Abstract

Mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2 (MASP-2) has been described as the essential enzyme for the lectin pathway (LP) of complement activation. Since there is strong published evidence indicating that complement activation via the LP critically contributes to ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury, we assessed the effect of MASP-2 deficiency in an isogenic mouse model of renal transplantation. The experimental transplantation model used included nephrectomy of the remaining native kidney at d 5 post-transplantation. While wild-type (WT) kidneys grafted into WT recipients (n=7) developed acute renal failure (control group), WT grafts transplanted into MASP-2-deficient recipients (n=7) showed significantly better kidney function, less C3 deposition, and less IR injury. In the absence of donor or recipient complement C4 (n=7), the WT to WT phenotype was preserved, indicating that the MASP-2-mediated damage was independent of C4 activation. This C4-bypass MASP-2 activity was confirmed in mice deficient for both MASP-2 and C4 (n=7), where the protection from postoperative acute renal failure was no greater than in mice with MASP-2 deficiency alone. Our study highlights the role of LP activation in renal IR injury and indicates that injury occurs through MASP-2-dependent activation events independent of C4.—Asgari, E., Farrar, C. A., Lynch, N., Ali, Y. M., Roscher, S., Stover, C., Zhou, W., Schwaeble, W. J., Sacks, S. H. Mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2 is critical for the development of renal ischemia reperfusion injury and mediates tissue injury in the absence of complement C4.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, inflammation

Ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury causes significant morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation (1). Ischemic injury to the kidney is a cause of delayed graft function, which has been shown to increase acute rejection episodes and reduce long-term graft survival (2). During ischemia, hypoxic and anoxic cell injury occurs, leading to dramatic changes in epithelial and endothelial cell morphology and protein/receptor surface expression profile. Reperfusion allows the flow of blood back into the damaged organ. Elements of the innate immune system within the blood recognize the ischemia-induced changes on exposed cells that result in an inflammatory response and subsequent increase in tissue injury (3). The complement system is well established as an important mediator of the innate immune defense and inflammation (4). It consists of more than 30 components including serum proteins, membrane-bound regulators, and receptors and is activated via 3 pathways: the classical pathway (CP), the lectin pathway (LP), and the alternative pathway (AP). The CP is antibody dependent and is activated following binding of C1q within the C1 complex to antigen-antibody complexes, whereas in the LP, pattern recognition molecules, such as mannan-binding lectin (MBL), collectin 11 (CL-11), and ficolins, bind to specific carbohydrate residues on bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotic pathogens or altered self cells, such as apoptotic, necrotic, or malignant cells (5–7), following which the enzymatic activity of MBL-associated serine proteases (MASPs) triggers the activation of the pathway. The AP is activated when activated C3 (C3b) binds to pathogens or other potential activating surfaces in the presence of factor B (FB) and factor D. Activated C3 is formed spontaneously in plasma through cleavage of C3 via the “C3 tick over mechanism” (8). Several studies have demonstrated that complement activation plays a major pathogenic role in IR injury. This effect varies depending on the organ involved and the animal model used (9). In the murine model of kidney IR injury, CP activation has been shown not to have a major role, because mice deficient in C4 are not protected from IR injury (10). This is underlined by a later study using C1q-deficient mice in a model of myocardial IR injury, which revealed that C1q-deficient mice (which are totally deficient of CP functional activity) are not only not protected from myocardial IR injury, but also appear to have bigger infarct volumes than the wild-type (WT) controls (11, 12). Deficiency of FB, as well as use of FB inhibitors, has been shown to have a protective effect in murine kidney IR injury, suggesting a role for the AP (13–15); however, it is not clear what triggers the AP in the first place. Other studies have underlined the role of the LP in renal IR injury. While a deficiency of C4 has not been shown to be protective (as the present textbook representation of the activation events leading to complement activation via the LP would imply), the phenotype of MBL-A and MBL-C double-deficient (MBL-null) mice in native kidney IR injury models, however, have revealed a degree of protection from renal IR (16, 17).

