Abstract

Understanding the genetic architecture of speciation is a major goal in evolutionary biology. Hybrid dysfunction is thought to arise most commonly through negative interactions between alleles at two or more loci. Divergence between interacting regulatory elements that affect gene expression (i.e., regulatory divergence) may be a common route for these negative interactions to arise. We review here how regulatory divergence between species can result in hybrid dysfunction, including recent theoretical support for this model. We then discuss the empirical evidence for regulatory divergence between species and evaluate evidence for misregulation as a source of hybrid dysfunction. Finally, we review unresolved questions in gene regulation as it pertains to speciation and point to areas that could benefit from future research.

Keywords: speciation, hybrid sterility, hybrid inviability, gene regulation, gene expression

A Role for Gene Regulation in Hybrid Sterility and Inviability

Understanding the genetic basis of speciation is a longstanding problem in evolutionary biology. The major model for the evolution of intrinsic post-zygotic isolation postulates that hybrid sterility or inviability arises from negative interactions between alleles at different loci when joined together in hybrids. The regulation of gene expression is inherently based on interactions between loci, raising the possibility that disruption of gene regulation in hybrids is a common mechanism for post-zygotic isolation. Although there is accumulating evidence that changes in gene regulation play a prominent role in adaptation (e.g., [1,2]), the role of regulatory evolution in speciation has received less attention. We evaluate here the role of regulatory evolution in speciation, and we suggest, both from recent theoretical and empirical studies, that changes in gene regulation play a major role in intrinsic post-zygotic isolation. While our focus is on post-zygotic isolation, regulatory divergence may also play an important role in establishing other reproductive barriers as a byproduct of adaptive divergence (i.e., ecological speciation).

Conceptual Framework

Single-locus models of hybrid dysfunction all suffer from the problem that mutations that lower the fitness of heterozygotes (and thus cause reproductive isolation) are unlikely to become established in a new population (e.g., [3–5]). This problem was recognized by Bateson [6], Dobzhansky [7], and Muller [8,9], who suggested instead that hybrid dysfunction could arise from negative interactions between alleles at two or more loci. In the Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller (BDM) model, alleles that are adaptive or neutral in their own genetic background are incompatible with alleles at one or more loci on the alternative genetic background (Figure 1). Thus, diverging lineages can accumulate substitutions without any loss of fitness. There is now strong empirical support for this model of intrinsic post-zygotic isolation [10].

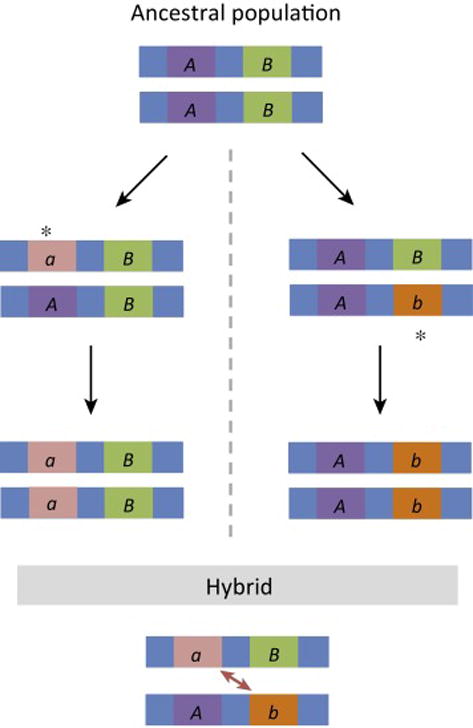

Figure 1.

The Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller Model of Hybrid Incompatibility. In the ancestral population, the genotype is AABB. After the two populations are isolated, new mutations arise independently on each lineage as indicated by the asterisks. In one population, A evolves into a, in the other population B evolves into b. In hybrids, negative interactions between the a and b alleles can result in sterility or inviability. The a and b alleles are found together for the first time in hybrids, explaining how this incompatibility could evolve without either lineage experiencing an intermediate state of reduced fitness.

Gene regulation is the process by which cells control the specific amount of gene product (i.e., RNA or protein) produced. Gene regulation is a complex process involving the interaction of DNA sequences, RNA molecules, and proteins, as well as epigenetic modifications. Because the interaction of regulatory elements is required for organismal function, interacting regulatory elements are assumed to be co-adapted (e.g., [11]). When co-adapted interactions between regulatory elements are disrupted, downstream targets of these elements may be misregulated. While disrupted interactions between any of pair of regulatory elements or sequences could result in hybrid incompatibilities, the process of transcription initiation has received the most attention. While we focus mainly on transcriptional control, divergence between regulatory elements affecting other levels of gene regulation (e.g., translation) may also play a role in speciation.

Transcription is regulated by the interaction of cis-regulatory elements and trans-acting factors. Cis-regulatory elements are stretches of non-coding DNA (i.e., promoters, enhancers) that act as binding sites for trans-acting factors to regulate mRNA abundance. In the simplest case, the trans-acting factors are transcription factor proteins, although other proteins have also been known to act in trans to regulate gene expression [12]. Mutations in cis-regulatory regions or in transcription factors can affect mRNA abundance. Transcription factors frequently interact with multiple downstream target sequences and thus may be pleiotropic. By contrast, a single gene may have multiple cis-regulatory regions that regulate it in a tissue-and context-specific manner. As a consequence, changes in cis-regulatory regions are thought to be less pleiotropic than changes to the transcription factors they bind. The modularity of cis-regulatory regions has given rise to the idea that changes to these regions may play a large role in phenotypic evolution, an idea that is now well supported by empirical research [13,14]. However, while transcription factors are assumed to evolve more slowly than cis-regulatory regions, they can evolve quickly compared to other gene classes [15]. Changes to transcription factor proteins have also been implicated in the evolution of novel phenotypes (e.g., [16]).

Despite the role of transcriptional variation in phenotypic evolution, mRNA levels are often constrained on long timescales [17]. Genome-wide comparisons of mRNA levels between species show widespread reductions in divergence compared to neutral expectations [18–20], suggesting that changes in transcript levels are frequently deleterious. Despite the existing constraint on transcript levels, gene regulatory networks themselves are not necessarily well conserved between species [21]. Interestingly, data on mRNA abundance from yeast, worms, and flies suggest that expression evolution best fits a ‘house of cards’ model of stabilizing selection [22] in which mutations generally have large effects that exceed the standing genetic variation [23,24]. As a consequence, mutations that affect mRNA abundance can bring down the evolutionary house of cards and cause a cascade of changes between co-evolved cis and trans factors within a gene regulatory network.

