Abstract

Purpose

Adolescent health is a major concern in LMIC but little is known about its predictors. Family disadvantage and abusive parenting may be important factors associated with adolescent psychological, behavioral and physical health outcomes. This study, based in South Africa, aimed to develop an empirically-based theoretical model of relationships between family factors such as deprivation, illness and parenting and adolescent health outcomes.

Methods

Cross-sectional data were collected in 2009–2010 from 2477 adolescents (aged 10–17) and their caregivers using stratified random sampling in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Participants reported on socio-demographics, psychological symptoms, parenting and physical health. Multivariate regressions were conducted, confirmatory factor analysis employed to identify measurement models and a structural equation model developed.

Results

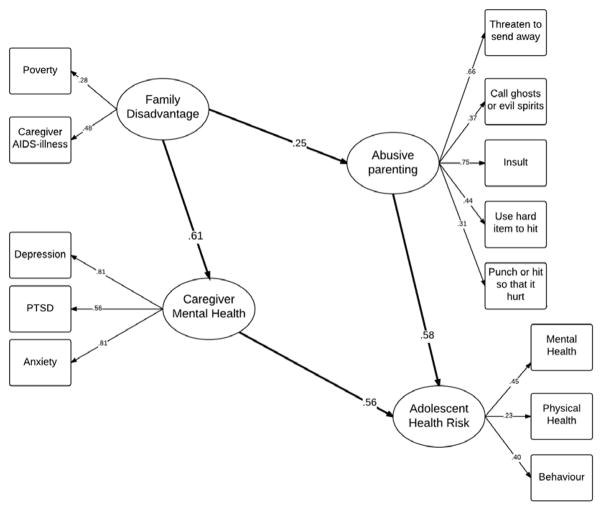

The final model demonstrated that family disadvantage (caregiver AIDS -illness and poverty) was associated with increased abusive parenting. Abusive parenting was in turn associated with higher adolescent health risks. Additionally, family disadvantage was directly associated with caregiver mental health distress which increased adolescent health risks. There was no direct effect of family disadvantage on adolescent health risks but indirect effects through caregiver mental health distress and abusive parenting were found.

Conclusions

Reducing family disadvantage and abusive parenting is essential in improving adolescent health in South Africa. Combination interventions could include poverty and violence reduction, access to health care, mental health services for caregivers and adolescents, and positive parenting support. Such combination packages can improve caregiver and child outcomes by reducing disadvantage and mitigating negative pathways from disadvantage among highly vulnerable families.

Keywords: Risk factors, parenting, adolescent health, AIDS, South Africa, adolescent abuse, mental health, adolescent behavior

Background

Each year, 1.4 million adolescents worldwide die due to violence, suicide and other health complications [1]. Adolescent mental and physical health is a major concern in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Country and region specific research is needed as factors such as unemployment and illness, and in particular large epidemics such as HIV, malaria or tuberculosis, may play bigger roles where less comprehensive welfare provisions are available. In sub-Saharan Africa, adolescents are a particular at-risk group with high rates of violence exposure, large gender and health inequalities and low life expectancy [1]. A growing body of international evidence suggests that family disadvantage such as poverty, interpersonal conflict, disability and chronic illness drive child abuse victimization [2]. Other evidence suggests that family disadvantage and child abuse are associated with major negative outcomes for adolescents in health, development and economic capacities [3]. However, research on adolescents in the region has focused primarily on risk behaviors including HIV [4].

In recent years there has been an upsurge in interest on the importance of parenting and abuse for adolescent outcomes [5], with evidence almost exclusively from high-income countries (HIC). There are many different definitions of child abuse. This paper follows the definition within the South African Children’s Act 38 (2005) which defines child abuse as ‘any form of harm or ill-treatment deliberately inflicted on a child and includes assaulting a child or inflicting any other form of deliberate injury to a child […] exposing or subjecting a child to behavior that may harm the child psychologically or emotionally”[ 6].

In North American and European studies, associations between abusive parenting and adolescent health disadvantages are well established [7]. In contrast to HIC, evidence remains very limited in LMIC. However, there is emerging high-quality evidence from sub-Saharan Africa that focuses on parenting in infancy and early childhood [8]. These studies find linkages between family disadvantage, poor parenting and childhood conduct disorders [9], suggesting the importance of testing such associations in adolescence. Research on risk factors for child abuse victimization in adolescent samples in southern Africa also identified correlations between family disadvantage and child abuse victimization [10]. In fact, family disadvantage may be one of the drivers of violence against children and adolescents.

