Abstract

Sweat glands are critical for thermoregulation. The single tubular structure of sweat glands has a lower secretory portion and an upper reabsorptive duct leading to the secretory pore in the skin. Genes that determine sweat gland structure and function are largely unidentified. Here we report that a Fox family transcription factor, Foxc1, is obligate for appreciable sweat duct activity in mice. When Foxc1 was specifically ablated in skin, sweat glands appeared mature, but the mice were severely hypohidrotic. Morphological analysis revealed that sweat ducts were blocked by hyperkeratotic or parakeratotic plugs. Consequently, lumens in ducts and secretory portions were dilated, and blisters and papules formed on the skin surface in the knockout mice. The phenotype was strikingly similar to the human sweat retention disorder miliaria. We further show that Foxc1 deficiency ectopically induces the expression of keratinocyte terminal differentiation markers in the duct luminal cells, which most likely contribute to keratotic plug formation. Among those differentiation markers, we show that Sprr2a transcription is directly repressed by over-expressed Foxc1 in keratinocytes. In summary, Foxc1 regulates sweat duct luminal cell differentiation, and mutant mice mimic miliaria and provide a possible animal model for its study.

Keywords: sweat gland, miliaria, hypohidrosis, hyperhidrosis, Foxa1

Introduction

Sweat glands comprise a tiny but dynamically potent secretory organ. In humans, the millions of sweat glands are spread over the entire body and are capable of secreting up to liters of sweat per hour (Sato et al., 1989). Evaporation of large amount of sweat from skin surface effectively dissipates body heat, making long-distance running possible. And anhidrotic/hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia patients, who lack sweat glands, have anecdotally been found to be at relative risk of high fever and death (Blüschke et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 1987).

In both rodents and humans, each sweat gland tubule has a coiled secretory portion and a relatively straight duct region leading to the skin surface. Isotonic primary sweat secretion by cells in the secretory portion involves the function of specific transcription factors, ion channels, pumps and cotransporters (Cui and Schlessinger, 2015; Cui et al., 2016). Ions in primary sweat are then partially reabsorbed along the sweat ducts, resulting in hypotonic final sweat. Thus, sweat secretion is a coordinated process of the secretory portion and the reabsorptive duct (Sato et al., 1989). However, the mechanisms for sweat secretion and structural maintenance of the glands are still largely unknown.

Unlike in humans, sweat glands are restricted to the ventral paw skin in rodents. Their delimited location in mice facilitates specific study of sweat gland function and homeostasis. Mutations in secretory or duct cells have been shown to result in defective sweat secretion. Deficiencies in Foxa1 transcription factor (Cui et al., 2012) or in a calcium channel InsP3R2 in mice or patients (Klar et al., 2014) show severe hypohidrosis. In addition, mutations in CFTR are well known to cause the life threatening disease, cystic fibrosis, which affects reabsorption of salt by sweat ducts (Quinton, 2007). We have previously reported that Foxa1/Best2 regulate sweat secretion in the secretory portion (Cui et al., 2012), and now find that another Fox family member, Foxc1, is required for sweat duct homeostasis. By generating skin specific Foxc1 knockout mice, we show that Foxc1 ablation results in severe hypohidrosis due to sweat duct blockage, resembling the common human sweat retention disorder miliaria.

Results

Foxc1 has been associated with the development of anterior segments of the eye: and mutations lead to Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome type 3 (OMIM602482). Foxc1 also controls vascular growth in the cornea and outgrowth and branching of lacrimal glands (Mattiske et al., 2006; Seo et al., 2012). Extraocular features have also been reported in Foxc1 mutant patients (Kume, 2009), and two recent studies published during submission of this manuscript showed that Foxc1 regulates hair follicle stem cell quiescence (Lay et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). We had earlier noted that Foxc1 was highly expressed in mouse sweat glands (Kunisada et al., 2009), but no corresponding function had been determined.

Skin specific Foxc1 knockout mice show severe hypohidrosis

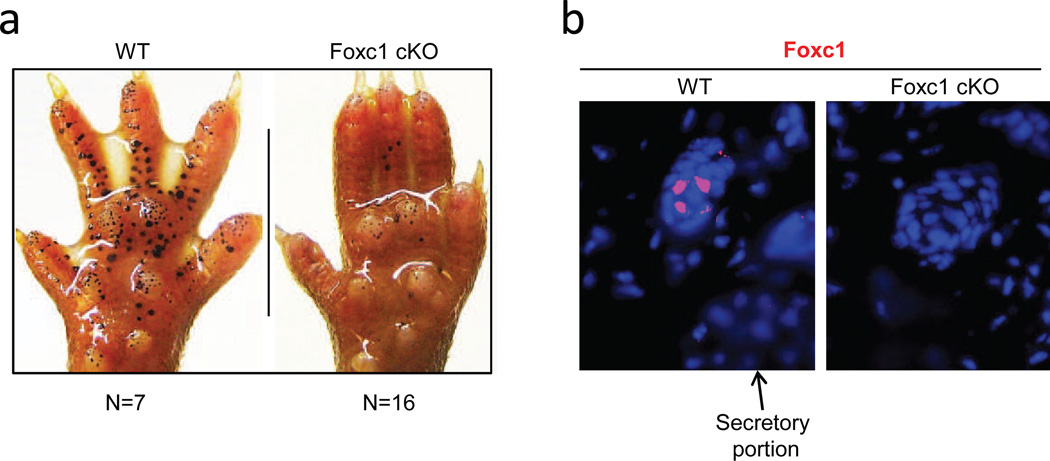

To analyze Foxc1 function in sweat glands, we generated skin specific Foxc1 knockout mice (Foxc1 cKO) by crossing Foxc1loxP/loxP mice (Sasman et al., 2012) with K14-cre mice (Fig. S1a, b). The resultant homozygous adult Foxc1 cKO mice showed no discernible gross defects. However, the cKO mice failed to sweat, with phenotypes range from severe to complete anhidrosis (Fig. 1a shows an instance of severe hypohidrosis). In immunostaining, Foxc1 protein was observed in wild-type mice throughout the dermal sweat duct, but not in epidermal sweat duct or the secretory coil (Fig. 1b). We further analyzed cell layers of sweat ducts. Basal duct cells have been shown to promote sweat reabsorption. By contrast, the function of luminal duct cells are unknown (Sato et al., 1989), but they proved to be the site of expression of Foxc1 in wild-type sweat glands, localized in cell nuclei (Fig. 1b, broken circles). The figure also shows Foxc1 expression barely above background in basal duct cells (arrows); and as expected, no expression in cKO sweat glands.

