Abstract

A case of ergotism is presented to illustrate the role of duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of this nonatherosclerotic cause of peripheral arterial disease. Historical aspects of ergotism are discussed together with reference to the relative vulnerability of different segments of the arterial circulation. Our case emphasizes the potential for complete reversibility of the vascular changes if recognized early.

Keywords: ergotism, ergot alkaloids, Claviceps purpurea, nonatherosclerotic arterial disease, lower limb ischemia, migraine, duplex ultrasound

The vast majority of patients with peripheral arterial disease have atherosclerosis. A small number are caused by thrombotic disorders, thromboembolism, or inflammatory arterial diseases. Even rarer, with an incidence rate of 0.001 to 0.002%1 is ergotism occurring in patients who take ergotamine preparations for recurrent headaches. Ergotism is a potentially reversible disease process which needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with peripheral lower limb ischemia especially if there is a lack of classical risk factors for atherosclerosis. This case presentation and review of the literature aims to grasp the complexity of this rare disease process as well as demonstrating the pivotal role of duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of patients who are affected by ergotism.

Case Report

A 38-year-old female patient presented with a 12-month history of classical severe lower limb symptoms of intermittent claudication. Her medical history was unremarkable and notable for absence of classical risk factors for atherosclerosis; she was fit and healthy with normal blood pressure and heart rate recordings, and there was no history of diabetes, smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. However, the patient did have a long history of migraine, which had been treated with both caffeine–ergotamine tartrate and methysergide.

On clinical examination, the common femoral artery pulses were reduced bilaterally and accompanied by bruits. She was referred to a specialized vascular laboratory for duplex ultrasound study of the abdominal aorta, iliac, and femoral arteries.

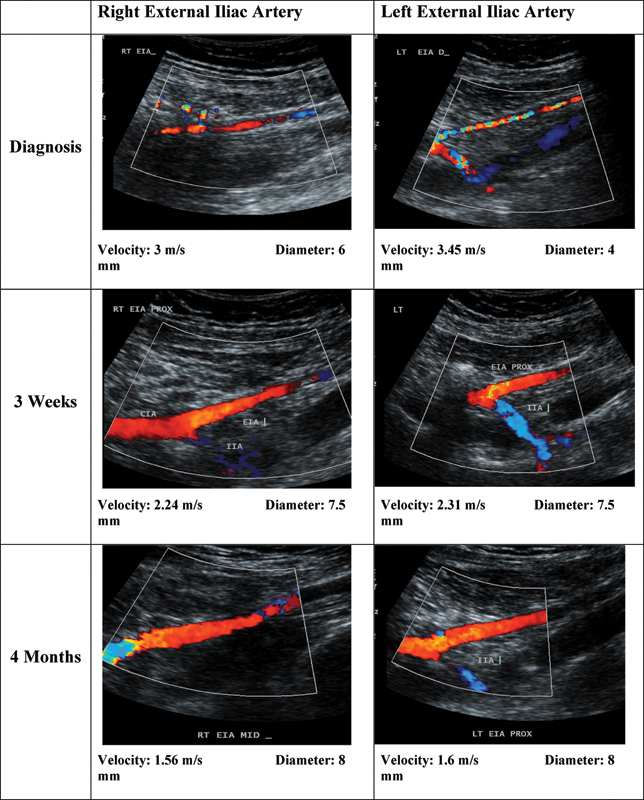

The duplex ultrasound study demonstrated smooth, concentric luminal narrowing of the external iliac arteries, with increased blood flow velocities of 3 m/s on the right and 3.5 m/s on the left which indicated a 50 to 75% and > 75% stenosis, respectively. In addition, luminal diameters were recorded at 6 mm on the right and 4 mm on the left (normal, ∼7–8 mm). There was no accompanying calcification or other evidence of an atherosclerotic process. The abdominal aorta appeared normal.

The results of the duplex ultrasound study strongly suggested a nonatherosclerotic cause, and given the patients' medical history, the possibility of ergotism. The patient was instructed to cease all migraine medication and both aspirin and a calcium channel blocker were prescribed to prevent any thrombotic complications and to promote vasodilation.

A repeat duplex ultrasound study of the abdominal aorta, iliac, and lower limb arteries were performed at 3 weeks and again at 4 months after diagnosis. At 3 weeks, there was a significant improvement in the diameter of the affected segments. At 4 months, the external iliac arteries had returned to normal luminal diameter, with normal arterial blood flow velocities. There were no residual symptoms. This complete recovery without any other intervention confirmed the diagnosis of ergotism.

The patient had no residual symptoms of intermittent claudication as the cessation of the migraine medication is not requiring any treatment for migraine at the present (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Color Doppler images of the right and left external iliac arteries over 4-month time frame.