Evidence from LMIC suggests linkages between family disadvantages and poor caregiver mental health [11]. In turn, caregiver psychological distress such as PTSD, depression and anxiety has been shown to affect parenting style and child behavior [12]. However, there is little research on pathways between these, particularly involving adolescents. New research using adolescent samples has identified pathways from household AIDS-illness to child abuse victimization mediated by poverty and disability [13]. Such research is rare and models generally investigate individual relationships between family disadvantage and abusive parenting [14] or abuse and child outcomes [15]. However, in order to understand points of potential intervention, it is essential to develop and test a theoretically and empirically relevant model of individual and family level pathways to fully understand family dynamics of disadvantage which can be used to inform the design of family-level interventions.

For adequate policy and programming to address the needs of adolescents in Southern Africa it is imperative to understand whether particular risk factors, such as family disadvantage, may be associated with abusive parenting. It is also important to establish whether abusive parenting is associated with adolescent health risks and to test pathways by which risk factors for abusive parenting may be associated with adolescent health.

Research thus far has been hampered by the limited availability of large scale data on parenting of adolescents in Southern Africa. Although some household surveys examine parenting behaviors, these have used either parents or children in each household, not data from both, and thus have analytical limitations for identifying complex pathways. For example, parents are not reliable reporters of abusive parenting, whilst adolescents are often less aware of the extent of their caregiver’s psychological distress. Consequently, it was essential to develop a model using data from both caregivers and adolescents.

This study aimed to develop a theoretical pathway model investigating hypothesized associations between hypothesized risk factors and outcomes of abusive parenting. It examines potential pathways 1) from family disadvantage to abusive parenting; 2) from abusive parenting to adolescent physical and mental health risks; and 3) from family disadvantage to adolescent health risks via caregiver mental health distress. A pathway model approach was chosen in order to allow for simultaneous analysis of multiple predictors, intervention variables and outcomes [16].

Methods

Participants and procedures

2477 adolescents aged 10–17 (53.9% female) and their primary caregiver (88.8% female) were interviewed in 2009–10 (refusal rate <0.5%) with most refusals by caregivers. Where either part of the dyad refused, the whole dyad was excluded from participation. One urban and one rural health district with high deprivation and poor health outcomes were randomly selected within KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. Within each health district, census enumeration areas were randomly sampled until sample size was reached. In each area, every household was visited and included in the study if they had a resident adolescent. One randomly-selected adolescent per household and their primary caregiver were interviewed by staff trained in working with vulnerable youth. Questionnaires and consent forms were translated and checked with back-translation into isiZulu. Utmost care was taken to ensure privacy and confidentiality during the interview process. Different interviewers were assigned to caregiver and child and questionnaires administered in a secluded spot i.e. under a tree behind the house, at the bottom of the garden or in empty classrooms after school.

Ethical protocols were approved by the review boards of the Universities of Oxford (SSD/CUREC2/09-52) and KwaZulu-Natal(HSS/0254/09) , and by the provincial Health (HRKM091/09) and Education Departments(0048/2009) . Voluntary informed written consent was obtained from adolescents and primary caregivers and refreshments and certificates of participation were given to those taking part . Confidentiality was maintained, except where participants were at risk of significant harm or requested assistance. Over the course of the study, 70 referrals were made to child protection, HIV/AIDS and health services, with follow-up support. Concerns and options were discussed with participants immediately, if requested, but otherwise after the completion of the interview, often with additional support from one of the PIs who is a child protection social worker.

Measures

Family disadvantage was measured as follows: Poverty as reported by children was measured using an index of access to the eight highest socially-perceived necessities for children in South Africa [17], showing good reliability in this sample (α =.84). Necessities included: enough clothes to remain warm and dry, soap to wash every day, three meals per day, a visit to the doctor and medicines when needed, school uniform, school equipment, school fees, and two pairs of shoes. Items were reverse coded and summed to create a poverty index (range 0–8) with higher numbers reflecting increasing levels of poverty. AIDS-unwell caregivers: Given low levels of HIV testing and HIV-status knowledge, caregiver AIDS- illness as reported by the caregiver themselves was determined using Verbal Autopsy methods, validated in previous studies of adult mortality in South Africa, (sensitivity 89%; specificity 93%) [18]. In this study, determination of HIV/AIDS required reported HIV+ status, or a conservative threshold of ≥ 3 AIDS-defining illnesses; i.e. Kaposi’s sarcoma, tuberculosis, fungal infections or shingles. Caregiver disability as reported by the caregiver was measured using two items of caregiver report on limitations of their daily physical activity and having to spend a lot of time in bed (0: no; 1: yes). Adolescent orphanhood as reported by the caregiver was defined as the death of one or both biological parents (0: no; 1: yes). Overcrowding and number of adults in the household were measured using a household map drawn by the child identifying all persons living in the house. Overcrowding was defined as a household with more than three people per room as per UN-HABITATdefinition .

