Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to characterize tinnitus in affected patients.

Methods:

A retrospective review of medical records from 470 consecutive patients who visited a tertiary care hospital for evaluation of chronic subjective tinnitus between January 2009 and June 2010 was performed. Patients were divided into three subgroups based on age. Clinical, audiological, and psychological characteristics of each subgroup were analyzed.

Results:

Of the 470 patients evaluated, 85 were less than 40, 217 between 40 and 60, and 168 above 60 years of age. Most patients were men and complained of unilateral, acute high-pitched tinnitus. Most patients above the age of 40 years complained of loud and annoying tinnitus and had worse stress and severity scores.

Conclusions:

Chronic tinnitus in older adults is subjectively louder, more annoying, and more distressing than that found in younger patients. We recommend considering age in the patient management plan.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, distress, hearing loss, tinnitus

INTRODUCTION

Tinnitus has been reported in about 15% of the world population, most of them between the ages of 40 and 80 years.[1] The prevalence of chronic tinnitus increases with age, peaking at 14.3% in people 60–69 years of age.[2] The increase in prevalence of tinnitus with age is at least partly explained by the fact that hearing loss (HL) is an important risk factor for tinnitus;[3,4] 1–2% of people experiencing tinnitus develop anxiety, sleep disorders, or depression. It is not known why a few patients are truly disturbed and disabled by tinnitus. The amount of tinnitus distress appears to be associated with comorbid anxiety, comorbid depression, personality type, psychosocial situation, the amount of related HL, and the loudness of the tinnitus. The subjective nature of tinnitus, lack of objective quantification, diversity of causes, and heterogeneity of affected patients contribute to the poor understanding of stress related to tinnitus. We evaluated factors related to tinnitus to better understand patient morbidity and facilitate treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Two hundred and thirty-six women and 234 men with objective tinnitus visited the Tinnitus Clinic at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea, between January 2009 and June 2010. Patients were divided into three age groups for evaluation: under 40 years, 41–60 years, and over 60 years. All patients were evaluated using the same systematic protocol for evaluation of tinnitus and sound intolerance. This protocol was the basis for selecting the clinical data, features of tinnitus, and symptoms for review. Patients were evaluated using the Korean version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI). The THI score was graded as negligible (0–16), mild (18–36), moderate (38–56), severe (58–76), or catastrophic (78–100). The perceived stress was evaluated using the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version (BEPSI-K). The total score of the BEPSI-K was interpreted using three severity levels: low (<1.3), moderate (1.4–2.3), and severe (>2.4). The Beck's depression index (BDI) questionnaire was used for measuring depression and was scored as normal (1–10), mild (11–16), borderline (17–20), moderate (21–30), or severe (31–40). A complete clinical otorhinolaryngolic and head and neck examination was performed. Patients were evaluated using pure tone audiometry in an acoustically treated booth to test frequencies at 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 Hz (SA 203 audiometer; Entomed, Malmö, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

The influence of patient age on perceived tinnitus was evaluated. Tinnitus features and characteristics of all age groups were compared using the t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, depending on the data type. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

