Abstract

Objective

Isolated lateral compartment tibiofemoral radiographic osteoarthritis (IL-ROA) is an understudied form of knee osteoarthritis. The objective of the present study was to characterize MRI abnormalities and MR-T2 relaxation time measurements associated with IL-ROA and with isolated medial compartment ROA (IM-ROA) compared with knees without OA.

Method

200 case subjects with IL-ROA (Kellgren/Lawrence (K/L) grade≥2 and joint space narrowing (JSN)>0 in the lateral compartment but JSN=0 in the medial compartment) were randomly selected from the Osteoarthritis Initiative baseline visit. 200 cases with IM-ROA and 200 controls were frequency matched to the IL-ROA cases. Cases and controls were analyzed for odds of having a subregion with >10% cartilage area affected, with ≥25% bone marrow lesions (BML), with meniscal tear or maceration, and for association with cartilage T2 values.

Results

IL-ROA was more strongly associated with ipsilateral MRI knee pathologies than IM-ROA (IL-ROA: OR=135.2 for size of cartilage lesion, 95%CI 42.7–427.4; OR= 145.4 for large size bone marrow lesions (BML), 95%CI 41.5–509.5; OR =176 for meniscal tears, 95%CI 59.8–517.7; IM-ROA: OR=28.4 for size of cartilage lesion, 95%CI 14.7–54.7; OR= 38.1 for size of BML, 95%CI 12.7–114; OR =37.0 for meniscal tears, 95%CI 12–113.6). Cartilage T2 values were higher in both tibial and medial femoral compartments in IL-ROA, but in IM-ROA were only significantly different from controls in the medial femur.

Conclusion

IL-ROA knees show a greater prevalence and severity of MRI lesions and higher cartilage T2 values than IM-ROA knees compared with controls.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, lateral compartment, magnetic resonance imaging, cartilage

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, and afflicts at least 27 million US adults, almost 6 million more than in 1995 [1]. Knee OA is characterized by loss of articular cartilage, osteophytosis, and intermittent inflammation of the joint tissues, and is one of the most frequent causes of pain and disability in the elderly [2–5]. On radiograph, knee OA is characterized by a loss of joint space in the medial compartment and/or the lateral compartment of the joint. Isolated lateral compartment knee OA represents approximately 20.5% of all cases of radiographic knee OA, and has a higher prevalence in women compared with men and in African Americans compared with whites [6]. Isolated lateral compartment tibiofemoral radiographic osteoarthritis (IL-ROA) is common, but has not been studied sufficiently in comparison with isolated medial compartment radiographic osteoarthritis (IM-ROA).

Motion and geometry in the lateral compartment of the knee differs significantly from that in the medial compartment. Cooke et al found that in varus knee OA (a proxy for medial compartment OA) femoral geometry was abnormal (reduced condylar-hip angle) but tibial plateau-ankle geometry was similar to non-OA controls, while in valgus knee OA (a proxy for lateral compartment knee OA) the opposite held, with a finding of abnormal tibial geometry but normal femoral geometry [7]. Furthermore, Gulati et al found in surgical specimens that both tibial and femoral lesions were more posterior in lateral compartment knee OA than in medial, corresponding to sites of T-F contact during extension phase of gait for medial lesions but to flexion angles above those occurring in single leg stance of the gait cycle for lateral lesions [8]. The authors note that this suggests that “different mechanical factors are important in initiating the different types of OA” and that “activities other than gait are likely to induce lateral OA”.

Historically, knee OA has been evaluated by determining the presence of osteophytes and joint space narrowing (JSN) on radiograph which has been assumed to correlate with cartilage loss, but it has not been fully demonstrated that radiographically measured joint space width (JSW) accurately reflects cartilage thickness in the lateral compartment and can therefore be regarded as a reliable surrogate marker of early osteoarthritis cartilage loss. Buckland-Wright et al found in an arthrography-based study of knees with OA that JSW accurately estimated cartilage thickness in the medial but not in the lateral compartment [9]. In another study, knees obtained at joint replacement surgery for OA were compared with estimations of JSW by pre-surgical standing knee radiographs and significant differences between the radiologic measurement and surgical specimen measurement were observed in both medial and lateral arthrosis; however, lateral JSW measurements had a greater amount of variation of JSW by radiograph than did medial [10, 11]. There is also an acknowledged difference in the angle of the tibial plateau between medial and lateral compartments [12] which thus may make JSW estimates in the lateral compartment less accurate when read in radiographs optimized for assessment of the medial compartment. Although meniscal degeneration and position are associated with radiographic JSN in both medial and lateral compartments, it is unclear from prior studies whether the degree of this association differs between compartments [13]. The availability of 3 Tesla Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans of the knee and simultaneous radiographs of the knee in a large sample of subjects with, and at risk for, knee OA in the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) presented a novel opportunity to compare MRI lesion patterns between IL-ROA and medial compartment disease to better understand their pathophysiology.

In the past, assessment of cartilage composition was confined to ex-vivo analyses of arthroscopic or cadaveric specimens. With the advent of quantitative MRI techniques such as cartilage T2 mapping, a novel, non-invasive measure of cartilage health is available. This in-vivo technology enables the quantification of T2 relaxation times as functions of cartilage water and collagen content [14, 15]. Prior T2 studies have established a link between cartilage damage due to degeneration and elevated water content within the cartilage leading to increased cartilage T2 relaxation time measurements in degenerated knee cartilage [16, 17]. Other more recent work on T2 in the setting of knee osteoarthritis (OA) has demonstrated that T2 measurements can appropriately differentiate subjects with radiographic OA from normal controls [18, 19]. In this light, MRI-based T2 relaxation time measurements can be regarded as promising surrogate markers of cartilage integrity.