Caregiver mental health distress was measured using caregiver self-report. Depression was measured using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, 20 items) [19]. The CES-D has been previously used in multiple South African populations [20]. Internal consistency was high (α=.95). Post-traumatic stress disorder was measured using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (30 item) (HTQ).The HTQ hasbeen previously validatedin South Africa [20]and showed high internal reliability (α=.94). Caregiver Anxiety was measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [21]. The BAI (21 items) has high internal consistency (α=.95) in this sample and has been validated in South Africa [22]. Each individual scale was summed to create a scale score: CES-D (range 0–60), HTQ (range 0–64) and BAI (range 0–63) with higher scores reflecting higher burden of psychological distress.

Abusive parenting in the past year as reported by adolescents was measured using five items from the UNICEF scales for national monitoring of orphans and vulnerable children [23]. Physical abuse was defined as any hitting or slapping so that it hurt, emotional abuse was insulting, shaming or threatening the adolescent. Internal consistency was good in this sample (α=.72).

Adolescent health risk was assessed on three domains of mental health, physical health, and problem behavior, all using adolescent self-report. Adolescent mental health was measured using an index created of the total sum scores of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [24] (range 0–12), the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) [25] (range 0 to 14), the Child PTSD checklist [26] (range 0–68) and the Mini International Psychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (Mini-Kid) [27] (range 0–68). The CDI has been used previously in South Africa [28] and had acceptable internal reliability in this sample (α=.65). The RCMAS has been validated in South Africa [29] and showed good internal consistency in this sample (α=.84). The PTSD checklist has also been validated in South Africa [30]and showed good internal consistency in this sample (α=.96). The Mini-Kid has also previously been used in South Africa [28] and showed good internal consistency in this sample (α=.85). Items were summed into a total score with higher scores reflecting increased mental health distress. Adolescent physical ill-health was measured as any prevalence of the five most common illnesses amongst youth: worms, flu, pneumonia, vomiting or TB in the past month and summed into an index (range 0–5) with higher scores reflecting increased number of illnesses. Adolescent behavior problems were measured using the delinquency subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [31] which has been used previously in South Africa [29] and showed acceptable internal consistency in this sample (α=.64). Items weresummed to a total score (range 0–15) with higher numbers reflecting increased conduct problems.

Socio-demographics including adolescent and caregiver age and gender and caregiver child relationship (biological parent and biological grandparent), number of adults and children in the household and presence of both vs. one parent in the household were measured using items modeled on the South African census.

Analyses

Due to the paucity of multi-stage models in the literature on parenting and child outcomes, a detailed model was not hypothesized in advance. Instead, a sequential model-building process was followed [16] in four steps. First, in order to indicate which potential predictors to include, correlations between hypothesized variables and adolescent health risks were explored. All significant variables were included in a multivariate model. Variables that were associated with adolescent health risks were included in latent constructs. Second, measurement models for each latent construct were examined using confirmatory factor analysis within the structural-equation modelling package. Third, the resulting latent constructs were all included into a model with all potential pathways, one variable with a factor loading of <.2 was dropped. Non-significant pathways were dropped and small modifications made to improve model fit, such as re-specification of covariance between control variables [16]. This resulted in a final model with four latent constructs: family disadvantage, abusive parenting, caregiver mental health distress and adolescent health risk.

Analyses were conducted in SPSS 22, and in Amos 22 using maximum likelihood estimation. As some variables were non-normally distributed, all parameters were estimated using the bootstrapping procedure with 5000 bootstrapped samples. Model fit was evaluated primarily using χ2/df. By convention, the maximum acceptable value for χ2/df is 5 [16]. Additionally RMSEA, SRMR and CFI are reported. For SRMR and RMSEA a value of 0.05 or less indicates good fit. For CFI a value of .95 or greater indicates good fit [16].

