Abstract

Research informed by individuals’ lived experiences is a critical component of participatory research and nursing interventions for health promotion. Yet, few examples of participatory research in primary care settings with adolescents and young adults exist, especially with respect to their sexual health and health-risk behaviors. Therefore, we implemented a validated patient-centered clinical assessment tool to improve the quality of communication between youth patients and providers, sexual risk assessment, and youths’ health risk perception in order to promote sexual health and reduce health-risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults in three community health clinic settings, consistent with national recommendations as best practices in adolescent healthcare. We describe guiding principles, benefits, challenges, and lessons learned from our experience. Improving clinical translation of participatory research, requires consideration of the needs and desires of key stakeholders (e.g., providers, patients, and researchers), while retaining flexibility to successfully navigate imperfect, real-world conditions.

Keywords: patient-centered, participatory research, youth, sexual health, health risk behaviors

Community-engaged research can improve the nation’s healthcare by bridging practice and research (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Dulmus & Cristalli, 2012; Faridi, Grunbaum, Gray, Franks, & Simoes, 2007; Savage et al., 2006), while also yielding quality data (Bay-Cheng, 2009), and positive gains for stakeholders (Bay-Cheng, 2009; Dulmus & Cristalli, 2012; Pew Partnership for Civic Change, 2003) and communities (Koné et al., 2000). Over time, the standards for community-engaged research have evolved to ensure that all stakeholders are represented from the outset (; Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centerd Outcomes Research Institute [PCORI], 2013). Stakeholders can be members of a research team, clinic staff, clinicians, and/or patients. Several research approaches can be categorized as community-engaged, such as participatory, community-based participatory, and practice-based research (Nation, Bess, Voight, Perkins, & Juarez, 2011). All share common themes: partnerships between stakeholders; shared power; commitments to long-term partnerships and/or relationships; and research that is conducted in collaboration with participants, communities, or patients (Viswantathan et al., 2003). Community-engaged research has the potential to inform translational science in ways that other approaches cannot. By involving a diverse group of stakeholders working together to address health disparities, community-engaged research can inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of interventions within the healthcare setting (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010) and increase access to healthcare directly addressing the needs of patients (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). This approach is in line with national imperatives calling for community-engaged and patient-centered approaches in clinical and healthcare settings that emphasize patient-provider communication, patient participation in healthcare decisions, and healthcare that integrates individuals’ values and preferences (Institute of Medicine, 2001, 2008, 2012).

Strengths of Participatory Research Approaches

Benefits of community-engaged and participatory research efforts are multidirectional; they are not reserved for patients, clinic teams, or researchers alone. This approach may allow patients to receive increased access to evidence-based practices (Dulmus & Critalli, 2012), share a greater sense of equality than with traditional approaches (Bay-Cheng, 2009; Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010), and feel that clinical recommendations are culturally responsive (Savage et al., 2006). Clinic stakeholders may improve their services, engage new patients, and form alliances with patients that emphasize and support their health (Pew Partnership for Civic Change, 2003). Research stakeholders may form direct relationships with patients and providers (Rhodes et al., 2010) and more effectively disseminate findings in novel ways (Faridi et al., 2007). Stakeholder partnerships allow for a “blending of lived experiences with sound science” leading to a richer understanding of the phenomenon under investigation and informing interventions (Rhodes et al., 2010, p.174).

The benefits of community-engaged research are not automatic nor are they without challenges (Koné et al., 2000). For example, original proposals may need to change due to funding, fluctuations in the interest of collaborators, and/or attitudes regarding research in healthcare settings (A. L. Miller et al., 2008). Despite potential challenges to strict adherence to the official tenets of community-engaged research, one that is critical is adaptability—the ability to adjust to the needs and interests of stakeholders. Forming partnerships across stakeholders requires effort, genuine respect, cultural acceptance and awareness, and a departure from the notion that research and practice are at odds (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; A. L. Miller et al., 2008). There are likely instrumental challenges related to time and organizational infrastructure/culture of the clinic setting. Conducting sound community-engaged research is time-intensive; forming trusting working relationships between stakeholders over the development and course of a study requires determination and flexibility in addition to typical service provision and utilization (Israel et al., 2006). When stakeholders can collaboratively develop a plan of implementation, the process has a greater chance of long-term sustainability (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Dulmus & Cristalli, 2012).

Context of the Current Study

Standard recommendations for youth preventive healthcare guidelines include sexual risk screening (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2008; Elster & Kuznets, 1994; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). The current study was a part of a larger participatory-based randomized control trial (RCT; see Table 1). The primary aim of this larger study was to evaluate the possible differential impact of the Sexual Risk Event History Calendar (SREHC) to a “gold standard” assessment, the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS), in relation to youths’ sexual attitudes, intentions, and risk behaviors. The Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior and tenets of participatory research guided this RCT within university and community health clinics in the Midwest. Patients completed a pre-intervention survey; met with a provider who used either the SREHC or GAPS assessment (the randomized control component); and completed surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months. Patients could give feedback on the SREHC to their provider or research stakeholders during the study at any time, or in focus groups after study completion. Healthcare providers offered feedback on their experience using the tools during or at the end of the study through surveys and individual interviews. Nine providers across these clinics and 181 patients ranging in age from 15-25 years old comprised the provider and patient stakeholder groups. The SREHC had a positive impact in relation to sexual health intentions (e.g., likelihood for having sex; likelihood for using condoms), and differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors were observed related to individual factors (Munro-Kramer et al., in progress).

