Abstract

Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the molecule that conveys genetic information from DNA to the translation apparatus. mRNAs in all organisms display a wide range of stability, and mechanisms have evolved to selectively and differentially regulate individual mRNA stability in response to intra-cellular and extra-cellular cues. In recent years, three seemingly distinct aspects of RNA biology—mRNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, alternative 3’ end processing and polyadenylation (APA), and mRNA codon usage—have been linked to mRNA turnover, and all three aspects function to regulate global mRNA stability in cis. Here, we discuss the discovery and molecular dissection of these mechanisms in relation to how they impact the intrinsic decay rate of mRNA in eukaryotes, leading to transcriptome reprogramming.

Keywords: mRNA turnover, m6A, codon optimality, alternative polyadenylation, transcriptome reprogramming

Study of mRNA turnover moving into the genomic era

Degradation of mRNAs plays an essential role in modulation of gene expression and quality control of mRNA biogenesis. RNA destabilizing elements, such as the AU-rich elements (AREs), are commonly found in the 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) of vertebrate mRNAs, particularly in those unstable messages coding for proto-oncogene products, cytokines, and transcription factors [1]. Typically, studies of mRNA turnover have used model constructs where transcription of the mRNA of interest is driven from a strong heterologous promoter [2, 3]. To pinpoint the regulatory RNA elements, DNA sequences coding for the mRNA of interest, such as a cloned cDNA, a piece of intron-containing genomic DNA or a hybrid gene, and genetic engineering are applied to systematically dissect the transcript [4]. Combining this approach with the power of genetics has provided a clear picture of eukaryotic mRNA decay pathways and participating decay factors, along with detailed mechanistic steps [5].

It is clear now that the decay rates of individual mRNAs can be highly variable and can be adjusted to meet cellular needs. When combined with regulation at the level of transcription and translation, this allows for great precision and flexibility in controlling specific gene expression. However, in the new era of –omics, what has been lagging behind prominent advances in the field of RNA turnover is an understanding of the role of mRNA turnover in shaping or reprogramming the global mRNA expression profile of eukaryotic cells when cells respond to intra- or extra-cellular stimuli. Equally important is a related issue concerning how intrinsic rates of decay for mRNA across the transcriptome may be established and what the underlying mechanism(s) and regulation are.

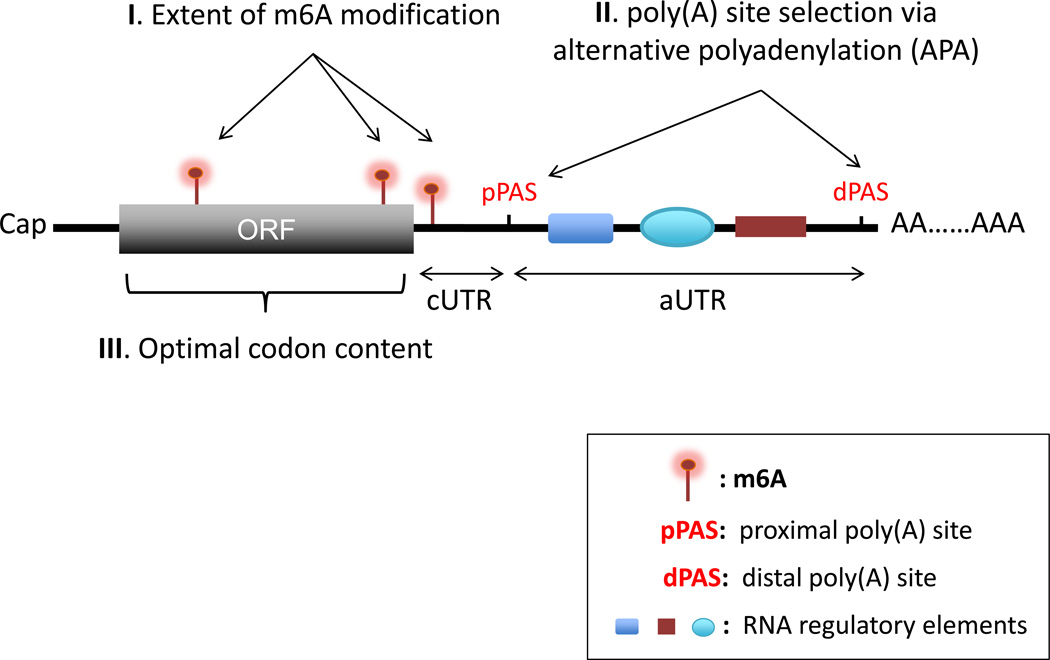

Three seemingly distinct aspects of RNA biology—N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification [6], alternative 3’ end processing and polyadenylation (APA) [7, 8], and codon optimality [9]—have been found to connect to mRNA turnover. They all function in cis and contribute to shaping or reshaping the intrinsic decay rates of mRNA across the transcriptome. In this review, we discuss the discovery and dissection of these mechanisms of global regulation of mRNA turnover in eukaryotes. To a first approximation, the effects of these mechanisms may be considered “cis-acting”, as they reside in or near the gene or mRNA being regulated. We also highlight some questions that are driving research in these three areas and the implications that their answers have for our understanding of how changes in global mRNA turnover can help to reprogram the transcriptome.

Epitranscriptomics of m6A

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), discovered over 4 decades ago, is the most abundant modification in eukaryotic mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) [10]. The discovery of fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) as a RNA demethylase [11] and subsequent technological developments to map m6A sites across the transcriptome [12–14] have given rise to the rapidly developing field of “m6A epitranscriptomics” [6]. Recent studies also suggest the importance of this new epigenetic mark in physiological and pathological processes [6, 15, 16]. While the mechanisms by which m6A regulates cellular mRNA functions are still being uncovered, the studies to date have provided important insight into how m6A modification contributes to the processing, localization, translation, and turnover of mRNAs in eukaryotic cells [15, 17]. Here, we focus on the impact of m6A on mRNA stability.

A few years ago, tens of thousands of m6A sites in mammalian mRNA were identified through methods combining m6A-RNA immunoprecipitation and deep-sequencing [12, 13]. These methods, termed m6A-seq or MeRIP-seq, have helped to identify m6A RNA-seq peaks in ~25% of all transcripts in human cells. Although m6A also occurs sporadically in coding regions and 5′ UTRs, it is typically enriched in long exons, near stop codons, and in 3′ UTRs. The 3’ UTR of mRNA is a hotspot for cis-regulatory elements, such as microRNA (miRNA) binding sites and AU-rich elements (AREs), that control mRNA localization, stability, and translation. Thus, the concentration of m6A in 3' UTRs of many mRNAs hints that m6A modification may influence the post-transcriptional fates of those mRNAs.