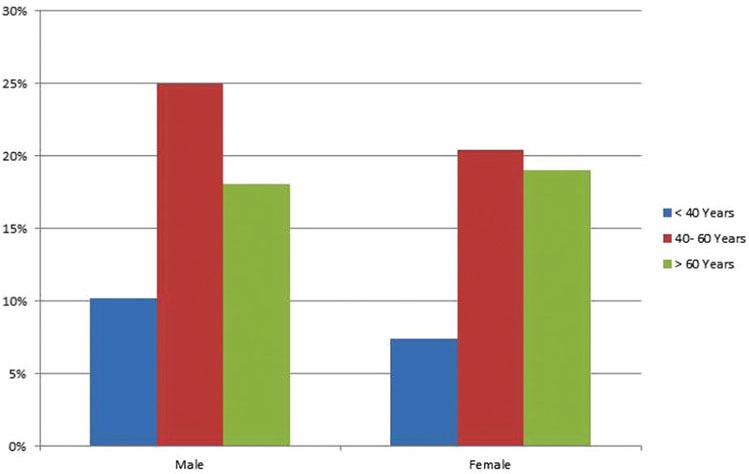

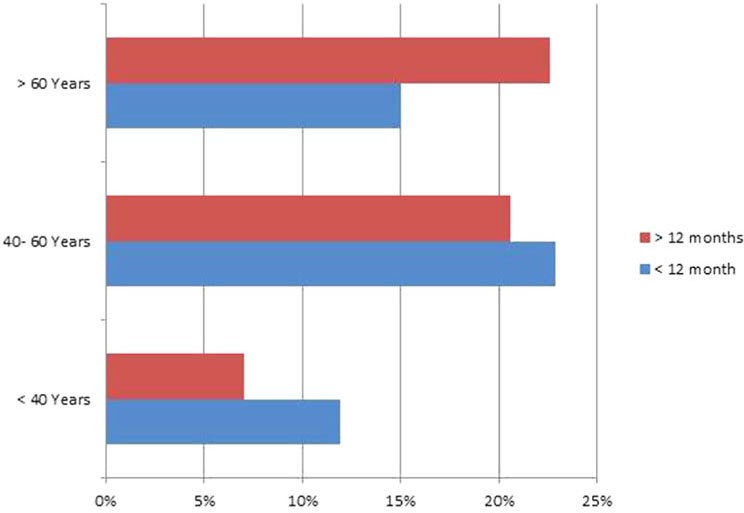

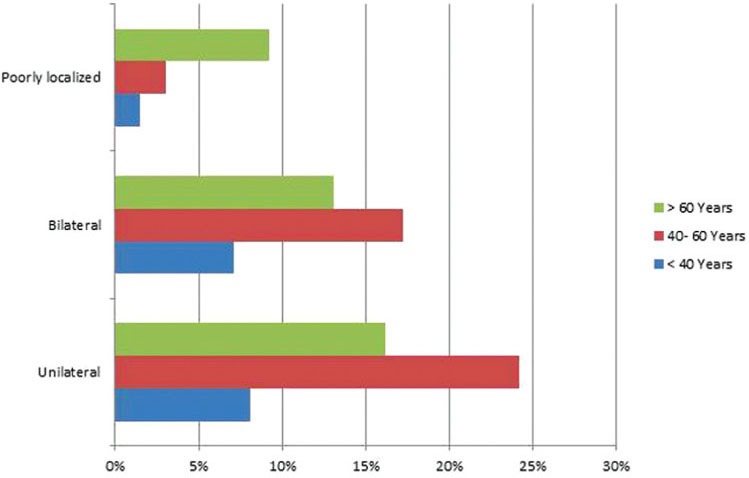

Four hundred and seventy patients, 234 men (49.8%) and 236 women (50.2%), were evaluated. The age of the patients ranged from 12 to 86 years [mean: 53 ± 7.9 (standard deviation) years]. The mean age among women was 54 years and among men was 51.5 years. There was no difference in patient age by sex; 18.1% of patients were less than 40 years of age, 46.2% were 40–60, and 35.7% were above 60. Patients of 40–60 years of age were seen most frequently (P=0.02, ANOVA); 45.9% of patients less than 40 year, 44.7% between 40 and 60, and 59.5% above 60 were women. Patients above 60 years of age were more frequently women (P=0.005, t test) and younger patients were more commonly men (P=0.02, ANOVA) [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Patients above 40 years of age had tinnitus for longer duration than younger patients (P=0.02, ANOVA) [Table 1 and Figure 2]. The duration of symptoms was longest in patients above 60 years of age (P=0.02, ANOVA). Patients were asked to localize their tinnitus. Of those with unilateral tinnitus, 26.4 and 25.7% reported left and right-sided tinnitus, respectively; 8.9% of patients could not localize their tinnitus, describing it only as “in the head.” Of patients below 40 years of age, 54.12% had unilateral tinnitus, 38.82% bilateral tinnitus, and 7.06% poorly localized tinnitus [Table 1 and Figure 3]. Of patients aged 40–60 years, 52.63% had unilateral tinnitus, 40.67% bilateral tinnitus, and 6.70% poorly localized tinnitus. Of patients older than 60 years of age, 50.30% had unilateral tinnitus, 36.97% bilateral tinnitus, and 12.73% poorly localized tinnitus. There was no difference in location of tinnitus by age group. Unilateral tinnitus was more common than bilateral tinnitus in all the age groups (P=0.001, ANOVA). This difference was highest in the 40 to 60-year age group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by age subgroup

| <40 years | 40–60 years | >60 years | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 46 (9.8%) | 120 (25.5%) | 68 (14.5%) | |