Discussion

Ergot is the more common name of the sclerotia of a fungal species, from within the genus of Claviceps purpurea, which produces ergot alkaloids. Ergotism occurs when either the fungus is ingested via the contamination of grain, for example, rye, or by the medicinal use of drugs derived from ergotamine compounds.2 3 An epidemic of ergotism (St. Anthony fire) occurred in medieval times as a consequence of this fungal contamination in grain. In recent times, medications containing ergot alkaloids have been used in the treatment of migraine, vascular headaches, and control of postpartum hemorrhage.

Some of the earliest documented medicinal uses of ergot preparations were for childbirth. There is documented evidence from as early as the 1500s that ergot derivatives were used to accelerate labor, prevent postpartum hemorrhage, and in some cases to induce abortion in the early stages of pregnancy4 5 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ergot of rye, the sclerotium.4

The major pharmacological effects of ergot alkaloids and their direct derivatives are stimulation of α-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells, resulting in vasoconstriction. In addition, an important potential consequence of intense protracted vasospasm is the loss of endothelial integrity and thereby increased risk of thrombosis and irreversible ischemia. Furthermore, loss of the endothelium exposes the unprotected vascular smooth muscle to circulating catecholamines and other vasoactive amines and autacoids. There is also the risk of fibrosis of the vessel wall secondary to constriction of the vasa vasora.6 7 8 9

Ergot alkaloids are primarily metabolized by the liver and specifically by a subgroup of the cytochrome P-450 isoenzyme CYP3A4, and are excreted in the feces via biliary elimination with a small fraction excreted through the kidneys. There is an increase in the potential for ergotism when a patient is using other drugs that are also metabolized by the liver, such as antibiotics, oral contraceptives and antiviral medication, such as protease inhibitors and there is also an increased risk of ischemia with the combination of β-blockers and ergot alkaloids due to the inhibition of β2 receptor–mediated vasodilation at the level of the vascular smooth muscle cells.10 Smoking and caffeine also increase the risk of ergotism.9

The formulation most associated with medicinal-induced ergotism is the ergotamine–caffeine suppository. Ergot alkaloids are poorly absorbed orally (< 2%), however, absorption via the rectum is considered to be more complete. Rectal absorption is directed toward the liver, and with the addition of caffeine, ergotamine metabolism is inhibited.

Arterial vasospasm or vasoconstriction resulting from ergot consumption can affect any blood vessel in the body, however, the lower limbs are most commonly affected.5 Direct involvement of the peripheral arterial circulations by acute ergotism can cause symptoms of intermittent claudication, limb ischemia, and Raynaud phenomenon.8 11 12 13 14 Involvement of the coronary arteries can cause angina and myocardial infarction.4 15 16 Involvement of the extracranial vessels and retinal arteries can cause neurological complications and loss of vision,17 18 19 20 and involvement of the visceral arteries can result in visceral ischemia and renovascular complications.9 21 22 23 24

The direct vasoconstrictive effect that is associated with ergotism curiously targets medium-sized vessels, notably the external iliac artery and the superficial femoral artery.5 9 Could the substructure of the arterial wall predispose to the selectivity of arterial involvement in ergotism? Considering the arterial wall, the question arises as to whether the ratio of collagen to elastin or the ratio of vascular smooth muscle to connective tissue is a factor in the specific selection of these arteries in regards to ergotism.

The ratio of collagen to elastin within the arterial wall has been used to determine the relative distensibility of an artery for the maintenance of tension within an arterial wall. The lowest collagen-to-elastin ratio is found in the proximal lower limb arteries.25 This unique substructure could be a predisposition to the selective involvement of this segment of the arterial circulation to the vasoconstrictive effects of ergot.

In addition, it has been documented that elastic arteries are known to distribute drugs more efficiently. An elastic artery may take up more drug than muscular arteries. Experiments show that the drugs metabolized by the liver will preferentially localize within the elastin sheath thereby creating locally high concentrations of the drug.26

If endothelial integrity is lost under circumstances of protracted vasoconstriction there will be loss of protection for the vascular smooth muscle and hence the potential for relapse especially during the early phase of recovery.

Ergotism is a reversible condition. Therefore, if diagnosed and treated quickly, irreversible ischemia can be avoided. Management therefore involves discontinuation of the ergot and other potential vasoconstrictors, and the use of vasodilators, anticoagulants, and consideration of endovascular procedures. As with our patient, we would routinely recommend antithrombotic prophylaxis because of the increased risk of arterial thrombotic complications predisposed by the vessel wall spasm and endothelial injury.

Peripheral balloon angioplasty and other interventions may be indicated; however, vascular injury is a potential complication of any invasive procedure under these circumstances. Furthermore, intervention by angioplasty in the acute phase would be expected to fail because clinical experience indicates that there is an increased risk of recurrent spasm of the affected arterial segments during the acute phase of ergotism.

