Abstract

Background and Aims:

Pain reduction is important for rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. Intra- and peri-articular infiltration with local anesthetics may be an alternative to commonly used locoregional techniques. Adding pregabalin orally and s-ketamine intravenously may further reduce postoperative pain.

Material and Methods:

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study compared two methods of perioperative analgesia. Control patients received a standardized multimodal postoperative analgesic regime of paracetamol, diclofenac, and piritramide-patient-controlled analgesia, including ropivacaine knee infiltration during surgery. The study group received pregabalin orally and s-ketamine intravenously as an additional medication to the standard multimodal regimen. The control group received placebo.

Results:

The study group showed lower piritramide consumption during the first 24 h (P: 0.043), but with more side effects such as diplopia and dizziness.

Conclusion:

Addition of pregabalin and s-ketamine resulted in lower piritramide consumption during the first 24 h postoperatively. However, more investigation on benefits versus side effects of this medication is required.

Key words: pregabalin, s-ketamine, total knee arthroplasty

Introduction

Adequate analgesia is essential after total knee arthroplasty (TKA)[1,2] to improve postoperative mobilization and reduce the length of hospital stay (LOS). It is difficult to achieve good analgesia only with opioids, even when combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[3] Epidural analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks are frequently being used. They provide superior analgesia than opioids,[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] but cause muscle weakness, and risk of falling,[14,15] postponing the physiotherapy exercises, and prolonging the hospital stay. Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) has lately gained popularity.[16,17,18] LIA was also introduced in our institutional TKA protocol, replacing continuous femoral nerve block (CFNB). To make this transition successful, we needed some additional analgesics drugs. Consulting our pain team specialists and accepting multimodal analgesic strategy as standard practice in TKA patients,[19] we have chosen the addition of pregabalin[20,21,22,23] and s-ketamine[24,25] to the standard regimen. After obtaining good results of our pilot study (LIA-PREGABA-KET),[18] we started this randomized, double-blind trial to evaluate the opioid-sparing effect and benefits of pregabalin and s-ketamine, when added to a multimodal, standardized postoperative analgesic regime of LIA, paracetamol, diclofenac, and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA)-piritramide compared to placebo.

Material and Methods

After finishing the observational study[18] and prior to starting recruitment of the patients for the present trial, the protocol of this study was registered with the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR:9102) and also approved by the European Drug Registration Association (EUDRA CT-number: 2011-002019-27) and the CMO-Regional Ethics Committee on July 21, 2011. Patients with osteoarthritis scheduled for primary TKA were asked to participate and were randomly allocated to either study or control group. The inclusion of the patients took place at the Orthopedic Department, between November 2011 and May 2013. Exclusion criteria were patient refusal, pre-existing neurological or psychiatric illnesses, chronic pain syndrome, alcohol or drug abuse, risk of perioperative delirium, communication difficulties, rheumatoid arthritis, revision knee surgery, or participation in another study and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class >III. All patients signed written informed consent. The Clinical Pharmacology Department randomized the patients and supplied the coded study medication. Not a single person from the Department of Anesthesiology or the Orthopedics knew what medication was administered to any individual patient. Only after the last patient had been treated, the list with the randomization key was issued to the investigators.

Study design and intervention

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of analgesia after TKA where the control group received standardized multimodal analgesic regime of paracetamol, diclofenac, and piritramide-PCA, including ropivacaine knee infiltration during surgery (LIA). Pregabalin orally and s-ketamine intravenously were added to the study group whereas the control group received placebo (placebo capsules orally and normal saline intravenously).

Premedication consisted of two 500 mg paracetamol tablets (total 1000 mg) for all patients and of two capsules of 75 mg pregabalin (total 150 mg) or identical placebo capsules. The dose of pregabalin or placebo was reduced to one capsule ASA III patients and in patients >65 years of age.

According to their preoperative wishes, patients received spinal or general anesthesia. Bupivacaine plain 0.5% was used for spinal anesthesia. For induction of general anesthesia, patients received sufentanil, propofol, and rocuronium, if intubated, with inhalation of sevoflurane/oxygen/air for maintenance.