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Descriptive statistics for all socio-demographic variables and outcomes are summarizedin Table 1. M edianage was 4 2 yearsfor caregiver s and 14 yearsfor adolescents. 53.9% of adolescents and 88.9% of caregivers were female. 27.4% of caregivers were AIDS-ill and11.1% suffered from impairing disabilities . Families lacked a mean of 1.5 household necessities, with 32.1% lacking more than two basic necessities.33.6 % of adolescents were orphaned( 23.6% paternal, 15.6% maternal and5.6% double orphaned ). 66.1% adolescents were looked after by a biological parent and 18.5% by their biological grandparent, 23.1% lived with biological mother and father. Householdscontained a mean of 2.1 adults with 5.1% reporting overcrowding.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample – adolescent and caregiver report

| Adolescents (n=2477) | Caregivers (n=2477) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Percentage (n) | Median/Mean (Standard Deviation) Standard Error | Percentage (n) | Median/Mean (Standard Deviation) Standard Error | |

| Gender (female) | 53.9% (1334) | -- | 88.9% (2199) | -- |

| Age (mean) | -- | 14.00/13.57 SD 2.23 SE .05 | -- | 44.22/42.00 SD 13.88 SE .28 |

| Caregiver biological parent | 66.1% (1637) | -- | -- | -- |

| Caregiver biological grandparent | 18.5% (458) | -- | -- | -- |

| Lives with mother and father | 23.1% | |||

| Harsh parenting | ||||

| Physical and Emotional Abuse 1+/ Scale | 42.8% (1060) | 1.17 SD 1.95 SE .04 | -- | -- |

| Hypothesized family disadvantage factors | ||||

| Number of adults | -- | 2.00/2.08 SD 1.17 SE .02 | -- | -- |

| Overcrowding | 5.1% (126) | -- | -- | -- |

| Number of household members | -- | 6.00/6.00 SD 2.68 SE .05 | ||

| Poverty missing 2 or more necessities/ Scale | 32.1% (796) | 0.00/1.48 SD 2.12 SE .05 | -- | -- |

| Disability | -- | -- | 11.1% (275) | -- |

| AIDS-illness | -- | 27.4% (679) | -- | |

| Orphanhood | -- | -- | 33.6% (832) | -- |

| Hypothesized caregiver mental health factors | ||||

| Caregiver Anxiety | -- | 7.00/12.07 SD 12.83 SE .26 | ||

| Caregiver Depression | -- | -- | -- | 10.00/13.54 SD 12.31 SE .25 |

| Caregiver PTSD | -- | -- | -- | 20.00/21.16 SD 13.47 SE .27 |

| Hypothesized adolescent health risks | ||||

| Adolescent Mental Health | -- | 8.00/13.18 SD 14.28 SE .29 | -- | -- |

| Adolescent Illnesses | -- | 1.00/2.03 SD .95 SE .02 | -- | -- |

| Adolescent Behavior | -- | 0.00/0.49 SD 1.31 SE .03 | -- | -- |

42.8% of adolescents reported at least one instance of physical or emotional abuse victimization in the past year a median of one illnessin the past month.

Bivariate analysis

Using bivariate correlations, adolescent health risk was associated with caregiver is a biological parent, caregiver is a biological grandparent, caregiver age, poverty, caregiver AIDS-illness, caregiver disability, child orphanhood, abusive parenting, caregiver PTSD, anxiety and depression.

Not associated with adolescent health risk was whether the child lived with both parents, caregiver genderand overcrowding (see Appendix 1).

Appendix 1.

Correlation matrix of adolescent health risks and all hypothesized associated factors

| Adolescen t Health Risk |

Caregiver is biological parent |

Caregiver is biological grandpare nt |

Lives with father and mother |

Child age | Child gender |

Caregiver gender |

Caregiver age |

Poverty | Overcrow ding |

Caregiver AIDS- illness |

Caregiver disability |

Child orphaned |

Abusive parenting |

Caregiver PTSD |

Caregiver Depressio n |

Caregiver Anxiety |

#adults in home |

#number children in home |

#people in home |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Health Risk | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Caregiver is biological parent | −.072** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Caregiver is biological grandparent | .061** | −.666** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lives with father and mother | −.039 | .333** | −.231** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Child age | .050* | −.048* | −.054** | −.027 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Child gender | .005 | −.012 | .014 | −.047* | .056** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Caregiver gender | −.003 | −.014 | .077** | −.121** | −.009 | .064 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Caregiver age | .044* | −.287** | .592** | −.119** | .063** | .020 | .020 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | .160** | .019 | −.040* | −.081** | −.007 | −.023 | .006 | −.021 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Overcrowding | .014 | −.063** | .065** | −.048* | .039 | .008 | −.011 | .078** | .000 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Caregiver AIDS-illness | .147** | .113** | −.109** | −.033 | −.028 | .015 | −.002 | −.083** | .127** | −.023 | 1 | |||||||||