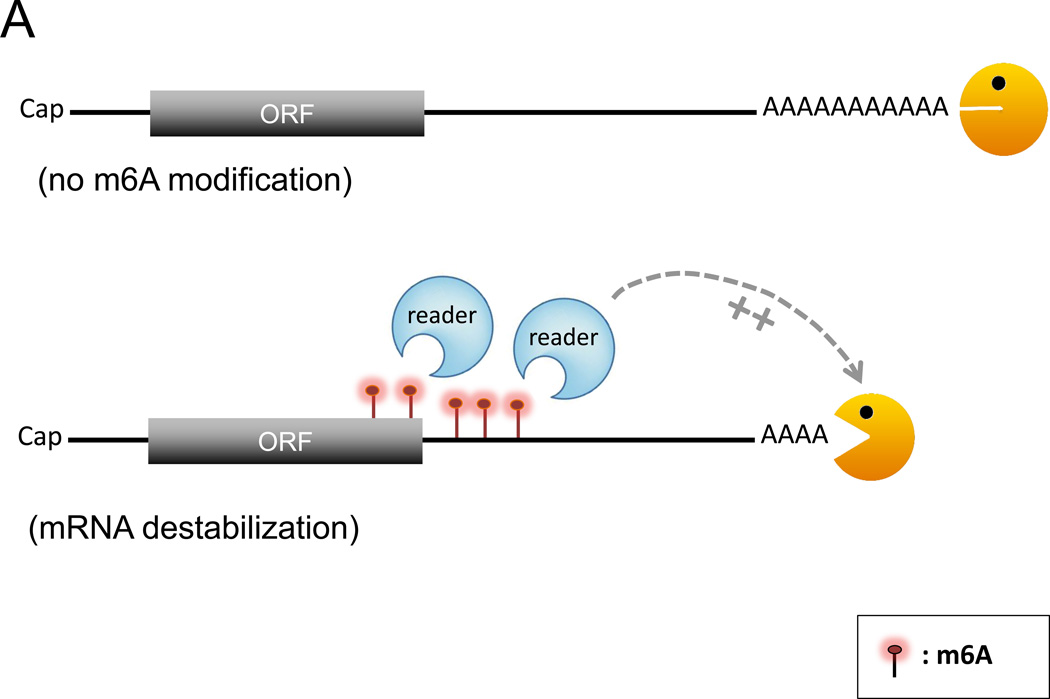

The mammalian m6A modification system has at least three key components (Box 1): the writers (i.e., the methyltransferases), the erasers (i.e., the demethylases), and the readers (i.e., effector proteins that directly bind m6A) [15, 17, 18]. Studies of the m6A readers reveal an interesting link between m6A modification and mRNA turnover rate. For example, a recent study [19] using m6A-RNA as bait to pull down binding proteins from human cell lysates identified YTH-domain family (YTHDF) proteins as possible binders of m6A-RNA and found that YTHDF2 enhanced degradation of many cellular transcripts. It appears that YTHDF2 binds to many m6A-containing mRNAs that are not being actively translated and co-localizes with cytoplasmic processing bodies (P bodies), which are cytoplasmic domains enriched in decay factors and translation repressors [20]. Subsequent experiments [20] showed that tethering of YTHDF2 to the 3' UTR of a normally stable mRNA triggered rapid decay of the mRNA. These observations are consistent with the notion that YTHDF2 either directly promotes mRNA decay (Fig. 1A) or recruits targeted mRNAs to P bodies in the cytoplasm for degradation or translation silencing. In contrast, another reader protein, YTHDF1, selectively binds m6A-modified mRNAs and promotes their translation by interacting with the translation machinery, presumably promoting ribosome loading of m6A-modified mRNAs [21]. This effect is readily observed during cellular stress responses [21]. It was suggested that when a cell is under stress, YTHDF1 is driven into stress granules, stabilizing stalled translation-initiation complexes within the stress granules. Once the stress is relieved, the YTHDF1-bound, stalled mRNAs can rapidly resume translation. Thus, m6A-modified mRNAs may hold an advantage over non-methylated transcripts during the stress response. It is worth noting that YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 share a large set of common mRNA targets that are usually unstable [19, 21], suggesting that the countervailing actions of YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 on mRNA fate are coordinated to balance the expression levels of transcripts that have short lifetimes.

Box 1. The m6A modification system.

The dynamics of reversible m6A modification in mRNAs are controlled by a system with at least three components: i) the “writers”, including the METTL3 and METTL14 methyltransferases, and at least one co-factor, WTAP; ii) the “erasers”, including the FTO and ALKBH5 demethylases; and iii) the “readers", effectors which include at least five proteins (YTHDF1–3 and YTHDC1–2) that are believed to directly interact with m6A [15, 17, 18]. The balance between activities of the writers and the erasers determines a transcriptome's extent of m6A modification, which, together with the m6A readers, influences the function and fate of m6A-modified mRNAs. Disruption of m6A modification system components can change the global m6A levels in cellular mRNA and has been linked to a variety of phenotypes [18]. How m6A modification achieves such wide-ranging pathophysiological effects is only beginning to be understood and is the subject of a recent burst of review articles.

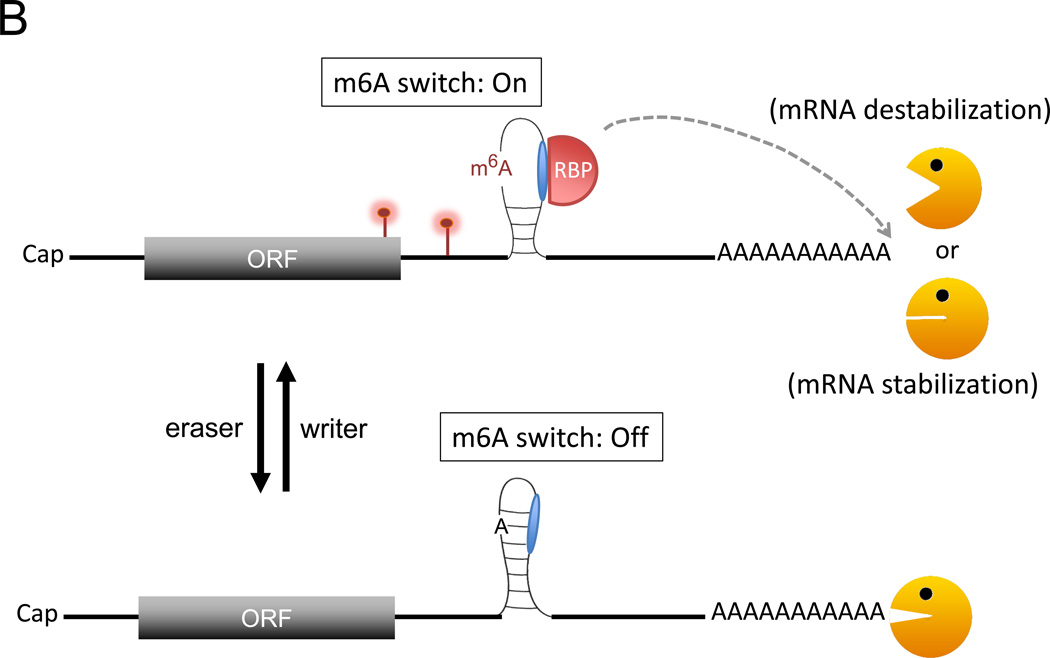

Figure 1.

Models of how m6A modification might affect the stability of a transcript. A. When a transcript gets m6A modification (red lollypops), binding of reader proteins to m6A modified site(s), particularly near the translation termination codon, may promote deadenylation of the targeted mRNA and enhance its degradation. B. An example illustrating how an m6A switch could control local RNA secondary structure. The m6A modification of a base-paired adenylate leads to exposure of a single-stranded RNA motif, facilitating its binding by a cognate RNA-binding protein (RBP). Depending on the nature of the RBP, the mRNA can be either destabilized or stabilized. C. HuR binding to a U-rich region in the 3’UTR results in stabilization of the targeted mRNA. When this binding is impaired by adjacent m6A residues, the mRNA is no longer stabilized by HuR. Not depicted are m6A modifications at other regions of mRNA and their effects on translation dynamics. Orange Pac man: deadenylase complex.