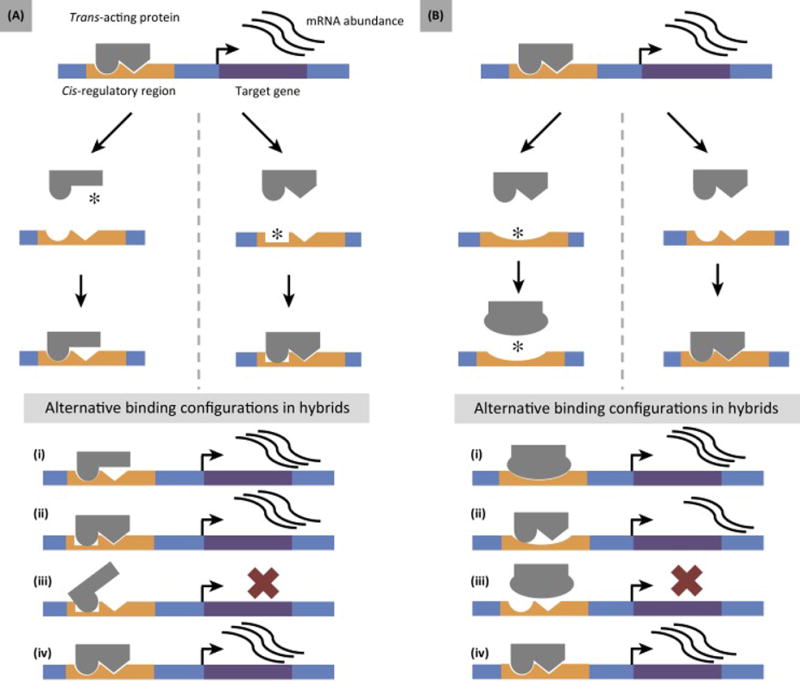

Given these theoretical and empirical considerations, the epistatic interactions that underlie gene regulatory networks may lead to dysfunction in hybrids. In the simplest case, regulatory incompatibilities may arise either as a result of (i) the independent divergence of interacting elements between lineages (Figure 2A) or (ii) lineage specific co-evolution between elements (Figure 2B). In the first model, populations respond differently to drift or parallel or opposing directional selection. One population fixes a cis-regulatory change, the other fixes a trans change. In the second model, a cis change that affects expression is compensated for by changes to an interacting trans-acting factor, or vice versa. In either model, negative interactions between divergent regulatory elements in hybrids may result in the misregulation of downstream targets. More complicated models are possible, including cis and trans changes in both lineages or interactions between more than two loci.

Figure 2.

Regulatory Divergence as a Source of Hybrid Incompatibilities. Panels (A) and (B) are schematics of a two-locus model for hybrid incompatibilities. Each hybrid incompatibility arises as a consequence of the molecular interactions between a cis-regulatory region and a trans-acting factor. Changes in binding between interacting regulatory elements affect the expression of a downstream gene. Asterisks represent mutations that become fixed along a lineage. (A) A change to a cis-regulatory region in one species and the interacting trans-acting factor in the other result in hybrid dysfunction. Divergence in this example may be the result of drift or selection. In hybrids, the binding configuration represented by (iii) results in misregulation, while (i), (ii), and (iv) produce normal transcriptional output. This model is a realization of the Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model. (B) Lineage specific co-evolution between cis- and trans-regulatory elements result in hybrid dysfunction. In this example, a change in cis is followed by a compensatory change in trans to mask the deleterious effect of the first mutation. In hybrids, the binding configuration represented by (iii) results in misregulation. The binding configuration represented by (ii) results in reduced expression compared to the parents, while the binding configurations represented by (i) and (iv) result in the same expression as in the parents.

Recent simulations and mathematical models indicate that these types of regulatory incompatibilities can evolve quickly if selection is acting [25–29]. In particular, regulatory incompatibilities will evolve most quickly as a byproduct of adaptation when cis and trans regulatory elements diverge under positive selection [25,28]. Incompatibilities will evolve more slowly under a model of stabilizing selection, where compensatory changes follow genetic drift [28]. Because transcription factors often regulate the expression of many genes, opposing selective pressures may constrain functional divergence and slow the evolution of regulatory incompatibilities. However, it was recently shown that it is possible for substantial hybrid misregulation to arise even when transcription factors are under moderate pleiotropic constraint [30].

Regulatory Divergence Between Species Is Widespread

Recent genomic surveys have found abundant evidence for transcriptional regulatory divergence between species. Divergence in putative cis-regulatory regions can be inferred through comparisons of transcription factor binding sites between species. While the loss and gain of transcription factor binding sites has generally been rapid over evolutionary time [31], examination of individual cis-regulatory elements has demonstrated that regulatory function can be maintained despite significant sequence divergence [32–34]. This observation may be explained by the fixation of functionally compensatory mutations.