Fig. 1.

Skin specific Foxc1 cKO mice are hypohidrotic. a, Iodine-starch sweat test. Black dots represent sweating spots. Foxc1 cKO mice show severe hypohidrosis compared to wild-type littermate. b, Localization of Foxc1 in sweat glands. Foxc1 positive cells (red) are located exclusively in nuclei of luminal duct cells (broken circles), but not in basal duct cells (arrows) or secretory portion. Foxc1 cKO mice are devoid of signal. Blue, DAPI staining. Scale bar = 15µm.

Sweat glands were fully formed without Foxc1, but sweat ducts were blocked by keratotic plugs

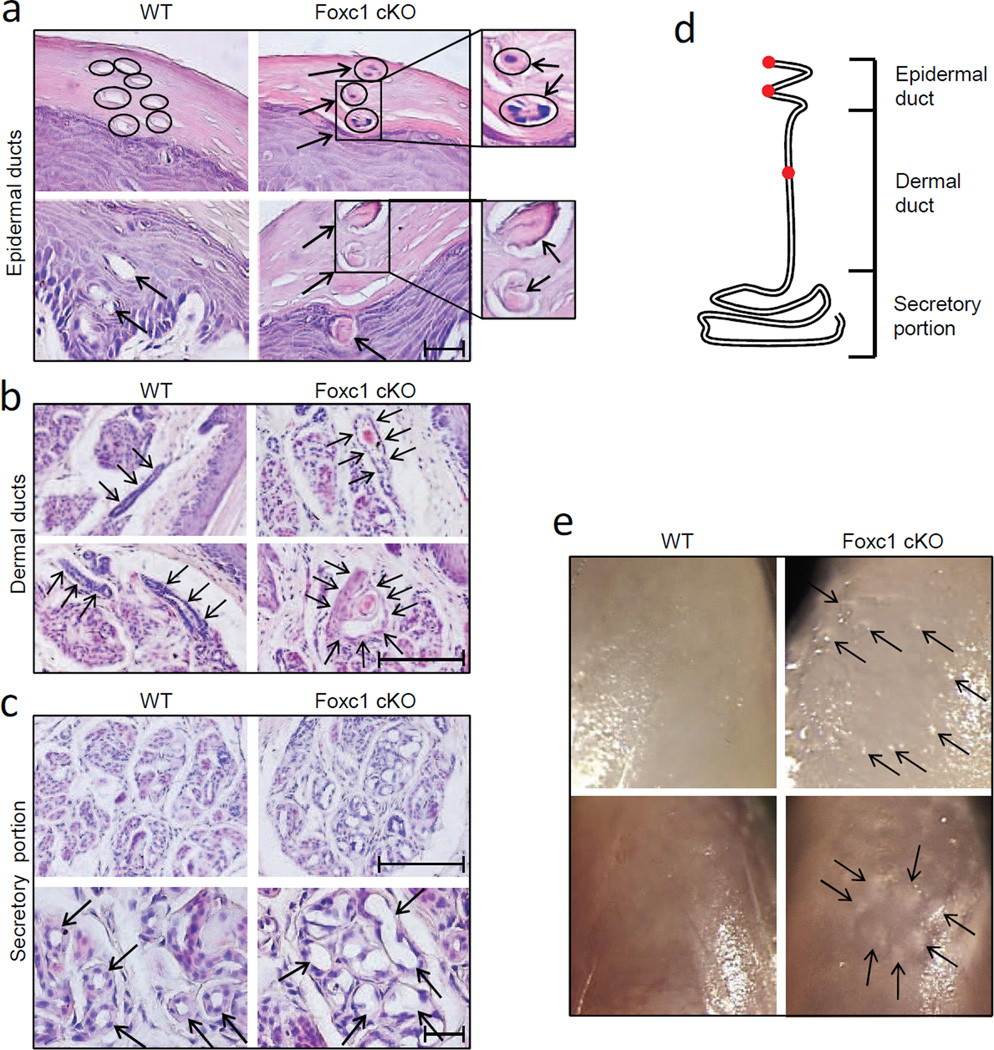

Correlated with Foxc1 localization, striking pathological changes were seen in sweat ducts in adult cKO mice. Histological analysis showed that sweat glands were apparently fully formed in the cKO mice, but the sweat ducts were stuffed with keratotic plugs (Fig. 2a–c). As schematized in Fig. 2d, a sweat duct can be divided into a helical epidermal and a relatively straight dermal duct. Epidermal sweat ducts were blocked by either parakeratotic plugs (Fig. 2a, upper right panel) or hyperkeratotic plugs (Fig. 2a, lower right panel) at the level of the surface stratum corneum or the inner layer of the stratum Malpighi. Dermal sweat ducts were comparably blocked by hyperkeratotic plugs in upper (Fig. 2b, upper right panel) and lower (Fig. 2b, lower right panel) portions of the ducts, and duct lumens were noticeably dilated in the cKO mice (Fig. 2b, arrows in right panels point to dilated dermal sweat ducts). In addition, dermal luminal duct cells were often disarrayed and even detached in some cases in the cKO mice (Figs. 2b, S4b). In wild-type mice, by contrast, both epidermal and dermal duct lumens were open (Fig. 2a, b, left panels). Similar to duct lumens, but different from wild-type controls, the secretory lumens in the cKO secretory portion were also significantly dilated (Fig. 2c, upper panels). Furthermore, the secretory cells surrounding dilated lumens in the cKO mice, usually cuboidal or columnar in wild-type mice, were flattened (Fig. 2c, arrows in magnified lower panels), consistent with compression by confined, increasing amounts of sweat. Further supporting sweat retention associated with duct blockage, we consistently saw small blisters and papules formed on ventral skin of the cKO digit tips (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Morphological analyses of Foxc1 cKO sweat glands. a, Epidermal sweat ducts were blocked by parakeratotic plugs (upper right panel; cell nuclei can be spotted in the plugs) or hyperkeratotic plugs (lower right panel). Small panels at right show higher magnifications. Epidermal sweat ducts were empty in wild-type controls (left panels). b, Dermal sweat ducts were blocked by hyperkeratotic plugs in upper (upper right panel) and lower (lower right panel) portions. Note: compared to wild-type controls (left panels), dermal ducts in Foxc1 cKO mice were significantly dilated (surrounded by arrows). c, Lumens in secretory portion were also significantly dilated in Foxc1 cKO mice (upper right panel, compared to