Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship of both pubertal development and sex to childhood irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) clinical characteristics including gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, abdominal pain) and psychological factors.

Study design

Cross-sectional study with children ages 7–17 years (n = 143) with a pediatric Rome III IBS diagnosis recruited from both primary and tertiary clinics between January 2009 and January 2014. Subjects completed 14-day prospective pain and stool diaries, as well as validated questionnaires assessing several psychological factors (somatization, depression, anxiety) and Tanner stage. Stool form ratings were completed using the Bristol Stool Form Scale.

Results

Girls with higher Tanner scores (more mature pubertal development) had both decreased pain severity and pain interference; in contrast, boys with higher Tanner scores had both increasing pain severity (β = 0.40, P = .02) and pain interference (β = 0.16, P = .02). Girls (vs boys), irrespective of pubertal status, had both increased somatic complaints (P = .005) and a higher percentage (P = .01) of hard (Bristol Stool Form Scale type 1 or 2) stools. Pubertal status and sex did not significantly relate to IBS subtype, pain frequency, stooling frequency, anxiety, or depression.

Conclusions

In children with IBS, both pubertal development and/or sex are associated with abdominal pain severity, stool form, and somatization. These differences provide insight into the role of pubertal maturation during the transition from childhood to adult IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is highly prevalent in both children and adults throughout the world. Large school and community-based studies identify IBS-type symptoms in 8%–25% of children and up to 20% of adults.1–5 Up to 66% of children with IBS will transition to have adult IBS.6–10

Despite both its worldwide prevalence and impact, the differences in childhood IBS phenotype at various pubertal developmental stages is poorly characterized. Both IBS gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological characteristics have been evaluated in children of various ages using school- and/or community-based questionnaires without attention to developmental pubertal stage.1–3 These data may be unreliable as questionnaire-based recall differ significantly vs prospective diaries.11,12 The lack of knowledge as to whether pubertal development affects IBS clinical presentation represents a barrier to efforts aimed at halting the transition from childhood to adult IBS.

Sex may also play a role in the transition from childhood IBS to adult IBS. Children with IBS have different sex-specific physiological responses.13 Though at times conflicting, several studies have identified several sex-based differences in adult IBS gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological factors.14 Therefore, elucidating the relationship of both pubertal stage and sex in childhood IBS may provide insight into the common progression of pediatric to adult IBS.15 Given this, the objective of our study was to determine the relationship of both pubertal development and sex to childhood IBS clinical characteristics including gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, abdominal pain) and psychological factors (eg, depression).

Methods

Children ages 7–17 years included in this study were part of larger, prospective studies in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Only data prior to any intervention were used. The data were captured between January 2009 and January 2014. All recruitment and study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from the parent and assent from the child.

Participants were identified by medical chart review based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes of 789.0 (abdominal pain) or 564.1 (irritable bowel syndrome) from a large academic pediatric gastroenterology practice and general pediatrician offices within the same affiliated hospital system.

Children were excluded if chart review or phone screening identified: an organic gastrointestinal illness; a co-occurring significant chronic health condition; vomiting ≥2 times a month for the preceding 3 months; unexplained weight loss; blood in stool; current use of any medication that completely alleviated the pain; lack of fluency in English (as some of the questionnaires are only available in English); and significant developmental delay (preventing questionnaire or diary completion). Participants were included in the study if they qualified as having IBS using Pediatric Rome III criteria by phone screening using a modification of the Pediatric Rome III questionnaire.16 The modification asked about presence or absence of symptoms rather than the percentage of time the symptom occurred.

Pain and Stool Diaries

Children completed 14-day pain and stool diaries as we have described previously.17 Parents were instructed only to remind children to complete the diaries, and children were instructed to record the data without parental influence. Children rated their pain 3 times a day using a 0–10 scale anchored with the phrases “no pain at all” and “the worst pain you can imagine.” Mean pain severity was defined as each child’s average pain severity for intervals when pain was present over the course of 2 weeks. Pain frequency was defined as the number of pain episodes a child reported over the 2-week period. With each rating, degree of interference with activities because of pain was rated on a 4-point scale (0 = no interference; 1 = a little interference; 2 = a lot of interference; 3 = could not participate because of pain), and the mean of the interference ratings during pain episodes was calculated.17 Children were instructed to call in their responses to a dedicated phone line linked to a computerized database at the end of each day. Research coordinators contacted the family for any missing entries.

