Abstract

Background:

Diabetes disease is one of the 4 main types of non-communicable diseases. No research has been conducted in order to identify data items for Diabetic Personal Health Record (DPHR), in Iran. This study, with the aim of systematically developing the DPHR was done to supply ultimately the country with a national model through Delphi method.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of the literature using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Web of sciences, Scopus, Science Direct, and ACM digital library. The year of the study included the obtained articles was 2013. We used a 3-step method to identify studies related to DPHR. Study selection processes were performed by two reviewers independently. The eligible studies were included in this review. Quality of studies was assessed using a mixed approach scoring system. Reviewers used 2-step method for the validation of the final DPHR model.

Results:

Initially, 2011 papers were returned from online databases and 186 studies from gray literature search. After removing duplicates, study screening, and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 129 studies were eligible for further full-text review. Considering the full-text review, 34 studies were identified for final review. Given the content of selected studies, we determined seven main classes of DPHR. The highest score belongs to home monitoring data class by mean of 19.83, and the lowest was general data class by mean of 3.89.

Conclusion:

Together with representative sample of endocrinologist in Iran achieved consensus on a DPHR model to improve self-care for diabetic patients and to facilitate physician decision making.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, Personal health record, Systematic review, Self-care, Iran

Introduction

Diabetes disease is one of the 4 main types of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (1) and its management is of important concern to the world at large (2–4). According to the definition of International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (5): “Type 2 diabetes is a chronic disease that characterized by relative insulin deficiency and insulin resistance, either or both of present at the when disease is diagnosed.”

The major consequences of inattention or inadequate attention to treatment of diabetes include nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, neuropathy, etc. (6). Blood glucose monitoring, regular visits, physical activities, blood pressure monitoring, blood lipids control and periodical examinations can help lessen these complications (7, 8), and these are the foundation of self-care related to diabetes management (9).

The past decades have been witness to a steady increase in the number of diabetic patients. The increase in the prevalence of this medical condition can be observed across the world, but it has been more rapid in the undeveloped and developing countries (10). Iran is one of the 20 countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region classified by the IDF (11). Worldwide, 387 million people have diabetes, while more than 37 million people in the MENA region have diabetes, with an estimated increase of 68 million by 2035. In Iran, there were over 4.5 million cases of diabetes in 2014 (11). In addition, in 2014, the prevalence of diabetes worldwide and in Iran was estimated to be 9% (12) and 8.6% (11), respectively. Therefore, diabetes mellitus management is one of the greatest health system challenges facing Iran.

In order to manage the increasing number of diabetes disease in the future (13, 14) and reduce the workload of healthcare settings, there is the need to redefine the role of diabetes management organizations (15). Patients having more knowledge about the disease and its process are more proficient during communication, thus acting as helpful assets in the long-term care (16). Therefore, a Web-based Personal Health Record (PHR) will serve as a useful tool in providing patients with easy access to their health information (17–19).

In the last decade, PHRs has been widely used to provide diabetic patients with proper set of information needed for their care, and accessibility to their health information (17, 18, 20). Various definitions for PHR have been presented by numerous organizations (21, 22). The Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) defines PHR (21): “as a universally accessible, layperson comprehensible, lifelong tool for managing relevant health information, promoting health maintenance and assisting with chronic disease management via an interactive, common data set of electronic health information and e-health tools”.

In addition, a broad range of literature has emphasized active participation of patients in their care processes. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted patient active participation in optimal care (23). It considers patients as one of the main pillars of care concept, along with health care professionals, direct-care workers, informal care-givers (usually family and friends), and emphasizes a share of the essential data, knowledge, and tools to ensure high-quality care. Likewise, patients’ participation in disease management is found to be tightly associated with their empowerment and potential cost-saving (24).

The benefits of PHR in supporting self-care cannot be overemphasized, especially in facilitating communications among health care settings and supporting information access (25). In Iran, to best of our knowledge, no research has been conducted in order to identify data items for Diabetic Personal Health Record (DPHR). This study, with the aim of systematically developing the DPHR was done to supply ultimately the country with a national model through Delphi method.

Methods

Study identification

A systematic review of the literature was conducted using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Web of science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) digital library. The year of the study included the obtained articles was 2013.

