Abstract

Mycobacterium kansasii is the second most common cause of slowly growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria diseases in China. The aim of the present study was to analyze M. kansasii subtypes isolated from patients in China, and to explore the antimicrobial susceptibility of the differentiation among these diverse subtypes. A total of 78 M. kansasii strains from 16 provinces of China were enrolled in this study. Amikacin (AMK) was the most highly active against M. kansasii strains, and only 4 isolates (5.1%) exhibited in vitro resistance to AMK. The percentage of levofloxacin (LFX) resistant strains among the 78 M. kansasii isolates was 39.7% (31/78), which was significantly higher than that of moxifloxacin (16.7%, P = 0.001) and gatifloxacin (19.2%, P = 0.005). By using PCR-restriction fragment analysis of the hsp65 gene (PRA), all the isolates were classified as four different subtypes. Of these four subtypes, M. kansasii subtype I was the most frequent genotype in China, accounting for 71.8% (56/78) of M. kansasii isolates. Resistance to clarithromycin (CLA) was noted in 26.8% (15/56) of subtype I isolates, which was significant higher than that of other subtypes (4.5%, P = 0.031). DNA sequencing revealed that the presence of mutations in 23S rRNA was associated with 56.2% (9/16) of CLA-resistant M. kansasii isolates. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that AMK is the most active agent against M. kansasii in vitro, while the high proportion of CLA resistance is noted in M. kansasii isolates. In addition, the predominant subtype I is associated with CLA resistance in China.

Keywords: Mycobacterium kansasii, clarithromycin, subtype, drug susceptibility, China

Introduction

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are a large, diverse group of environment organisms that are ubiquitous in the soil, water, animals, human, and food (Griffith et al., 2007; Prevots and Marras, 2015). Despite of low pathogenicity to humans, NTM can cause a wide array of clinical illness, especially in human immune-deficiency virus (HIV) infected patients or those with severely compromised immune systems (Prevots and Marras, 2015). In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to disease caused by NTM because of its more prevalent incidence globally (Hoefsloot et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2014).

Only behind Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium kansasii is the second most common cause of NTM diseases in South American and some European countries (Hoefsloot et al., 2013). In addition to the most frequent pulmonary disease, M. kansasii is a contributor to various clinical manifestations, including extrapulmonary and disseminated diseases in patients with immunodeficiencies (Campo and Campo, 1997; Pintado et al., 1999). Previous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that patients with chronic lung disease, previous mycobacterial disease, malignancy, and alcoholism are at high risk for M. kansasii infection (Guay, 1996). M. kansasii is often recovered from tap water, and occasionally from natural water (McSwiggan and Collins, 1974; Steadham, 1980; Taillard et al., 2003). Due to wide exposure to the bacterium, human-to-human transmission of M. kansasii is traditionally thought to be uncommon (Ricketts et al., 2014). However, a recent report from Ricketts et al. (2014) observed the potential transmission of M. kansasii given the ideal circumstances, providing important insights for public health concern regarding M. kansasii.

PCR-restriction fragment analysis of the hsp65 gene (PRA) is a powerful technique of differentiating heterogeneous subtypes of M. kansasii (Telenti et al., 1993; Santin et al., 2004). To date, seven subtypes (I-VII) have been identified based on the PCR-RFLP profiles (Picardeau et al., 1997; Richter et al., 1999; Santin et al., 2004). Of these seven subtypes, subtype I represents the most frequent isolates contributing to human disease (Taillard et al., 2003), and subtype II is likely to be observed in HIV-infected patients, indicating that it may act as an opportunistic agent (Witzig et al., 1995). In contrast, the other five subtypes are generally isolated from environmental samples rather than human specimens (Alcaide et al., 1999). The niche heterogeneity indicates that there may be diverse pathogenicity and biological features among the M. kansasii subtypes (Santin et al., 2004). Considering drug susceptibility is an important indicator for predicting the clinical outcome of patients infected with M. kansasii, it is meaningful to investigate the assumed difference in drug susceptibility profiles of these seven subtypes. Unfortunately, limited data is known regarding this issue. The aim of the present study was to analyze M. kansasii subtypes isolated from patients in China, and to explore the antimicrobial susceptibility of the differentiation among these diverse subtypes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The protocols applied in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Hospital. The M. kansasii isolates obtained from patients were anonymized, processed using strain number only and were not associated with any identifying details.