| Caregiver disability | .076** | −.089** | .166** | −.071** | .039 | −.011 | .012 | .230** | .036 | −.023 | .131** | 1 | ||||||||

| Child orphaned | .142** | −.295** | .140** | −.303** | .158** | .016 | .006 | .109** | .067 ** | .010 | .067** | .040* | 1 | |||||||

| Abusive parenting | .314** | .075** | −.014 | .033 | −.101** | .038 | .032 | −.030 | .106 ** | −.017 | .100** | .035 | −.037 | 1 | ||||||

| Caregiver PTSD | .256** | −.018 | .049* | −.032 | −.020 | .003 | .004 | .028 | .187 ** | .085** | .210** | .152** | .070** | .128** | 1 | |||||

| Caregiver Depression | .272** | −.014 | .062** | −.044* | −.001 | −.014 | .025 | .087** | .166 ** | .015 | .293** | .177** | .052* | .076** | .440** | 1 | ||||

| Caregiver Anxiety | .250** | −.057** | .143** | -.069** | -.001 | .016 | .036 | .187** | .110 ** | .037 | .215** | .188** | .066** | .012 | .340** | .675** | 1 | |||

| #adults in home | -.016 | -.064** | .122** | .133** | -.005 | -.011 | -.017 | .199** | -.097 ** | -.109** | -.092** | .051* | -.046* | -.012 | -.025 | -.033 | .013 | 1 | ||

| #number children in home | .070** | -.006 | -.022 | .011 | .006 | .033 | .090** | -.079** | .111 ** | -.178** | .035 | .006 | .006 | .076** | .137** | .031 | .029 | .206** | 1 | |

| #people in home | .049* | -.074** | .046* | .059** | .030 | .008 | .048* | .051* | .035 | -.205** | -.027 | .040* | .003 | .041* | .093** | .018 | .040* | .604** | .793** | 1 |

Regression analyses

Factors significantly associated with adolescent healthrisk in the bivariate analyses were included in a multivariate linearregression analysi s controlling for adolescent age, adolescent and caregiver genderand number of children and adults in the household (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate linear regressionmodel testing associations between adolescent health risk and hypothesized risk factors *

| Adolescent health risks

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% Confidence

Interval |

||

| Upper Bound | Lower Bound | ||

| (Constant) | −.838 | −1.192 | −.483 |

| Caregiver is biological grandparent | .013 | −.138 | .164 |

| Caregiver is biological parent | −.103 | −.210 | .003 |

| Poverty | .029 | .012 | .046 |

| Caregiver age | −.001 | −.004 | .038 |

| Caregiver AIDS-illness | .091 | .006 | .176 |

| Caregiver disability | −.045 | −.164 | .073 |

| Child orphaned | .216 | .134 | .298 |

| Abusive parenting | .145 | .126 | .163 |

| Caregiver PTSD | .008 | .005 | .011 |

| Caregiver depression | .007 | .003 | .011 |

| Caregiver anxiety | .010 | .006 | .013 |

| Child age | .029 | .013 | .045 |

| Child gender | −.028 | −.099 | .043 |

| Caregiver gender | −.075 | −.187 | .038 |

| #adults in the home | −.008 | −.040 | .024 |

| #children in the home | .014 | -.007 | .036 |

Adolescent health risk was associated with poverty, caregiver AIDS-illness, child orphanhood, abusive parenting, caregiver depression, anxiety and PTSD.

There was no significant association between adolescent health risksand overcrowding, caregiver disability, caregiver age and whether the caregiver was a biological parent or grandparent.

Measurement models

Measurement models were examined with confirmatory factor analyses to establish the latent constructs for the outcome and all hypothesized variables significantly associated with adolescent health risks. Outcome: The adolescent health risk latent construct was identified by the total scores for mental health (anxiety, depression, suicidality and post-traumatic stress), physical health and child behavior. Associated factors: The family disadvantage latent construct was identified by the total score for the poverty scale, caregiver AIDS-illness and child orphanhood. Orphanhood was then dropped from the latent construct due to alow factor loading <.20. The caregiver mental health latent construct was identified by the total score sfor depression , anxiety and post-traumatic stress.The abusive parenting latent construct was identified by the five individual types of abusive parenting.

Structural model

The following latent constructswere accordingly included in the analysis: family disadvantage associated with adolescent health risks, caregiver mental health associated with adolescent health risks, abusive parenting associated with adolescent health risks and abusive parenting associated with caregiver mental health. Non-significant pathways were removed. The final model (Figure 1) shows a double mediation from family disadvantage via abusive parentingand caregiver mental health to adolescent health risk.

