Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine how patient satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to medical care influence functional improvement or deterioration (activity limitation stage transitions), institutionalization, or death among older adults.

DESIGN

A national representative sample with two year follow-up.

SETTING

Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) from calendar years 2001-2008.

PARTICIPANTS

Our study sample included 23,470 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older followed for two years.

INTERVENTIONS

Not applicable.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE(S)

A multinomial logistic regression model taking into account the complex survey design was used to examine the association between patient satisfaction with care coordination and quality and patient satisfaction with access to medical care and activity of daily living (ADL) stage transitions, institutionalization, or death after two years, adjusting for baseline socioeconomics and health-related characteristics.

RESULTS

Out of 23,470 Medicare beneficiaries, 14,979 (63.8% weighted) remained stable in ADL stage, 2,508 (10.7% weighted) improved, 3,210 (13.3% weighted) deteriorated, 582 (2.5% weighted) were institutionalized, and 2,281 (9.7% weighted) died. Beneficiaries who were in the top quartile of satisfaction with care coordination and quality were less likely to be institutionalized (adjusted relative risk ratio (RRR) = 0.68, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.54-0.86). Beneficiaries who were in the top quartile of satisfaction with access to medical care were less likely to functionally deteriorate (adjusted RRR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.79-0.97), be institutionalized (adjusted RRR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.56-0.92), or die (adjusted RRR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.75-0.98).

CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge of patient satisfaction with medical care and risk of functional deterioration may be helpful for monitoring and addressing disability-related healthcare disparities and the impact of ongoing policy changes among Medicare beneficiaries.

Keywords: Disabled persons, Medicare, Patient satisfaction, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Patient satisfaction is an important indicator of care quality.1 Satisfaction measures have been found to be useful in identifying patients’ unmet needs and are increasingly being used to evaluate healthcare system performance.2 Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), pay-for-performance strategies to incentivize improvements in healthcare quality rely on patient assessments of care provision.3 For older persons with disabilities and diverse healthcare and social needs, patient satisfaction ratings may identify opportunities for healthcare improvement. Information on the relationship between satisfaction, access to medical care, and patient outcomes can highlight specific accessibility and quality pitfalls for this vulnerable population and pinpoint areas that need to be improved within the current healthcare system.

Prior work demonstrates that a higher number of activity restrictions, measured by counts of limitations of activities of daily living (ADLs), is associated with greater dissatisfaction with the overall quality of healthcare.4 In addition, the presence of single types of disabling impairment (e.g., hearing or mental impairment, and chronic conditions) has been found to negatively influence patient satisfaction.5-8 We found that ADL or instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) limitations, by defined stages,9,10 were associated with dissatisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to medical care.11 These findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that higher disability burden is associated with decreased satisfaction with medical care. To our knowledge, no published research to date has examined whether or not decreased satisfaction with medical care influences transitions across activity limitation stages (functional improvement or deterioration), institutionalization, or death among older adults.

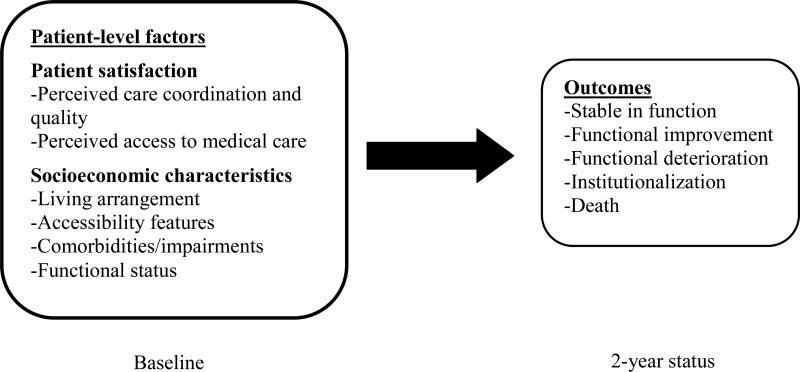

Our conceptual model is consistent with our prior work11 and represents the hypotheses examined in this study regarding how patient satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to medical care may relate to activity limitation stage transitions, institutionalization, or death (Figure 1). The objectives of the present study were 1) to describe how socioeconomic characteristics and health-related conditions influence functional improvement or deterioration (activity limitation stage transitions), institutionalization, or death at 2 years; and 2) to assess whether patient satisfaction with care and access to medical care at baseline were related to activity limitation stage transitions, institutionalization, or death at 2 years. We hypothesized that persons 65 years of age and older who report greater satisfaction with care and fewer access barriers would be less likely to deteriorate functionally, be institutionalized, or die. To generalize our results to the total elderly Medicare population, we used data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a systematic, representative sample.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model

METHODS

Study Sample from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS)

Our study sample included 23,470 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older participating in the MCBS from calendar years 2001-2008 followed for two years. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) conducts the MCBS through in-person beneficiary or proxy interviews.12-14 The majority of the sample responded for themselves, while 6.9% used proxies. Reasons for proxy use included hospitalization, temporary institutionalization, language problems, lack of mental or physical capability, absence of medical records, preference for the proxy to answer, or unavailability. The MCBS sample was randomly selected within geographic units and age stratum. The MCBS utilizes a rotating panel survey design in which four overlapping sample panels were drawn with staggered entry into the survey. Details regarding this study design are discussed in prior work.15 In this study, we used the Access to Care files at the time of the survey respondents’ first interview as baseline. All variables needed for the analysis were included in this file, the MCBS Key Record file, and the National Death Index. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at our university.

Baseline Covariates

Demographics included age (65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85 years and older as in prior work employing MCBS data16,17), gender, and race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), education (high school diploma or greater and less than a high school education), annual income (less than or equal to $25,000 and greater than $25,000), and supplemental insurance (Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee, private supplemental, other public supplemental, and Medicare only). We also assessed living arrangement (with spouse, with children, with others, alone, and retirement community). The presence or absence of accessibility features in the home including widened doorways, ramps, kitchen modifications, railings, easy open doors, accessible parking or drop-off sites, elevators or stair glides, alerting devices, or other special features was self- or proxy-reported. Comorbidities and impairments were determined by the respondents’ report of doctors’ diagnoses.