An effect of the LP has also been shown in a mouse model of cerebral IR injury where MBL-null mice had smaller infarct size compared to their WT controls. This finding is underlined by a clinical study showing that stroke patients with single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) leading to absent or low MBL plasma levels presented with a statistically significant advantage with lower infarct sizes and less severe clinical symptoms when compared to an age- and sex-matched MBL-sufficient control group (18, 19). MBL-null mice have been shown to incur less damage in a model of skeletal muscle IR injury (20). Clear evidence for the involvement of the LP in intestinal IR injury was also demonstrated when comparing the severity of IR injury in MBL-null mice with that WT controls (11). The same MBL-null mouse line also presented with smaller infarct sizes in an experimental mouse model of myocardial IR injury leading to a significantly better preservation of left ventricular ejection fraction (12). The use of monoclonal antibody-based inhibitors of MBL functional activity has been shown to significantly reduce IR damage in a rat model of myocardial IR injury (21). Interestingly, there has been a recent shift in paradigm as to which complement activation route mediates IR injury: Initial observations on complement-mediated IR injury assumed that the CP activation was instrumental in triggering injury (at that time, the conclusion was based on antibody dependency and detection of C3 deposition in injured areas; refs. 22, 23), while more recent papers of the same research group revealed that IgM-mediated IR injury is likely to be triggered by binding of MBL to IgM molecules targeted toward a self nonmuscle myosin heavy chain in murine models of intestinal and skeletal IR injury (24). This implies that it is the LP that plays the key role in IR injury. This viewpoint is also supported by subsequent studies showing that tissue damage in intestinal and myocardial IR injury is dependent on the presence of both IgM and MBL (25, 26). Deficiency of C1q was not protective, suggesting that the effect of IgM was independent of the CP (27). In a more recent study, binding of MBL-A to meprins, which are highly glycosylated zinc metalloproteases present on kidney proximal tubules, was shown to activate the LP of complement and cause injury following kidney IR (28). The availability of a mouse line with a targeted deficiency of the essential LP effector component MASP-2 provided the first model of total LP deficiency. Both MASP-2−/− and WT mice treated with an anti-MASP-2 specific inhibitory antibody were significantly protected from cardiac and intestinal IR injury (29), demonstrating that complement-mediated IR injury is primarily MASP-2 dependent. Whereas earlier observations in cardiac and intestinal models focused on native organ ischemia, the advantage of the renal isograft model used here is the relevance to whole-organ transplantation, where both cold and warm ischemia are pathogenic factors. Our observation is important because it highlights MASP-2 as a key potential target for therapeutic intervention in the commonest type of solid organ transplant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Homozygous MASP-2-deficient (MASP-2−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 (B6) background (back-crossed for more than 11 generations) were established in the W.J.S. laboratory at the University of Leicester. Age- and sex-matched WT B6 control animals were purchased from Harlan UK Ltd. (Bicester, UK). C4-deficient (C4−/−; ref. 30) mice were obtained from Prof. Michael C. Carroll's group (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA). C4/MASP-2−/− double-knockout mice were generated by back-crossing the 2 strains for 10 generations in our department. Animals were maintained in pathogen-free conditions. Female mice (8–10 wk old) were used throughout. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986.

IR injury in native kidneys

The renal ischemia was induced using the protocol described previously (10). Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of oxygen and isoflurane (Abbot Laboratories, Maidenhead, UK) and kept warm using a heated mat throughout the procedure. Following a midline abdominal incision, renal arteries and veins were bilaterally occluded for 55 min with microaneurysm clamps (Codman, Wokingham, UK). After removal of the clamps, 0.4 ml of warm saline was placed in the abdomen, and the incision was sutured. Animals were kept in a heated chamber for 6 h, after which they were euthanized and their kidneys removed for histological examination.

Mouse kidney transplantation

A well-described protocol of mouse transplantation (31) was used. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of oxygen and isoflurane (Abbot Laboratories) and kept warm using a heated mat throughout the procedure. The left kidney was surgically removed from the donor along with a renal arterial patch and renal vein. The ureter was separated and cut close to the bladder. The kidney was then placed on ice for a period of cold ischemia lasting 30 min. The recipient native right kidney was removed, and microaneurysm clamps were placed over the aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC). Incisions were made in the recipient aorta and IVC, to which donor artery and vein were anastomosed. Clamps were removed, whereupon the transplanted kidney was observed to ensure revascularization. The donor ureter was connected to the recipient bladder, after which 0.5 ml of warm saline was placed in the body cavity and the abdomen closed. Recipients were kept in a heated chamber for 24 h to aid recovery. The remaining native kidney was removed on d 5, and the animal was euthanized 24 h later. Blood and transplanted kidneys were collected for assessment of renal function and tissue damage, respectively.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurement

BUN was measured using a standard urease kit (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) based on the measurement of coupled enzyme reactions involving urease and glutamate dehydrogenase. Readout was determined by rate of decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, which is directly proportional to the BUN concentration of the serum sample.