upper left). Further, secretory cells surrounding dilated secretory lumens were flattened in the cKO mice (arrows in lower right panel, compared to lower left panel). d, Illustration of a sweat gland. Sweat glands consist of a short helical epidermal duct, a relatively straight dermal duct, and a coiled secretory portion. Sweat duct blockage in Foxc1 cKO mice was found in the epidermal duct in stratum corneum, lower epidermis, and in deeper dermal duct (red dots). e, Small blisters (upper right panel) and papules (lower right panel) were formed in digit tips of Foxc1 cKO mice, but not in wild-type controls. Scale bars = 50µm.

The duct blockage and hypohidrosis in Foxc1 cKO mice were quite similar to features of a common sweat retention disorder miliaria in humans (see Discussion), but direct observations on patients are required to investigate the degree of similarity of mouse and human conditions.

Expression of sweat gland markers indicated abnormal sweat duct differentiation in Foxc1 cKO mice

To analyze gene expression changes associated with pathology in the knockout mice, we examined the levels of several sweat gland markers by immunostaining, and found that most of them were normally expressed in the cKO mice. We first studied Krt14 as a epidermal basal cell, basal duct cell and myoepithelial cell marker, and Krt8 as a secretory cell marker (Cui and Schlessinger, 2015). In both wild-type and cKO mice, Krt14 was expressed in the basal layer of epidermis, in basal cells of epidermal and dermal sweat ducts, and in myoepthelial cells of the secretory portion (Fig. S2a, b). Notably, dermal sweat ducts in the cKO mice had an irregular shape, consistent with observations in H&E staining (Fig. S2a compared to Fig. 2b and Fig. S4b). Krt8 was also strongly expressed in secretory cells of cKO mice, as in wild-type controls (Fig. S2b).

The expression patterns of Foxa1, regulating sweat secretion; Nkcc1, the major player in the NKCC cotransporter model; and p63, a master regulator of keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation (Botchkarev and Flores, 2014; Cui and Schlessinger, 2015) were also analyzed for expression patterns and found to be unchanged in the cKO mice (Fig. S2c, d). In both wild-type and Foxc1 cKO mice, Foxa1 was expressed in the nuclei of scattered secretory cells, and Nkcc1 was localized on basolateral membranes of the secretory cells (Fig. S2c). p63, which we found specifically expressed in the nuclei of basal keratinocytes, basal sweat duct cells, and the sweat gland stem cell niche myoepithelial cells, again showed no significant differences between wild-type and cKO mice (Fig. S2d).

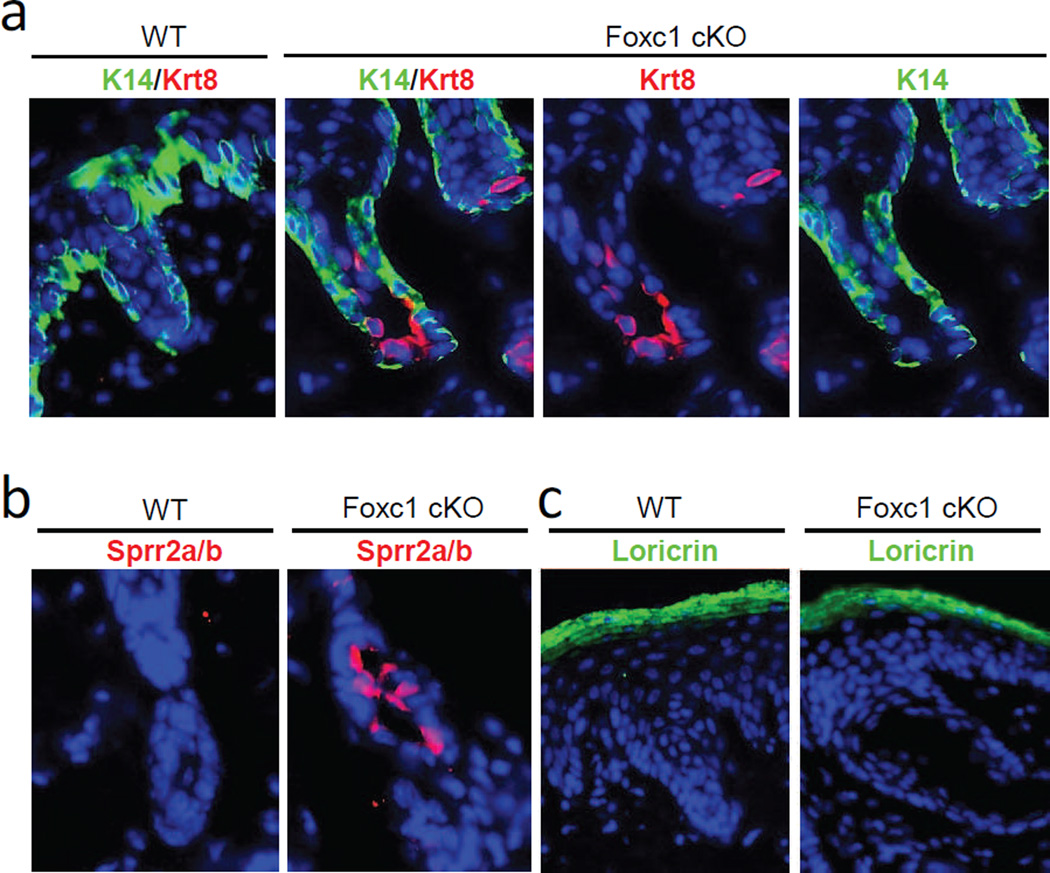

A striking abnormality was, however, evident in the sweat duct. Krt8, which was absent in wild-type sweat ducts (Fig. 3a), was instead intensely expressed in the dermal sweat duct in the cKO mice, specifically in the luminal (and not in basal) cells. Thus, consistent with histological findings, sweat duct differentiation -- rather than the secretory machinery -- seemed to be aberrant in Foxc1 cKO mice.