A 3-step approach was used for this study: A) In the first step, the above-mentioned databases were searched to identify papers related to DPHR; B) the reference lists of included papers were hand-searched to identify additional relevant studies; and C) in the last step, we boosted our search strategy by searching gray literatures including reports, standards, manuals, and guidelines related to DPHR through general search engines such as Google to collect extra potential relevant evidences. In order to maximize the power of aggregation, the search was limited to type 2 diabetes. No date or study design limitation was imposed; however, studies not written in English were excluded.

Initial search strategy terms included variations of PHR concept (PHR, Personal EMR, Personal EHR, Portable EMR, Portable EHR, Personal CPR, Portable CPR, Portable Health Record*, Portable medical Record*, Personal Health Card*, Personal Medical Card*, Portable Health Card*, Portable Medical Card*, Personal Health Record*, Personal Medical Record*, Personal Electronic Health Record*, Personal Electronic Medical Record*, Portable Electronic Health Record*, Portable Electronic Medical Record*, Personal Computerized Patient Record*, Portable Computerized Patient Record*) and self-care concept (Self-Care, Self-Management, Self-Management, Self-Administration, Self-Administration, Patient Participation, Consumer Participation, Self-Monitoring, Self-Monitoring).

Using free text and MeSH term returned too many results. Therefore, the search was narrowed down through database options as outlined in Table 1. In all databases, the conjunction “AND”, disjunction “OR” and truncation operator “*” were utilized. Electronic databases queries are available upon request.

Table 1:

Detailed search strategy related to electronic databases

| Database | Timespan | Search fields | Reference Type | Language | Returns | Access date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | All yr | Title/ abstract | All references | English | 543 | Week 2 December 2013 |

| Web of science | All yr | Topic | All references | English | 448 | Week 2 December 2013 |

| ScienceDirect | All yr | All fields | All references | English | 550 | Week 2 December 2013 |

| Scopus | All yr | All fields | All references | English | 184 | Week 2 December 2013 |

| ACM Digital Library | All yr | Anywhere except full text | Peer reviewed and full text | English | 286 | Week 2 December 2013 |

Search strategy development and study screening

After developing the methods of study identification, source selection, and search combinations, one reviewer (A.A.), performed the search for the literature. Then, all the search strategy returns were exported into the reference management software, EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). The studies returned because of this search were screened and compared with the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two independent reviewers (A.A. and B.H.). Any disagreements were reconciled with the third reviewer (M.T.). He was also responsible for the supervision of the project.

Eligibility criteria

Each study was assessed independently by two reviewers for eligibility criteria. The studies included in this review met the following criteria:

The type of record: paper or electronic chart, sheet, notes, diary

Target person or user: known diabetic patient (of a clinic or hospital) and a diabetic consumer in general;

Type of diabetes: only type 2 diabetes

Exclusion criteria for DPHR were:

Type of record: should be not hospital based on medical record

Type of literature: not to be letter to editors, comments, position papers, unstructured papers, proceeding papers, thesis and dissertation

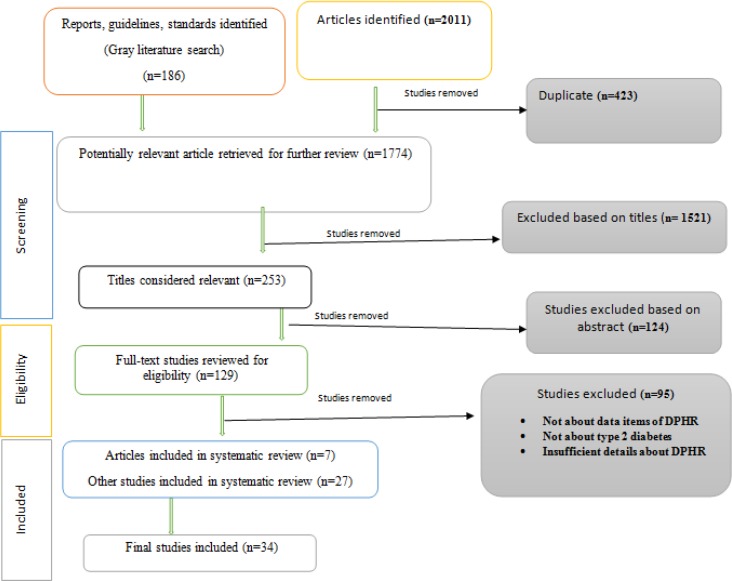

After checking for eligibility, the full text of qualified studies was obtained. The finally selected papers were read, tagged, and hand-noted by one reviewer (A.A.) and then verified by the second reviewer (M.T.). A brief flow diagram of the strategy is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1:

