Significance

Injured tissues can self-heal. The healing process requires that tissue first migrate into the injury site and, upon collision with other expanding tissue fronts, switch from migration to cell–cell adhesion to seal the injury mechanically. The minimum signal inducing this switch is unknown due to the complexity of natural healing interfaces. We made a 3D barrier that mimicked the edge of a tissue and induced healing tissues to collide with it. When we coated the barrier with E-cadherin, a key cell–cell adhesion protein, epithelial tissues behaved as if the barrier were a tissue and stably healed against the barrier. This work reveals a key role for E-cadherin in self-healing, and an alternate way to integrate objects into tissue.

Keywords: cadherin, wound healing, biomaterial, biomimetic, collective migration

Abstract

Epithelial monolayers undergo self-healing when wounded. During healing, cells collectively migrate into the wound site, and the converging tissue fronts collide and form a stable interface. To heal, migrating tissues must form cell–cell adhesions and reorganize from the front-rear polarity characteristic of cell migration to the apical-basal polarity of an epithelium. However, identifying the "stop signal" that induces colliding tissues to cease migrating and heal remains an open question. Epithelial cells form integrin-based adhesions to the basal extracellular matrix (ECM) and E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell adhesions on the orthogonal, lateral surfaces between cells. Current biological tools have been unable to probe this multicellular 3D interface to determine the stop signal. We addressed this problem by developing a unique biointerface that mimicked the 3D organization of epithelial cell adhesions. This "minimal tissue mimic" (MTM) comprised a basal ECM substrate and a vertical surface coated with purified extracellular domain of E-cadherin, and was designed for collision with the healing edge of an epithelial monolayer. Three-dimensional imaging showed that adhesions formed between cells, and the E-cadherin-coated MTM resembled the morphology and dynamics of native epithelial cell–cell junctions and induced the same polarity transition that occurs during epithelial self-healing. These results indicate that E-cadherin presented in the proper 3D context constitutes a minimum essential stop signal to induce self-healing. That the Ecad:Fc MTM stably integrated into an epithelial tissue and reduced migration at the interface suggests that this biointerface is a complimentary approach to existing tissue–material interfaces.

Tissue–tissue interfaces play important roles in a variety of cellular processes from morphogenesis (1, 2) to wound healing or self-healing (3, 4) and to tumorigenesis (5, 6). During self-healing, two separated tissues of the same type meet and merge to heal an injury (3, 7, 8). Self-healing is typically studied in vitro by introducing a gap wound into sheets of epithelial cells (a monolayer), and following the self-healing process (9) (Fig. 1). Initial expansion into the wound site occurs by collective cell migration guided by the front-rear polarity of leader cells along the leading edge of the monolayer (3, 7, 10) (Fig. 1A). When converging tissue fronts collide, there must be a “stop signal” that inhibits further migration and promotes cell–cell adhesion (3 and table 1 in ref. 11), ultimately resulting in a transition from unstable, migratory front-rear polarity to the stable, apical-basal polarity characteristic of a simple epithelium (Fig. 1B). This process of collision, recognition, adhesion, and repolarization, called “contact inhibition of locomotion” (CIL), broadly refers to changes in cellular behavior upon collision with other cells (4). Classical CIL involves both collision and subsequent repulsion of cells and is relatively well characterized (4, 12). In contrast, self-healing is a special case of CIL and subject to different rules because wounds must heal without reopening (or involving repulsion), necessitating stable cell–cell adhesion and cell polarity transition. Here, the underlying stop signal that triggers healing is poorly understood due to the diverse cell–cell interactions at, and 3D nature of, the healing interface (3, 4, 13). Characterizing this stop signal can help us understand better how tissues recognize other tissues and, if it can be incorporated into a synthetic object, might advance the development of biomaterials that more closely resemble cells.

Fig. 1.

Overview of epithelial self-healing and the MTM. (A–C) ECM (green), E-cadherin (red), and Ecad:Fc (magenta). (A) Epithelia migrating to fill a gap wound; note lamellipodia at leading edges of the wound. (B) Postcollision healed state. (C) Substituting the MTM for a tissue. (D) Schematic of MTM functionalization with Ecad:Fc using Protein A/G and aldehyde silane (SI Materials and Methods). (E) Monolayer seeded within a temporary barrier. (F) Removal of the temporary barrier; the monolayer is allowed to expand and heal against the MTM. (G) Confocal reconstruction of MTM interface demonstrating the right angle geometry of proteins (section in F), Fibronectin-Alexa 488 (green), and Ecad:Fc-Cy5 (magenta). (Scale bar, 20 μm.)