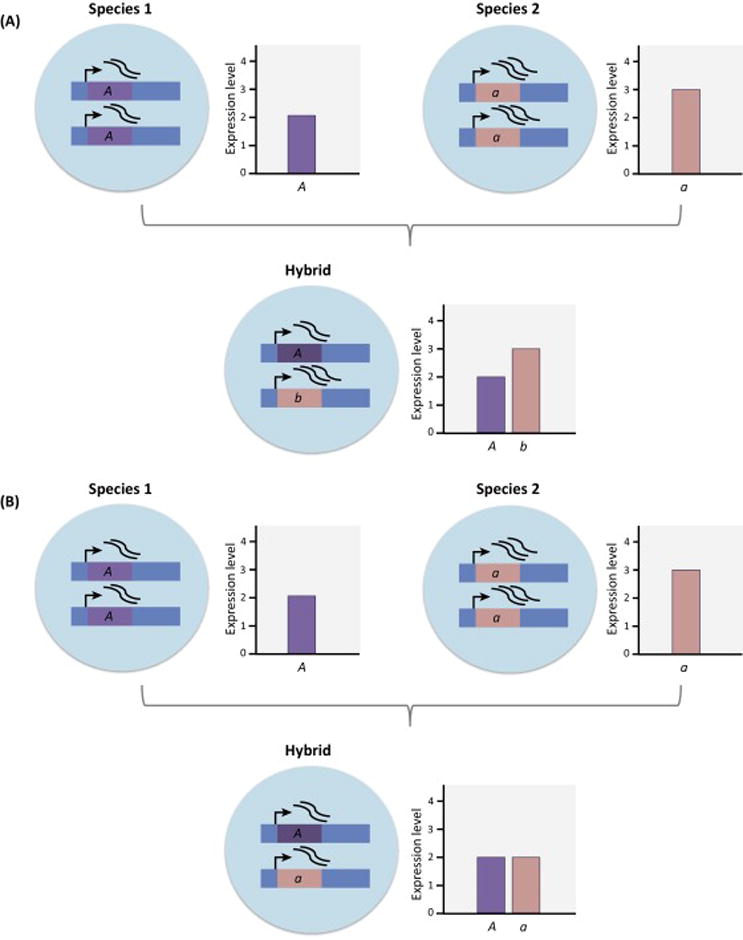

Regulatory divergence affecting the expression of individual genes can also be inferred through interspecific crosses. In F1 hybrids, differences in transcript abundance between two alleles indicates that differences between the parents at this locus are due to changes in cis because the two alleles in the F1 are in a common trans-acting environment [35] (Figure 3A). By contrast, if the two alleles in the F1 show the same level of transcript abundance, this indicates that differences between the parents are due to changes in trans [36] (Figure 3B), although interpretation can be complicated by dominance in regulatory pathways [37]. This approach has now been used to study genome-wide regulatory divergence between species of mice, birds, flies, yeast, and plants (e.g., [38–42]). Interspecific divergence in cis and trans is common, with cis-regulatory variants generally contributing more to divergence between species than variation within species [41,43,44]. However, a significant proportion of regulatory divergence can be attributed to a combination of cis- and trans-acting variants. When cis and trans changes are found together, interactions between them can increase or decrease gene expression divergence between species. When cis and trans variants act in opposition, their effects may buffer one another in a compensatory fashion. Consistent with stabilizing selection, such cis–trans compensation appears to play a prominent role in regulatory evolution [38,41,42,45,46].

Figure 3.

Using Allele-Specific Expression To Infer Regulatory Divergence between Species. Differences in the expression of alleles in an F1 can be used to determine whether expression divergence between the parents is due to changes in cis or to changes in trans. (A) Species 1 carries the A allele while species 2 carries the a allele. In the parental species, the transcript abundance of A is 2 and the transcript abundance of a is 3. Differences in the expression of the A and a alleles in the F1 hybrid suggests cis-regulatory divergence between species 1 and 2 because these two alleles are in the same trans-acting environment in the F1. (B) A and a have equal transcript abundances in the F1 hybrid despite the difference in expression seen between the parents. This suggests that differences between the parents are due to changes in trans.

The proportion of genes with cis–trans divergence has also been shown to accumulate with phylogenetic distance. Transgenic assays called ‘enhancer swaps’, where orthologous regulatory regions are tested in the same trans-acting environment, have found that lineage-specific cis–trans evolution is more common in comparisons between distant than closely related taxa [47]. Similarly, pairwise comparisons between species of Drosophila found that, although the number of genes with cis-regulatory divergence increased linearly with divergence time, the number of genes with total expression divergence does not [44]. This suggests that cis changes are often compensated for by changes in trans variants, or by other trans-regulatory feedback mechanisms [48–50].

A few clear cases of such cis–trans compensatory evolution have now been reported [51,52]. In the nematodes Caenorhabditis elegans and C. briggsae, the expression of the gene unc-47 is conserved between species even as its regulation has changed. Reciprocal swaps of C. briggsae and C. elegans regulatory elements identified lineage-specific changes consistent with compensatory cis–trans evolution. Regions in the C. briggsae unc-47 promoter have co-evolved with specific changes in the C. briggsae trans-regulatory environment. Compensatory modifications in regulatory elements associated with unc-47 represent an example of how gene expression can be maintained despite underlying regulatory divergence [52].

Misregulation as a Mechanism for Hybrid dysfunction

Misregulation of genes in hybrids can lead to misexpression, defined as gene expression that falls outside the range of the parental species. Novel interactions between divergent cis and trans variants are one way misexpression can arise in hybrids. Consistent with this prediction, a number of studies have associated misexpression with cis–trans compensatory evolution ([40,41,46,53,54], but see also [44,55]). Misexpression is commonly seen in sterile interspecific hybrids [56–61] and has been shown to accumulate with phylogenetic distance in Drosophila [44].

In some interspecific hybrids, abnormal expression is disproportionately observed in male-biased genes [56,57] and genes involved in spermatogenesis [62,63], suggesting that regulatory divergence might underlie some cases of hybrid male sterility. Comparisons between sterile and fertile hybrids of Drosophila species [64] and of house mouse subspecies [46,61] have found that a greater number of genes are misexpressed in sterile hybrids than in fertile hybrids. Moreover, in house mice, some expression quantitative trait loci (QTL) colocalize with sterility QTL in hybrids, suggesting a causal role for regulatory changes in hybrid male sterility [65]. Also in mice, misexpression in sterile hybrids is associated with compensatory cis–trans changes, consistent with a model where disrupted interactions between these types of loci contribute to hybrid sterility [46].

The X chromosome often plays a central role in post-zygotic isolation [10,66]. If regulatory divergence underlies hybrid dysfunction, evolutionarily diverged regulation of sex-linked genes may be expected [67]. Several recent studies have found that expression diverges faster for some genes on the X (in XY taxa) and Z (in ZW taxa) chromosomes than on the autosomes between species [68–73]. Faster divergence of sex-linked gene expression is especially strong for genes with sex-biased effects (male-biased effects in XY taxa and female-biased effects in ZW taxa) [69,70,71,74]. However, comparisons of expression patterns in whole tissues may obscure differences in individual cell types. For example, it was recently shown that expression evolution for X-linked genes depends on the developmental stage of spermatogenesis, with genes expressed late in spermatogenesis showing slower divergence on the X [75]. Disproportionate misexpression of X-linked genes has also been reported for sterile hybrids [61,65,74,76].