Table 1.

Guiding Principles of Patient-Centered Participatory-Based Research

| Guiding Principles | Engagement Plan | Real World Execution and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Stakeholders are defined based on the research and in broad terms. |

In our studies we include patients, providers, and clinic administrative and staff teams. |

This study was able to incorporate patients, healthcare providers, clinic staff, and administration as stakeholders. |

| 2. Researchers are both part of the traditional research teams and participants in the clinic settings where we conduct our research. |

Research team includes youth patients, providers, and a Project Manager that has regular interaction with all stakeholders. These team members function as an advisory board where they incorporate patient partner viewpoints at all research team meetings. |

The Project Manager was integral to maintaining a participatory research-based approach. She was welcomed into the participating clinics with open arms as a part of the “staff” to improve health. She conversed with stakeholders regularly and relayed their thoughts to research stakeholders. For example: Project Manager: “What would be helpful?” Physician: “Have them fill out something prior to them seeing us because we have a very limited time to discuss those things in a physical exam kind of environment and so if we knew what they were interested in, that could help kind of guide the conversation to what they’re open to talking about.” |

| 3. Stakeholders are included in all aspects of the research process. |

Stakeholders help construct research questions, methods, and outcomes they feel are important. This includes monitoring and adjusting study procedures, dissemination, and implementation of results. Provider stakeholders serve as site Principal Investigators (PIs)/liaisons; active research stakeholders; and participants in focus groups, interviews, and meetings. |

The clinic stakeholders who developed the study questions and design withdrew after funding and Institutional Review Board (IRB) was granted. The alternate clinic stakeholders engaged in this study were comparable to the original stakeholders. They participated in monitoring and adjusting study procedures, implementation, and dissemination of results. One physician noted the following about implementation: Physician: “A lot of stuff the adolescent will not tell you. If they are out doing drugs, they are not going to tell you. Even if you ask them, “do you do drugs?” I mean I ask a whole lot of people every day, “do you do drugs, do you do this?” The answer is no, no, no, no, no. Something about knowing they do a whole lot of things. People, people, I’m not going to say tend to lie, but maybe they, because the doctor is an authority figure, they would just want to please the doctor. So, they give them the answer they would like to hear. See, that’s the thing. With this tool right there, this will help us big time to discover things about adolescents that are kinda hidden, in a way hidden, and then can elaborate and help with that.” |

| 4. Stakeholders are included with minimal burden to them. |

Participation from multiple locations is made possible through distance technology (e.g., conference calls, Skype) and relaying of information through different stakeholders. Researchers work within the structure of the clinic to reduce demands on stakeholders. This involves researchers being actively engaged in the day-to-day basis as needed. |

Throughout this research project, clinic stakeholders were actively involved via regular communication either directly with research stakeholders, or with the Project Manager on a weekly basis. This project did not incorporate distance technology, because clinic stakeholders enjoyed participating and did not see it as burdensome. One healthcare practitioner said, “Thank you for including me in your study, best of wishes to you!” |

| 5. Stakeholders recognize that they determine changes in the research, dissemination, and implementation through their input. |

The interventional tool used in the study has been designed and revised based on a qualitative model with ongoing input collaborative stakeholders. Transparency is upheld through constant multidirectional communication including updated reports, tools, manuscripts, and presentations based on changes or recommendations they provide. |

This principle was upheld in our study. Throughout the course of the research process, stakeholders gave input on changes to the research process, how they wanted results disseminated to them (i.e., via face-to-face meetings), and discussed future implementation strategies. Provider stakeholders also found that patient stakeholders were honest about their use of the history tools and participation in the study. |

| 6. Stakeholders are included in dissemination and implementation of outcomes. |

The partnership between stakeholders is based on mutual respect and a sense of co-learning. This attitude facilitates the inclusion of stakeholder recommendations in the dissemination and implementation of outcomes. |

This principle was also upheld as research stakeholders had ongoing communication with clinic stakeholders via visits and presentations. Additionally, clinic stakeholders used the results from this study and disseminated them to their patients and communities. One healthcare provider noted, “So, I wish we could make appointments for this (the interventional history tool)… Because I see that there are these kids, sometimes away from their parents for the very first time and they need a lot of direction and they don’t really know how to get it. And so, I would love to see some sort of mechanism to have appointments for that. So, we can continue, kind of the process.” |

| 7. Stakeholders engage in long term research and implementation relationships. |

Partnerships between stakeholders are initiated prior to the research plan being prepared for grant submission. At this time all parties commit to participate for the duration of the study. These relationships are maintained by interacting weekly on the study progress, data collection, analysis, and next steps. This process has resulted in a long-term relationship with one university health clinic that has been on-going for over three years. |