| Female | 39 (8.3%) | 97 (20.6%) | 100 (21.3%) | 0.005* |

| Tinnitus duration (months) | ||||

| <12 | 53 (11.9%) | 102 (22.9%) | 67 (15%) | 0.02† |

| >12 | 31 (7%) | 92 (20.6%) | 101 (22.6%) | |

| Tinnitus location | ||||

| Unilateral | 46 (54.12%) | 110 (52.63%) | 83 (50.30%) | 0.801 |

| Right | 31 | 49 | 38 | |

| Left | 15 | 61 | 45 | |

| Bilateral | 33 (38.82%) | 85 (40.67%) | 61 (36.97%) | |

| Poorly localized | 6 (7.06%) | 14 (6.7%) | 21 (12.73%) | |

| Tinnitus type | ||||

| Tonal | 8 (5.8%) | 25 (18.4%) | 15 (11%) | 0.459 |

| Noise | 13 (9.6%) | 47 (34.6%) | 28 (20.6) | |

| Tinnitus onset | ||||

| Acute | 19 (67.86%) | 41 (63.08%) | 37 (61.67%) | 0.408 |

| Gradual | 9 (32.12%) | 24 (36.92%) | 23 (38.33%) | |

| Tinnitus awareness during the day (0–100%) | ||||

| Score >50 | 51 (11.6%) | 61 (13.9%) | 41 (9.3%) | 0.401 |

| Score <50 | 52 (11.8%) | 125 (28.5%) | 109 (24.8%) | |

| Pitch (VAS 0–100) | ||||

| <40 | 14 (5.3%) | 30 (11.4%) | 31 (11.8%) | 0.203 |

| >60 | 43 (16.3%) | 97 (36.9%) | 48 (18.3%) | |

| Loudness (VAS 0–100) | ||||

| >50 | 25 (6%) | 112 (26.7%) | 86 (20.5%) | 0.152 |

| <50 | 54 (12.9%) | 81 (19.3%) | 61 (14.6%) | |

| Annoyance (VAS 0–10) | ||||

| >5 | 37 (8.8%) | 125 (29.7%) | 89 (21.1%) | |

| <5 | 43 (10.2%) | 73 (17.3%) | 54 (12.8%) | 0.100 |

*= men affected more frequently than women, ANOVA †=above 12 months more common, ANOVA ANOVA: analysis of variance

Figure 1.

Gender percentage by age group

Figure 2.

Duration of tinnitus by age group

Figure 3.