Figure 1.

Pathways from family disadvantage to adolescent health outcomes via abusive parentingand caregiver mental health distress

The fit of the final model was: χ2/df=3. 33, p<.001 for CMIN 382.66, df=115; RMSEA .031, SRMR .029, CFI. 954. All fit statistics were excellent, according to the criteria in the analyses section. The final model accounted for 75% of the variance in adolescent health risks. All analyses controlled for caregiver and adolescentage and genderand number of adults and children in the household .

The following direct effectsare noteworthy. Family disadvantage was associated with increased risk for abusive parenting β = .251 (p<.001) and caregiver mental health distress β =. 614(p<.001). Abusive parentingwas associated with increased adolescent healthrisk β =. 584 (p<.001). Caregiver mental health distress was also associated with increased adolescent health risk β =. 558 (p<.001).

There wasneither a direct effect of family disadvantage on adolescent health risks nor of caregiver mental health distress on abusive parenting.

The indirect effect of family disadvantage on adolescent health risks via abusive parentingwas β =. 146 (p<.001) and β =. 343 (p<.001) via caregiver mental health. The total indirect effect of family disadvantage on adolescent health risks was β =. 489 (p<.001).

Discussion

Improving adolescent health is challenging in all societies. The empirical model developed in this study demonstrates that abusive parenting and caregiver mental health distressmediate the relationship between family disadvant age and adolescent health risks. These findings support a theory of multiple pathways between family disadvantage, parenting behaviors, parent psychosocial distress and adolescent health outcomes [32]and suggest that good adolescent health is hard to achieve for families in Southern Africa who are experiencing severe family-level challenges. In particular caregiver AIDS-illness and poverty appear to be driving caregiver mental health distress and abusive parenting, adding to previous evidence from South Africa on the impact of AIDS-illness on parenting capacity [13]. Findings also extend available literature from HICon pathways from parenting to child risk behaviors [33].

It is noteworthy that no significant direct effects were found of family disadvantage on adolescent health risks, or of caregiver mental health distress on abusive parenting. Other studies – but without the benefit of multiple paths – find strong correlations between caregiver mental health distress and abusive parenting. However, it may be that family disadvantage puts such stress on the family that this is sufficient to lead to abusive parenting and caregiver mental health which negatively affect adolescent health. Overall, findings suggest that ill health, poverty , abusive parenting and poor caregiver mental health are primarily driving the risk for adolescent health risks this South African sample.

Child orphanhood was not found to be an important contributor to family disadvantage in this study. Future research should examine if differences in caregiving arrangements for orphans and cause or length of orphanhood have a more profound impact on family disadvantage.

This study has several limitations. First, data are cross-sectional and therefore causality cannot be determined. However, in structural modelling, the attribution of causal order on plausible theoretical grounds is well-established[16] . For many of the risk pathways, reverse causality would be unlikely, e.g. adolescent health risks do not generally cause family disadvantage such as caregiver disability. However, for some pathways bi-directionality is possible, e.g. between harsh parenting and adolescent health risks. Further, it is likely that harsh parenting would have occurred as a consistent behavior over the years but this study is unable to determine whether adolescent health risks are linked to harsh parenting in early childhood or adolescence. Future research using longitudinal designs is needed to distinguish between these links. In particular the possible cyclical relationship between family disadvantage and caregiver mental health distress needs to be further investigated. Whilst there is strong evidence that people living with disabilities, HIV and in poverty have poorer mental health [34], there is also evidence that poor mental health increases risky sexual behavior [28]and that poverty is associated with AIDS -illness [35]. Second, abusive parenting was measured using child-report only and we were therefore unable to triangulate child and caregiver report of physical and emotional abuse. However, parents may be even more likely to under-report children’s violence exposure and thus child-self report is preferred to parent self-report. Third, sampling included adolescents and their primary caregiver only. The study did not include siblings or other household members and therefore cannot reflect experiences of disadvantage, abusive parenting and healthfor other youth or adultsin the household. However, measures of household and household size were utilized to give a broader insight into the family. Fourth, this study cannot draw conclusions about the role of fathers in an adolescent’s life as 89% of the sampled primary caregivers were female, although adolescents reported abuse from any caregiver within the household so fathers or other males living in the household would have been included in this. All analyses controlled for age and gender and further research could valuably investigate multiple pathways differentiated by child and caregiver gender. Fifth, this study focused solely on potential negative effects of the pathways from family disadvantage to adolescent ill health. It will be of great importance for future research to identify protective factors and protective moderators within the pathway model, and to investigate the possible role of positive parenting in this.Finally , this study was not able to identify whether abusive parentingwas carried outby the AIDS -ill caregiver or another adult in the household. It is also not able to establish whether vertical HIV transmission may drive the association between AIDS-ill caregiver and adolescent physical illness, although given that this cohort were born 7–14 years before the first introduction of pediatric antiretroviral medication in South Africa, rates of survival of perinatally-infected children would have been low.