Fig. 3.

Ectopic expression of differentiation markers in sweat duct luminal cells in Foxc1 cKO mice. a, Krt8 (red) was highly expressed in luminal cells of sweat ducts in Foxc1 cKO mice, but not in wild-type controls. Krt14 (green) was expressed in basal duct cells in both wild-type and Foxc1 cKO mice. b, Sprr2 (a+b) (red) were intensely expressed in luminal duct cells in Foxc1 cKO mice (arrows), but were absent in wild-type sweat ducts. c, Loricrin (green) was strongly expressed in granular and upper spinal layers of skin epidermis, but absent in sweat glands of both wild-type and Foxc1 cKO mice. Blue, DAPI staining. Scale bars = 20µm.

Foxc1 ablation induced ectopic expression of genes required for keratinocyte terminal differentiation in sweat duct luminal cells

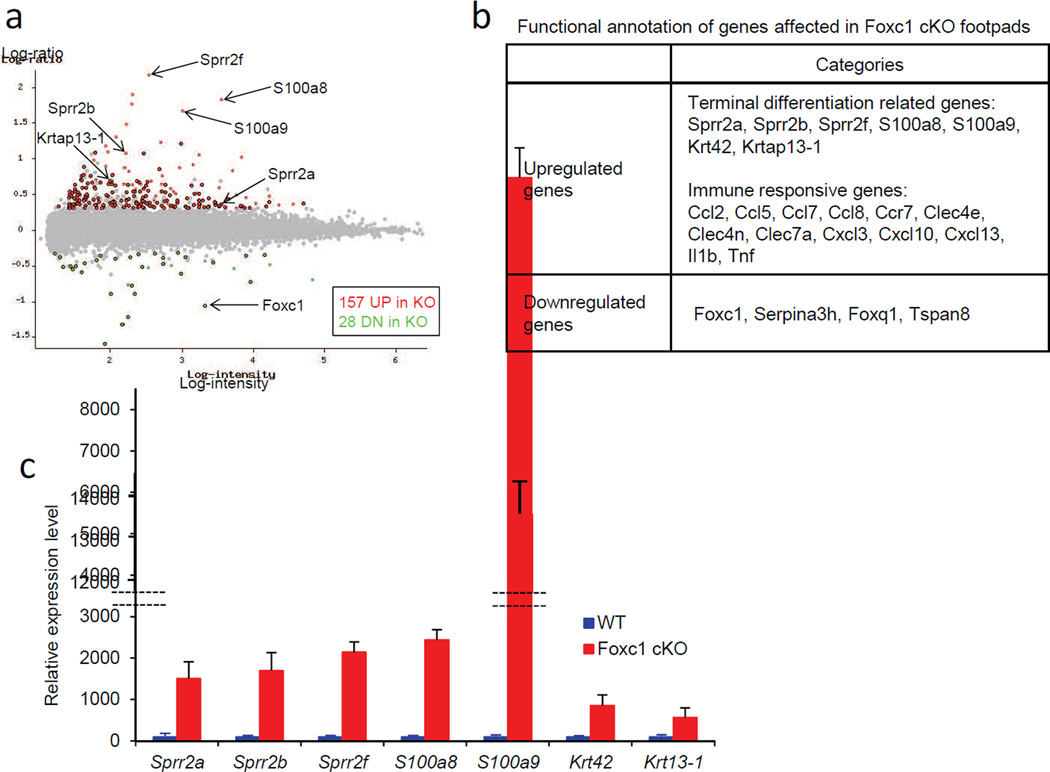

A more comprehensive list of genes affected in sweat glands by Foxc1 ablation was assessed by genome-wide expression profiling of wild-type and cKO mice at postnatal day 59 (see Materials and Methods). Twenty- eight genes – including Foxc1 – were significantly downregulated, and a much larger group of 157 genes, 83% of the total, were significantly upregulated in the cKO mice (determined as showing greater than 2-fold change in expression level at FDR<0.05; the full list is in Supplementary Table S1) (Fig. 4a). By functional annotation, we found sharp upregulation of several markers of terminal differentiation of keratinocytes (Candi et al., 2005), including Sprr2a, Sprr2b, Sprr2f, S100a8, S100a9, Krt42 and Krtap13-1 in the cKO mice (Fig. 4b). We used qRT-PCR to validate changes in these genes, and confirmed significant upregulation, ranging from 5-fold (Krtap13-1) to 135-fold (S100a9), in the cKO mice (Fig. 4c). Additionally, by immunostaining we further analyzed Sprr2a/2b, and found these proteins to be highly expressed in the luminal cells of dermal sweat ducts in the cKO mice, but absent in wild-type controls (Fig. 3b). Sprr proteins complex with loricrin, the major component of the cornified cell envelope in terminally differentiating keratinocytes in skin epidermis (Candi et al., 2005). However, the level of loricrin mRNA was not changed in the expression profile of cKO mice, and immunostaining further showed that loricrin was highly expressed in the granular layer of skin epidermis in both wild-type and cKO mice, but was totally absent in the ducts and secretory portions of sweat glands (Fig 3c). Thus, their protein partner was not present in the same cells as Sprr proteins, suggesting that altered sweat duct luminal cells in the cKO mice most likely do not form cornified cell envelopes.

