Abstract

Background

Many dialysis patients receive intensive procedures intended to prolong life at the very end of life. However, little is known about trends over time in use of these procedures. We describe temporal trends in receipt of inpatient intensive procedures during the last six months of life among patients treated with maintenance dialysis.

Study Design

Mortality follow-back study.

Setting & Participants

649,607 adult Medicare beneficiaries on maintenance dialysis who died in 2000–2012.

Predictors

Time period of death (2000–2003, 2004–2008, or 2009–2012), age at the time of death (18–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and ≥ 85 years) and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic White).

Outcome

Receipt of an inpatient intensive procedure (defined as invasive mechanical ventilation/intubation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy/jejunostomy tube insertion, enteral or parenteral nutrition, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation) during the last six months of life.

Results

Overall, 34% of cohort patients received an intensive procedure in the last six months of life, increasing from 29% in 2000 to 36% in 2012 (with 2000–2003 as the referent category, adjusted risk ratios [RRs] were 1.06 [95% CI, 1.05–1.07] and 1.10 [95% CI, 1.09–1.12] for 2004–2008 and 2009–2012, respectively). Use of intensive procedures increased more markedly over time in younger versus older patients (comparing 2009–2012 to 2000–2003, the adjusted RR was 1.18 [95% CI, 1.15–1.20] for the youngest age group, as opposed to 1.00 [95% CI, 0.96–1.04] for the oldest age group). Comparing 2009–2012 to 2000–2003, the use of intensive procedures increased more dramatically for Hispanic patients than for non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic White patients (adjusted RRs of 1.18 [95% CI, 1.14–1.22], 1.09 [95% CI, 1.07–1.11], and 1.10 [95% CI, 1.08–1.12], respectively).

Limitations

Data sources do not provide insight into reasons for observed trends in use of intensive procedures.

Conclusions

Among patients treated with maintenance dialysis, there is a trend toward more frequent use of intensive procedures at the end of life, especially in younger patients and those of Hispanic ethnicity.

Keywords: end-of-life, dialysis, intensive procedures, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), Hispanic, elderly, age differences, ethnic disparities, Medicare spending, health care costs, hospitalization, mortality follow-back

A disproportionately high percentage of Medicare spending is directed at beneficiaries approaching the end of life.1 For example, in 2011 Medicare spent approximately $170 billion, or 28% of its total budget, caring for beneficiaries in their last six months of life.2 These high levels of health care spending at the end of life largely reflect intensive inpatient-oriented patterns of care directed at treating underlying disease complications and lengthening survival.3–6 Despite increasing pressure to curb hospital length of stay and reduce re-admission, rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and use of intensive procedures (eg, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation) are becoming increasingly common among Medicare beneficiaries approaching the end of life.7–10

The Medicare End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Program provides comprehensive health insurance coverage for most patients receiving maintenance dialysis in the United States.11 Available data suggest that patterns of inpatient utilization at the end of life of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD are even more intensive than for those with cancer and some other chronic conditions.12–15 However, there is scant information about temporal trends in patterns of end-of-life care in this population and the extent to which these might parallel those described for the overall Medicare population. To address this knowledge gap, we examined temporal trends in use of inpatient intensive procedures during the last six months of life among Medicare beneficiaries treated with maintenance dialysis.

Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

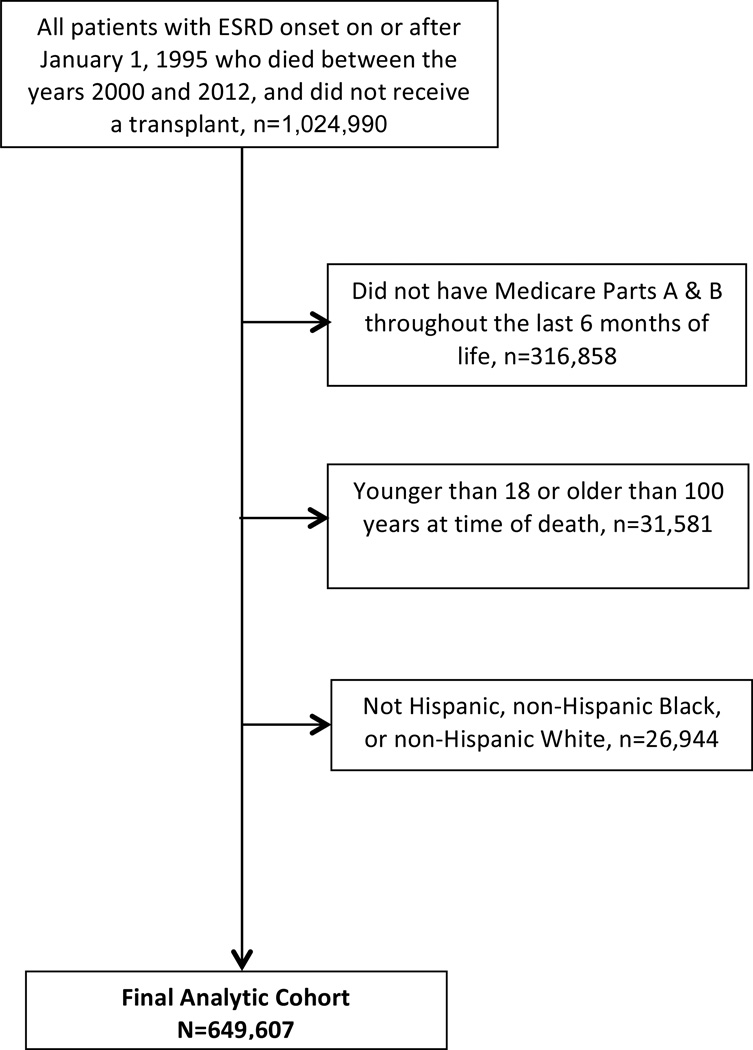

We identified all patients in the US Renal Data System (USRDS) with a first ESRD service date for maintenance dialysis in 1995 or later who died during the period January 1, 2000–December 31, 2012 and had not received a kidney transplant (n=1,024,990). We excluded patients for whom Medicare Parts A and B were not the primary payer for dialysis throughout the last six months of life (n=316,858) and those who were younger than 18 years or older than 100 years at the time of death (n=31,581). To support race/ethnicity-stratified analyses, we limited the cohort to the subset of the remaining patients who were Black, White or Hispanic (n=649,607; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart

We used information from the USRDS Patients file to ascertain age at the time of death (categorized as 18–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and ≥85 years), sex, and race/ethnicity. We used Medicare Institutional and Physician Supplier inpatient and outpatient claims to ascertain comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, emphysema, cirrhosis, dementia, cancer, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, and congestive heart failure), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan score) at a time point six months before death based on claims during the preceding one year period.16 We used the USRDS Payer History file to identify patients with dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility six months before death. We calculated the time interval between dialysis initiation and death (dialysis vintage) based on dates of death and first ESRD service for dialysis recorded in the USRDS Patients file. We used the USRDS Treatment History File to ascertain each patient’s most recent dialysis modality before death. We also included information from the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare on age, sex, race, and price-adjusted health care costs for 2012 in each patient’s hospital referral region of residence at the time of death.17

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was receipt of an inpatient intensive procedure defined using an adaptation of a previously published approach.18 Intensive procedures were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes for invasive mechanical ventilation/intubation (96.04, 96.05, 96.7×), tracheostomy (31.1, 31.21, 31.29), artificial nutrition including gastrostomy (43.2, 43.11, 43.19, 44.32) and jejunostomy (46.32) tube insertion, enteral or parenteral nutrition (96.6 and 99.15), and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (99.60, 99.63). We only considered procedures that were performed while the patient was in the hospital and within the last six months of life based on Medicare Institutional claims.18

Statistical Analysis

We described patient characteristics and use of intensive procedures during the last six months of life among patients who died in one of three sequential time periods (2000–2003, 2004–2008, and 2009–2012) using mean ±standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]) values for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. We examined the associations of age, race/ethnicity, and time period of death with receipt of an intensive procedure during the last six months of life using multivariable generalized linear models to estimate risk ratios (RRs). These analyses were adjusted for demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, Quan score, dual eligibility status, dialysis vintage, dialysis modality, and quintile of hospital referral region health care spending. To evaluate whether age differences in trends in receipt of intensive procedures might reflect differences in burden of comorbidity, we conducted a sensitivity analysis examining associations of age and time period of death with receipt of an intensive procedure stratified by quartile of Quan score. We tested for the following interactions by multiplying race/ethnicity*time period of death, race/ethnicity *age category, time period of death*age category, and race/ethnicity*age category*time period of death. Product terms were tested for statistical significance in a full model that included the main effect terms. We chose to report adjusted RRs rather than odds ratios due to the high frequency of the outcome in some subgroups.19 All analyses were conducted using Stata SE Version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Washington approved the study protocol (Human Subjects Division no. 46936). We obtained a waiver of informed consent as data were de-identified and all cohort patients were deceased at the time of our analyses. The Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee declared this study exempt from IRB review.

Results

Patient Characteristics

While the mean age of patients at the time of death varied little across time periods, the proportion of patients in the 18–59, 60–64, and ≥85 year age groups increased slightly over time. There was also a slight increase in the proportion of men and proportion of Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients as compared with non-Hispanic White patients in later as compared with earlier years. The prevalence of most comorbid conditions increased over time, but mean Quan score was stable across time periods. Median dialysis vintage (time on dialysis before death) was longest for those who died in the most recent time period. The proportion of patients with dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility increased over time. Hemodialysis was the most recent modality at the time of death for most patients during all time periods. There was little change over time in the distribution of patients across hospital referral regions with differing levels of healthcare spending (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort patients by time period of death

| Variables | Time Period of Death | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2003 (n=178,485) |