There are several caveats to bear in mind when considering whether misexpression is causing hybrid sterility or inviability. First, the widespread misexpression seen in many interspecific crosses can be the result of one or a few upstream changes that cause a cascading effect on genes downstream in a regulatory network [77]. This has been seen in hybrids between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. paradoxu, where misexpression is primarily due to a shift in the timing of meiosis [78]. Second, while misexpression in interspecific hybrids has been the subject of intense scrutiny, misexpression has also been observed in intraspecific hybrids where dysfunction is absent [44,79]. Third, changes in cellular composition can also conflate associations between hybrid dysfunction and misexpression. Sterile and inviable animals often have gonads of differing cellular composition or suffer from atrophied tissue relative to their fertile counterparts. Because many studies isolate mRNA from whole animals or whole tissues, differences in tissue or cellular composition between sterile or inviable hybrids and parental species can produce misexpression. As a result, hybrid misexpression that is a direct result of regulatory divergence is likely to be overestimated [80]. In the future, studies that make use of sorted cell populations may mitigate this problem somewhat by comparing gene expression only in equivalent cell types [75,81,82].

Evidence from Speciation Genes

Misexpression identified in sterile hybrids provides only indirect evidence of the role of misregulation in hybrid dysfunction. ‘Speciation genes’ – defined here as genes that contribute to reproductive isolation – provide the best direct evidence for the role of regulatory divergence in reproductive isolation. Unfortunately, relatively few speciation genes have been identified and molecularly characterized [83,84]. Despite this limitation, some broad-scale patterns have started to emerge. Of the speciation genes identified so far, many have either a putative role in transcriptional or translational regulation, or are themselves misexpressed in hybrids (Table 1). While this pattern is intriguing, it is necessary to characterize the molecular and physiological basis of hybrid dysfunction in each case to determine whether regulatory divergence is causal. We discuss a few speciation genes that have been particularly well characterized in Drosophila and house mice, highlighting some of the challenges in linking specific mutations to misregulation.

Table 1.

Hybrid Incompatibility Genes

| Locus | Gene name | Species | Phenotype | Molecular function | Evidence of gene regulationa | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEP2 | ATPase expression 2 | Saccharomyces bayanus × S. cerevisiae | Sterility | Mitochondrial protein | Regulates translation of OLI1 transcripts | [118] |

| OLI1 | Oligomycin resistance 1 | S. bayanus × S. cerevisiae | Sterility | F0-ATP synthase subunit | Impaired translation in hybrids | [118] |

| Ods | Odysseus | Drosophila mauritiana × D. simulans | Sterility | Regulation of heterochromatic sequences | Encodes a DNA-binding protein that localizes to heterochromatic regions and regulates their decondensation | [126,127] |

| agt | O-6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase | D. mauritiana × D. simulans | Sterility | DNA binding protein | Encodes a DNA-binding protein for an alkyl-cysteine-S-alkyltransferase | [128] |

| Taf1 | TBP-associated factor 1 | D. mauritiana × D. simulans | Sterility | Transcription factor component | Encodes a DNA-binding protein for a subunit of transcription factor TFIID | [128] |

| Hmr | Hybrid male rescue | D. melanogaster × D. simulans | Inviability | Regulation of heterochromatic sequences | Overexpression of HMR/LHR complex in hybrids | [129] |

| Lhr | Lethal hybrid rescue | D. melanogaster × D. simulans | Inviability | Regulation of heterochromatic sequences | Overexpression of HMR/LHR complex in hybrids | [85] |

| gfzf | Suppressor of Killer-of-prune [Su(Kpn)] | D. melanogaster × D. simulans | Lethality | Cell-cycle regulation | Transcriptional regulator of the RAS/MAPK pathway | [130] |

| Nup160 | Nucleoporin 160 | D. simulans × D. melanogaster | Inviability | Nuclear pore protein | None | [111] |

| Nup96 | Nucleoporin 96 | D. simulans × D. melanogaster | Inviability | Nuclear pore protein | None | [110] |

| Ovd | Overdrive | D. pseudoobscura bogatana × D. p. pseudoobscura | Sterility | DNA binding | Encodes a MADF DNA-binding domain | [131] |

| Hhl | heterochromatin hybrid lethal | D. melanogaster × D. simulans, D. mauritiana, D. sechellia | Lethality | Unknown | Unclear | [132] |

| Zhr | Zygotic hybrid rescue | D. melanogaster × D. simulans | Inviability | Unknown, repetitive DNA | Unclear | [133] |

| Prdm9 | PR/SET domain-containing 9 | Mus musculus musculus × M. m. domesticus | Sterility | Mediates meiotic homologous recombination | Encodes DNA-binding domains associated with transcription al regulation | [99] |

| DM1/DM2 | DANGER OUS MIX 1/2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Lethality | Disease resistance | None | [134] |

Putative evidence for regulatory function or of misexpression in hybrids for hybrid incompatibility genes.

Hybrid male rescue (Hmr) and Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr)

Hybrid male lethality in crosses between D. melanogaster and D. simulans can be explained in part by the genes Hmr and Lhr. The protein products of Hmr and Lhr form a complex that localizes to heterochromatic regions of the genome [85,86] where they transcriptionally repress transposable elements and repetitive sequences [86,87] and play a crucial role in mitotic chromosome segregation [86].

Loss-of-function mutations at Lhr in D. simulans or at Hmr in D. melanogaster restore hybrid male viability [85,88–90]. The D. simulans and D. melanogaster orthologs of both genes have diverged extensively under positive selection [85]. These observations led to the prediction that adaptive functional divergence between Hmr, Lhr, and species-specific heterochromatin sequences causes hybrid dysfunction. However, orthologs of Lhr appear to be functionally equivalent: sequence divergence between Lhr orthologs does not affect the localization of the Lhr protein, and overexpression of either the D. simulans or D. melanogaster ortholog has hybrid lethal effects [91].

Hybrid lethality is instead a consequence of species-specific changes in the abundance of Hmr and Lhr protein products. HMR expression is higher in D. melanogaster, and LHR expression is higher in D. simulans. Increased expression of HMR in D. melanogaster and LHR in D. simulans results in an elevated amount of the HMR–LHR complex in hybrids. The activity of the HMR–LHR complex is dosage-dependent, and overexpression leads to mislocation of the complex [86].