Stool frequency and stool form were recorded using the Bristol Stool Form Scale; constipated stools were classified as stool form types 1 or 2 and diarrheal stools were classified as types 6 or 7.18 Mean stool frequency per day and stool form percentages for constipation and diarrhea over the 14 days were calculated for each participant. IBS subtypes were determined based on stool form as per Rome III criteria.19

Children were shown sex appropriate Tanner staging drawings and asked to choose the representation that best matched their own bodies.20 The self-report staging drawings consist of 2 pictures: for girls, 1 picture depicting breast development and 1 depicting pubic hair growth; for boys, 1 picture depicting genital size and 1 depicting pubic hair growth.20 The 2 ratings were averaged for each participant.20 Tanner self-assessment ratings of pubertal status have been shown to correlate well with physical examination by physicians.21–24 In addition self-assessment ratings of pubertal status have been reported to correlate with hormonal markers of pubertal development.20

The Children’s Somatization Inventory was used to assess somatic symptoms in children.25 The child rates the degree to which each of 35 symptoms bothered him/her in the past 2 weeks on a 5-point scale (“not at all” to “a whole lot”). Total scores are calculated by summing the values for each item.

The Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition is a psychometrically robust instrument used to measure a range of behavioral and emotional problems in children.26 This study used T scores on the anxiety and depression scales from the child self-report forms.

Data Analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics v 23, 2015 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Generalized linear models were used to evaluate the degree to which both Tanner stage and sex predicted pain, stooling, somatization, and psychological factors. Tanner stage and sex main effects were included in the same step along with the interaction of the 2 variables. With each regression analysis, potential interactions between independent variables were evaluated. If a statistically significant (P < .05) interaction effect was not identified, the interaction evaluation was removed from the model, and the main effects of each independent variable were assessed. A χ2 analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between sex and IBS bowel pattern subtype. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the relationship between IBS subtypes and Tanner stage. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

A total of 143 participants were included in the study; the mean age was 12.9 ± 2.8 (SD) years. Demographic and pubertal stage classification breakdown is listed in the Table (available at www.jpeds.com). No statistically significant demographic differences were found between boys and girls. As expected, pubertal stage and age were highly but not completely correlated (r = 0.77, P < .001).

Table.

Demographics

| Girls (n = 90) | Boys (n = 53) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 55 (61.1%) | 32 (60.4%) |

| Hispanic | 19 (21.1%) | 11 (20.8%) |

| African American | 13 (14.4%) | 7 (13.2%) |

| Asian | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (3.8%) |

| More than 1 race | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Mother’s educational level | ||

| High school degree, GED, or less | 12 (13.3%) | 6 (11.3%) |

| Some college/vocational training | 27 (30.0%) | 23 (44.4%) |

| College graduate | 40 (44.4%) | 16 (18.9%) |

| Professional degree | 10 (11.1%) | 6 (11.3%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.8%) |

| Insurance status | ||

| HMO/PPO | 71 (78.8%) | 41 (77.4%) |

| Medicaid/CHIPS | 18 (20.0%) | 9 (17.0%) |

| Other | 1 (1.1%) | 3 (5.7%) |

| Tanner stage | ||

| 1 | 8 (8.8%) | 3 (5.7%) |

| 1.5 | 5 (5.5%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| 2 | 11 (12.2%) | 10 (18.9%) |

| 2.5 | 6 (6.6%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| 3 | 5 (5.5%) | 7 (13.2%) |

| 3.5 | 11 (12.2%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| 4 | 15 (16.6%) | 8 (15.1%) |

| 4.5 | 18 (20.0%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| 5 | 11 (12.2%) | 5 (9.4%) |

CHIPS, Children’s Health Insurance Program; GED, general education development; HMO, health maintenance organization; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Prediction of Abdominal Pain Characteristics by Sex and Pubertal Status

