Abstract

Low-dose chronic exposure to arsenic in drinking water represents a global public health concern with established risks for metabolic and cardiovascular disease, as well as cancer. While the linkage between arsenic and disease is strong, further understanding of the molecular mechanisms of its pathogenicity is required. Previous reports demonstrated the ability of arsenic to interfere with adipogenesis, which may mediate its effects in promoting metabolic disease. We hypothesized that microRNA are important regulators of most if not all mesenchymal stem cell processes that are dysregulated by arsenic exposure to impair lipogenesis. Arsenic increased the expression of miR-29b in white adipose tissue, as well as human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) isolated from adipose tissue. Exposing hMSCs to arsenic increased abundance of miR-29b and cyclin D1 to promote proliferation over differentiation. Paradoxically, inhibition of miR-29b enhanced the inhibitory effect of arsenic on differentiation. This paradox was attributed to a requirement for miR-29 in regulating cyclin D1 expression as stable inhibition of miR-29b eliminated the cyclic pattern of cyclin D1 expression. Temporal regulation of cyclin D1 is critical for adipogenic differentiation, and the data suggest a paradigm where arsenic disruption of miR-29b regulatory pathways impairs adipogenic differentiation and ultimately adipose metabolic homeostasis.

Keywords: Arsenic, microRNA, Cyclin D1, HuR, Adipogenesis, Mesenchymal stem cell

1. Introduction

Human exposure to environmental toxicants has varied negative effects on health and wellness including promotion of chronic diseases and disorders. Exposure to arsenic in drinking water contributes to several diseases including cardiovascular disease, cancer of the lung, bladder, and skin, as well as metabolic disorders, such as diabetes (Hughes et al., 2011; Maull et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2013; Patel and Kalia, 2013). While significant discoveries have been made in understanding the mechanisms of arsenic-induced cancers, mechanisms for the role of arsenic in the pathogenesis of other diseases, particularly metabolic disease, is not well understood.

microRNA (miRNA) are short non-coding RNAs that are capable of regulating cellular processes by controlling protein expression through decreasing transcript abundance or translation efficiency. miRNA are understood to regulate virtually all cell functions including proliferation, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis. After transcription in the nucleus, pri-miRNA stem loops are recognized by the Drosha processing complex, cleaved, and exported to the cytoplasm as pre-miRNA stem loops. Once in the cytoplasm the miRNAs are further cleaved by a second processing complex, the RNAse Dicer, to form the mature miRNA that targets the miRISC to the mRNAs that they recognize. The extent to which a miRNA regulates a target protein by way of mRNA-miRNA sequence complementarity can vary widely, but generally miRNAs act as modulators of protein expression rather than master regulators (Selbach et al., 2008). Of note, however, miRNAs may target several proteins within a signaling pathway such that minor effects on members of the same pathway may have a cumulative effect on cell phenotype.

Arsenic-mediated changes in miRNA expression have been linked to human disease, most prominently, cancers (Beezhold et al., 2011; Cui et al., 2012; Ngalame et al., 2014; Paul and Giri, 2015; Wang et al., 2016). However, the effect of arsenic on metabolic disorders is not well understood. Arsenic exposure regulates cell differentiation, and recently we and others reported on the inhibitory effects of arsenic on differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into adipocytes (Klei et al., 2013; Yadav et al., 2013). To further elucidate the mechanism by which arsenic might regulate adipogenesis, we determined how arsenic-induced changes in microRNA expression affects this process. Many miRNA appear to significantly impact adipogenesis, as well as the pathogenesis of diabetes. These miRNA include, miR-27, miR-31 miR-103, miR-143 and others (McGregor and Choi, 2011). All of these miRNA target various signaling processes that are critical to the differentiation of pre-adipocytes to adipose tissue (McGregor and Choi, 2011).

Arsenic exposure both in vivo and in vitro is known to regulate the expression of the cell cycle regulatory protein cyclin D1 through miRNA dependent (Sharma et al., 2013) and independent mechanisms (Li et al., 2011). Regulation of cyclin D1 by arsenic and miRNA in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation has not been shown, and is likely to have an effect as tight temporal control of cyclin D1 expression is critical to the process (Fox et al., 2008). Increasing cyclin D1 early in adipogenesis is essential for the clonal expansion phase of differentiation when mesenchymal stem cells become pre-adipocytes. As adipogenesis continues, Cyclin D1 is rapidly decreased to both reduce proliferation and increase PPARγ activity, a critical driver of adipogenic differentiation (Fu et al., 2005). Sustained increases or decreases in cyclin D1 may then have significant consequences on the adipogenic process. Multiple miRNAs have been shown to regulate cyclin D1 levels including miR-15, miR-21, miR-29, miR-302, miR-365, and miR-490 (Bonci et al., 2008; Card et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2014). One of these miRNA, miR-15a, may directly target cyclin D1 in a cancer context (Bonci et al., 2008; Deshpande et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2012), but is also known to regulate pre-adipocyte proliferation (Andersen et al., 2010). Additionally, cyclin D1 may be indirectly regulated by miR-29b through the repression of CDK2 (Xiao et al., 2013), which may play a role in diabetes (He et al., 2007).

We show here that arsenic promotes sustained cyclin D1 expression during arsenic-inhibited adipogenesis and that this may occur in part through a miRNA-mediated mechanism. We also show that alteration of miR-29b, leads to inhibition of adipogenesis indicating the importance of this small regulator and the potential impact of arsenic on homeostatic tissue maintenance or regeneration leading to pathologic disease development.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal exposure

Five to 6 week old male wild type C57BL/6NTac (Taconic Farms, Hudson NY) mice were exposed for 2 weeks to drinking water containing 0 or 100 μg/L trivalent arsenite, as previously described (Straub et al., 2008; Garciafigueroa et al., 2013). All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Fresh arsenite-containing water was provided every 2–3 days to insure that there is little As(III) oxidation to As(V). At the end of the exposure period, the mice were euthanized with CO2 and epididymal fat pads were removed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until isolation of miRNA.