M. kansasii Isolates

The strains used in this study were collected from national surveillance of drug resistant tuberculosis from 2008 to 2015 (Zhao et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). All the positive mycobacterial cultures were transferred to National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory for species identification. Conventional species identification was performed with the Löwenstein–Jensen (L–J) medium containing paranitrobenzoic acid (PNB) and thiophen-2-carboxylic acid hydrazide (TCH) (Zhang et al., 2015). The isolates identified as NTM by biochemical method were further divided into species level with sequencing of multiple genes, including 16S rRNA, 65-kD heat shock protein (hsp65), RNA polymerase subunit beta (rpoB), and 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence (Zhang et al., 2015). Briefly, the crude genomic DNA was extracted from colonies harvested from L–J medium according to previous report. The 50 μl amplification mixtures were prepared as follow: 25 μl 2× GoldStar MasterMix (CWBio, Beijing, China), 0.2 μM of each primer set and 5 μl of genomic DNA. PCR program was performed for 35 cycles (94°C for 60 s, 60°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 60 s). The amplicons were sent to Tsingke Company (Beijing, China) for sequencing service. DNA sequence analysis was performed by alignment with the homologous sequences of the reference mycobacterial strains using multiple sequence alignments1. A total of 78 M. kansasii isolates confirmed by molecular method were enrolled for further drug susceptibility testing and PRA identification.

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed following the guidelines by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2011. Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) plus 5% OADC (oleic acid- albumin-dextrose-catalase) was used for broth microdilution testing. A total of twenty antimicrobial agents were selected for MIC determination, including isoniazid (INH), streptomycin (STR), clarithromycin (CLA), amikacin (AMK), rifampicin (RIF), rifabutin (RFB), ethambutol (EMB), linezolid (LZD), moxifloxacin (MOX), levofloxacin (LFX), gatifloxacin (GAT), sulfamethoxazole (SUL), azithromycin (AZM), capreomycin (CAP), tigecycline (TGC), meropenem (MER), minocyline (MIN), cefoxitin (CFX), tobramycin (TOB) and clofazimine (CLO). The concentrations tested ranged from 0.0625 to 128 μg/ml. The breakpoints of antimicrobial agents were recommended by the CLSI:CLA, > 16 μg/ml;RFB, > 1 μg/ml;AMK, > 32 μg/ml;EMB, > 4 μg/ml;LZD, > 16 μg/ml; MOX, > 2 μg/mL;RFB, > 2 μg/ml; and SUL, > 32 μg/ml (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI], 2011). In addition, the breakpoint of levofloxacin was referenced from a previous report, defined as >2 μg/ml (Hombach et al., 2013). For gatifloxacin, the temporary breakpoint was set as > 2 μg/ml, which was also used as breakpoint values of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin. The reference M. kansasii strain (ATCC12478) was enrolled in each batch for quality control purpose.

PRA Identification

The PRA identification was performed as previously described (Telenti et al., 1993). The 441-bp fragment of the hsp65 gene was amplified from genomic DNA with primers Tb11 and Tb12. The PCR product was subjected to restriction enzyme analysis with BstE II and Hae III. The restriction fragments were identified by electrophoresis on a 3% of agarose gel. The patterns of PRA were evaluated at the SwissPRAsite2.

DNA Sequencing

The region corresponding to domain V of the 23S ribosomal RNA (23S rRNA) gene was amplified with primer F1 (5′-GCAAGGGTGAAGCGGAGAA-3′) and primer R1 (5′-GCACTTACACTCGCCACCTGA-3′). The amplicons were analyzed by DNA sequencing. The DNA sequences were aligned with the homologous sequences of the reference M. kansasii strain (ATCC12478) with multiple sequence alignments3.

