Abstract

Phosphorylation of the cell adhesion protein CEACAM1 increases insulin sensitivity and decreases insulin-dependent mitogenesis in vivo. Here we show that CEACAM1 is a substrate of the EGFR and that upon being phosphorylated, CEACAM1 reduces EGFR-mediated growth of transfected Cos-7 and MCF-7 cells in response to EGF. Using transgenic mice overexpressing a phosphorylation-defective CEACAM1 mutant in liver (L-SACC1), we show that the effect of CEACAM1 on EGF-dependent cell proliferation is mediated by its ability to bind to and sequester Shc, thus uncoupling EGFR signaling from the ras/MAPK pathway. In L-SACC1 mice, we also show that impaired CEACAM1 phosphorylation leads to ligand-independent increase of EGFR-mediated cell proliferation. This appears to be secondary to visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome, with increased levels of output of free fatty acids and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor from the adipose tissue of the mice. Thus, L-SACC1 mice provide a model for the mechanistic link between increased cell proliferation in states of impaired metabolism and visceral obesity.

Introduction

Activation of the tyrosine kinase of EGFR by EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), and other ligands causes EGFR to phosphorylate itself and other substrates. This activates signaling pathways that regulate cell growth, proliferation, and apoptosis, including the ras/MAPK mitogenic pathway, which is coupled to EGFR by Grb2 directly or indirectly through Shc (1, 2), the PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway, and others (3).

Carcinoembryonic antigen–related (CEA-related) cell adhesion molecule (CEACAM1) is a transmembrane glycoprotein in endothelial cells, B cells, interleukin-activated T cells, and epithelial cells (4, 5). CEACAM1 is a substrate of the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in liver, but not in muscle and fat tissue. It is expressed as two spliced variants differing by the inclusion (CEACAM1-4L) or exclusion (CEACAM1-4S) of most of its cytoplasmic tail, including all phosphorylation sites (6). Rat CEACAM1-4L is phosphorylated on Tyr488 by the insulin receptor (7). This phosphorylation requires an intact Ser503 residue in its cytoplasmic tail. The primary structure of CEACAM1-4L is markedly conserved among species, with the DDVxY488 tyrosine phosphorylation motif and the RPTS503A cAMP-dependent serine kinase target site being conserved. As predicted, we have thus observed similar phosphorylation properties of this protein in human, mouse, and rat (7–9).

CEACAM1-4L levels are downregulated in prostate, breast, colon, and hepatocellular carcinomas (10–14), resulting from aberrant chromatin acetylation in some tumors (15). Moreover, re-introducing CEACAM1-4L in these epithelial cells reduces their tumorigenicity (16–19). Additionally, CEACAM1-4L expression decreases cell growth in response to insulin (20, 21). This implicates CEACAM1-4L in tumor suppression and the regulation of a normal epithelial cell phenotype and proliferation (22). The mechanism underlying the tumor suppression function of CEACAM1-4L remains largely unknown, but it appears to depend on the phosphorylation state of CEACAM1-4L (4, 23).

CEACAM1-4L also downregulates cell growth in response to insulin in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (20, 21). Upon phosphorylation by the insulin receptor, CEACAM1-4L binds to and sequesters Shc. This downregulates the ras/MAPK mitogenic pathway and, by enhancement the ability of Shc to compete with insulin receptor substrate–1 for phosphorylation, downregulates the PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway that mediates cell proliferation and survival (21). Because EGFR signaling increases more commonly than that of the insulin receptor in advanced cancers of epithelial tissues (24), we investigated whether CEACAM1-4L is also a substrate of EGFR and whether it decreases cell growth in response to EGF.

Recent data from our laboratory indicate that CEACAM1-4L regulates insulin sensitivity by promoting insulin clearance in liver (9). It exerts this effect by undergoing internalization as part of the receptor-mediated insulin endocytosis complex and increasing its cellular uptake via clathrin-coated vesicles (25–28). Transgenic mice with liver-specific overexpression of the phosphorylation-defective S503A CEACAM1-4L mutant (L-SACC1) develop impaired insulin clearance, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and increased visceral obesity (9). Manifestations of insulin resistance include elevated levels of plasma FFAs and triglycerides.

Fasting plasma FFAs are commonly elevated in individuals with obesity (29). Whether visceral obesity develops as a result of increased insulin release to compensate for insulin resistance, as in the L-SACC1 mouse, or as a result of increased intake of high-fat diet, FFAs play a significant role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance (30–32). Thus, visceral obesity is a major determinant of insulin action.

Mounting evidence indicates that visceral obesity increases the death rate from common cancers, including those of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, breast, and ovary (33, 34). The high content of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the Western diet has been implicated in this process (35, 36). However, the mechanism linking altered metabolic to mitogenic pathways is not completely understood (37). It may involve activation of EGFR by fatty acids, independently of EGF (38–42).

There is emerging evidence that the adipose tissue acts as an endocrine organ, releasing many modulators of metabolism and cell growth into the circulation. In addition to FFAs (43, 44), the adipose tissue in obese individuals releases HB-EGF into the portal circulation (45). Both FFAs and HB-EGF activate the tyrosine kinase of EGFR in epithelial cells. Thus, these adipokines may act as the unifying mechanisms of increased visceral obesity and altered mitogenesis. Given the important role of CEACAM1-4L in the regulation of visceral obesity and tumorigenesis, we used the L-SACC1 mouse to investigate whether CEACAM1-4L constitutes a molecular link between metabolism and growth.

Results

CEACAM1-4L is a substrate of EGFR.