2.2. Cell culture

Primary hMSCs isolated from adipose tissue were purchased from Life Line Cell Technology along with proprietary culture media for maintenance of pluripotent cells and differentiation to adipocytes. Cells were cultured and differentiated according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described (Klei et al., 2013). For exposures, arsenic solutions were prepared with sodium meta-arsenite (NaAsO2; Fisher Scientific) in culture medium.

2.3. QPCR

Total RNA from cells or frozen adipose tissue was isolated using TRIzol (ThermoFisher) following manufacturers specifications. For cell samples, 10 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed for individual miRNAs and controls using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), as specified by the manufacturer. miRNAs and controls were amplified using TaqMan MicroRNA Assays and Taqman Fast universal PCR master mix (2×) (Applied Biosystems). The following miRNAs were amplified; miR-29a-3p, miR-29b-3p, miR-29c-3p, miR-15a-5p, with either U54 or U6 as normalizing controls. For tissue, small RNA was isolated from 30 μg of total RNA using MirVana miRNA isolation kits (Qiagen). To assess the profile of arsenic induced changes, miRNA was analyzed using a RT2 miRNA Mouse, Whole Genome array (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. To assess changes in individual miRNA, 200 ng of the small RNA sample was reverse transcribed using the product RT2 miRNA First Strand Kit (Qiagen). Primer sets specific to mouse miR-27a, miR-27b, miR-29a, miR-29b and (Qiagen) were analyzed by qPCR and values obtained were normalized to housekeeping miRNA snoRNA251.

2.4. Western blotting

Total or fractionated protein isolates were obtained, as previously described (Klei et al., 2013). Protein lysates were electrophoretically separated on 4–12% precast gels (Life Technologies) and then transferred to PVDF membrane, stained with Ponceau S for protein loading and transfer quality control, rinsed, blocked with 5% Non-fat Dry milk and probed with primary antibody. Secondary antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase were diluted 1:4-5000 and membranes were incubated with ImmunStar AP Substrate (BioRad) and visualized using autoradiography film. Primary antibodies used were; anti-β actin (Sigma, A5441), anti-CHOP (Cell signaling, L63F7), anti-cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz, sc-718), anti-HuR (Santa Cruz, sc-20694), anti-perilipin (Cell Signaling, D1D8), anti-srebp1 (Santa Cruz, sc-8984).

2.5. Cell transfection and lentiviral transduction

Transient transfections of miRNA mimics and inhibitors were performed using siPORT neoFX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen). For miRNA inhibition, mIRIDIAN microRNA Inhibitors were used with miRIDIAN microRNA negative control #1 (Thermo Scientific). For forced miRNA expression, miSCRIPT miRNA mimics (Qiagen) were used with the manufacturer recommended All Stars Negative Control siRNA. Generation of stable miR-29b inhibited cells was achieved using lentiviral constructs. miR-29b targeting lentivirus was generated by cloning an inhibiting oligo sequence into the miRZip lentiviral vector backbone (System Biosciences). Lentivirus was amplified in 293 cells, isolated and used to infect cells. Stably transduced cells were selected using puromycin. The sequence cloned into the lentiviral construct was: 5′-caacactgatttcaaatggtgc-tatccggaaacactgatttcaaatggtgctaa-3.′ Cells infected with an empty GFP expressing lentivirus were used as a control.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using either one-way or two-way ANOVA where appropriate with either Tukeys or Bonferroni post-tests using GraphPad Prizm 5 software (GraphPad Software)

3. Results

3.1. In vivo arsenic exposure alters expression of adipose tissue miRNA

Low to moderate levels of arsenic in drinking water (10–250 ppb) cause remodeling of liver, vascular, and metabolic tissues in mice (Straub et al., 2008; Lemaire et al., 2011; Garciafigueroa et al., 2013; Ambrosio et al., 2014). In abdominal adipose tissue, arsenic exposure changed adipocyte phenotype and lipid storage capacity while also causing redistribution of fat to perivascular regions in skeletal muscle (Garciafigueroa et al., 2013). To examine whether the adipocyte phenotypic change was epigenetically regulated, we screened for expression changes in miRNA transcripts associated with adipogenesis and diabetes (Lin et al., 2009; McGregor and Choi, 2011; Liu et al., 2013), As seen in Table 1, arsenic exposure increased the expression of a number of miRNA by up to two fold. At the same time arsenic-exposure decreased the expression of miR-133a that normally suppresses a shift of white fat to brown fat (Liu et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Effect of arsenic on white adipose tissue miRNA expression.

| miRNA | 27a | 27b | 29a | 29b | 133a | 222 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold regulation | 1.98 | 1.52 | 1.98 | 2.14 | −1.87 | 1.16 |

| p value | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

Mice (n = 4/group) were treated with 0 or 250 μg/L As(III) in their drinking water for 2 weeks. miRNA in small RNA extracts of harvested abdominal fat were quantified by RT-PCR and data are presented as mean fold regulation compared to unexposed mice along with p values determined by two tailed Student’s t-test.