Statistical Analysis

The differences in proportions of drug resistance between different M. kansasii subtypes were evaluated with chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The difference was considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Drug Susceptibility Testing

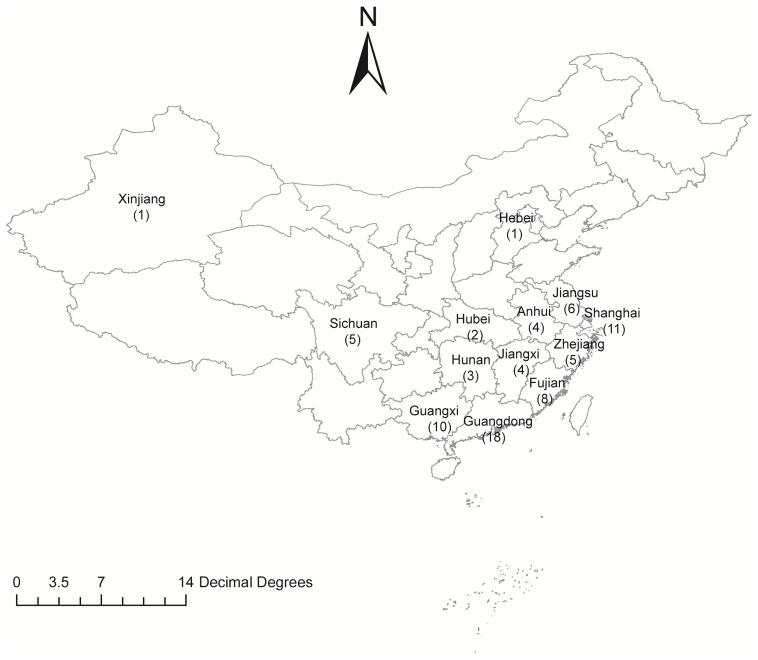

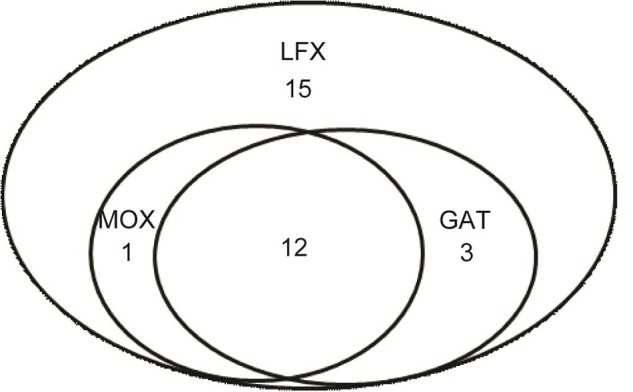

A total of 78 M. kansasii strains from 13 provinces of China were enrolled for further drug susceptibility testing in this study (Figure 1). The range of MICs of each antimicrobial agent for M. kansasii isolates is detailed qualitatively in Table 1. AMK was the most highly active against M. kansasii strains, and only 4 isolates (5.1%) exhibited in vitro resistance to AMK. Fluoroquinolone susceptibility was variable among MOX, LFX and GAT, the MIC50s and MIC90s of which were 0.25 μg/ml and 4 μg/ml for MOX, 2 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml for LFX, and 0.5 μg/ml and 4 μg/ml for GAT, respectively. When using the CLSI breakpoints, the percentage of LFX-resistant strains among the 78 M. kansasii isolates was 39.7% (31/78), which was significantly higher than that of MOX (16.7%, P = 0.001) and GAT (19.2%, P = 0.005). The levels of cross-resistance among fluoroquinolones are presented in Figure 2. Of the 31 isolates that were resistant to LFX, 13 (41.9%) and 15 (48.4%) isolates exhibited resistance to MOX and GAT, respectively. In addition, the isolates resistant to MOX and/or GAT were all resistant to LFX. For rifamycins, there were 44 (56.4%) and 27 (34.6%) isolates resistant to RIF and RFB, respectively. Statistical analysis revealed that the percentage of RFB-resistant isolates was significantly lower than that of RIF (P = 0.006).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of Mycobacterium kansasii isolates in this study.