Fig. 4.

Expression profiling revealed upregulation of a set of terminal differentiation markers in Foxc1 cKO sweat glands. a, A scatter plot shows up or down regulated genes in Foxc1 cKO sweat glands. Total of 185 genes were significantly affected in Foxc1 cKO mice [157 genes up (red), and 28 genes down (green)]. In Foxc1 cKO mice, terminal differentiation markers, including Sprr2a, Sprr2b, Sprr2f, S100a8, S100a9, Krt42 and Krtap13-1, were significantly upregulated, and Foxc1 was sharply downregulated. b, Functional annotation revealed upregulation of terminal differentiation markers and immune responsive genes in Foxc1 cKO mice. c, qRT-PCR assays confirmed significant upregulation of terminal differentiation markers in Foxc1 cKO sweat glands.

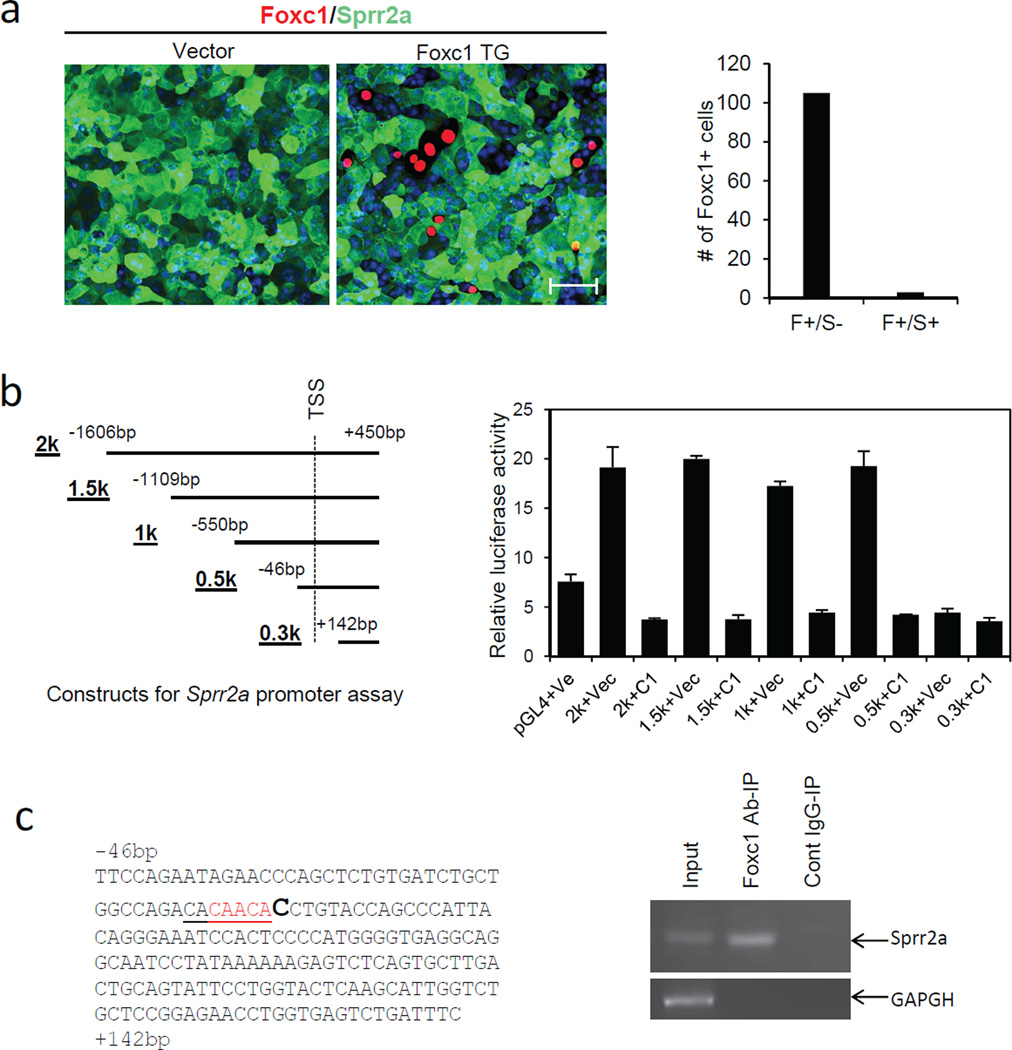

Foxc1 downregulates Sprr2a transcription

We next asked how Foxc1 might regulate terminal differentiation markers. By immunostaining and qRT-PCR assays, we found that 308 mouse keratinocytes (Yuspa et al., 1983) highly express Sprr2a (Fig. 5a and Fig. S3) (Sprr2b and loricrin were expressed little if at all). Unlike wild-type keratinocytes, 308 keratinocytes are known to be resistant to Ca2+ induced terminal differentiation (Hennings et al., 1987), and as expected added Ca2+ did not affect Sprr2a expression (Fig. S3). To assess a possible repressive action of Foxc1 on Sprr2a, we transfected 308 keratinocytes with Foxc1-expressing plasmid. Co-immunostaining showed that Sprr2a was positive in most keratinocytes, but was negative in essentially all Foxc1 transfected cells (Fig. 5a, Right). Thus, over-expressed Foxc1 suppresses Sprr2a expression in keratinocytes, consistent with upregulation of Sprr2a in Foxc1 cKO mice.

Fig. 5.

Foxc1 represses Sprr2a expression in keratinocytes. a, Immunostaining shows that the 308 mouse keratinocytes highly express Sprr2a (green). Cells transfected with Foxc1 (red) lack Sprr2a expression. Scale bar = 25µm. Right panel, all most all counted Foxc1-positive cells are Sprr2anegative (F+/S−). B, Left panel shows Sprr2a constructs for Luciferase assay. Right panel, Foxc1 represses promoter activity of Sprr2a, and the 0.5K-0.3K fragment is responsible for the repression. C, Left, shows the sequence of the 0.5K-0.3K fragment. Red indicates a partial Fox binding site. Right, ChIP assay shows that Foxc1 binds to the 0.5K-0.3K fragment.