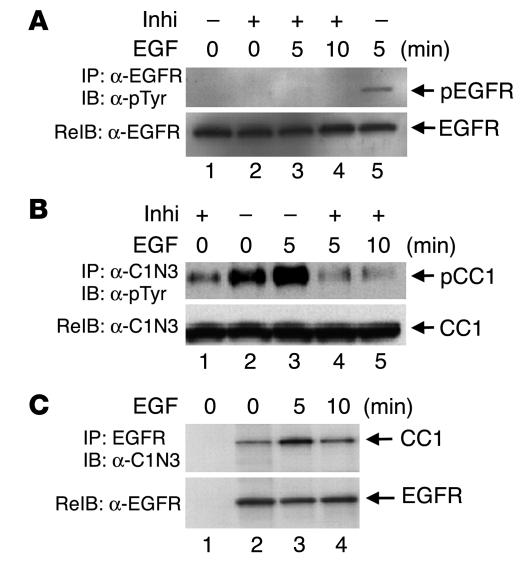

Because EGF stimulates phosphorylation of CEACAM1-4L by EGFR in cell-free systems (46), we examined whether EGFR phosphorylates CEACAM1-4L in response to EGF in intact HT29p human colon cancer cells that express only CEACAM1-4L of the CEA proteins (47). Serum-starved cells were subjected to treatment with buffer alone (Figure 1A, 0-minute lanes) or EGF (Figure 1A, 5- and 10-minute lanes) for 5–10 minutes as indicated. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with PD168393, an EGFR inhibitor, prior to EGF or buffer treatment (Figure 1A, + Inhi lanes). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with α-EGFR (Figure 1A) and an antibody against human pancreatic CEACAM (α-C1N3; Figure 1B) prior to immunoblotting with α-phosphotyrosine (α-pTyr) for the detection of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. To normalize for the amount of proteins in the immunoprecipitates, we reprobed proteins with α-EGFR (Figure 1A) and α-C1N3 (Figure 1B), respectively. As Figure 1 reveals, EGF stimulation of cells for 5 minutes significantly increased phosphorylation of EGFR (Figure 1A, lane 5 versus lane 1) and CEACAM1-4L (Figure 1B, lane 3 versus lane 2) when PD168393 was not added. As expected, the addition of PD168393 blunted EGFR phosphorylation in response to EGF (Figure 1A, lane 3 versus lane 5). This in turn reduced CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation significantly both in the presence (Figure 1B, lane 4 versus lane 3) and (Figure 1B, lane 1 versus lane 2) absence of EGF. The data indicate that EGF specifically increases CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation by EGFR in these cells.

Figure 1.

EGF induces CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation by EGFR in intact HT29p human colon cancer cells. Serum-starved HT29p cells were treated with buffer alone (_) or with the EGFR inhibitor PD168393 (Inhi; +) for 1 hour prior to treatment with EGF (100 nM) for 0_10 minutes. Equal amounts (100 μg) of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with α-EGFR (A) or α-C1N3 (B) prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (IB) with α-pTyr for detection of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins (pEGFR and pCC1) and re-immunoprobing (ReIB) with α-EGFR and α-C1N3 to account for the amount of these proteins in the immunoprecipitates. For examination of the CEACAM1-4L/EGFR association, 100 μg of cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with α-EGFR and immunoblotted with α-C1N3 (C, lanes 2_4). To account for nonspecific binding of proteins to agarose, equal amounts of proteins were incubated without the addition of antibody (C, lane 1). The results obtained were consistent in at least three experiments.

Next we carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments to examine the CEACAM1-4L/EGFR interaction. To this end, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with α-EGFR prior to analysis by electrophoresis and immunoprobing with α-C1N3 (Figure 1C, lanes 2–4). Additionally, equal amounts of proteins were incubated with agarose in the absence of antibodies for the examination of nonspecific binding to agarose (Figure 1C, lane 1). Normalization for the amount of EGFR in the immunoprecipitate (Figure 1C, lower panel) revealed that EGF treatment for 5 minutes increased the amount of CEACAM1-4L in the EGFR immunoprecipitate (Figure 1C, lane 3 versus lane 2). However, prolonged treatment with EGF did not significantly increase the association between CEACAM1-4L and EGFR (Figure 1C, lane 4 versus lane 2).

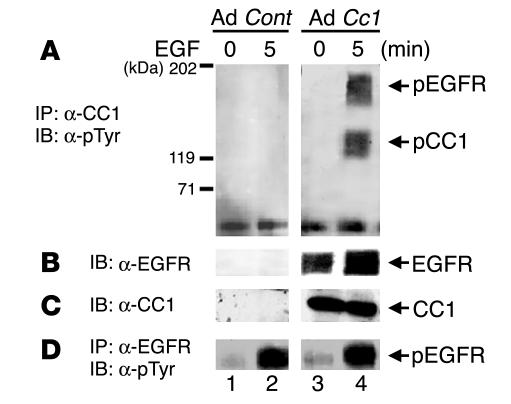

Because α-C1N3 cross-reacts with other members of CEA family, we reexamined CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation by EGFR in MDA-MB468 human breast cancer cells that had been infected with an adenovirus vector containing cDNA encoding CEACAM1-4L (Ad Cc1; Figure 2, lanes 3 and 4) or an adenovirus control (Ad Cont; Figure 2, lanes 1 and 2). At 48 hours after infection, cells were treated with EGF, and proteins were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal α–rat CEACAM1-4L (α-CC1; Figure 2A) or α-EGFR (Figure 2D) prior to Western blot analysis with α-pTyr. After normalization for the amount of protein (Figure 2C), CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation was more notable in response to EGF than in its absence (Figure 2A, lane 4 versus lane 3) in Ad Cc1–infected cells, while no band was detected in cells infected with Ad Cont (Figure 2A, lanes 1 and 2). Moreover, reprobing with α-EGFR revealed higher co-immunoprecipitation between EGFR and CEACAM1-4L by about 2-fold in the presence of EGF compared with buffer alone (Figure 2B, lane 4 versus lane 3). Taken together, the data reveal that CEACAM1-4L is phosphorylated by EGFR in response to EGF and that its phosphorylation increases its association with EGFR. The data, however, do not rule out the possibility that the CEACAM1-4L/EGFR interaction may be indirect.

Figure 2.

EGFR phosphorylates CEACAM1-4L in infected human MDA-MB468 breast cancer cells. MDA-MB468 breast cancer cells were infected with Ad Cc1 (lanes 3 and 4) or with Ad Cont (lanes 1 and 2) prior to EGF treatment. Equal amounts of proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-CC1 (A) or α-EGFR (D) prior to Western blot analysis with α-pTyr. (B) Proteins in A were reprobed with α-EGFR. (C) To account for the amount of CEACAM1-4L, amounts of proteins equal to those in A were applied on the same SDS-PAGE gel and were immunoblotted with α-CC1. The results obtained were consistent in at least 3 experiments.

CEACAM1-4L is not directly associated with EGFR.

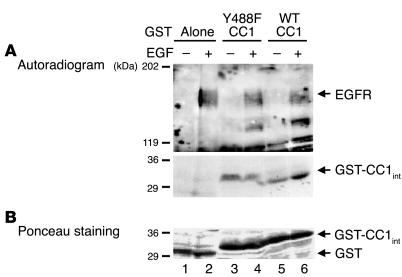

To examine whether EGFR phosphorylates CEACAM1-4L directly, we subjected MDA-MB468 cells to treatment with buffer alone (Figure 3, – lanes) or 100 nM EGF (Figure 3, + lanes) for 5 minutes prior to lysis and immunoprecipitation of 150 μg of cell lysates with α-EGFR. The immunoprecipitates were then incubated with 150 μg each of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) alone (Figure 3, lanes 1 and 2) or a fusion of GST with WT and Y488F peptides derived from the cytoplasmic tail of CEACAM1-4L (GST–WT CEACAM1-4L and GST–Y488F CEACAM1-4L; Figure 3, lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 3 and 4, respectively) (7) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphorylated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography (Figure 3A) and Ponceau S staining to correct for the amount of GST peptide in the reaction mixture (Figure 3B). As Figure 3A reveals, EGFR activation and phosphorylation was associated with increased phosphorylation of GST–WT CEACAM1-4L (Figure 3A, lane 6 versus lane 5) but not the GST–Y488F CEACAM1-4L mutant (Figure 3A, lane 4 versus lane 3) or GST controls (Figure 3A, lane 2 versus lane 1). This demonstrates that CEACAM1-4L is a direct substrate of EGFR and that its phosphorylation by EGFR occurs at Tyr488.