Paraffin embedding and PAS staining

Transplanted kidneys were removed from the mice, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Then 4 μm sections were cut and stained using PAS reaction. The slides were evaluated by 2 experienced investigators in a blinded fashion at ×400 view to assess tubular epithelial necrosis, tubular dilatation, and cast formation within the corticomedullary junction. From each stained section, 10–12 fields were reviewed using a 5-point scale, and the percentage of tubules showing the described features was scored as following: 0, normal kidney; 1, <10%; 2, 11–25%; 3, 26–75%; and 4, >75%.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections (4 μm) from snap-frozen kidneys were fixed in acetone for 10 min and air-dried. Slides were then incubated with primary antibody for detection of C3d, using a purified Ig fraction of rabbit anti-human serum (Dako, Cambridge, UK) which is cross-reactive with mouse C3d (32). FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) was used as secondary antibody. Deposited C3d in the corticomedullary junction was quantified using LUCIA image-analysis software (Jencons-PLS, Leighton Buzzard, UK). At a view of ×400, for each animal, 20 fields from 2 stained kidney sections were photographed, and areas of positive staining were highlighted and calculated. For MASP-2 staining, a rat anti-mouse MASP-2 mAb (clone 1.7) was established against recombinant mouse MASP-2 at the University of Leicester. Binding of anti-MASP-2 mAb was detected using rabbit anti-rat horseradish peroxidase (Dako).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between the 2 groups were performed using unpaired t test with Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are reported as means ± sem.

RESULTS

MASP-2 deposition in renal IR injury

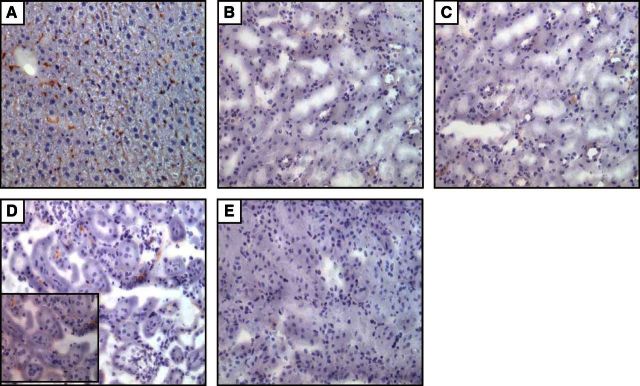

We performed an initial renal isograft study in which WT kidney was transplanted into WT recipients following a period of cold ischemia of the donor organ, as described above. Since it is reported that MASP-2 expression is exclusive to the liver and is not present in the kidney (33), any staining for MASP-2 in the transplanted kidney must arise by deposition from the circulating pool. In the transplant protocol employed, the transplanted kidney was removed for analysis on d 6 post-transplantation, i.e., on the day following the removal of the remaining native kidney of the recipient. However, at 6 d post-transplantation immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of MASP-2 in the transplanted kidney (Fig. 1C). Control studies using normal mouse liver positively identified MASP-2, validating the staining method (Fig. 1A). Since the half-life of MASP-2 is relatively short (26 min at 37°C and pH 7.5; ref. 34), and since the peak tissue injury following the induction of IR occurs within the first 24 h of reperfusion (35), we conducted an additional experiment (in native mouse kidney) to determine whether MASP-2 could be detected at 6 h postreperfusion following the occlusion of the renal pedicle. In this experiment, MASP-2 was clearly detected at the peritubular surface, as well as at the luminal surface of the vulnerable tubules of the corticomedullary junction (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that MASP-2 is deposited from the circulation during the onset of renal IR injury.

Figure 1.

A–C) Immunohistochemical staining of MASP-2 in liver (A), nonischemic kidney (B), and transplanted kidney (C) of WT B6 mice on d 6. D) Kidney tissue 6 h after IR injury. Inset: higher-magnification view (×400) showing distinctive peritubular staining of MASP-2. E) Kidney tissue from normal MASP-2−/− mouse. The brown color indicates the presence of MASP-2, which is abundant in the liver. MASP-2 is not detectable in the WT transplanted kidney 6 d after surgery but is clearly present 6 h after IR injury. The MASP-2−/− kidney has negative staining. View: ×200.

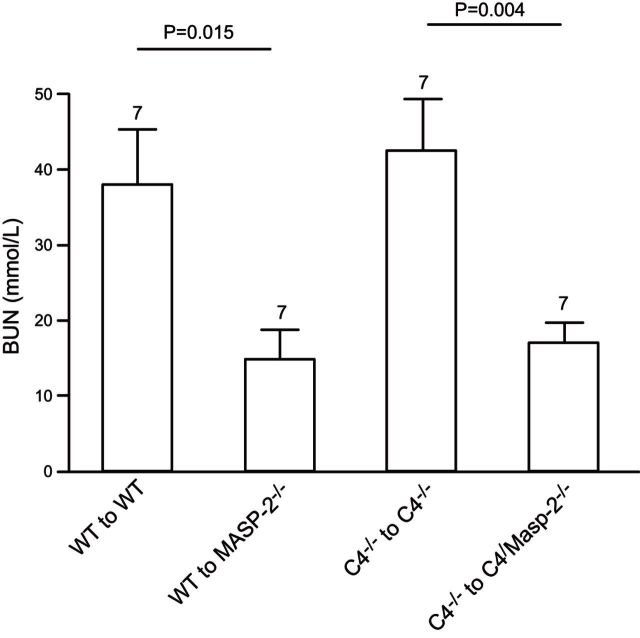

Renal IR injury is dependent on the LP via MASP-2, and this effect is independent of C4