2004–2008 (n=263,792) |

2009–2012 (n=207,330) |

|

| Receipt of an intensive procedure | 31.57 (56,347) | 34.02 (89,750) | 35.74 (74,095) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y† | 70.83 ±12 | 71.02 ±13 | 12.78 ±13 |

| Age category† | |||

| 18–59 y | 16.93 (30,220) | 17.84 (47,061) | 18.21 (37,765) |

| 60–64 y | 7.88 (14,066) | 8.47 (22,354) | 9.79 (20,305) |

| 65–69 y | 13.43 (23,972) | 12.80 (33,766) | 13.28 (27,533) |

| 70–74 y | 17.41 (31,079) | 15.55 (41,012) | 14.69 (30,455) |

| 75–79 y | 19.29 (34,429) | 17.53 (46,250) | 15.41 (31,949) |

| 80–84 y | 15.04 (26,843) | 15.78 (41,628) | 14.82 (30,725) |

| ≥ 85 y | 10.02 (17,876) | 12.03 (31,721) | 13.79 (28,598) |

| Male sex | 51.80 (92,459) | 53.69 (141,619) | 55.32 (114,698) |

| Missing sex | 0.00 (1) | 0.02 (44) | 0.01(13) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 9.82 (17,522) | 10.24 (27,017) | 10.87 (22,535) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 26.96 (48,111) | 27.99 (73,824) | 27.73 (57,498) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 63.23 (112,852) | 61.77(162,951) | 61.40 (127,297) |

| Comorbid conditions* | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 65.90 (117,613) | 70.83 (186,852) | 74.55 (154,556) |

| Hypertension | 87.84 (156,779) | 91.84 (242,266) | 94.01 (194,902) |

| Dyslipidemia | 41.16 (73,460) | 57.32 (151,197) | 70.78 (146,740) |

| Emphysema | 32.76 (58,475) | 38.36 (101,201) | 41.49 (86,020) |

| Cirrhosis | 2.42 (4,327) | 3.14 (8,279) | 4.25 (8,807) |

| Dementia | 7.61 (13,574) | 9.40 (24,790) | 11.38 (23,587) |

| Cancer | 20.48 (36,547) | 21.44 (56,564) | 22.44 (46,519) |

| Coronary artery disease | 60.00 (107,092) | 63.53 (167,575) | 66.11 (137,069) |

| Stroke | 21.79 (38,888) | 23.19 (61,166) | 23.16 (48,026) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 34.69 (61,922) | 35.60 (93,897) | 38.02 (78,832) |

| Congestive heart failure | 62.79 (112,065) | 65.18 (171,928) | 66.17 (137,187) |

| Quan score | 6.81 ±3 | 7.14 ±3 | 7.49 ±3 |

| Dialysis vintage, d | 669 [245–1,296] | 839 [303–1,633] | 1008 [368–1,903] |

| Dual eligible* | 27.02 (48,219) | 29.45 (77,696) | 30.95 (64,166) |

| Most recent modality† | |||

| Hemodialysis | 92.37 (164,862) | 94.18 (248,436) | 94.58 (196,102) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6.77 (12,075) | 5.14 (13,553) | 4.75 (9,858) |

| Missing | 0.87 (1,548) | 0.68 (1,803) | 0.66 (1,370) |

| Quintile of hospital referral region health care spending† |

|||

| 1st (lowest) | 20.53 (35,932) | 20.22 (52,589) | 20.32 (41,771) |

| 2nd | 20.15 (35,261) | 20.20 (52,536) | 20.01 (41,120) |

| 3rd | 20.25 (35,435) | 19.88 (51,701) | 19.75 (40,593) |

| 4th | 19.81 (34,674) | 19.71 (51,246) | 19.60 (40,290) |

| 5th (highest) | 19.25 (33,690) | 19.98 (51,961) | 20.31 (41,745) |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as percentage (n) values for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. Group column percentage may not total 100% due to rounding.

Age, dialysis modality and hospital referral region of health care spending are presented at the time of death.

Comorbidities and dual eligibility (for Medicare-Medicaid) are ascertained at a time point six months before death.

Unadjusted Analyses

Overall, 89% of patients were admitted to the hospital at least once during the last six months of life. These patients had a median of 2 (IQR, 1–4) hospital admissions and spent a median of 20 (IQR, 8–39) days in the hospital (Table S1, available as online supplementary material). Younger patients spent more days in the hospital than older patients, and patients of non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity spent more days in the hospital than did non-Hispanic Whites. The percentage of patients admitted to the hospital during the last six months of life did not change appreciably over time, either overall or after stratification by age and race/ethnicity (Table S2). For all age and racial/ethnic groups, the median number of days spent in the hospital declined slightly over time.