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies

Data extraction

Studies deemed eligible for review underwent data extraction by one reviewer. For each, essential data items related to DPHR were extracted into a form, including a set of properties: data element, data class, reference type, and citation resource. Some additional properties such as target value, and suggested measurement interval were also recorded when available and applicable.

Quality appraisal

Many approaches exist to appraise the overall quality of studies in systematic review. Owing to the diversity of studies including articles, guidelines, reports, and standards, we found no one-for-all appraisal tool to use. Therefore, quality of studies was assessed using a mixed approach scoring system as follows: A) American Diabetes Association (ADA) Evidence Grading System For Clinical Practice Recommendations (26); B) Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice, Evidence Rating Scale (27). Quality scores were assigned by one reviewer (A.A.) and verified by second reviewer (M.T.). In this approach, non-article studies such as reports, standards, and guidelines were considered as formal or expert consensus. The maximum score obtained for a DPHR-related data element was 51 points. The summary of our quality assessment approach is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2:

Evidence quality scoring system

| Evidence Type | Score |

|---|---|

| RCT, Meta-Analysis, Systematic Review | 4 |

| Case-Control, Cohort Study, Quasi-Experimental | 3 |

| Non-Analytic or Observational Studies (Case Report, Case Series) | 2 |

| Formal/ Expert Consensus | 1 |

Validation method

Researchers used a 2-step validation method through Modified Delphi technique in two rounds as follows: A) in the first round, the final data elements were assessed by nine local clinical experts (general characteristics of the samples are outlined in Table 3). Data elements to be included were decided based on the agreement quotient. In this way, data elements of more than 75% agreement quotient were picked from the primary round and were not passed to the second. The elements of 50% to 75% agreement were reassessed in the second round. The elements of below 50% were eliminated. In the first round, all data elements of DPHR obtain more than 75% agreement quotient, and therefore it limited one-step.

Table 3:

General characteristics of the clinical experts attended in the Delphi technique (n=9)

| Specialty | Gender | Age group (year) | Academic degree | Work experience (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrinology (n=8) | Male (n=2) | 30–40 (n=4) | Full professor (n=1) | <10 (n=4) |

| Internal medicine (n=1) | Female (n=7) | 40–50 (n=3) | Associate professor (n=2) | 10–20 (n=3) |

| 50–60 (n=1) | Assistant professor (n=6) | 20–30 (n=1) | ||

| >60 (n=1) | >30 (n=1) |

B) In the second round, clinical experts were requested to score each data element based on a 5-point Likert scale (1=least important; 5=highly important). Then, the median score for each data element was calculated. It was decided to pick only the data elements of more than 4 points median, to be included in the final DPHR design.

Results

Initially, 2011 papers were returned from online databases and 186 studies from gray literature search. After removing duplicates, study screening, and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 129 studies were eligible for further full-text review. Reviewing the full-text studies for final content match, only 34 were selected for the final review. Further details pertaining to included studies are shown in Fig. 1.

General characteristics of the clinical experts who performed the Delphi technique are detailed in Table 3. As outlined in the table, clinical experts age ranged from 35 to 67 yr, most of them (n=7, 78%) were male. Moreover, all but one (internist) were endocrinologists with a wide range of work experience from 3 to 37 yr. The degree was assistant professor or higher.

Considering the content of the included studies, seven main classes of DPHR were determined. Details relating to these classes, number of their data items and agreement quotient of Delphi technique is outlined in Table 4.