Cell–cell adhesion has long been linked to CIL. Abercrombie and Heaysman (8) first hypothesized that cell–cell adhesion served a dual role in inhibiting migratory polarity and promoting cell–cell recognition and attachment between homotypic (mutually similar) cells and tissues (4–6, 11). Homotypic adhesive interactions often involve cadherins. Although N-cadherin is well characterized with respect to classical CIL, it commonly induces cell repulsion rather than stable adhesion (4, 14). By contrast, E-cadherin is a good candidate to contribute to the stop signal because it promotes stable attachment by directly regulating cell–cell recognition and adhesion (12), cell migration via integrin cross-talk (15), and cell polarity (16). However, technological limitations have made it difficult to demonstrate if E-cadherin simply contributes together with other proteins, or if it is minimally essential to the self-healing stop signal.

Prior reductionist assays have elucidated the role of cadherins in cell–cell junction dynamics using 2D substrates conjugated with purified N-cadherin or E-cadherin (17–21), 2D substrates copatterned with E-cadherin and extracellular matrix (ECM) (15, 22), or 3D microwells containing single cells uniformly coated with a single protein type (23, 24). However, none of these interfaces are designed to be homotypic to epithelial cells, because 2D copatterned surfaces lack the 3D geometry of a native junction and microwells coated with a single protein lack the bifunctionality of native junctions (basal ECM vs. lateral cadherin adhesions). Further, cell adhesions on 2D surfaces patterned on glass with E-cadherin exhibit atypical protrusions and large “E-cadherin plaques” (15, 21, 22) not found in native cell–cell adhesions (25). These approaches are also limited to studying single-cell responses, because the presence of multiple cells would complicate results on 2D substrates and be incompatible with single-cell, 3D microwells (15). Thus, existing 2D E-cadherin interfaces are valuable for single-cell studies, but they are not compatible with the 3D geometry and multicellular scale of epithelial tissue self-healing.

We addressed these problems by replacing one of the two tissues in the classical wound healing assay with a synthetic 3D obstacle designed to be homotypic to tissue (Fig. 1C). This “minimal tissue mimic” (MTM) recapitulated the 3D architecture of native Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial adhesions by combining a 2D basal ECM surface with a 3D vertical surface coated with correctly oriented E-cadherin extracellular domain fused at the C terminus with Fc (Ecad:Fc) MTM (Fig. 1C). Using the Ecad:Fc MTM, we showed that the 3D presentation of E-cadherin is sufficient to induce proper 3D adhesion and stop cell migration, and to cause a transition in cell polarity from front-rear to apical-basal. Thus, the Ecad:Fc MTM may provide a minimal essential stop signal for epithelial self-healing.

Results

Building the MTM.

MDCK cell monolayers are widely used as an in vitro model epithelial tissue that forms cell adhesions with a characteristic “right angle” morphology comprising a basal integrin/ECM surface and lateral E-cadherin/cell–cell contact surface (25) (Fig. 1B, Right). This orthogonal organization of cell–ECM and cell–cell adhesions, combined with the uniform distribution of E-cadherin along MDCK cell–cell contacts (25), makes the MDCK junction an attractive model system for a 3D biomimetic junction. We mimicked this organization by separately preparing ECM-coated glass (the basal surface) and 3D silicone blocks laterally functionalized with E-cadherin, and then combining the two to capture the right angle orthogonal motif of native epithelial MDCK cell junctions (Fig. 1C, Right).

MTMs were generated by cutting blocks (0.75 × 7.5 mm) from 250-μm-thick sheets of silicone by razor writing. MTMs were then coated with Protein A/G via silane linkers. Protein A/G, which binds the Fc domain of IgGs, was used to immobilize and orient purified Ecad:Fc (Fig. 1D); Ecad:Fc was expressed in mammalian HEK293 cells, and secreted with normal posttranslational modifications (N-terminal prosequence cleavage, glycosylation) characteristic of native E-cadherin. A nonadhesive (inert) control MTM was generated by substituting Ecad:Fc with Fc. MDCK cells were seeded on a fibronectin-coated glass dish (Fig. 1B, green surface) behind an inert silicone barrier (Fig. 1E, blue block), and allowed to form a monolayer over time.