After the induction of anesthesia, the patients received a slow, intravenous (IV) bolus of 2 ml of s-ketamine (5 mg/ml) or placebo. Continuous infusion followed at a rate of 2 ml/h for 24 h. The bolus and the continuous infusion were reduced to 1 ml and 1 ml/h respectively in ASA III patients and in patients >65 years of age.

All patients received LIA during surgery. After cementing the components, 100 ml of ropivacaine 0.2% with epinephrine (1 mcg/ml) was used for infiltration of the posterior and the anterior knee capsule. Another 50 ml of ropivacaine 0.2% without epinephrine was injected in the subcutaneous tissue.

The IV study medication (an identical solution of s-ketamine or placebo) was continued for 24 h. Oral study medication (identical pregabalin or placebo capsules) was continued twice daily from the operation day to the 3rd postoperative day.

In the recovery room, a standard piritramide-PCA device (set at 1 mg bolus, 6 min lockout period) was connected and explained to all patients. They were encouraged to use PCA-piritramide in case of residual knee pain up to 48 h postoperatively. Paracetamol (1000 mg) and diclofenac (50 mg) were prescribed orally, 4 and 3 times a day, respectively, for the first 3 postoperative days.

The vital signs and AVPU scores (A for “alert,” V for “reacting to vocal stimuli,” P for “reacting to pain,” and U for “unconscious”) were used during the study period as a simple physiological scoring system suitable for bedside use in the ward. The side effects of medication such as dizziness, diplopia, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), constipation, and urine retention were noted.

Physiotherapy protocol

Our institution implemented a new fast-track physiotherapy protocol after the elective TKA. On the day of surgery, the patients were allowed to actively flex and extend the knee in bed. Guided exercise took place on the 1st and 2nd postoperative days. The physiotherapist used a goniometer to measure the progress in maximal knee flexion angle during the exercise. The patients exercised actively, twice daily, and were encouraged to make a move from bed to chair and to walk on the walkway. By day 3, the patients were expected to reach more than 70° flexion with the full extension of the knee. They should also be able to walk freely with elbow crutches and start climbing stairs. Succeeding in these exercises meant they reached the functional discharge criteria.

Objective of the study

The primary goal was to determine if the additional analgesics (pregabalin and s-ketamine) could reduce pain and opioid consumption.

The secondary goals were to examine if there was some improvement in postoperative knee flexion, reduction in the LOS, and to evaluate the side effects of the additional drugs.

Primary study parameters

Pain at rest, pain on movement, and piritramide consumption were recorded by a trained PACU or ward nurse. The standard numeric rating scale (NRS) was used to measure pain. The patient could grade the intensity of knee-related pain on a scale of 0–10, where 0 means no pain and 10 is the worst imaginable pain. Pain scores at rest (NRS-R) were taken and recorded by a nurse in the ward starting from day 0 (the operation day) to day 2, 3 times a day. Dynamic pain scores (NRS-D), from day 1, until the day of discharge, were recorded during the exercises by a specially instructed physical therapist. The piritramide consumption during the first 24 h and total consumption (48 h) were noted.

Secondary study parameters

The knee flexion angle was measured daily, from the 1st postoperative day (D-1) until the day of discharge (D-D), by a physical therapist as flexion 1, flexion 2, flexion 3, etc.

LOS presented the number of days between surgery and discharge from the hospital.

Drug side effects were as follows:

Local anesthetic toxicity and wound infection.

State of sedation (standard postoperative AVPU scores registration in the ward).

Diplopia, dizziness and PONV.

Urine retention and constipation.

Serious adverse events (SAE) reported.