To assess the role of the LP via MASP-2 in kidney IR injury, and to establish whether this effect is independent of C4 as described in previous studies (29, 36), renal function and kidney tubular damage were assessed and compared in mice subjected to kidney transplantation in 4 different groups. These included WT to WT (n=7), WT to MASP-2−/− (n=7), C4−/− to C4−/− (n=7), and, finally, to determine whether deficiency of C4 has any additional benefit to MASP-2 deficiency, C4−/− to C4/MASP-2−/− (n=7). The remaining recipient native kidney was removed on d 5, ensuring that subsequent renal function was dependent on the transplanted kidney alone. Blood and tissue samples were obtained from mice on d 6 post-transplantation. The BUN in MASP-2−/− mice was significantly lower than the WT group. A key observation was that in the complete absence of both donor and recipient C4, the WT to WT phenotype was preserved, indicating that the MASP-2-mediated damage was independent of C4. This was confirmed in mice deficient for both MASP-2 and C4, where the protection from postoperative acute renal failure was no greater than in mice with MASP-2 deficiency alone (Fig. 2). These results indicate that the LP plays a significant role in the transplant model of kidney IR injury via MASP-2, and this effect is independent of C4.

Figure 2.

Absence of MASP-2 is protective in a transplant model of kidney IR injury. Measurement of renal function in 4 groups of transplant recipients 6 d after transplantation. Transplantation was performed with 30 min of cold ischemia and 40 min of warm ischemia time. One native kidney was excised at the time of transplantation, and the remaining native kidney was removed at d 5 post-transplantation. Mice were killed at d 6, and blood samples and tissue were collected for analysis. Number above each column indicates the number of transplants performed in each group. Bars represent means ± sd. Value of P < 0.05 is considered significant.

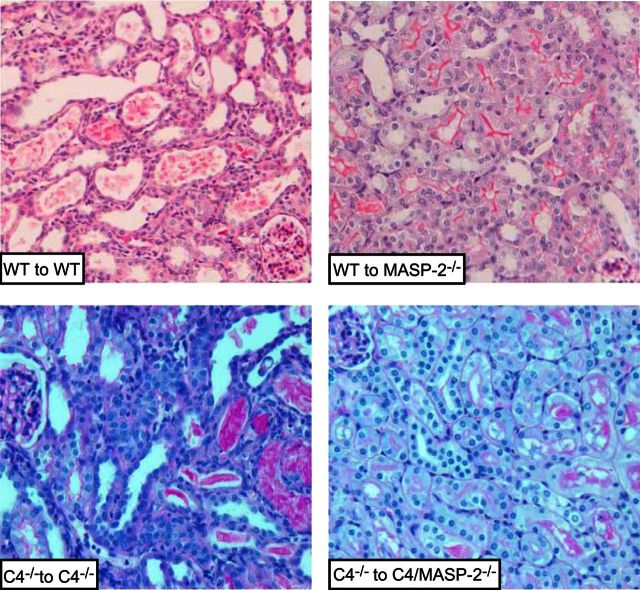

The severity of tubular damage in transplanted kidneys was proportional to functional impairment as determined by BUN. The WT to WT and C4−/− to C4−/− groups have significant tubular damage compared with both WT to MASP-2−/− and C4−/− to C4/MASP-2−/− groups (Fig. 3 and Table 1), indicating that deficiency of MASP-2 is protective, an effect that is independent of C4 (as C4−/− had similar tissue damage to WT).

Figure 3.

Effect of IR injury on renal tissue morphology in 4 transplant groups. PAS staining: images of representative histology samples from renal transplant groups. In both WT and C4−/− transplant recipients, there are visible signs of tubular damage, including tubular thinning and dilatation and formation of hyaline casts in the tubules. Conversely, MASP-2−/− and C4/MASP-2−/− transplanted kidneys show minimal signs of injury. View: ×400.

Table 1.

Severity score of tubular damage in 4 transplant groups

| Group | Transplants (n) | Severity score |

|---|---|---|

| WT to WT | 7 | 3.14 ± 1.46 |

| WT to MASP−/− | 7 | 1.57 ± 0.78 |

| C4−/− to C4−/− | 7 | 3.29 ± 1.13 |

| C4−/− to C4/MASP−/− | 7 | 1.71 ± 0.75 |

WT to MASP-2−/− group had significantly less damage score compared with WT to WT (P=0.027). Similarly, C4/MASP-2−/− animals had more preserved kidney tissue compared with the C4−/− to C4−/− transplants (P=0.021). A concordance correlation coefficient pc > 0.95 was achieved, thereby demonstrating substantial agreement between the 2 investigators. Score values are means ± sem.