Previous studies of knee OA either have combined medial and lateral compartment ROA or have focused on medial compartment disease [20–23]. This has greatly limited our understanding of whether lateral compartment knee OA represents a pathology separate from or similar to medial compartment knee OA. The objective of the present study was to confirm suspected relationships between radiographic measures of JSN and MRI-based cartilage thickness measures in IL-ROA, to characterize IL-ROA in terms of other MRI lesions, and to investigate cartilage compositional properties (T2) in IL-ROA.

METHODS

Study Subjects

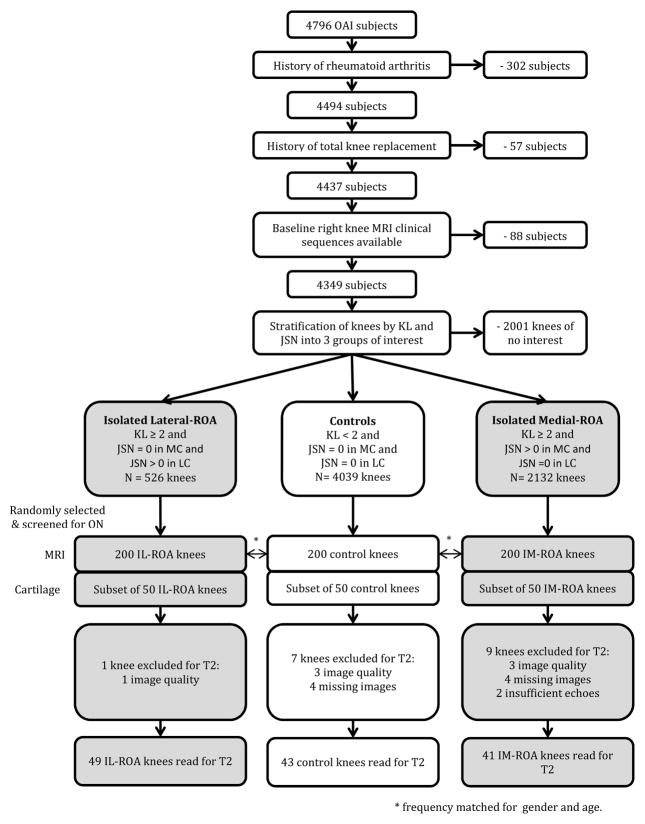

Six hundred subjects were selected from the OAI cohort, funded by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, which enrolled 4796 participants with or at high risk of knee OA at baseline (information available online at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu). Approval for the OAI project was given by the institutional review boards (IRB) at each OAI center, and for this project at the IRB at University of California, Davis. Three groups of knees were selected for this study, each comprised of 200 knees: one group with IL-ROA, one with IM-ROA, and one control group which had no knee OA in either compartment. Participants were excluded if they had rheumatoid arthritis, amputation or osteonecrosis, if they had had a knee replacement, or if they had no baseline MRI available. The 200 IL-ROA case knees were randomly selected from knees with the disease at baseline. 200 IM-ROA and 200 non-OA control knees were frequency matched to the IL-ROA case knees by sex and age in 10 year intervals (45–54 years/female, 45–54 years/male, 55–64 years/female, 55–64 years/male, 65–79 years/female, 65–79 years/male). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Study design flowchart for subject/knee inclusion.

Definition of Compartment-Specific Osteoarthritis

IL-ROA was defined radiographically as a knee with Kellgren-Lawrence (K/L) grade ≥2, JSN>0 in the lateral compartment and JSN=0 in the medial compartment using Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) grading. IM-ROA was defined as K/L≥2 with JSN>0 in the medial compartment and JSN=0 in the lateral compartment. Controls were defined as having K/L<2 and JSN=0 in in both lateral and medial compartments of the knee.

Knee Radiographs

Bilateral fixed-flexion posterior-anterior radiographs taken in SynaFlexer (Synarc, San Francisco, CA) plexiglass fixed-frame positioning were obtained at baseline and were read centrally and independently by two experienced readers with training in musculoskeletal imaging; disagreements were adjudicated. These radiographs were read for Kellgren/Lawrence grade (K/L grade, scale from 0 to 4 [24]) as a knee-level variable and joint space narrowing (JSN; OARSI grading; scale 0–4) by compartment.