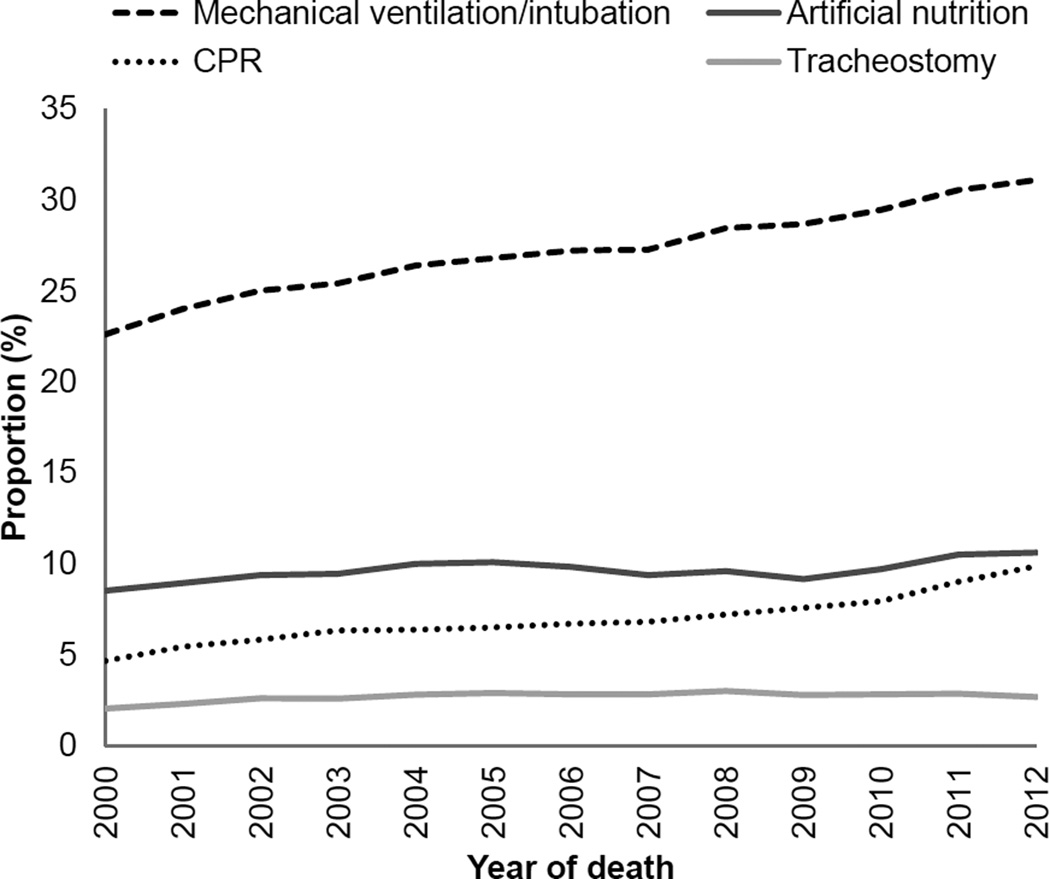

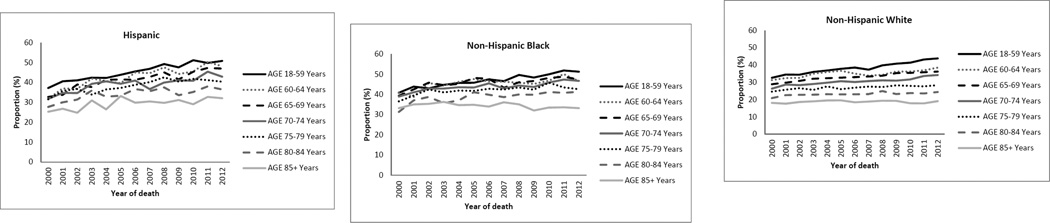

Overall, 34% of cohort patients received one or more inpatient intensive procedures during the last six months of life. Invasive mechanical ventilation/intubation was far more common than other types of intensive procedures and increased more markedly over time (Figure 2). Intensive procedures were more common in younger than in older patients, ranging from 22% in the oldest age group to 43% in the youngest age group. These procedures were most common in non-Hispanic Black patients (44%), followed by Hispanic (40%) and non-Hispanic White patients (28%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients receiving intensive procedures in the last 6 months of life: 2000–2012

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients receiving an intensive procedure in the last 6 months of life by age and race/ethnicity: 2000–2012

Over time, the percentage of patients who received an intensive procedure increased from 29% in 2000 to 36% in 2012. Use of intensive procedures increased most markedly in patients who died at younger ages, increasing from 37% to 48% in the youngest age group as compared with 21% to 22% in the oldest age group. Across racial/ethnic groups, the largest absolute increase over time occurred among Hispanics (32% to 44%) as compared with non-Hispanic Blacks (38% to 46%) and non-Hispanic Whites (25% to 31%). As for the overall cohort, the most marked increase in use of intensive procedures occurred in younger patients in analyses stratified by race/ethnicity (Figure 3, Table S3).