As with many other RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), the m6A-reader proteins identified to date contain intrinsically disordered regions (IDR) characterized by an enrichment of non-charged, polar amino acids [22, 23]. One prominent feature of mammalian IDR-containing RBPs is that they promote formation of RNA granules [24, 25], such as stress granules or P bodies [26]. Recent studies show that membrane-free RNA granules consist mainly of IDR-containing RBPs, and that the IDR domains are required for formation of these granules [24, 27]. Further, the YTHDF2 protein has been found to contain a Pro/Gln/Asn (P/Q/N)-rich domain essential for recruiting the YTHDF2–RNA complex to P bodies [19]. Since m6A readers are IDR-containing RBPs which may direct the associated mRNAs to specific cellular sites or granules, identification of proteins and RNA molecule constituents in m6A-reader containing granules under various cellular conditions would greatly help identify biological pathways regulated by m6A modification.

Another mechanism by which m6A regulates mRNA stability globally is by effects on RNA structure. The emerging concept of m6A as a switch to alter RNA structure comes from transcriptome-wide RNA structural mapping analyses in vitro and in vivo [28, 29]. The results have revealed that RNA structures adjacent to m6A sites tend to be more single-stranded than nonmethylated RNA regions. It appears that reversible m6A modification may function as a switch to “turn on or off” particular RNA-structure motifs within mRNAs and lncRNAs. This modulation of RNA structure driven by m6A may add another layer of control affecting RNA-protein, RNA-RNA and even RNA-DNA interactions across the transcriptome (Fig. 1B). For instance, the U-tract motifs located in the stems of RNA stem-loop structures often base-pair with the m6A consensus motif, RRACH (R=A or G, H=A, C, or U) [30]. Methylation of the adenosine residue within the RRACH motif (A => m6A) leads to destabilization of the stem structure, causing the U-tract motif to be exposed as single-stranded and more readily accessible for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (hnRNPC) binding. Another study [31] found that nearby m6A residues impaired the interaction of HuR (a RBP that stabilizes ARE-containing mRNAs) with its typical U-rich binding site of target mRNAs (Fig. 1C). These observations suggest that m6A can influence interaction of an RNA with its cognate binding proteins, thereby providing another layer of regulation to control RNA fate. One important implication of these studies is that m6A does not just affect the function of readers that directly bind to the m6A site. Rather, it seems likely that certain m6A-dependent cellular processes (such as decay of some mRNAs in the cytoplasm) could be mediated by m6A through indirect routes (such as altering RNA structure) that affect factors other than the m6A readers themselves.

All mRNAs contain the RRACH consensus motif, but only a fraction of cellular mRNAs seem to be targeted for methylation [13, 32]. Data from MeRIP-Seq show that individual m6A peaks exhibit markedly distinct extents of m6A modification, indicating that transcripts from a given gene can be modified at different sites and to different extents [13, 32]. Using a newly developed method termed m6A-level andisoform-characterization sequencing (m6A-LAIC-seq) to better quantify the m6A levels across the transcriptome, a recent study [33] found that cells exhibit a wide range of nonstoichiometric levels of m6A in a cell-type specific manner. Thus, studies of the effects of m6A on mRNA decay so far have actually used pools of transcripts with heterogeneous extents of m6A modifications, including non-methylated transcripts. While current studies have shed light on some functions of m6A, to get further insight into the mechanisms by which m6A regulates RNA fate, it will be necessary to monitor the degradation of transcripts as a function of their extent of m6A modification. Moreover, it remains unclear as to what targets particular mRNAs for m6A modification. It is possible that the factors determining whether an mRNA will be subjected to m6A modification are the trigger that helps divert an mRNA into m6A-regulated pathways, such as mRNA turnover.

Varying 3’UTR length via alternative polyadenylation

Processing and polyadenylation of the 3’ end influences many aspects of mRNA metabolism, including pre-mRNA splicing, transcription termination by RNA polymerase II, mRNA export to the cytoplasm, mRNA stability, mRNA localization, and translation [8, 34, 35]. Advanced sequencing technologies (e.g., refs [36–38]) have revealed that alternative 3’ end processing and polyadenylation (APA) is widespread in mammalian cells, is regulated during development and differentiation, and can be dysregulated in disease [7, 8]. Over half of human genes encode multiple transcripts resulting from APA [36, 37, 39]. The most common form of APA is termed 3’UTR-APA or UTR-APA (Box 2). In this section, we focus on a few recent studies of the link between APA and mRNA turnover and also discuss how UTR-APA impacts the transcriptome through altered global mRNA stability.

Box 2. 3'UTR alternative processing and polyadenylation (UTR-APA).

UTR-APA is the most common form of APA and involves differential use of alternative polyadenylation sites located within the same terminal exon [8]. This frequently results in multiple transcripts (isoforms) with 3’ UTRs of different length but encoding the same protein. Many tissue- and biological process-specific instances of global APA have been reported. For example, in brain and nervous tissues, mRNA transcripts tend to use poly(A) sites that are distal to the stop codon, leading to mRNA isoforms with longer 3’ UTRs [77, 78]. In contrast, transcripts in tissues such as retina and placenta tend to use poly(A) sites that are proximal to the stop codon, resulting in shorter 3’UTRs. Therefore, mRNA 3′ end formation, and thus APA, is subject to dynamic regulation under diverse physiological conditions [7, 8].