Figure 3.

CEACAM1-4L is a direct substrate of EGFR. (A) After treatment of MDA-MB468 cells with EGF (100 nM) (+) or buffer alone (_) for 5 minutes, cells were lysed and EGFR was extracted by immunoprecipitation with α-EGFR. GST fusion to intracellular peptides of wild type (WT CC1; lanes 5 and 6) or Y488F mutant (Y488F CC1; lanes 3 and 4) CEACAM1-4L (GST-CC1int) were incubated with equal amounts of EGFR immunoprecipitates in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for 10 minutes prior to the addition of SDS buffer and analysis by 6_12% SDS-PAGE and autoradiography for the detection of phosphorylated proteins. Peptide-free GST was included as control to account for nonspecific association (Alone; lanes 1 and 2). (B) The amount of GST peptides from the experiment in A, measured by Ponceau S staining. The results obtained were consistent in at least three experiments. The two gels in A are from the same SDS-PAGE gel and differ in the exposure time of the autoradiogram for optimal visualization of both EGFR and GST bands.

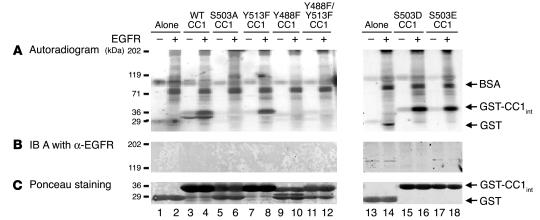

In order to determine whether CEACAM1-4L directly associates with EGFR, we performed GST pull-down assays in which we phosphorylated GST fusion peptides from WT and mutant CEACAM1-4L (7) precoupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads by EGFR in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphorylated proteins were analyzed by autoradiography (Figure 4A) and Ponceau S staining (Figure 4C). As Figure 4 reveals, EGFR increased phosphorylation of WT and Y513F CEACAM1-4L (Figure 4A, lane 4 versus lane 3 and lane 8 versus lane 7, respectively). In contrast, EGFR did not phosphorylate CEACAM1-4L fusion peptides in which Tyr488 was replaced with Phe either individually or together with Tyr513 (Figure 4A, lane 10 versus lane 9 and lane 12 versus lane 11, respectively). Similarly, mutation of Ser503 to Ala abolished CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation by EGFR (Figure 4A, lane 6 versus lane 5). Mutation of Ser503 to the Asp or Glu residue did not adversely affect CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation by EGFR (Figure 4A, lane 16 versus lane 15 and lane 18 versus lane 17, respectively). Taken together the data suggest that CEACAM1-4L is directly phosphorylated by EGFR on Tyr488 and that this phosphorylation requires prior Ser503 phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

CEACAM1-4L does not directly interact with EGFR. (A) Sepharose-coupled GST fusion to intracellular peptides of WT (lanes 3 and 4) or mutant (lanes 5_12 and 15_18) CEACAM1-4L were incubated with (+) or without (_) purified EGFR in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Peptide-free GST was included as control to account for nonspecific association (lanes 1, 2, 13, and 14). After protein binding, the Sepharose pellets were analyzed by 6_12% SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Proteins in A were immunoblotted with α-EGFR for examination of the association of EGFR with CEACAM1-4L. (C) The amount of GST peptides from the experiment in A was measured by Ponceau S staining. The results obtained were consistent in at least three experiments.

Immunoblots of proteins using α-EGFR did not detect EGFR in the GST–CEACAM1-4L pellets (Figure 4B). This suggests that the interaction between these two proteins (Figure 1C) is indirect, as is the case for CEACAM1-4L/insulin receptor interaction (27).

CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation downregulates the mitogenic action of EGF.

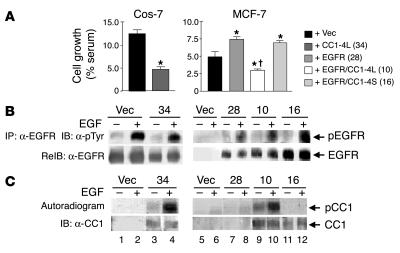

Next, we investigated whether CEACAM1-4L downregulates the mitogenic effect of EGF, as it does with insulin (20, 21). To this end, we stably transfected MCF-7 and Cos-7 cells with Ceacam1 cDNA prior to determining cell growth in clonal pairs (with or without CEACAM1-4L) expressing comparable number of receptors per cell (Figure 5A). Cell growth in response to EGF was correlated with phosphorylation of EGFR (Figure 5B) and CEACAM1-4L (Figure 5C) in the presence or absence of EGF. As determined by immunoblotting of EGFR immunoprecipitates with α-pTyr and after normalizing for the amount of EGFR in the pellets by re-immunoblotting (Figure 5B), EGF treatment activated EGFR in all clones examined (Figure 5B, + versus – lanes), except in MCF-7 cells transfected with vector alone (Figure 5B, lane 6 versus lane 5). Expression of CEACAM1-4L, which undergoes phosphorylation in response to EGF (Figure 5C, lane 4 versus lane 3), significantly reduced growth of Cos-7 cells (Figure 5A, 4.67% ± 0.60% serum for CC1-4L [clone 34] versus 12.4% ± 0.85% serum for vector-only; P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

CEACAM1-4L downregulates cell growth in response to EGF. (A) Cos-7 and MCF-7 cells were stably transfected with vector alone (+ Vec) or with cDNA encoding rat CEACAM1-4L (+ CC1-4L), EGFR (+ EGFR), or both (+ EGFR/CC1-4L). Cells were also transfected with cDNA encoding EGFR and CEACAM1_4S (+ EGFR/CC1-4S). Numbers in parentheses (in key) denote the clone number. After being incubated for 24 hours in serum-containing complete medium (maximal growth) or in serum-free medium supplemented with 0.1% BSA either alone (basal growth) or with 100 nM EGF, cells were counted by the MTT method. EGF-induced cell growth was calculated as the percent maximal minus basal growth divided by the number of cells grown in complete medium. These experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated at least three times per clone. Data represent the mean ± SD of repeated experiments. At least two stable clones were examined. *P < 0.05 versus Vec; P < 0.05 versus EGFR (clone 28). (B) For examination of EGFR phosphorylation, serum-starved cells were treated with EGF as described in Figure 1 and lysed and the EGFR immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting with α-pTyr for detection of tyrosine-phosphorylated EGFR, and re-immunoblotting with α-EGFR to account for the amount of EGFR in the immunoprecipitates. (C) For examination of CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation, cell lysates were lectin-purified prior to phosphorylation in the presence of EGF and [γ-32P]ATP, immunoprecipitation of CEACAM1-4L, and analysis of its phosphorylation by autoradiography (upper gel). To account for the amount of CEACAM1-4L in the immunoprecipitate, proteins were reprobed with α-CC1 (lower gel).