MRI and Image Evaluation

Three Tesla knee images were obtained at four clinical sites using identical, calibrated MRI systems (Siemens, Erlanger, Germany) with standard knee coils [25]. All 600 MRIs of the knees were evaluated by one musculoskeletal radiologist (AG) with 15 years of experience who was blinded with regard to K/L status, case or control status, and all radiographic, demographic and clinical information. Cartilage and meniscal morphology was scored based on the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) scoring system [26]. For cartilage, the MOAKS scale is as follows: 0 = normal, 1.0 = 1–10% of the cartilage area damaged and no full-thickness cartilage loss, 1.1 = 1–10% of the area damaged and 1–10% full-thickness loss, 2.0 = 10–75% of the area damaged and no full-thickness loss, 2.1 = 10–75% of the area damaged and 1–10% full-thickness loss, 2.2 = 10–75% of the area damaged and 10–75% full-thickness loss, 3.0 = >75% of the area damaged and no full-thickness loss, 3.1 = >75% of the area damaged and 1–10% full-thickness loss, 3.2 = >75% of the area damaged and 10–75% full-thickness loss, 3.3 = >75% of the area damaged and >75% full-thickness loss. Meniscal abnormalities were scored using the following MOAKS classification: 0 = normal, 1 = intrasubstance signal abnormalities, 2 = vertical tear, 3 = horizontal and radial tear, 4 = complex tear, 5= root tear, 6 = partial maceration, 7 = progressive partial maceration, 8 = complete maceration [27]. Meniscal extrusion was graded as follows based on MOAKS: 0 = <2 mm; Grade 1 = 2–2.9 mm, Grade 2 = 3–4.9 mm; Grade 3 = >5 mm [27]. Bone marrow lesions (BML) were scored in the same subregions using MOAKS [27] categories, on a scale where 0 = no BML, 1 = BML involves <25% of the subregion, 2 = BML involves 25–50% of the subregion, and 3 = BML involves >50% of the subregion. Evidence of reliability for MRI semiquantitative scoring has been published previously [26, 27]. Both the tibial and femoral aspects of the tibiofemoral compartment were evaluated and scores in subregions (medial and lateral compartments each have anterior, central and posterior subregions for both tibia and femur) were assigned as above. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Representative 3 T Knee MRI images illustrating the most prominent knee pathologies observed in patients with isolated lateral compartment tibiofemoral radiographic osteoarthritis (IL-ROA). Image to the left (sag 3D DESS sequence): shows a severe cartilage lesion involving the lateral posterior femoral condyle. Middle image (sag Fat suppressed TSE sequence): depicts a severe lateral femoral bone marrow lesion. Image to the right (Sag Fat suppressed TSE): shows a lateral meniscal tear involving the anterior and posterior horn.

Cartilage T2 Relaxation Time Measurements

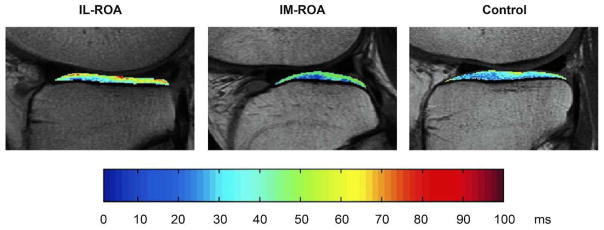

For the analysis of compartment-specific mean cartilage T2 values, we randomly selected a subset of 50 from the 200 subjects in the IL-ROA group, and then frequency matched 50 subjects each from the IM-ROA group and the control group. Articular knee cartilage was then manually segmented in four compartments (lateral and medial femur and lateral and medial tibia) and analyzed as described in detail previously [28, 29]. In general, we tried to segment as many slices as possible to encompass the maximum cartilage per compartment, but we also applied a strict image quality control as detailed before [30]. This typically resulted in 3–4 segmented slices for medial and lateral femur and 5–6 segmented slices for the medial and lateral tibia, but the number of slices could vary slightly depending on the overall knee size [30]. Mean T2 values in each compartment were calculated using a 3 parameter fitting function [31]. Of the 150 selected knees, 17 were not usable due to poor image quality or had no T2 maps due to missing echo files or insufficient echos (see Figure 1), leaving for the final analysis 49 knees with IL-ROA, 41 knees with IM-ROA and 43 control knees. All images were analyzed using a Sun Workstation (Sun Microsystems, Palo Alto, California, USA). Please see online supplementary document for detailed information about T2 segmentation, sequencing, fitting, and software used. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Representative cartilage T2 color maps of the lateral tibia shown for a subject with IL-ROA (on the left), a subject with IM-ROA (middle) and a control subject (on the right). Cartilage T2 color maps were overlaid on the first- echo images of the multislice multiecho (MSME) sequence. T2 values are displayed on a voxel by voxel basis. Blue voxels indicate low cartilage T2 values, red voxels signify high cartilage T2 values. Subjects with IL-ROA showed significantly higher mean T2 values than subjects with IM-ROA or controls (p<0.001).

Covariates

Data on age, race, and history of knee injury were collected at baseline in OAI by questionnaire. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using height and weight measured at baseline in OAI (http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/docs/StudyDesignProtocol.pdf).

Statistical Methods

We performed two case-control studies to assess the relation of MRI features to isolated OA in the medial and lateral compartments, separately. The corresponding compartment from the 200 non- ROA knees served as controls for each case group.

We compared the subjects’ characteristics between each of the two case groups and the control group, using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. In the study of IL-ROA, we derived the maximal scores for cartilage area, cartilage full thickness lesion, bone marrow lesion and meniscal tear and extrusion in the lateral compartment among cases and controls. The maximal score levels with less than 5 instances were collapsed for each MRI lesion (including BMLs). We performed a conditional logistic regression to assess the relation between each MRI feature in the lateral compartment and isolated lateral ROA, adjusting for age, race, history of knee injury, and BMI. We used the same method to evaluate the relation between MRI lesions in the medial compartment and IM-ROA. We then performed secondary analyses adjusting for the other MRI lesions present in the given compartment. For the T2 analysis, conditional logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association of IL-ROA and IM-ROA with T2 values separately compared with control knees, adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, and history of knee injury, all covariates which have been found to be associated previously with T2 values [30]. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS v9.2 (SAS, Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The mean age of 200 subjects with IL-ROA was 63.8 years, with mean BMI 29.5 kg/m2, 34.5% of whom were men, and 76.5% were white. The mean age of the 200 subjects with IM-ROA was 63.6 years, with mean BMI 29.8 kg/m2, 34.5% were men, and 76.0% were white. The mean age of the 200 non-cases was 63.1 years, 34.5% were men, with mean BMI 27.1 kg/m2, and 87.5% were white. The three groups were comparable in each of the matching categories, but the medial and lateral knee OA groups had higher percentages of non-Whites than did the non-case group (Table 1). For the centrally read radiographs, cross-sectional K/L grade scores had a kappa of 0.7. Medial JSN scores had a kappa of 0.75 and lateral JSN scores had a kappa of 0.75 (reliability scores available online at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu).