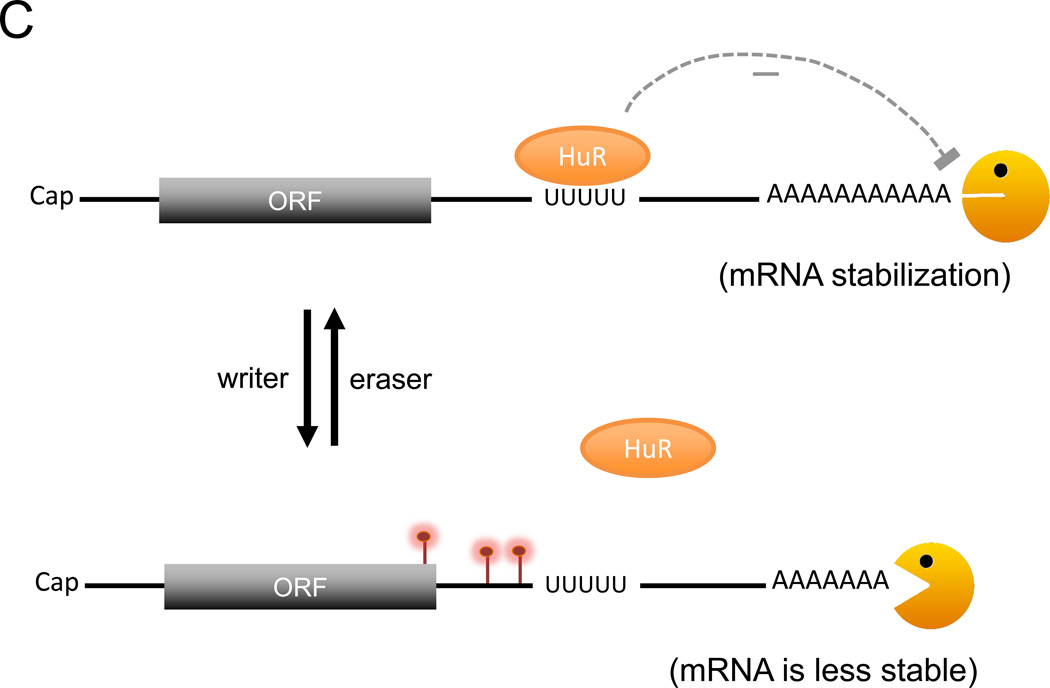

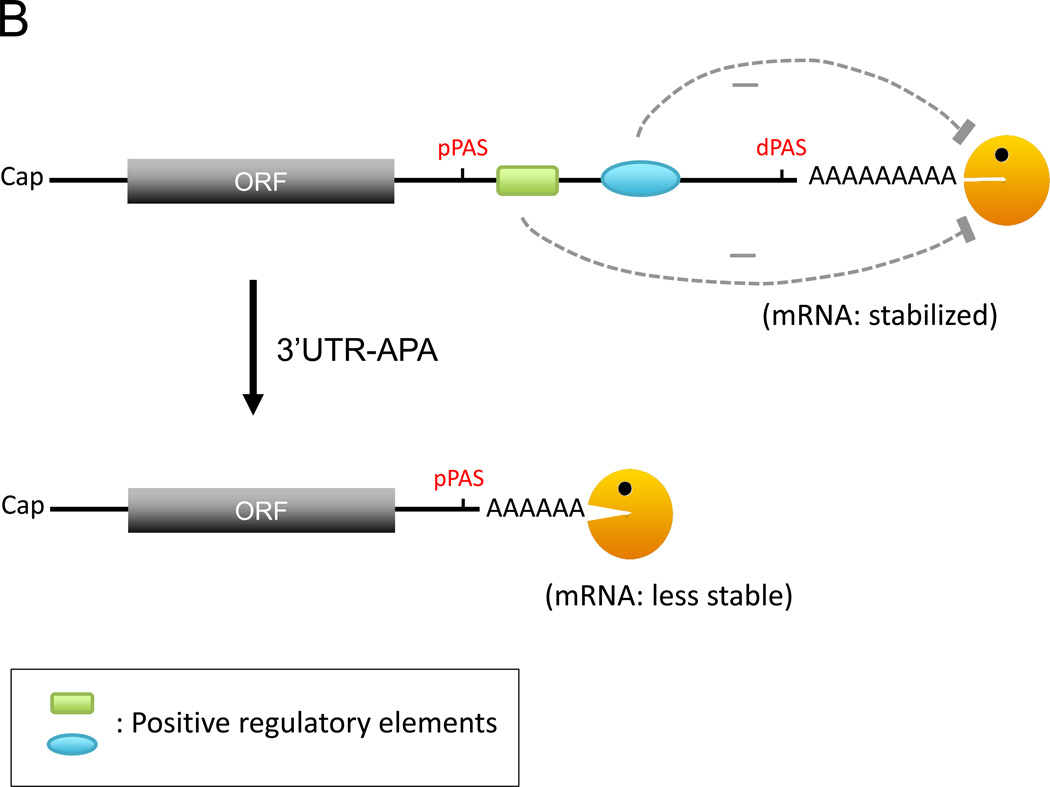

The 3’ UTRs of mRNA harbor a plethora of RNA regulatory elements and also serve as a binding target for many different RBPs [40, 41]. Binding of RBPs to these elements can control various characteristics of the bound mRNA transcripts, such as stability, localization and translation in the cytoplasm [42–46]. It is therefore no surprise that anomalies in the mRNA 3’UTR are linked with many human diseases [47, 48]. The UTR-APA process, via the choice of proximal versus distal poly(A) sites, can produce mRNA isoforms that either contain or lack a full array of cis-regulatory elements in the 3' UTR (Fig. 2) [7, 8]. This evident potential for impact on gene expression has driven recent attention on the UTR-APA process.

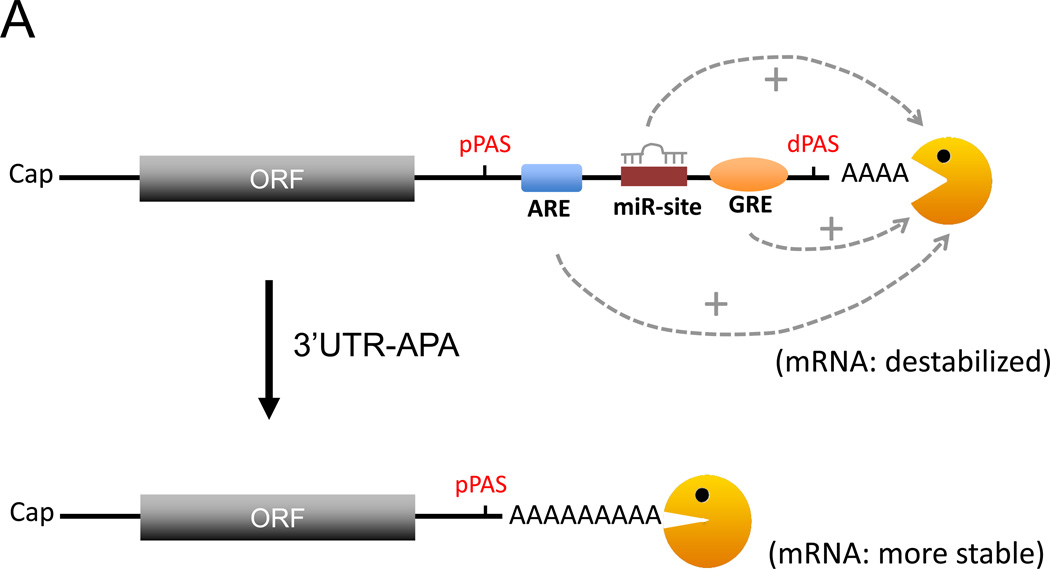

Figure 2.

Models of how the choice between a proximal poly(A) site (pPAS) and a distal poly(A) site (dPAS) might affect mRNA stability. A. 3’UTR-APA eliciting loss of the negative regulatory elements leads to mRNA stabilization. Depicted in the 3’UTR are a microRNA binding site (miR-site), an AU-rich element (ARE), and a GU-rich element (GRE), each frequently found in unstable transcripts. B. When 3’UTR-APA elicits loss of positive regulatory elements, the mRNA is less stable. Depicted in the 3’UTR are two RNA stabilizing elements assumed to block deadenylase complex access to the poly(A) tail. Orange Pac man: deadenylase complex.

