences and/or predispositions. Identifying who these individuals are, and how they differ from others, would go a long way toward refining our theoretical understanding of why panel conditioning occurs.

Another worthwhile extension would be to conduct stand-alone experiments that allow for a closer examination of possible mechanisms. These experiments would not need to be complicated; it would probably be enough to assign individuals at random to receive alternate forms of a baseline questionnaire and then to ask all questions of all individuals in a follow-up. To speak to the issue in a way that is broadly useful to sociologists, the questions would need to be similar or identical to those that routinely appear in other widely-used surveys, like the GSS, and would need to be carefully selected in order to isolate the various social and psychological processes that we described earlier. This would obviously require considerable effort and careful planning, but we believe it is the best way to produce a general and theoretically-informed understanding of panel conditioning in longitudinal social science research.

Footnotes

The National Science Foundation (SES-0647710) and the University of Minnesota’s Life Course Center, Department of Sociology, College of Liberal Arts, and Minnesota Population Center have all provided support for this project. We would like to thank Eric Grodsky, Michael Davern, Phyllis Moen, Chris Uggen, and Scott Long for their helpful comments and suggestions. Any errors, however, are solely our responsibility.

We use the term “panel conditioning” synonymously with what has been called, among other things, “time-in-survey effects” (Corder and Horvitz 1989), “mere measurement effects” (Godin, Sheeran, Conner, and Germain 2008), “question-behavior effects” (Spangenberg, Greenwald, and Sprott 2008), and “self-erasing errors of prediction” (Sherman 1980).

Researchers whose analysis only includes first-time GSS respondents (or who are only analyzing data that were collected prior to 2008) do not need to worry about panel conditioning effects.

Similar hypotheses can be found in reviews by Cantor (2008), Sturgis et al. (2009), and Waterton and Lievesley (1989).

Examples from the GSS include questions that deal with respondents’ racial attitudes, their history of substance use, their sexuality, their past criminal behavior, and their fidelity to their spouse or partner.

It is important to distinguish these sorts of changes from social desirability bias. In some cases, the mere thought of providing a non-normative answer may cause respondents to alter the way that they characterize themselves on a baseline survey and in all subsequent interviews (Tourangeau and Yan 2007). In other cases, the experience of admitting to something that is socially undesirable may change the way respondents describe themselves in later waves—because of the feelings of embarrassment or shame that the initial interview provoked. Although both of these things could be happening at the same time within the same survey, our focus in this article is only on the latter problem. For more information about the former problem, the interested reader should see Schaeffer (2000) and Tourangeau and Yan (2007).

This question answering strategy can be thought of as a very strong form of satisficing. Not only are respondents seeking to provide “merely satisfactory answers” (Krosknick 1991), they are also deliberately seeking to avoid additional follow-up questions.

This sort of “burden avoidance” behavior can also occur within the context of a cross-sectional survey if respondents learn, through repetition, that certain types of answers lead to additional items (see, e.g., Kessler, Wittchen, Abelson, McGonagle, Schwarz, Kendler, and Knauper 1998; Kreuter, McCulloch, Presser, and Tourangeau 2011). We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

We know of two previous analyses that have examined panel conditioning effects in the GSS (Smith and Son 2010; Warren and Halpern-Manners 2012). Both focused on a fairly narrow subset of survey items (n < 25), and neither ruled out alternative explanations for the observed results (including selective attrition, random measurement error, and social desirability bias). The present article represents an improvement on both fronts.

Other widely-used, nationally representative surveys that employ a rotating panel design include the Current Population Survey and the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Panel conditioning effects have been assessed in both of these surveys (Bailar 1975; Halpern-Manners and Warren 2012; McCormick, Butler, and Singh 1992; Solon 1986), but only for a very select subset of items.

Both sets of respondents were probably also subject to similar levels of non-response bias, although this is not something that we can verify using available data.

The age distribution of respondents will vary slightly between cohorts because the treatment group has aged two years since their initial interview (and thus cannot be 18 or 19 years old), whereas the control group has not. In supplementary analyses, we truncated the age distribution so that all respondents were above the age of 20 in 2008 and then recalculated our estimates. The results were substantively identical and are available from the first author upon request.

We only use the 2010 data for the purposes of sample selection; we do not actually analyze respondents’ answers from that wave of the survey.

Random sampling in two different years (e.g., 2006 and 2008) does not guarantee the same population characteristics when the composition of the population changes gradually over time. To confirm that the differences we attribute to panel conditioning are not due to slight compositional changes that occurred between 2006 and 2008, we fit a series of auxiliary models that included controls for various socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, householder status, and race/ethnicity). Our conclusions with respect to panel conditioning were robust to the inclusion of these variables.