Throughout the course of this study, research stakeholders established long-term relationships with clinic stakeholders who helped prepare and submit a grant submission to continue this project. Unfortunately, this grant was not funded and the PI relocated to a new location. However, members of the research team have remained involved with the clinic sites for related research studies. Clinic stakeholders also described their desire to remain involved. Healthcare Provider: “And I’d like to continue and maybe do another study. Do you guys have more, another study coming up with more patients?” Patient: “I would definitely be willing to participate. When I was younger one of my jobs was in a market research setting and I like this kind of stuff so I know it actually is for a purpose and what you guys are doing is good work…” |

Assessment Tool: Sexual Risk Event History Calendar

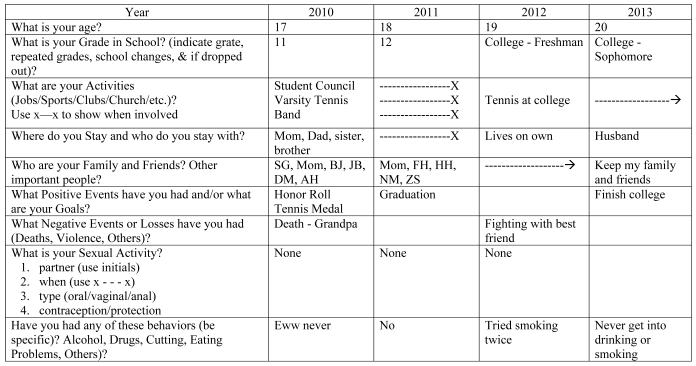

Assessing the needs of individuals and available resources in a community are the first steps to providing patient-centered clinic-based sexual health services (Kirby, 2007) that are relevant, accessible, and appropriate for youth (McIntyre, Williams, & Peattie, 2002). The SREHC was developed through extensive community-based pilot studies. Namely, the SREHC was developed and modified with culturally and racially diverse youth (i.e., African American, Latino, and White) on a national level in order to design a person-centered assessment tool to improve youths’ awareness of their own health risk behaviors, while simultaneously enhancing patient-provider communication. This was done with the SREHC using a visual representation of one’s sexual health history within life context, which is broken down into general categories (see Figure 1; Martyn et al., 2009; 2013). Written at a 5th grade reading level, the SREHC utilizes an event history calendar format based on autobiographical memory concepts to improve data quality, retrieval cues, cognitive abilities, and conversational engagement to capture social and health risk behaviors across a four-year timespan (current year, past two years, and future; Belli, Stafford, & Chow, 2004). The SREHC also has open-ended questions, which prior participants felt made it culturally appropriate to a more diverse group based on education, socioeconomic status, sexual identity, ethnicity, race, and location (Martyn & Martin, 2003; Martyn, Darling-Fisher, Smrtka, Fernandez, & Martyn, 2006).

Figure 1. Sample SREHC: Female with Minimal to No Risk Behaviors.

Legend: X ---- X = Duration, beginning and end points; X --➔ = Duration, beginning and continuing points; “SG,” “ZS,” etc = initials (pseudonyms) for a friend, family member, or important person.

Copyright: The Regents of the University of Michigan, 2009. Used with permission.

Thus, the SREHC, by design, reduces the power differential across stakeholders. This is in line with calls from the Institute of Medicine (2001) and empirical evidence suggesting that patient-centered approaches for adolescent healthcare are more effective, better received by patients, and more cost effective (Epstein, Fiscella, Lesser, & Stange, 2010; Pew Partnership for Civic Change, 2003; Stacey et al., 2014). Prior work on the SREHC indicated that it generates quality data about activities, health behaviors, events, and transitions occurring over long time periods with youth from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds (Saftner, Martyn, Momper, Kane Low, & Loveland-Cherry, 2014). The SREHC also has empirical effectiveness as a clinical tool in facilitating sexual risk assessment, improving communication amongst patients and providers, and increasing youths’ risk perception by focusing on the link between sexual risk behaviors with other risk behaviors (Martyn & Martin 2003; Martyn Reifsnider, & Murray, 2006; Martyn et al., 2009; Martyn et al., 2013).

Purpose

Nurses are frontline providers within the healthcare system and their research often involves patients in the planning, evaluation, and dissemination process. It is imperative that nursing researchers are able to articulate their use of participatory research-based approaches and their contributions to science (Polit & Beck, 2012). The current paper details the process (e.g., methods, challenges, benefits) of utilizing a patient-centered participatory research approach in three Midwest community clinics to inform similar research conducted on youths’ overall and sexual health. Throughout this study and in this paper we consider all of those involved in the planning, implementation, participation, and dissemination of the project as “stakeholders.” In general, these individuals represent three different groups: clinic stakeholders (i.e., nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physicians, administrators, and staff associated with clinic operations), patient stakeholders (i.e., patients seeking care at respective clinics), and research stakeholders (i.e., members of the research team; PCORI, 2013). It is important to note that there is overlap of roles and groups to which individuals may belong—one person may have had multiple roles. Our goal was to collaborate with clinic and patient stakeholders in order to improve the quality of care youth received regarding their sexual and health risk behaviors utilizing the SREHC.