The best-studied cis elements that control mRNA stability are miRNA binding sites and AREs [1, 42, 43, 45, 49]. ARE-binding proteins (ARE-BPs; such as AUF1/hnRNPD, TTP, or KSRP) and miRNA-associated factors (such as Ago and TNRC6 proteins) help recruit deadenylases and/or decapping enzymes to promote rapid degradation [50–52]. As longer 3’ UTRs will likely possess more regulatory elements, shortening of 3’UTRs via APA may remove negative regulation by these elements and thus increase mRNA stability and protein production. Consistent with this notion, some studies of unstable transcripts reported that transcripts with shorter 3’ UTRs produce higher levels of protein [53, 54]. A recent study in HeLa cells showed that knocking down one of the 3’ end formation core factors, CFIm25, elicits extensive 3’UTR shortening and that 64% of the transcripts with shortened 3’UTRs have increased steady-state levels [38]. Furthermore, gene expression moderately but positively correlates with the number of AREs and miRNA target sites lost in the shortened 3’UTR [38].

Many proteins (including oncoproteins, cytokines, cell cycle regulators, and signaling proteins) whose levels need to be tightly controlled are encoded by labile transcripts carrying an ARE [1, 55]. It has been shown that UTR-APA and consequent changes in mRNA stability can be an effective mechanism to control the protein levels of proto-oncogenes [53]. The shorter 3’UTRs of several proto-oncogene transcripts were more stable than their corresponding long 3’UTR isoforms and produced more proteins. A similar pattern was seen in transcriptome-wide studies focusing on shortening of long 3’UTR isoforms enriched in negative regulatory elements [53, 56, 57]. Transcripts retaining long 3’UTRs that contain predominantly destabilizing elements, such as the Puf-binding motif or AREs, tended to have faster decay rates in NIH3T3 cells or yeast [56–58].

Transcriptome-wide analyses of alternative 3’UTR isoforms also revealed that the 3’UTR regions lost in the shortened isoforms are usually enriched in conserved binding sites for miRNAs [59, 60]. As 3’UTR isoform ratios are highly cell-type specific [60, 61], cell type-specific gene regulation can be partially accomplished by miRNA-mediated mRNA decay through the interplay of alternative 3’UTR isoform expression, miRNA expression, and the presence of miRNA-binding sites in distal 3’UTRs. A cell type-specific increase in usage of proximal polyadenylation sites can thus be used to avoid regulation by miRNAs whose recognition sites are found in distal 3’UTRs. The idea of escaping from miRNA-mediated regulation as a means for cell type-specific regulation was supported by a transcriptome-wide study of several cell lines, showing that ~10% of predicted miRNA target sites were affected by the expression of alternative 3’UTRs [61].

As both activating and repressive elements can be present in 3’UTRs [62], shortening of 3’UTRs via APA can help escape both negative and positive regulation. Some recent studies in mammalian cells found either no correlation or only a weak correlation between shortened 3’UTRs and increased mRNA steady-state levels [38, 56, 57, 63]. A study in yeast using MIST-seq (Measurement of Isoform-Specific Turnover using Sequencing) that monitors the decay of individual mRNA isoforms in a genome-wide and strand-specific manner reached a similar conclusion [56]. As many elements with positive effects on gene expression are found in the 3’UTR [58, 62], these seemingly contradictory results of transcriptome-wide studies of APA and their effects on mRNA levels, stability, or protein levels in fact are not at odds with each other. For example, some RBPs, which recognize different positive or negative regulatory elements in the 3’UTRs and thus help execute their functions in mRNA turnover, may be expressed in one specific cell type under a particular cellular condition but not the other. As a result, the summation of effects on mRNA population caused by deleting both positive and negative regulatory elements through 3’UTR shortening may be neutral, destabilizing or stabilizing at the transcriptome level. Thus, the role of UTR-APA in regulation of gene expression is more complex than previously thought.

Codon optimality

The processes of mRNA decay and translation can be closely coupled [2, 64]. There are several specific decay pathways, particularly for surveillance or quality control purposes, whose actions to eradicate aberrant transcripts require translation of these mRNAs; specifically, they require ribosomes to traverse the transcript’s open reading frame (ORF) [65]. These include the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), no-go decay (NGD), and non-stop decay (NSD) pathways. In addition, RNA destabilizing elements also can be found in the ORF of normal transcripts (e.g., c-fos, c-myc, and tubulin mRNAs), and translation by ribosomes through the protein-coding-region elements of these mRNAs elicits their rapid decay [66–68]. While the link between mRNA decay and translation has been evidently demonstrated in particular cases, the relationship between mRNA decay and the translation process in general across the transcriptome is less clear.

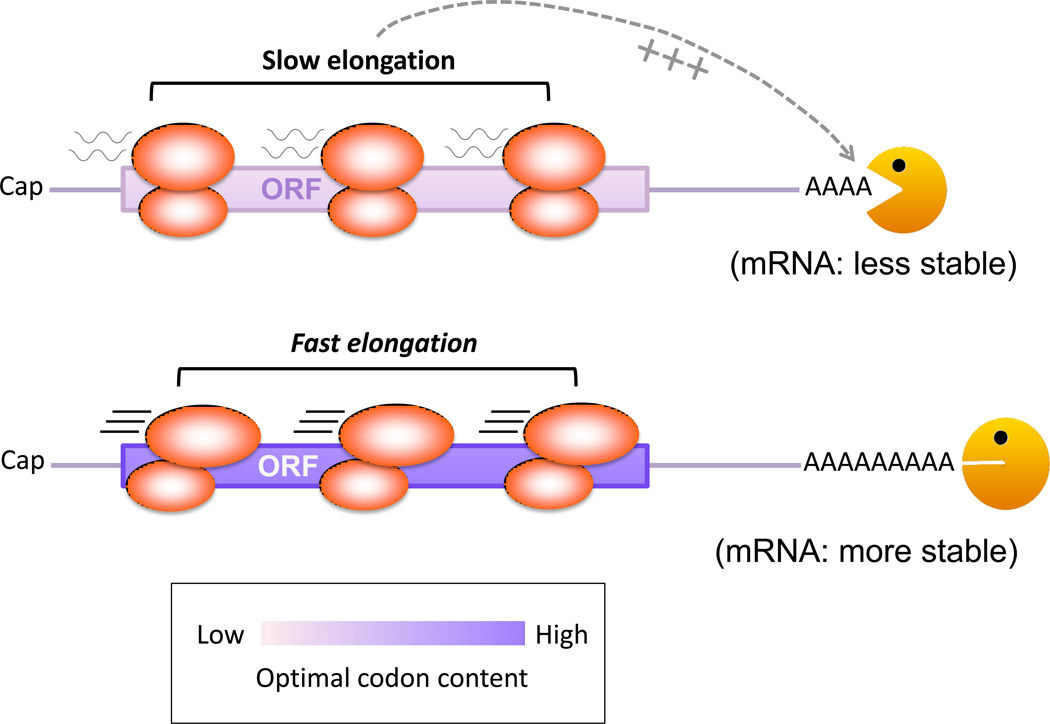

A recent study in yeast found that a full range of mRNA half-lives, from a few minutes to an hour, can be achieved without introducing any regulatory changes or elements outside of the ORFs and without altering peptide sequence of a transcript [9]. The results indicated that codon usage or optimality (Box 3) helps set the intrinsic decay rate of mRNA by linking it to translation across the transcriptome. Codon selection is under significant evolutionary pressure, with cells preferring to express tRNAs at levels tightly coordinated with relative demands of codon usage [69, 70]. The tRNAs decoding the codons that are evolutionarily enriched in highly translated mRNA transcripts are often of relatively higher abundance. By contrast, codons that exhibit no such selective bias are typically non-optimal, and are decoded by tRNAs of relatively lower abundance. Several lines of evidence indicate that it is the balance of optimal vs. non-optimal codons in the ORF rather than the presence of any particular codon that determines mRNA stability [9]. For example, the occurrence of individual very rare codons did not seem associated with a broad reduction in stability. Rather, transcripts with a high percentage of non-optimal codons are relatively unstable whereas messages with a high percentage of optimal codons are relatively stable, (Fig. 3). As codon optimality-linked regulation occurs through the ORF, it can act in parallel with other regulatory elements residing in the UTRs. Moreover, degradation regulated by codon optimality occurs through the deadenylation-dependent 5’–3’ mRNA decay pathway (Fig. 3) and is independent of the surveillance decay pathways such as NMD, NGD and NSD pathways for eradicating aberrant transcripts, even though those pathways are also coupled to translation [65].