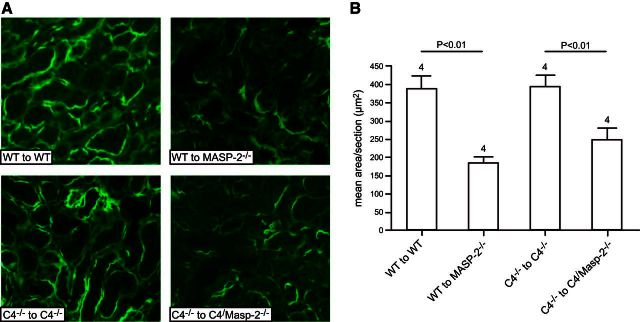

MASP-2−/− mice had reduced C3d deposition compared with WT and C4−/− mice

Using immunofluorescent microscopy, C3d deposition was compared in different study groups. As in previous studies, we found C3d deposition in normal nonmanipulated WT mice (Supplemental Fig. S1). However, C3d deposition was increased in WT to WT and C4−/− to C4−/− kidney transplants compared with WT to MASP-2−/− and C4−/− to C4/MASP-2−/− (Fig. 4). This indicates a reduction in injury to the kidney in the absence of recipient MASP-2 as a result of reduced C3 cleavage by LP components that are MASP-2 dependent. It is also possible that MASP-2-mediated tissue injury is independent of complement activation, and the observed complement activity occurs following the induced injury.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of complement split product C3d. A) Deposition of C3d was observed on the basolateral surface of the tubular epithelial cells in all groups. However, in WT and C4−/− recipients, C3d deposition was more extensive, with increased intensity compared to MASP-2−/− and C4/MASP-2−/− recipients. View: ×400. B) In each group, mean areas of positive C3d deposition were determined within 20 high-powered fields from 4 animals (see Materials and Methods).

DISCUSSION

IR injury in transplantation remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. In the past decade, many gene-knockout studies have shown an effect of complement activation on the pathogenesis of IR injury of kidney and other organs. Specifically, studies of genetically modified mice have identified roles for complement components MBL, FB, C3, C5, C6, and C5a receptor (10, 15, 16, 37). Other studies have used complement-blocking agents to assess the effect on IR injury. A C5a receptor antagonist added to kidney preservative solution during cold ischemia led to increased graft survival (38), and gene silencing of complement C5a receptor 2 d prior to induction of IR in a mouse model was found to have a protective effect from injury (39). In addition, therapeutic regulators that inhibit the C3 and C5 convertases generated by all complement activation pathways have reduced IR injury in a rat renal isograft model (40). Collectively, these studies indicate that following renal ischemia, complement activation is mediated by the LP and amplified via the AP, leading to the cleavage of C3 and formation of the effectors C5a and C5b-9. A recent study of renal IR injury in a rat model confirmed a role for MBL in the initiation of the tubular injury (41). However, in this study, there was no protection by downstream complement inhibition, applying either monoclonal anti-C5 antibody or complement depletion with cobra venom factor (CVF), suggesting that the observed complement-independent mechanism of injury was induced directly via MBL. Alternatively, it is possible that limited tissue penetration of large therapeutic agents, such as IgG or CVF, prevented these agents from reaching the interstitial space, the site of complement activation mediated by IR insult (42). Hence, limited efficacy of these therapeutic agents in the context of renal reperfusion damage could have explained this discrepancy.

Despite confirmation that complement effector molecules mediate IR injury in various models, the trigger mechanism leading to initiation of complement activation is not yet identified. Understanding the precise initiating pathways will not only help to define molecular changes in ischemic tissue that trigger inflammatory pathways but will also lead to improvement in the selectivity and efficiency of potential treatment targets. The observation that C4 deficiency has not shown any protective effect in our model of kidney IR injury contrasts with the significant protective phenotype of MASP-2 deficiency and implies that MASP-2 drives renal IR injury independent of C4. MBL-stimulated complement activation in C2-deficient serum has been previously reported, demonstrating the presence of a C2 bypass pathway, suggesting that other elements could have a role in cleaving C3 and activating the complement pathway (36), though this observation was made in human patients and not mice. The present data confirm the importance of the LP molecule MASP-2 in a mouse kidney isograft model of IR damage, which, together with the published data (25–28, 43, 44), suggests that MBL-mediated cleavage of MASP-2 results in complement deposition on the renal tubular epithelium and leads to acute isograft injury. The absence of MASP-2 from the recipient mouse reduced the deposition of C3 on the renal tubules, in a manner that was protective against renal dysfunction, suggesting that MASP-2 is a potential therapeutic target for preventing postischemic acute renal damage in the transplanted organ. The reduction in C3 deposition noted on the tubule surface is indicative of a complement-mediated mechanism triggered via MASP-2. However, a complement-independent mechanism initiated by the LP, such as proposed by van der Pol et al. (41), where MBL is shown to induce renal tubular injury independent of complement activation, is not excluded, since complement deposition could have been a consequence of the injury rather than a cause of it.