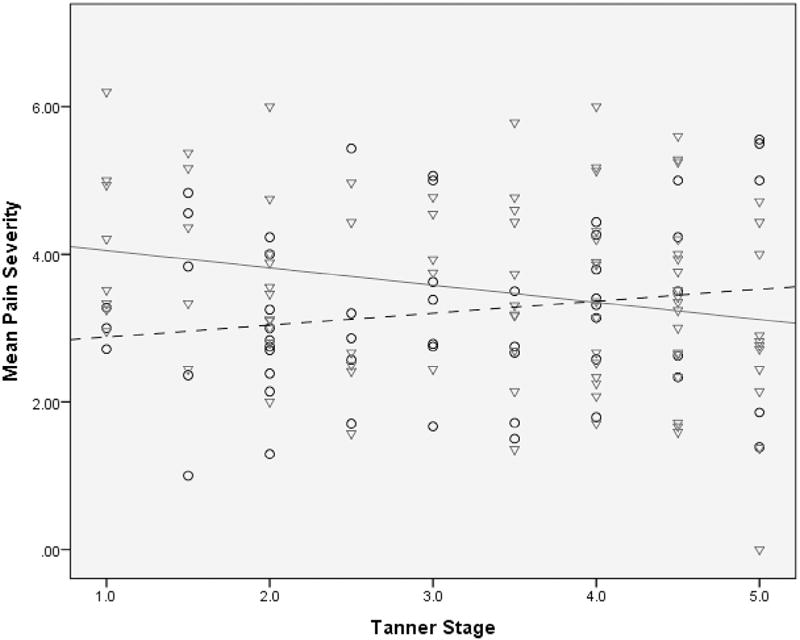

There was no difference within the studied population with respect to the sex distribution across Tanner stages (t [1,141] = −1.646, P = .15). When evaluating pain severity, a significant interaction between pubertal stage and sex emerged (β = 0.40, CI 95% 0.07–0.72, P = .02; Figure 1). Girls with higher Tanner scores (more pubertal development) had lower pain severity, and boys with higher Tanner scores had increased pain severity. There was no interaction or identified independent relationship between pain frequency and either pubertal stage or sex.

Figure 1.

This regression model shows the interaction of sex and puberty on pain severity in 143 children with IBS. Pain severity decreased in females with higher Tanner scores; in males pain severity increased with higher Tanner scores. The males (n = 53) are circles with a dashed trend line; the females (n = 90) are triangles with a solid trend line.

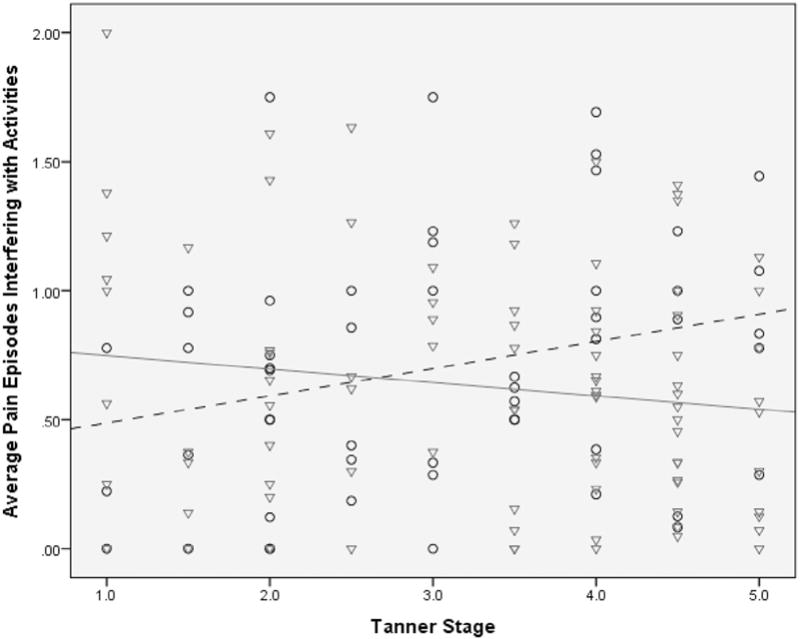

When evaluating the degree of interference with activities because of pain, there was also a similar significant interaction between pubertal stage and sex (β = 0.16, CI 95% 0.03–0.29, P = .02; Figure 2). Girls with higher Tanner scores reported less activity interference because of pain than girls with lower Tanner scores. In contrast, boys with higher Tanner scores (compared with boys with lower Tanner scores) reported increased levels of interference with daily activities.