Statistics

Sample size calculation was based on morphine consumption results from our previous study.[11] Assuming a level of significance of 5% and a power of 0.80, a minimum of 26 patients per group were required to detect a 30% reduction of morphine consumption. Due to a switch in our hospital protocol from morphine to piritramide, we accepted this because there is almost equipotency for these two drugs. It was also verified that this group size would suffice to detect a 5° improvement in knee flexion during physical therapy. To compensate for dropouts, 30 patients were included in each group. SPSS for Windows Version (16.0) Chicago: SPSS Inc. software was used for statistical analysis. The data were tested for a normal distribution with the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For comparing means of the primary endpoint results, an unpaired Student's t-test was used. The Chi-square test was used to detect differences in the incidence of medication side effects (number of nauseated or vomiting patients, dizziness, etc.). Data are presented as means and standard deviation or as numbers and frequency. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

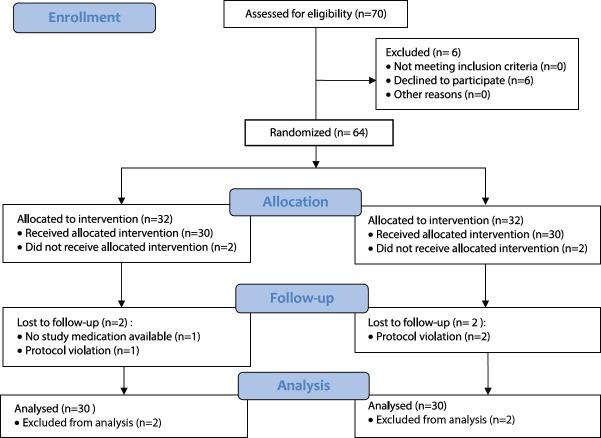

From November 2011 to May 2013, 70 patients scheduled for primary TKA were approached to participation in the study. There were patients who initially agreed to participate, but decided to withdraw on the day of surgery (n = 6). From the randomized patients, four patients were excluded later, due to violation of protocol in three cases and study medication not available in one case (n = 4). A total of 60 patients were included and followed (CONSORT-diagram, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

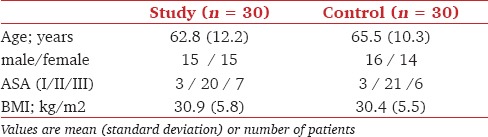

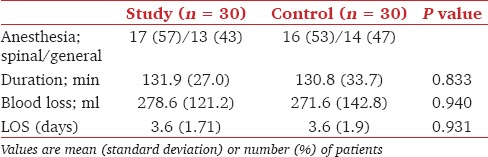

Patient characteristics were comparable in both groups: Age, gender, and the number of elderly. The majority of patients in both groups had ASA classification score II. Body mass index was also comparable [Table 1]. The same refers to the number of patients receiving spinal or general anesthesia, duration of surgery, and blood loss [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

Table 2.

Type of anaesthesia, total duration of the procedure (including anaesthesia and surgery time) intraoperative blood loss and length of hospital stay (LOS). Values are mean (SD) or number (proportion)

Primary study parameters

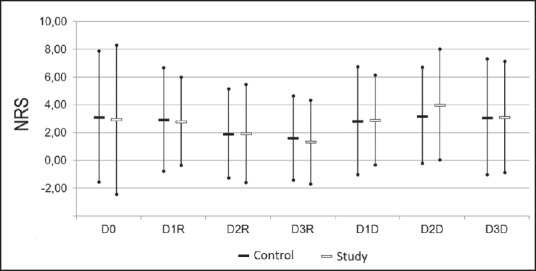

Pain scores at rest (NRS-R) and the dynamic pain scores (NRS-D) were comparable between the study and the control group during the first 48 h [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

NRS for days (D) 0–3 for ‘rest’ (R) and‘dynamic’ (D): mean with 95% confidence intervals. Results are presented for patients in the control group (black bars) and study group (white bars).