Table 1.

In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium kansasii isolates against 20 antimicrobial agents enrolled in this study.

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC range (μg/ml) | MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) | No. of resistant strains (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLA | 0.063–128 | 0.25 | 128 | 16 (20.5) |

| AMK | 0.5–64 | 4 | 32 | 4 (5.1) |

| RIF | 0.063–128 | 2 | 32 | 44 (56.4) |

| RFB | 0.063–64 | 0.25 | 32 | 27 (34.6) |

| EMB | 0.13–64 | 2 | 32 | 16 (20.5) |

| LZD | 0.13–128 | 4 | 128 | 25 (32.1) |

| MOX | 0.063–16 | 0.25 | 4 | 13 (16.7) |

| LFX | 0.063–32 | 2 | 16 | 31 (39.7) |

| GAT | 0.063–16 | 0.5 | 4 | 15 (19.2) |

| SUL | 0.25–128 | 4 | 128 | 13 (16.7) |

| AZM | 0.5–128 | 16 | 32 | – |

| CAP | 0.063–128 | 1 | 32 | – |

| TGC | 0.25–128 | 64 | 128 | – |

| MER | 0.25–128 | 128 | 128 | – |

| MIN | 0.25–128 | 4 | 32 | – |

| STR | 1–128 | 8 | 128 | – |

| CFX | 2–128 | 128 | 128 | – |

| TOB | 0.5–128 | 8 | 64 | – |

| CLO | 0.06–128 | 1 | 64 | – |

| INH | 1–64 | 4 | 64 | – |

aINH, isoniazid; STR, streptomycin; CLA, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin; RIF, rifampicin; RFB, rifabutin; EMB, ethambutol; LZD, linezolid; MOX, moxifloxacin; LFX, levofloxacin; GAT, gatifloxacin; SUL, sulfamethoxazole; AZM, azithromycin; CAP, capreomycin; TGC, tigecycline; MER, meropenem; MIN, minocycline; CFX, cefoxitin; TOB, tobramycin; CLO, clofazimine.

bMIC50 represents the concentration required to inhibit the growth of 50% of the strains; MIC90 represents the concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of the strains.

FIGURE 2.

Cross-resistance to fluoroquinolones of Mycobacterium kansasii isolates.

We further analyzed the drug susceptibility of M. kansasii isolates against antimicrobial agents without the breakpoint values. Out of these ten drugs, CAP showed the most activity against M. kansasii, with a MIC50 of 1 μg/ml and an MIC90 of 32 μg/ml. In contrast, TGC, MER and CFX exhibited poor activity against M. kansasii, the MIC50s and MIC90s of which were higher than 64μg/ml.

Distribution of Subtypes

All the 78 M. kansasii isolates were genotyped by PDA method. As shown in Table 2, they were classified as four different subtypes, including subtype I, II, III, and IV. Of these subtypes, subtype I was the most frequent genotype in China, accounting for 71.8% (56/78) of M. kansasii isolates. In addition, there were 11 (14.1%), 8 (10.3%), and 3 (3.8%) isolates belonging to subtype II, III, and IV, respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of M. kansasii classified as different subtypes.

| Subtype | No. of isolates (%) | PCR-RFLP profiles of hsp65 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BstE II fragment lengths (bp) | Hae III fragment lengths (bp) | ||