Location of tinnitus by age group

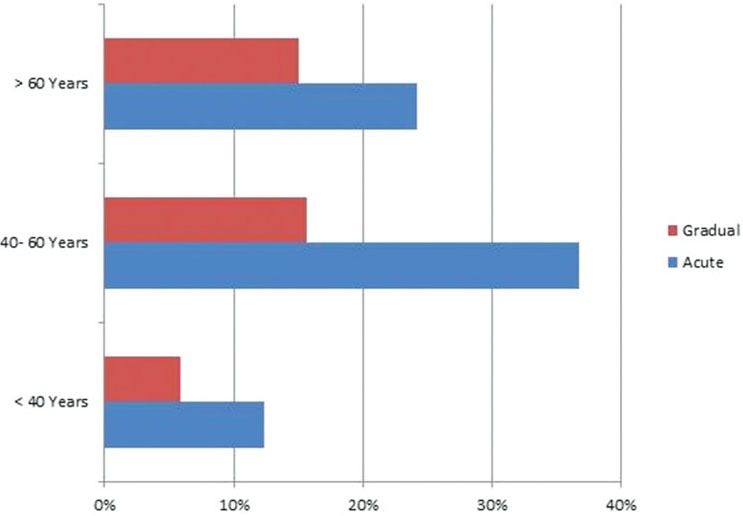

Patients described the type of sound they perceived as tonal or noise [Table 1]. More than one type of sound was reported in 56.9% of all patients, and was most common in patients less than 60 years of age. Tonal sound was reported in 43.1% of all patients. There was no difference in the type of sound reported by the age groups [Table 1]. Patients below 40 years of age most commonly reported that their tinnitus began at a mild level and increased over a period of years; 10% (n=47) had onset of their tinnitus associated with a specific event, such as trauma, an explosion, or some other loud noise; 32.14% of patients below 40 years of age had gradual onset of tinnitus and 67.86% had acute onset [Table 1 and Figure 4]; 61.67% of patients above 60 years of age had acute onset of tinnitus and 38.33% had gradual onset; and 63.08% of patients between 40 and 60 years experienced acute onset of tinnitus. There was no difference in the time of onset of tinnitus by age group. The pitch of tinnitus was subjectively assessed. Most of the patients perceived the tinnitus as high pitched (71.5%). The perception of loudness greatly varied; 53.2% of the patients thought the tinnitus was loud, with most of these patients in the above 40-year age group. These patients tended to have a high annoyance visual analogue scales (VAS) score, greater than 5 in 59.6% of these patients.

Figure 4.