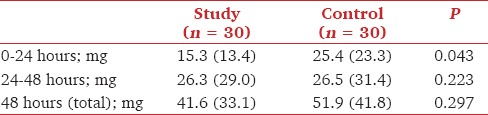

Piritramide consumption was lower in the study group on the day of surgery. On the 2nd postoperative day, the piritramide consumption was higher than the previous day, but similar in both groups. Total piritramide consumption was similar in the two groups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Use of piritramide in the study and control groups for the first 24 hours, the second 24 hours, and for 48 hours post surgery. Values are mean (SD)

Secondary study parameters — The side effects of medication

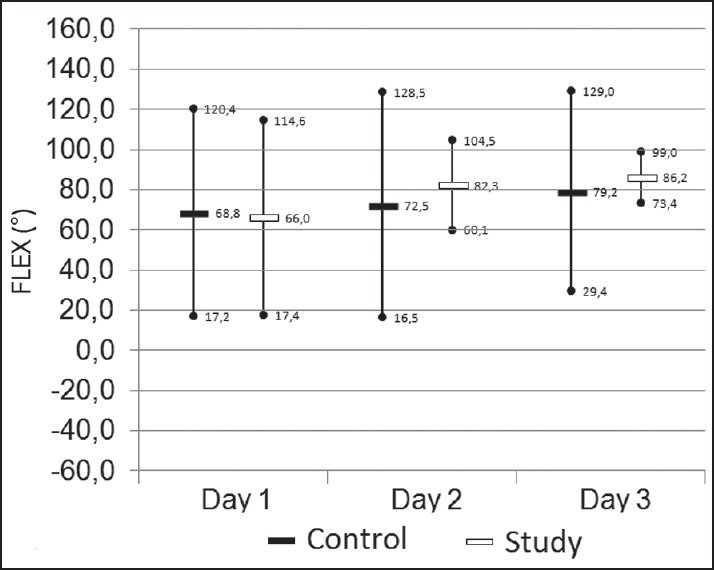

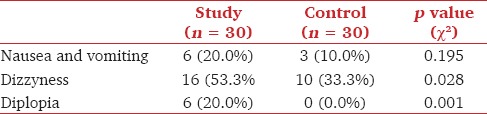

Knee flexion angle was measured from the 1st until the 3rd postoperative day. Although not statistically significant, the study group achieved better knee flexion results on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative day [Figure 3]. There was no difference in the LOS between the study and control group [Table 2]. No altered state of sedation was noted due to the study medication. The AVPU scores in the ward were maximal in both patient groups. Diplopia was only registered in the study group (n = 6). PONV was noted in both groups, whereas dizziness was more frequently present in the study group [Table 4]. Urine retention (n = 1), constipation (n = 3), and opioid side effects were only found in the control group. There were neither signs of local anesthetic toxicity nor wound infection reported. One SAE was reported in the study group. The patient had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) on the 3rd postoperative day at home. This patient had a past history of multiple previous TIA's.

Figure 3.

The knee flexion (degrees) on day one to three. Mean values with 95% confidence intervals. The results are for the patients in the control group (black bars), for the study group (white bars).

Table 4.

Number of patients with the occurrence of side effects

Discussion

This study showed a statistically significant lower opioid consumption in the study group versus control group during the first 24 h after TKA. However, after 24 h, after stopping s-ketamine and starting guided physiotherapy exercises, the piritramide consumption increased in both groups and was comparable.

Previous studies show that pain reduction is an important factor for early mobilization after (TKA).[1,2] As opioids alone are not sufficient for an adequate analgesia, a multimodal analgesic approach has been accepted recently.[3] Analgesic benefits of peripheral nerve blocks are well described.[4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Femoral nerve block, single shot or continuous (CFNB), also in combination with sciatic and/or obturator block is proven to provide superior analgesia to opioids alone.[11,12,13] The main problems with these peripheral nerve blocks are prolonged muscle weakness, the risk of falling during exercise, and decubitus on pressure points, as described after sciatic nerve block.[14,15] For this reason, intraoperative LIA administered by the surgeons has gained popularity.[16,17] Due to its simplicity and low complication risk, it might replace locoregional techniques.[18] There is some evidence that pregabalin[19,20,21,22,23] and s-ketamine[19,24,25] may reduce acute pain, decrease opioid consumption, and even an incidence of chronic pain.

With good clinical results in our observational study (LIA-PREGABA-KET)[18] which included 20 TKA patients, we started this prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled evaluation of analgesia after TKA with LIA, where the study group received additional pain medication, pregabalin, and s-ketamine, whereas the control group received placebo.