With the same cells we further analyzed whether the Sprr2a promoter region is directly regulated by Foxc1. We cloned 2kb, 1.5kb, 1kb, 0.5kb and 0.3kb DNA fragments from the −1.6kb ~ +0.45kb region of the Sprr2a transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 5b, left), and screened Foxc1 action on them by its effect on the expression of distal luciferase. Luciferase activity was significantly elevated in the cells transfected with 2kb, 1.5kb, 1kb and 0.5kb fragments, but not with 0.3kb fragment (Fig. 5b, right). Notably, co-transfection with a plasmid expressing Foxc1 showed sharp downregulation of luciferase activity for all the fragments that increased activity in its absence (Fig. 5b, right).

These results confirmed inhibitory action of Foxc1 on Sprr2a, and further indicated that Foxc1 interacts with Sprr2a in the −46bp ~ +142bp promoter region (Fig. 5b, left). We found no typical Foxc1 binding sites in this region (Berry et al., 2008; Saleem et al., 2003), but a partial Fox binding motif, CAACA (five out of seven nucleotides) was found just 5’ to the transcription start site (Fig. 5c, left). Five nucleotide matching was previously shown to be sufficient to interact with Foxc1 (Sun et al., 2013), and we further carried out Chromatin-IP (ChIP). PCR amplification with the transcription start site primers (See Supplementary Materials and Methods) from chromatin immunoprecipitated by Foxc1 antibody, yielded a corresponding product band that was absent from chromatin precipitated by control IgG (Fig. 5c, right). As expected, GAPDH was negative for both precipitated chromatin fractions (Fig. 5c, right). Collectively, these results indicated that Foxc1 represses Sprr2a transcription by direct interaction with Sprr2a promoter region.

Inflammatory genes were upregulated secondarily in adult Foxc1 cKO sweat glands

The group of genes significantly upregulated in adult cKO mice also included numerous immune and inflammation-related genes (Fig. 4b, and Table S1). We hypothesized that this upregulation could be secondary to sweat duct pathology, most likely provoked by sweat leakage after duct blockage in the absence of Foxc1. If so, younger mice might leak less and the expression change of inflammatory genes would be far less. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed 20-day old mice at when sweat glands were just mature structurally and functionally (Tafari et al., 1997), and compared them with 2-month old adult mice. As in adult mice, sweat tests showed severe hypohidrosis in the younger cKO mice (Fig, S4a). Epidermal sweat duct blockage and dermal sweat duct dilation were already evident (Fig. S4b), and immunostaining showed positive signals for Sprr2a/2b in the luminal cells of dermal sweat duct (Fig. S4c). But secretory cell flattening was apparently milder in younger cKO mice (Fig. S4b), and qRT-PCR assays showed that upregulated cytokines in adult cKO mice, including Ccl5, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Il19 and Tnf, were not yet significantly altered (Fig. S4d). From these results we infer that upregulation of inflammatory genes in adult cKO mice is secondary to sweat duct blockage and sweat leakage.

Discussion

Like FoxA1, Foxc1 is another Fox family transcription factor involved in sweat dynamics. Foxc1 is exclusively expressed in the luminal cells of the sweat duct, and its ablation causes a severe defect in luminal cell differentiation, resulting in keratotic plug formation and severe hypohidrosis. The dilation of lumens and the flattening of secretory cells in Foxc1 cKO mice, most likely by sweat retention, indicate that secretory cells may retain normal function. The phenotypes seen in Foxc1 cKO mice are strikingly similar to a common human sweat retention disorder, miliaria (Arpey et al., 1992). As in Foxc1 cKO mice, hypohidrosis in miliaria is similarly caused by epidermal or dermal sweat duct blockage by hyperkeratotic or parakeratotic plugs, and not by dysfunction of secretory cells (Arpey et al., 1992; Kirk et al., 1996; Tey et al., 2015). Depending on the blockage site, miliaria can be divided into 3 subtypes, miliaria crystallina, miliaria rubra, and miliaria profunda (Arpey et al., 1992; Kirk et al., 1996). The blockage sites of Foxc1 cKO mice include those of all 3 miliaria subtypes -- i.e., ducts in stratum corneum, lower epidermis, and dermis (Fig. 2d).

The pathophysiology of miliaria is poorly understood. Causative keratotic plug formation in miliaria was suggested to result from a repair process by duct luminal cells after sweat duct injury by UV damage or bacterial infection (Arpey et al., 1992; Shuster, 1997). Our findings of ectopic expression of terminal differentiation markers in the duct luminal cells in Foxc1 cKO mice suggest that rather than injury, altered intrinsic differentiation can be a causative factor. The altered differentiation status of Foxc1 cKO duct luminal cells, however, was different from the standard epidermal keratinocyte differentiation program, because the partner of Sprrs, loricrin, was not expressed in the luminal cells. Additional expression of Krtap13-1, Krt42 and Krt8 further suggested additional complexity in keratotic plug formation in the cKO sweat ducts. Krtap13-1 forms terminally differentiated hair shafts with hair keratins (Rogers et al., 2002), and Krt42 is known as a nail keratin (Cui et al., 2013; Tong and Coulombe, 2004). By contrast, Krt8 is expressed only in secretory cells of sweat glands in adult mice; and over-expression of Krt8 and its partner Krt18 was shown to promote the abnormal invasion of squamous cell carcinoma (Yamashiro et al., 2010). Thus, genes that can drive cells into distinct differentiation directions are concomitantly activated in the sweat duct luminal cells in the absence of Foxc1, and likely contribute to abnormal terminal differentiation.