Box 3. Codon optimality and bias.

The term “codon optimality” [79, 80] was introduced to better define the concept of differential recognition of codons by the ribosome (the translational apparatus). In other words, codon optimality is a measure of which codons are translationally optimal or efficient in a species based on “tRNA supply and demand” arguments [79, 80]. Thus, it is a spin-off of the earlier concept of codon usage bias; namely, the observation that different codons are preferentially used in different species, based on the frequency at which individual synonymous codons occur in protein coding DNA within the species' genomes [81–83]. The tRNA Adaptive Index (tAI) [84], measuring how efficiently a codon or its cognate tRNA is used by translating ribosomes, is considered as a classic metric of translation efficiency. However, the tAI does not reflect the cellular tRNA dynamics, which are driven by the balance between tRNA supply (the level of an individual tRNA) and tRNA demand (the abundance of the cognate codon in the transcriptome). Thus, a translational efficiency scale that reflects the dynamic balance has been proposed; this further normalizes for cellular tRNA abundances and selective constraints on codon-tRNA interactions [80]. There has been some work showing that codon selection is under significant evolutionary pressure, with cells tending to express tRNAs at levels that are tightly coordinated with relative demands of codon usage [69, 70]. Based on the normalized translational efficiency (nTE) scale, the tRNAs decoding the codons that are evolutionarily enriched in highly expressed mRNA transcripts are often of relatively higher abundance, whereas those decoding the codons that exhibit no such selective bias (which are typically non-optimal) are often of relatively lower abundance. In the nTE scale, codons are considered optimal if the relative availability of cognate tRNAs exceeds their relative usage.

Figure 3.

Model of two mRNAs with high and low codon optimality, respectively, differ in the traversing rate of their associated ribosomes. Note that ribosome loading or density may not be different between the two transcripts. Ribosomes traverse the ORF faster in the transcript with higher codon optimality (purple). Low codon optimality (light purple) triggers rapid deadenylation, followed by decapping and 5’ to 3’ digestion of RNA body (not depicted). The mechanism that senses the elongation rate and conveys it to the decay machinery is currently unknown. Pac man: deadenylase complex.

What is the underlying mechanism by which the codon optimality of an mRNA influences its stability? What are the relationships among codon optimality, translation rate, and stability of a transcript? On the one hand, results of polysome profiling (Box 4) showed no significant difference in ribosome density between mRNAs with high or low codon optimality [9]. On the other hand, results from in vitro ribosome run-off assays (Box 4) showed that upon inhibition of translation initiation and induction of ribosome run-off, a large portion of the mRNAs with a high percentage of optimal codons is relocated to the ribosome-free fractions of the gradient, whereas mRNAs with low codon optimality remain undisturbed in the polyribosomal fractions [9]. These observations strongly suggest that ribosomes traverse the ORF faster in transcripts with higher codon optimality (Fig. 3). Therefore, the link between codon translation rates and the concentration of the corresponding tRNA may provide an additional layer of gene regulation at the level of mRNA turnover. It is possible that codon optimality represents a general mechanism intrinsic to all mRNAs in yeast to fine-tune gene expression to mRNA stability and translation rates,

Box 4. Polysome profiling and ribosome run-off.

Polysome profiling is a protocol using sucrose density gradient centrifugation to separate polysomes from monosomes, ribosomal subunits, and messenger ribonucleoprotein particles (e.g., see ref [85]). This enables discrimination between efficiently translated mRNAs (in denser polysomes with more ribosomes) from poorly translated mRNAs (in less dense polysomes with fewer ribosomes). Before loading on the gradient, cytosolic extracts with mixed polysomes are stabilized by treatment with a translation elongation inhibitor such as cycloheximide, immobilizing each ribosome on the mRNA it is currently translating. After centrifugation, the gradient is divided into fractions of increasing density. Each fraction is treated to disrupt the polysomes and isolate the mRNAs from each fraction. Northern Blotting or quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) are typically used to determine the levels of mRNAs in each fraction. The resulting profile of individual mRNAs' abundance as a function of polysome density can be used to monitor changes in the translation efficiency of target mRNAs between different conditions.

Ribosome run-off measurements are performed by blocking translation initiation and monitoring the ribosomal occupancy of mRNAs (by density gradient fractionation) as ribosomes progress through elongation and termination over a given period of time [86]. The density gradient separates rapidly translated mRNAs (barely associated with polysomes) from slowly translated mRNAs (remain associated with polysomes). Thus, the run-off assay measures how quickly ribosomes finish elongation once initiated on targeted transcripts.

An important mechanistic implication of current observations concerning the codon optimality-directed mRNA decay is that there must be a mechanism to sense the overall speed of ribosomes traversing an ORF and decide how quickly that mRNA should be degraded. In yeast, codon optimality apparently serves to establish the base decay rate and expression level for a given mRNA, although there are outlier mRNAs that do not follow the pattern. Overall, an important implication from the current codon optimality studies is that it might be possible to reprogram the transcriptome in response to intra- or extra-cellular cues by modulating levels of tRNA pools.

Concluding Remarks

Several lines of evidence support the idea that the m6A modification system, APA, and the codon usage and optimality each contribute to shaping the mRNA stability profile across the transcriptome. However, investigation of each of these three cis-acting processes has challenges that must be overcome before the impact of the processes on mRNA stability can be properly evaluated (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions Box.

What are the regulatory elements and cognate binding proteins of a specific 3’UTR, and how do the interactions between the RNA regulatory elements and the corresponding binding proteins differ in mRNA isoforms resulted from UTR-APA?

Does codon optimality play a significant role in determining the intrinsic rate of mRNA decay in higher eukaryotes, where mRNAs carry many more regulatory elements than in yeast,?

What is the mechanism by which an ORF's codon optimality influences its overall translation elongation rate, and how does that signal mRNA stability change?

Given that most m6A modifications are found immediately upstream and/or downstream of stop codon in the mRNA 3’UTR, does m6A modification contribute to alternative 3’ end processing and polyadenylation, e.g., by preventing the usage of proximal poly(A) sites or conversely by favoring its use? Similarly, could APA also have a causal effect on m6A modification around the stop codon?

Across the transcriptome, mRNAs containing the RRACH methylation motif are much more common than mRNAs actually carrying m6A modification. This makes it likely that other cis-acting processes help determine an mRNA's susceptibility to methylation. Identifying such processes will be key to ultimately deciphering the mechanism of methylation specificity in cells and thus its effects on the fate of cytoplasmic mRNAs. Besides binding interactions with direct m6A readers (such as the YTHTF family of proteins), m6A modification can also influence mRNA decay via proteins that do not directly bind m6A. Identification of such "indirect readers" will no doubt provide useful new insight into the regulation of mRNA by m6A modifications.