As a result, lower piritramide consumption in the first 24 h and a trend of better postoperative knee flexion on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days were present. However, the pain scores at rest and during the exercise were comparable between the groups. Most patients in both groups achieved functional discharge criteria on the 3rd postoperative day.

There were neither signs of local anesthetic toxicity nor infections reported due to LIA in any of the patients, but more medication-related side effects were registered in the study group. Diplopia, a known side effect of pregabalin, was noted within the first 24 h only in the study patients (n = 6). As we used s-ketamine at this time, which is known to cause nystagmus and sometimes diplopia, possibly it also contributed to this problem.

Dizziness appeared in one-half of study and one-third of control patients. In general, orthostatic dizziness[2] is a well-known postoperative problem in orthopedic patients. It presents itself frequently while the patient attempts to come out of bed on the 1st postoperative day. In our patients, this was a transitory problem, rarely followed by general weakness and causing minor delay in exercises. In a few patients, low hemoglobin count may have caused this problem. If we assume that an equal number of study and control patients had the orthostatic dizziness, the higher incidence of dizziness in the study group was probably a result of pregabalin side effects,[21] since the s-ketamine was already stopped.

This study showed no difference in LOS between the two groups. However, after introducing LIA, an important reduction in hospital stay has been achieved in our institution. In these LIA patient groups, a full physiotherapy regime including the walking test starts on the 1st postoperative day. This is possible since there is no nerve block-related quadriceps muscle weakness (CFNB) delaying the exercise, with falling accidents of 2.7% in spite of safety strategies.[14] Comparing this new LIA-PREGABA-KET study to our previous randomized controlled trial-TKA with CFNB,[11] not only an improved (mean) knee flexion angle is achieved on the day of discharge, but also LOS has now been shortened by 36 h, which brings an improved cost-benefit ratio. In general, the LOS following TKA in fast-track setups, with functional discharge criteria, has been reduced to about 3 days and our findings are in accordance with those of Husted et al.[1] While in earlier studies, patient's characteristics alone were used to predict LOS, these authors recommend that future efforts should focus on analgesia, the rapid recovery of muscle function, and prevention of orthostatic hypotension. In the present study, good analgesia and rapid recovery of muscle function appear to facilitate reduced LOS. However, no reduction in dizziness or orthostatic hypotension has been found. According to Husted et al., this is the third main cause of prolonged LOS. Nausea, vomiting, confusion, and sedation appear to delay discharge minimally.[1] Harsten et al.[2] have suggested that avoiding spinal anesthesia might result in less dizziness, muscle weakness, PONV, and even less postoperative pain. The present study could not confirm these findings. We also agree with Schug and Goddard[19] that recent advances in the pharmacological management of pain are not so much the result of new “miracle” drugs, but new ways of using old drugs often as components of a multimodal approach to pain relief.

The potential benefits of the study medications on the incidence of chronic postoperative pain still have to be investigated.

Limitations

Since the power analysis was used for opioid consumption, the number of patients and their high comorbidity may have limited the expression of differences in other parameters and might explain the wide variability in some results. Further investigation is also required to see whether a combination of both additional drugs is better than one of each.

Conclusion

A lower piritramide consumption was found in the pregabalin/s-ketamine group than in the placebo group during the first 24 h postoperatively. Furthermore, a trend of better knee flexion was present on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days. There were no side effects observed due to the LIA with ropivacaine/epinephrine mixture in any of the patients. However, the appearance of diplopia and more dizziness in the study group suggests that further studies are required to determine the lowest effective dose of pregabalin with optimal analgesic and functional results and minimal incidence of side effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to our colleague Dr. Eric Robertson for his contribution and also to Mrs. Ingrid Heijnen, Head orthopedic nurse, for all her help and effort.