| I | 56 (71.8) | 240, 210 | 140, 105, 80 |

| II | 11 (14.1) | 240, 135, 85 | 140, 105 |

| III | 8 (10.3) | 240, 135, 85 | 140, 95, 70 |

| IV | 3 (3.8) | 240, 125, 85 | 140, 115, 70 |

Association between Subtypes and Drug Susceptibility

We further explored the relationship between genetic subtypes and in vitro drug susceptibility of M. kansasii, which is summarized in Table 3. Overall, resistance to CLA was noted in 26.8% (15/56) of subtype I isolates, while only 4.5% (1/22) of isolates from other subtypes was resistant to CLA. Statistical analysis revealed that the proportion of CLA-resistance among subtype I was significantly higher than that among other subtypes (P = 0.031). Similarly, subtype I seemed more resistant to EMB (25.0% vs. 9.1%), MOX (33.9% vs. 9.1%), and GAT (23.2% vs. 9.1%) than other subtypes, while the difference was not significant (P > 0.05), which might be due to the small sample size. In addition, our data revealed that no statistically significant difference between subtype I and other subtypes in the prevalence of RIF-, RFB-, LZD-, and LFX-resistance (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Percentage of drug resistance among different subtypes of M. kansasii isolates.

| Antimicrobial agent | No. of resistant isolates (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype I (56) | Subtype II, III, and IV (22) | ||

| CLA | 15 (26.8) | 1 (4.5) | 0.031 |

| AMK | 4 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.572 |

| RIF | 31 (55.4) | 13 (59.1) | 0.765 |

| RFB | 19 (33.9) | 8 (36.4) | 0.839 |

| EMB | 14 (25.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.211 |

| LZD | 19 (25.0) | 6 (27.3) | 0.571 |

| MOX | 11 (33.9) | 2 (9.1) | 0.330 |

| LFX | 24 (42.9) | 7 (31.8) | 0.370 |

| GAT | 13 (23.2) | 2 (9.1) | 0.210 |

| SUL | 11 (19.6) | 2 (9.1) | 0.330 |

Mutations in 23S Ribosomal RNA Conferring CLA Resistance

As shown in Table 4, the presence of mutations in 23S rRNA was associated with 56.2% (9/16) of CLA-resistant isolates, while 7 (43.8%) of the 16 CLA-resistant isolates were found to have no mutations at positions 2058 and 2059. A total of two types of mutations were observed in 23S rRNA. The most frequent mutation conferring CLA resistance was A-to-T substitution at position 2058, and six isolates harboring this mutation showed resistant to CLA, the MICs of which ranged from 32 to 128 μg/ml. In addition, another substitution at position 2058 (A-to-C) was found in three CLA-resistant isolates.

Table 4.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MICs) of CLA and AZM and mutations in the 23S rRNA gene in CLA-resistant M. kansasii isolates.

| Mutation in 23S rRNA | MIC range of CLA (μg/ml) | MIC range of AZM (μg/ml) | No. of isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A2058T | 32–128 | 16–128 | 6 (37.5) |

| A2058C | 64–128 | 32–128 | 3 (18.8) |

| NA | 32–128 | 4–128 | 7 (43.8) |

| Total | 32–128 | 4–128 | 16 (100.0) |

Discussion

To our best knowledge, the present study is the first provided fundamental information on the drug susceptibility and molecular analysis of M. kansasii isolates from China. In keeping with previous reports, our results demonstrated that AMK exhibits favorable in vitro activity against M. kansasii isolates, which supports its important role in the initial treatment of M. kansasii infections (van Ingen et al., 2010; Cowman et al., 2016). Notably, we found that the prevalence of CLA-resistance was 20.5%, which was higher than that from Spain (0%) (Guna et al., 2005), Netherlands (1%) (van Ingen et al., 2010), Brazil (3%) (da Silva Telles et al., 2005), and UK (13%) (Cowman et al., 2016). Due to the satisfactory antibacterial activity and rare adverse effect, macrolides have been used as the first-choice treatment for respiratory tract infection (Yezli and Li, 2012). Numerous literatures have demonstrated that the misuse of macrolides is associated with emergency and increased prevalence of CLA-resistant bacteria in China (Wang et al., 1998, 2001; Chen et al., 2013), which may also serve as a major contributor to the high prevalence of CLA-resistant M. kansasii isolates in China. In vitro susceptibility of non-tuberculous mycobacteria against CLA exhibits excellent correlation with clinical outcomes (Cowman et al., 2016), the high proportion of CLA-resistant M. kansasii in China thus highlights the urgent need to perform in vitro CLA susceptibility testing before the initial treatment with regimen containing CLA.