Table 1.

characteristics of participants

| No ROA (N=200) | IM-ROA (N=200) | IL-ROA (N=200) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD), year | 63.1 (8.5) | 63.6 (8.9) | 63.8 (8.8) |

| BMI, mean(SD), kg/m2 | 27.1 (4.2) | 29.8 (4.7) | 29.5 (5.2) |

| Female, N(%) | 131 (65.5) | 131 (65.5) | 131 (65.5) |

| White, N(%) | 174 (87.4) | 152 (76.0) | 153 (76.5) |

| College or above, N(%) | 139 (69.9) | 93 (46.5) | 125 (62.8) |

| History of knee injury, N(%) | 32 (16.2) | 66 (33.9) | 83 (41.7) |

| KL grade, N(%) | |||

| 0 | 156 (78.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 44 (22.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 106 (53.0) | 91 (45.5) |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 82 (41.0) | 79 (39.5) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 12 (6.0) | 30 (15.0) |

| WOMAC knee pain, mean(SD) | 1.6 (2.8) | 3.2 (3.4) | 3.9 (4.1) |

| Hip-knee-ankle angle, mean (SD), degree* | -0.4 (2.5) | -2.8 (3.6) | 3.1 (4.0) |

Hip-knee-ankle angle was measured on full-limb x-rays taken at follow-up visits

Lateral compartment MRI cartilage lesions were strongly associated with prevalent IL-ROA. Knees with IL-ROA had 135.2 times the odds of having a subregion of the lateral compartment with greater than 10% cartilage area affected as compared with knees without ROA (p<0.0001). Compared with knees with no ROA, IL-ROA knees also were: 41.5 times more likely to have a subregion of the lateral compartment with >10% full thickness cartilage lesions than no lesion (p<0.0001); 145.4 times more likely to have ≥25% of a region with BML than no lesion (p<0.0001); 176.0 times more likely to have a tear or maceration than no lesion (p<0.0001); and 45.3 times more likely to have a meniscal extrusion in any lateral compartment subregion than no extrusion (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence and severity of MRI lesions in the compartment with radiographic JSN for knees with IL-ROA and IM-ROA.

| MRI Lesion | Division Labels | Lesions in Medial Compartment in IM-ROA | Lesions in Lateral Compartment in IL-ROA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No ROA (n=200) | Medial ROA (n=200) | OR (95% CI)* | P | No ROA (n= 200) | Lateral ROA (n= 200) | OR (95% CI)* | P | ||

| Maximum Cartilage Area | 0:none | 128 | 25 | 1.0 | 111 | 4 | 1.0 | ||

| 1: 1–10%Area | 45 | 29 | 2.8 (1.4,5.7) | 0.0030 | 45 | 11 | 7.5 (2.1,27.3) | 0.0022 | |

| 2–3: >10%Area | 27 | 146 | 28.4 (14.7,54.7) | <.0001 | 44 | 185 | 135.2 (42.7,427.4) | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Cartilage with Full Thickness Lesion | 0:none | 193 | 129 | 1.0 | 186 | 87 | 1.0 | ||

| 1: 1–10%FT | 7 | 71 | 13.9 (6,32.1) | <.0001 | 9 | 15 | 4.8 (1.8,13) | 0.0018 | |

| 2–3: >10%FT | 5 | 98 | 41.5 (15.7,109.7) | <.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Size Bone Marrow Lesion | 0:none | 176 | 73 | 1.0 | 179 | 42 | 1.0 | ||

| 1: <25%region | 20 | 72 | 10 (5.3,18.6) | <.0001 | 18 | 61 | 13.7 (6.8,27.7) | <.0001 | |

| 2–3: >=25%region | 4 | 54 | 38.1 (12.7,114) | <.0001 | 3 | 97 | 145.4 (41.5,509.5) | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Meniscal Tear | 0:none | 43 | 28 | 1.0 | 119 | 6 | 1.0 | ||

| 1: Signal Abnormality | 113 | 42 | 0.7 (0.3,1.3) | 0.2539 | 54 | 12 | 4.3 (1.3,13.7) | 0.0144 | |

| 2–4: Tear | 39 | 45 | 3.4 (1.6,7.1) | 0.0015 | 27 | 182 | 176 (59.8,517.7) | <.0001 | |

| 6–8: Maceration | 5 | 85 | 37 (12,113.6) | <.0001 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Meniscal Extrusion | 0:none | 175 | 84 | 1.0 | 195 | 81 | 1.0 | ||

| 1–3: any region | 25 | 116 | 8.2 (4.8,14.1) | <.0001 | 5 | 118 | 45.3 (17.5,117.3) | <.0001 | |

Adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site and history of knee injury

Like IL-ROA, IM-ROA was strongly associated with medial compartment cartilage lesions, but the magnitude of the effect sizes were smaller than observed in IL-ROA. Knees with IM-ROA had 28.4 times the odds of having a subregion of the medial compartment with greater than 10% cartilage area affected as compared with knees without OA (p<0.0001). Compared with knees with no ROA, IM-ROA knees also were: 13.9 times more likely to have a subregion of the medial compartment with >10% full thickness cartilage lesions than no lesion (p<0.0001); 38.1 times more likely to have ≥25% of a region with BML than no lesion (p<0.0001); 37 times more likely to have a tear maceration than no lesion (p<0.0001); and 8.2 times more likely to have a meniscal extrusion in any medial compartment subregion than no extrusion (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