Adjusted Analyses

In adjusted analyses, younger patients were more likely than older patients to have received an intensive procedure during the last six months of life. This was true during all time periods and for all racial/ethnic groups (Table 2). Differences in receipt of intensive procedures in terms of age were most pronounced among non-Hispanic White patients.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations of age with receipt of an intensive procedure stratified by time period of death

| Time Period of Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Death | All years | 2000–2003 | 2004–2008 | 2009–2012 |

| All Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 1.85 (1.82, 1.88) | 1.71 (1.66, 1.77) | 1.81 (1.77, 1.86) | 2.02 (1.97, 2.07) |

| 60–64 y | 1.74 (1.71, 1.77) | 1.64 (1.58, 1.70) | 1.72 (1.67, 1.76) | 1.84 (1.79, 1.90) |

| 65–69 y | 1.66 (1.64, 1.69) | 1.56 (1.51, 1.62) | 1.64 (1.60, 1.68) | 1.79 (1.74, 1.84) |

| 70–74 y | 1.53 (1.51, 1.56) | 1.44 (1.40, 1.49) | 1.51 (1.48, 1.55) | 1.65 (1.61, 1.70) |

| 75–79 y | 1.39 (1.37, 1.42) | 1.33 (1.29, 1.38) | 1.37 (1.34, 1.41) | 1.48 (1.44, 1.52) |

| 80–84 y | 1.21 (1.19, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | 1.20 (1.17, 1.23) | 1.27 (1.24, 1.31) |

| Hispanic Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 1.60 (1.52, 1.68) | 1.62 (1.44, 1.83) | 1.59 (1.46, 1.72) | 1.62 (1.50, 1.75) |

| 60–64 y | 1.49 (1.41, 1.57) | 1.49 (1.32, 1.69) | 1.47 (1.35, 1.61) | 1.51 (1.39, 1.64) |

| 65–69 y | 1.42 (1.35, 1.50) | 1.42 (1.26, 1.60) | 1.44 (1.33, 1.57) | 1.45 (1.34, 1.57) |

| 70–74 y | 1.34 (1.27, 1.41) | 1.36 (1.20, 1.53) | 1.34 (1.23, 1.45) | 1.37 (1.26, 1.48) |

| 75–79 y | 1.30 (1.23, 1.37) | 1.34 (1.18, 1.51) | 1.31 (1.20, 1.42) | 1.30 (1.19, 1.41) |

| 80–84 y | 1.17 (1.11, 1.24) | 1.21 (1.06, 1.37) | 1.19 (1.09, 1.30) | 1.15 (1.05, 1.25) |

| Non-Hispanic Black Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 1.42 (1.38, 1.46) | 1.31 (1.24, 1.38) | 1.39 (1.33, 1.44) | 1.56 (1.49, 1.63) |

| 60–64 y | 1.36 (1.32, 1.40) | 1.27 (1.20, 1.34) | 1.35 (1.30, 1.41) | 1.46 (1.39, 1.53) |

| 65–69 y | 1.35 (1.31, 1.39) | 1.26 (1.20, 1.33) | 1.33 (1.28, 1.39) | 1.46 (1.39, 1.53) |

| 70–74 y | 1.28 (1.25, 1.32) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.27) | 1.26 (1.21, 1.32) | 1.39 (1.32, 1.46) |

| 75–79 y | 1.23 (1.20, 1.26) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.33 (1.26, 1.39) |

| 80–84 y | 1.14 (1.10, 1.17) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.30) |

| Non-Hispanic White Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 2.03 (1.98, 2.07) | 1.88 (1.80, 1.97) | 1.97 (1.91, 2.04) | 2.22 (2.15, 2.30) |

| 60–64 y | 1.87 (1.83, 1.91) | 1.80 (1.72, 1.90) | 1.83 (1.77, 1.90) | 1.97 (1.89, 2.04) |

| 65–69 y | 1.75 (1.71, 1.78) | 1.66 (1.59, 1.73) | 1.70 (1.65, 1.76) | 1.89 (1.82, 1.96) |

| 70–74 y | 1.60 (1.57, 1.63) | 1.53 (1.47, 1.60) | 1.57 (1.52, 1.62) | 1.72 (1.66, 1.78) |

| 75–79 y | 1.43 (1.40, 1.45) | 1.40 (1.34, 1.46) | 1.40 (1.36, 1.45) | 1.50 (1.45, 1.55) |

| 80–84 y | 1.23 (1.21, 1.26) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.27) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.26) | 1.27 (1.23, 1.32) |

Note: Values are given as adjusted risk ratio (95% confidence interval). Referent group for this analysis is patients aged 85 years or older at death within each time period and race/ethnic group. All analyses adjusted for sex, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, emphysema, cirrhosis, dementia, cancer, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure, Quan score, dialysis vintage, dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility, last dialysis modality, and quintile of health care spending.