Figure 2.

This regression model shows the interaction of sex and puberty on pain interference with activities. Pain interference with activities decreased in females with higher Tanner scores; in males, pain interference with activities increased with higher Tanner scores. The males (n = 53) are circles with a dashed trend line; the females (n = 90) are triangles with a solid trend line.

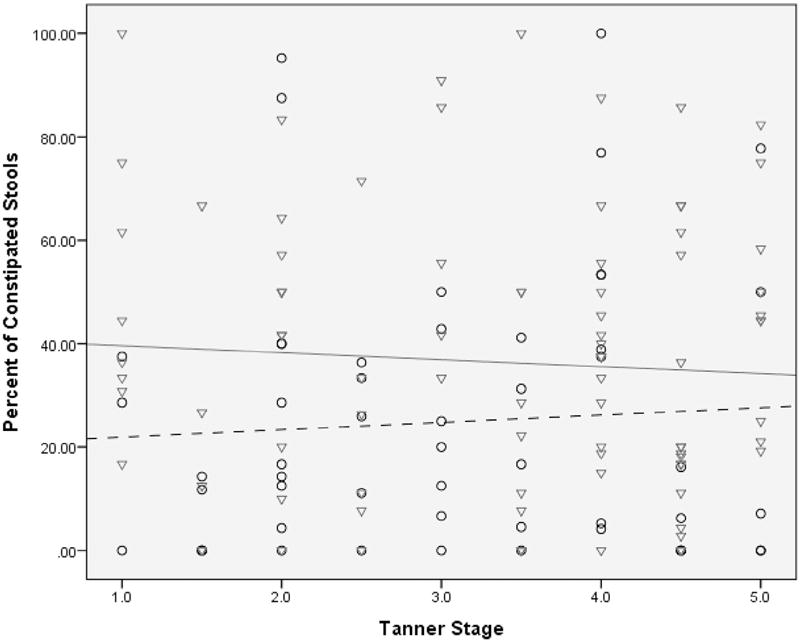

Prediction of Bowel Habits by Sex and Pubertal Stage

No statistically significant interaction between pubertal stage and sex was identified when evaluating mean stool frequency per day or mean stool type. Irrespective of pubertal stage, sex was significantly associated with the percentage of stools rated as constipated with boys having a lower percentage of stools rated as constipated compared with girls (24.8% vs 35.6%, respectively, P = .01; Figure 3). Tanner stage and sex were not significantly related to the percentage of stools rated as diarrheal or to stooling frequency.

Figure 3.

This regression model shows the relationship of sex and puberty on percentage of constipated (type 1 and 2 stools on Bristol Stool Form Scale) children with IBS. Irrespective of pubertal maturation, males (vs females) have a lower percentage of constipated stools. The males (n = 53) are circles with a dashed trend line; the females (n = 90) are triangles with a solid trend line.

The IBS subtypes of the study population were 51.7% IBS-constipation, 39.2% IBS-unspecified, 6.3% IBS-diarrhea, and 2.8% IBS-mixed. The distribution of IBS subtypes did not significantly differ between boys and girls (χ2 [3, 143] = 4.996, P = .17). While controlling for sex, the relationship between pubertal stage and IBS subtype for boys or girls was not statistically significant ([H (3) = 0.86, P = .84], [H (3) = 1.74, P = .63], respectively).