References

- 1.Husted H, Lunn TH, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop. 2011;82:679–84. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harsten A, Kehlet H, Toksvig-Larsen S. Recovery after total intravenous general anaesthesia or spinal anaesthesia for total knee arthroplasty: A randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:391–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singelyn FJ, Deyaert M, Joris D, Pendeville E, Gouverneur JM. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous three-in-one block on postoperative pain and knee rehabilitation after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:88–92. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199807000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seet E, Leong WL, Yeo AS, Fook-Chong S. Effectiveness of 3-in-1 continuous femoral block of differing concentrations compared to patient controlled intravenous morphine for post total knee arthroplasty analgesia and knee rehabilitation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0603400110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salinas FV, Liu SS, Mulroy MF. The effect of single-injection femoral nerve block versus continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty on hospital length of stay and long-term functional recovery within an established clinical pathway. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1234–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000198675.20279.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chelly JE, Greger J, Gebhard R, Coupe K, Clyburn TA, Buckle R, et al. Continuous femoral blocks improve recovery and outcome of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:436–45. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chelly JE, Ben-David B. Do continuous femoral nerve blocks affect the hospital length of stay and functional outcome? Anesth Analg. 2007;104:996–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000258811.29571.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macalou D, Trueck S, Meuret P, Heck M, Vial F, Ouologuem S, et al. Postoperative analgesia after total knee replacement: The effect of an obturator nerve block added to the femoral 3-in-1 nerve block. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:251–4. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000121350.09915.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin AM, Kratz CD, Eberhart LH, Dinges G, Heider E, Schwarz N, et al. Postoperative analgesia and functional recovery after total-knee replacement: Comparison of a continuous posterior lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) block, a continuous femoral nerve block, and the combination of a continuous femoral and sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:434–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies AF, Seger EP, Murdoch J, Wright DE, Wilson IH. Epidural infusion or combined femoral and sciatic nerve block as perioperative analgesia for knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:393–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadic L, Boonstra MC, DE Waal Malefijt MC, Lako SJ, Van Egmond J, Driessen JJ. Continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:914–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul JE, Arya A, Hurlburt L, Cheng J, Thabane L, Tidy A, et al. Femoral nerve block improves analgesia outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1144–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f4b18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato K, Adachi T, Shirai N, Naoi N. Continuous versus single-injection sciatic nerve block added to continuous femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39:225–9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelt CE, Anderson AW, Anderson MB, Van Dine C, Peters CL. Postoperative falls after total knee arthroplasty in patients with a femoral nerve catheter: Can we reduce the incidence? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1154–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todkar M. Sciatic nerve block causing heel ulcer after total knee replacement in 36 patients. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:724–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spreng UJ, Dahl V, Hjall A, Fagerland MW, Ræder J. High-volume local infiltration analgesia combined with intravenous or local ketorolac morphine compared with epidural analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:675–82. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toftdahl K, Nikolajsen L, Haraldsted V, Madsen F, Tønnesen EK, Søballe K. Comparison of peri- and intraarticular analgesia with femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:172–9. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadic L, Niesten E, Heijnen I, Hofmans F, Wilder-Smith O, Driessen JJ, et al. The effect of addition of pregabalin and s-ketamine to local infiltration analgesia on the knee function outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2012;63:111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schug SA, Goddard C. Recent advances in the pharmacological management of acute and chronic pain. Ann Palliat Med. 2014;3:263–75. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2014.10.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Della Valle CJ, Kari M, Moric M, Tuman KJ. Perioperative oral pregabalin reduces chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:199–207. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c4273a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Ho KY, Wang Y. Efficacy of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain: A meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:454–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jain P, Jolly A, Bholla V, Adatia S, Sood J. Evaluation of efficacy of oral pregabalin in reducing postoperative pain in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop. 2012;46:646–52. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.104196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JK, Chung KS, Choi CH. The effect of a single dose of preemptive pregabalin administered with COX-2 inhibitor: A trial in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg ME, Torjman MC, Schwartzman RJ, Mager DE, Wainer IW. Pharmacodynamic profiles of ketamine (R)- and (S)- with 5-day inpatient infusion for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Physician. 2010;13:379–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adam F, Chauvin M, Du Manoir B, Langlois M, Sessler DI, Fletcher D. Small-dose ketamine infusion improves postoperative analgesia and rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:475–80. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000142117.82241.DC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]