Patient Satisfaction

Satisfaction was assessed using a series of questions from the MCBS on care and access18 categorized under two patient satisfaction dimensions: 1) care coordination and quality; and 2) access barriers to medical care. The care coordination and quality dimension included five questions addressing “the overall quality of the medical care you have received in the last year,” “the information given to you about what was wrong with you,” “the follow-up care received by you after an initial treatment or operation,” “the concern of doctors for your overall health rather than just for an isolated symptom or disease,” and “getting all your medical care needs taken care of at the same location.” The access barriers to medical care dimension included three questions addressing “the availability of medical care at night and on weekends,” “the ease and convenience of getting to a doctor from where you live,” and “the out-of-pocket costs you paid for medical care.” Beneficiary or proxy answers to the questions were rated as: “very satisfied” (scored as 1), “satisfied” (scored as 2), “dissatisfied” (scored as 3), or “very dissatisfied” (scored as 4) during the baseline interview. Categorizing these questions under the two patient satisfaction dimensions (care coordination and quality; access barriers to medical care) is supported by factor analysis. Details regarding the derivation and application of these indicators of satisfaction are described elsewhere.19 Consistent with prior work,20 the scores for the three to five questions under each patient satisfaction dimension were used to calculate a summated score for each respondent. The average summated score corresponding to the upper quartile was considered most satisfied for patient satisfaction dimensions. For each patient satisfaction dimension, the highest quartile was compared to the three lower quartiles.

Stage Transition (Activities of Daily Living (ADL))

Stage transition for ADLs was the outcome for this study. The transition was assessed over two years of follow-up. Stage transitions were based on activity limitation stages (0 through IV) that were developed as previously described, institutionalization, or death information.10 Activity limitation stages were derived from responses to questions about ADLs that included eating, toileting, dressing, bathing/showering, getting in or out of bed/chairs, and walking. For each ADL, respondents were asked, “Because of a health condition, do you (or does the person you are answering for) have difficulty with...?”21,22 Stages represent both severity and the types of limitations experienced and specify clinically meaningful patterns of increasing difficulty with self-care skills.

At the end of the two year survey period each participant was categorized into one of five outcomes: stable, improved, or deteriorated in stage, institutionalized, or died. As in previous work,23 stable, improved, and deteriorated ADL function were defined as no change, decrease to a lower stage of ADL limitation, and increase to a higher stage of ADL limitation, respectively, comparing baseline to their stage two years later. Institutionalization was determined from the MCBS Key Record file that indicated which participants were interviewed in a facility two years later. Death was determined by linking MCBS data with the National Death Index.

Analysis

Statistical analysis started with the description of the characteristics of community-dwelling persons 65 years and older at baseline by stage transition outcomes. Then multinomial logistic regression models were fit to determine whether satisfaction with care coordination and quality or satisfaction with access to medical care was associated with the stage transition outcome. These two satisfaction dimensions were entered into two separate models adjusting for other baseline characteristics (initial ADL stages, sociodemographic characteristics, proxy respondent, and comorbidity and impairment). The model examining satisfaction with care coordination and quality included 22,849 beneficiaries because 621 beneficiaries reported “no experience” when asked about satisfaction with care coordination and quality and were therefore considered missing. The model examining satisfaction with access to medical care included 22,964 beneficiaries because 506 beneficiaries reported “no experience” when asked about satisfaction with access and were considered missing. Patient satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to medical care, our independent variables, were measured before our outcome assessed over two years of follow-up. Our outcome was a polychotomous variable with 5 possible values (stable in function, functional improvement, functional deterioration, institutionalization, or death). With “stable in function” as the reference category for the 5-state outcome, adjusted relative risk ratios (RRRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were reported. To aid interpretation, the RRR of death in comparing the two gender groups (male versus female) can be interpreted as the RR of death for a male patient divided by the RR of death for a female patient. For the covariate of initial ADL stage, we set stage ADL-I (mild limitation) as the reference category because improvement in ADL stage cannot occur at stage 0 and deterioration in ADL stage cannot occur at stage IV. In all analyses, the complex survey design such as weight, cluster, and strata were taken into account. All statistical analyses used the survey procedures of SAS® version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries 65 years and older in the MCBS sample at baseline can be found in Table 1. Out of 23,470 Medicare beneficiaries, 14,979 (63.8% weighted) remained stable in ADL stage; 2,508 (10.7% weighted) improved; 3,120 (13.3% weighted) deteriorated; 582 (2.5% weighted) were institutionalized; and 2,281 (9.7% weighted) died.

Table 1.

Analysis Showing Characteristics of Community-dwelling Persons 65 Years and Older at Baseline who Remained Stable, Experienced an Activity of Daily Living Stage Transition (Improvement or Deterioration), were Institutionalized, or Died within Two Years

| Total Column % N=23470 | Stable N (Weighted row %) 14979 (63.8) | Improved N (Weighted row %) 2508 (10.7) | Deteriorated N (Weighted row %) 3120 (13.3) | Institutionalized N (Weighted row %) 582 (2.5) | Died N (Weighted row %) 2281 (9.7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Activity of Daily Living Stage

| ||||||

| 0 | 16259 (69.3) | 12954 (82.2) | a | 2180 (12.1) | 230 (1.1) | 895 (4.6) |

| I | 3745 (16.0) | 1260 (34.0) | 1247 (36.0) | 623 (15.7) | 126 (2.8) | 489 (11.5) |

| II | 1888 (8.0) | 470 (24.6) | 627 (36.0) | 255 (13.5) | 127 (5.8) | 409 (20.0) |

| III | 1326 (5.6) | 250 (19.3) | 569 (46.4) | 62 (4.5) | 85 (5.6) | 360 (24.2) |

| IV | 252 (1.1) | 45 (18.0) | 65 (29.8) | a | 14 (5.1) | 128 (47.1) |

|

Very satisfied with care coordination and quality | ||||||

| No | 16803 (73.2) | 10383 (65.5) | 1906 (11.0) | 2289 (12.7) | 460 (2.2) | 1765 (8.7) |

| Yes | 6151 (26.8) | 4211 (72.0) | 575 (8.9) | 785 (11.6) | 106 (1.2) | 474 (6.3) |

|

Very satisfied with access | ||||||

| No | 17014 (73.7) | 10460 (65.1) | 1956 (11.2) | 2342 (12.9) | 461 (2.1) | 1795 (8.7) |

| Yes | 6056 (26.3) | 4228 (73.5) | 530 (8.1) | 744 (10.9) | 109 (1.4) | 445 (6.1) |

|

Age | ||||||

| 65-74 | 10558 (45.0) | 7861 (75.8) | 1063 (9.7) | 1090 (9.9) | 67 (0.5) | 477 (4.1) |

| 75-84 | 9422 (40.1) | 5733 (61.7) | 1070 (11.1) | 1402 (14.6) | 252 (2.6) | 965 (9.9) |

| ≥85 | 3490 (14.9) | 1385 (40.0) | 375 (10.7) | 628 (18.0) | 263 (7.5) | 839 (23.8) |

|

Gender | ||||||

| Male | 10181 (43.4) | 6817 (70.6) | 925 (8.7) | 1171 (10.5) | 157 (1.2) | 1111 (9.0) |