Shortening of 3’UTRs by APA has in general been considered a way to escape negative regulation involving 3’UTR elements, thereby resulting in mRNA stabilization and increased protein production. One has to bear in mind that not every mRNA transcript contains miRNA binding sites in its 3’UTR, and that miRNAs represent only one class of regulatory elements that can enhance the decay of mRNA targets [71–73]. Likewise, the ARE, while much more potent than miRNA to destabilize mRNA, is found in the 3’UTR of only 10 –15% of the mammalian transcriptome [74]. Further, some ARE-BPs are associated with mRNA stabilization [75], and some 3'UTR elements have positive effects on gene expression [58, 62]. All of this points to broader and more complex functions of APA regulation.

An important technical challenge is the measurement of mRNA decay rates of individual 3’UTR mRNA isoforms in mammalian cells. The 3’-sequencing methods used to correlate differences in poly(A) site selection with differences in steady-state levels of mRNA are usually not sufficiently quantitative. The standard RNA-sequencing method coupled with bioinformatics tools does provide quantitation of separate 3’UTR isoforms but carries increased noise due to lower read counts at later time points for unstable mRNAs, making it more error-prone. A recently developed method, termed MIST-seq (Measurement of Isoform-Specific Turnover using Sequencing), represents an advancement in monitoring the decay of individual mRNA isoforms in a genome-wide and strand-specific manner [56]. Another future challenge for complete understanding of UTR-APA effects on mRNA stability is to develop an integrated approach to fully decipher the repertoire of 3’UTR regulatory elements and their cognate binding proteins and thus understand their functional status.

Much of our understanding of codon optimality comes from studies of simple cellular models. In a more complex organism with a multitude of cellular programs ranging from developmental roles to maintenance of mature tissues, the preferred set of codons could vary widely, depending on tRNA expression patterns and cellular function at the time (see Outstanding Questions). One issue is how to define the codon optimality in higher eukaryotes and thus its impact on mRNA stability. The evolution of multiple RNA regulatory elements in the 3’UTR of higher organisms brings another challenge, namely, how to discriminate between RNA destabilization resulting from high non-optimal codon content and that due to RNA destabilizing elements such as an ARE or a GU-rich element [44].

Studies of mRNA turnover in recent years have progressed from monitoring individual transcripts of interest to profiling global changes in mRNA stability under different cellular conditions. Several mechanisms for controlling global mRNA stability have already been identified. A major challenge going forward will be to determine how much each mechanism contributes to the global differences in mRNA stability observed under different cellular conditions or between different cells (Figure 4, Key Figure). Moreover, recent observations that non-methylated and m6A modified mRNA isoforms tend to use the distal and proximal poly(A) site, respectively [33, 76] suggest an interplay between m6A and APA pathways. It will also be important to elucidate how the three cis-acting mechanisms discussed here (Figure 4, Key Figure) act in concert to reprogram the transcriptome when cells respond to extra- and intra-cellular stimuli, or undergo differentiation and growth.

Figure 4.

Key Figure: Three cis-acting molecular processes that may influence the intrinsic stability of eukaryotic mRNA under cellular conditions. While m6A modification (I) and APA (II) occur post-transcriptionally in the nucleus, the optimal codon content (III) of an ORF is encoded by the gene. The use of a proximal poly(A) site results in mRNA with a short 3’UTR (constitutive UTR or cUTR) by shortening of the longer 3’UTR (alternative UTR or aUTR). Thus, UTR-APA events are often accompanied by loss of RNA regulatory elements present in the aUTR. For the effect of codon optimality on mRNA stability to be triggered, a transcript must let ribosomes traverse the ORF. The summation of the final extent of m6A modification, the choice between a proximal poly(A) site (pPAS) and a distal poly(A) site (dPAS), and the optimal codon content of a transcript helps set its intrinsic decay rate in the cytoplasm.

Trends Box.

The number of protein-encoding genes has remained relatively constant during evolution, but mRNA isoforms, codon usage bias, and post-transcriptional modifications have increased substantially, resulting in changes of mRNA turnover across the transcriptome.

The 3' UTRs of many protein-coding genes harbor multiple polyadenylation signals that are differentially selected based on the physiological state of cells, resulting in alternative mRNA isoforms with differing mRNA stability.

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant base modification in eukaryotic mRNA but many functional impacts of m6A on mRNA fate, mRNA stability in particular, have been discovered only recently.

Codon usage in mRNAs' open-reading frame influences gene expression, with the proportion of optimal and non-optimal codons helping to fine-tune mRNA stability in a process that is coupled to translation.