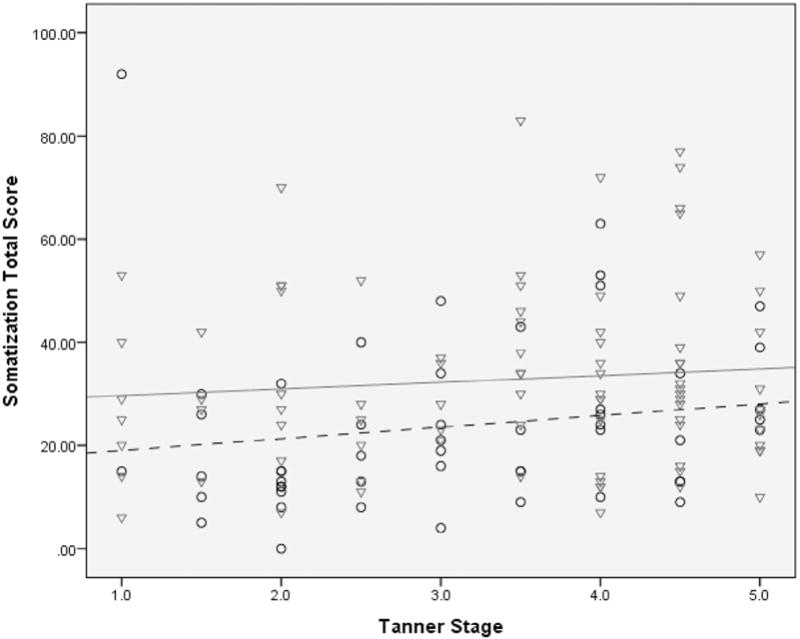

Prediction of Psychological Factors by Sex and Pubertal Stage

There were no statistically significant interactions identified between pubertal stage and sex associated with somatization, anxiety, or depression. While controlling for pubertal stage, sex was significantly related to degree of somatization with girls endorsing more somatic complaints than boys (P = .005; Figure 4). There were no statistically significant relationships between pubertal stage and sex for either depression or anxiety (data not shown).

Figure 4.

This regression model shows the relationship of sex and puberty on somatization. The degree of somatization was determined using total scores (higher scores corresponding to higher somatization). Irrespective of pubertal status, females endorsed more somatic complaints than males. The males (n = 53) are circles with a dashed trend line; the females (n = 90) are triangles with a solid trend line.

Discussion

This study evaluated IBS symptoms and associated psychological factors in a cross-sectional pediatric sample while taking into account both pubertal stage and sex. We found that sex and puberty are important with both independent and interaction effects identified. Boys were found to have greater abdominal pain severity and interference because of pain with pubertal maturation, but the opposite relationship was found in girls. Regardless of pubertal stage, girls were more likely to have both more constipated stools and more somatic symptoms. These findings suggest that both sex and pubertal status have an influence on the symptoms of pediatric IBS.

Despite the striking changes in biological, cognitive, and psychological functions adolescents undergo during puberty,27 we are unaware of previous work evaluating the role of both pubertal status and sex in symptoms and psychological factors in children with IBS. Adult studies suggest that women tend to report more IBS symptoms (eg, bloating) than men, but abdominal pain does not tend to differ between sexes.28,29 Although our current study is unable to delineate how the interaction between sex and pubertal maturation occurs, we hypothesize it may be related in part to both a combination of different sex specific IBS physiological responses (eg, autonomic nervous system function), as well as personal factors.13 Personal factors, such as pain acceptance or self-efficacy to achieve an activity, have been shown to impact both attention to pain and engagement in daily activities.30 Future studies in this area may consider evaluating both personal factors related to pain and pubertal maturation.

Pubertal maturation has been associated with a higher prevalence of chronic pain disorders, such as headaches, abdominal pain, and temporomandibular joint disorder.31 In parallel, female sex also has been associated with a higher prevalence of chronic pain states, such as headaches32 and IBS.33 Our study differs from these previous studies in that we prospectively evaluate symptom expression by sex after having IBS identified rather than evaluate presence or absence (prevalence) of a disorder alone.

We found that girls had more frequent constipation type stools compared with boys. Our findings are supported by those of Giannetti et al34 and our previous work reporting girls as more likely to have hard (type 1 or 2) stools compared with boys with IBS who had a higher prevalence of loose (type 6 or 7) stools.19 This is similar to the adult literature, which notes men reporting more diarrhea symptoms than women.14,28,29 New is our observation that pubertal status did not relate to stooling characteristics. This relationship between female sex and more constipated stools appears to continue through adulthood where women with IBS are more likely to have infrequent and harder stools compared with men with IBS.14

The differences in stooling characteristics between girls and boys did not meet thresholds to change subtype categories.19 Ovarian hormones have been found to affect gastrointestinal motor function in both healthy and IBS populations with both estrogen and progesterone having effects on colonic motility.35,36 Our findings that girls, irrespective of pubertal status, have harder stools suggests that even prepubertal related levels of these sex hormones may have an influence on colonic function, or other nonpubertal related mechanisms that remain to be elucidated may be playing a role.