| Female | 13289 (56.6) | 8162 (65.2) | 1583 (11.5) | 1949 (13.7) | 425 (2.5) | 1170 (7.2) |

|

Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 19236 (82.0) | 12410 (68.4) | 1955 (9.7) | 2502 (11.9) | 513 (2.0) | 1856 (7.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1867 (8.0) | 1086 (61.3) | 244 (12.7) | 267 (13.8) | 42 (1.8) | 228 (10.4) |

| Hispanic | 1691 (7.2) | 1065 (65.6) | 233 (13.8) | 241 (13.4) | 18 (0.9) | 134 (6.4) |

| Other | 665 (2.8) | 411 (66.4) | 75 (10.9) | 108 (14.2) | a | 62 (7.2) |

|

Education | ||||||

| ≥High school diploma | 16581 (71.0) | 11251 (71.3) | 1619 (9.4) | 2058 (11.3) | 347 (1.6) | 1306 (6.4) |

| Below high school diploma | 6787 (29.0) | 3679 (57.4) | 883 (12.8) | 1050 (15.0) | 230 (2.7) | 945 (12.1) |

|

Annual income | ||||||

| ≤$25,000 | 12984 (55.3) | 7364 (59.8) | 1611 (12.3) | 1936 (14.3) | 443 (2.8) | 1630 (10.8) |

| >$25,000 | 10486 (44.7) | 7615 (75.8) | 897 (8.2) | 1184 (10.1) | 139 (1.0) | 651 (4.9) |

|

Supplemental insurance | ||||||

| Medicare and Medicaid-dual enrollee | 2879 (12.3) | 1354 (49.5) | 440 (15.7) | 500 (17.1) | 143 (4.2) | 442 (13.5) |

| Private-supplemental | 14294 (60.9) | 9575 (70.7) | 1403 (9.4) | 1808 (11.5) | 289 (1.5) | 1219 (6.9) |

| Others public supplemental | 404 (1.7) | 234 (59.6) | 44 (11.1) | 64 (15.5) | 13 (2.6) | 49 (11.3) |

| Medicare only | 5893 (25.1) | 3816 (68.5) | 621 (9.9) | 748 (11.9) | 137 (1.8) | 571 (8.0) |

|

Living arrangement | ||||||

| With spouse | 11732 (50.0) | 8200 (72.8) | 1156 (9.4) | 1402 (11.0) | 107 (0.7) | 867 (6.1) |

| With children | 2364 (10.1) | 1200 (54.1) | 298 (13.0) | 409 (16.6) | 71 (2.5) | 386 (13.7) |

| With others | 1112 (4.7) | 660 (62.9) | 132 (11.8) | 142 (12.2) | 36 (2.6) | 142 (10.5) |

| Alone | 6595 (28.1) | 4046 (65.2) | 719 (10.4) | 918 (12.8) | 242 (3.0) | 670 (8.6) |

| Retirement community | 1667 (7.1) | 873 (55.5) | 203 (12.0) | 249 (14.3) | 126 (6.5) | 216 (11.5) |

|

Home accessibility features | ||||||

| No | 13838 (59.0) | 9813 (73.8) | 1222 (8.5) | 1633 (10.8) | 197 (1.1) | 973 (5.8) |

| Yes | 9632 (41.0) | 5166 (57.1) | 1286 (13.2) | 1487 (14.7) | 385 (3.3) | 1308 (11.7) |

|

Beneficiary or proxy interview | ||||||

| Beneficiary | 21559 (91.9) | 14124 (68.9) | 2301 (10.2) | 2820 (12.1) | 477 (1.7) | 1837 (7.0) |

| Proxy | 1609 (6.9) | 656 (46.6) | 172 (10.9) | 265 (14.8) | 97 (5.2) | 419 (22.4) |

|

Comorbidities | ||||||

|

Alzheimer/dementia

| ||||||

| No | 22810 (97.2) | 14824 (68.5) | 2453 (10.3) | 3001 (12.1) | 484 (1.6) | 2048 (7.4) |

| Yes | 660 (2.8) | 155 (25.0) | 55 (8.5) | 119 (17.8) | 98 (15.0) | 233 (33.6) |

|

Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | ||||||

| No | 21132 (90.0) | 13700 (68.6) | 2172 (9.9) | 2748 (11.9) | 536 (1.9) | 1976 (7.6) |

| Yes | 2338 (10.0) | 1279 (57.4) | 336 (14.2) | 372 (15.3) | 46 (1.6) | 305 (11.4) |

|

Complete/partial paralysis | ||||||

| No | 22842 (97.3) | 14697 (68.1) | 2396 (10.1) | 3026 (12.2) | 550 (1.9) | 2173 (7.8) |

| Yes | 628 (2.7) | 282 (47.5) | 112 (18.5) | 94 (14.8) | 32 (4.3) | 108 (14.9) |

|

Diabetes/high blood sugar | ||||||

| No | 18420 (78.5) | 12244 (70.3) | 1791 (9.2) | 2283 (11.3) | 442 (1.8) | 1660 (7.3) |

| Yes | 5050 (21.5) | 2735 (57.6) | 717 (14.1) | 837 (15.7) | 140 (2.3) | 621 (10.3) |

|

Emphysema/asthma/Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | ||||||

| No | 20314 (86.6) | 13358 (69.5) | 2012 (9.5) | 2655 (12.0) | 520 (2.0) | 1769 (7.1) |

| Yes | 3156 (13.4) | 1621 (55.1) | 496 (15.6) | 465 (14.1) | 62 (1.6) | 512 (13.6) |

|

Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 9582 (40.8) | 6577 (72.8) | 787 (7.7) | 1099 (10.4) | 263 (2.0) | 856 (7.1) |

| Yes | 13888 (59.2) | 8402 (63.8) | 1721 (12.1) | 2021 (13.6) | 319 (1.8) | 1425 (8.6) |

|

Mental/psychiatric disorder | ||||||

| No | 22118 (94.2) | 14329 (68.5) | 2270 (9.9) | 2900 (12.0) | 510 (1.8) | 2109 (7.8) |

| Yes | 1352 (5.8) | 650 (51.3) | 238 (17.3) | 220 (16.0) | 72 (4.2) | 172 (11.2) |

|

Mental retardation | ||||||

| No | 23400 (99.7) | 14947 (67.6) | 2496 (10.2) | 3109 (12.3) | 572 (1.9) | 2276 (8.0) |

| Yes | 70 (0.3) | 32 (50.0) | 12 (17.9) | 11 (13.2) | a | a |

|

Myocardial infarction/heart attack | ||||||

| No | 20258 (86.3) | 13262 (69.2) | 2055 (9.8) | 2646 (12.0) | 501 (1.9) | 1794 (7.2) |