In analyses with non-Hispanic White patients as the referent group, use of intensive procedures was significantly more common among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black (adjusted RRs of 1.27 [95% CI,1.25–1.29] and 1.39 [95% CI, 1.38–1.41], respectively)(Table 3). Racial/ethnic differences in receipt of intensive procedures were most pronounced among those aged 85 years or older (with non-Hispanic White patients as the reference group, adjusted RRs were 1.39 [95% CI, 1.31–1.47] and 1.76 [95% CI, 1.70, 1.83], respectively, for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients) and least pronounced for those aged 18–59 years (with non-Hispanic White patients as the reference group, adjusted RRs were 1.20 [95% CI, 1.18–1.23] and 1.20 [95% CI, 1.18–1.21], respectively, for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations of race/ethnicity with receipt of inpatient intensive procedures stratified by age group and time period of death

| Time Period of Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Death | All Years | 2000–2003 | 2004–2008 | 2009–2012 |

| Hispanic vs Non-Hispanic White Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 1.20 (1.18, 1.23) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | 1.23 (1.18, 1.27) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) |

| 60–64 y | 1.20 (1.16, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | 1.22 (1.15, 1.28) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.29) |

| 65–69 y | 1.24 (1.20, 1.28) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.28) |

| 70–74 y | 1.26 (1.22, 1.30) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.28) | 1.30 (1.23, 1.36) | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) |

| 75–79 y | 1.35 (1.31, 1.40) | 1.31 (1.23, 1.40) | 1.36 (1.30, 1.43) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.45) |

| 80–84 y | 1.34 (1.29, 1.40) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.36) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.47) | 1.36 (1.27, 1.45) |

| ≥ 85 y | 1.39 (1.31, 1.47) | 1.36 (1.20, 1.54) | 1.36 (1.24, 1.48) | 1.43 (1.32, 1.56) |

| All ages | 1.27 (1.25, 1.29) | 1.23 (1.19, 1.26) | 1.30 (1.27, 1.33) | 1.27 (1.23, 1.30) |

| Non-Hispanic Black vs Non-Hispanic White Patients | ||||

| 18–59 y | 1.20 (1.18, 1.21) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.19, 1.24) | 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) |

| 60–64 y | 1.26 (1.23, 1.29) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.32) | 1.30 (1.25, 1.35) | 1.22 (1.18, 1.27) |

| 65–69 y | 1.36 (1.33, 1.38) | 1.39 (1.34, 1.45) | 1.37 (1.33, 1.41) | 1.32 (1.28, 1.37) |

| 70–74 y | 1.40 (1.37, 1.43) | 1.40 (1.35, 1.46) | 1.41 (1.37, 1.45) | 1.38 (1.34, 1.43) |

| 75–79 y | 1.51 (1.48, 1.54) | 1.52 (1.46, 1.58) | 1.51 (1.46, 1.56) | 1.50 (1.45, 1.56) |

| 80–84 y | 1.61 (1.57, 1.65) | 1.56 (1.49, 1.64) | 1.62 (1.55, 1.68) | 1.64 (1.57, 1.72) |

| ≥ 85 y | 1.76 (1.70, 1.83) | 1.87 (1.72, 2.02) | 1.73 (1.63, 1.84) | 1.73 (1.62, 1.85) |

| All ages | 1.39 (1.38, 1.41) | 1.41 (1.38, 1.44) | 1.41 (1.39, 1.43) | 1.36 (1.34, 1.38) |

Note: Values are given as adjusted risk ratio (95% confidence interval). Referent group for this analysis is non-Hispanic White patients within each age group and time period of death. All analyses adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, emphysema, cirrhosis, dementia, cancer, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, congestive heart failure, Quan score, dialysis vintage, dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility, last dialysis modality and quintile of health care spending.

A trend toward more frequent use of intensive procedures over time persisted in adjusted analyses (with 2000–2003 as the referent group, adjusted RRs were 1.06 [95% CI, 1.05–1.07] and 1.10 [95% CI, 1.09–1.12], respectively, for 2004–2008 and 2009–2012; Table S4). In general, the upward trend in receipt of intensive procedures was more pronounced among younger than among older cohort members (in the youngest age group, with those who died in 2000–2003 as the referent group, the adjusted RR for those who died in 2009–2012 was 1.18 [95% CI, 1.15–1.20;] in the oldest age group, the corresponding adjusted RR was 1.00 [95% CI, 0.96–1.04;] Table S4). Moreover, the magnitude of differences between age groups in terms of receipt of intensive procedures increased over time (with the oldest age group in each era as the referent, the adjusted RR for the youngest age group was 1.71 [95% CI, 1.66–1.77] in 2000–2003 and 2.02 [95% CI, 1.97–2.07] in 2009–2012; Table 2). Differences between age groups in terms of receipt of intensive procedures were similar after stratification by quartile of Quan score (Table S5). For instance, in the highest quartile of Quan score, the adjusted RR for receipt of intensive procedures was 1.72 [95% CI, 1.66–1.79] for the youngest vs. oldest age group; for the lowest quartile of Quan score, the corresponding adjusted RR was 1.98 [95% CI, 1.93–1.04]. Trends over time were also consistent within each stratum of Quan score.

An upward trend in use of intensive procedures over time was more pronounced for Hispanic as compared with non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients (adjusted RRs for 2009–2012 versus 2000–2003 of 1.18 [95% CI, 1.14–1.22] as compared with 1.09 [95% CI, 1.07–1.11] and 1.10 [95% CI, 1.08–1.12], respectively; Table S4). The association of time period with receipt of intensive procedures was attenuated with increasing age for non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black patients but was similar across age groups for Hispanic patients (Table S4).