Expression of EGFR in MCF-7 cells increased cell growth in response to EGF (Figure 5A, 7.43% ± 0.35% serum for EGFR [clone 28] versus 4.92% ± 0.75% serum for vector-only; P < 0.05). Coexpression of CEACAM1-4L, which undergoes phosphorylation by EGFR in response to EGF (Figure 5C, lane 10 versus lane 9), substantially decreased growth in response to EGF compared with that of cells expressing vector or EGFR alone (2.95% ± 0.22% serum for EGFR/CC1-4L [clone 10] versus 4.92% ± 0.75% serum for vector-only and 7.43% ± 0.35% serum for EGFR-only [clone 28]; P < 0.05). In contrast, coexpression of CEACAM1-4S, which does not undergo phosphorylation by EGFR (Figure 5C, lane 12 versus lane 11), did not decrease growth in response to EGF compared with that of cells expressing EGFR or vector alone (6.88% ± 0.29% serum for EGFR/CC1-4S [clone 16] versus 7.43% ± 0.35% serum for EGFR-only [clone 28] and 4.92% ± 0.75% serum for vector-only). The results were similar in at least two stable transfectants in each transfection. Taken together, the data suggest that upon its phosphorylation by EGFR, CEACAM1-4L reduces EGF-dependent cell growth.

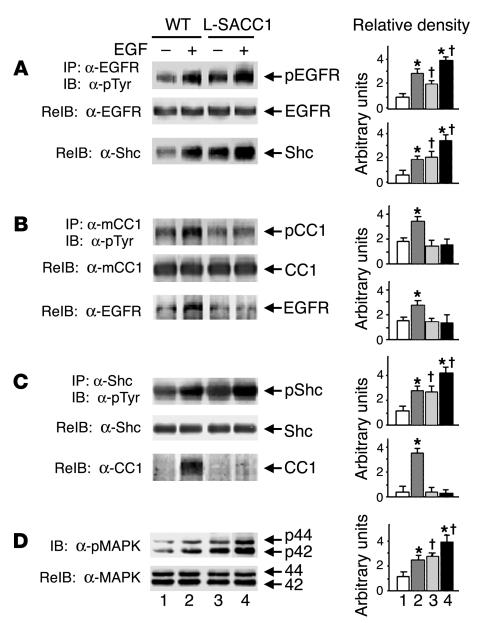

To further investigate whether CEACAM1-4L is a substrate of EGFR and whether intact phosphorylation on Ser503 is required for CEACAM1-4L to undergo EGF-induced phosphorylation, we examined EGFR signaling in hepatocytes of L-SACC1 mice. To this end, we subjected equal amounts of proteins from liver lysates to phosphorylation by EGF in the presence of ATP prior to immunoprecipitation with α-EGFR (Figure 6A), α–mouse CEACAM1-4L (α-mCC1; Figure 6B), and α-Shc (Figure 6C) and immunoblotting with α-pTyr. After correcting for the amount of protein in the immunoprecipitate, as assessed by reprobing with the corresponding antibody (Figure 6, A–C, middle gels), EGF increased EGFR phosphorylation in WT as well as in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 6A, lane 2 versus lane 1 and lane 4 versus lane 3, respectively). The activated EGFR, however, failed to phosphorylate CEACAM1-4L in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 6B, lane 4 versus lane 3) as it did in WT mice (Figure 6B, lane 2 versus lane 1). The failure to phosphorylate CEACAM1-4L was specifically related to the S503A CEACAM1-4L mutation, as EGF-mediated Shc phosphorylation (Figure 6C), co-immunoprecipitation with EGFR (Figure 6A), and MAPK activity (Figure 6D), as assayed by immunodetection of phosphorylated MAPK (pMAPK) with α–phospho-p44/p42 MAPK (α-pMAPK) were intact in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 6, lane 4 versus lane 3 compared with lane 2 versus lane 1 in WT mice). Taken together, the data support the observation that CEACAM1-4L is a substrate of EGFR and that intact phosphorylation on Ser503 is required for CEACAM1-4L to undergo EGFR-mediated phosphorylation in response to EGF.

Figure 6.

Increased activation of EGFR-mediated mitogenesis pathways in L-SACC1 hepatocytes. (A_C) Livers were removed from 3 age-matched male mice and lysed and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to phosphorylation for 5 minutes in the presence of 50 μM ATP and EGF. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-EGFR (A), α-mCC1 (B), or α-Shc (C) prior to immunoblotting with α-pTyr for examination of tyrosine phosphorylation (upper gel of each panel). pShc, phosphorylated Shc. To account for these proteins in the immunoprecipitates, each of these gels was reprobed with the antibody that was used in immunoprecipitation (middle gel). For examination of the association between EGFR and Shc, CEACAM1-4L and EGFR, and Shc and CEACAM1-4L, α-EGFR immunoprecipitates were reprobed with α-Shc (A, lower gel); the α-CEACAM1-4L immunoprecipitates, with α-EGFR (B, lower gel); and the α-Shc immunoprecipitates, with α-CEACAM1-4L (C, lower gel). (D) For assay of MAPK activity, proteins were immunoblotted with α-pMAPK for assessment of phosphorylation of MAPK (p44 and p42; upper gel) and were reprobed with α-MAPK to account for the amount of this protein in the lysates (lower gel). Bars in graphs at right correspond to lanes in gels at left. *P < 0.05 versus (_) of both WT and L-SACC1; P < 0.05 versus (_) WT.

We have shown that upon its phosphorylation by the insulin receptor, CEACAM1-4L is indirectly associated with the receptor via Shc (21). Consistent with this model, reprobing of proteins in the Shc immunoprecipitate with α-CC1 (Figure 6C) revealed that EGF treatment significantly increased the association of CEACAM1-4L with Shc in WT mice (Figure 6C, lane 2 versus lane 1) but not in L-SACC1 mice (lane 4 versus lane 3). Furthermore, this was correlated with a markedly reduced association of CEACAM1-4L with EGFR in L-SACC1 mice, as shown by the lower amount of EGFR in CEACAM1-4L immunoprecipitates (Figure 6B, lane 4 versus lane 3 compared with lane 2 versus lane 1 in WT mice). Together with higher levels of binding of Shc to EGFR (Figure 6A) and phosphorylation (Figure 6C), and of MAPK activity (Figure 6D) in L-SACC1 mice in the presence of EGF (Figure 6, lane 4 versus lane 2), this suggests that when phosphorylated, CEACAM1-4L binds to EGFR indirectly via Shc and that this decreases coupling of Shc to the ras/MAPK pathway, thus downregulating cell growth in response to EGF.

Mechanism of elevated constitutive EGFR activation and cell proliferation in the L-SACC1 mouse liver.