Table 4:

Data classes for a DPHR

| Data classes | Data elements numbers | Agreement quotient (%) | Selected numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 | 50–75 | >75 | |||

| General data | 11 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Home monitoring data | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Laboratory data | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Examination data | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Vaccination data | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient education data | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Drug data | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 48 | 1 | 0 | 47 | 47 |

Corresponding data items of each class with their scores calculated based on the sum of evidences’ quotients, after applying the Delphi technique, are detailed in Table 5. It is worthwhile to mention that these classes were arranged by relevance. Overall quality scores of each data item ranged from 1 to 51 points. The highest score belongs to home monitoring data class by a mean of 19.83, and the lowest was general data class by a mean of 3.89. The median scores given by the clinical experts are also included in Table 5. As earlier mentioned, data items of median score of four or higher were selected for the final DPHR model.

Table 5:

Scores of data elements of DPHR calculated based on sum of references quotients and the median of scores of data elements of DPHR assigned by clinical experts

| Data Class | Data Elements | References | Score | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General data | Record number | (39–41) | 3 | 5 |

| Date birth | (39, 42, 43) | 3 | 5 | |

| Gender | (43) | 1 | 5 | |

| Occupation | (43) | 1 | 4 | |

| Blood type | (43) | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Rh | (43) | 1 | 2 | |

| Address | (39, 42–47) | 9 | 2 | |

| Telephone | (39, 42–47) | 11 | 5 | |

| Emergency telephone | (42–50) | 11 | 4 | |

| Center telephone | (41, 47) | 2 | 4 | |

| Mean | 4.30 | |||

| Home monitoring data | Blood glucose monitoring | (39–41, 43–47, 49–59) | 31 | 5 |

| Blood pressure monitoring | (39, 41–45, 47–51, 53–57, 59–62) | 38 | 5 | |

| Weight | (39, 41–45, 47–49, 51–57, 61) | 28 | 5 | |

| Body Mass Index/ BMI | (42–44, 50, 53, 56, 61, 62) | 15 | 5 | |

| Waist circumference | (39, 43, 50, 53) | 4 | 4.5 | |

| Height | (42, 49, 53) | 3 | 3 | |

| Mean | 19.83 | |||

| Laboratory data | Glycated hemoglobin/ HbA1c | (39–45, 47–49, 51–58, 60–62) | 37 | 5 |

| Total cholesterol | (39–45, 48–51, 53–57, 59) | 28 | 5 | |

| Triglyceride | (39–45, 47, 49–51, 53–57) | 24 | 5 | |

| High-density lipoprotein/ HDL | (39–45, 47, 49–51, 53, 54, 56, 57) | 20 | 5 | |

| Low-density lipoprotein/ LDL | (39–45, 47, 49–51, 53, 54, 56, 57, 60–62) | 30 | 5 | |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone/ TSH | (40) | 1 | 5 | |

| Microalbuminuria | (39–43, 45, 49, 54–57, 61, 62) | 25 | 5 | |

| Urine glucose | (43) | 1 | 5 | |

| Proteinuria | (43, 44, 49, 51, 53, 55) | 9 | 5 | |

| Creatinine blood test | (39, 42, 44, 45, 49, 52, 54–56) | 16 | 5 | |

| Mean | 19.10 | |||

| Examination data | Foot examination | (39–45, 48, 49, 51, 53–57, 59, 61, 62) | 33 | 5 |

| Eye examination | (39–45, 48, 49, 51–54, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62) | 30 | 5 | |

| Dental exam | (33, 40, 41, 45, 48, 51, 53, 54, 56) | 9 | 4 | |

| Pulse | (39, 43, 55) | 6 | 5 | |

| Sensation | (39, 42, 43, 55) | 7 | 5 | |

| Mean | 17 | |||

| Vaccination data | Influenza vaccine/ Flu shot | (39–41, 45, 48, 51, 53, 54, 57, 61) | 15 | 4 |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | (40, 41, 45, 48, 54, 57, 62) | 10 | 3.5 | |

| Hepatitis B vaccine | (45, 48, 54) | 3 | 4 | |

| Mean | 17 | |||

| Patient education data | Smoking cessation | (44, 45, 52, 54, 56, 59, 61, 62) | 20 | 4 |