Further work is needed to elucidate the mechanisms of MASP-2 in the pathogenesis of renal reperfusion damage to determine whether there are complement-independent as well as complement-dependent effects of MASP-2 induced by renal transplant ischemia.

Most murine studies are based on native kidney IR injury. However, in conjunction with the well-established effects of warm ischemia and reperfusion to organ damage in these models, the deleterious effects of cold ischemia and rewarming to whole transplanted organ need to be considered. To investigate the effects of cold and warm ischemia on kidney IR injury without inducing an immune response, we employed a mouse isograft model of kidney transplantation.

In this study, we have shown that in a kidney transplant model of IR, absence of MASP-2, which leads to a total loss of LP functional activity (29), significantly protects the organ from IR injury. In contrast to the previously studied MBL-null mice (which may still maintain residual LP functional activity via CL-11 or ficolin-mediated MASP-2 activation; ref. 7), MASP-2-deficient mice have no residual LP functional activity. Our results clearly demonstrate a critical role for MASP-2 in kidney IR injury.

Although our experiments demonstrated reduced C3d deposition in MASP-2-deficient animals post-transplantation (indicating that IR damage is complement dependent), the possibility remains that MASP-2 can also contribute a complement-independent injury that is secondarily amplified by the deposition of complement on the injured tissue, perhaps by the AP. In the latter case, MASP-2 should have an effect in the absence of C3, and double-deficient animals (lacking MASP-2 and C3) should be further protected compared with C3 deficiency alone. If the protective effect of both MASP-2 and C3 deficiency were not additive, this would indicate an interdependent mechanism, in which MASP-2 leads to the cleavage of C3 (bypassing C4).

One of the limitations of our study is that in this model, the peak injury (i.e., the first 24 to 48 h post-transplantation) is missed because the transplanted kidney is collected for analysis at d 6. Ideally, both native kidneys should be removed at the time of transplantation to reflect the real-life situation. However, from our experience the mice do not survive the injury if both kidneys are removed at this time. Although MASP-2 deposition could not be identified within the kidney on d 6 post-transplantation, its presence was shown in the kidney tubules 6 h post-IR injury of native kidney. Morphologically, the renal lesions following the induction of IR injury in native and transplanted kidney are indistinguishable. In both cases the severity of the injury peaks within the first 24–48 h of reperfusion. Furthermore the pattern of complement deposition (predominantly on the basolateral surface of the renal tubule in the outer medulla/inner cortex) is the same in both cases. Since LP involvement has now been demonstrated for both native and transplanted kidney, it is possible to infer that MASP-2 is deposited in the transplant organ at a time corresponding to the native kidney, demonstrated here. The absence of MASP-2 staining in the 6-d post-transplant kidney suggests the amount of MASP-2 was below the limit of detection at this time point, consistent with both the short half-life of MASP-2 and low MASP-2 concentration in plasma (29, 34).

In summary, our findings confirm a requirement for MASP-2 in the pathogenesis of renal isograft IR injury. The mechanism leading to renal IR injury is independent of C4 but is associated with C3 deposition on the tubular surface. The precise trigger mechanisms leading to activation of MASP-2 and consequently cleavage of C3 and C5 will be of considerable interest to ongoing research, because it may identify new pathogenic targets on ischemic tissue and reveal a nonconventional route of LP-dependent complement activation. Inhibition of the LP effector enzyme MASP-2 is likely to provide an effective therapeutic approach to limit renal IR injury during transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 079772 from The Wellcome Trust to W.J.S. and S.H.S., Kidney Research UK grant TF9 to E.A., and the Medical Research Council Centre for Transplantation, Guy's Hospital, King's College and the Department of Health, National Institute for Health Research comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy's and St. Thomas' National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London and King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

MASP-2-deficient mice were produced by C.S., and anti-MASP-2 mAb was produced by Y.M.A. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. W.J.S. and S.H.S. equally share the senior authorship.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AP