Somatization is generally associated with chronic pain disorders and IBS in particular.37–40 In contrast to previous studies reporting no sex difference in somatic complaints in either healthy children or children with functional gastrointestinal disorders,37,41 we found that girls reported more somatic complaints compared with boys in our sample of children with IBS. Differences between our study and previous reports may be related to the different populations evaluated and methods used. Our population consisted of children with a pediatric Rome III diagnosis of IBS, whereas Tsao et al41 studied healthy children, and Ernst et al37 evaluated the broader entity of recurrent abdominal pain. Our findings converge with adult studies, which have identified higher amounts of somatization in women with IBS compared with men.40

Contrary to our hypothesis, the other psychological domains (anxiety and depression) were not related to pubertal stage or sex. In the general population beginning in midpuberty, there is an increased risk for depression in girls vs boys.42 One study in adults with IBS found that women scored higher than men on anxiety and depression measures.28 However, lending credence to our findings, Cain et al29 reported no differences in anxiety or depression scores (from their community recruited adults) between men and women with IBS using a daily symptom diary.

The primary limitation of our study is its cross-sectional nature, allowing for determination of associations but limiting inference of causal relationships between the factors examined. Another limitation is use of self-rated pubertal status rather than an independent assessment. However, previous literature supports that children can independently rate their Tanner stage well and that this is as accurate as estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone measurements in healthy girls.20 Finally, girls of more advanced pubertal status may have been in different stages of their menstrual cycle during data collection as studies in adult women with IBS report more IBS symptoms during different phases (correlating with different hormonal levels) of the menstrual cycle.14,43,44 Future studies in girls with IBS may consider documenting symptoms during various stages of the menstrual cycle.