| Yes | 3212 (13.7) | 1717 (56.4) | 453 (13.9) | 474 (14.2) | 81 (2.1) | 487 (13.5) |

|

Other heart conditions | ||||||

| No | 20291 (86.5) | 13237 (68.9) | 2027 (9.6) | 2643 (12.0) | 509 (1.9) | 1875 (7.6) |

| Yes | 3179 (13.5) | 1742 (58.2) | 481 (15.0) | 477 (14.1) | 73 (1.9) | 406 (10.8) |

|

Parkinson's disease | ||||||

| No | 23176 (98.8) | 14876 (67.9) | 2471 (10.3) | 3064 (12.2) | 560 (1.9) | 2205 (7.8) |

| Yes | 294 (1.2) | 103 (35.6) | 37 (11.2) | 56 (21.9) | 22 (7.2) | 76 (24.0) |

|

Severe hearing impairment/deaf | ||||||

| No | 21699 (92.5) | 14180 (68.9) | 2227 (9.9) | 2822 (12.0) | 506 (1.8) | 1964 (7.5) |

| Yes | 1771 (7.5) | 799 (48.5) | 281 (16.2) | 298 (16.4) | 76 (3.5) | 317 (15.4) |

|

Severe vision impairment/no usable vision | ||||||

| No | 21701 (92.5) | 14267 (69.3) | 2196 (9.7) | 2799 (11.9) | 500 (1.8) | 1939 (7.4) |

| Yes | 1769 (7.5) | 712 (42.8) | 312 (18.2) | 321 (17.7) | 82 (4.1) | 342 (17.2) |

|

Stroke/brain hemorrhage | ||||||

| No | 20868 (88.9) | 13813 (69.7) | 2094 (9.7) | 2688 (11.8) | 470 (1.7) | 1803 (7.1) |

| Yes | 2602 (11.1) | 1166 (48.1) | 414 (15.7) | 432 (16.1) | 112 (3.7) | 478 (16.3) |

Cannot display since cell size is less than 11

Note: care coordination and quality was missing = 516; access barriers to medical care was missing = 400; race/ethnicity was missing = 11; education was missing = 102; Beneficiary or proxy interview was missing=302; Activity of Daily Living Stage was missing = 2;

Baseline covariates and ADL stage transitions

For baseline covariates, Tables 2 and 3 show the same statistical significance and direction of association. Compared to beneficiaries 65-74 years of age, beneficiaries 75 years of age and older were significantly less likely to improve in function and more likely to functionally deteriorate, be institutionalized, or die. Compared to women, men were significantly less likely to functionally deteriorate but were more likely to die. Compared to Non-Hispanic whites, Non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were less likely to be institutionalized. Hispanics and persons specifying ‘Other ‘were less likely to die compared to Non-Hispanic whites. Beneficiaries who had an annual income greater than $25,000 were less likely to functionally deteriorate, be institutionalized, or die compared to beneficiaries who had an annual income less than or equal to $25,000. Compared to beneficiaries who had private-supplemental insurance, beneficiaries who were Medicare and Medicaid-dual enrollees were more likely to functionally deteriorate, be institutionalized, or die. Compared to beneficiaries who lived with a spouse, beneficiaries who lived with others, alone, or in a retirement community were more likely to be institutionalized and beneficiaries who lived alone or with children were more likely to die. Compared to beneficiaries who lived with a spouse, beneficiaries who lived with others were less likely to improve. Compared to beneficiaries who did not have home accessibility features, beneficiaries with home accessibility features were less likely to improve and more likely to functionally deteriorate, be institutionalized, or die. Compared to beneficiaries who did not use a proxy respondent, beneficiaries who used a proxy were significantly less likely to improve in function and more likely to functionally deteriorate or die. Compared to the absence of medical comorbidity, specific medical comorbidities were also associated with a decreased likelihood of improvement in function and an increased likelihood of functional deterioration, institutionalization, and death. Alzheimer's/dementia was the condition most strongly associated with functional deterioration, institutionalization, and death in models controlling both for care coordination and quality and access to medical care. Parkinson's disease was strongly associated with functional deterioration, institutionalization, and death. Diabetes was associated with all adverse outcomes as well. Myocardial infarction was associated with death but not the other adverse outcomes.

Table 2.

The Association of Satisfaction with Care Coordination and Quality with Activity of Daily Living Stage Transition (Improvement or Deterioration), Institutionalization, or Death within Two Years Adjusting for other Covariates (eligible sample size=22556)

| Improvement | Deterioration | Institutionalized | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRRa (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Very satisfied with care quality (ref: not) | 0.96 (0.83-1.11) | 0.591 | 0.96 (0.87-1.07) | 0.452 | 0.68 (0.54-0.86) | 0.001 | 0.88 (0.78-1.00) | 0.058 |

|

Activity of Daily Living Stage (ref: Stage I) | ||||||||

| Stage 0 | omitted—ceiling effect | 0.50 (0.44-0.57) | <.0001 | 0.30 (0.23-0.38) | <.0001 | 0.27 (0.23-0.31) | <.0001 | |

| Stage II | 1.55 (1.32-1.81) | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.72-1.09) | 0.238 | 1.70 (1.25-2.31) | 0.001 | 1.85 (1.53-2.26) | <.0001 |

| Stage III | 2.68 (2.21-3.25) | <.0001 | 0.32 (0.23-0.44) | <.0001 | 2.01 (1.40-2.89) | 0.0002 | 2.43 (1.94-3.05) | <.0001 |

| Stage IV | 2.57 (1.69-3.92) | <.0001 | omitted—floor effect | 0.78 (0.33-1.87) | 0.579 | 3.44 (2.22-5.35) | <.0001 | |

|

Age (ref: 65-74) | ||||||||

| 75-84 | 0.81 (0.71-0.92) | 0.002 | 1.50 (1.36-1.65) | <.0001 | 3.54 (2.60-4.81) | <.0001 | 2.12 (1.85-2.43) | <.0001 |

| ≥85 | 0.65 (0.54-0.78) | <.0001 | 2.41 (2.10-2.76) | <.0001 | 9.02 (6.50-12.53) | <.0001 | 5.29 (4.49-6.22) | <.0001 |

| Male (ref: female) | 0.99 (0.87-1.13) | 0.902 | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.70-1.12) | 0.300 | 1.81 (1.60-2.05) | <.0001 |

|

Race (ref: Non-Hispanic white) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.10 (0.86-1.39) | 0.449 | 0.90 (0.76-1.08) | 0.272 | 0.23 (0.13-0.40) | <.0001 | 0.52 (0.40-0.66) | <.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.17 (0.94-1.46) | 0.154 | 1.05 (0.88-1.26) | 0.572 | 0.63 (0.42-0.95) | 0.028 | 1.01 (0.82-1.26) | 0.905 |