All of the interaction terms tested in a full model with the main effect terms were statistically significant (race/ethnicity*period of death, p<0.005; race/ethnicity *age category, p<0.001; time period of death*age category, p<0.001; and race/ethnicity*age category*time period of death, p<0.001).

Discussion

From 2000 through 2012, there was an upward trend in use of inpatient intensive procedures during the last six months of life among Medicare beneficiaries receiving maintenance dialysis, with the most marked increases occurring in younger patients and in those of Hispanic ethnicity.

More frequent use of intensive procedures at the end of life in younger as compared with older patients has been reported for those with other life-limiting conditions.13, 20–22 However, most studies describing patterns of end-of-life care for patients with kidney disease have either focused exclusively on older adults or did not present age-stratified results.12, 15 While life expectancy is shortest and the prevalence of frailty highest for older patients with ESRD, differences in life expectancy compared with the general population are most marked for younger dialysis patients and their prevalence of frailty is much higher than for the general population.23–25 Among members of this cohort who died young, receipt of intensive procedures was more common and increased more markedly over time compared with those who died at more advanced ages. These findings highlight the broad relevance—to younger as well as older patients with ESRD—of ongoing efforts to optimize end-of-life care for this population.26–29

Our study confirms prior reports of Black-White differences in end-of-life care patterns among patients treated with maintenance dialysis,12, 30, 31 and provides the added insight that, in contrast with many other aspects of care,32, 33 racial/ethnic differences in receipt of intensive procedures at the end of life are most pronounced at older ages. Our study also provides new information about patterns of end-of-life care among the growing number of Hispanic patients receiving maintenance dialysis.34, 35 Receipt of intensive procedures during the last six months of life among Hispanic members of this cohort was almost as common as for non-Hispanic Black patients and increased more sharply over time than for any other racial/ethnic group. Unlike other racial/ethnic groups, there was very little attenuation of this association with advancing age, with an increase in the use of intensive procedures over time observed even in very elderly Hispanic patients. These findings are consistent with observations in non–dialysis populations describing more intensive patterns of end-of-life care among Hispanics as compared with other racial/ethnic groups that have been variously attributed to differences in preferences, knowledge, language, acculturation and immigration status.36–42

There are several limitations of this study. Administrative data sources lacked detailed information about clinical context or patient preferences during the final months of life. This limited our ability to examine potential drivers of trends in use of intensive procedures and may have led to residual confounding by unmeasured factors. While it is possible that our findings may reflect the impact of changes in coding practices, we think this is unlikely because we did not observe consistent increases in the prevalence of diagnosed comorbidities, nor did we observe a uniform increase in the frequency of intensive procedures across all demographic groups over time. Also, while the mortality follow-back design represents a pragmatic and accepted approach to describing patterns of utilization at the end of life, it has inherent limitations related to differential survival probabilities among sub-groups within the population.43, 44 These concerns become less prominent as the proportion of cohort members who die during follow-up increases. Relevant to the current study, >60% of the denominator population of all Medicare beneficiaries aged 18–100 years who initiated dialysis in 1995 or later and did not receive a transplant had died by the end of follow-up for this study in 2012. Nevertheless, it is not possible to tell from our results whether an upward trend in use of intensive procedures among decedents with ESRD has occurred as part of a broader trend toward more widespread use of these procedures more generally in this population.13, 14 Finally, our study findings may not necessarily apply to racial/ethnic groups that were excluded from this study, such as American Indians, Alaska Natives, Asians, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders or those of other race.

In conclusion, from 2000–2012 there was an increase in use of inpatient intensive procedures during the last six months of life among Medicare beneficiaries treated with maintenance dialysis. These trends were most marked for younger patients and for those of Hispanic ethnicity. These findings support the broad relevance of efforts to ensure that patterns of end-of-life care fully align with the values, goals, and preferences of individual patients with ESRD of all ages and from all racial/ethnic groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: The data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US government. This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) program at the National Institutes of Health (1U01DK102150-01 to Drs. O’Hare and Kurella Tamura). Dr. Eneanya was supported in part by a mentorship grant from the NIDDK (K24-DK094872: Principal Investigator, Ravi Thadhani) and a grant from the American Society of Nephrology’s Foundation for Kidney Research Fellowship Program (Principal Investigator, Dr Eneanya). The funding sources for this study did not have a role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, or decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Aspects of this work were presented at the American Society of Nephrology’s Kidney Week, November 7, 2015, San Diego, California.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: NDE, SMH, AMO, YNH; data acquisition: AMO; data analysis/interpretation: NDE, SMH, AMO, YNH, MKT, RK, WK, MEM-R, PLH; statistical analysis: SMH; supervision or mentorship: AMO, YNH. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. NDE takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Median days spent in the hospital in last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Table S2: Percentage of patients with a hospital admission in last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Table S3: Percentage of patients who received an intensive procedure during last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Table S4: Adjusted associations of period with receipt of inpatient an intensive procedure stratified by age and race/ethnicity.