Methods

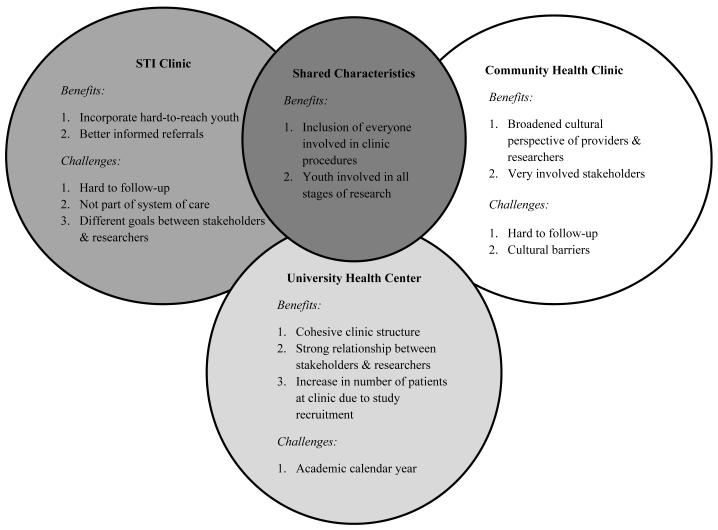

The original team of stakeholders for this study (and the larger study: participatory research-based RCT) was comprised of: (a) members of the community including students and young adults who were patients of university health clinics; (b) community clinicians with prior involvement in pilot trials of the SREHC; (c) nursing and social work researchers; and (d) four different clinics within the same healthcare system. This team worked together to identify the needs of various stakeholders when designing the study. However, after our proposal was accepted and funded, the original clinics discontinued their participation due to administrative changes. Changes to the stakeholder group occurred with the introduction of three new clinic sites; however, the rest of the stakeholder group remained the same. The new clinics included a county sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic, a community-based health clinic in an Arab-American community, and a university health center. This type of adaptation among the stakeholders is acknowledged and accepted by PCORI as a consequence of doing participatory research in the real world (PCORI, 2013). A Certificate of Confidentiality and approval from the University of Michigan Health Science Behavioral Science institutional review board was obtained, as well as approval from the institutional review boards of each clinic site.

Although adjustments were made to specific research questions with the introduction of new stakeholders, the intent of the study and majority of the stakeholder team did not change. One way that these imperfect conditions were addressed and remained in line with the guidelines of participatory-based research was that numerous IRB amendments were submitted over the course of this study to meet clinic and patient stakeholder needs. For example, writing in the role of a community member/clinic stakeholder into our IRB document. She was an invaluable additional to our team serving as a gatekeeper and broker at the Arab-American community health clinic; she provided assistance with outreach and recruitment (e.g., recruiting at community health fairs), and connecting with patients throughout the study to help with retention. The Project Manager, Ms. Felicetti, was another key team member who played a critical role as a broker with the original and new sites. Team collaboration was highlighted in various ways throughout the project, culminating when the University Clinic presented the Gold Medallion Award to our Project Manager due to her seamless interaction with all stakeholders. Descriptions of our varied experiences within each clinic illustrate our approach to participatory research (i.e., process, benefits, and challenges; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Benefits and Challenges of Using a Participatory Research-Based Approach in Three Clinic Sites

Participating Clinics and Procedures

All clinic sites shared certain qualities: (a) employing two or more providers (i.e., nurse practitioners and/or physicians) with at least one-year of experience in adolescent primary healthcare; (b) providing healthcare services to youth ages 15 to 27 to accommodate stakeholders’ interest in the health and well-being of both adolescents and young adults; (c) serving English speaking patients; and (d) participation for the full duration of the study. Each clinic wanted to gain experience to more comprehensive youth health assessments through their participation in this project. As partners in this process they aided in clinic specific procedure development, including assessment tool adjustments and implementation. The Project Manager facilitated and synthesized feedback from clinic and patient stakeholders into recommended changes (e.g., IRB amendments, meetings to troubleshoot site specific challenges).

In addition, modifications, input/feedback, and/or updates to the SREHC could be, and were, made throughout the course of the study. For example, when a patient filled out the SREHC in the waiting room, they could give the healthcare provider feedback during their appointment, or they could ask the Project Manager and/or other research stakeholders a question or offer suggestions. Implementing the SREHC with a patient allowed the healthcare provider: the opportunity to ask questions based on the information written on the SREHC; determine when to probe for more information; or identify ways in which the SREHC would work better in the context of the healthcare appointment and relay that information to other study stakeholders for real-time updates. The study design included scheduled check-in points and flexibility for all stakeholders to provide feedback throughout the study. Therefore, data was collected at the scheduled follow-up times, as well as throughout the course of the study. Data included surveys measures at set time points (quantitative data), focus groups occurring at the end of the study (audio recorded qualitative data that was transcribed), and spontaneous feedback during the study (qualitative data recorded through detailed notes, stored with research stakeholders).