The common in vitro resistance to LFX and RIF was observed from our data, indicating the inclusion of these drugs in the therapeutic regimen is controversial. However, the good activity of MOX was detected in this study, which is consistent to previous results from van Ingen et al (van Ingen et al., 2010). A recent study revealed that the combination of MOX and CLA is associated with attenuated CLA activity in a murine model (Kohno et al., 2007). Nevertheless, MOX is an alternative antimicrobial agent for the patients infected with CLA-resistant M. kansasii.

Point mutations at either position 2058 or 2059 in the 23S rRNA gene have been reported to confer macrolide resistance phenotypes in NTM species (Inagaki et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2014). For M. avium complex, almost 90% of CLA-resistant isolates harbor nucleotide substitutions in the 23S rRNA gene (Inagaki et al., 2011). In contrast, our data revealed that more than 40% of CLA-resistant M. kansasii isolates had no mutation at either position 2058 or 2059 of the 23S rRNA gene. The unsatisfactory correlation between in vitro CLA resistance and mutations of 23S rRNA indicates that other mechanisms, such as efflux pump and methylation of 23S rRNA, may be involved in CLA resistance for M. kansasii (Inagaki et al., 2011; Brown-Elliott et al., 2012).

Mycobacterium kansasii subtype I is the most frequent subtype isolated from humans in many geographic areas of the world (da Silva Telles et al., 2005). In agreement with previous reports, the subtype I is also the predominant genotype of M. kansasii in China, the prevalence of which is similar to that in Switzerland (68%) (Taillard et al., 2003), although it is lower than that in Spain (98%) (Santin et al., 2004) and Brazil (98%) (da Silva Telles et al., 2005), and higher than that in Germany (33%) (Richter et al., 1999), Poland (40%) (Bakula et al., 2013), and France (43%) (Alcaide et al., 1997). Hence, the distribution of subtype I exhibits geographical diversity, which may be associated with the existence of different ecosystems for these microorganisms (Taillard et al., 2003). In addition, only 14.1% of M. kansasii isolates in this study were classified as subtype II, lower than data from previous studies (Alcaide et al., 1997; Richter et al., 1999). Different from Subtype I, Subtype II is considered as an opportunistic agent, which seems to be more frequently isolated from HIV-infected patients (Taillard et al., 2003). Thus, the low prevalence of subtype II may be due to the low epidemic of HIV in China.

Another important finding of the current study is that M. kansasii subtype I is associated with CLA resistance in China. Subtype I is the most common cause responsible for human infection by M. kansasii, while the other subtypes are likely to be isolated from environmental samples (Taillard et al., 2003). We speculate that the different drug susceptibility profiles between subtype I and other subtypes may reflect their significant difference in ecological niches. Due to more frequent exposure to antibiotic selection pressure from human, subtype I emerges the higher proportion of drug resistance to increase adaptability in hosts. Given that CLA-based drug regimens are effective options for treatment of M. kansasii infection, the statistical difference observed in CLA-resistance between subtype I and other subtypes is reasonable. In line to our hypothesis, we also found that subtype I was more likely to be resistant to EMB, MOX, and GAT than other subtypes. Unfortunately, because the small sample size undermines the statistical power, the difference was not statistically significant. Further study with more than 200 isolates will be required to determine the potential relationship between M. kansasii subtypes and drug susceptibility profiles.