| Self-care education | (45, 48, 54) | 3 | 5 | |

| Life style | (52, 53) | 2 | 5 | |

| Mean | 8.33 | |||

| Drug data | Drug name | (39, 40, 42–44, 50, 51) | 7 | 5 |

| Reason for taking medication | (40, 50) | 2 | 5 | |

| Dose | (39, 40, 42–44, 50, 51) | 7 | 5 | |

| Times of taking medication | (40, 43, 44, 51) | 4 | 5 | |

| Prescription date | (39, 42–44, 50) | 5 | 5 | |

| Date of taking medication stop | (39, 42, 43) | 3 | 5 | |

| Reason of taking medication stop | (39, 42, 43) | 3 | 4 | |

| How long taking medication | (50) | 1 | 5 | |

| Other instructions (e.g. taking medication with food) | (39, 42, 50) | 3 | 4 | |

| Mean | 3.89 |

Selected data elements for the final DPHR are outlined in Table 6. As illustrated in the table, this model constitutes seven classes and 42 data elements. Moreover, data items of each class are also summarized in this table. Final model was developed after applying Delphi technique.

Table 6:

Selected data elements in final DPHR

| Data Class | Data Elements | Data Class | Data Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| General data | Record number | Examination data | Foot examination |

| Date birth | Eye examination | ||

| Gender | Dental exam | ||

| Occupation | Pulse | ||

| Telephone | Sensation | ||

| Emergency telephone | |||

| Center telephone | |||

| Home monitoring data | Blood glucose monitoring | Vaccination data | influenza vaccine/ Flu shot |

| Blood pressure monitoring | Hepatitis B vaccine | ||

| Weight | |||

| Body Mass Index/ BMI | |||

| Waist circumference | |||

| Laboratory data | Glycated hemoglobin/ HbA1c | Patient education data | Smoking cessation |

| Total cholesterol | Self-care education | ||

| Triglyceride | Life style | ||

| High-density lipoprotein/ HDL | |||

| Low-density lipoprotein/ LDL | |||

| Thyroid stimulating hormone/TSH | |||

| Microalbuminuria | Drug data | Drug name | |

| Urine glucose | Reason for taking medication | ||

| Proteinuria | Dose | ||

| Creatinine blood test | Times of taking medication | ||

| Prescription date | |||

| Date of taking medication stop | |||

| Reason of taking medication stop | |||

| How long taking medication | |||

| Other instruction (taking medication with food, …) |

Discussion

One of the countries with the highest prevalence of diabetes among population is Iran (28). According to the findings of a recent study, Iran’s healthcare system lacks any standard and structured scheme for the collection of data pertaining to diabetic patients (29). A DPHR can be the cornerstone of an effectual system for collection of diabetic data and organization of self-care for diabetic patients, and the absence of such system in Iran highlight the need for further work on this issue (30, 31).

This study is the first effort, to develop PHR system for diabetic patients in Iran. Systematic review of the evidences consists of articles, international reports, standards, manuals, and guidelines provided a basis for developing the initial DPHR. Since there was no standard DPHR model in Iran, hence, the systematic review was used in order to reach a preliminary model. A study, has suggested that to improve implementation, changes in the form and content of the PHRs are necessary (32).

The recent decade has been witness to growing application of PHRs and especially those pertaining to diabetes (30). In this study, we systematically reviewed literature for data elements of DPHR, and reassessed the results with the viewpoints of local clinical experts. This study utilizes the ideas of the significant number of the clinical specialist in the development and validation of DPHR tool for diabetic patients. For optimal management of diabetic disease, data should be organized in a standard manner at a local level. The validation of a systematic review findings corresponding to national context is suggested (33).

The results of reviewing the evidences revealed that the variations of categories in the final model identified by this review fall into seven distinct classes of data elements, as follows: general data, home monitoring data, laboratory data, examination data, vaccination data, patient education data, and drug data. Among these data classes, home monitoring data and drug data were among the most- and least-cited, respectively. Moreover, out of data items, address, telephone, and emergency telephone (general data), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, microalbuminuria, triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (laboratory data), blood pressure monitoring, blood glucose monitoring, and weight (home monitoring data), influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine (vaccination data), smoking cessation (patient education data), foot examination and eye examination (examination data), drug name and dose (drug data) were the most-cited while gender, occupation, blood type, and Rh (general data), waist circumference and height (home monitoring data), urine glucose, proteinuria, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) (laboratory data), dental exam, pulse, and sensation (examination data), hepatitis B vaccine (vaccination data), self-care education and lifestyle (patient education data), self-care education and lifestyle (patient education data), reason for taking medication, date of stopping medication, reason for stopping medication, and the duration of taking medication (drug data) were the least-cited. No similar studies in accordance with these findings were found.