Trans-Compartment MRI Lesions

IL-ROA was also strongly associated with medial compartment cartilage lesions, but with smaller effect sizes. Knees with lateral compartment OA had 3.3 times the odds of having a subregion of the medial compartment with greater than 10% cartilage area affected as compared with knees without OA (p<0.0001). Compared with knees with no ROA, IL-ROA knees also were 5.4 times more likely to have ≥25% of a medial region with BML than no lesion (p=0.006); and 2.3 times more likely to have a meniscal extrusion in any medial compartment subregion than no extrusion (p=0.004). However, IL-ROA was not associated with full thickness lesions or meniscal tears in the medial compartment (Table 3). Unlike IL-ROA, IM-ROA was only marginally associated with lateral compartment subregion MRI lesions in a few scattered categories (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence and severity of MRI lesions in contralateral compartment from the site of the radiographic JSN for knees with IL-ROA and knees with IM-ROA.

| MRI lesion | Division Labels | Lesions in Medial Compartment in IL-ROA | Lesions in Lateral Compartment in IM-ROA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No ROA (n=200) | Lateral ROA (n=200) | OR (95% CI)* | P | No ROA (n=200) | Medial ROA (n=200) | OR (95% CI)* | P | ||

| Maximum Cartilage Area | 0:none | 128 | 78 | 1.0 | 111 | 101 | 1.0 | ||

| 1:1- 10%Area | 45 | 58 | 1.9 (1.1,3.3) | 0.0157 | 45 | 72 | 1.9 (1.1,3.2) | 0.0146 | |

| 2–3: >10%Area | 27 | 64 | 3.3 (1.9,6) | <.0001 | 44 | 27 | 0.6 (0.3,1) | 0.0639 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Cartilage with Full Thickness Lesion | 0:none | 193 | 184 | 1.0 | 186 | 184 | 1.0 | ||

| 1–3:>0%FT | 7 | 16 | 2.6(0.9,7) | 0.0641 | 14 | 16 | 0.9 (0.4,2.2) | 0.8701 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Size Bone Marrow Lesion | 0:none | 176 | 137 | 1.0 | 179 | 155 | 1.0 | ||

| 1:<25%region | 20 | 46 | 2.9 (1.5,5.4) | 0.0012 | 18 | 34 | 2(1,4) | 0.0380 | |

| 2–3: >=25%region | 4 | 17 | 5.4 (1.6,18) | 0.0056 | 3 | 10 | 3.2 (0.8,12.7) | 0.0900 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Meniscal Tear | 0:none | 43 | 40 | 1.0 | 119 | 132 | 1.0 | ||

| 1: Signal Abnormality | 113 | 100 | 0.9 (0.5,1.6) | 0.7566 | 54 | 43 | 0.6 (0.3,1) | 0.0436 | |

| 2–4: Tear | 39 | 39 | 1.2 (0.6,2.3) | 0.6775 | 27 | 25 | 0.9 (0.5,1.7) | 0.7218 | |

| 6–8: Maceration | 5 | 21 | 3 (1,9.5) | 0.0565 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Maximum Meniscal Extrusion | 0:none | 175 | 146 | 1.0 | 195 | 197 | 1.0 | ||

| 1–3: any region | 25 | 54 | 2.3 (1.3,4) | 0.0044 | 5 | 3 | 0.4 (0.1,1.9) | 0.2689 | |

Adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site and history of knee injury

Analyses Adjusted for Other MRI Lesions

We also performed analyses further adjusting for other MRI lesions within the same compartment. In a model that included cartilage full thickness lesions, BMLs, and meniscal tears, IL-ROA knees were still 3.6 times more likely to have a subregion with >10% full thickness lesion than no full thickness lesion (p=0.0537); were 13.9 times more likely to have a subregion with ≥25% BML than no lesion (p=0.0007); and were 48.6 times more likely to have a meniscal tear or maceration than no meniscal abnormality (P<0.0001) (Table 4). In a model including the same MRI lesions as above, IM-ROA knees were 3.7 times more likely to have a subregion with any full thickness lesion than no full thickness lesion (p=0.0203); 9.5 times more likely to have a subregion with ≥25% BML than no BML; and 15.2 times more likely to have meniscal maceration than no meniscal abnormality (p<0.0001) (Table 5).

Table 4.

IL-ROA and cartilage thickness, bone marrow lesion and meniscal tear measured in the lateral compartment, adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, and history of knee injury and each of the other MRI features.

| Divisions | Adjusted Model – IL-ROA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| OR (95% CI)* | P | ||

| Maximal lateral Cartilage Full Thickness lesion | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1:1–10%FT | 1.1(0.3,4.2) | 0.8487 | |

| 2–3:>10%FT | 3.6(1,13.6) | 0.0537 | |

|

| |||

| Maximal Lateral Bone Marrow Lesion | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1:<25%region | 3.4(1.4,8.5) | 0.0090 | |

| 2–3:>=25%region | 13.9(3,63.2) | 0.0007 | |

|

| |||

| Maximal Lateral Meniscal Tear | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1:SignalAbnormality | 3.1(0.9,10.3) | 0.0713 | |

| 2–8:TearMaceration | 48.6(15.8,149.5) | <.0001 | |

Adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, history of knee injury and each of the other MRI features.

Table 5.