We used in-depth, validated questionnaires and prospective daily pain and stooling diaries; diary capture of symptoms has been demonstrated to be more accurate than recall.45 Previous studies evaluating adolescents with IBS have been retrospective and questionnaire based, which may be associated with inconsistent results. A second strength is the evaluation of pubertal stage rather than age alone as a means to assess maturation. A final strength is that participants were recruited from a large pediatric health care network, including both primary care and tertiary care settings, increasing the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, in children with IBS, both pubertal development and/or sex are associated with abdominal pain severity, stool form, and somatization. These differences provide insight into the transition of childhood to adult IBS and may better inform future research efforts to prevent this transition from occurring.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NR05337 [to R.S.], R01 NR013497 [to R.S.], and K23 DK101688 [to B.C.]), the Daffy’s Foundation, the US Dairy Association (USDA)/Agricultural Research Service (6250-51000-043 and P30-DK56338 [to the Texas Medical Center Digestive Disease Center]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the USDA; mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Devanarayana NM, Mettananda S, Liyanarachchi C, Nanayakkara N, Mendis N, Perera N, et al. Abdominal pain-predominant functional gastrointestinal diseases in children and adolescents: prevalence, symptomatology, and association with emotional stress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:659–65. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182296033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong L, Dingguo L, Xiaoxing X, Hanming L. An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and children in China: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e393–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, Rzepski B, Andrulonis PA. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129:220–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–21, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apley J, Hale B. Children with recurrent abdominal pain: how do they grow up? Br Med J. 1973;3:7–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5870.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bury RG. A study of 111 children with recurrent abdominal pain. Aust Paediatr J. 1987;23:117–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1987.tb02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen MF, Mortensen O. Long-term prognosis in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Arch Dis Child. 1975;50:110–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.50.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magni G, Pierri M, Donzelli F. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: a long term follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 1987;146:72–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00647291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker LS, Guite JW, Duke M, Barnard JA, Greene JW. Recurrent abdominal pain: a potential precursor of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr. 1998;132:1010–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czyzewski DI, Lane MM, Weidler EM, Williams AE, Swank PR, Shulman RJ. The interpretation of Rome III criteria and method of assessment affect the irritable bowel syndrome classification of children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:403–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Self MM, Williams AE, Czyzewski DI, Weidler EM, Shulman RJ. Agreement between prospective diary data and retrospective questionnaire report of abdominal pain and stooling symptoms in children with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1110–9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Czyzewski D, Zeltzer L, Shulman RJ. Autonomic nervous system function in young children with functional abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome. J Pain. 2012;13:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adeyemo MA, Spiegel BM, Chang L. Meta-analysis: do irritable bowel syndrome symptoms vary between men and women? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:738–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. quiz 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulman RJ, Eakin MN, Jarrett M, Czyzewski DI, Zeltzer LK. Characteristics of pain and stooling in children with recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:203–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000243437.39710.c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Self MM, Czyzewski DI, Chumpitazi BP, Weidler EM, Shulman RJ. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome in children and adolescents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapkin AJ, Tsao JC, Turk N, Anderson M, Zeltzer LK. Relationships among self-rated tanner staging, hormones, and psychosocial factors in healthy female adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Nottelmann ED, Inoff-Germain ED, Ghrousos GP. Perceptions of puberty: adolescent, parent, and health care personnel. Dev Psychol. 1990;26:322–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankowski B, Duke-Duncan P, Guillot A, McDougal D, Wasserman R, Young P. Young adolescents’ self-assessment of sexual maturation. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:385–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris NM, Udry JR. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. J Youth Adolesc. 1980;9:271–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02088471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlossberger NM, Turner RA, Irwin CE., Jr Validity of self-report of pubertal maturation in early adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:109–13. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90075-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garber J, Walker LS, Zeman J. Somatization symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents: further validation of the Children’s Somatization Inventory. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:588–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children. Circle Pines (MN): American Guidance Service, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blakemore SJ, Burnett S, Dahl RE. The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:926–33. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjorkman I, Jakobsson Ung E, Ringstrom G, Tornblom H, Simren M. More similarities than differences between men and women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:796–804. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Rosen S, Hertig VL, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in gastrointestinal, psychological, and somatic symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1542–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viane I, Crombez G, Eccleston C, Devulder J, De Corte W. Acceptance of the unpleasant reality of chronic pain: effects upon attention to pain and engagement with daily activities. Pain. 2004;112:282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeResche L, Mancl LA, Drangsholt MT, Saunders K, Von Korff M. Relationship of pain and symptoms to pubertal development in adolescents. Pain. 2005;118:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wober-Bingol C. Epidemiology of migraine and headache in children and adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:341. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0341-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korterink JJ, Diederen K, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Epidemiology of pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannetti E, de’Angelis G, Turco R, Campanozzi A, Pensabene L, Salvatore S, et al. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome in children: prevalence at diagnosis and at follow-up. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1099–103, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meleine M, Matricon J. Gender-related differences in irritable bowel syndrome: potential mechanisms of sex hormones. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6725–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, et al. Gastrointestinal transit: the effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1497–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ernst AR, Routh DK, Harper DC. Abdominal pain in children and symptoms of somatization disorder. J Pediatr Psychol. 1984;9:77–86. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/9.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahrer NE, Montano Z, Gold JI. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, somatization, and health-related quality of life in children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:808–16. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams AE, Czyzewski DI, Self MM, Shulman RJ. Are child anxiety and somatization associated with pain in pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Health Psychol. 2015;20:369–79. doi: 10.1177/1359105313502564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu L, Huang D, Shi L, Liang L, Xu T, Chang M, et al. Intestinal symptoms and psychological factors jointly affect quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:49. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao JC, Allen LB, Evans S, Lu Q, Myers CD, Zeltzer LK. Anxiety sensitivity and catastrophizing: associations with pain and somatization in nonclinical children. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:1085–94. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychol Med. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang L, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1686–701. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heitkemper MM, Chang L. Do fluctuations in ovarian hormones affect gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome? Gend Med. 2009;6(Suppl 2):152–67. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chogle A, Sztainberg M, Bass L, Youssef NN, Miranda A, Nurko S, et al. Accuracy of pain recall in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:288–91. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31824cf08a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]