This approach would provide invalid results if there is an important attrition-by-cohort interaction. Even if members of the 2006 and 2008 cohorts were equally likely to leave the sample, it may still be the case that attriters from these cohorts differ with respect to socioeconomic, demographic, or other attributes that might predict responses to the survey items we consider. To explore this possibility, we pooled our data files and ran a regression model predicting attrition. For independent variables, we included indicators of the respondent’s age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, region of residence, marital status, party affiliation, household size, happiness, and health. We then created interactions between these measures and the respondent’s cohort. None of these interactions were significant at the p < 0.05 level. This provides reassurance that the process generating attrition was similar across groups.

A third stipulation is that the variables under consideration had to appear on the 2006 and 2008 waves of the survey. For the most part, this limits our analysis to items that belong to the GSS’s replicating core.

In very rare instances (n = 7), results for a Fisher’s exact test could not be obtained for computational reasons. In these cases, we consolidated response categories to reduce data sparseness and then carried out chi-square tests instead.

Core GSS items appeared in the same order for both cohorts of respondents in 2008.

Q-Q plots are widely used in genetics research to visualize results from large numbers of hypothesis tests (see, e.g., Pearson and Manolio 2008). To draw the plot, we rank-ordered the p-values (n = 1, …, 310) from smallest to largest and then graphed them against the values that would have been expected had they been sampled from a uniform distribution. As noted above, the red line indicates the expectation under the null and the black circles represent the actual results. Following convention, we show the relevant test statistics as the – log10 of the p-value, so that an observed p = .01 is plotted as “2” on the y-axis and p = 10−5 as “5.”

The null hypothesis that the observed values are uniformly distributed was easily rejected using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (D = 0.18, p < .0001).

These variables are not good candidates for “burden” effects because respondents receive very few additional questions for each household member that they report.

We also found that members of the 2006 cohort were much more likely to give out information about their home phone. This is, again, consistent with a “trust” effect.

We excluded three employment-related variables (ownbiz, findnwjb, and losejb12) from these analyses because they closely resemble items that appeared on the 2006 survey. One of these variables produced a significant difference between cohorts; the other two did not.

None of the comparisons were significant after adjusting the p-values for the FDR, and a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test could not reject the null hypothesis that the distribution of results was uniform (D = .21, p = 0.81).

Contributor Information

Andrew Halpern-Manners, Indiana University.

John Robert Warren, University of Minnesota.

Florencia Torche, New York University.

References

- Bailar Barbara A. Effects of Rotation Group Bias on Estimates from Panel Surveys. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1975;70:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bailar Barbara A. Information Needs, Surveys, and Measurement Errors. In: Kasprzyk D, Duncan GJ, Kalton G, Singh MP, editors. Panel Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Yoav, Hochberg Yosef. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor David. A Review and Summary of Studies on Panel Conditioning. In: Menard S, editor. Handbook of Longitudinal Research: Design, Measurement, and Analysis. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Casella George, Berger Roger L. Statistical Inference. New York: Duxbury Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton Joshua D. Stanford University: Department of Political Science; 2001. [April 5, 2006]. Panel Bias from Attrition and Conditioning: A Case Study of the Knowledge Networks Panel. Unpublished manuscript, retreived from http://www.princeton.edu/~clinton/WorkingPapers/C_WP2001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Corder Larry S, Horvitz Daniel G. Panel Effects in the National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey. In: Kasprzyk D, Duncan GJ, Kalton G, Singh MP, editors. Panel Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 304–318. [Google Scholar]

- Das Marcel, Toepoel Vera, van Soest Arthur. Nonparametric Tests of Panel Conditioning and Attrition Bias in Panel Surveys. Sociological Methods & Research. 2011;40:32–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Don A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. New York: John Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duan Naiuhua, Alegria Margarita, Canino Glorisa, McGuire Thomas G, Takeuchi David. Survey Conditioning in Self-reported Mental Health Service Use: Randomized Comparison of Alternative Instrument Formats. Health Services Research. 2007;42:890–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Jack M, Lynch John G. Self-Generated Validity and Other Effects of Measurement on Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1988;73:421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman Andrew, Hill Jennifer, Yajmia Masanao. Why We (Usually) Don't Have to Worry About Multiple Comparisons. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness. 2012;5:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Godin Gaston, Sheeran Paschal, Conner Mark, Germain Marc. Asking Questions Changes Behavior: Mere Measurement Effects on Frequency of Blood Donation. Health Psychology. 2008;27:179–184. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Manners Andrew, Robert Warren John. Panel Conditioning in the Current Population Survey: Implications for Labor Force Statistics. Demography. 2012;49:1499–1519. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, Wittchen Hans-Ulrich, Abelson Jamie A, McGonagle Katharine, Schwarz Norbert, Kendler Kenneth S, Knauper Barbel, Shanyang Zhao. Methodological Studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter Frauke, McCulloch Susan, Presser Stanley, Tourangeau Roger. The Effects of Asking Filter Questions in Interleafed Versus Grouped Format. Sociological Methods & Research. 2011;40:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Krosknick Jon A. Response Strategies for Coping with the Cognitive Demands of Attitude Measures in Surveys. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1991;5:213–236. [Google Scholar]