Foxc1 was shown to be a transcriptional activator in most published cases (Lay et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016), and thus our finding of repressive action on sweat duct luminal cell differentiation implied a surprisingly different mechanism. Therefore, we further analyzed whether Foxc1 represses those differentiation markers in a keratinocyte culture system. Sprr2a, one of the upregulated differentiation markers in the cKO sweat glands, was highly expressed in the 308 mouse keratinocyte line (Hennings et al., 1987; Yuspa et al., 1983), and we thus carried out further analyses with those cells. Consistent with in vivo observations, in vitro transfection experiments, luciferase assays and ChIP analyses showed that Foxc1 represses Sprr2a transcription by direct interaction with its promoter region. Also consistent with a repressive action, transcriptional silencing mutations of Foxc1 have been identified in massively growing endometrial and ovarian primary cancers (Zhou et al., 2002). A further hint of a repressive role of Foxc1 comes from the strikingly greater number of upregulated genes in cKO sweat glands compared to downregulated genes in expression profiling (157 up, 28 down). Downstream effectors of Foxc1 in sweat glands were also much different from those seen in hair follicle stem cells. In particular, Nfatc1 or Bmp2/6, the major targets of Foxc1 in hair follicles are not significantly affected in sweat glands, and the observed altered expression of differentiation markers was not seen in hair follicle stem cells (Lay et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Thus, our findings suggest that depending on cellular context, Foxc1 may activate or repress expression of downstream effectors for development, homeostasis and tumorigenic conditions. A similar versatility has been seen for p63, a master regulator of keratinocytes (Botchkarev and Flores, 2014). The mechanism regulating Foxc1 expression, however, remains unknown. Epigenetic regulation and DNA methylation in particular may be important for cell specific expression or silencing of Foxc1 (Botchkarev et al., 2012). We observed the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 is expressed in sweat duct and secretory cells (Fig. S5), and it remains to be seen if it is involved in Foxc1 regulation.

In summary, Foxc1 knockout mice establish this transcription factor as critical in sweat glands, and the knockout model may help to replicate miliaria pathogenesis. At present, it is not known whether any cases of human miliaria result directly from defects in Foxc1, but analysis of expression patterns of Foxc1 and associated genes in sweat glands of patients may aid in molecular diagnosis; the mouse model could provide a tool for the screening of therapeutic approaches for miliaria.

Materials and methods

Animal models and sweat test

All animal study protocols were approved by the NIA Institutional Review Board (Animal Care and Use Committee). Skin specific Foxc1 cKO mice were generated by crossing Foxc1loxP/loxP mice (Sasman et al., 2012) with K14-Cre mice (Fig. S1a). Genotyping was done by PCR (Fig. S1b). Sweat test was done with WT and Foxc1 cKO mice as reported (Cui et al., 2012).

Histology and immunefluorescence staining

Ventral paw skin was taken out from wild-type and Foxc1 cKO mice 20-day or 59-day after birth, fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were deparaffinized, and H&E staining or immunostaining was performed on sections.

Sample collection, RNA isolation, expression profiling and qRT-PCR assays

For expression profiling of Foxc1 cKO sweat glands, dome shaped footpads were dissected from ventral paw skin from Foxc1 cKO and littermate WT mice at postnatal day 59. Four mice for each genotype, yielding 4 biological replicates for expression profiling.

Total RNA were isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen), reprecipitated by LiCl (Ambion), and expression profiling was done with the NIA Mouse 44K Microarray (Agilent Technologies). Data were analyzed by ANOVA. Genes with FDR<0.05, fold-difference>2.0, and mean log intensity>2.0 were considered to be significant. Hybridization data were deposited in the GEO (GSE77143).

One-step TaqMan qRT-PCR was carried out with ready-to-use probe/primer sets (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were normalized to GAPDH, and data were analyzed by Student’s t-test.

Immunocytochemistry, Luciferase and ChIP assays

For Immunocytochemistry, mouse 308 keratinocytes were transfected with pCMV-Foxc1 plasmid (OriGene), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (MP Biomedicals), treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and stained with Sprr2a/2b and Foxc1 antibodies.

For Luciferase assays, 2kb, 1.5kb, 1kb, 0.5kb and 0.3kb DNA fragments were amplified from the −1.6kb to +0.45kb region of the Sprr2a transcription start site (TSS) by PCR, cloned into the pGL4.14-Basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and verified by sequencing. 308 mouse keratinocytes in 24-well plates were co-transfected with Sprr2a-Firefly plasmid, Renilla reporter vector (Promega), and pCMV-Foxc1 plasmid using FuGENE HD reagent (Promega), and luciferase assay was done with Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) 48–72h later. Each experiment was triplicated and all experiments were repeated three times.

ChIP analysis was performed using a ChIP kit (abcam). Foxc1 transfected 308 cells were fixed with formaldehyde and lysed. Chromatin was sheered by sonication, diluted and was incubated with goat anti-Foxc1 (abcam) or 5µg non-specific goat IgG (abcam). Antibody-bound chromatin was isolated using Protein G Sepharose beads (abcam), purified, and was analyzed with endpoint PCR with primers covering the −46bp~+142bp promoter region of Sprr2a. GAPDH was used as an input control.

Detailed information can be found in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

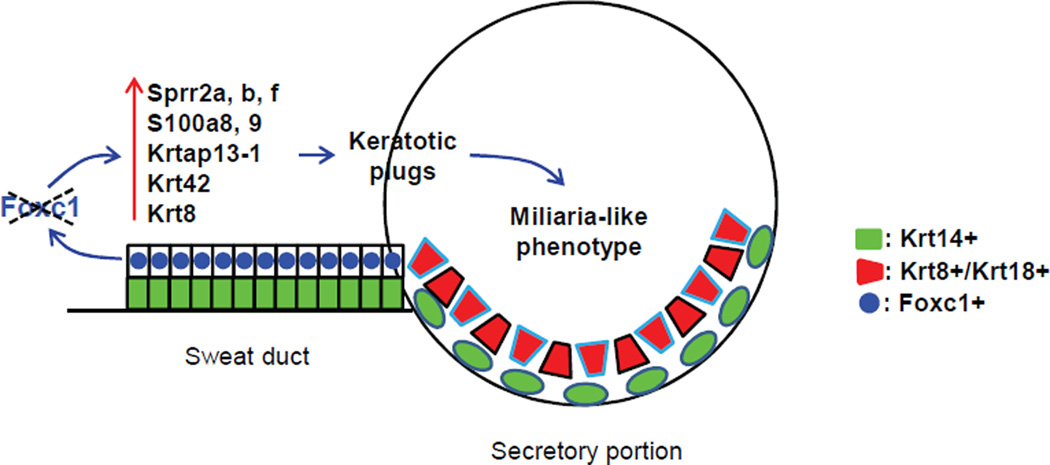

Fig. 6.

