Abstract

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is an autosomal dominant condition that is caused by abnormal synthesis of connective tissue. The syndrome classically affects the ocular, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular systems. The most common cardiovascular manifestations include mitral valve prolapse/regurgitation and aortic aneurysms at high risk of rupture and dissection. However, internal mammary artery (IMA) true aneurysms are rarely reported. In this case report, we describe a 43-year-old male patient with MFS and three previous thoracotomies referred for endovascular repair of bilateral IMA true aneurysms. To the best of our knowledge, there are no cases of endovascular treatment of bilateral IMA true aneurysms reported in the literature.

Keywords: Marfan syndrome, internal mammary artery aneurysm, wall graft stent, covered stent

A 43-year-old male patient with a history of Marfan syndrome (MFS), aortic and mitral valve replacement, and end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy requiring heart transplantation 4 years back initially presented to an outside hospital with a respiratory tract infection. As part of his evaluation, he had a chest computed tomography (CT) which incidentally revealed bilateral internal mammary artery (IMA) true aneurysms. He was subsequently referred to our institution for further evaluation.

A dedicated CT angiogram at our institution demonstrated a large, proximal right internal mammary artery (RIMA) aneurysm measuring 3.5 × 3.4 cm followed by a second aneurysm in the middle third of the RIMA measuring 2 × 2 cm. In addition, the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) showed a 9 mm focal aneurysmal dilatation at its origin with a bilobed aneurysm measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm proximally and 1.3 × 1.2 cm distally (Figs. 1 and 2A).

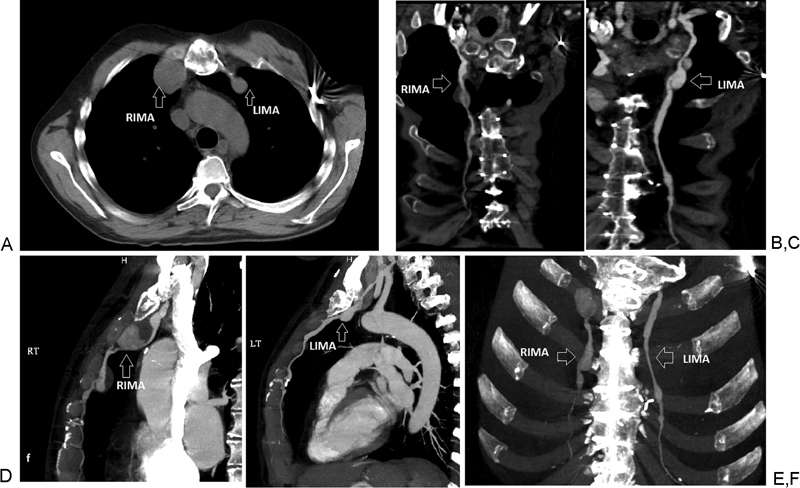

Fig. 1.

Chest computed tomographic angiogram showing: (A, B, D, F) RIMA large, proximal aneurysm (3.5 × 3.4 cm) followed by a second aneurysm in the middle third of the RIMA (2 × 2 cm). (A, C, E, F) LIMA focal aneurysmal dilatation at its origin (0.9 cm) followed by a bilobed aneurysm (1.5 × 1.5 cm proximally and 1.3 × 1.2 cm distally). LIMA, left internal mammary artery; RIMA, right internal mammary artery.

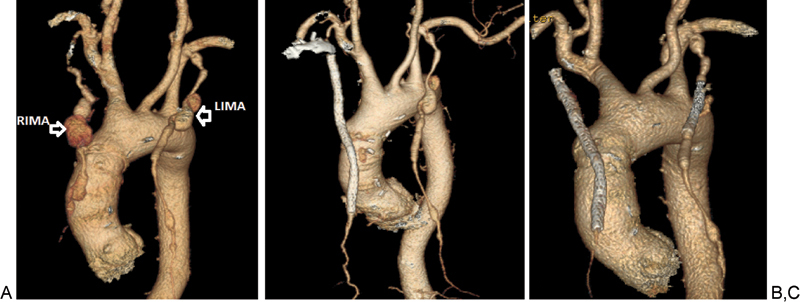

Fig. 2.

(A) Three-dimensional chest computed tomographic angiogram images showing RIMA and LIMA aneurysms. (B, C) Follow-up images after endovascular repair with endograft stents demonstrated complete resolution of the RIMA aneurysms (C) and marked decrease in size of the LIMA aneurysm. LIMA, left internal mammary artery; RIMA, right internal mammary artery.

Given the patient history of multiple thoracotomies, he was deemed to be a high-risk surgical candidate and referred for endovascular repair in September 2011.