There were several obvious limitations in this study. First, although chronic pulmonary disease is the most frequent clinical manifestation of NTM infection, it also causes extrapulmonary diseases, such as lymphatic, skin and soft tissue diseases (Griffith et al., 2007). Considering the predominance of M. kansasii subtype I in the pulmonary diseases from our observations, it is important to investigate the distribution of difference subtypes in the extrapulmonary infections due to M. kansasii. Unfortunately, the isolates enrolled in this study were only collected from suspected pulmonary tuberculosis patients, which impedes the further analysis. Second, HIV status in patients, who are at a high risk for NTM diseases (Henkle and Winthrop, 2015), was not collected. Due to the relative low prevalence of HIV in China, routine HIV examination is not performed among TB patients. On the basis of our findings, future studies will be done to validate the distribution of M. kansasii subtypes in these special populations, which will extend our knowledge of host preference and bacterial pathogenicity among various M. kansasii subtypes.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that AMK is the most active agent against M. kansasii in vitro, while the high proportion of CLA resistance is noted in M. kansasii isolates from China. Further PRA analysis reveals that subtype I is the predominant genotype of M. kansasii in China. In addition, M. kansasii subtype I is associated with CLA resistance. Given the CLA-containing regimen frequently used in the treatment M. kansasii, the high proportion of CLA resistance in China highlights the urgent need to perform in vitro CLA susceptibility testing before the initial treatment with CLA.

Author Contributions

YL, YP, YZ, and CW designed this study. YL, YP, and HZ performed experiments. YL, YP, and XT interpreted the data. YL, YP, and CW wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their cooperation and technical help.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Program of China (2015ZX10003003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81400037) and Beijing Hospital Nova Project (BJ-2016-038).