A schematic representation of Foxc1 action in sweat glands. Foxc1 is expressed in sweat duct luminal cells, and its ablation causes ectopic expression of terminal differentiation markers including Sprr proteins, S100a proteins, and several keratin and keratin associated proteins, resulting in hyperkeratotic or parakeratotic plug formation in sweat duct. A miliaria-like phenotype is caused by sweat duct blockage by keratotic plugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (EY019484 and HL126920) to TK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Arpey CJ, Nagashima-Whalen LS, Chren MM, Zaim MT. Congenital miliaria crystallina: case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 1992;9:283–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1992.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry FB, Skarie JM, Mirzayans F, Fortin Y, Hudson TJ, Raymond V, et al. FOXC1 is required for cell viability and resistance to oxidative stress in the eye through the transcriptional regulation of FOXO1A. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:490–505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüschke G, Nüsken KD, Schneider H. Prevalence and prevention of severe complications of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:397–399. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Flores ER. p53/p63/p73 in the epidermis in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015248. pii:a015248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Gdula MR, Mardaryev AN, Sharov AA, Fessing MY. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2505–2521. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Phillips DI, Brown R, Harper PS. Clinical aspects of X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:989–996. doi: 10.1136/adc.62.10.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui CY, Childress V, Piao Y, Michel M, Johnson AA, Kunisada M, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FoxA1 regulates sweat secretion through Bestrophin 2 anion channel and Na-K-Cl cotransporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1199–1203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117213109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui CY, Klar J, Georgii-Heming P, Fröjmark AS, Baig SM, Schlessinger D, et al. Frizzled6 deficiency disrupts the differentiation process of nail development. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1990–1997. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui CY, Schlessinger D. Eccrine sweat gland development and sweat secretion. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:644–650. doi: 10.1111/exd.12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui CY, Sima J, Yin M, Michel M, Kunisada M, Schlessinger D. Identification of potassium and chloride channels in eccrine sweat glands. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;81:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennings H, Michael D, Lichti U, Yuspa SH. Response of carcinogen-altered mouse epidermal cells to phorbol ester tumor promoters and calcium. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:60–65. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12465014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk JF, Wilson BB, Chun W, Cooper PH. Miliaria profunda. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:854–856. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar J, Hisatsune C, Baig SM, Tariq M, Johansson AC, Rasool M, et al. Abolished InsP3R2 function inhibits sweat secretion in both humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4773–4780. doi: 10.1172/JCI70720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T. The cooperative roles of Foxc1 and Foxc2 in cardiovascular development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;665:63–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1599-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisada M, Cui CY, Piao Y, Ko MS, Schlessinger D. Requirement for Shh and Fox family genes at different stages in sweat gland development. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1769–1778. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay K, Kume T, Fuchs E. FOXC1 maintains the hair follicle stem cell niche and governs stem cell quiescence to preserve long-term tissue-regenerating potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1506–E1515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601569113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiske D, Sommer P, Kidson SH, Hogan BL. The role of the forkhead transcription factor, Foxc1, in the development of the mouse lacrimal gland. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1074–1080. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton PM. Cystic fibrosis: lessons from the sweat gland. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:212–225. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Langbein L, Winter H, Ehmann C, Praetzel S, Schweizer J. Characterization of a first domain of human high glycine-tyrosine and high sulfur keratin-associated protein (KAP) genes on chromosome 21q22.1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48993–49002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem RA, Banerjee-Basu S, Berry FB, Baxevanis AD, Walter MA. Structural and functional analyses of disease-causing missense mutations in the forkhead domain of FOXC1. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2993–3005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasman A, Nassano-Miller C, Shim KS, Koo HY, Liu T, Schultz KM, et al. Generation of conditional alleles for Foxc1 and Foxc2 in mice. Genesis. 2012;50:766–774. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, Sato KT. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders. I. Normal sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:537–563. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S, Singh HP, Lacal PM, Sasman A, Fatima A, Liu T, et al. Forkhead box transcription factor FoxC1 preserves corneal transparency by regulating vascular growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2015–2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109540109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster S. Duct disruption, a new explanation of miliaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:1–3. doi: 10.2340/0001555577001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Ishii M, Ting MC, Maxson R. Foxc1 controls the growth of the murine frontal bone rudiment by direct regulation of a Bmp response threshold of Msx2. Development. 2013;140:1034–1044. doi: 10.1242/dev.085225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafari AT, Thomas SA, Palmiter RD. Norepinephrine facilitates the development of the murine sweat response but is not essential. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4275–4281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04275.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tey HL, Tay EY, Cao T. In vivo imaging of miliaria profunda using high-definition optical coherence tomography: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:346–348. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Coulombe PA. A novel mouse type I intermediate filament gene, keratin 17n (K17n), exhibits preferred expression in nail tissue. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:965–970. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Siegenthaler JA, Dowell RD, Yi R. Foxc1 reinforces quiescence in self-renewing hair follicle stem cells. Science. 2016;351:613–617. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro Y, Takei K, Umikawa M, Asato T, Oshiro M, Uechi Y, et al. Ectopic coexpression of keratin 8 and 18 promotes invasion of transformed keratinocytes and is induced in patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa SH, Kulesz-Martin M, Ben T, Hennings H. Transformation of epidermal cells in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81:162s–168s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Kato H, Asanoma K, Kondo H, Arima T, Kato K, et al. Identification of FOXC1 as a TGF-beta1 responsive gene and its involvement in negative regulation of cell growth. Genomics. 2002;80:465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.