IM-ROA and cartilage thickness, bone marrow lesion, and meniscal tear measured in the medial compartment, adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, history of knee injury and each of the other MRI features.

| Divisions | Adjusted Model – IM-ROA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| OR (95% CI)* | P | ||

| Maximal Medial Cartilage Full Thickness Lesion | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1–3:anyFT | 3.7(1.2,10.9) | 0.0203 | |

|

| |||

| Maximal Medial Bone Marrow Lesion | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1:<25%region | 5.2(2.5,10.5) | <.0001 | |

| 2–3:>=25%region | 9.5(2.6,34.3) | 0.0006 | |

|

| |||

| Maximal Medial Meniscal Tear | 0:none | 1.0 | |

| 1:SignalAbnormality | 0.7(0.3,1.5) | 0.3621 | |

| 2–4:Tear | 2.6(1.1,6.1) | 0.0231 | |

| 6–8:Maceration | 15.2(4.6,50.7) | <.0001 | |

Adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, history of knee injury and each of the other MRI features.

Results of Compartment-Specific T2 Relaxation Time Measurements

For the T2 analyses, significant associations were observed between IL-ROA and T2 values in the lateral (p=0.0001) and medial tibia (p=0.0129), as well as with the medial femur (p=0.0022); no significant association was found for IL-ROA and T2 values in the lateral femur. There was a significant association between IM-ROA and T2 values for the medial femur (p=0.0357) but no significant association was found for IM-ROA and T2 values in any of the other compartments (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Unadjusted mean cartilage MRI T2 relaxation time values ± SD (in ms) by compartment and by group. IL-ROA = radiographic Osteoarthritis isolated to the lateral tibiofemoral compartment. IM-ROA = radiographic Osteoarthritis isolated to the medial tibiofemoral compartment. Controls are subjects without radiographic evidence of Osteoarthritis.

| T2 measurements by compartment (ms) | IL-ROA group (n=49)* | IM-ROA (n=40) | Controls (n=42) | p value † IL-ROA vs IM-ROA | p value † IL-ROA vs controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral femur (LF) | 35.59 ± 2.94 | 35.51 ± 2.54 | 34.90 ± 2.44 | 0.990 | 0.554 |

| Lateral tibia (LT) | 31.03 ± 2.82 | 28.45 ± 2.03 | 28.72 ± 2.46 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Medial femur (MF) | 39.15 ± 2.46 | 38.71 ± 2.91 | 37.97 ± 2.64 | 0.720 | 0.091 |

| Medial tibia (MT) | 30.57 ± 2.12 | 30.11 ± 2.28 | 29.40 ± 2.41 | 0.600 | 0.040 |

Only 48 out of 49 IL-ROA knees had T2 measurements at the lateral tibia.

p-values were calculated using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey testing. Statistical significance was assumed at p< 0.05.

Table 7.

Results of T2 conditional logistic regression analysis, separately showing odds of compartment specific knee ROA per 1 unit (ms) increase in T2 measurement, adjusting for age, BMI, race, clinic site, and history of knee injury in each compartment evaluated.

| IL-ROA compared with no ROA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Model | ||

| Compartment | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Lateral Femur | 1.14 (0.96, 1.36) | 0.1464 |

| Lateral Tibia | 1.47 (1.20, 1.79) | 0.0001 |

| Medial Femur | 1.40 (1.13, 1.74) | 0.0022 |

| Medial Tibia | 1.30 (1.06, 1.59) | 0.0129 |

| IM-ROA compared with no ROA | ||

| Adjusted Model | ||

| Compartment | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Lateral Femur | 1.15 (0.92, 1.44) | 0.2100 |

| Lateral Tibia | 0.93 (0.73, 1.18) | 0.5336 |

| Medial Femur | 1.23 (1.01, 1.49) | 0.0357 |

| Medial Tibia | 1.11 (0.89, 1.39) | 0.3505 |

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that IL-ROA is associated with greater severity of all types of MRI lesions than IM-ROA is, and gives the first comprehensive picture of lateral compartment disease in terms of MRI-detected pathologies, including cartilage biochemical status (T2). Furthermore, IL-ROA appears to be associated with significant medial compartment MRI lesions as well, while IM-ROA does not demonstrate a comparable association with lateral compartment MRI lesions. While these findings confirm an expected relationship between IL-ROA and the presence of MRI lesions, we also for the first time explicitly characterized the patterns of MRI lesions in lateral disease and compared them with IM-ROA.

Knee ROA in the lateral compartment is less prevalent than medial compartment disease. Our research group recently reported that in the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) knees with ROA at baseline (defined as K/L grade >=2), 20.5% had isolated lateral compartment tibiofemoral ROA (compartment-specific JSN) > 0), 5.7% had mixed lateral and medial, and 73.7% had isolated medial disease [6]. A number of studies have explored the relation between radiographic JSN and cartilage loss on MRI, but have done so specifically in the medial compartment of the knee. Beattie et al found that in the medial compartment in individuals without knee ROA, a substantial amount of the variation in minimum JSW can be explained by variation in cartilage thickness of the medial tibia [32]. Knees with medial JSN were found cross-sectionally to have smaller medial and lateral cartilage volume, although the association may have been confounded in part by sex [33]. Eckstein et al. found that radiographic JSN grades were associated with estimates of differences in cartilage thickness by MRI [21] but this study was limited to knees with medial compartment disease. We found no prior studies that specifically characterized the relation between IL-ROA and MRI lesions in all compartments as we have here.

The present study demonstrates not only a greater severity of MRI lesions associated with IL-ROA in the lateral compartment, but that IL-ROA also is associated with MRI lesions in the related medial compartment, while medial compartment disease largely does not demonstrate a comparable association with lesions in the lateral compartment, pointing again to the apparently more intensive nature of IL-ROA, involving more of the knee joint. Both of the case groups represent the distribution of participants by age and by sex in the OAI as a whole, so these differences are not an artifact of inappropriate selection. These interesting findings suggest that lateral compartment disease is a more destructive process in cartilage and meniscus that involves more of the knee than does medial disease, or that it is a faster moving process, and that we are observing a later stage in the knee OA disease.