| Other | 0.98 (0.70-1.39) | 0.917 | 1.03 (0.79-1.34) | 0.821 | 0.28 (0.11-0.69) | 0.006 | 0.67 (0.48-0.95) | 0.023 |

| No high school diploma (ref: ≥High school diploma) | 0.99 (0.86-1.13) | 0.856 | 1.20 (1.07-1.34) | 0.001 | 1.15 (0.92-1.43) | 0.228 | 1.26 (1.11-1.43) | 0.0004 |

| Income >$25,000 (ref: ≤$25,000) | 1.00 (0.86-1.15) | 0.969 | 0.82 (0.74-0.91) | 0.0002 | 0.67 (0.52-0.86) | 0.002 | 0.65 (0.57-0.75) | <.0001 |

|

Insurance (ref: Private support) | ||||||||

| Dual eligible | 0.88 (0.72-1.07) | 0.189 | 1.31 (1.12-1.54) | 0.001 | 2.06 (1.56-2.71) | <.0001 | 1.30 (1.08-1.56) | 0.007 |

| Medicare only | 1.00 (0.86-1.16) | 0.981 | 1.03 (0.93-1.15) | 0.546 | 1.17 (0.93-1.48) | 0.186 | 1.10 (0.96-1.25) | 0.172 |

| Others-public | 0.96 (0.62-1.48) | 0.843 | 1.10 (0.80-1.51) | 0.545 | 1.21 (0.66-2.20) | 0.536 | 1.31 (0.88-1.97) | 0.186 |

|

Living arrangement (ref: With spouse) | ||||||||

| Alone | 0.98 (0.84-1.15) | 0.836 | 0.96 (0.85-1.07) | 0.421 | 2.53 (1.88-3.40) | <.0001 | 1.20 (1.04-1.39) | 0.015 |

| Retirement community | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) | 0.765 | 0.92 (0.77-1.10) | 0.376 | 3.89 (2.79-5.42) | <.0001 | 1.17 (0.96-1.44) | 0.128 |

| With children | 0.85 (0.69-1.04) | 0.116 | 1.13 (0.96-1.33) | 0.139 | 1.41 (0.96-2.08) | 0.079 | 1.27 (1.05-1.53) | 0.013 |

| With others | 0.75 (0.56-0.99) | 0.043 | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | 0.508 | 1.89 (1.18-3.03) | 0.008 | 1.23 (0.95-1.59) | 0.118 |

| Having home accessibility features (ref: No) | 0.81 (0.72-0.92) | 0.001 | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) | <.0001 | 1.42 (1.14-1.76) | 0.002 | 1.24 (1.10-1.39) | 0.0003 |

| Proxy (ref: sample beneficiary responded) | 0.77 (0.60-0.99) | 0.041 | 1.34 (1.12-1.59) | 0.001 | 1.30 (0.92-1.83) | 0.134 | 1.58 (1.31-1.91) | <.0001 |

|

Comorbidities (ref: no) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 1.19 (1.05-1.35) | 0.009 | 1.18 (1.08-1.30) | 0.001 | 0.81 (0.67-0.99) | 0.0390 | 1.04 (0.93-1.17) | 0.489 |

| Myocardial infarction/heart attack | 1.04 (0.88-1.22) | 0.678 | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) | 0.592 | 1.04 (0.77-1.39) | 0.822 | 1.33 (1.14-1.55) | 0.0003 |

| Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | 1.03 (0.86-1.24) | 0.755 | 1.20 (1.03-1.40) | 0.017 | 0.73 (0.51-1.06) | 0.097 | 1.05 (0.88-1.26) | 0.608 |

| Other heart conditions | 1.13 (0.97-1.33) | 0.119 | 1.13 (1.00-1.29) | 0.057 | 0.87 (0.66-1.16) | 0.342 | 1.15 (0.99-1.33) | 0.069 |

| Stroke/brain hemorrhage | 0.90 (0.76-1.07) | 0.234 | 1.31 (1.13-1.51) | 0.0004 | 1.34 (1.03-1.76) | 0.031 | 1.35 (1.15-1.59) | 0.0002 |

| Diabetes/high blood sugar | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | 0.031 | 1.42 (1.27-1.57) | <.0001 | 1.48 (1.17-1.87) | 0.001 | 1.27 (1.11-1.44) | 0.0003 |

| Mental retardation | 0.54 (0.22-1.30) | 0.169 | 0.86 (0.42-1.77) | 0.684 | 2.71 (1.11-6.59) | 0.028 | 0.32 (0.08-1.27) | 0.105 |

| Alzheimer/dementia | 0.80 (0.54-1.18) | 0.262 | 2.28 (1.71-3.03) | <.0001 | 8.72 (5.96-12.76) | <.0001 | 3.01 (2.26-4.01) | <.0001 |

| Mental/psychiatric disorder | 1.03 (0.83-1.29) | 0.789 | 1.43 (1.19-1.72) | 0.0001 | 1.86 (1.35-2.55) | 0.0001 | 1.13 (0.88-1.44) | 0.342 |

| Parkinson's disease | 0.39 (0.25-0.63) | <.0001 | 2.26 (1.48-3.45) | 0.0002 | 2.15 (1.17-3.93) | 0.013 | 1.60 (1.04-2.45) | 0.031 |

| Emphysema/asthma/COPD | 0.95 (0.81-1.11) | 0.525 | 1.27 (1.11-1.45) | 0.0004 | 0.82 (0.61-1.10) | 0.189 | 1.80 (1.56-2.07) | <.0001 |

| Complete/partial paralysis | 0.66 (0.49-0.89) | 0.006 | 1.11 (0.84-1.48) | 0.459 | 1.24 (0.76-2.02) | 0.388 | 0.75 (0.54-1.03) | 0.077 |

| Severe vision impairment /no usable vision | 0.90 (0.75-1.09) | 0.280 | 1.39 (1.18-1.64) | <.0001 | 1.09 (0.81-1.46) | 0.573 | 1.15 (0.96-1.38) | 0.135 |

| Severe hearing impairment/deaf | 1.18 (0.97-1.44) | 0.097 | 1.37 (1.16-1.62) | 0.0002 | 1.11 (0.81-1.53) | 0.524 | 1.06 (0.88-1.27) | 0.550 |

RRR=relative risk ratio; CI=confidence interval; COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Table 3.