- alternative pathway

- B6

- C57BL/6

- BUN

- blood urea nitrogen

- CL-11

- collectin 11

- CP

- classical pathway

- CVF

- cobra venom factor

- FB

- factor B

- IR

- ischemia reperfusion

- IVC

- inferior vena cava

- LP

- lectin pathway

- MASP

- mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease

- MASP-2

- mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2

- MBL

- mannan-binding lectin

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism

- WT

- wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1. Damman J., Schuurs T. A., Ploeg R. J., Seelen M. A. (2008) Complement and renal transplantation: from donor to recipient. Transplantation 85, 923–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shoskes D. A., Cecka J. M. (1998) Deleterious effects of delayed graft function in cadaveric renal transplant recipients independent of acute rejection. Transplantation 66, 1697–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boros P., Bromberg J. S. (2006) New cellular and molecular immune pathways in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transplant. 6, 652–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mastellos D., Morikis D., Isaacs S. N., Holland M. C., Strey C. W., Lambris J. D. (2003) Complement: structure, functions, evolution, and viral molecular mimicry. Immunol. Res. 27, 367–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collard C. D., Vakeva A., Morrissey M. A., Agah A., Rollins S. A., Reenstra W. R., Buras J. A., Meri S., Stahl G. L. (2000) Complement activation after oxidative stress: role of the lectin complement pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 156, 1549–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fujita T. (2002) Evolution of the lectin-complement pathway and its role in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ali Y. M., Lynch N. J., Haleem K. S., Fujita T., Endo Y., Hansen S., Holmskov U., Takahashi K., Stahl G. L., Dudler T., Girija U. V., Wallis R., Kadioglu A., Stover C. M., Andrew P. W., Schwaeble W. J. (2012) The lectin pathway of complement activation is a critical component of the innate immune response to pneumococcal infection. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lachmann P. J., Halbwachs L. (1975) The influence of C3b inactivator (KAF) concentration on the ability of serum to support complement activation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 21, 109–114 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diepenhorst G. M., van Gulik T. M., Hack C. E. (2009) Complement-mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury: lessons learned from animal and clinical studies. Ann. Surg. 249, 889–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou W., Farrar C. A., Abe K., Pratt J. R., Marsh J. E., Wang Y., Stahl G. L., Sacks S. H. (2000) Predominant role for C5b-9 in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hart M. L., Ceonzo K. A., Shaffer L. A., Takahashi K., Rother R. P., Reenstra W. R., Buras J. A., Stahl G. L. (2005) Gastrointestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury is lectin complement pathway dependent without involving C1q. J. Immunol. 174, 6373–6380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walsh M. C., Bourcier T., Takahashi K., Shi L., Busche M. N., Rother R. P., Solomon S. D., Ezekowitz R. A., Stahl G. L. (2005) Mannose-binding lectin is a regulator of inflammation that accompanies myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. J. Immunol. 175, 541–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thurman J. M., Lucia M. S., Ljubanovic D., Holers V. M. (2005) Acute tubular necrosis is characterized by activation of the alternative pathway of complement. Kidney Int. 67, 524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thurman J. M., Royer P. A., Ljubanovic D., Dursun B., Lenderink A. M., Edelstein C. L., Holers V. M. (2006) Treatment with an inhibitory monoclonal antibody to mouse factor B protects mice from induction of apoptosis and renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 707–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thurman J. M., Ljubanovic D., Edelstein C. L., Gilkeson G. S., Holers V. M. (2003) Lack of a functional alternative complement pathway ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure in mice. J. Immunol. 170, 1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moller-Kristensen M., Wang W., Ruseva M., Thiel S., Nielsen S., Takahashi K., Shi L., Ezekowitz A., Jensenius J. C., Gadjeva M. (2005) Mannan-binding lectin recognizes structures on ischaemic reperfused mouse kidneys and is implicated in tissue injury. Scand. J. Immunol. 61, 426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Vries B., Walter S. J., Peutz-Kootstra C. J., Wolfs T. G., van Heurn L. W., Buurman W. A. (2004) The mannose-binding lectin-pathway is involved in complement activation in the course of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 1677–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Osthoff M., Katan M., Fluri F., Schuetz P., Bingisser R., Kappos L., Steck A. J., Engelter S. T., Mueller B., Christ-Crain M., Trendelenburg M. (2011) Mannose-binding lectin deficiency is associated with smaller infarction size and favorable outcome in ischemic stroke patients. PLoS ONE 6, e21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cervera A., Planas A. M., Justicia C., Urra X., Jensenius J. C., Torres F., Lozano F., Chamorro A. (2010) Genetically-defined deficiency of mannose-binding lectin is associated with protection after experimental stroke in mice and outcome in human stroke. PLoS ONE 5, e8433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan R. K., Ibrahim S. I., Takahashi K., Kwon E., McCormack M., Ezekowitz A., Carroll M. C., Moore F. D., Jr., Austen W. G., Jr. (2006) The differing roles of the classical and mannose-binding lectin complement pathways in the events following skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion. J. Immunol. 177, 8080–8085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jordan J. E., Montalto M. C., Stahl G. L. (2001) Inhibition of mannose-binding lectin reduces postischemic myocardial reperfusion injury. Circulation 104, 1413–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weiser M. R., Williams J. P., Moore F. D., Jr., Kobzik L., Ma M., Hechtman H. B., Carroll M. C. (1996) Reperfusion injury of ischemic skeletal muscle is mediated by natural antibody and complement. J. Exp. Med. 183, 2343–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams J. P., Pechet T. T., Weiser M. R., Reid R., Kobzik L., Moore F. D., Jr., Carroll M. C., Hechtman H. B. (1999) Intestinal reperfusion injury is mediated by IgM and complement. J. Appl. Physiol. 