The patient was brought to the cardiac catheterization laboratory where we first obtained 6 French (Fr) right brachial artery access and performed IMA angiography. With the JR 4 catheter engaged in the RIMA, we then wired the vessel with a 0.035" glidewire. Next, we used a glide catheter to help steer the glidewire past the aneurysms. This allowed us to position the glide catheter in the distal RIMA and to exchange our glidewire for a stiff 3-mm Amplatzer wire (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) We subsequently advanced a 7 Fr × 90 cm destination sheath just proximal to the more distal aneurysm. Finally, we delivered four sequential iCAST covered stents (Atrium, Hudson, New Hampshire), 5 × 59 mm, 6 × 22 mm, 7 × 59 mm, and 7 × 38 mm, successfully excluding the aneurysms (Fig. 3A, B).

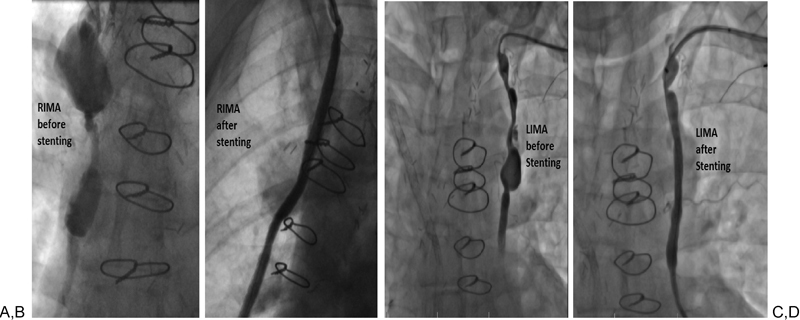

Fig. 3.

Angiogram of the right and left internal mammary artery aneurysms before (A, C) and after (B, D) endovascular repair. LIMA, left internal mammary artery; RIMA, right internal mammary artery.

One year later (December 2012), the patient was brought back to the catheterization laboratory to treat the enlarging LIMA aneurysm. We obtained 6 Fr left brachial artery access and used a similar strategy to position and deploy a 7 × 59 mm iCAST covered stent, delivered through a 7 Fr × 90 cm destination sheath, and we successfully excluded the LIMA aneurysm (Fig. 3C, D).

Follow-up CT angiogram, done in February 2013, demonstrated complete resolution of the RIMA aneurysm and marked decrease in size of the LIMA aneurysm (Fig. 2B, C).

Discussion

MFS is a common inherited connective tissue disorder with a reported incidence of 1 in 3,000 to 5,000 individuals.1 2 3

Genetically, most patients with MFS harbor mutations involving the Fibrillin-1 (FBN1) gene.4 In a minority of cases (less than 10%), an inactivating mutation in a gene encoding for transforming growth factor-β receptor 1 or 2 is responsible.5 6

These mutations cause abnormal synthesis, secretion, or accumulation of FBN1, which is an important microfibrillar component of elastic tissues. The resulting defective collagen and elastin formation causes cystic medial necrosis of the arteries with mucoid degeneration.7 This may lead to fragmentation and loss of tensile strength of the vessel fibers, allowing the vessel wall to stretch and form both aneurysms and dissection.8

Clinically, MFS manifests in many systems, including skeletal, ocular, nervous, and cardiovascular systems. Skeletal abnormalities include tall, thin, short torso, arachnodactyly, pectus deformities, hind foot valgus, disproportionately long extremities, scoliosis, and kyphosis. Ocular problems usually result from lens subluxation. Neurologic complications include dural ectasia, meningoceles, and postural headache.3 9

The cardiovascular manifestations, which account for most of the morbidity and mortality in MFS patient, include mitral valve regurgitation and/or prolapse, aortic root dilatation, ascending aortic, and abdominal aortic aneurysms with a high risk for dissection and rupture.10 11

To diagnose MFS, the 2010 revised Ghent Criteria 12 was established. This criteria utilizes the presence or absence of family history along with clinical and genetic characteristics. Without a family history of MFS, the presence of aortic dilatation/dissection with ectopia lentis, FBN1 mutation, or a systemic score ≥ 7 (see Table 1) is diagnostic of MFS. Also, the presence of ectopia lentis and FBN1 mutation together can be diagnostic.

Table 1. The 2010 revised Ghent nosology includes the following scoring system for systemic features12 .

| Wrist and thumb sign | 3 points (wrist or thumb sign: 1 point) |

| Pectus carinatum deformity | 2 (pectus excavatum or chest asymmetry: 1 point) |

| Hindfoot deformity | 2 points (plain pes planus: 1 point) |

| Pneumothorax | 2 points |

| Dural ectasia | 2 points |

| Protrusion acetabula | 2 points |

| Reduced upper segment/lower segment ratio (US/LS) and increased arm span/height and no severe scoliosis | 1 point |

| Scoliosis or thoracolumbar kyphosis | 1 point |

| Reduced elbow extension (≤ 170 degrees with full extension) | 1 point |

| Facial features (at least three of the following five features: dolichocephaly [reduced cephalic index or head width/length ratio], enophthalmos, downslanting palpebral fissures, malar hypoplasia, retrognathia) | 1 point |

| Skin striae | 1 point |

| Myopia > 3 D | 1 point |

| Mitral valve prolapse (all types) | 1 point |

| Myopia >3 D | 1 point |

Note: A systemic score ≥7 indicates systemic involvement.