Once a monolayer had formed, the Ecad:Fc- or Fc-MTM was placed adjacent to the silicone barrier (Fig. 1E, gray block). Immediately afterward, the first barrier was removed, creating an ∼300-μm gap (“wound”) between the edge of the monolayer and the MTM (Fig. 1F, blue block removed); alternately, single cells or cell monolayers were seeded directly against the MTM. To simulate wound healing, the monolayer was allowed to migrate up to the MTM overnight and then analyzed. Fig. S1 presents a low-magnification view of the system. The 3D functionalization of the MTM system was validated by confocal microscopy Z-sectioning with fluorescently labeled fibronectin (HyLite 488 label, green) and Ecad:Fc (Cy5 label, magenta). The renderings in Fig. 1G illustrate the right angle formed between basal ECM and lateral Ecad:Fc. Note that all experiments involving cells were performed with unlabeled Ecad:Fc.

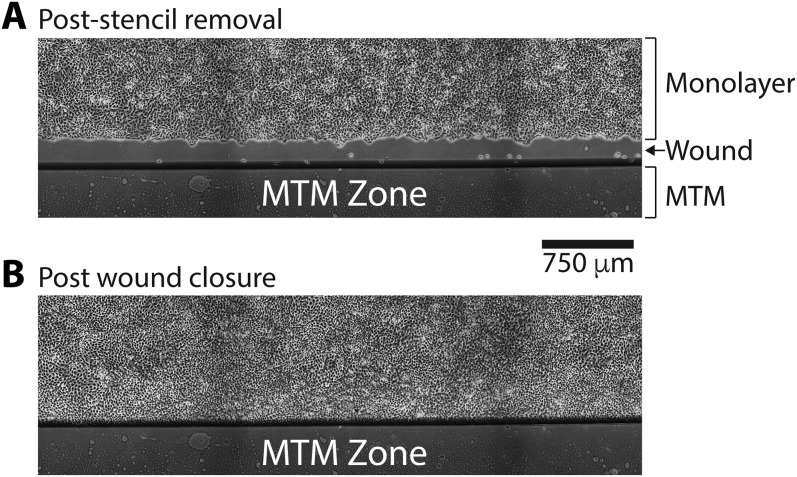

Fig. S1.

Low-magnification view of the monolayer healing against the MTM. (A) Image taken ∼1 h after stencil removal. Note the ∼250-μm gap between the tissue (Top) and the MTM wall (Bottom, in shadow). (B) Same region of monolayer after healing (∼12 h later) of the wound against the Ecad:Fc MTM. (Scale bar, 750 μm.)

MTM Junctions Capture Key Morphological Properties of Native Cell–Cell Junctions.

We first examined how single cells interacted with the Ecad:Fc MTM. Scanning confocal microscopy showed that the integrin focal adhesion protein paxillin (26) localized to the basal cell/ECM surface and not to the lateral Ecad:Fc MTM surface, whereas E-cadherin:dsRed (Ecad:dsRed) localized uniquely to the lateral, cell–Ecad:Fc MTM interface (Fig. 2 A and B). Hybrid junctions between the cell and Ecad:Fc MTM had a right angle morphology similar to native MDCK cell junctions (Fig. 2C), demonstrating correct spatial and adhesive functionality of the Ecad:Fc MTM.