3.2. Arsenic induces miR-29 in cultured mesenchymal stem cells and differentiated adipocytes

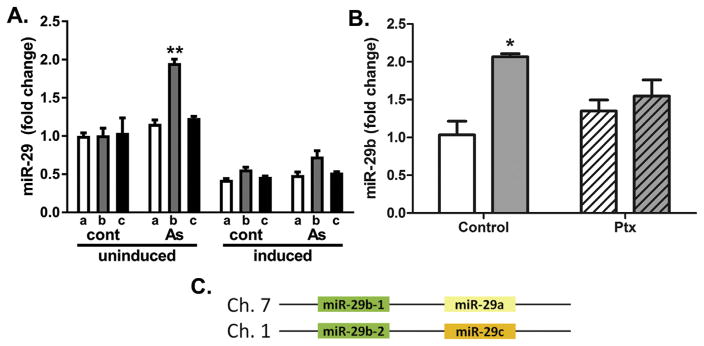

Since the miR-29 family members demonstrated the greatest change in response to arsenic in adipose tissue, their functional impact on adipogenesis and adipocyte homeostasis was examined in cultured adipose hMSC and their derivative white fat adipocytes. We previously used these models to demonstrate that non-cytotoxic exposure to arsenic (0.1–1.0 μM) caused dose-dependent and G-protein-coupled receptor mediated impairment of adipose differentiation (Klei et al., 2013) and lipid storage (Garciafigueroa et al., 2013). As seen in vivo, exposure of hMSC to 1 μM arsenic induces miR-29b expression (Fig. 1A). However, induction of miR-29a and 29c were absent in these cells. While there was a trend for arsenic to also increase miR-29b expression in cells that were differentiated into adipocytes, this did not reach significance and miR-29b expression was decreased during differentiation relative to unexposed, undifferentiated hMSC (Fig. 1A). We previously reported that arsenic-inhibited adipogenesis was mediated through G-protein coupled receptor-mediated signaling (Klei et al., 2013). Similarly, pretreating the hMSC with pertussis toxin (Ptx) to block Gαi receptor-coupled signaling prior to adding arsenic inhibited arsenic-induced miR-29b expression (Fig. 1B), suggesting that this induction is an epigenetic component of arsenic suppressed adipogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Arsenic effects on miR-29 expression. (A) RT-PCR measurement of the three miR-29 family members (a, b, c) in control and As(III)-exposed (1.0 μM) undifferentiated hMSC (24 h) and hMSC induced to differentiate into adipocytes (12 d post-induction +/− As(III). (B) hMSC were pre-treated with pertussis toxin (Ptx) for 4 h prior to 48 h incubation in the absence (white bars) or presence (grey bars) of 1 μM As(III), Data are presented as the means + s.e.m. mir-29 expression in 3 to 4 cultures. * and ** designate significance of p <0.05 or 0.01 respectively, as determined by two-way ANOVA and Bonferoni’s post-hoc tests. (C) Schematic representing the genomic organization of the miR-29 family.

3.3. Effects of arsenic miR-29b processing increase expression

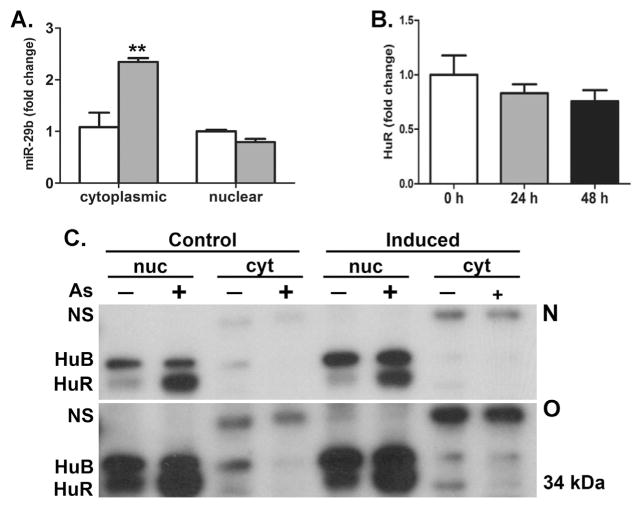

As depicted in Fig. 1C, the miR-29 family are coded by DNA sequences found on chromosomes 1 and 7 in the mouse with two copies of 29b and one each for 29a and 29c. Thus, it was surprising that arsenic had no effect on levels of miR-29a or 29c in either control or differentiated hMSC (Fig. 1A) given that either miR-29a and miR-29c should be transcribed concomitantly with miR-29b (Kriegel et al., 2012) (Fig. 1C). This suggested that differential post-transcriptional processing rather than transcription may account for miR-29b increases following arsenic exposure. As miR-29b is present in both the nucleus and cytosol (Hwang et al., 2007), we isolated total RNA from both cell fractions and observed that arsenic exposure enhanced abundance of only cytoplasmic miR-29b (Fig. 2A). The ‘AUUU’ region within the miR-29b sequence is responsible for its rapid degradation (Zhang et al., 2011), and human antigen R (HuR; ELAVL1) has been shown to bind directly to miR-29b (Balkhi et al., 2013). An earlier study suggested that arsenic increases HuR expression (Zhang et al., 2006) and we hypothesized that such an increase would regulate miR-29b abundance. While arsenic exposure did not change total HuR expression (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 1), arsenic robustly increased the abundance of nuclear HuR (Fig. 2C). Due to the low abundance of HuR in the cytoplasm, the Western blot was overexposed to assess cytoplasmic changes (Fig. 2C bottom panel) and cytoplasmic HuR, as well as HuB, were reduced by arsenic exposure, relative to a non-specific antibody-bound protein. Additionally, there appeared to be an increase in cytoplasmic HuR in cells induced in the absence of arsenic, consistent with earlier findings that HuR translocates to the cytoplasm during differentiation (Gantt et al., 2005). This suggested that nuclear sequestration of HuR may be responsible for decreasing the turnover of miR-29b, thereby enhancing its cytosolic abundance.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of HuR by arsenic may alter miR-29b levels. (A) RT-PCR measure of mir-29b in hMSC cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments with arsenic exposure (grey bars). (B) Western analysis of hMSC total cellular HuR expression following arsenic exposure. Data are fold change in mean density (± s.e.m., n = 3) of HuR protein staining normalized to total protein Ponceau staining. (C) Western analysis with normal exposure (N, upper panel) or overexposure (O, lower panel) of HuR protein expression in the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of hMSC exposed to arsenic or adipocytes differentiated in the presence or absence of arsenic. The HuR antibody also recognizes higher molecular weight HuB and a higher non- ELAVL-like cytoplasmic protein (NS). The images are representative of results from three separate experiments.