Dissemination is a critical methodological component of research, especially participatory research. This includes empirical findings from a study as well as the experiences that stakeholders had throughout the process to guide others (Morrison-Beedy, Passmore, & Baker, 2016). In our case, stakeholders from each site were interested in the overall findings of the larger study just as much as we were interested in their experience with the SREHC. To this end, research stakeholders gave presentations of the findings (outcome and process findings) to stakeholders at the university and community health clinics. In addition, stakeholders from the STI clinic received the same presentation, however, this was given at the research stakeholders’ home university as these clinic stakeholders had dual roles with the university and at the STI clinic. Presentations were dynamic, where all stakeholders shared their experiences and lessons learned; thus, another forum existed for mutual learning and participation across stakeholders.

County health department STI clinic

The county health department STI clinic provides services to transient at-risk youth. Specifically, patient stakeholders at this site (n = 18) were on average about 19 years old (SD = 2.3), predominantly male (59%), students (83%), single (83%), and Black/African American (89%) and non-Hispanic (89%). This clinic is open one to two evenings a week, and staffed by two nurse practitioners and HIV counselors whose focus is on one-time HIV/STI testing and community referrals. The structure of this clinic greatly impacted the level of involvement of clinic stakeholders; compared to the other sites, these clinic stakeholders were less involved in the research process. Yet, two providers at this site were faculty members at the research stakeholders’ university, and two research stakeholders were clinicians at other clinics that served similar populations of youth seeking services at this STI clinic. Thus, these providers were available for consult at the University if not at the clinic, and the Project Manager met with these clinic stakeholders regularly throughout the study.

Community health clinic

The community health clinic is a large inclusive health center in a predominantly Arab-American community in the Midwest that provides a variety of health promotion and healthcare programs. Overall, patient stakeholders at this community health clinic (n = 66) were on average, 18 years old (SD = 3.0), split almost equally by biological sex (48.5% male), and a majority were students (86%), employed (92%), single (80%), White (88%), and Arab (95.5%). There was one physician and one nurse practitioner, who was replaced by another physician during this project. Two of the three providers were Arab-American. Collaboration between all stakeholders was prominent at this site; as noted, an amendment to the IRB was made to include a key broker from the clinic who aided in recruitment, scheduling, and retention.

University health center

Located at a large public Midwestern university, this student-centered healthcare clinic provided general healthcare, on-site STI testing, free counseling sessions, and specialized referrals. Student patient stakeholders (n = 102) were on average, 20 years old (SD = 2.4), mostly women (65%), not working (91%), single (60%), White, (60%) and non-Hispanic (90%). At this facility there was one physician and two nurse practitioners.

Results: Benefits and Challenges of using a Participatory Research-Based Framework

There were general benefits and challenges in using a patient-centered participatory research-based approach. A goal and shared benefit for all stakeholders was that patient-centered communication changed and improved as reported by patient and clinic stakeholders across the different sites. This is similar to findings from previous pilot studies using the SREHC (Martyn et al., 2013). Providers gained a better understanding of the types of questions they could ask youth in order to increase the effectiveness and relevance of care. Provider stakeholders in this study were better oriented to patient (person)-centered techniques, which influenced how they interacted with patients, which allowed patients to share more information with their providers. This was a consistent them in patient and provider stakeholder feedback and in focus groups.

As described in the methods, the largest challenge of this study was the need to replace the original four health clinics that were part of the initial study design. This was reconciled within guidelines set forth by PCORI (2013); however, it was not an ideal situation for pure participatory research. Other challenges were related to the patient population, as youth are often transient with changing jobs, residences, and phone numbers. Although there were certain shared criteria for collaborating clinics and pre-defined protocol procedures (e.g., three contact attempts before an individual was no longer eligible), recruitment and retention procedures were unique to each site based on specific needs and clinic structure. Some challenges may have been avoided if all clinic and patient stakeholders had been a part of the original planning process; however, participatory-based research in the real world often presents unforeseeable barriers that stakeholders need to manage effectively (Morrison-Beedy et al., 2016).

County health department STI clinic

Recruitment occurred on-site at the time of a patient’s visit at the STI clinic and via a single flyer placed in the Women, Infants, and Children program area. Intent of services (i.e., one time STI/HIV testing and counseling without the expectation of return visits from patients), limited hours, patient stakeholder demographics, and high turnover of office staff seemed to hamper recruitment at this site. Other challenges that clinic stakeholders noted were the perception of stigma or embarrassment among patients for accessing HIV/STI testing and services and cultural and individual characteristics of patient stakeholders. For example, youth seeking STI services presented with high-risk behaviors and life stressors (e.g., homelessness, abuse, poverty, substance use) that increase vulnerability on a variety of levels, including exploitation, health status, and access (i.e., lack of) to healthcare resources (Ahrens et al., 2010; Koball et al., 2011; Leslie et al., 2010). Also, administrative clinic stakeholders at this site did not develop an active partnership with other stakeholders—a core component of patient-centered participatory research. This was in contrast to the other clinics where administrative clinic stakeholders acted as brokers and liaisons between all stakeholders in the study, resulting in more successful recruitment and retention (see Table 2). These factors may explain why only 18 participants were recruited from this site and 11 completed the follow-up.