Because hybrid lethality is a consequence of HMR–LHR overexpression, the observed asymmetric lethal effects of D. melanogaster Hmr and D. simulans Lhr are likely the result of divergence in regulatory pathways between D. melanogaster and D. simulans rather than of functional divergence between orthologs [92]. Supporting this hypothesis, transcriptional differences between Lhr orthologs in hybrids has been linked to compensatory cis-by-trans divergence between species in allele-specific expression [92,93].

PR/SET domain 9 (Prdm9)

Crosses between Mus musculus domesticus and M. m. musculus produce sterile hybrid males [94]. A series of laboratory mapping experiments by Forejt and colleagues [95–98] led to the positional cloning and identification of Prdm9 [99], the only known hybrid sterility gene in vertebrates. Prdm9 is believed to interact with so far uncharacterized loci on the X chromosome and autosomes to cause spermatogenic failure in hybrids [100,101]. Sterile hybrid males show sex-specific failure to pair chromosomes during meiosis as well as misexpression of genes on the X and Y chromosomes [76]. While Prdm9 contains conserved domains associated with transcriptional regulation [102,103], the effect of Prdm9 on misexpression may be a secondary consequence of the role of Prdm9 in meiotic recombination.

Prdm9 has been implicated in recombination rate variation in both humans and mice [104–106]. During meiosis in mammals, double-stranded breaks are created throughout the genome and then repaired, leading to homologous recombination. These breaks are concentrated in regions called recombination hotspots. In mice, PRDM9 appears to mediate the process of recombination at hotspots by binding to DNA sequences [104]. Intriguingly, another QTL implicated in recombination rate variation was recently found to overlap with a hybrid male sterility QTL on the X chromosome [107]. Altogether, these results suggest a genetic connection between recombination and hybrid sterility [108].

Variation in the number of PRDM9 zinc-finger tandem repeats has been implicated in house mouse sterility [99]. The PRDM9 zinc-finger array co-evolves with species-specific binding sites. Meiotic drive against recombination hotspots is thought to result in the rapid turnover of these binding sites. Species-specific erosion of PRDM9 binding sites may explain asymmetric binding of PRDM9 in F1 hybrids that is associated with hybrid sterility. Supporting this prediction, hybrid fertility can be rescued by replacing the sterility-associated zinc-finger array with an orthologous region from humans [109]. While it is clear that sterile hybrid males show misexpression of genes on the X and Y chromosomes, the direct role, if any, of Prdm9 in this misexpression remains unclear.

Open Questions and Future Directions

While the evidence so far suggests that changes in gene regulation may contribute to the origin of new species, there are also cases where hybrid incompatibility appears to be independent of regulatory changes. For example, the speciation genes Nup160 and Nup96 cause hybrid inviability in crosses between Drosophila simulans and D. melanogaster. The protein products of both genes form architectural components of the nuclear pore complex and show evidence of adaptive protein evolution [110,111]. We do not wish to provoke a debate on the relative importance of coding versus regulatory mutations to speciation; both surely occur and both are likely to be important in some instances. Instead, we offer several research directions that are likely to be particularly useful in understanding the connection between regulatory divergence and speciation (see Outstanding Questions).

First, the study of speciation has benefited from studies of natural populations and from studies that utilize laboratory crosses. However, most of what is known about the role of regulatory divergence in speciation comes from laboratory studies. These studies represent a small sliver of phylogenetic diversity and they rely mainly on model systems (Table 1). If we are interested in understanding generalities of the speciation process, greater taxonomic sampling is necessary. It would also be useful to compare patterns of gene expression in naturally-occurring hybrid individuals that contain mixed genetic backgrounds to those seen in laboratory crosses.

Second, there are two aspects of many natural populations that merit further study: the presence of later-generation hybrids and the fact that alleles contributing to reproductive isolation may be polymorphic rather than fixed [112]. Studying both of these issues in the context of the role of regulatory divergence and reproductive isolation is important. For example, while great progress has been made studying F1 hybrids, using F2 or later-generation hybrids makes it possible to identify disrupted gene expression caused by recessive alleles [65].

Third, most of the focus has been on the role of regulatory divergence in intrinsic post-zygotic isolation. The role of regulatory divergence in other forms of reproductive isolation (i.e., ecological, mating, and gametic) is still largely unexplored. Regulatory divergence may commonly lead to phenotypic differences between populations that result in different types of reproductive barriers. In particular, to the extent that changes in gene regulation underlie adaptive evolution, such changes may be fairly common in ecological speciation, but this remains to be shown.

Fourth, there is a need to better integrate speciation theory with empirical evidence from gene expression studies. For example, the exposure of recessive mutations on the X (or Z) chromosome in heterogametic hybrids (i.e., XY males or ZW females) has been invoked to explain observations such as Haldane’s rule and the large X effect [10,113,114]. According to this hypothesis, many of the alleles that decrease hybrid fitness are at least partially recessive. It is possible to test the dominance of expression inheritance using crosses or chromosome substitution lines [79,82,115], and this would help to link theoretical predictions with empirical observations of gene expression. Similarly, BDM incompatibilities are predicted to accumulate at a non-linear rate over evolutionary time, resulting in a ‘snowball’ effect [116]. Controlled gene expression studies may be able to determine whether regulatory incompatibilities conform to this prediction and increase nonlinearly with phylogenetic distance.

Fifth, the evolutionary forces that drive regulatory divergence and contribute to hybrid incompatibilities remain largely unknown. Many of the known speciation genes show a signature of positive selection [83]. While this observation is consistent with a model of adaptive divergence driving the evolution of hybrid incompatibilities, a model of compensatory evolution is equally possible. Compensatory evolution requires positive selection to fix compensatory changes to mask the deleterious effects of an earlier mutation. Finally, while there is significant interest in the role of regulatory divergence in speciation, transcriptional control has received nearly all the attention. The regulation of gene expression is a complex process that may be modulated at many stages, including transcription, translation, and post-translation [117]. The yeast speciation genes AEP2 and OLI1 provide one example of how translational misregulation can result in hybrid sterility. AEP2 encodes a mitochondrial protein that translationally regulates OLI1. In interspecific hybrids of S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus, the Aep2 protein is unable to bind to OLI1 transcripts. The inability of Aep2 to mediate the translation of OLI1 is thought to result in hybrid sterility [118]. Advances have made the study of post-transcriptional regulation more feasible [119]. Allele-specific analyses of translational efficiency can now be used to infer cis and trans divergence acting on translation rate [120–122]. QTL mapping techniques have been employed to study intraspecific variation in translation and protein abundance [117,123–125]. Studies that combine each of these levels will provide a more complete picture of the role of regulatory divergence in speciation.