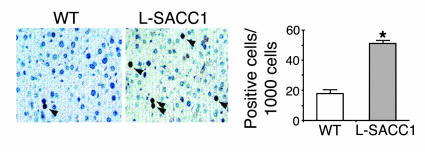

As Figure 6A reveals, basal EGFR phosphorylation in the absence of ligand was approximately 2- to 3-fold higher in L-SACC1 mouse livers than WT mouse livers after normalization for the amount of EGFR in the immunoprecipitates (Figure 6A, lane 3 versus lane 1). This was associated with a similar elevation in the interaction between EGFR and Shc (Figure 6A, lane 3 versus lane 1) and in basal Shc phosphorylation in L-SACC1 compared with that of WT mice (Figure 6C, lane 3 versus lane 1). Consistent with this finding, the activity of MAPK was approximately 3-fold higher in liver lysates of L-SACC1 mice than WT mice (Figure 6D, lane 3 versus lane 1). Furthermore, this was correlated with increased proliferation of hepatocytes in L-SACC1 mice, as shown by the approximately 2- to 3-fold increase in proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) labeling in immunohistochemical analyses of liver sections of 2-month-old L-SACC1 mice compared with WT mice (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Increased constitutive proliferation of L-SACC1 hepatocytes. Livers were removed from 2-month-old male L-SACC1 and WT mice for immunohistochemical analysis by PCNA labeling. Arrowheads indicate PCNA-positive cells. These experiments were repeated on at least 2 mice per genotype. Original magnification, ×40. Right, 5 sections per mouse were examined and 100 cells per site, for a total of 10 sites per section, were randomly counted, amounting to a total count of 5,000 cells per mouse. *P < 0.05 versus WT.

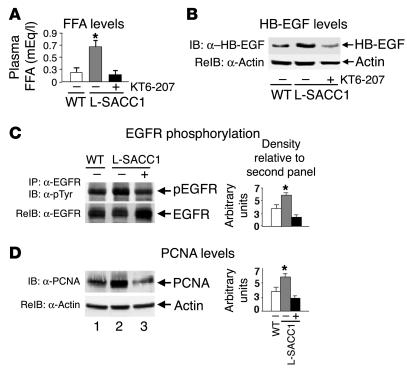

Because insulin receptor phosphorylation in L-SACC1 mouse liver is reduced by approximately 50% (9), insulin signaling does not significantly contribute to increased cell growth in L-SACC1 mice. Additionally, the amount of EGFR was not altered in L-SACC1 liver (not shown). Thus, constitutive hyperactivation of EGFR in L-SACC1 relative to WT mice could not be due to changes in EGFR levels. As expected from our previous studies (9), fasting plasma FFAs levels were elevated in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 8A, 0.71 ± 0.11 mEq/l in L-SACC1 versus 0.28 ± 0.10 mEq/l in WT; P < 0.05). Additionally, HB-EGF levels were elevated (by approximately 3-fold) in the adipose tissues of L-SACC1 compared with WT mice (Figure 8B, second lane versus first lane). Because FFAs and HB-EGF activate EGFR, we next examined whether elevation of the level of these adipokines underlies the increased activation of EGFR in L-SACC1 mice. To this end, we treated the mice with KT6-207, a PPARα/γ dual agonist, to reduce visceral obesity and the circulating levels of these adipokines. Treatment of L-SACC1 mice with this hypolipidemic agent for 3 weeks completely restored visceral obesity (not shown), plasma FFAs (Figure 8A, 0.14 ± 0.07 mEq/l in treated L-SACC1 versus 0.28 ± 0.10 mEq/l in WT), and HB-EGF levels (Figure 8B) in L-SACC1 mice. This was associated with reversal of EGFR phosphorylation in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 8C, lane 3 versus lane 1). Moreover, Western blot analysis of liver lysates with α-PCNA indicated that KT6-207 restored PCNA levels in L-SACC1 mice (Figure 8D, lane 3 versus lane 1). Thus, restoration of FFAs and HB-EGF levels in L-SACC1 mice normalizes EGFR activation and proliferation of hepatocytes. Taken together, the data suggest that elevation in visceral obesity and the levels of circulating adipokines, such as FFAs and HB-EGF, activates hepatic EGFR independently of EGF and increases hepatocyte proliferation in L-SACC1 mice.

Figure 8.

Elevated adipokines activate EGFR activation in L-SACC1 hepatocytes. Five age-matched male mice were treated with KT6-207 (+; black bars) or vehicle alone (_; gray bars for L-SACC1 mice and white bars for WT mice). (A) At the end of the treatment, blood was removed for determination of plasma FFA levels. (B) Visceral adipose tissues were removed from the intra-abdominal cavity and lysed for sequential immunoblotting with α_HB-EGF followed by α-actin for determination of HB-EGF content. (C) Livers were removed from age-matched mice and lysed and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with α-EGFR prior to sequential immunoblotting with α-pTyr for examination of EGFR phosphorylation and α-EGFR to account for the amount of this protein in the immunoprecipitates. (D) Equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with α-PCNA and were normalized by reprobing with α-actin for determination of cell proliferation. *P < 0.05 versus (_) WT.

Discussion

In this report, we have shown that CEACAM1-4L is a shared substrate of insulin and EGFRs and that it is phosphorylated by both receptors at the same site. Phosphorylation of CEACAM1-4L by EGFR occurs on Tyr488, not Tyr513, and it requires prior phosphorylation of Ser503. These observations in cellular systems are buttressed by data in L-SACC1–transgenic animals expressing the phosphorylation-defective S503A CEACAM1-4L mutant in liver. Using two different cell types, MCF-7 and Cos-7 cells, we have also shown that transfection of CEACAM1-4L decreases cell growth in response to EGF. As with insulin (20, 25), this function of CEACAM1-4L requires its phosphorylation by EGFR, as the long but not the short isoform of CEACAM1 downregulates EGFR-mediated cell growth. In contrast to EGFR and insulin, CEACAM1-4L does not affect cell growth via IGF-1 receptors (IGF-1Rs), which fail to phosphorylate it (20, 25). Because EGFR signaling plays a major role in advanced cancers in tissues of epithelial origin (24), regulation of its mitogenic action by CEACAM1-4L may constitute a potential mechanism of the tumor suppression function of CEACAM1-4L.