The present study also demonstrates a larger effect size between IL-ROA and meniscal lesions than exists for IM-ROA. Englund et al. reported that meniscal tear is associated with incident radiographic knee OA (although they did not separate out lateral compartment lesions) [22] and Chang et al. reported that meniscal tears appear to exert detrimental effects on cartilage surfaces at a local level [34]. The higher prevalence of meniscal findings in the lateral compartment in the present study may be a factor in the cartilage loss observed in the lateral compartment as well.

We observed differences in the cartilage T2 values between lateral and medial compartment disease which support the MRI findings from a biochemical perspective. Specifically, the MOAKS scoring indicating greater severity of MRI lesions in IL-ROA with the largest odds ratios in the lateral compartment itself are mirrored in the finding that the greatest magnitude of association for the cartilage T2 was in the lateral tibia in IL-ROA. It is also worth noting that IL-ROA is associated with significantly higher cartilage T2 values even in the medial compartment where the radiographs had demonstrated a JSN score of 0, once again consistent with the MOAKS findings of significant medial compartment involvement in IL-ROA. Prior studies have demonstrated that knees with OA have higher cartilage T2 values than non-diseased knees [20] and that higher T2 values are associated with progression of cartilage degeneration [23], but in each of these studies lateral and medial compartment disease were not analyzed separately and lateral disease would have been under-represented given the numbers of knees analyzed.

This study has a number of strengths. First, the OAI is a large community based cohort with reliable and detailed covariate information. The radiographs were obtained using a careful and well-considered protocol, and readings were done in a centralized, standardized manner. The MRI collection process was also standardized. The MOAKS scores in this project were read by a single expert reader with extensive experience specifically using the OAI MRIs. The OAI itself encompasses a large participant group of men, women and whites and African Americans. We matched the knees in this study by age and sex to reflect the overall OAI cohort, so that the results are generalizable to persons in the US with knee OA or at high risk of it.

The study also has some limitations. Although knee radiographs were carefully and consistently obtained and centrally read per protocol, JSN and other radiographic features sometimes may not be fully evaluable which can result in misclassification bias. There are also elements of judgment that enter into the MRI reading and T2 segmentation process that may result in under-reporting or over-reporting of findings; however, these MRIs were evaluated by experienced readers and reproducibility figures are quite good as noted in the methods section.

In summary, subjects with isolated lateral compartment radiographic knee OA have more severe cis-compartment and trans-compartment MRI lesions, including meniscal damage, than do subjects with isolated medial compartment radiographic knee OA, and that IL-ROA is associated with higher cartilage T2 values. These differences in imaging presentation and T2 relaxation time measurement of lateral compartment disease are distinct from medial compartment disease and the greater severity of the lateral compartment MRI findings at presentation suggest that researchers in knee OA should separately consider these two subgroups as distinct phenotypes of knee OA in future epidemiologic and intervention studies. Furthermore, additional studies are now warranted to determine if subjects that present with pain and radiographic evidence of lateral compartment knee OA progress more rapidly than medial compartment knee OA and require earlier medical or surgical intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the following funding sources: the Center for Musculoskeletal Health at University of California, Davis School of Medicine; NIH K24 AR048841 (NEL); NIH P50 AR060752 (BLW, NEL); NIH P50 AR063043 (BLW, NEL); the University of California, Davis Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Program (NIH K12HD051958) (BLW); the Endowed Chair for Aging at University of California, Davis School of Medicine (NEL); NIH AR47785 (JN, DTF); Pivotal Osteoarthritis Initiative MRI Analyses (POMA: NIH/NHLBI contract no. HHSN2682010000 21C). The Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) is a public–private partnership comprised of 5 contracts (N01-AR-2-2258, N01-AR-2-2259, N01-AR-2-2260, N01-AR-2-2261, and N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the NIH, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Pfizer, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Merck Research Laboratories, and Glaxo-SmithKline. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the NIH.

The authors thank the participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative. We would also like to thank the Pivotal Osteoarthritis Initiative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis (POMA) and National Institutes of Health grant # AR47785 for contributing some MRI reads for the analysis.

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

The study sponsors (National Institutes of Health) had no involvement in the analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

BLW has had a contract with Pfizer, Inc., for unrelated work in the last 5 years. AG is the President of the Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to TissueGene, Genzyme, OrthoTrophix and Merck Serono. Other authors had no competing interests.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

BLW has had a contract with Pfizer, Inc., for unrelated work in the last 5 years. AG is the President of the Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to TissueGene, Genzyme, OrthoTrophix and Merck Serono. Other authors had no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and Design: BLW, YZ, NEL

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: BLW, JL, FL, UH, EK, JN, YZ, NEL

Drafting of the Article: BLW, NEL, UH

Critical Revision of the Article for Important Intellectual Content: BLW, JL, FL, UH, JN, DTF, YZ, KK, AG, NEL

Final Approval of the Article: BLW, JN, JL, FL, AG, YZ, DTF, KK, UH, EK, NE

Collection and Assembly of Data: AG, BLW, JL, FL, DTF, KK, UH, E

Obtaining Funding: BLW, NEL

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Barton L. Wise, Center for Musculoskeletal Health, University of California, Davis School of Medicine, 4625 2nd Avenue, Suite 2002, Sacramento, CA 95817.