Trends.

Simulation studies suggest that hybrid incompatibilities can evolve rapidly when selection acts on regulatory pathways.

Genomic approaches have identified widespread regulatory divergence between species in cis and trans.

Cis–trans regulatory divergence increases with phylogenetic distance and has been associated with misexpression in interspecific hybrids.

Many known hybrid incompatibility genes have either a putative regulatory function or are misexpressed in hybrids.

Outstanding Questions.

Does regulatory divergence contribute to other reproductive barriers such as mating isolation, gametic isolation, or ecological isolation?

Do disrupted interactions between post-transcriptional regulatory elements contribute to hybrid dysfunction?

Does dysregulation typically arise as a consequence of strictly adaptive evolution or as a consequence of compensatory evolution?

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Barbash, Jiri Forejt, Norman Johnson, Bret Payseur, Adam Porter, Patricia Wittkopp, and one anonymous reviewer for their thoughtful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grant R01 GM074245 to M.W.N.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chan YF, et al. Adaptive evolution of pelvic reduction in sticklebacks by recurrent deletion of a Pitx1 enhancer. Science. 2010;327:302–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1182213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones F, et al. The genomic basis of adaptive evolution in threespine sticklebacks. Nature. 2012;484:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lande R. Effective deme sizes during long-term evolution estimated from rates of chromosomal rearrangement. Evolution. 1979;33:234–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1979.tb04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedrick PW. The establishment of chromosomal variants. Evolution. 1981;35:322–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1981.tb04890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh JB. Rate of accumulation of reproductive isolation by chromosome rearrangements. Am Nat. 1982;120:510–532. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateson W. Heredity and variation in modern lights. In: Steward AC, editor. Darwin and Modern Science. Cambridge University Press; 1909. pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobzhansky T. Genetics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Press; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller HJ. Bearing of the Drosophila work on systematics. In: Huxley J, editor. The New Systematics. Clarendon Press; 1940. pp. 185–268. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller HJ, Pontecorvo G. Recessive genes causing interspecific sterility and other disharmonies between Drosophila melanogaster and simulans. Genetics. 1942;27:157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dover GA, Flavell RB. Molecular coevolution: DNA divergence and the maintenance of function. Cell. 1984;38:622–623. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yvert G, et al. Trans-acting regulatory variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the role of transcription factors. Nature genet. 2003;35:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ng1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wray GA. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:206–216. doi: 10.1038/nrg2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittkopp PJ, Kalay G. Cis-regulatory elements: molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes underlying divergence. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castillo-Davis CI, et al. The functional genomic distribution of protein divergence in two animal phyla: coevolution, genomic conflict, and constraint. Genome Res. 2004;14:802–811. doi: 10.1101/gr.2195604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch VJ, et al. Adaptive changes in the transcription factor HoxA-11 are essential for the evolution of pregnancy in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14928–14933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802355105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedford T, Hartl DL. Optimization of gene expression by natural selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1133–1138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rifkin SA, et al. Evolution of gene expression in the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. Nat Genet. 2003;33:138–144. doi: 10.1038/ng1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemos B, et al. Rates of divergence in gene expression profiles of primates, mice, and flies: stabilizing selection and variability among functional categories. Evolution. 2005;59:126–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilad Y, et al. Natural selection on gene expression. Trends Genet. 2006;22:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.True JR, Haag ES. Developmental system drift and flexibility in evolutionary trajectories. Evol Dev. 2001;3:109–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodgins-Davis A, et al. Gene expression evolves under a House-of-Cards model of stabilizing selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:2130–2140. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingman JFC. Simple model for balance between selection and mutation. J Appl Probab. 1978;15:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turelli M. Heritable genetic variation via mutation-selection balance: Lerch’s zeta meets the abdominal bristle. Theor Popul Biol. 1984;25:138–193. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(84)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson NA, Porter AH. Rapid speciation via parallel, directional selection on regulatory genetic pathways. J Theor Biol. 2000;205:527–542. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson NA, Porter AH. Evolution of branched regulatory genetic pathways: directional selection on pleiotropic loci accelerates developmental system drift. Genetica. 2007;129:57–70. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-0033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer ME, Feldman MW. Dynamics of hybrid incompatibility in gene networks in a constant environment. Evolution. 2009;63:418–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tulchinsky AY, et al. Hybrid incompatibility arises in a sequence-based bioenergetic model of transcription factor binding. Genetics. 2014;198:1155–1166. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.168112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khatri BS, Goldstein RA. Simple biophysical model predicts faster accumulation of hybrid incompatibilities in small populations under stabilizing selection. Genetics. 2015;201:1525–1537. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.181685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tulchinsky AY, et al. Hybrid incompatibility despite pleiotropic constraint in a sequence-based bioenergetic model of transcription factor binding. Genetics. 2014;198:1645–1654. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.171397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villar D, et al. Evolution of transcription factor binding in metazoans-mechanisms and functional implications. Nature Rev Genet. 2014;15:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrg3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig MZ, et al. Evidence for stabilizing selection in a eukaryotic enhancer element. Nature. 2000;403:564–567. doi: 10.1038/35000615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher S, et al. Conservation of RET regulatory function from human to zebrafish without sequence similarity. Science. 2006;312:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1124070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hare EE, et al. Sepsid even-skipped enhancers are functionally conserved in Drosophila despite lack of sequence conservation. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowles CR, et al. Detection of regulatory variation in mouse genes. Nature genet. 2002;32:432–437. doi: 10.1038/ng992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittkopp PJ, et al. Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature. 2004;430:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature02698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porter AH, et al. Competitive binding of transcription factors drives Mendelian dominance in regulatory genetic pathways. arXiv. 2016 doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.195255. Published online June 21, 2016. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Goncalves A, et al. Extensive compensatory cis–trans regulation in the evolution of mouse gene expression. Genome res. 2012;22:2376–2384. doi: 10.1101/gr.142281.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson JH, Balakrishnan CN. Gene regulatory evolution during speciation in a songbird. G3. 2016;6:1357–1364. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.027946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McManus CJ, et al. Regulatory divergence Drosophila revealed by mRNA-seq. Genome res. 2010;20:816–825. doi: 10.1101/gr.102491.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tirosh I, et al. A yeast hybrid provides insight into the evolution of gene expression regulation. Science. 