The insulin receptor mainly regulates metabolism (48). Among insulin target tissues, CEACAM1-4L is expressed only in the liver, the major site of insulin clearance, but not in muscle and adipose tissue, where insulin clearance is negligible. Its inactivation in liver impairs insulin clearance, leading to hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in L-SACC1 mice. It also causes visceral obesity with high circulating levels of FFAs that are commonly released from the adipose tissue into the portal circulation in insulin resistance and obesity (43, 44). The production of HB-EGF in the adipose tissue of L-SACC1 mice is also increased. Consistent with the notion that these adipokines, FFAs and HB-EGF, activate EGFR independently of EGF, EGFR is constitutively activated in L-SACC1 hepatocytes but is inactive in WT hepatocytes. This occurs in the absence of an increase in EGFR levels in L-SACC1 hepatocytes. With its defective phosphorylation in L-SACC1 hepatocytes, the ability of CEACAM1-4L to bind Shc and sequester it is blunted. This in turn increases the amount of Shc available to bind to EGFR and undergo phosphorylation by the receptor, leading to increased coupling of EGFR to the ras/MAPK mitogenesis pathway. Activation of this pathway leads to increased cell proliferation compared with that of WT mice. Because the level of IGF-1R in the hepatocyte is negligible and insulin signaling is downregulated in these insulin-resistant mice, increased cell proliferation and PCNA labeling must be mediated mainly by EGFR activation. The reversal of EGFR activation and cell proliferation in L-SACC1 hepatocytes by a reduction in visceral obesity and plasma adipokines with KT6-207 supports this hypothesis. The promotion of proliferation of hepatocytes in L-SACC1 mice by HB-EGF is in agreement with its reported mitogenic action in liver regeneration (49) and with its role in normal development, as has been highlighted by the observation that deletion of the gene encoding HB-EGF in mice is lethal (50). Thus, the L-SACC1 mouse also demonstrates that hepatic CEACAM1-4L inactivation raises the level of insulin, which in turn causes visceral obesity with increased FFAs and HB-EGF output. This in turn activates EGFR in the hepatocyte, independently of EGF, and increases cell proliferation. Our observation is consistent with the notion that by activating the EGFR-dependent mitogenesis pathway, FFAs link altered metabolism with aberrant cell growth (38, 42). The association between altered visceral obesity and uncontrolled cell growth is emphasized by the effectiveness of the antidiabetic PPARγ agonists in reducing and preventing tumorigenesis in rodents and cell growth in cell systems (51).

Because liver inactivation of CEACAM1-4L causes metabolic derangement and increases hepatocyte proliferation in L-SACC1 mice, our data here provide evidence that CEACAM1-4L plays a central role in associating central obesity and insulin resistance with activation of EGFR and aberrant epithelial cell growth. Further studies are needed to examine whether this constitutes a molecular basis of increased neoplastic transformation in states of altered lipid metabolism.

Methods

Phenotypic and biochemical characterization of animals.

Generation of L-SACC1 mice was described previously (9). Animals were kept on a 12-hour dark/light cycle and were fed standard chow ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee. Six-month-old male mice were subjected to a daily dose of 3 mg/kg body weight of the PPARα/γ dual agonist KT6-207 (Kotobuki Pharmaceutical Co.), or of vehicle alone, by oral gavage for 3 weeks. At the end of treatment period, mice were fasted overnight (from 17:00 one day to 11:00 the next day) and venous blood was removed from the retro-orbital sinuses for measurement of plasma FFA levels with the NEFA C kit (Wako Diagnostics). Intra-abdominal fat was removed and weighed, and this weight was divided by body weight for measurement of visceral obesity (9). The adipose tissue was lysed and its proteins were analyzed by standard Western blot with goat polyclonal antibody against the carboxy-terminal domain of human HB-EGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) for assessment of the level of HB-EGF.

Cell culture.

MDA-MB468 human breast cancer cells were maintained in Leibovitz’s L-15 media (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a CO2-free incubator. Cos-7 monkey kidney epithelial cells, MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, and HT29p human colon cancer cells (52) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) or RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies) in a 5% CO2 incubator. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; from Cellgro or from Life Technologies), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% glutamine (Invitrogen).

Stable transfection.

Synthesis and subcloning into the bovine papilloma virus–based expression vector (pBPV; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) of the cDNA encoding CEACAM1-4L and -4S were described previously (7). Stable transfection of Cos-7 cells with 15 μg of pBPV-Ceacam1 cDNA in the presence of 1.5 μg of RSV-Neor was achieved by the lipofectAMINE method (Invitrogen), as described previously (7). Similar techniques were used for cotransfection of MCF-7 cells with pEGFP-N1-Egfr cDNA (53). Individual clones were expanded and maintained in medium containing Geneticin (G418; 600 μg/ml). Confluent cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (7) prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with α-CC1, as described previously (21). Screening for expression of EGFRs was achieved by measurement of EGF binding in intact cells, as described previously (7, 26).

Adenovirus infection.

MDA-MB468 cells were grown to a density of approximately 106 cells per plate, after which they were infected with Ad Cc1 or Ad Cont (1 × 109 PFU for 48 hours), as described previously (54).

Phosphorylation and signaling.

For phosphorylation of proteins in liver lysates, livers were removed from anesthetized animals, frozen immediately, and homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 in the presence of phosphatase and protease inhibitors) (7). Lysates were treated with 100 nM EGF (Upstate Biotechnology Inc.) or buffer alone for 5 minutes prior to phosphorylation in the presence of 50 μM ATP. Proteins were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal α-mCC1 (9), EGFR (M18; Upstate Biotechnology Inc.) and α-Shc (N-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). In some experiments, proteins were also immunoprecipitated with monoclonal α-pTyr from Cell Signaling Technology. After immunoprecipitation, proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes prior to immunoblotting with monoclonal α-pTyr (Upstate Biotechnology Inc.) followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated α-IgG, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and quantification by densitometry. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously (21). MAPK activity was assayed by measuring the amount of phosphorylated MAPK, assessed by immunoblotting with α-p44/42 MAPK (Thr 202/Thr 204; Cell Signaling), relative to the amount of MAPK as measured by re-immunoblotting with α-p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling).

For CEACAM1-4L phosphorylation in transfected cells, glycosylated proteins in cell lysates were partially purified by lectin affinity chromatography (EY Laboratories) (20) prior to undergoing phosphorylation, as described above, with the exception that this was performed in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The phosphorylated product was immunoprecipitated with monoclonal HA4 c19 α-rat CEACAM1-4L and was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (7) and autoradiography. For normalization for the amount of CEACAM1-4L in the immunoprecipitate, proteins were immunoblotted with the polyclonal α-CC1 antibody, against rat CEACAM1-4L (21).

For phosphorylation in intact cells, cells were starved of serum for 12 hours in the presence of 0.1% insulin-free BSA (Invitrogen) and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and were treated with 100 nM EGF (Upstate Biotechnology Inc.) or buffer alone for 0–10 minutes prior to lysis. HT29p cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 20 mM sodium orthovanadate, protease inhibitors, and 48 mM octyl-D-glucopyranoside; other cells, in 1% Triton X-100 in the presence of phosphatase and protease inhibitors (7). After immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies, as indicated in the Results section, proteins were analyzed by 7% SDS-PAGE, Western blot analysis, and detection by ECL. For immunodetection of CEACAM1-4L in HT29p cells, α-C1N3, the antibody against human pancreatic CEACAM (56) that detects CEA and CEACAM1 with a specificity comparable to T84.1 (57), was used. In some experiments, serum-starved HT29p cells were preincubated with 2 μM of the EGFR kinase–specific inhibitor PD168393 (Calbiochem) for 1 hour (55) prior to EGF stimulation.

GST pull-down assay.