Table S5: Adjusted associations of age with receipt of an intensive procedure stratified by period and Quan score.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery

Supplementary Table S1 (PDF). Median days spent in the hospital in last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Supplementary Table S2 (PDF). Percentage of patients with a hospital admission in last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Supplementary Table S3 (PDF). Percentage of patients who received an intensive procedure during last 6 mo of life by age, race/ethnicity, and period.

Supplementary Table S4 (PDF). Adjusted associations of period with receipt of inpatient an intensive procedure stratified by age and race/ethnicity.

Supplementary Table S5 (PDF). Adjusted associations of age with receipt of an intensive procedure stratified by period and Quan score.

References

- 1.Barnato AE, McClellan MB, Kagay CR, Garber AM. Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Health services research. 2004;39:363–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasternak S. End-of-Life Care Constitutes Third Rail of U.S. Health Care Policy Debate. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiefel M, Feigenbaum P, Fisher ES. The dartmouth atlas applied to kaiser permanente: analysis of variation in care at the end of life. The Permanente journal. 2008;12:4–9. doi: 10.7812/tpp/07-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health services research. 2010;45:565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;138:288–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309:470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke CR, Feemster LC, Wiener RS, O'Neil ME, Slatore CG. Aggressiveness of intensive care use among patients with lung cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare registry. Chest. 2014;146:916–923. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Archives of internal medicine. 2011;171:196–203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman SR. Ordinary medicine: extraordinary treatments, longer lives, and where to draw the line. Duke University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medicare program; End-Stage Renal Disease prospective payment system, quality incentive program, and Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics, and Supplies. Final rule. Federal register. 2014;79:66119–66265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O'Hare AM. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172:661–663. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.268. discussion 663–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong SP, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, Hall YN, O'Hare AM. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175:1028–1035. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saeed F, Adil MM, Malik AA, Schold JD, Holley JL. Outcomes of In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Maintenance Dialysis Patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015;26:3093–3101. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachterman M, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA internal medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/publications/reports.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Development and validation of hospital "end-of-life" treatment intensity measures. Medical care. 2009;47:1098–1105. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181993191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. American journal of epidemiology. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez RA, Hevelone ND, Lopez L, Finlayson SR, Chittenden E, Cooper Z. Racial variation in the use of life-sustaining treatments among patients who die after major elective surgery. American journal of surgery. 2015;210:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong J, Xu B, Yeung HN, et al. Age disparity in palliative radiation therapy among patients with advanced cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;90:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu K, Wiener JM, Niefeld MR. End of life Medicare and Medicaid expenditures for dually eligible beneficiaries. Health care financing review. 2006;27:95–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2007;18:2960–2967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamerman D. Toward an understanding of frailty. Annals of internal medicine. 1999;130:945–950. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansen KL, Delgado C, Bao Y, Kurella Tamura M. Frailty and dialysis initiation. Seminars in dialysis. 2013;26:690–696. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R, et al. Advance Care Planning: A Qualitative Study of Dialysis Patients and Families. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2015 doi: 10.2215/CJN.07490714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010;5:195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luckett T, Sellars M, Tieman J, et al. Advance care planning for adults with CKD: a systematic integrative review. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014;63:761–770. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O'Hare AM. Geographic variation in black-white differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8:1171–1178. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06780712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2006;1:1248–1255. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00970306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Differences in control of cardiovascular disease and diabetes by race, ethnicity, and education: U.S. trends from 1999 to 2006 and effects of medicare coverage. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150:505–515. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trivedi AN, Nsa W, Hausmann LR, et al. Quality and equity of care in U.S. hospitals. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371:2298–2308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1405003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurella Tamura M, Goldstein MK, Perez-Stable EJ. Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2010;25:237–242. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, et al. US Renal Data System 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015;65:A7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrion IV, Nedjat-Haiem FR. Caregiving for older Latinos at end of life: perspectives from paid and family (unpaid) caregivers. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2013;30:183–191. doi: 10.1177/1049909112448227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley AS, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Opiniones: end-of-life care preferences and planning of older Latinos. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58:1109–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Perez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:1047–1057. e1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finley MR, Becho J, Macias RL, Wood RC, Hernandez AE, Espino DV. Attitudes regarding the use of ventilator support given a supposed terminal condition among community-dwelling Mexican American and non-Hispanic white older adults: a pilot study. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:852564. doi: 10.1100/2012/852564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;154:235–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guadagnolo BA, Liao KP, Giordano SH, Elting LS, Shih YC. Variation in Intensity and Costs of Care by Payer and Race for Patients Dying of Cancer in Texas: An Analysis of Registry-linked Medicaid, Medicare, and Dually Eligible Claims Data. Medical care. 2015;53:591–598. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:2765–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teno JM, Mor V. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1591-a. author reply 1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.