Whereas in patients with a family history of MFS, the presence of either aortic dilatation/dissection, ectopia lentis, or a systemic score ≥ 7 points will be enough to make the diagnosis.

Besides aortic aneurysms, peripheral true aneurysms were also reported in association with connective tissue disorders (such as MFS, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome,13 type I neurofibromatosis, and fibromuscular dysplasia), vasculitis (such as Kawasaki disease,14 polyarteritis nodosa,15 and systemic lupus erythematosus), and atherosclerosis. However, IMAs are rarely affected with only two case reports in the literature16 17 describing true aneurysms of the IMA as a manifestation of MFS.

The diagnosis of IMA aneurysm is usually based on incidental finding of “coin lesion” on simple chest X-ray or anterior mediastinal mass seen on chest CT scan with or without contrast. Few cases in the literature reported ruptured aneurysms causing spontaneous hemothorax and, rarely, hemoptysis.13 18

While no published guidelines exist, the decision to treat IMA aneurysms is based on the size, the presence of symptoms, and the risk for impending rupture. Traditionally, true IMA aneurysms have been managed by open surgical resection or ligation. However, open surgical repair has significant risks including bleeding, incision site infection, and injury to nearby structures.

Endovascular techniques, on the contrary, have lower risk for the earlier mentioned complications, shorter hospital stay, and may be advantageous for MFS, because patients with various types of cystic medial necrosis have suboptimal outcomes with open repair.17

To the best of our knowledge, no previous case reports exist of endovascular repair of bilateral true IMA aneurysms in the literature. Our patient's IMA aneurysms were treated successfully via an endovascular approach using iCAST covered stents (balloon-expandable stainless steel stents that are fully encapsulated in two layers of polytetrafluoroethylene). The follow-up CT angiogram demonstrated complete resolution.

Conclusion

IMA aneurysms are rare in patients with MS, and bilateral endovascular repair of IMA aneurysms, to the best of our knowledge, has not previously been reported in literature. These aneurysms can potentially be morbid, depending on symptoms and the rate of growth. Endovascular repair of these aneurysms using covered stents is feasible and may be advantageous over open surgical options in selected patients.

References

- 1.Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Rijlaarsdam M E, Scholte A J. et al. The clinical spectrum of missense mutations of the first aspartic acid of cbEGF-like domains in fibrillin-1 including a recessive family. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(12):E1915–E1927. doi: 10.1002/humu.21372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez F, Godfrey M, Lee B, New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1995. Marfan syndrome and related disorders; p. 4079. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judge D P, Dietz H C. Marfan's syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366(9501):1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakai L Y, Keene D R, Glanville R W, Bächinger H P. Purification and partial characterization of fibrillin, a cysteine-rich structural component of connective tissue microfibrils. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(22):14763–14770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhurst R J. TGF beta signaling in health and disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):790–792. doi: 10.1038/ng0804-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuguchi T, Collod-Beroud G, Akiyama T. et al. Heterozygous TGFBR2 mutations in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):855–860. doi: 10.1038/ng1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz H C, Ramirez F, Sakai L Y. Marfan's syndrome and other microfibrillar diseases. Adv Hum Genet. 1994;22:153–186. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9062-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunton T E, Biery N J, Myers L, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Dietz H C. Phenotypic alteration of vascular smooth muscle cells precedes elastolysis in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Circ Res. 2001;88(1):37–43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen P R, Schneiderman P. Clinical manifestations of the Marfan syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28(5):291–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams J N, Trent R J. Aortic complications of Marfan's syndrome. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1722–1723. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prockop D J, Czarny-Ratajczak M. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008. Heritable disorders of the connective tissue; pp. 2461–2469. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeys B L, Dietz H C, Braverman A C. et al. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47(7):476–485. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phan T G, Sakulsaengprapha A, Wilson M, Wing R. Ruptured internal mammary artery aneurysm presenting as massive spontaneous haemothorax in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Aust N Z J Med. 1998;28(2):210–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1998.tb02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiwata S, Nishiyama S, Nakanishi S. et al. Coronary artery disease and internal mammary artery aneurysms in a young woman: possible sequelae of Kawasaki disease. Am Heart J. 1990;120(1):213–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90184-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giles J A, Sechtin A G, Waybill M M, Moser R P Jr. Bilateral internal mammary artery aneurysms: a previously unreported cause for an anterior mediastinal mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154(6):1189–1190. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.6.2110725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Common A A, Pressacco J, Wilson J K. Internal mammary artery aneurysm in Marfan syndrome: case report. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1999;50(1):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose J F, Lucas L C, Bui T D, Mills J L Sr. Endovascular treatment of ruptured axillary and large internal mammary artery aneurysms in a patient with Marfan syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(2):478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S J, Kim C W, Kim S. et al. Endovascular treatment of a ruptured internal thoracic artery pseudoaneurysm presenting as a massive hemothorax in a patient with type I neurofibromatosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28(6):818–821. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]