References

- Alcaide F., Benitez M. A., Martin R. (1999). Epidemiology of Mycobacterium kansasii. Ann. Intern. Med. 131 310–311. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-4-199908170-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide F., Richter I., Bernasconi C., Springer B., Hagenau C., Schulze-Robbecke R., et al. (1997). Heterogeneity and clonality among isolates of Mycobacterium kansasii: implications for epidemiological and pathogenicity studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35 1959–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakula Z., Safianowska A., Nowacka-Mazurek M., Bielecki J., Jagielski T. (2013). Short communication: subtyping of Mycobacterium kansasii by PCR-restriction enzyme analysis of the hsp65 gene. Biomed Res Int. 2013:178725 10.1155/2013/178725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Elliott B. A., Nash K. A., Wallace R. J., Jr. (2012). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, drug resistance mechanisms, and therapy of infections with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25 545–582. 10.1128/CMR.05030-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo R. E., Campo C. E. (1997). Mycobacterium kansasii disease in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin. Infect. Dis 24 1233–1238. 10.1086/513666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. S., Yin Y. P., Wei W. H., Wang H. C., Peng R. R., Zheng H. P., et al. (2013). High prevalence of azithromycin resistance to Treponema pallidum in geographically different areas in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19 975–979. 10.1111/1469-0691.12098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2011). Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardia, and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes; Approved Standard CLSI Document M24-A2, 2nd Edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowman S., Burns K., Benson S., Wilson R., Loebinger M. R. (2016). The antimicrobial susceptibility of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. J. Infect. 72 324–331. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Telles M. A., Chimara E., Ferrazoli L., Riley L. W. (2005). Mycobacterium kansasii: antibiotic susceptibility and PCR-restriction analysis of clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 54 975–979. 10.1099/jmm.0.45965-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. E., Aksamit T., Brown-Elliott B. A., Catanzaro A., Daley C., Gordin F., et al. (2007). An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175 367–416. 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay D. R. (1996). Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Ann. Pharmacother. 30 819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guna R., Munoz C., Dominguez V., Garcia-Garcia A., Galvez J., de Julian-Ortiz J. V., et al. (2005). In vitro activity of linezolid, clarithromycin and moxifloxacin against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55 950–953. 10.1093/jac/dki111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkle E., Winthrop K. L. (2015). Nontuberculous mycobacteria infections in immunosuppressed hosts. Clin. Chest Med. 36 91–99. 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefsloot W., van Ingen J., Andrejak C., Angeby K., Bauriaud R., Bemer P., et al. (2013). The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur. Respir. J. 42 1604–1613. 10.1183/09031936.00149212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach M., Somoskovi A., Homke R., Ritter C., Bottger E. C. (2013). Drug susceptibility distributions in slowly growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria using MGIT 960 TB eXiST. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303 270–276. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T., Yagi T., Ichikawa K., Nakagawa T., Moriyama M., Uchiya K., et al. (2011). Evaluation of a rapid detection method of clarithromycin resistance genes in Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 722–729. 10.1093/jac/dkq536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno Y., Ohno H., Miyazaki Y., Higashiyama Y., Yanagihara K., Hirakata Y., et al. (2007). In vitro and in vivo activities of novel fluoroquinolones alone and in combination with clarithromycin against clinically isolated Mycobacterium avium complex strains in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 4071–4076. 10.1128/AAC.00410-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSwiggan D. A., Collins C. H. (1974). The isolation of M. kansasii and M. xenopi from water systems. Tubercle 55 291–297. 10.1016/0041-3879(74)90038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M., Prod’Hom G., Raskine L., LePennec M. P., Vincent V. (1997). Genotypic characterization of five subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintado V., Gomez-Mampaso E., Martin-Davila P., Cobo J., Navas E., Quereda C., et al. (1999). Mycobacterium kansasii infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18 582–586. 10.1007/s100960050351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevots D. R., Marras T. K. (2015). Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin. Chest Med. 36 13–34. 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter E., Niemann S., Rusch-Gerdes S., Hoffner S. (1999). Identification of Mycobacterium kansasii by using a DNA probe (AccuProbe) and molecular techniques. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37 964–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts W. M., O’Shaughnessy T. C., van Ingen J. (2014). Human-to-human transmission of Mycobacterium kansasii or victims of a shared source? Eur. Respir. J. 44 1085–1087. 10.1183/09031936.00066614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C. D., Claxton P., Doig C., Seagar A. L., Rayner A., Laurenson I. F. (2014). Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: a retrospective review of Scottish isolates from 2000 to 2010. Thorax 69 593–595. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santin M., Alcaide F., Benitez M. A., Salazar A., Ardanuy C., Podzamczer D., et al. (2004). Incidence and molecular typing of Mycobacterium kansasii in a defined geographical area in Catalonia, Spain. Epidemiol. Infect. 132 425–432. 10.1017/S095026880300150X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steadham J. E. (1980). High-catalase strains of Mycobacterium kansasii isolated from water in Texas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11 496–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillard C., Greub G., Weber R., Pfyffer G. E., Bodmer T., Zimmerli S., et al. (2003). Clinical implications of Mycobacterium kansasii species heterogeneity: Swiss National Survey. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 1240–1244. 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1240-1244.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenti A., Marchesi F., Balz M., Bally F., Bottger E. C., Bodmer T. (1993). Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 175–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ingen J., van der Laan T., Dekhuijzen R., Boeree M., van Soolingen D. (2010). In vitro drug susceptibility of 2275 clinical non-tuberculous Mycobacterium isolates of 49 species in The Netherlands. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35 169–173. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Huebner R., Chen M., Klugman K. (1998). Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Streptococcus pneumoniae in china and comparison of MICs by agar dilution and E-test methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 2633–2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Zhang Y., Zhu D., Wang F. (2001). Prevalence and phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Shanghai, China. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39 187–189. 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00217-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzig R. S., Fazal B. A., Mera R. M., Mushatt D. M., Dejace P. M., Greer D. L., et al. (1995). Clinical manifestations and implications of coinfection with Mycobacterium kansasii and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin. Infect. Dis 21 77–85. 10.1093/clinids/21.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yezli S., Li H. (2012). Antibiotic resistance amongst healthcare-associated pathogens in China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40 389–397. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Pang Y., Wang Y., Cohen C., Zhao Y., Liu C. (2015). Differences in risk factors and drug susceptibility between Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare lung diseases in China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 45 491–495. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang Y., Pang Y. (2014). Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characterization of Mycobacterium intracellulare in China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 27 332–338. 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Xu S., Wang L., Chin D. P., Wang S., Jiang G., et al. (2012). National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 366 2161–2170. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]