The results of validation method showed that the majority of data items related to all seven classes were assessed as important and highly important by the clinical experts. Out of these data classes, laboratory and general data items were among the most- and least-weighted, respectively. The findings are consonant with other research in terms of the importance of data elements evaluated by the experts as minimum data set for cystic fibrosis registry (34), breast cancer (35), athlete health records (36), nursing (37), and information management system for orthopedic injuries (38).

A few factors limit the generalizability of our results. First, we did not contact the authors of the included studies to confirm the categorization of data items related to DPHR. However, we do not think that it would have changed the developed categorization. Second, scoring system for studies was conducted by one reviewer rather than two independent reviewers. However, assigned points were verified by the chief reviewer. Moreover, since the final DPHR Model was validated by Iranian clinical experts, caution is necessary for generalizability of these findings to other contexts.

Conclusion

A systematic review of evidences, together with representative sample of endocrinologist in Iran achieved consensus on a DPHR model to improve self-care for diabetic patients and to facilitate physician decision making. However, to benefit for patients and clinicians, the DPHR need to be implemented and evaluated in routine clinical practice. The final model developed by the reviewers will enable patients to participate actively in their treatment and will support physicians for optimal decision making for diabetic patients. Moreover, it will facilitate the communication between health care providers and patients.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This work was a part of the first author’s PhD dissertation in supported by a grant [grant # 921835] from Mashhad University of Medical Sciences Research Council. The funder was involved in preparation and publication process of manuscript. We would also like to thank all clinical experts of Mashhad Research Center of Metabolic Syndrome for their participation in DPHR model validation process. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2015). Noncommunicable diseases. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/.

- 2.Tani S, Marukami T, Matsuda A, Shindo A, Takemoto K, Inada H. (2010). Development of a health management support system for patients with diabetes mellitus at home. J Med Syst, 34 (3): 223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim S, Kim SY, Kim JI, Kwon MK, Min SJ, Yoo SY, et al. (2011). A survey on ubiquitous healthcare service demand among diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab J, 35 (1): 50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyles CR, Harris LT, Le T, Flowers J, Tufano J, Britt D, et al. (2011). Qualitative evaluation of a mobile phone and web-based collaborative care intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther, 13 (5): 563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Diabetes Federation (2016). About diabetes. http://www.idf.org/about-diabetes.

- 6.World Health Organization (2016). Complications of diabetes. http://www.who.int/diabetes/action_online/basics/en/index3.html.

- 7.Ruggiero L, Glasgow R, Dryfoos J, Rossi J, Rochaska J, Orleans C, et al. (1997). Diabetes self-management. Self-reported recommendations and patterns in a large population. Diabetes Care, 20: 568–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robiner W, Keel P. (1997). Self-management behaviors and adherence in diabetes mellitus. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry, 2: 40–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonda SJ, Kedziora RJ, Vigersky RA, Bursell SE. (2010). Evolution of a web-based, prototype Personal Health Application for diabetes self-management. J Biomed Inform, 43 (5 Suppl): S17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (2016). Global report on diabetes. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 11.International Diabetes Federation (2015). Iran vs world prevalence of diabetes. http://www.idf.org/membership/mena/iran.

- 12.World Health Organization (2014). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/.