The Association of Satisfaction with Access to Medical Care with Activity of Daily Living Stage Transition (Improvement or Deterioration), Institutionalization, or Death within Two Years Adjusting for Other Covariates (eligible sample size= 22669)

| Improvement | Deterioration | Institutionalized | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRRa (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | RRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Very satisfied with access care (ref: Not satisfied) | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.419 | 0.87 (0.79-0.97) | 0.009 | 0.72 (0.56-0.92) | 0.008 | 0.86 (0.75-0.98) | 0.026 |

|

ADL (ref: Stage I) | ||||||||

| Stage 0 | omitted—ceiling effect | 0.51 (0.44-0.57) | <.0001 | 0.30 (0.23-0.39) | <.0001 | 0.27 (0.24-0.32) | <.0001 | |

| Stage II | 1.54 (1.32-1.81) | <.0001 | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | 0.232 | 1.74 (1.28-2.36) | 0.0004 | 1.86 (1.53-2.26) | <.0001 |

| Stage III | 2.67 (2.20-3.24) | <.0001 | 0.32 (0.23-0.44) | <.0001 | 2.02 (1.41-2.91) | 0.0002 | 2.43 (1.94-3.05) | <.0001 |

| Stage IV | 2.56 (1.68-3.90) | <.0001 | omitted—floor effect | 0.81 (0.34-1.92) | 0.628 | 3.48 (2.24-5.41) | <.0001 | |

|

Age (ref: 65-74) | ||||||||

| 75-84 | 0.81 (0.71-0.92) | 0.002 | 1.51 (1.37-1.66) | <.0001 | 3.62 (2.66-4.92) | <.0001 | 2.13 (1.86-2.44) | <.0001 |

| ≥85 | 0.64 (0.54-0.77) | <.0001 | 2.43 (2.12-2.78) | <.0001 | 9.29 (6.70-12.87) | <.0001 | 5.28 (4.49-6.22) | <.0001 |

| Male (ref: female) | 0.99 (0.87-1.14) | 0.931 | 0.79 (0.72-0.88) | <.0001 | 0.89 (0.70-1.12) | 0.309 | 1.81 (1.60-2.05) | <.0001 |

|

Race (ref: Non-Hispanic white) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.11 (0.87-1.41) | 0.397 | 0.91 (0.76-1.09) | 0.286 | 0.23 (0.13-0.41) | <.0001 | 0.52 (0.41-0.67) | <.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.17 (0.94-1.45) | 0.169 | 1.05 (0.88-1.25) | 0.580 | 0.64 (0.43-0.97) | 0.034 | 1.01 (0.82-1.26) | 0.906 |

| Other | 1.02 (0.72-1.43) | 0.920 | 1.05 (0.80-1.36) | 0.742 | 0.35 (0.15-0.82) | 0.016 | 0.70 (0.49-0.98) | 0.037 |

| No high school diploma (ref: ≥High school diploma) | 0.99 (0.86-1.13) | 0.873 | 1.19 (1.07-1.32) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.91-1.42) | 0.257 | 1.25 (1.10-1.42) | 0.001 |

| Income >$25,000 (ref: ≤$25,000) | 1.01 (0.87-1.16) | 0.948 | 0.82 (0.74-0.92) | 0.0003 | 0.68 (0.53-0.87) | 0.003 | 0.65 (0.57-0.75) | <.0001 |

|

Insurance (ref: Private support) | ||||||||

| Dual eligible | 0.88 (0.73-1.07) | 0.203 | 1.30 (1.11-1.53) | 0.001 | 2.04 (1.55-2.69) | <.0001 | 1.29 (1.07-1.55) | 0.008 |

| Medicare only | 0.98 (0.85-1.14) | 0.804 | 1.03 (0.92-1.15) | 0.633 | 1.17 (0.93-1.47) | 0.192 | 1.08 (0.95-1.24) | 0.240 |

| Others-public | 0.95 (0.62-1.47) | 0.825 | 1.10 (0.80-1.50) | 0.570 | 1.21 (0.66-2.20) | 0.541 | 1.31 (0.87-1.96) | 0.191 |

|

Living arrangement (ref: With spouse) | ||||||||

| Alone | 1.00 (0.85-1.17) | 0.993 | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | 0.375 | 2.57 (1.91-3.46) | <.0001 | 1.21 (1.05-1.41) | 0.010 |

| Retirement community | 1.00 (0.80-1.26) | 0.997 | 0.94 (0.78-1.12) | 0.462 | 3.97 (2.84-5.54) | <.0001 | 1.19 (0.97-1.46) | 0.104 |

| With children | 0.85 (0.70-1.05) | 0.127 | 1.14 (0.97-1.34) | 0.127 | 1.41 (0.96-2.08) | 0.082 | 1.25 (1.04-1.52) | 0.019 |

| With others | 0.75 (0.57-1.00) | 0.049 | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | 0.515 | 1.92 (1.20-3.07) | 0.006 | 1.22 (0.95-1.59) | 0.125 |

| Having home accessibility features (ref: No) | 0.82 (0.72-0.93) | 0.002 | 1.30 (1.19-1.43) | <.0001 | 1.41 (1.13-1.75) | 0.002 | 1.24 (1.10-1.39) | 0.0004 |

| Proxy (ref: sample beneficiary responded) | 0.78 (0.61-0.99) | 0.044 | 1.34 (1.12-1.60) | 0.0011 | 1.26 (0.89-1.76) | 0.191 | 1.57 (1.30-1.89) | <.0001 |

|

Comorbidities (ref: no) | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 1.19 (1.05-1.36) | 0.008 | 1.19 (1.08-1.30) | 0.0003 | 0.80 (0.65-0.97) | 0.023 | 1.05 (0.93-1.18) | 0.430 |

| Myocardial infarction/heart attack | 1.03 (0.87-1.22) | 0.740 | 1.04 (0.90-1.19) | 0.616 | 1.03 (0.76-1.38) | 0.862 | 1.32 (1.13-1.54) | 0.0004 |

| Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | 1.03 (0.86-1.25) | 0.729 | 1.21 (1.04-1.40) | 0.015 | 0.73 (0.51-1.05) | 0.091 | 1.05 (0.87-1.26) | 0.617 |

| Other heart conditions | 1.13 (0.97-1.33) | 0.124 | 1.13 (0.99-1.28) | 0.065 | 0.87 (0.65-1.15) | 0.318 | 1.14 (0.99-1.33) | 0.076 |

| Stroke/brain hemorrhage | 0.90 (0.76-1.07) | 0.233 | 1.31 (1.13-1.52) | 0.0003 | 1.35 (1.03-1.77) | 0.028 | 1.36 (1.16-1.60) | 0.0002 |

| Diabetes/high blood sugar | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | 0.034 | 1.42 (1.27-1.58) | <.0001 | 1.48 (1.18-1.87) | 0.001 | 1.27 (1.11-1.44) | 0.0003 |