Type of onset by age group

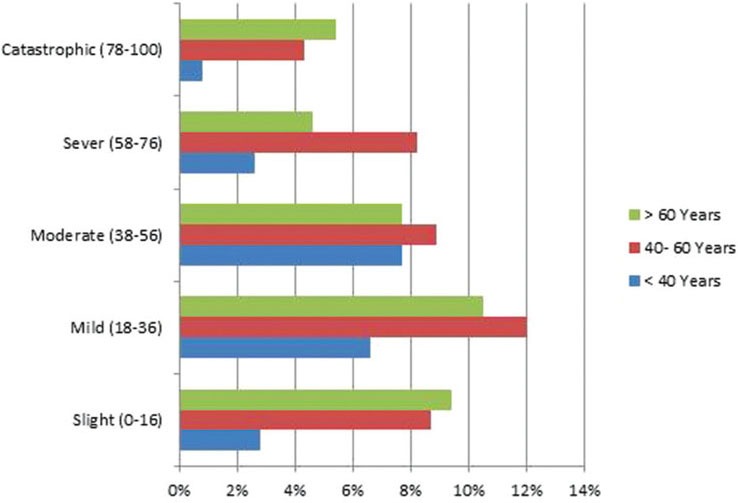

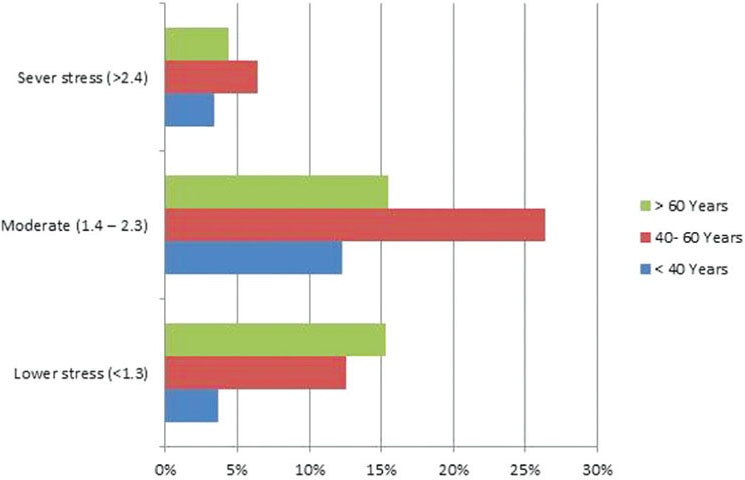

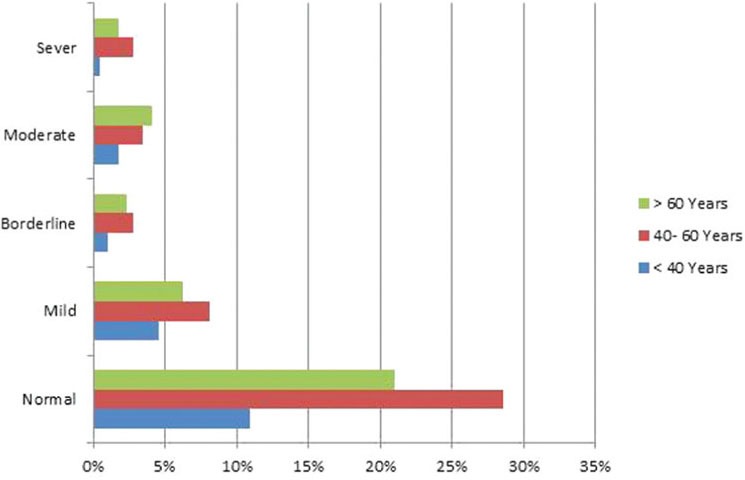

Patients rated the severity of their tinnitus using the THI scoring system [Table 2 and Figure 5]. Half (196/392) of all patients evaluated in our clinic had slight or mild tinnitus. Only 24.23% of all patients evaluated had a moderate level and 15.31% a severe level. The greatest number of patients with a mild, moderate, or severe score was found in the 40 to 60-year age group. The greatest number of patients with a catastrophic score was found in the above 60-year age group. There was no difference in tinnitus severity measured by THI by age group. The subjective severity of tinnitus was weakly correlated with BEPSI-K (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.25, P<0.001) [Table 2 and Figure 6] and BDI score (Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.48, P=0.001) [Table 2 and Figure 7].

Table 2.

Psychological characteristics by age subgroup

| <40 years | 40–60 years | >60 years | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing threshold | ||||

| 0–25 | 54 (13.3%) | 75 (18.4%) | 36 (8.8%) | 0.003† |

| 26–40 | 7 (1.7%) | 30 (7.4%) | 42 (10.3%) | |

| 41–55 | 9 (2.2%) | 24 (5.9%) | 24 (5.9%) | |

| 56–70 | 4 (1%) | 18 (4.4%) | 22 (5.4%) | |

| 71–90 | 5 (1.2%) | 42 (10.3%) | 15 (3.7%) | |

| Tinnitus severity (THI) | ||||

| Slight (0–16) | 11 (13.75%) | 34 (20.61%) | 37 (25.17%) | 0.258 |

| Mild (18–36) | 26 (32.5%) | 47 (28.48%) | 41 (27.89%) | |

| Moderate (38–56) | 30 (37.5%) | 35 (21.21%) | 30 (20.41%) | |

| Severe (58–76) | 10 (12.5%) | 32 (19.39%) | 18 (12.24%) | |

| Catastrophic (78–100) | 3 (3.75%) | 17 (10.3%) | 21 (14.29%) | |

| BEPSI stress score (Kr) | ||||

| Lower stress (<1.3) | 15 (3.7%) | 51 (12.6%) | 62 (15.3%) | 0.992 |

| Moderate (1.4–2.3) | 50 (12.3%) | 107 (26.4%) | 63 (15.5%) | |

| Severe stress (>2.4) | 14 (3.4%) | 26 (6.4%) | 18 (4.4%) | |

| BDI depression score | ||||

| Normal | 43 (10.9%) | 113 (28.6%) | 83 (21%) | 0.858 |

| Mild | 18 (4.6%) | 32 (8.1%) | 25 (6.3%) | |

| Borderline | 4 (1%) | 11 (2.8%) | 9 (2.3%) | |

| Moderate | 7 (1.8%) | 14 (3.5%) | 6 (4.1%) | |

| Severe | 2 (0.5%) | 11 (2.8%) | 7 (1.8%) |

†= greater hearing loss in patients greater than 40 years of age, ANOVA. ANOVA: analysis of variance, BDI: Beck’s depression index, BEPSI: Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version

Figure 5.

Tinnitus Handicap Inventory tinnitus severity score by age group

Figure 6.

Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument-Korean version stress score by age group

Figure 7.

Becks depression score by age group

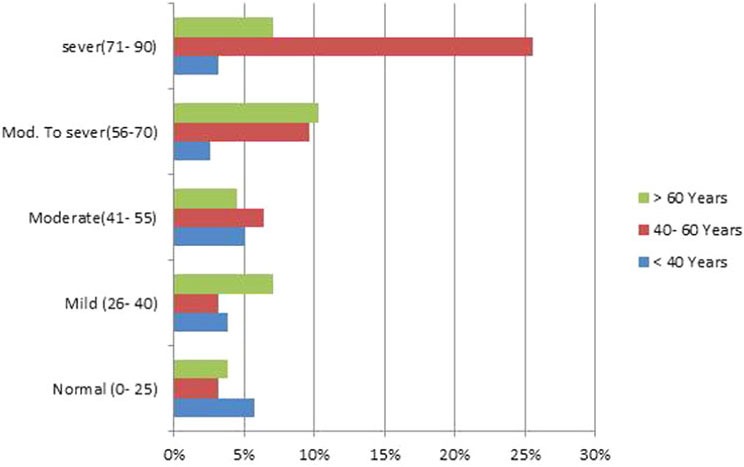

Hearing threshold in the high frequency range was evaluated [Table 2 and Figure 8]; 40.5% of all patients had normal hearing. Hearing abnormalities decreased in frequency with increasing severity. The one exception to this was the high prevalence of patients 40–60 years of age in the worst category, that is, severe.