- 13.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. (2010). Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 87 (1): 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baan CA, van Baal PH, Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, Verkley H, Poos MJ, Hoogenveen RT, et al. (2009). Diabetes mellitus in the Netherlands: estimate of the current disease burden and prognosis for 2025. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 153: A580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronda MC, Dijkhorst-Oei LT, Gorter KJ, Beulens JW, Rutten GE. (2013). Differences between diabetes patients who are interested or not in the use of a patient web portal. Diabetes Technol Ther, 15 (7): 556–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buettner K, Fadem SZ. (2008). The internet as a tool for the renal community. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis, 15 (1): 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. (2006). Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 13 (2): 121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn JS, Aulakh V, Bosworth A. (2009). What it takes: characteristics of the ideal personal health record. Health Aff (Millwood), 28 (2): 369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detmer D, Bloomrosen M, Raymond B, Tang P. (2008). Integrated personal health records: transformative tools for consumer-centric care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raisinghani MS, Young E. (2008). Personal health records: key adoption issues and implications for management. Int J Electron Healthc, 4 (1): 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (2007). HIMSS Personal Health Records: Definition and Position Statement. http://www.healthimaging.com/topics/diagnostic-imaging/himss-releases-phr-definition-position-statement.

- 22.Burrington-Brown J, Fishel J, Fox L, Friedman B, et al. (2005). Defining the personal health record. AHIMA releases definition, attributes of consumer health record. J AHIMA, 76 (6): 24–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans (2008). Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. National Academies Press, Washington (DC), US: p: 300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health (2008). NHS next stage review: our vision for primary and community care. http://www.nhshistory.net/dhvisionphc.pdf

- 25.Gu Y, Orr M, Warren J, Humphrey G, Day K, Tibby S, et al. (2013). Why a shared care record is an official medical record. N Z Med J., 126 (1384): 109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Diabetes Association (2008). Introduction. Diabetes Care, 31 (Supplement 1): S1–S2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandra LD, Deborah D. (2012). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines. 2nd ed Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing; Baltimore, Maryland, United States: p: 256. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Diabetes Federation (2016). Diabetes in Iran. https://www.idf.org/membership/mena/iran.

- 29.Farzi J, Salem safi P, Zohoor A, Ebadi Fard azar F. (2008). The study of national diabetes registry system model suggestion for Iran. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci, 8 (3): 288–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azizi A, Aboutorabi R, Mazloum-Khorasani Z, Afzal-Aghaea M, Tara M. (2016). Development, validation, and evaluation of Web-based Iranian Diabetic Personal Health Record: rationale for and protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc, 5 (1): e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azizi A, Aboutorabi R, Mazloum-Khorasani Z, Afzal-Aghaea M, Tabesh H, Tara M. (2016). Evaluating the effect of Web-based Iranian Diabetic Personal Health Record app on selfcare status and clinical indicators. JMIR Med Inform, 21 ; 4(4): e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Wersch A, de Boer MF, van der Does E, de Jong P, Knegt P, Meeuwis CA, et al. (1997). Continuity of information in cancer care: evaluation of a logbook. Patient Educ Couns, 31 (3): 223–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGinn CA, Grenier S, Duplantie J, Shaw N, Sicotte C, Mathieu L, et al. (2011). Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: a systematic review. BMC Med, 9: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalankesh LR, Dastgiri S, Rafeey M, Rasouli N, Vahedi L. (2015). Minimum data set for cystic fibrosis registry: a case study in Iran. Acta Inform Med, 23 (1): 18–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghaneie M, Rezaie A, R Ghorbani N, Heidari R, Arjomandi M, Zare M. (2013). Designing a minimum data set for breast cancer: a starting point for breast cancer registration in Iran. Iran J Public Health, 42 (1): 66–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safdari R, Dargahi H, Halabchi F, Shadanfar K, Abdolkhani R. (2014). A comparative study of the athlete health records’ minimum data set in selected countries and presenting a model for Iran. Payavard, 8(2):134–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rafii F, Ahmadi M, Hoseini AF, Habibi Koolaee M. (2011). Nursing minimum data set: an essential need for Iranian health care system. Iran J Nurs, 24 (71): 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmadi M, Mohammadi A, Chraghbaigi R, Fathi T, Shojaee Baghini M. (2014). Developing a minimum data set of the information management system for orthopedic injuries in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J, 16 (7): e17020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Health Service (NHS) Greater Glasgow and Clyde (2016). My diabetes handheld record. http://www.nhsggc.org.uk/content/mediaassets/pdf/HSD/Diabetes%20Handheld%20Record.pdf.