Jingbo Niu, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Ali Guermazi, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Felix Liu, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Ursula Heilmeier, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Eric Ku, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

John A. Lynch, University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Yuqing Zhang, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

David T. Felson, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

C. Kent Kwoh, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tuscon, AZ.

Nancy E. Lane, University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Knee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: evidence from the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ettinger WH, Jr, Fried LP, Harris T, Shemanski L, Schulz R, Robbins J. Self-reported causes of physical disability in older people: the Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1035–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, Kazis L, Castelli W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:914–918. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbrugge LM, Lepkowski JM, Konkol LL. Levels of disability among U.S. adults with arthritis. J Gerontol. 1991;46:S71–83. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.2.s71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise BL, Niu J, Yang M, Lane NE, Harvey W, Felson DT, et al. Patterns of compartment involvement in tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in men and women and in whites and African Americans. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:847–852. doi: 10.1002/acr.21606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke D, Scudamore A, Li J, Wyss U, Bryant T, Costigan P. Axial lower-limb alignment: comparison of knee geometry in normal volunteers and osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulati A, Chau R, Beard DJ, Price AJ, Gill HS, Murray DW. Localization of the full-thickness cartilage lesions in medial and lateral unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1339–1346. doi: 10.1002/jor.20880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckland-Wright JC, Macfarlane DG, Lynch JA, Jasani MK, Bradshaw CR. Joint space width measures cartilage thickness in osteoarthritis of the knee: high resolution plain film and double contrast macroradiographic investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:263–268. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidow J. Lateral osteoarthritis of the knee. Etiology based on morphological, anatomical, kinematic and kinetic observations. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2006;77:3–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weidow J, Mars I, Cederlund CG, Karrholm J. Standing radiographs underestimate joint width: comparison before and after resection of the joint in 34 total knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:315–322. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashemi J, Chandrashekar N, Gill B, Beynnon BD, Slauterbeck JR, Schutt RC, Jr, et al. The geometry of the tibial plateau and its influence on the biomechanics of the tibiofemoral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:2724–2734. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Tu X, Lavalley M, Niu JB, Amin S, et al. Change in joint space width: hyaline articular cartilage loss or alteration in meniscus? Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2488–2495. doi: 10.1002/art.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lusse S, Claassen H, Gehrke T, Hassenpflug J, Schunke M, Heller M, et al. Evaluation of water content by spatially resolved transverse relaxation times of human articular cartilage. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;18:423–430. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ. Cartilage MRI T2 relaxation time mapping: overview and applications. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2004;8:355–368. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong CG, Mow VC. Variations in the intrinsic mechanical properties of human articular cartilage with age, degeneration, and water content. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ, Smith MB. Human articular cartilage: influence of aging and early symptomatic degeneration on the spatial variation of T2--preliminary findings at 3 T. Radiology. 2000;214:259–266. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja15259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumenkrantz G, Stahl R, Carballido-Gamio J, Zhao S, Lu Y, Munoz T, et al. The feasibility of characterizing the spatial distribution of cartilage T(2) using texture analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carballido-Gamio J, Stahl R, Blumenkrantz G, Romero A, Majumdar S, Link TM. Spatial analysis of magnetic resonance T1rho and T2 relaxation times improves classification between subjects with and without osteoarthritis. Med Phys. 2009;36:4059–4067. doi: 10.1118/1.3187228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn TC, Lu Y, Jin H, Ries MD, Majumdar S. T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology. 2004;232:592–598. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckstein F, Wirth W, Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Kwoh CK, Nelson DR, et al. Magnitude and regional distribution of cartilage loss associated with grades of joint space narrowing in radiographic osteoarthritis--data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englund M, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Aliabadi P, Yang M, Lewis CE, et al. Meniscal tear in knees without surgery and the development of radiographic osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly persons: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:831–839. doi: 10.1002/art.24383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph GB, Baum T, Alizai H, Carballido-Gamio J, Nardo L, Virayavanich W, et al. Baseline mean and heterogeneity of MR cartilage T2 are associated with morphologic degeneration of cartilage, meniscus, and bone marrow over 3 years--data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Lo GH, Grainger AJ, Conaghan PG, Boudreau RM, et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: MOAKS (MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:990–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, Tirman PF, Miaux Y, White D, et al. Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kretzschmar M, Lin W, Nardo L, Joseph GB, Dunlop DD, Heilmeier U, et al. Association of physical activity measured by accelerometer, knee joint abnormalities and cartilage T2-measurements obtained from 3T MRI: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015 doi: 10.1002/acr.22586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu A, Heilmeier U, Kretzschmar M, Joseph GB, Liu F, Liebl H, et al. Racial differences in biochemical knee cartilage composition between African-American and Caucasian-American women with 3 T MR-based T2 relaxation time measurements--data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:1595–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph GB, McCulloch CE, Nevitt MC, Heilmeier U, Nardo L, Lynch JA, et al. A reference database of cartilage 3 T MRI T2 values in knees without diagnostic evidence of cartilage degeneration: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebl H, Joseph G, Nevitt MC, Singh N, Heilmeier U, Subburaj K, et al. Early T2 changes predict onset of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1353–1359. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beattie KA, Duryea J, Pui M, O’Neill J, Boulos P, Webber CE, et al. Minimum joint space width and tibial cartilage morphology in the knees of healthy individuals: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones G, Ding C, Scott F, Glisson M, Cicuttini F. Early radiographic osteoarthritis is associated with substantial changes in cartilage volume and tibial bone surface area in both males and females. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang A, Moisio K, Chmiel JS, Eckstein F, Guermazi A, Almagor O, et al. Subregional effects of meniscal tears on cartilage loss over 2 years in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:74–79. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.130278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.