Table 2.

Enrollment and Retention Statistics all Clinics

| Retention % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic* | Enrolled (n) | 3-month | 6-month | 12-month |

| STI Clinic | 18 | 83.3% (15) | 66.7% (12) | 61.1% (11) |

| Community health clinic |

66 | 80.3% (53) | 75.8% (50) | 63.6% (42) |

| University health clinic |

102 | 99.0% (101) | 94.1% (96) | 84.3% (86) |

| Totals | 186 | 90.9% (169) | 84.9% (158) | 74.7% (139) |

All participant enrollment and retention took place over a two-year time period

These challenges highlight the importance and advantage of engaging patient stakeholders from the outset of a project. Patients utilizing this type of clinic are in need of comprehensive health services, perhaps more so than those privy to annual preventive services. Qualitative data from this study and similar research (Bay-Cheng, 2009) suggest that completing a comprehensive history tool may provide at-risk youth with their first opportunity to discuss health related questions in a way that considers their desires, needs, and experiences, thus creating an ideal methodological match between the needs of patients at this type of clinic and patient-centered participatory research. For example, at follow-up youths received additional health support, which provider stakeholders felt was an intangible benefit; they were offered the chance to address previous and new health concerns with youth. Engaging stakeholders at this STI clinic was beneficial for all: researchers gained information about at-risk youth who are often hard to reach, providers received more detailed and contextual information about their patients that directed care and referrals, and youth received tailored comprehensive healthcare.

Community health clinic

Recruitment at this site was a joint effort across stakeholders (e.g., patient stakeholders referred friends or family members, research stakeholders recruited patients and collaborated with clinic stakeholders). A critical aspect was one clinic stakeholder who was also a community member and the same ethnicity as most patient stakeholders (i.e., Arab descent). Having stakeholders who share the same cultural identity as community members is an advantage to the participatory research process (M. E. Miller & Vaughn, 2015; Savage et al., 2006). This individual’s strong community connections allowed her to readily recruit potential participants. Patient and clinic stakeholders on the project gained the benefit of enhanced patient-provider communication, which, for some outweighed their apprehension about participation. Research stakeholders discussed confidentiality with patient stakeholders and their role of working with clinic stakeholders to evaluate and improve communication quality and healthcare at the clinic. Research stakeholders reviewed the SREHC with patients to increase their comfort in using the tool as well. Obstacles to retention at this site included the transient nature of the population, work and school schedules, and disruptive patient behavior. For example, two patient stakeholders were involved in a physical altercation on clinic grounds. This resulted in an arrest and thus discontinuation as patients within this clinic and within this study.

Although the cultural adequacy of this interventional history tool with an Arab sample was not discussed prior to the study, major efforts went into making this a culturally responsive tool with feedback from individuals and groups of diverse ethnicities across pilot studies. Ultimately, the SREHC provided a more in-depth view into the experiences of Arab-American youth utilizing services at this site. A better understanding of youth within the Arab-American community was a shared goal among clinic and research stakeholders. Clinic stakeholders noted that the SREHC revealed patients’ engagement in risk behaviors that they were unaware of; namely, those in contrast to their community’s ethnic values and beliefs (e.g., premarital sex). The fact that clinic and patient stakeholders found this tool to be a positive addition to healthcare appointments supports the design of the SREHC. Namely, the SREHC has an open, person-centered format. As such, it does not need to be specific to one culture, since it is tailored to the patient. As depicted in Figure 1, the SREHC is a chart of open categories of potential life events, so the information is specific to the individual, their interpretation, and their experiences.

University health center

Clinic stakeholders at this site were eager to collaborate. They helped develop and carry out recruitment procedures with the research team’s Project Manager (e.g., posting flyers, contacting students, recruiting participants, and scheduling interviews). Due to the university context (e.g., living on campus) and relationships between the clinic and patient stakeholders, fewer recruitment and retention obstacles existed. Yet, limited space, large patient volume, and the academic calendar limited scheduling options for interviews and follow-ups. There were also several benefits for all stakeholders at this site. Although not directly assessed, clinic stakeholders noted an increase in patients due to study participation. That is, new patients stated wanting to seek services based on a friend’s positive experience in the study. Providers reported improved assessment and healthcare after using the SREHC, including more personalized healthcare recommendations and referrals to university counseling services.

Discussion

The take-home point of this study could be viewed as a challenge or benefit: it was necessary for all stakeholders to make constant adjustments to meet the needs of all stakeholders. That is, despite obstacles driving stakeholders to divert from original plans, stakeholders’ needs and desires were still honored. This study, by no means represents the perfect participatory research based project. However, it is an example of the lessons, benefits, and challenges faced when engaging in this work and ways to effectively troubleshoot very real situations that occur.