- 40.Kaiser foundation health plan of the mid-atlantic states (2014). Personal Diabetes Record. https://thrive.kaiserpermanente.org/care-near-mid-atlantic.

- 41.The Diabetes Coalition of California (2006). English Diabetes Health Record (DHR) card. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/cdapp/Pages/default.aspx.

- 42.National Health Service (NHS) primary care diabetes specialist team (2016). My Personal Diabetes Handheld Record and care plan. http://www.mysurgerywebsite.co.uk/website/M83041/files/Diabetes-My-Personal-Diabetes-Handheld-Record-and-Care-Plan.pdf.

- 43.NHS plymouth diabetes service (2014). Patient Held Record Diabetes. http://www.bathdiabetes.org/index2.php?section_id=550.

- 44.National Health Service (NHS) Enfield PCT Diabetes Team (2014). Patient Held Diabetes Care Record. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/upload/Shared%20practice/hand_held_record.pdf.

- 45.Kentucky Diabetes Network (2014). My Personal Diabetes Health Card. http://www.mc.uky.edu/equip-4-pcps/equip-4-dm/DIABETES_HEALTHCARD.pdf.

- 46.Lilly Diabetes (2011). This is your log book. http://www.lillydiabetes.com/_assets/pdf/hi86641_logbook.pdf.

- 47.Lilly Diabetes (2012). Personal solutions for everyday life: self-care diary. https://www.scribd.com/document/228071993/LD79617-Self-Care-Diary-10-9-12-FINAL-v1.

- 48.National Diabetes Education Program (2014). My Diabetes Care Record. http://www.pdep.org/pdfs/evryhwnshldknowbooklet.pdf.

- 49.Anonymous (2009). Checkbook for diabetes health. http://www.lillyforbetterhealth.com/_Assets/pdf/resources/HE96978-diabetes-journal-checkbook-for-diabetes-health-large-print.pdf.

- 50.The Utah State University (2014). Take charge of your health: your personal health manual. http://www.usu.edu/wellness/files/uploads/Participant_Packet.pdf.

- 51.New York Diabetes Coalition DOHD (2014). Personal Diabetes Care Card. https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/0942_en.pdf.

- 52.American Association of Diabetes Educators (2014). Measurable behavior change is the desired outcome of diabetes education. http://medicine.emory.edu/documents/endocrinology-diabetes-aade7-self-care-behaviors.pdf.

- 53.Primary Care Office Department of Health (2011). My Health Passport (for Patients with Diabetes/Hypertention). http://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/my_health_passport_patients_eng.pdf.

- 54.Wisconsin Diabetes Advisory Group and the Diabetes Prevention and Control Program (2013). Personal Diabetes Care Record. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/forms/f4/f49357.pdf.

- 55.Davies M, Quinn M. (2001). Patient-held diabetes record promotes seamless shared care. Guidelines in Practice. http://www.eguidelines.co.uk/eguidelinesmain/gip/vol_4/nov_01/davies_diabetes_nov01.htm.

- 56.Dijkstra RF, Braspenning JC, Huijsmans Z, Akkermans RP, van Ballegooie E, ten Have P, et al. (2005). Introduction of diabetes passports involving both patients and professionals to improve hospital outpatient diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 68 (2): 126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eve-Sarliker S, Bivian-Chavez M. (2014). Evaluation of Diabetes Health Record Card use among diabetes consumer action group volunteers. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/cdapp/Pages/default.aspx.

- 58.Fuji KT, Abbott AA, Galt KA. (2014). Personal Health Record design: qualitative exploration of issues inhibiting optimal use. Diabetes Care, 37 (1): e13–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wald JS, Grant RW, Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Poon EG, Businger AC, et al. (2009). Survey analysis of patient experience using a practice-linked PHR for type 2 diabetes mellitus. AMIA Annu Symp Proc, 2009:678–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grant RW, Wald JS, Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Poon EG, Orav EJ, et al. (2008). Practice-linked online personal health records for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med, 168 (16): 1776–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, Dolovich L, Bernstein B, Chan D, et al. (2009) Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. CMAJ, 181 (1–2): 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tenforde M, Nowacki A, Jain A, Hickner J. (2012). The association between personal health record use and diabetes quality measures. J Gen Intern Med, 27 (4): 420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]