Unless indicated otherwise, GST–CEACAM1-4L fusion peptides were as described previously (7). The cDNA fragment (nucleotides [nt] 1,345–1,560) encoding the cytoplasmic tail of rat CEACAM1-4L with mutation of Ser503 to Asp (S503D) was amplified in a PCR reaction with WT cDNA as template and 5′-gaattcATGGGATCCAGGAAGACTGGCGGGGGA-3′ and 5′-gcggccgcTCACTTCTTTTTGACTACCGAATAAACTGTTTCTGTGGGGCTTGAAGAGGCATCAGT-3′ as forward and reverse primers. The forward primer (nt 1,345–1,365) contained an EcoRI restriction site and the reverse primer (nt 1,607–1,560), a NotI restriction site (lower-case letters) to allow for in-frame subcloning of the PCR product into the pGEX-4T-1 vector (Amersham Pharmacia). The forward primer contained codons for ATG translation initiation and glycine (underlined) (7). The reverse primer contained the GAT sequence (in bold) instead of TCA to encode the Ser503 to Asp mutation. A similar strategy was used for amplification of the S503E construct, with the reverse primer containing TTC instead of TCA to encode the Ser503 to Glu mutation. GST fusion peptides (10 μg) were phosphorylated by preactivated EGFR protein tyrosine kinase (0.25 U; Calbiochem) (with 50 μM ATP, 75 mM MgCl2, 50 mM MnCl2, and 0.5 mg/ml BSA) in the presence of 70 μCi [γ-32P]ATP and were allowed to bind (60 minutes at 4°C) prior to being washed in HNTG buffer (150 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol) containing 1% Triton X-100 and analyzed by electrophoresis (27). Standard Western blotting techniques with α-EGFR were used for assessment of protein binding. The amount of GST peptides and their incorporated 32P were assessed by Ponceau S staining and autoradiography, respectively.

Cell growth.

Cells were seeded in triplicate into 12-well plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well and were allowed to attach in complete medium and then were incubated in serum-free/phenol red–free/FFA-free medium for 24 hours to reach quiescence. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium (basal growth), complete medium (maximal growth), or serum-free medium supplemented with 100 nM EGF for 48 hours prior to being counted by the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide) method (Sigma-Aldrich) (58). EGF-induced cell growth was calculated as the percent maximal minus basal growth divided by the number of cells grown in complete medium (20). These experiments were repeated at least three times for each clone.

PCNA labeling.

Cell proliferation in liver was assayed by standard Western blot analysis using monoclonal α-PCNA (PC-10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) and by immunohistochemical analysis (59). Briefly, mouse livers were sectioned (5 μm) and fixed in formalin, and the endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 0.3% H2O2/methanol. After being blocked with normal serum in PBS for 1 hour, liver sections were incubated for 1 hour with monoclonal α-PCNA (PC-10; Sigma-Aldrich) (1:100 dilution in 1% normal serum/PBS), washed in PBS, and incubated for 30 minutes with biotinylated α-mouse IgG. Sections were then incubated for 30 minutes with ABC complex (Vector Laboratories), colored with DAB peroxidase substrate, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Quantification of PCNA-stained nuclei was based on scoring 1,000 hepatocytes in each lobe for a total of 5,000 hepatocytes per mouse. These experiments were performed on two mice per genotype.

Quantification of proteins and statistical analysis.

Autoradiograms were scanned on an imaging densitometer (Bio-Rad) and proteins were quantified using SPECTRA MAX Plus (Molecular Devices) with the SoftMAX Pro Macintosh software program. Data were analyzed with Statview software (Abacus concepts) using one factor ANOVA analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alexander Sorkin (University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA) for providing the cDNA encoding human EGFR, and Paula Kramer (Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, Ohio, USA) for technical assistance with immunohistochemistry. This work was supported by NIH grants DK-54254 and DK-57497 (to S.M. Najjar), CA-86342 and CA-64856 (to S.-H. Lin), by an American Diabetes Association Research Award (to S.M. Najjar), by an Interdisziplinäres Zentrum Für Krebsforschung (IZKF) Faculty Grant (to H. Kalthoff), and by Strathmann Biotech AG, Germany (to D. May).