2009;324:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1169766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi X, et al. Cis-and trans-regulatory divergence between progenitor species determines gene-expression novelty in Arabidopsis allopolyploids. Nature comm. 2012;3:950. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emerson JJ, et al. Natural selection on cis and trans regulation in yeasts. Genome res. 2010;20:826–836. doi: 10.1101/gr.101576.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coolon JD, et al. Tempo and mode of regulatory evolution in Drosophila. Genome res. 2014;24:797–808. doi: 10.1101/gr.163014.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahasi K, et al. Two types of cis–trans compensation in the evolution of transcriptional regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15276–15281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mack KL, et al. Gene regulation and speciation in house mice. Genome res. 2016;26:451–461. doi: 10.1101/gr.195743.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon KL, Ruvinsky I. Tempo and mode in evolution of transcriptional regulation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Denby CM, et al. Negative feedback confers mutational robustness in yeast transcription factor regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3874–3878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116360109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bader DM, et al. Negative feedback buffers effects of regulatory variants. Mol Sys Biol. 2015;11:785. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fear JM, et al. Buffering of genetic regulatory networks in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2016 doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.188797. Published online May 18, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.116.188797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Kuo D, et al. Coevolution within a transcriptional network by compensatory trans and cis mutations. Genome res. 2010;20:1672–1678. doi: 10.1101/gr.111765.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barrière A, et al. Coevolution within and between regulatory loci can preserve promoter function despite evolutionary rate acceleration. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Landry CR, et al. Compensatory cis–trans evolution and the dysregulation of gene expression in interspecific hybrids of Drosophila. Genetics. 2005;171:1813–1822. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaefke B, et al. Inheritance of gene expression level and selective constraints on trans- and cis-regulatory changes in yeast. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2121–2133. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bell GD, et al. RNA-seq analysis of allele-specific expression, hybrid effects, and regulatory divergence in hybrids compared with their parents from natural populations. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:1309–1323. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michalak P, Noor MA. Genome-wide patterns of expression in Drosophila pure species and hybrid males. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1070–1076. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ranz JM, et al. Anomalies in the expression profile of interspecific hybrids of Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Genome Res. 2004;14:373–379. doi: 10.1101/gr.2019804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haerty W, Singh RS. Gene regulation divergence is a major contributor to the evolution of Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibilities between species of Drosophila. Mol Biol and Evol. 2006;23:1707–1714. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moehring AJ, et al. Genome-wide patterns of expression in Drosophila pure species and hybrid males. II. Examination of multiple-species hybridizations, platforms, and life cycle stages. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:137–145. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malone JH, et al. Sterility and gene expression in hybrid males of Xenopus laevis and X. muelleri. PloS one. 2007;2:e781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Good JM, et al. Widespread over-expression of the X chromosome in sterile F1 hybrid mice. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferguson J, et al. Rapid male-specific regulatory divergence and down regulation of spermatogenesis genes in Drosophila species hybrids. PLoS one. 2013;8:e61575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sundararajan V, Civetta A. Male sex interspecies divergence and down regulation of expression of spermatogenesis genes in Drosophila sterile hybrids. J Mol Evol. 2011;72:80–89. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomes S, Civetta A. Hybrid male sterility and genome-wide misexpression of male reproductive proteases. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11976. doi: 10.1038/srep11976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Turner LM, et al. Genomic networks of hybrid sterility. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Two rules of speciation. In: Otte D, Endler JA, editors. Speciation and Its Consequences. Sinauer; 1989. pp. 180–207. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson NA, Lachance J. The genetics of sex chromosomes: evolution and implications for hybrid incompatibility. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1256:E1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brawand D, et al. The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature. 2011;478:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Llopart A. The rapid evolution of X-linked male-biased gene expression and the large-X effect in Drosophila yakuba, D. santomea, and their hybrids. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:3873–3886. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meisel RP, et al. Faster-X evolution of gene expression in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dean R, et al. Positive selection underlies faster-Z evolution of gene expression in birds. Mol biol evol. 2015;64:663–674. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kayserili MA, et al. An excess of gene expression divergence on the X chromosome in Drosophila embryos: implications for the faster-X hypothesis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coolon JD, et al. Molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes contributing to accelerated divergence of gene expression on the Drosophila X chromosome. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;10:2605–2615. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oka A, Shiroishi T. Regulatory divergence of X-linked genes and hybrid male sterility in mice. Genes Genet Syst. 2014;89:99–108. doi: 10.1266/ggs.89.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Larson EL, et al. Contrasting levels of molecular evolution on the mouse X chromosome. Genetics. 2016;204:1841–57. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.186825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhattacharyya T, et al. Mechanistic basis of infertility of mouse intersubspecific hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E468–E477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219126110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ortíz-Barrientos D, et al. Gene expression divergence and the origin of hybrid dysfunctions. Genetica. 2007;129:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-0034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lenz DS, et al. Heterochronic meiotic misexpression in an interspecific yeast hybrid. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1333–1342. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gibson G, et al. Extensive sex-specific nonadditivity of gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004;167:1791–1799. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wei KHC, et al. Limited gene misregulation is exacerbated by allele-specific upregulation in lethal hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1767–1778. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campbell P, et al. Meiotic sex chromosome inactivation is disrupted in sterile hybrid male house mice. Genetics. 2013;193:819–828. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.148635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhattacharyya T, et al. X chromosome control of meiotic chromosome synapsis in mouse inter-subspecific hybrids. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Presgraves DC. The molecular evolutionary basis of species formation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nrg2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maheshwari S, Barbash DA. The genetics of hybrid incompatibilities. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:331–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brideau NJ, et al. Two Dobzhansky–Muller genes interact to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. Science. 2006;314:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1133953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thomae AW, et al. A pair of centromeric proteins mediates reproductive isolation in Drosophila species. Dev cell. 2013;27:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Satyaki PRV, et al. The Hmr and Lhr hybrid incompatibility genes suppress a broad range of heterochromatic repeats. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Watanabe TK. A gene that rescues the lethal hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Jpn J Genet. 