3.4. Altering miR-29b expression affects adipogenesis

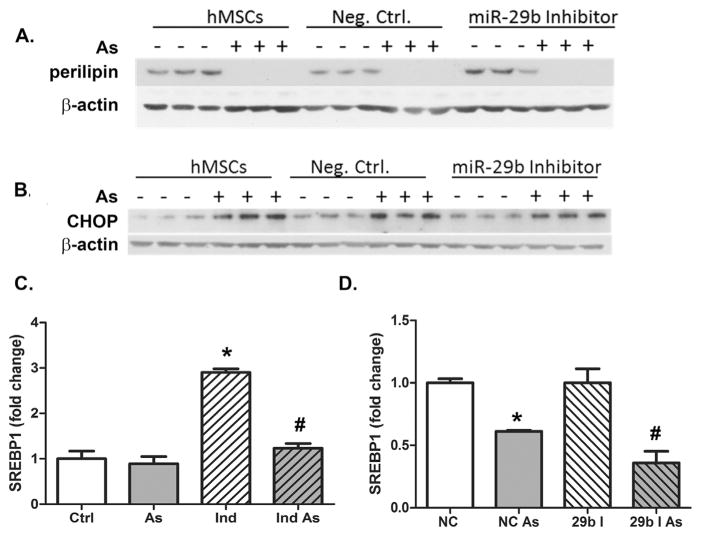

There are a number of miR-29b targets that could account for downstream effects of arsenic on adipogenesis. To identify which might be responsible for functional impact of arsenic-induced miR-29b expression on adipogenesis, we transfected cells with miR-29 inhibitory oligonuclotides and measured arsenic effects on these key targets. First, we demonstrated that inhibiting miR-29b did not affect the ability of arsenic to prevent differentiation of the hMSC into adipocytes, as indicated by the lack of expression of perilipin-1 (Fig. 3A), a key lipid droplet coat protein that is an adipocyte marker (Sztalryd and Kimmel, 2014). Adipogenesis requires a cascade of transcriptional activation initiated by C/EBPβ. CHOP (C/EBPζ) is a dominant negative inhibitor of C/EBPβ (Kim et al., 2008a; Weng et al., 2014) and an indirect target of miR-29b (Huang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008) that previous studies suggested is induced by arsenic. We confirmed that arsenic increased CHOP abundance; however, inhibiting miR-29b had no effect on basal or arsenic-stimulated CHOP expression (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of miR-29b does not reverse arsenic effects on downstream markers and regulators of adipogenesis. Western blot analysis of (A) perilipin and (B) CHOP protein expression in hMSCs induced for differentiation that are mock transfected or transfected with a negative control or miR-29b inhibiting oligonucleotide. (C) Histogram of western blot analysis of SREBP1 protein expression as a readout of differentiation 4–6 days post induction with and without arsenite exposure and quantification presented as the mean (±s.e.m.) of n = 3 cultures normalized to β-actin. * = statistical significance in the induced group compared to hMSCs alone and # = statistical significance in the induced arsenic group compared to induced alone. (D) Histogram of western blot analysis of SREBP1 expression in hMSCs induced for adipogenesis after transfection with a miR-29b inhibitor or negative control RNA quantified and presented as the mean (±s.e.m.) of n = 3 cultures normalized to β-actin. * = statistical significance compared to the negative control alone. # = statistical significance compared to miR-29b inhibitor group. Statistically significant values indicate where p <0.05.

Sterol Regulatory-Element Binding Protein 1 (SREBP1) is a transcription factor involved in adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity that is suppressed when miR-29 is overexpressed (He et al., 2007). As with perilipin-1, SREBP1 was highly induced by differentiation and arsenic prevented this increased expression (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Fig. 2A). Paradoxically, this inhibition was enhanced in hMSCs that were transiently transfected with miR-29b inhibiting oligonucleotides and exposed to arsenic in the differentiation protocol (Fig. 3D, Supplementary 2B). These data suggested that these miR-29 targets are affected by arsenic through other pathways or merely reflect the consequence of arsenic inhibition of differentiation.

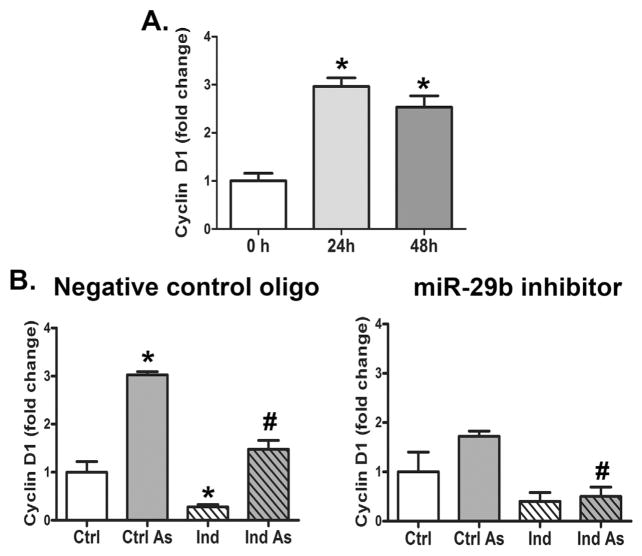

Stimulating stem cell proliferation is an indirect mechanism for preventing differentiation. Non-cytotoxic levels of arsenic are known to promote proliferation of many cell types and cyclin D1 is a critical regulator of proliferation and adipogenesis (Fox et al., 2008) that has been shown to be a miR-29 target (Wu et al., 2013). Arsenic significantly induced the expression of cyclin D1 in undifferentiated hMSCs (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Normally, when hMSCs are induced to differentiate, cyclin D1 levels rapidly rise and then greatly decrease, as see in the left panel of Fig. 4B (Supplementary Fig. 3B). With arsenic exposure, however, the cyclin D1 increased and the expression was sustained throughout 12 days of the differentiation protocol (Fig. 4B left panel, Supplementary Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

Arsenic and miR-29b Regulate cyclin D1 in differentiating hMSCs. (A) Histogram of Western analysis of cyclin D1 expression in hMSCs after exposure to 1 μM As(III) for 0, 24, or 48 h quantified and presented as the mean (± s.e.m.) of n = 3 samples normalized to Ponceau’s total protein stain. * = statistical significance compared to the unexposed hMSCs. (B) Histogram of Western analysis of cyclin D1 expression in control and induced hMSC after transfection of a miR-29b (right panel) inhibitor or negative control (left panel) with and without As(III). Quantification represents the mean (± s.e.m.) of n = 3 samples normalized to β-actin. * = statistical significance compared to the control group. # = statistical significance compared to the As(III) only group.