Despite the limitations, this study also has notable strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test multiple pathways from family disadvantageto adolescent health outcomes viaparenting and caregiver mental healthin sub -Saharan Africa. Because of the lack of priortested models, this research was limi ted to empirical model-building, and future research is needed to test such a model, preferably also in other countries. The sample size was large, and the low refusal rate provided a representative sample of households with adolescents in high-deprivation areas of South Africa. Importantly, the study used a mix of caregiver and child report, in order to improve reliability of reporting.

Findings have a number of implications for policy and programming. In order to improve adolescent health in South Africa it may be essential to provide combinations of economic, health and parenting support [36]. Alleviating poverty is necessary but not sufficient: the impacts of poverty on people’s mental and physical wellbeing, particularly as these relate to parenting behaviors, also need to be addressed. Poverty alleviation programs may need to be supplemented in order to address household violence, household illness and abusive parenting, whilst parenting-focused programs may need to be designed to additionally combat severe parental psychological stress, promote parenting resilience by building self-efficacy and behavioral skills in positive parenting,and provide financial stress alleviation.

It is encouraging to note a growing evidence-base of interventions that may contribute to such combination approaches. Studies from sub-Saharan Africa show increasing success of national unconditional cash transfers as a poverty alleviation tool. Cash transfers have been shown to improve child and adolescent health and access to health care [37], and to reduce transactional and age-disparate sex in particular in combination with psychosocial care[38] .

To improve adolescent health outcomes, it is also vital to provide emotional and social support to their caregivers. Whether mental health challenges pre-date or postdate HIV infection may be of less consequence than the provision of coping interventions to ameliorate the mental health distress and its ongoing ramifications. For families with HIV-positive caregivers a number of interventions have shown to reduce adolescent and caregiver psychological distress, even over time [39]. Furthermore, testing of parenting interventions containing modules on household illness, parenting stress relief and financial pressure alleviation is currently under way with promising initial results [40].

This study clearly elaborates the pathways from family disadvantagevia abusive parentingand caregiver mental health dis tressto adolescent health risks. It can be of great value to developempirically -tested theoretical modelsin order to identify where interventions are needed and indicated. Addressing family disadvantage and supporting caregivers through suitable interventions may enhance adolescent outcomes, evenin the face of severe deprivationin South ernAfrica.

Implications and Contribution.

This study examined factors associated with health risks in South African adolescents and associations. The path model showed a double mediation from family disadvantage via abusive parenting or caregiver mental health to adolescent health risk. These findings show the need for combination interventions to support families to improve adolescent health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The research paper was made possible with support from UNICEF Office of Research- Innocenti, with resources made available from the Adolescent Well-being Research Programme, funded primarily by DFID. The views expressed are those of the authors, and do notnecessarily represent the views of UNICEF.