Conclusion

In this case, duplex ultrasonography was the diagnostic imaging modality with serial ultrasound studies directing ongoing management and enabling close surveillance of the vascular status.

This case highlights specific findings seen with this disease process using duplex ultrasonography. There is selective involvement of the external iliac arteries with segmental and smooth concentric vasoconstriction and other features of a nonatherosclerotic process, including the absence of calcification. The reversibility of ergotism is confirmed; however, there is the potential for relapse related to the loss of endothelial integrity. This could also predispose to thrombotic complications.

Both the noninvasive nature and the absence of radiation exposure for the patient and the technician make duplex ultrasonography the preferred imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis and management of nonatherosclerotic vascular disorders such as ergotism.

References

- 1.Tribble M A, Gregg C R, Margolis D M, Amirkhan R, Smith J W. Fatal ergotism induced by an HIV protease inhibitor. Headache. 2002;42(7):694–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enge I, Sivertssen E. Ergotism due to therapeutic doses of ergotamine tartrate. Am Heart J. 1965;70(5):665–670. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(65)90395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelbessa U, Asfaw D, Yeshi W, Agata N, Abebe B, Wubalem Z. Laboratory studies on the outbreak of Gangrenous Ergotism associated with consumption of contaminated barley in Arsi, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2002;16(3):317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M R. The history of ergot of rye (Claviceps purpurea) I: from antiquity to 1900. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39(2):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff P L. Ergot and its alkaloids. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):98. doi: 10.5688/aj700598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin Z K, Ceraldi C C. Ergotism associated with HIV antiviral protease inhibitor therapy. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(3):676–678. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia G D, Goff J M Jr, Hadro N C, O'donnell S D, Greatorex P S. Chronic ergot toxicity: A rare cause of lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(6):1245–1247. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.105668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merhoff G C, Porter J M. Ergot intoxication: historical review and description of unusual clinical manifestations. Ann Surg. 1974;180(5):773–779. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197411000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zavaleta E G, Fernandez B B, Grove M K, Kaye M D. St. Anthony's fire (ergotamine induced leg ischemia)—a case report and review of the literature. Angiology. 2001;52(5):349–356. doi: 10.1177/000331970105200509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cagatay A, Guler O, Guven K. Ergotism caused by concurrent use of ritonavir and ergot alkaloids: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109(5):639–640. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagby R J, Cooper R D. Angiography in ergotism. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1972;116(1):179–186. doi: 10.2214/ajr.116.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagerberg S, Jorulf H, Sandberg C G. Ergotism, arteriospastic disease and recovery, studied angiographically. Acta Med Scand. 1967;182(6):769–772. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1967.tb10905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venter C P, Joubert P H, Buys A C. Severe peripheral ischaemia during concomitant use of beta blockers and ergot alkaloids. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289(6440):288–289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6440.288-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver R, Phillips M, Vacek J L. St. Anthony's fire: a medieval disease in modern times: case history. Angiology. 1989;40(10):929–932. doi: 10.1177/000331978904001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldfisher J D. Acute myocardial infarction secondary to ergot therapy. N Engl J Med. 1960;262:860–863. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathey D, Montz R, Hanrath P, Kuck K H, Bleifeld W. Noninvasive method for recognition of coronary artery spasm: 201thallium sequential scintigraphy of themyocardium after ergotamine provocation (author's translation). (in English) Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1980;105(15):509–515. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1070697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne-Quinn E. Arteriospasm after overdose of oral ergotamine tartrate in migraine. BMJ. 1964;2(5408):552–553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5408.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellison A BC. Ergot intoxication in a young woman with migraine (case report) W V Med J. 1960;56:376–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarides M K, Karageorgiou C, Tsiara S, Grillia M, Dayantas J N. Severe facial ischaemia caused by ergotism. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1992;33(3):383–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richter A M, Banker V P. Carotid ergotism. A complication of migraine therapy. Radiology. 1973;106(2):339–340. doi: 10.1148/106.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedotin M S, Hartman C. Ergotamine poisoning producing renal arterial spasm. N Engl J Med. 1970;283(10):518–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197009032831006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene F L, Ariyan S, Stansel H C Jr. Mesenteric and peripheral vascular ischemia secondary to ergotism. Surgery. 1977;81(2):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemingway D L Ergot poisoning with multisystem involvement Mil Med 1965. Nov130111103–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demir S, Akin S, Tercan F, Ariboğan A, Oğuzkurt L. Ergotamine-induced lower extremity arterial vasospasm presenting as acute limb ischemia. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16(2):165–167. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1931-08.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer G M, Llaurado J G. Collagen and elastin content in canine arteries selected from functionally different vascular beds. Circ Res. 1966;19(2):394–399. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang C W, Edelman E R. Arterial ultrastructure influences transport of locally delivered drugs. Circ Res. 2002;90(7):826–832. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000016672.26000.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]