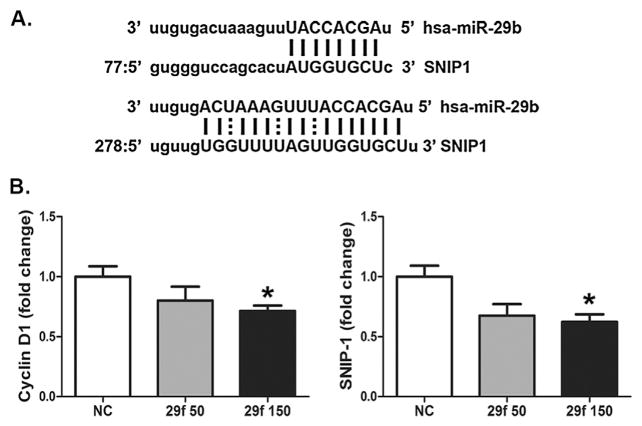

Transient transfection of the hMSC with inhibitory miR-29b oligonucleotides attenuated the arsenic-stimulated increase of cyclin D1, and allowed the full decrease in cyclin D1 during induction (Fig. 4B, right panel; Supplementary 3B). This may indicate that knockdown of miR-29b releases a brake on cyclin D1 expression keeping the cells in a more proliferative state and inhibiting adipogenesis. One candidate for this brake is Smad Nuclear Interacting Protein 1 (SNIP-1). SNIP-1 is a miR-29 target that supports expression of cyclin D1 at the level of mRNA stability (Bracken et al., 2008). There are two conserved miR-29 binding sites with good complementarity at the more distal site that predicted to be a potential target using the microRNA.org resource (Betel et al., 2008) (Fig. 5A). Simultaneous transfection of all three miR-29 family members repressed SNIP-1 and cyclin D1 suggesting that miR-29 can modulate cyclin D1 through SNIP-1 (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

miR-29b regulates RNA stabilizing protein SNIP-1. (A) A schematic depiction of miR-29b targeting the SNIP-1 3′UTR in two positions generated by MicroRNA.org. (B) Histogram of western analysis for SNIP-1 and cyclin D1 expression after forced expression of all 3 miR-29 family members at 50 and 150 nM where quantification represents the mean (±S.E.M.) of n = 3 samples normalized to β-actin. * = statistical significance compared the arsenic free control group where P <0.05.

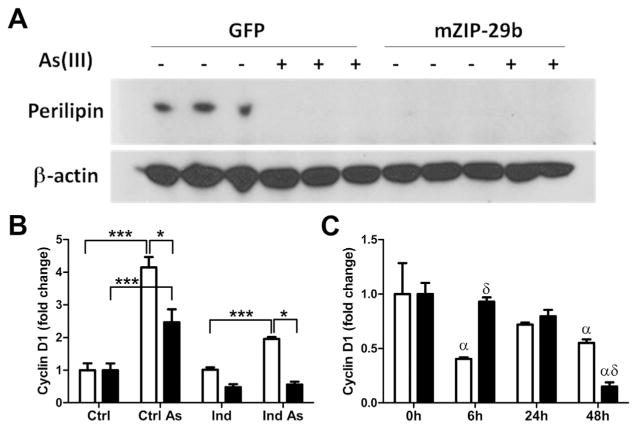

As a final control for the effectiveness of transiently transfecting the inhibitory oligomers, we used a lentiviral vector to generate hMSCs stably expressing a miR-29b inhibitor (mZIP-29b) or a GFP control construct (GFP). We assessed the cell fate of the control and mZIP-29b cells after 12 days of induction using perilipin-1 as a marker of differentiation. Similar to results from the transiently transfected cells, not only was miR-29b inhibition unable to prevent the effect of arsenic on perilipin, it actually inhibited perilipin expression suggesting that reducing miR-29b activity also inhibits normal adipogenesis (Fig. 6A). Compared to GFP expressing control cells, inhibition of miR-29b attenuated the effect of arsenic on cyclin D1 expression at day 4 post induction (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Fig. 5A), in the same manner as transient transfection in Fig. 4. Early cycling of cyclin D1 is critical for the clonal expansion phase of normal adipocyte differentiation (Fox et al., 2008). This was observed in normal hMSC that displayed an early decrease in cyclin D1 at 6 h after initiating differentiation followed by an increase that spiked at 24 h and then a decrease at 48hours. In contrast, the decrease in cyclin D1 at 6 h was lost in the mZIP-29b cells (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Fig. 5B) that fail to differentiate. This indicates that changes in miR-29b at any time point during adipogenesis can potentially inhibit the process.

Fig. 6.

Stable inhibition of miR-29b inhibits adipogenesis. (A) Western analysis for perilipin expression in control and hMSCs with stably inhibited miR-29b (mZIP-29b). (B) Histogram of Western analysis for cyclin D1 protein expression in un-induced and induced control (open bars) and mZip-29b (black bars) cells with and without arsenic. (C) Histogram of Western analysis for cyclin D1 expression during an early time course of differentiation in control (open bars) and mZip-29b (black bars) cells. The data are presented as mean ± s.e.m density of protein bands normalized to β-actin from 3 separate experiments. Significant differences in B are * p <0.05 and *** p <0.001. In C, α designates difference from time 0 for either control of mZip-29b and δ designates difference between control and mZip-29b cells at a given time point.