1979;54:325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hutter P, Ashburner M. Genetic rescue of inviable hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Nature. 1987;327:331–333. doi: 10.1038/327331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barbash DA, et al. A rapidly evolving MYB-related protein causes species isolation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5302–5307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brideau NJ, Barbash DA. Functional conservation of the Drosophila hybrid incompatibility gene Lhr. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maheshwari S, Barbash DA. Cis-by-trans regulatory divergence causes the asymmetric lethal effects of an ancestral hybrid incompatibility gene. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shirata M, et al. Allelic asymmetry of the Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) gene expression in the hybrid between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: confirmation by using genetic variations of D. melanogaster. Genetica. 2014;142:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s10709-013-9752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Forejt J, Iványi P. Genetic studies on male sterility of hybrids between laboratory and wild mice (Mus musculus L) Genet Res. 1974;24:189–206. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300015214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gregorova S, et al. Sub-millimorgan map of the proximal part of mouse chromosome 17 including the hybrid sterility 1 gene. Mammalian Genome. 1996;7:107–113. doi: 10.1007/s003359900029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trachtulec Z, et al. Isolation of candidate hybrid sterility 1 genes by cDNA selection in a 1.1 megabase pair region on mouse chromosome 17. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:312–316. doi: 10.1007/s003359900430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Trachtulec Z, et al. Positional cloning of the Hybrid sterility 1 gene: fine genetic mapping and evaluation of two candidate genes. Biol J Linnean Soc. 2005;84:637–641. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Trachtulec Z, et al. Fine haplotype structure of a chromosome 17 region in the laboratory and wild mouse. Genetics. 2008;178:1777–1784. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mihola O, et al. A mouse speciation gene encodes a meiotic histone H3 methyltransferase. Science. 2009;323:373–375. doi: 10.1126/science.1163601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Storchová R, et al. Genetic analysis of X-linked hybrid sterility in the house mouse. Mamm Genome. 2004;15:515–524. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dzur-Gejdosova M, et al. Dissecting the genetic architecture of F1 hybrid sterility in house mice. Evolution. 2012;66:3321–3335. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lim FL, et al. A KRAB-related domain and a novel transcription repression domain in proteins encoded by SSX genes that are disrupted in human sarcomas. Oncogene. 1998;17:2013–2018. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Margolin JF, et al. Krüppel-associated boxes are potent transcriptional repression domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4509–4513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baudat F, et al. PRDM9 is a major determinant of meiotic recombination hotspots in humans and mice. Science. 2010;327:836–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1183439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Myers S, et al. Drive against hotspot motifs in primates implicates the PRDM9 gene in meiotic recombination. Science. 2010;327:876–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1182363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parvanov ED, et al. Prdm9 controls activation of mammalian recombination hotspots. Science. 2010;327:835–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1181495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Balcova M, et al. Hybrid sterility locus on chromosome X controls meiotic recombination rate in mouse. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Payseur BA. Genetic links between recombination and speciation. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Davies B, et al. Re-engineering the zinc fingers of PRDM9 reverses hybrid sterility in mice. Nature. 2016;530:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nature16931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Presgraves DC, et al. Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene between two species of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;423:715–719. doi: 10.1038/nature01679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tang S, Presgraves DC. Evolution of the Drosophila nuclear pore complex results in multiple hybrid incompatibilities. Science. 2009;323:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1169123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cutter AD. The polymorphic prelude to Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibilities. Trends Ecol Evolut. 2012;27:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Haldane JBS. Sex ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J Genet. 1922;12:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Coyne JA. Genetics and speciation. Nature. 1992;355:511–515. doi: 10.1038/355511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lemos B, et al. Dominance and the evolutionary accumulation of cis- and trans-effects on gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14471–14476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805160105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Orr HA. The population genetics of speciation: the evolution of hybrid incompatibilities. Genetics. 1995;139:1805–1813. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Battle A, et al. Impact of regulatory variation from RNA to protein. Science. 2015;347:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1260793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee HY, et al. Incompatibility of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes causes hybrid sterility between two yeast species. Cell. 2008;135:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ingolia NT, et al. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Artieri CG, Fraser HB. Evolution at two levels of gene expression in yeast. Genome Res. 2014;24:411–421. doi: 10.1101/gr.165522.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McManus CJ, et al. Ribosome profiling reveals post-transcriptional buffering of divergent gene expression in yeast. Genome Res. 2014;24:422–430. doi: 10.1101/gr.164996.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hou J, et al. Extensive allele-specific translational regulation in hybrid mice. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:825. doi: 10.15252/msb.156240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ghazalpour A. Comparative analysis of proteome and transcriptome variation in mouse. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Skelly DA, et al. Integrative phenomics reveals insight into the structure of phenotypic diversity in budding yeast. Genome Res. 2013;23:1496–1504. doi: 10.1101/gr.155762.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wu L, et al. Variation and genetic control of protein abundance in humans. Nature. 2013;499:79–82. doi: 10.1038/nature12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ting CT, et al. A rapidly evolving homeobox at the site of a hybrid sterility gene. Science. 1998;282:1501–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bayes JJ, Malik HS. Altered heterochromatin binding by a hybrid sterility protein in Drosophila sibling species. Science. 2009;326:1538–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1181756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liénard MA, et al. Neighboring genes for DNA-binding proteins rescue male sterility in Drosophila hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E4200–E4207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608337113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Barbash DA, et al. A rapidly evolving MYB-related protein causes species isolation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5302–5307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Phadnis N, et al. An essential cell cycle regulation gene causes hybrid inviability in Drosophila. Science. 2015;350:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Phadnis N, Orr HA. A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science. 2008;323:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1163934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cattani MV, Presgraves DC. Incompatibility between X chromosome factor and pericentric heterochromatic region causes lethality in hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Genetics. 2012;191:549–559. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.139683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sawamura K, et al. Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. II. The Zygotic hybrid rescue (Zhr) gene of D melanogaster. Genetics. 1993;133:307–313. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bomblies K, et al. Autoimmune response as a mechanism for a Dobzhansky–Muller-type incompatibility syndrome in plants. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]