Our results indicate that the SREHC and person-centered, participatory research enhances cognitive appraisal and intentions for safer sex behavior. Youth-centered assessments like the SREHC offer an open dialogue about sensitive issues and facilitate discussion to reinforce safer sex practices. While some of the noted challenges were unique, others echo common challenges (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Koné et al., 2000). For example, ideally participatory research reflects equal contribution from all stakeholders, yet this is not the norm. Instead, researchers are encouraged to view participation as a continuum with fluctuating involvement from different partners throughout the project (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). A continuum approach is what we used in this study. When the original clinics withdrew from the study, three new sites joined the study. Although compromising some aspects of a pure participatory research approach (e.g., developing all of the research questions with input from all stakeholders), the majority of stakeholders and the original aim of the study remained unchanged. These adaptations are accepted and promoted by guiding agencies and funding groups (PCORI, 2013). Through several IRB amendments, we were able to update aspects of the study to meet the new clinic stakeholders’ interests and needs.

All stakeholders provided feedback throughout the course of the study via quantitative and qualitative data. When participatory research between stakeholders is formed, social justice is introduced and it is no longer decontextualized. The research occurs within sociocultural contexts and seeks to address unique needs of all stakeholders. These diverse environments can present challenges, which we encountered across sites; but we also gained insight from reflecting on these challenges in collaboration with stakeholders. For example, a unique challenge at the STI clinic was the model of care. This setting is particularly illustrative of the flexibility needed to conduct patient-centered participatory research. Despite limitations, this site provides services to high-risk youth most in need of services and research related to their sexual healthcare needs.

Sociocultural differences also impact the success of participatory research. For example, research stakeholders may seem as outsiders if they do not partner with stakeholders (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). This divide can vary if cultural issues are not considered; it is critical that research stakeholders are culturally sensitive, and include team members of each culture or community to recognize unique needs at the outset. In this study, the stakeholders from the Arab-American site were active early on. Although fewer obstacles were experienced at the university site, it is still necessary to understand the limitations of this environment. The structural barriers of working in a university setting determined when to conduct initial evaluations and follow-ups.

The relationships growing out of this participatory research experience encouraged mutuality with the common goal of providing quality healthcare aimed at long-term positive sexual health outcomes. The value of conducting this research lies in connecting with diverse stakeholders and working together to provide knowledge that impacts the lives of real people in the real world. As research is translated to practice, it is critical to integrate the expertise of clinic and patient stakeholders to ensure that interventions meet the needs of the communities they are intending to serve. This research could not succeed without the involvement of all stakeholders.

This study was informed by pilot studies and will likely inform future projects. Our work, and participatory research in general, is a cyclical learning process whereby stakeholders shape development at all phases. Our results coincide with those of MacQueen et al. (2001), in recognizing that this process differs across settings, especially the clinical setting where nursing researchers may work. There is no “cookbook approach” to participatory research-based projects (MacQueen et al., 2001, p. 1936). Researchers must work with stakeholders to understand how they view their participation and the ideal level of community involvement. Researchers using a participatory approach must realign their partnerships and goals with stakeholder needs (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). For example, using participants input, the SREHC was edited to elicit open and non-judgmental communication. These changes resonated well with patient stakeholders. As one patient noted, the SREHC “helped me because I actually went to my doctor and talked about some of the problems [mental health and sexual health] that I was having and I guess I felt more comfortable doing it because I actually wrote it down.” Clinic stakeholders also stated increased understanding of their patients (e.g., learning about the rates their patients were engaging in premarital sex) and ways to ensure quality healthcare (e.g., discuss safe sexual practices).

This approach should extend to settings with limited resources or those lacking coordinated systems of care. Although these settings may not be “easy” research sites, they are likely to serve vulnerable populations, such as at-risk youth seeking care in low-cost or free clinics, who are just as (if not more) important to include in participatory research. Overall, our findings offered support that patient-centered communication increased at all of sites. Providers reported that partnering in this study oriented them to patient/person-centered techniques that they were not utilizing effectively in their practice. Using the SREHC and engaging in patient-centered communication led to a better understanding of different questions to ask youth within to increase the effectiveness and relevance of health care, especially around sexual health and risk behaviors. As outsiders coming into a setting or community, researchers often carry a great deal of power and privilege that must be acknowledged to actualize the social justice component of community-engaged participatory research that seeks to include all stakeholders equally.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Access Community Health and Research Center, Washtenaw County Public Health Department, and Eastern Michigan University – University Health Services for their assistance with recruitment and data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Mental Health [grant number R34-MH-082644].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Nicole M. Fava, Florida International University in the Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work in Miami, FL..

Michelle L. Munro-Kramer, University of Michigan in the School of Nursing in Ann Arbor, Michigan..

Irene L. Felicetti, Perioperative Outcomes Initiative at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan..

Cynthia S. Darling-Fisher, University of Michigan in the School of Nursing in Ann Arbor, Michigan..

Michelle Pardee, University of Michigan in the School of Nursing in Ann Arbor, Michigan..

Abigail Helman, Case Western Reserve University in the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing in Cleveland, Ohio..

Elisa M. Trucco, Florida International University in the Psychology Department, Miami, FL..

Kristy K. Martyn, Clinical Advancement at Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing in Atlanta, Georgia..