| Mental retardation | 0.54 (0.22-1.30) | 0.167 | 0.87 (0.42-1.79) | 0.703 | 2.93 (1.24-6.91) | 0.014 | 0.32 (0.08-1.26) | 0.104 |

| Alzheimer/dementia | 0.80 (0.54-1.19) | 0.274 | 2.29 (1.72-3.05) | <.0001 | 8.68 (5.94-12.69) | <.0001 | 3.04 (2.29-4.05) | <.0001 |

| Mental/psychiatric disorder | 1.04 (0.84-1.30) | 0.714 | 1.44 (1.20-1.73) | 0.0001 | 1.87 (1.37-2.57) | <.0001 | 1.14 (0.89-1.45) | 0.309 |

| Parkinson's disease | 0.39 (0.25-0.63) | <.0001 | 2.26 (1.48-3.45) | 0.0001 | 2.19 (1.20-4.00) | 0.011 | 1.61 (1.05-2.46) | 0.029 |

| Emphysema/asthma/COPD | 0.93 (0.80-1.09) | 0.390 | 1.26 (1.10-1.44) | 0.001 | 0.81 (0.60-1.09) | 0.157 | 1.78 (1.55-2.05) | <.0001 |

| Complete/partial paralysis | 0.66 (0.49-0.89) | 0.006 | 1.11 (0.84-1.48) | 0.466 | 1.24 (0.76-2.02) | 0.383 | 0.74 (0.54-1.03) | 0.075 |

| Severe vision impairment /no usable vision | 0.91 (0.75-1.09) | 0.3105 | 1.38 (1.17-1.63) | 0.0001 | 1.09 (0.82-1.47) | 0.547 | 1.16 (0.96-1.39) | 0.117 |

| Severe hearing impairment/deaf | 1.17 (0.96-1.42) | 0.128 | 1.35 (1.14-1.60) | 0.0004 | 1.10 (0.80-1.52) | 0.542 | 1.05 (0.88-1.26) | 0.572 |

RRR = relative risk ratio; CI = confidence interval; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Satisfaction with care coordination and quality and ADL stage transitions

Table 2 shows satisfaction with care coordination and quality along with other prognostic factors associated with ADL stage transitions, institutionalization, or death. Compared to beneficiaries who were in the lower three quartiles of satisfaction with care coordination and quality, beneficiaries who were in the top quartile were less likely to be institutionalized (adjusted RRR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.54-0.86).

Satisfaction with access to medical care and IADL stage transitions

Table 3 shows satisfaction with access to medical care and IADL stage transitions, institutionalization, or death. Compared to beneficiaries who were in the lower three quartiles of satisfaction with access to medical care, beneficiaries who were in the top quartile were less likely to functionally deteriorate (adjusted RRR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.79-0.97), be institutionalized (adjusted RRR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.556-0.92), or die (adjusted RRR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.75-0.98).

DISCUSSION

Our principal finding is that satisfaction relative to care coordination and quality and access to medical care is associated with functional deterioration, institutionalization, or death. Specifically, compared to beneficiaries in the bottom three quartiles of satisfaction with care coordination and quality, beneficiaries in the top quartile were less likely to be institutionalized at 2 years. Compared to beneficiaries in the bottom three quartiles of satisfaction with access to medical care, beneficiaries in the top quartile were less likely to functionally deteriorate, be institutionalized, or die at 2 years. After accounting for baseline function, our findings suggest that satisfaction levels may predict future outcomes.

Consistent with previous work,23 the likelihood of 2-year activity limitation stage transitions significantly differed based on age, gender, ethnicity, education, annual income, supplemental insurance, living arrangement, and the presence or absence of specific medical conditions. Our study showed that the presence of home accessibility features was associated with less functional improvement, and more functional deterioration, institutionalization, or death. Other researchers have found that environmental modifications are beneficial.24 Perceptions of need, specificity of chronic condition, and level of stage limitation may influence the role of home accessibility features in prognoses.21,25

Prior work has found that patient satisfaction is associated with sociodemographic characteristics,26 healthcare utilization and expenditures,27 and aspects of medical encounters (interactional dynamics and quality of care).28,29 In addition, patient satisfaction has been found to be associated with indicators of the type and severity of medical conditions including activity limitation stages,11 disabling conditions,5,6 and mortality.27 Our work provides new critical insight into the association between patient satisfaction and functional stability, improvement, deterioration, institutionalization, and death. Factors associated with satisfaction with access to care, including sociodemographic characteristics, have been identified, previously.30,31 Institutionalization has been linked with factors such as demographic characteristics, health status, and social support.32 Our work extends findings by evaluating the relationship between satisfaction and stage transitions, institutionalization, or death controlling for various other factors. This work may inform the identification of surveillance measures for use within the existing structure of the MCBS and administrative evaluation databases of large healthcare systems for monitoring and addressing disability-related healthcare disparities.

Pay for performance health care delivery models are widely employed and often use satisfaction as a performance indicator.33,34 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid is exploring the use of satisfaction as a key quality indicator for Medicare payments. Our findings provide additional support for an association between patient satisfaction and outcomes. However, the effectiveness of satisfaction as a payment metric in improving patient care has shown mixed results.35 Further investigation is needed to aid in the development of reimbursement programs incorporating satisfaction metrics that can foster quality service provision.

A myriad of complex mechanisms may underlie the relationship between satisfaction and functional improvement, deterioration, institutionalization, and death such as disease severity, presence of a disabling condition, living environment and circumstances, insurance coverage, and financial status. Access to medical care may play a particularly important role in investigating this association. It is notable that while satisfaction may influence functional improvement, deterioration, institutionalization, and death, such transitions may also influence satisfaction constituting a bi-directional relationship. Uncovering and understanding these relationships is an important area for future inquiry.

The patterns of the association of specific medical conditions with functional deterioration, institutionalization, and death are clinically intuitive. For instance, Alzheimer's disease or dementia as it is associated with progressive cognitive decline is a logical cause of functional deterioration and transitions to more limited ADL stages, institutionalization, and death.36 Parkinson's disease, a motor system disorder, is associated with further functional deterioration and institutionalization but not with death.37 Diabetes which can be treated to maintain blood glucose levels close to normal is less strongly but consistently associated with all adverse outcome transitions.38 It is not surprising that a history of myocardial infarction was associated with death but not the other adverse outcomes.39 Knowledge of these associations may point the way to health service initiatives that support elders who are expected to experience functional deterioration. It may also be used to guide policy makers and health system administrators in the allocation of in-home services to delay or prevent nursing home admission.