Figure 8.

Hearing threshold in the high-frequency range by age group

DISCUSSION

Subjective tinnitus is experienced in different forms, with a wide range of severity and character. About half of patients had unilateral tinnitus. Previous reports have shown a wide range in the frequency of unilateral versus bilateral tinnitus.[3] This variation has been explained by differences in population characteristics and definitions of tinnitus and its severity. The presence of tinnitus has been reported to progressively increase with age, affecting 5% of individuals 20–30 years of age and 12% of individuals above 60 years of age. Tinnitus is not so much correlated with senescence as with concomitant HL. The prevalence of tinnitus increases to 70–85% in the hearing-impaired population;[5] 40 to 60-year-old individuals were most commonly affected, followed by individuals above 60 years of age, followed by individuals below 40 years of age. The prevalence of findings in patients 40–60 years of age may be because of this age range comprising 67.7% of patients with severe sensorineural HL.

The finding of women being affected more frequently than men in the above 60 age group may be because of their greater longevity. The location and type of onset of tinnitus in patients was similar to that in the previous reports.[6] Affected patients commonly had a gradual worsening of their tinnitus over years, starting out at a mild level and worsening over time. This could have been because of the referral patterns that occur to our clinic. Patients are generally referred to our specialty clinic from other general medicine clinics. This referral pattern could have led to patients being referred after their symptoms were observed for longer than 12 months and patients with transient tinnitus were less likely to be referred to our clinic. Also, some patients may not have been motivated to seek medical help until their symptoms worsened. This pattern was especially valid in the oldest patients, wherein some non-life-threatening symptoms were more likely to be tolerated and not evaluated.

Patients most commonly characterized the tinnitus as noise. This finding was different from the previous reports, wherein the most common tinnitus was reported to be tonal in nature.[7] This difference may be because of our use of patient description of their tinnitus. This is in contrast to the previous reports that used a predetermined category to describe the tinnitus; 16.3% of patients below 40 years of age, 36.9% between 40 and 60, and 18.3% above 60 years of age described a moderately high-pitch tinnitus on a VAS (60/100 points), similar to the previous reports;[8] 47.2% of patients above 40 years of age described moderately high loudness on a VAS (50/100 points), greater than the previous reports.[9] This loudness may be attributed to delayed referral or referral of patients with greater symptoms.

Only 12.9% of patients below 40 years of age described their tinnitus loudness as low on a VAS (less than 50 of 100 points). These patients most frequently had low psychological impact scores. A significant correlation has been reported between the loudness of tinnitus and annoyance to tinnitus, similar to our patients. This finding supports the theory that a patient's reaction to tinnitus is a complex interaction between acoustic phantom symptoms, somatic attention, and depressive symptoms;[10] 50.8% of patients who were above 40 years of age judged their annoyance from tinnitus to be moderately high on a VAS (5 of 10 points). This higher score of annoyance has been associated with increased risk for depression and anxiety,[11] similar to our patients.

The severity of tinnitus can be influenced by different factors, such as sociodemographic or tinnitus characteristics or additional health complaints; 12.8% of the patients above 40 years of age and 2.6% of patients below 40 years of age had severe tinnitus, according to THI testing, and 9.7 and 0.8%, respectively, had catastrophic tinnitus. These patients were more likely to have sleep disturbances and difficulty with daily activities. Studies in Australia,[12] the United Kingdom,[13] and Brazil[14] have not shown an association between advanced patient age and an increased incidence of catastrophic tinnitus. These differences may be because of the referral patterns found in our clinics.

Anxious and depressive symptomatology seem to be the most common sequelae of tinnitus. Marciano et al.[4] reported that 77% of consecutively screened tinnitus patients fulfilled the criteria for at least one Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) mental disorder and had elevated scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory depression, hysteria, and hypochondria scales. Patients who were above 40 years of age most frequently reported moderate stress scores (41.9%). Few patients had a high Beck depression score, with patients above 40 years of age being at greatest risk. This may be because the elderly are less able to cope with tinnitus.[15] Tinnitus severity has been reported to be positively correlated with patient depression, insomnia, and anxiety.[16] Patients did not demonstrate such an association. This lack of association in such patients may be because of the relatively large number of patients with slight or mild tinnitus (50%). The role of cognitive functioning in the development and maintenance of severe tinnitus and associated psychological distress has been well described.[17,18,19] Early intervention would appear to be required to break the cycle of tinnitus severity, psychological distress, and maladaptive coping.

CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrate that patients above 40 years of age were most commonly affected with severe tinnitus. These patients experienced more severe stress and HL than younger affected adults. It is important to evaluate affected patients for potentially modifiable risk factors for severe tinnitus and treat them. Future research should prospectively examine the relationship between patient age, risk factors for tinnitus (smoking, hypertension, and noise exposure),[20,21,22] personality traits, and mental health for their role in the development of tinnitus.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jastreboff PJ, Hazell JWP. A neurophysiological approach to tinnitus: Clinical implications. Br J Audiol. 1993;27:7–17. doi: 10.3109/03005369309077884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shargorodsky J, Curhan SG, Curhan GC, Eavey R. Change in prevalence of hearing loss in US adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304:772–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilgramm M, Rychlick R, Lebisch H, Siedentrop H, Goebel G, et al. Tinnitus in the Federal Republic of Germany: A representative epidemological study. In: Hazell JWP, editor. Proceedings of the Sixth International Tinnitus Seminar. London: The Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Centre; 1999. pp. 64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marciano E, Carrabba L, Giannini P, Sementina C, Verde P, Bruno C, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in a population of outpatients affected by tinnitus. Int J Audiol. 2003;42:4–9. doi: 10.3109/14992020309056079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meikle M, Walsh T. Characteristics of tinnitus and related observations in over 1800 tinnitus clinic patients. J Laryngol Otol. 1984;(Suppl 9):17–21. doi: 10.1017/s1755146300090053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coad ML, Lockwood A, Salvi R, et al. Characteristics of patients with gaze-evoked tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:650–4. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200109000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggermont JJ. Central tinnitus. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30(Suppl):S7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stouffer JL, Tyler RS. Characterization of tinnitus by tinnitus patients. J Speech Hear Disord. 1990;55:439–53. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5503.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernon JA, Meikle MB. Tinnitus: Clinical measurement. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:293–305. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(02)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCombe A, Bagueley D, Coles R, McKenna L, McKinney C, Windle-Taylor P. Guidelines for the grading of tinnitus severity: The results of a working group commissioned by the British Association of Otolaryngologists, Head and Neck Surgeons, 1999. Clin Otolaryngol. 2001;26:388–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2001.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crocetti A, Forti S, Ambrosetti U, Bo LD. Questionnaires to evaluate anxiety and depressive levels in tinnitus patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:403–5. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sindhusake D, Golding M, Wigney D, Newall P, Jakobsen K, Mitchell P. Factors predicting severity of tinnitus: A population-based assessment. J Am Acad Audiol. 2004;15:269–80. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Mellor D, Dawes P, Munro KJ, Moore DR, Fortnum H. Association of dietary factors with presence and severity of tinnitus in a middle-aged UK population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e 114711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto PC, Sanchez TG, Tomita S. The impact of gender, age and hearing loss on tinnitus severity. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:18–24. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jastreboff PJ. Processing of the tinnitus signal within the brain. In: Reich G, Vernon J, editors. Proceedings 5th International Tinnitus Seminar. Portland: American Tinnitus Association; 1996. pp. 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folmer RL, Griest SE, Meikle MB, Martin WH. Tinnitus severity, loudness, and depression. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:48–51. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SY, Kim JH, Hong SH, et al. Roles of cognitive characteristics in tinnitus patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:864–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.6.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rief W, Weise C, Kley N, et al. Psychophysiologic treatment of chronic tinnitus: A randomized clinical trial. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:833–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174174.38908.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson PH, Henry J, Bowen M, et al. Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H-J, Lee H-J, An S-Y, et al. Analysis of the prevalence and associated risk factors of tinnitus in adults. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figueiredo RR, de Azevedo AA, Penido Nde O. Tinnitus and arterial hypertension: A systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:3089–94. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3277-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nondahl D, Cruickshanks K, Wiley T, et al. The 10-year incidence of tinnitus among older adults. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:580–5. doi: 10.3109/14992021003753508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]