4. Discussion

Adipogenic differentiation of MSC, as well as arsenic inhibition of this differentiation, are complex and tightly regulated processes. The novel findings presented here suggest that miRNA are important to the regulation of the normal differentiation process and to arsenic disruption of the cyclical cell changes required for conversion of the proliferative MSC phenotype into differentiating adipocytes. The data presented suggest that arsenic impacts differentiation by disrupting the tightly regulated process of clonal expansion and proliferation in the differentiation process to stall the cells in a proliferative phase rather than allowing transition to the mature adipocyte containing perilipin-1 coated lipid droplets. These observations pose important mechanistic questions about the normal physiological roles of maintaining miR-29b levels and the impact of sustaining or over-expressing this important microRNA in pathogenic regulation of metabolic tissue remodeling.

Changes in expression of cyclin D1 after arsenic exposure have been reported and are typically described as mediating, in part, the carcinogenic effects of chronic arsenic exposure (Rossman et al., 2001; Ouyang et al., 2005; Hwang et al., 2006). To our knowledge, a role for increased cyclin D1 abundance downstream of arsenic exposure has not been described in hMSCs or as a mechanism for inhibiting stem cell differentiation in normal tissue. Whether or not increasing cyclin D1 in response to arsenic is directly culpable for inhibiting differentiation is not fully explored here. However, the increase in cyclin D1 in resting hMSCs prior to induction of differentiation at the very least creates a context where cells are more likely to divide than differentiate. Additionally, others found that reintroducing cyclin D1 into cyclin D1 null mouse embryo fibroblasts decreased baseline adipocyte differentiation through binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Fu et al., 2005).

The regulation of miRNA as mediators of the arsenic effect is complex. We find here that the changes in miRNA expression are stimulated by arsenic in resting hMSCs. However, increased expression of miR-29b following arsenic modulates but does not mediate arsenic inhibition of differentiation. Since inhibition of miR-29b alone inhibits differentiation (Fig. 6), it was not possible to demonstrate that increases in miR-29b levels is a main mechanism mediating the arsenic effect on differentiation. It is also possible that the failure to prevent arsenic effects on miR-29a targets other than cyclin D1, was the result of the strong inhibitory signal on the differentiation process produced by the absence of miR-29a and enhanced in the presence of arsenic. The fact arsenic failed to increase or sustain cyclin D1 levels in the absence of miR-29a suggests that this is a major site where increasing the miR would enhance a proliferative over a differentiation response, especially with disruption of the tight temporal control of cyclin D1 expression. While not fully confirmed, our findings suggest an additional mechanism for regulation of cyclin D1 by miR-29 through modulation of SNIP-1 expression. Caution must be taken, however, when further analyzing the effect of miR-29 on SNIP-1 due to a lack of conservation of the miR-29 binding sites in its 3′UTR between humans and mice.

The effect of arsenic on the regulation of gene expression through posttranslational mechanisms has been long studied. Of particular interest is the regulation of miRNA and RNA binding proteins that may positively or negatively regulate transcript stability through subcellular localization. An example would be recruitment or inhibition of protein complexes such as the miRNA/mRNA induced silencing complex (RISC). The miR-29 family consists of three members, of which mir-29b is duplicated. miR-29a and miR-29b-1 are transcribed from chromosome 7 and miR-29b-2 and miR-29c are transcribed from chromosome 1. All family members are extragenic, originating from a single transcript from each chromosome (Chang et al., 2008; Mott et al., 2010). In the present study, we observed increased levels of only miR-29b, suggesting a non-transcriptional mechanism of regulation. Previous reports show that arsenic exposure in vitro can increase the expression of HuR (Zhang et al., 2006). HuR regulates the activity of the RISC, as well directly binds to miR-29b (Balkhi et al., 2013). The interaction with miR-29b may be localized to an AUUU sequence as HuR has multiple ARE-binding domains. Additionally, this sequence has been shown to cause the rapid degradation of miR-29b (Zhang et al., 2011). This makes HuR an interesting candidate for mediating the regulation of miR-29b by arsenic. The current study shows arsenic does not affect total HuR expression, but does enhances its nuclear abundance and decreases the amount of HuR in the cytoplasm. Sequestrating HuR in the nucleus would block the ability of HuR to bind and degrade miR-29b in the cytoplasm. The finding of cytoplasmic levels of miR-29b increase while nuclear levels possibly decrease further supports the hypothesis that nuclear sequestration and cytoplasmic reduction of HuR stabilizes miR-29b, increasing its abundance in response to arsenic treatment.

HuR also stabilizes the cyclin D1 promoter and enhances its translation (Che et al., 2014). While not investigated in the current study, HuR is a known regulator of many mRNAs and cell processes dependent on its phosphorylation status and protein binding partners (Chen et al., 2002; Gantt et al., 2005). There are several potential avenues by which arsenic might regulate HuR. The most likely mechanism would be mediated by arsenic activation of cyclin dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) (McNeely et al., 2008). Active CDK1 phosphorylates HuR on serine 202, enhancing its association with 14-3-3 to promoting its nuclear localization (Kim et al., 2008b).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, chronic exposure to arsenic through drinking water at even low levels is recognized as hazardous and capable of contributing to the pathology of multiple diseases. In addition to our previous work (Garciafigueroa et al., 2013; Klei et al., 2013), the current studies further elucidate the mechanism(s) behind the inhibition of adipogenesis and normal adipose tissue function by arsenic exposure. These studies highlight the complex nature of miRNA molecules as not necessarily mediators of the overall effect of a stimulus, but as potential modulators to fine-tune a stem cell survival response that preserves pluripotency at the expense of tissue regeneration. Additionally, the regulation of miR-29b and HuR by arsenic opens the door for new understanding of pathophysiologic effects of arsenic, as both the miRNA and protein are integrators of a number of important regulatory pathways. The example here is the functional impact on regulating of cyclin D1 in mesenchymal stem cells by arsenic that leads to effects on homeostatic tissue maintenance or regeneration in response to an environmental stressor.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Arsenic promotes metabolic disease through poorly understood mechanisms involving pathogenic remodeling of metabolic tissue.

Low level arsenic exposure induced expression of miR-29b to impair human mesenchymal stem cell adipogenic differentiation.

miR-29a disrupted adipogenesis involved sustained cyclin D expression that prevented cell cycle exit for differentiation.