Study Limitations

Several study limitations should be considered. While the MCBS sample is intended to be representative of the entire Medicare population, our analyses did not include beneficiaries less than 65 years of age. There is the potential for all the sources of error associated with retrospective interview data including imperfect recall and response bias. Study data are based on self-reports including the reporting of medical comorbidity. Identification of medical comorbidity is complex and each method used to ascertain the presence of medical illnesses has limitations. Respondents may not know or be able to recall their diagnoses and may misuse terms; however Medicare claims describe utilization of services and are often incomplete measures of comorbidity. For example, relying on claims for comorbidities will miss persons who did not receive healthcare for a particular condition within the specified time period. Even with confidence in our assessments, misspecification of the model is still a possibility, such as when important variables have not been included. We attempted to take care in adjusting our estimates of association for potentially influential characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

There is widespread belief and recent evidence that disabilities place patients at risk for inequities in healthcare and adverse health outcomes.40 This evidence is stimulating greater efforts for public health surveillance, with calls to improve access to healthcare and human services, to apply disability data in decision-making, and to enhance workforce capacity. Our findings that perceptions of satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to medical care are associated with a lower risk of functional decline, institutionalization, and death supports the notion that healthcare systems should direct more attention to the identification, enhancement, and monitoring of those facets of their systems that drive satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute PCORI Project Program Award AD-12-11-4567 and by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG040105 and R01HD074756). Dr. Bogner was supported by an American Heart Association Award #13GRNT17000021.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADL

activity of daily living

- MCBS

Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- RRR

relative risk ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Interest: The authors have no financial or any other kind of conflicts of interest to declare.

Reprints are not available from the authors.

Suppliers

SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, 100 SAS Campus Dr, Cary, NC 27513.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988 Sep 23-30;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Soc Sci Med. 1994 Feb;38(4):509–516. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014 Jul 5;384(9937):75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha A, Patrick DL, MacLehose RF, Doctor JN, Chan L. Dissatisfaction with medical services among Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2002 Oct;83(10):1335–1341. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Physical and sensory functioning over time and satisfaction with care: the implications of getting better or getting worse. Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec;39(6 Pt 1):1635–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbach ML. Access and satisfaction within the disabled Medicare population. Health Care Financ Rev. 1995;17(2):147–167. Winter. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett DD, Koul R, Coppola NM. Satisfaction with health care among people with hearing impairment: a survey of Medicare beneficiaries. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(1):39–48. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.777803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Quality dimensions that most concern people with physical and sensory disabilities. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Sep 22;163(17):2085–2092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dynamic Tools to Measure Health from the Patient Perspective (PROMIS) National Institute of Health (Online); [September 14, 2015]. Available at: http://www.nihpromis.org/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stineman MG, Streim JE, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Schussler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Xie D. Activity Limitation Stages empirically derived for Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental ADL in the U.S. Adult community-dwelling Medicare population. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014 Nov;6(11):976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.001. quiz 987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogner HR, de Vries McClintock HF, Hennessy S, et al. Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Care Among Older Adults According to Activity Limitation Stages. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.06.005. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (online); [September 10, 2015]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Access to Care Introduction for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [September 7, 2015]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/MCBS/. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Chapter 1, Part 4 (Sections 200 – 310.1) Coverage Determinations (Rev. 135, 09-22-11) Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [September 8, 2015]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_part4.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Doubeni CA, Chen Y, Rao SR. Methodological issues in using multiple years of the Medicare current beneficiary survey. Medicare & medicaid research review. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.5600/mmrr.002.01.a04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennessy S, Kurichi JE, Pan Q, et al. Disability Stage is an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality in Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years and Older. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2015 Dec;7(12):1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Andreski PM, et al. Trends in late-life activity limitations in the United States: an update from five national surveys. Demography. 2013 Apr;50(2):661–671. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohr KN, Schroeder SA. A strategy for quality assurance in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 1990 Mar 8;322(10):707–712. doi: 10.1056/nejm199003083221031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Kasper JD. Assessment of medical care by elderly people: general satisfaction and physician quality. Health Serv Res. 1998 Feb;32(6):741–758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogner HR, de Vries McClintock HF, Hennessy S, et al. Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Care Among Older Adults According to Activity Limitation Stages. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015 Oct;96(10):1810–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Saliba D, Streim J. Activity of daily living staging, chronic health conditions, and perceived lack of home accessibility features for elderly people living in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Mar;59(3):454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stineman MG, Zhang G, Kurichi JE, et al. Prognosis for functional deterioration and functional improvement in late life among community-dwelling persons. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2013 May;5(5):360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu SY, Lapane KL. Residential modifications and decline in physical function among community-dwelling older adults. Gerontologist. 2009 Jun;49(3):344–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stineman MG, Ross RN, Maislin G, Gray D. Population-based study of home accessibility features and the activities of daily living: clinical and policy implications. Disabil Rehabil. 2007 Aug 15;29(15):1165–1175. doi: 10.1080/09638280600976145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall JA, Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(7):811–818. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Mar 12;172(5):405–411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clever SL, Jin L, Levinson W, Meltzer DO. Does doctor-patient communication affect patient satisfaction with hospital care? Results of an analysis with a novel instrumental variable. Health Serv Res. 2008 Oct;43(5 Pt 1):1505–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Dec 2;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kontopantelis E, Roland M, Reeves D. Patient experience of access to primary care: identification of predictors in a national patient survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jatulis DE, Bundek NI, Legorreta AP. Identifying predictors of satisfaction with access to medical care and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 1997;12(1):11–18. doi: 10.1177/0885713X9701200103. Spring. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Brahler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010 Jan;39(1):31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal MB, Landon BE, Normand SL, Frank RG, Epstein AM. Pay for performance in commercial HMOs. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 2;355(18):1895–1902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chien AT, Chin MH, Alexander GC, Tang H, Peek ME. Physician financial incentives and care for the underserved in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2014 Feb;20(2):121–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Layton TJ, Ryan AM. Higher Incentive Payments in Medicare Advantage's Pay-for-Performance Program Did Not Improve Quality But Did Increase Plan Offerings. Health Serv Res. Dec. 2015;50(6):1810–1828. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jicha GA, Carr SA. Conceptual evolution in Alzheimer's disease: implications for understanding the clinical phenotype of progressive neurodegenerative disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2010;19(1):253–272. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maetzler W, Liepelt I, Berg D. Progression of Parkinson's disease in the clinical phase: potential markers. Lancet neurology. 2009 Dec;8(12):1158–1171. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [September 10 2015]. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/factsheet11.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannel WB, Sorlie P, McNamara PM. Prognosis after initial myocardial infarction: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol. 1979 Jul;44(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015 Apr;105(Suppl 2):S198–206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]