86, 938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang M., Alicot E. M., Chiu I., Li J., Verna N., Vorup-Jensen T., Kessler B., Shimaoka M., Chan R., Friend D., Mahmood U., Weissleder R., Moore F. D., Carroll M. C. (2006) Identification of the target self-antigens in reperfusion injury. J. Exp. Med. 203, 141–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McMullen M. E., Hart M. L., Walsh M. C., Buras J., Takahashi K., Stahl G. L. (2006) Mannose-binding lectin binds IgM to activate the lectin complement pathway in vitro and in vivo. Immunobiology 211, 759–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Busche M. N., Pavlov V., Takahashi K., Stahl G. L. (2009) Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury is dependent on both IgM and mannose-binding lectin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H1853–H1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang M., Takahashi K., Alicot E. M., Vorup-Jensen T., Kessler B., Thiel S., Jensenius J. C., Ezekowitz R. A., Moore F. D., Carroll M. C. (2006) Activation of the lectin pathway by natural IgM in a model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Immunol. 177, 4727–4734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirano M., Ma B. Y., Kawasaki N., Oka S., Kawasaki T. (2012) Role of interaction of mannan-binding protein with meprins at the initial step of complement activation in ischemia/reperfusion injury to mouse kidney. Glycobiology 22, 84–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwaeble W. J., Lynch N. J., Clark J. E., Marber M., Samani N. J., Ali Y. M., Dudler T., Parent B., Lhotta K., Wallis R., Farrar C. A., Sacks S., Lee H., Zhang M., Iwaki D., Takahashi M., Fujita T., Tedford C. E., Stover C. M. (2011) Targeting of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 confers protection from myocardial and gastrointestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 7523–7528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wessels M. R., Butko P., Ma M., Warren H. B., Lage A. L., Carroll M. C. (1995) Studies of group B streptococcal infection in mice deficient in complement component C3 or C4 demonstrate an essential role for complement in both innate and acquired immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92, 11490–11494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalina S. L., Mottram P. L. (1993) A microsurgical technique for renal transplantation in mice. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 63, 213–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wyss-Coray T., Yan F., Lin A. H., Lambris J. D., Alexander J. J., Quigg R. J., Masliah E. (2002) Prominent neurodegeneration and increased plaque formation in complement-inhibited Alzheimer's mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 10837–10842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stover C. M., Thiel S., Lynch N. J., Schwaeble W. J. (1999) The rat and mouse homologues of MASP-2 and MAp19, components of the lectin activation pathway of complement. J. Immunol. 163, 6848–6859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gal P., Harmat V., Kocsis A., Bian T., Barna L., Ambrus G., Vegh B., Balczer J., Sim R. B., Naray-Szabo G., Zavodszky P. (2005) A true autoactivating enzyme. Structural insight into mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 activations. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33435–33444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farrar C. A., Wang Y., Sacks S. H., Zhou W. (2004) Independent pathways of P-selectin and complement-mediated renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 133–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Selander B. (2006) Mannan-binding lectin activates C3 and the alternative complement pathway without involvement of C2. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1425–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peng Q., Li K., Smyth L. A., Xing G., Wang N., Meader L., Lu B., Sacks S. H., Zhou W. (2012) C3a and C5a promote renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1474–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lewis A. G., Kohl G., Ma Q., Devarajan P., Kohl J. (2008) Pharmacological targeting of C5a receptors during organ preservation improves kidney graft survival. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 153, 117–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zheng X., Zhang X., Feng B., Sun H., Suzuki M., Ichim T., Kubo N., Wong A., Min L. R., Budohn M. E., Garcia B., Jevnikar A. M., Min W. P. (2008) Gene silencing of complement C5a receptor using siRNA for preventing ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 973–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patel H., Smith R. A., Sacks S. H., Zhou W. (2006) Therapeutic strategy with a membrane-localizing complement regulator to increase the number of usable donor organs after prolonged cold storage. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 1102–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van der Pol P., Schlagwein N., van Gijlswijk D. J., Berger S. P., Roos A., Bajema I. M., de Boer H. C., de Fijter J. W., Stahl G. L., Daha M. R., van Kooten C. (2012) Mannan-binding lectin mediates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury independent of complement activation. Am. J. Transplant. 12, 877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park P., Haas M., Cunningham P. N., Alexander J. J., Bao L., Guthridge J. M., Kraus D. M., Holers V. M., Quigg R. J. (2001) Inhibiting the complement system does not reduce injury in renal ischemia reperfusion. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, 1383–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang M., Alicot E. M., Carroll M. C. (2008) Human natural IgM can induce ischemia/reperfusion injury in a murine intestinal model. Mol. Immunol. 45, 4036–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang M., Carroll M. C. (2007) Natural antibody mediated innate autoimmune response. Mol. Immunol. 44, 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.