The work elucidated a novel mechanism for disruption of adipose metabolic homeostasis following arsenic exposure.ollowing arsenic exposure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant F32ES022134 (KB), as well as NIEHS Grants R01ES023696 (AB), R01ES024233 (AB), and R01ES013781 (AB).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.12.002.

Footnotes

Disclosure statements

Dr. Barchowsky and Dr. Beezhold report grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences during the conduct of the study.

References

- Ambrosio F, Brown E, Stolz D, Ferrari R, Goodpaster B, Deasy B, Distefano G, Roperti A, Cheikhi A, Garciafigueroa Y, Barchowsky A. Arsenic induces sustained impairment of skeletal muscle and muscle progenitor cell ultrastructure and bioenergetics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;74:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen DC, Jensen CH, Schneider M, Nossent AY, Eskildsen T, Hansen JL, Teisner B, Sheikh SP. MicroRNA-15a fine-tunes the level of Delta-like 1 homolog (DLK1) in proliferating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1681–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkhi MY, Iwenofu OH, Bakkar N, Ladner KJ, Chandler DS, Houghton PJ, London CA, Kraybill W, Perrotti D, Croce CM, Keller C, Guttridge DC. miR-29 acts as a decoy in sarcomas to protect the tumor suppressor A20 mRNA from degradation by HuR. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beezhold K, Liu J, Kan H, Meighan T, Castranova V, Shi X, Chen F. miR-190-mediated downregulation of PHLPP contributes to arsenic-induced Akt activation and carcinogenesis. Toxicol Sci. 2011;123:411–420. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonci D, Coppola V, Musumeci M, Addario A, Giuffrida R, Memeo L, D’Urso L, Pagliuca A, Biffoni M, Labbaye C, Bartucci M, Muto G, Peschle C, De Maria R. The miR-15a-miR-16-1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nat Med. 2008;14:1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/nm.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken CP, Wall SJ, Barre B, Panov KI, Ajuh PM, Perkins ND. Regulation of cyclin D1 RNA stability by SNIP1. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7621–7628. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CK, Zhao GY, Tian LY, Liu L, Yan K, Ma YL, Ji ZW, Li XX, Han K, Gao J, Qiu XC, Fan QY, Yang TT, Ma BA. miR-15a and miR-16-1 downregulate CCND1 and induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1764–1770. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card DA, Hebbar PB, Li L, Trotter KW, Komatsu Y, Mishina Y, Archer TK. Oct4/Sox2-regulated miR-302 targets cyclin D1 in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6426–6438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, Dang CV, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Mendell JT. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Y, Yi L, Akhtar J, Bing C, Ruiyu Z, Qiang W, Rong W. AngiotensinII induces HuR shuttling by post-transcriptional regulated CyclinD1 in human mesangial cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:1141–1150. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu AB. Highly selective actions of HuR in antagonizing AU-rich element-mediated mRNA destabilization. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7268–7278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7268-7278.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Han Z, Hu Y, Song G, Hao C, Xia H, Ma X. MicroRNA-181b and microRNA-9 mediate arsenic-induced angiogenesis via NRP1. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:772–783. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Pastore A, Deshpande AJ, Zimmermann Y, Hutter G, Weinkauf M, Buske C, Hiddemann W, Dreyling M. 3′UTR mediated regulation of the cyclin D1 proto-oncogene. ABBV Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3592–3600. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KE, Colton LA, Erickson PF, Friedman JE, Cha HC, Keller P, MacDougald OA, Klemm DJ. Regulation of cyclin D1 and Wnt10b gene expression by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein during early adipogenesis involves differential promoter methylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35096–35105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806423200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Rao M, Bouras T, Wang C, Wu K, Zhang X, Li Z, Yao TP, Pestell RG. Cyclin D1 inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-mediated adipogenesis through histone deacetylase recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16934–16941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt K, Cherry J, Tenney R, Karschner V, Pekala PH. An early event in adipogenesis, the nuclear selection of the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein {beta} (C/EBP{beta}) mRNA by HuR and its translocation to the cytosol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24768–24774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garciafigueroa DY, Klei LR, Ambrosio F, Barchowsky A. Arsenic-stimulated lipolysis and adipose remodeling is mediated by g-protein-coupled receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2013;134:335–344. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Yang T, Fu S, Chen X, Guo L, Ni Y. MicroRNA-490-3p inhibits proliferation of A549 lung cancer cells by targeting CCND1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;444:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SL, Ye H, Teng Y, Wang YL, Yang G, Li XB, Zhang C, Yang X, Yang ZZ. Akt-p53-miR-365-cyclin D1/cdc25A axis contributes to gastric tumorigenesis induced by PTEN deficiency. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2544. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A, Zhu L, Gupta N, Chang Y, Fang F. Overexpression of micro ribonucleic acid 29, highly up-regulated in diabetic rats, leads to insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2785–2794. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HY, Li X, Liu M, Song TJ, He Q, Ma CG, Tang QQ. Transcription factor YY1 promotes adipogenesis via inhibiting CHOP-10 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MF, Beck BD, Chen Y, Lewis AS, Thomas DJ. Arsenic exposure and toxicology: a historical perspective. Toxicol Sci. 2011;123:305–332. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang BJ, Utti C, Steinberg M. Induction of cyclin D1 by submicromolar concentrations of arsenite in human epidermal keratinocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;217:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HW, Wentzel EA, Mendell JT. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science. 2007;315:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1136235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EH, Yoon MJ, Kim SU, Kwon TK, Sohn S, Choi KS. Arsenic trioxide sensitizes human glioma cells, but not normal astrocytes, to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein-dependent DR5 up-regulation. Cancer Res. 2008a;68:266–275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Pullmann R, Jr, Yang X, Galban S, Srikantan S, Martindale JL, Blethrow J, Shokat KM, Gorospe M. Nuclear HuR accumulation through phosphorylation by Cdk1. Genes Dev. 2008b;22:1804–1815. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klei LR, Garciafigueroa DY, Barchowsky A. Arsenic activates endothelin-1 Gi protein-coupled receptor signaling to inhibit stem cell differentiation in adipogenesis. Toxicol Sci. 2013;131:512–520. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegel AJ, Liu Y, Fang Y, Ding X, Liang M. The miR-29 family: genomics, cell biology, and relevance to renal and cardiovascular injury. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:237–244. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00141.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire M, Lemarie CA, Molina MF, Schiffrin EL, Lehoux S, Mann KK. Exposure to moderate arsenic concentrations increases atherosclerosis in apoE (−/−) mouse model. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122:211–221. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Shen L, Xu H, Pang Y, Xu Y, Ling M, Zhou J, Wang X, Liu Q. Up-regulation of cyclin D1 by JNK1/c-Jun is involved in tumorigenesis of human embryo lung fibroblast cells induced by a low concentration of arsenite. Toxicol Lett. 2011;206:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Gao Z, Alarcon RM, Ye J, Yun Z. A role of miR-27 in the regulation of adipogenesis. FEBS J. 2009;276:2348–2358. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Bi P, Shan T, Yang X, Yin H, Wang YX, Liu N, Rudnicki MA, Kuang S. miR-133a regulates adipocyte browning in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maull EA, Ahsan H, Edwards J, Longnecker MP, Navas-Acien A, Pi J, Silbergeld EK, Styblo M, Tseng CH, Thayer KA, Loomis D. Evaluation of the association between arsenic and diabetes: a national toxicology program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:1658–1670. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor RA, Choi MS. microRNAs in the regulation of adipogenesis and obesity. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:304–316. doi: 10.2174/156652411795677990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely SC, Taylor BF, States JC. Mitotic arrest-associated apoptosis induced by sodium arsenite in A375 melanoma cells is BUBR1-dependent. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;231:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon KA, Guallar E, Umans JG, Devereux RB, Best LG, Francesconi KA, Goessler W, Pollak J, Silbergeld EK, Howard BV, Navas-Acien A. Association between exposure to low to moderate arsenic levels and incident cardiovascular disease. Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:649–659. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JL, Kurita S, Cazanave SC, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Transcriptional suppression of mir-29b-1/mir-29a promoter by c-Myc, hedgehog, and NF-kappaB. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:1155–1164. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngalame NN, Tokar EJ, Person RJ, Xu Y, Waalkes MP. Aberrant microRNA expression likely controls RAS oncogene activation during malignant transformation of human prostate epithelial and stem cells by arsenic. Toxicol Sci. 2014;138:268–277. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W, Ma Q, Li J, Zhang D, Liu ZG, Rustgi AK, Huang C. Cyclin D1 induction through IkappaB kinase beta/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway is responsible for arsenite-induced increased cell cycle G1-S phase transition in human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9287–9293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel HV, Kalia K. Role of hepatic and pancreatic oxidative stress in arsenic induced diabetic condition in Wistar rats. J Environ Biol/Acad Environ Biol India. 2013;34:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Giri AK. Epimutagenesis: a prospective mechanism to remediate arsenic-induced toxicity. Environ Int. 2015;81:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman TG, Uddin AN, Burns FJ, Bosland MC. Arsenite is a cocarcinogen with solar ultraviolet radiation for mouse skin: an animal model for arsenic carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;176:64–71. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Sharma S, Arora M, Kaul D. Regulation of cellular Cyclin D1 gene by arsenic is mediated through miR-2909. Gene. 2013;522:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub AC, Clark KA, Ross MA, Chandra AG, Li S, Gao X, Pagano PJ, Stolz DB, Barchowsky A. Arsenic-stimulated liver sinusoidal capillarization in mice requires NADPH oxidase-generated superoxide. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3980–3989. doi: 10.1172/JCI35092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztalryd C, Kimmel AR. Perilipins: lipid droplet coat proteins adapted for tissue-specific energy storage and utilization, and lipid cytoprotection. Biochimie. 2014;96:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Garzon R, Sun H, Ladner KJ, Singh R, Dahlman J, Cheng A, Hall BM, Qualman SJ, Chandler DS, Croce CM, Guttridge DC. NF-kappaB-YY1-miR-29 regulatory circuitry in skeletal myogenesis and rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ge X, Zheng J, Li D, Liu X, Wang L, Jiang C, Shi Z, Qin L, Liu J, Yang H, Liu LZ, He J, Zhen L, Jiang BH. Role and mechanism of miR-222 in arsenic-transformed cells for inducing tumor growth. Oncotarget. 2016;7:17805–17814. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng CY, Chiou SY, Wang L, Kou MC, Wang YJ, Wu MJ. Arsenic trioxide induces unfolded protein response in vascular endothelial cells. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88:213–226. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Huang X, Zou Q, Guo Y. The inhibitory role of Mir-29 in growth of breast cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res: CR. 2013;32:98. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Rao JN, Zou T, Liu L, Cao S, Martindale JL, Su W, Chung HK, Gorospe M, Wang JY. miR-29b represses intestinal mucosal growth by inhibiting translation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3038–3046. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S, Anbalagan M, Shi Y, Wang F, Wang H. Arsenic inhibits the adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by down-regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and CCAAT enhancer-binding proteins. Toxicol In Vitro. 2013;27:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bhatia D, Xia H, Castranova V, Shi X, Chen F. Nucleolin links to arsenic-induced stabilization of GADD45alpha mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:485–495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zou J, Wang GK, Zhang JT, Huang S, Qin YW, Jing Q. Uracils at nucleotide position 9–11 are required for the rapid turnover of miR-29 family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4387–4395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Ren Y, Moore L, Mei M, You Y, Xu P, Wang B, Wang G, Jia Z, Pu P, Zhang W, Kang C. Downregulation of miR-21 inhibits EGFR pathway and suppresses the growth of human glioblastoma cells independent of PTEN status. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol. 2010;90:144–155. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.