The research was funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council and South African National Research Foundation (RES-062-23-2068), HEARD at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the South African National Department of Social Development, the Claude Leon Foundation, the John Fell Fund, and the Nuffield Foundation (CPF/41513). Support was provided to LC and FM by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC grant agreement n°313421, the Philip Leverhulme Trust (PLP-2014-095) and the University of Oxford Impact Acceleration Account. Additional writing support was provided to CK bythe National Institute of Mental Healthof the National Institutes of Health under award number K01 MH096646, L30 MH098313. We thank Jasmina Byrne, Heidi Loening and Rachel Bray for valuable comments and suggestions and Jennifer Rabedeau for proof-reading and editing. We thank our fieldwork teams and all participants and their families.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LC and CK had responsibility for the overall study design and management. FM, LC, MO, LS, IH, CK and ADS had responsibility for conceptualizing and writing the paper. FM, MO and LC conducted the analyses for the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final version. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Strengthening the health sector response to adolescent health and development. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacMillan HL, Tanaka M, Duku E, et al. Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379:1641–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes M, et al. Transactional sex amongst AIDS-orphaned and AIDS-affected adolescents predicted by abuse and extreme poverty. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:336–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822f0d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. Promoting Positive Parenting: Preventing Violence Against Children -White paper. Denver: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Republic of South Africa. Children’s Act. Vol. 38. Cape Town: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman AB, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. The long-term sequelae of child and adolescent abuse: A longitudinal community study. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:709–23. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomlinson M, Cooper P, Murray L. The Mother-Infant Relationship and Infant Attachment in a South African Peri-Urban Settlement. Child Dev. 2005;76:1044–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avan B, Richter LM, Ramchandani PG, et al. Maternal postnatal depression and children’s growth and behaviour during the early years of life: exploring the interaction between physical and mental health. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:690–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.164848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meinck F, Cluver L, Boyes M, et al. Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2015;16:81–107. doi: 10.1177/1524838014523336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kathree T, Selohilwe OM, Bhana A, et al. Perceptions of postnatal depression and health care needs in a South African sample: the “mental” in maternal health care. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:140. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen AB, Finestone M, Eloff I, et al. The role of parenting in affecting the behavior and adaptive functioning of young children of HIV-infected mothers in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:605–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meinck F, Cluver L, Boyes M. Household illness, poverty and physical and emotional child abuse victimisation: findings from South Africa’s first prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:444. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1792-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meinck F, Cluver L, Boyes M, et al. Risk and protective factors for physical and emotional abuse victimisation amongst vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abus Rev. 2015;24:182–97. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne B. Structural Equation Modeling With Amos. 2. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes H, Wright G. Defining child poverty in South Africa using the socially perceived necessities approach. In: Minujin A, Nandy S, editors. Glob. Child Poverty Well-Being Meas. Concepts, Policy Action. Bristol: Policy Press; 2012. pp. 135–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn K, Tollman S, Garenne M, et al. Validation and application of verbal autopsies in a rural area of South Africa. Trop Med Int Heal. 2000;5:824–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myer L, Smit J, Roux LL, et al. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:147–58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards D, Steele G. Development and Validation of the Xhosa Translations of the Beck Inventories: 3. Concurrent and Convergent Validity. J Psychol Africa. 2008;18:227–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snider L, Dawes A. Psychosocial Vulnerability and Resilience Measures For National-Level Monitoring of Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children: Recommendations for Revision of the UNICEF Psychological Indicator. Cape Town: UNICEF; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. Niagra Falls, NY: Multi-health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds CR, Richmond B. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children’s anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978;6:271–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amaya-Jackson L. Child PTSD Checklist. North Carolina: Duke Treatment Service; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, et al. The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cluver L, Orkin F, Boyes M, et al. Pathways from parental AIDS to child psychological, educational and sexual risk: Developing an empirically-based interactive theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyes M, Cluver L. Performance of the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale in a sample of children and adolescents from poor urban communities in Cape Town. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2013;29:113–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyes M, Cluver L, Gardner F. Psychometric properties of the Child PTSD Checklist in a South African community sample. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Achenbach T. Child Behaviour Checklists (CBCL/2-3 and CBCL/4-18), Teacher Report Form (TRF) and Youth Self-Report (YSR) In: Rush J, First M, Blacker D, editors. Handb Psychiatr Meas. 1. Arlington, VA: The American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherr L, Cluver L, Betancourt TS, et al. Evidence of impact: health, psychological and social effects of adult HIV on children. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 3):S251–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eamonn M. Structural model of the effects of poverty on externalizing and internalizing behaviours of four to five-year-old children. Soc Work Res. 2000;24:143–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. African J AIDS Res. 2010;8:123–33. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinert J, Cluver L, Melendez-Torres G, et al. Relationships between Poverty and AIDS Illness in South Africa: An Investigation of Urban and Rural Households in KwaZulu-Natal. Glob Public Health. 2016 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1187191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter L, Naicker S. A Review of Published Literature on Supporting and Strengthening Child-Caregiver Relationships (Parenting) Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luseno WK, Singh K, Handa S, et al. A multilevel analysis of the effect of Malawi’s Social Cash Transfer Pilot Scheme on school-age children's health. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:421–32. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cluver L, Orkin F, Boyes M, et al. Cash plus care: social protection cumulatively mitigates HIV-risk behaviour among adolescents in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 3):S389–97. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein JA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lester P. Impact of Parentification on Long-Term Outcomes Among Children of Parents With HIV/AIDS. Fam Process. 2007;46:317–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cluver L, Lachman J, Ward C, et al. Development of a Parenting Support Program to Prevent Abuse of Adolescents in South Africa: Findings From a Pilot Pre-Post Study. Res Soc Work Pract. 2016 1049731516628647. [Google Scholar]