Acknowledgments

Owing to space limitations, many important contributions related to the topics discussed could not be cited. We thank R. Kulmacz for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM046454 to A.-B.S.) and by the Houston Endowment, Inc. (to A.-B.S).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen AC-Y, Shyu A-B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilusz CW, et al. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nature Reviews Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beelman CA, Parker R. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes. Cell. 1995;81:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu N, et al. A broader role for AU-rich element-mediated mRNA turnover revealed by a new transcriptional pulse strategy. Nucl. Acids Res. 1998;26:558–565. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garneau NL, et al. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:113–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu N, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine-encoded epitranscriptomics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayr C. Evolution and Biological Roles of Alternative 3′ UTRs. Trends in Cell Biology. 2016;26:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Giammartino Dafne C, et al. Mechanisms and Consequences of Alternative Polyadenylation. Molecular Cell. 2011;43:853–866. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Presnyak V, et al. Codon Optimality Is a Major Determinant of mRNA Stability. Cell. 2015;160:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desrosiers R, et al. Identification of Methylated Nucleosides in Messenger RNA from Novikoff Hepatoma Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1974;71:3971–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia G, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer KD, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3' UTRs and Near Stop Codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz S, et al. High-Resolution Mapping Reveals a Conserved, Widespread, Dynamic mRNA Methylation Program in Yeast Meiosis. Cell. 2013;155:1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geula S, et al. mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue Y, et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes & Development. 2015;29:1343–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.262766.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maity A, Das B. N6-methyladenosine modification in mRNA: machinery, function and implications for health and diseases. FEBS Journal. 2016;283:1607–1630. doi: 10.1111/febs.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:430–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castello A, et al. Insights into RNA Biology from an Atlas of Mammalian mRNA-Binding Proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baltz Alexander G, et al. The mRNA-Bound Proteome and Its Global Occupancy Profile on Protein-Coding Transcripts. Molecular Cell. 2012;46:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato M, et al. Cell-free Formation of RNA Granules: Low Complexity Sequence Domains Form Dynamic Fibers within Hydrogels. Cell. 2012;149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramaswami M, et al. Altered Ribostasis: RNA-Protein Granules in Degenerative Disorders. Cell. 2013;154:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kedersha N, Anderson P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2007;431:61–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon I, et al. Phosphorylation-Regulated Binding of RNA Polymerase II to Fibrous Polymers of Low-Complexity Domains. Cell. 2013;155:1049–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitale RC, et al. Structural imprints in vivo decode RNA regulatory mechanisms. Nature. 2015;519:486–490. doi: 10.1038/nature14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roost C, et al. Structure and Thermodynamics of N6-Methyladenosine in RNA: A Spring-Loaded Base Modification. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2015;137:2107–2115. doi: 10.1021/ja513080v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu N, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu N, et al. Probing N6-methyladenosine RNA modification status at single nucleotide resolution in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA. 2013;19:1848–1856. doi: 10.1261/rna.041178.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molinie B, et al. m6A-LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m6A epitranscriptome. Nat Meth. 2016;13:692–698. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proudfoot NJ. Ending the message: poly(A) signals then and now. Genes & Development. 2011;25:1770–1782. doi: 10.1101/gad.17268411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutz CS, Moreira A. Alternative mRNA polyadenylation in eukaryotes: an effective regulator of gene expression. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA. 2011;2:22–31. doi: 10.1002/wrna.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepard PJ, et al. Complex and dynamic landscape of RNA polyadenylation revealed by PAS-Seq. RNA. 2011;17:761–772. doi: 10.1261/rna.2581711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoque M, et al. Analysis of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation by 3[prime] region extraction and deep sequencing. Nat Meth. 2013;10:133–139. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masamha CP, et al. CFIm25 links alternative polyadenylation to glioblastoma tumour suppression. Nature. 2014;510:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature13261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian B, et al. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:201–212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matoulkova E, et al. The role of the 3' untranslated region in post-transcriptional regulation of protein expression in mammalian cells. RNA Biology. 2012;9:563–576. doi: 10.4161/rna.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wissink EM, et al. High-throughput discovery of post-transcriptional cis-regulatory elements. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2479-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barreau C, et al. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucl. Acids Res. 2006;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N. The mechanics of miRNA-mediated gene silencing: a look under the hood of miRISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halees AS, et al. Global assessment of GU-rich regulatory content and function in the human transcriptome. RNA Biology. 2011;8:681–691. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.16283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller MA, Olivas WM. Roles of Puf proteins in mRNA degradation and translation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA. 2011;2:471–492. doi: 10.1002/wrna.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richter JD. CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conne B, et al. The 3' untranslated region of messenger RNA: A molecular 'hotspot' for pathology? Nat Med. 2000;6:637–641. doi: 10.1038/76211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JM, et al. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3' regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes I: general principles and overview. Hum Genet. 2006;120:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonas S, Izaurralde E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:421–433. doi: 10.1038/nrg3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Behm-Ansmant I, et al. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1885–1898. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoecklin G, et al. ARE-mRNA degradation requires the 5'-3' decay pathway. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:72–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandler H, et al. Not1 mediates recruitment of the deadenylase Caf1 to mRNAs targeted for degradation by tristetraprolin. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:4373–4386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayr C, Bartel DP. Widespread Shortening of 3'UTRs by Alternative Cleavage and Polyadenylation Activates Oncogenes in Cancer Cells. Cell. 2009;138:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandberg R, et al. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3' untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenberg ME, Belasco JG. Control of the decay of labile protooncogene and cytokine mRNAs. In: Belasco JG, Brawerman G, editors. Control of messenger RNA stability. Academic Press; 1993. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gupta I, et al. Alternative polyadenylation diversifies post-transcriptional regulation by selective RNA–protein interactions. Molecular Systems Biology. 2014;10 doi: 10.1002/msb.135068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spies N, et al. 3′ UTR-isoform choice has limited influence on the stability and translational efficiency of most mRNAs in mouse fibroblasts. Genome Research. 2013 doi: 10.1101/gr.156919.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geisberg Joseph V, et al. Global Analysis of mRNA Isoform Half-Lives Reveals Stabilizing and Destabilizing Elements in Yeast. Cell. 2014;156:812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelechano V, et al. Extensive transcriptional heterogeneity revealed by isoform profiling. Nature. 2013;497:127–131. doi: 10.1038/nature12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lianoglou S, et al. Ubiquitously transcribed genes use alternative polyadenylation to achieve tissue-specific expression. Genes & Development. 2013;27:2380–2396. doi: 10.1101/gad.229328.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Derti A, et al. A quantitative atlas of polyadenylation in five mammals. Genome Research. 2012;22:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gr.132563.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oikonomou P, et al. Systematic Identification of Regulatory Elements in Conserved 3′ UTRs of Human Transcripts. Cell Reports. 2014;7:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gruber AR, et al. Global 3′ UTR shortening has a limited effect on protein abundance in proliferating T cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacobson A, Peltz SW. Interrelationships of the pathways of mRNA decay and translation in eukaryotic cells. Annual Review Biochem. 1996;65:693–739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Graille M, Seraphin B. Surveillance pathways rescuing eukaryotic ribosomes lost in translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:727–735. doi: 10.1038/nrm3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grosset C, et al. A mechanism for translationally coupled mRNA turnover: Interaction between the poly(A) tail and a c-fos RNA coding determinant via a protein complex. Cell. 2000;103:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wisdom R, Lee W. The protein-coding region of c-myc mRNA contains a sequence that specifies rapid mRNA turnover and induction by protein sythesis inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1991;5:232–243. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yen TJ, et al. Autoregulated instability of beta-tubulin mRNAs by recognition of the nascent amino terminus of beta-tubulin. Nature. 1988;334:580–585. doi: 10.1038/334580a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yona AH, et al. tRNA genes rapidly change in evolution to meet novel translational demands. eLife. 2013;2:e01339. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doherty A, McInerney JO. Translational Selection Frequently Overcomes Genetic Drift in Shaping Synonymous Codon Usage Patterns in Vertebrates. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30:2263–2267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo H, et al. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen C-YA, et al. Ago-TNRC6 triggers microRNA-mediated decay by promoting two deadenylation steps. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1160–1166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fabian MR, et al. Mammalian miRNA RISC Recruits CAF1 and PABP to Affect PABP-Dependent Deadenylation. Molecular Cell. 2009;35:868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bakheet T, et al. ARED 3.0: the large and diverse AU-rich transcriptome. Nucl. Acids Res. 2006;34:D111–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ke S, et al. A majority of m6A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3′ UTR regulation. Genes & Development. 2015;29:2037–2053. doi: 10.1101/gad.269415.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang H, et al. Biased alternative polyadenylation in human tissues. Genome Biology. 2005;6:1–13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Licatalosi DD, et al. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou T, et al. Translationally Optimal Codons Associate with Structurally Sensitive Sites in Proteins. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2009;26:1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pechmann S, Frydman J. Evolutionary conservation of codon optimality reveals hidden signatures of cotranslational folding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:237–243. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grantham R, et al. Codon catalog usage is a genome strategy modulated for gene expressivity. Nucleic Acids Research. 1981;9:r43–r74. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.1.213-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maruyama T, et al. Codon usage tabulated from the GenBank genetic sequence data. Nucleic Acids Research. 1986;14:r151–r197. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.suppl.r151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sharp PM, Li WH. The codon Adaptation Index--a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Research. 1987;15:1281–1295. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reis Md, et al. Solving the riddle of codon usage preferences: a test for translational selection. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:5036–5044. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mašek T, et al. Polysome Analysis and RNA Purification from Sucrose Gradients. In: Nielsen H, editor. RNA: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 293–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coller J, Parker R. General translational repression by activators of mRNA decapping. Cell. 2005;122:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]