References

- Ahrens KR, Richardson LP, Courtney ME, McCarty C, Simoni J, Katon W. Laboratory-diagnosed sexually transmitted infections in former foster youth compared with peers. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e97–e103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatricians Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. 2008 Retrieved from http://brightfutures.aap.org/pdfs/aap%20bright%20futures%20periodicity%20sched%20101107.pdf.

- Bay-Cheng LY. Beyond trickle-down benefits to research participants. Social Work Research. 2009;33(4):243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Belli RF, Lee EH, Stafford FP, Chow CH. Calendar and question-list survey methods: Association between interviewer behavior and data quality. Journal of Official Statistics. 2004;20:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:325–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulmus CN, Cristalli ME. A university-community partnership to advance research in practice settings: The HUB research model. Research on Social Work Practice. 2012;22(2):195–202. doi: 10.1177/1049731511423026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elster AB, Kuznets NJ. AMA guidelines for adolescent preventive services (GAPS): Recommendations and rationale. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: Necessary next steps. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2007;4(3):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. Retrieved from https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Knowing what works in health care: A roadmap for the nation. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2008. Retrieved from http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2008/Knowing-What-Works-in-Health-Care-A-Roadmap-for-the-Nation/KnowingWhatWorksreportbriefFINALforweb.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. Retrieved from https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2012/Best-Care/Best%20Care%20at%20Lower%20Cost_Recs.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, Tang G. Challenges and facilitators in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; Washington, DC: 2007. Retrieved from https://thenationalcampaign.org/resource/emerging-answers-2007%E2%80%94full-report. [Google Scholar]

- Koball H, Dion R, Gothro A, Bardos M, Dworsky A, Lansing J, Manning AE. Synthesis of research and resources to support at-risk youth. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2011. (OPRE Report # OPRE 2011-22) Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/synthesis_youth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Koné A, Sullivan M, Senturia K, Chrisman N, Ciske S, Krieger J. Improving collaboration between researchers and communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115(2/3):243–248. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, James S, Monn A, Kauten MC, Zhang J, Aarons G. Health-risk behaviors in young adolescents in the child welfare system. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:26–34. doi: 10.1016/jadohealth.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Stauss RP, Scotti R, Trotter RT., II What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1929–1938. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Darling-Fisher C, Smrtka J, Fernandez D, Martyn DH. Honoring family biculturalism: Avoidance of adolescent pregnancy among latinas in the United States. Hispanic Health Care International. 2006;4(1):15–26. doi: 10.1891/hhci.4.1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Martin R. Adolescent sexual risk assessment. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2003;8:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Reifsnider E, Murray A. Improving adolescent sexual risk assessment with event history calendars: A feasibility study. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Loveland-Cherry C, Villarruel AM, Gallegos Cabriales E, Zhou Y, Ronis D, Eakin B. Mexican adolescents’ alcohol use, family intimacy, and parent-adolescent communication. Journal of Family Nursing. 2009;15(2):152–170. doi: 10.1177/1074840709332865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Munro ML, Darling-Fisher CS, Ronis DL, Villarruel AM, Pardee M, Faleer H, Fava NM. Patient-centered communication and health assessment with youth. Nursing Research. 2013;62(6):383–393. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000005. PMID: 24165214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Kramer ML, Fava NM, Ronis DL, Darling-Fisher CS, Villarruel AM, Pardee M, Martyn KK. A provider-based intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors among youth. (in progress)

- McIntyre P, Williams G, Peattie S. Adolescent friendly health services: An agenda for change. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_FCH_CAH_02.14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centerd Outcomes Research Institute The PCORI methodology report. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/11/PCORI-Methodology-Report.pdf.

- Miller AL, Lopez L, Gonzalez JM, Dassori A, Bond G, Velligan D. Public-academic partnerships: Research in community mental health settings: A practicum experience for researchers. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1246–1248. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ME, Vaughn LM. Achieving a shared vision for girls’ health in a low-income community. Family & Community Health. 2015;38(1):98–107. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Passmore D, Baker E. A “triple threat” to research protocols and logistics: Adolescents, sexual health, and poverty. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2016;29(1):14–20. doi: 10.1177/0894318415614623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation M, Bess K, Voight A, Perkins DD, Juarez P. Levels of community engagement in youth violence prevention: The role of power in sustaining successful university-community partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(1-2):89–96. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Partnership for Civic Change University and community research partnerships: A new approach. 2003 Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/UCRP_report.pdf.

- Polit DE, Beck CT. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research: New and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(3):173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftner MA, Martyn KK, Momper SL, Kane Low L, Loveland-Cherry CS. Urban American Indian adolescent girls: Framing sexual risk behavior. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1043659614524789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage CL, Xu Y, Lee R, Rose BL, Kappesser M, Anthony JS. A case study in the use of community-based participatory research in public health nursing. Public Health Nursing. 2006;23(5):472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Wu JHC. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services . The guide to clinical preventive services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Washington, DC: 2012. (No. 12-05154) Retrieved from http://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/guide2012/guide-clinical-preventive-services.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence: Summary. Agency for Research on Health Quality; Rockville, MD: 2003. (No. 03-0037) Retrieved from http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/cbprrole.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]