Abstract

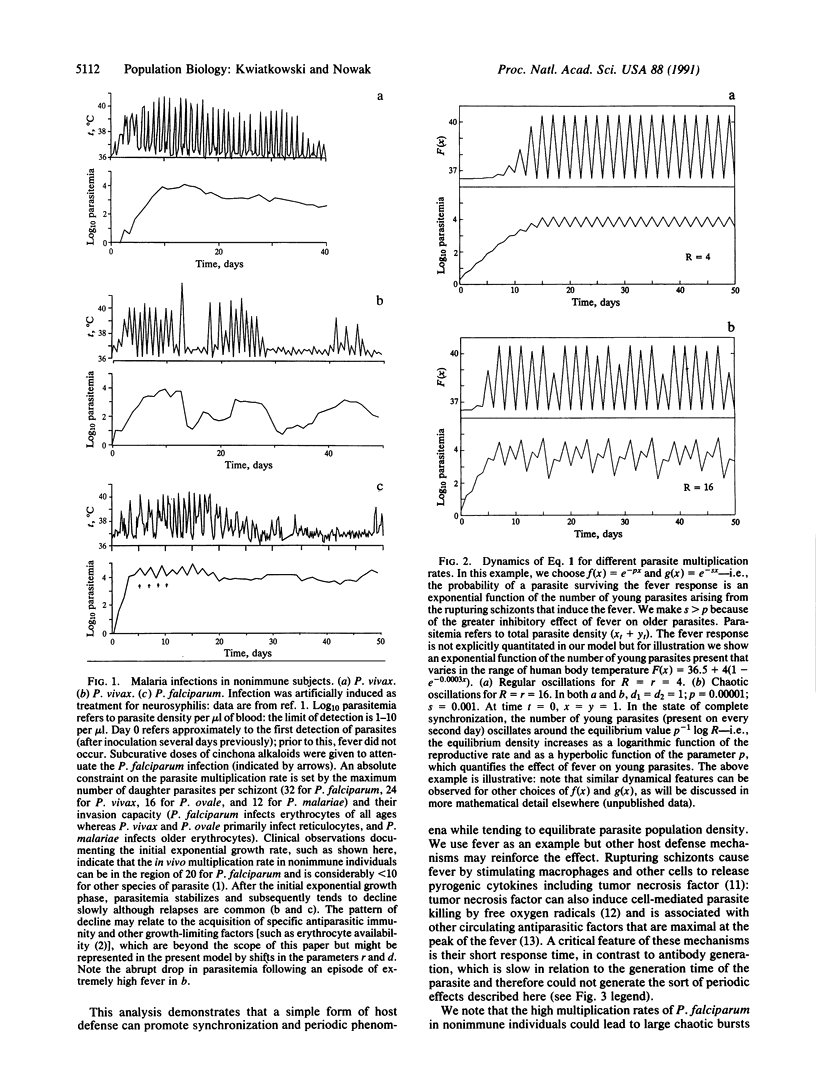

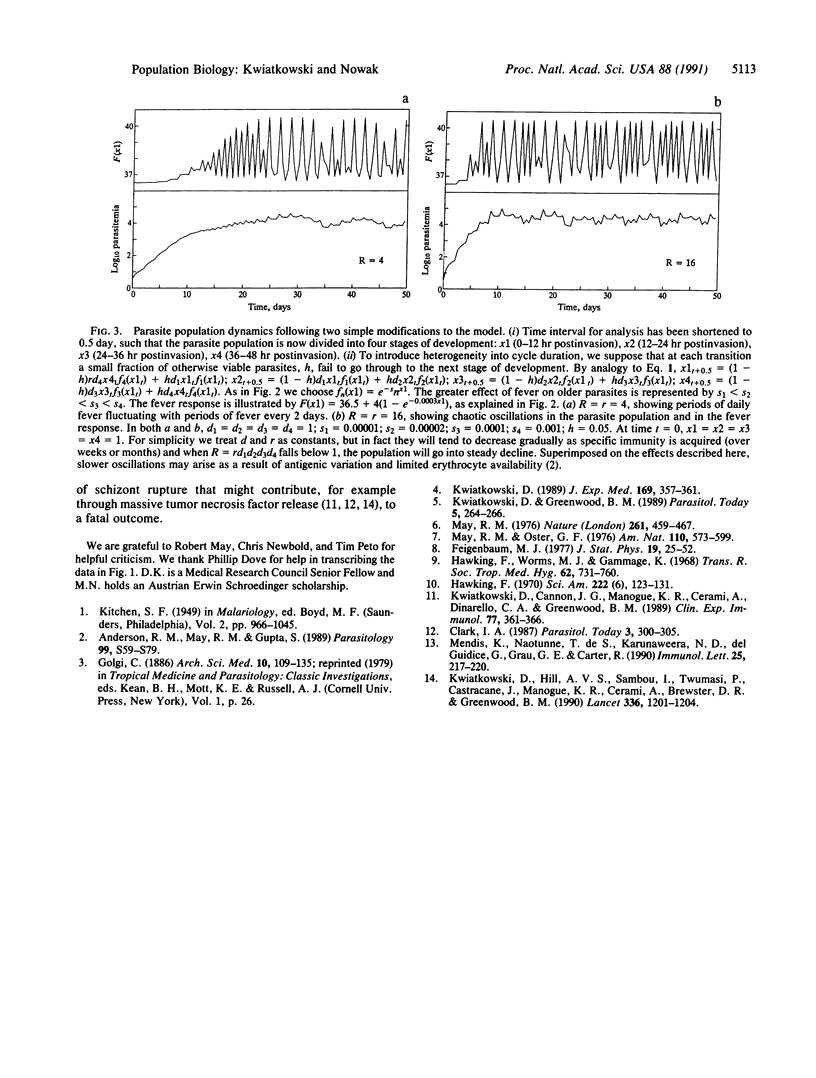

It has been recognized since ancient times that malaria fever is highly periodic but the mechanism has been poorly understood. Malaria fever is related to the parasite growth cycle in erythrocytes. After a fixed period of replication, a mature parasite (schizont) causes the infected erythrocyte to rupture, releasing progeny that quickly invade other erythrocytes. Simultaneous rupture of a large number of schizonts stimulates a host fever response. Febrile temperatures are damaging to Plasmodium falciparum, particularly in the second half of its 48-hr replicative cycle. Using a mathematical model, we show that these interactions naturally tend to generate periodic fever. The model predicts chaotic parasite population dynamics at high multiplication rates, consistent with the classical observation that P. falciparum causes less regular fever than other species of parasite.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson R. M., May R. M., Gupta S. Non-linear phenomena in host-parasite interactions. Parasitology. 1989;99 (Suppl):S59–S79. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000083426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. A. Cell-mediated immunity in protection and pathology of malaria. Parasitol Today. 1987 Oct;3(10):300–305. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawking F. The clock of the malaria parasite. Sci Am. 1970 Jun;222(6):123–131. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0670-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawking F., Worms M. J., Gammage K. 24- and 48-hour cycles of malaria parasites in the blood; their purpose, production and control. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62(6):731–765. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(68)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D., Cannon J. G., Manogue K. R., Cerami A., Dinarello C. A., Greenwood B. M. Tumour necrosis factor production in Falciparum malaria and its association with schizont rupture. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989 Sep;77(3):361–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D. Febrile temperatures can synchronize the growth of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. J Exp Med. 1989 Jan 1;169(1):357–361. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D., Greenwood B. M. Why is malaria fever periodic? A hypothesis. Parasitol Today. 1989 Aug;5(8):264–266. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(89)90261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D., Hill A. V., Sambou I., Twumasi P., Castracane J., Manogue K. R., Cerami A., Brewster D. R., Greenwood B. M. TNF concentration in fatal cerebral, non-fatal cerebral, and uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1990 Nov 17;336(8725):1201–1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May R. M. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature. 1976 Jun 10;261(5560):459–467. doi: 10.1038/261459a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis K. N., Naotunne T. D., Karunaweera N. D., Del Giudice G., Grau G. E., Carter R. Anti-parasite effects of cytokines in malaria. Immunol Lett. 1990 Aug;25(1-3):217–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]