Footnotes

G.A. Abou-Rjaily and S.J. Lee contributed equally to this work.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: Ad Cc1, adenovirus vector containing cDNA encoding CEACAM1-4L; Ad Cont, adenovirus control; α-CC1, polyclonal α–rat CEACAM1-4L; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CEACAM1, CEA-related cell adhesion molecule; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; IGF-1R, IGF-1 receptor; L-SACC1, liver-specific overexpression of the phosphorylation-defective S503A CEACAM1-4L mutant; α-mCC1, α–mouse CEACAM1-4L; nt, nucleotides; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; α-pMAPK, α–phospho-p44/p42 MAPK; α-pTyr, α-phosphotyrosine.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Blenis J. Signal transduction via the MAP kinases: proceed at your own RSK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5889–5892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crews CM, Erikson RL. Extracellular signals and reversible protein phosphorylation: what to Mek of it all. Cell. 1993;74:215–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90411-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway [review] Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadekova S, Lamarche-Vane N, Li X, Beauchemin N. The CEACAM1-L glyco-protein associates with the actin cytoskeleton and localizes to cell-cell contact through activation of Rho-like GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:65–77. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagener C, Ergun S. Angiogenic properties of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;261:19–24. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najjar SM, et al. pp120/ecto-ATPase, an endogenous substrate of the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase, is expressed as two variably spliced isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1201–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najjar SM, et al. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of recombinant pp120/HA4, an endogenous substrate of the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9341–9349. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber M, et al. The carboxy-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poy MN, et al. CEACAM1 regulates insulin clearance in liver. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:270–276. doi: 10.1038/ng840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumaier M, et al. Biliary glycoprotein, a potential human cell adhesion molecule, is down-regulated in colorectal carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:10744–10748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson NL, Lin SH, Panzica MA, Hixson DC. Cell CAM 105 isoform RNA expression is differentially regulated during rat liver regeneration and carcinogenesis. Pathobiology. 1994;62:209–220. doi: 10.1159/000163912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummer J, Neumaier M, Gopfert C, Wagener C. Association of pp60c-src with biliary glycoprotein (CD66a), an adhesion molecule of the carcinoembryonic antigen family downregulated in colorectal carcinomas. Oncogene. 1995;11:1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turbide C, Kunath T, Daniels E, Beauchemin N. Optimal ratios of biliary glycoprotein isoforms required for inhibition of colonic tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2781–2788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, et al. Expression of biliary glycoprotein (CD66a) in normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Anticancer. 1998;18:3203–3212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phan D, et al. Identification of Sp2 as a transcriptional repressor of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3072–3078. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunath T, Ordonez-Garcia C, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. Inhibition of colonic tumor cell growth by biliary glycoprotein. Oncogene. 1995;11:2375–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh J-T, et al. Tumor suppressive role of an androgen-regulated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM) in prostate carcinoma cell revealed by sense and antisense approaches. Cancer Res. 1995;55:190–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinerman DI, et al. Suppression of human bladder cancer growth by increased expression of C-CAM1 gene in an orthotopic model. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3431–3425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo W, Wood CG, Earley K, Hung MC, Lin SH. Suppression of tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells by an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM1): the adhesion and growth suppression are mediated by different domains. Oncogene. 1997;14:1697–1704. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soni P, Lakkis M, Poy MN, Fernstrom MA, Najjar SM. The differential effects of pp120 (Ceacam 1) on the mitogenic action of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 are regulated by the nonconserved tyrosine 1316 in the insulin receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:3896–3905. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3896-3905.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poy MN, Ruch RJ, Fernström MA, Okabayashi Y, Najjar SM. Shc and CEACAM1 interact to regulate the mitogenic action of insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:1076–1084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer BB, Scheffrahn I, Obrink B. The tumor growth-inhibiting cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1 (C-CAM) is differently expressed in proliferating and quiescent epithelial cells and regulates cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1236–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estrera VT, Chen DT, Luo W, Hixson DC, Lin S-H. Signal transduction by the CEACAM1 tumor suppressor. Phosphorylation of serine 503 is required for growth-inhibitory activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15547–15553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lui VW, Grandis JR. EGFR-mediated cell cycle regulation. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Formisano P, et al. Receptor-mediated internalization of insulin. Potential role of pp120/HA4, a substrate of the insulin receptor kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:24073–24077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Calzi S, Choice CV, Najjar SM. Differential effect of pp120 on insulin endocytosis by two variant insulin receptor isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:E801–E808. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.4.E801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choice CV, Howard MJ, Poy MN, Hankin MH, Najjar SM. Insulin stimulates pp120 endocytosis in cells co-expressing insulin receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22194–22200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najjar SM, Choice CV, Soni P, Whitman CM, Poy MN. Effect of pp120 on receptor-mediated insulin endocytosis is regulated by the juxtamembrane domain of the insulin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12923–12928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldeweg SE, et al. Insulin resistance, lipid and fatty acid concentrations in 867 healthy Europeans. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR) Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;30:45–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bays H, Mandarino L, DeFronzo RA. Role of the adipocyte, free fatty acids, and ectopic fat in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor agonists provide a rational therapeutic approach [review] J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:463–478. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis GF, Carpentier A, Adeli K, Giacca A. Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol. Rev. 2002;23:201–229. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groop LC, Bonadonna RC, Shank M, Petrides AS, DeFronzo RA. Role of free fatty acids and insulin in determining free fatty acid and lipid oxidation in man. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;87:83–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI115005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvie M, Hooper L, Howell AH. Central obesity and breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2003;4:157–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin S, Parker RS. The effects of dietary fat and selenium on the development of preneoplastic lesions in rat liver. Nutr. Cancer. 1986;8:273–282. doi: 10.1080/01635588609513904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connolly JM, Liu XH, Rose DP. Effects of dietary menhaden oil, soy, and a cyclooxygenase inhibitor on human breast cancer cell growth and metastasis in nude mice. Nutr. Cancer. 1997;29:48–54. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy RW, Wickramasinghe NS, Ke SC, Wells A. Fatty acids and breast cancer cell proliferation [review] Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997;422:57–69. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2670-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mollerup S, Haugen A. Differential effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on cell proliferation during human epithelial in vitro carcinogenesis: involvement of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase. Br. J. Cancer. 1996;74:613–618. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulin NO, Sorokin A, Douglas JG. Arachidonate-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor and Shc-Grb2-Sos association. Hypertension. 1998;32:1089–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vacaresse N, et al. Activation of epithelial growth factor receptor pathway by unsaturated fatty acids. Circ. Res. 1999;85:892–899. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells A. EGF receptor. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999;31:637–643. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cowing BE, Saker KE. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and epidermal growth factor receptor/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in mammary cancer [review] J. Nutr. 2001;131:1125–1128. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hajri T, Han XX, Bonen A, Abumrad NA. Defective fatty acid uptake modulates insulin responsiveness and metabolic responses to diet in CD36-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1381–1389. doi:10.1172/200214596. doi: 10.1172/JCI14596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hegarty BD, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW, Furler SM. Increased efficiency of fatty acid uptake contributes to lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle of high fat-fed insulin-resistant rats. Diabetes. 2002;51:1477–1484. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higashiyama S, Abraham JA, Miller J, Fiddes JC, Klagsbrun M. A heparin-binding growth factor secreted by macrophage-like cells that is related to EGF. Science. 1991;251:836–939. doi: 10.1126/science.1840698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips SA, Perrotti N, Taylor SI. Rat liver membranes contain a 120 kDa glycoprotein which serves as a substrate for the tyrosine kinases of the receptors for insulin and epidermal growth factor. FEBS Lett. 1987;212:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fahlgren A, et al. Interferon-gamma tempers the expression of carcinoembryonic antigen family molecules in human colon cells: a possible role in innate mucosal defence. Scand. J. Immunol. 2003;58:628–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2003.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Accili D, Kido Y, Nakae J, Lauro D, Park B-C. Genetics of type 2 diabetes: insights from targeted mouse mutants. Curr. Mol. Med. 2001;1:9–23. doi: 10.2174/1566524013364040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiso S, et al. Liver regeneration in heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor transgenic mice after partial hepatectomy. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:701–707. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson LF, et al. Defective valvulogenesis in HB-EGF and TACE-null mice is associated with aberrant BMP signaling. EMBO J. 2003;22:2704–2716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koeffler HP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang M, Vogel I, Kalthoff H. Correlation between metastatic potential and variants from colorectal tumor cell line HT-29. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2627–2631. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carter RE, Sorkin A. Endocytosis of functional epidermal growth factor receptor-green fluorescent protein chimera. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:35000–35007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kleinerman DI, et al. Application of a tumor suppressor (C-CAM1)-expressing recombinant adenovirus in androgen-independent human prostate cancer therapy: a preclinical study. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2831–2836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fry DW, et al. Specific, irreversible inactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and erbB2, by a new class of tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:12022–12027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmiegel WH, et al. Monoclonal antibody-defined human pancreatic cancer-associated antigens. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1402–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagener C, Clark BR, Rickard KJ, Shively JE. Monoclonal antibodies for carcinoembryonic antigen and related antigens as a model system: determination of affinities and specificities of monoclonal antibodies by using biotin-labeled antibodies and avidin as precipitating agent in a solution phase immunoassay. J. Immunol. 1983;130:2302–2307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee SJ, Sung JH, Lee SJ, Moon CK, Lee BH. Antitumor activity of a novel ginseng saponin metabolite in human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells resistant to cisplatin. Cancer Lett. 1999;144:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steinbrecher KA, Wowk SA, Rudolph JA, Witte DP, Cohen MB. Targeted inactivation of the mouse guanylin gene results in altered dynamics of colonic epithelial proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:2169–2178. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64494-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]