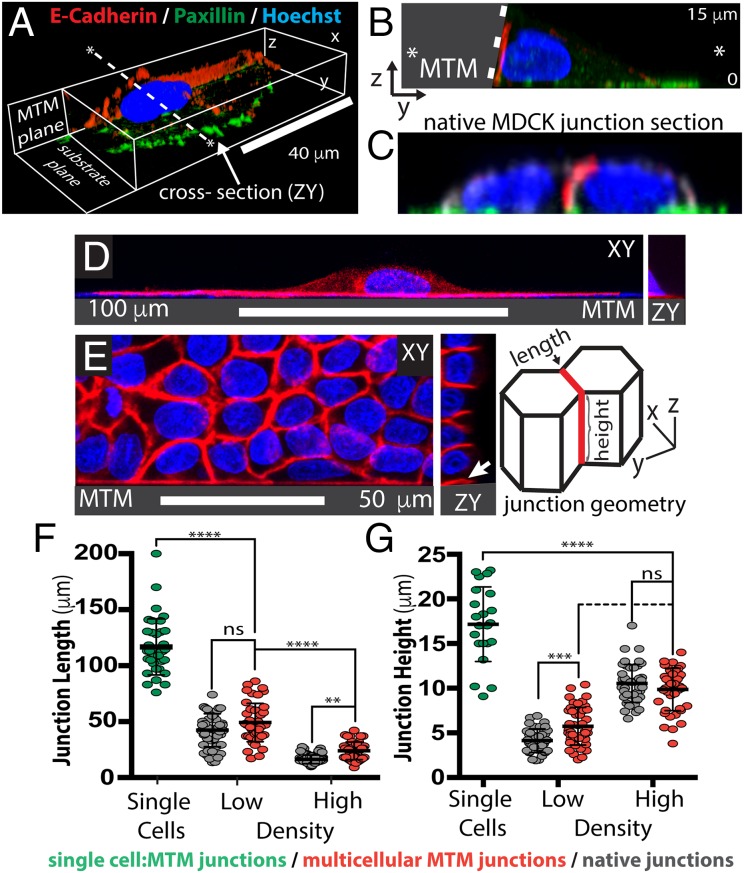

Fig. 2.

Hybrid junctions between cells and the Ecad:Fc MTM recapitulate native junction morphology. (A–E) E-cad:dsRed (red), paxillin (green), and Hoechst (blue) are shown. (A) Confocal rendering of single-cell junctioning to Ecad:Fc MTM. The “MTM plane” label indicates the plane where the cell contacts the MTM. (Scale bar, 40 μm.) (B) ZY section of A taken along the dashed line in A. The wall is shaded gray and bounded by the dashed white line; the panel height is 15 μm. (C) ZY section of native MDCK junction scaled as in B. (D) Single-cell junctioning with Ecad:Fc MTM. (Right) ZY section. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) Apparent DAPI signal along the edge of the MTM is an artifact due to autofluorescence; Ecad:dsRed signal was balanced accordingly. (E) Formation of multiple cell contacts with the Ecad:Fc MTM. (Left) XY section, sectioned as in D. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) Cartoon indicates fiducials for junction length and height measurements. (F and G) Comparisons of single-cell Ecad:Fc MTM junctions (green), monolayer Ecad:Fc MTM junctions (red), and native junctions (gray). Hybrid and native junctions are binned into high-density and low-density populations (SI Materials and Methods). (F) Junction 2D lengths. Single-cell lengths: 117 ± 25 μm (n = 36). Low density: control = 42 ± 15 μm (n = 50), hybrid = 49 ± 17 μm (n = 45). High density: control = 16 ± 4 μm (n = 78), hybrid = 24 ± 8 μm (n = 42). (G) Junction 3D heights. Single-cell heights: 17 ± 4 μm (n = 22). Low density: control = 4 ± 1 μm (n = 40), hybrid = 6 ± 2 μm (n = 45). High density: control = 11 ± 2 μm (n = 44), hybrid = 10 ± 2 μm (n = 41). ns, not significant. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Single-cell hybrid junctions with the Ecad:Fc MTM exhibited apparently unregulated expansion over the Ecad:Fc surface, reaching contact lengths of up to 200 μm (mean: 117 ± 25 μm) and heights of 17 ± 4 μm (Fig. 2D). The Ecad:dsRed distribution at hybrid lateral junctions with the Ecad:Fc MTM appeared uniform (Fig. S2A), similar to native E-cadherin cell–cell adhesions in fully polarized MDCK cells (25), and very different from the distribution of the focal E-cadherin adhesion plaques formed by cells on 2D Ecad:Fc substrates (Fig. S2B). These data indicate a significant difference in how cellular E-cadherin responds to basal (2D) vs. lateral (3D) presentation of Ecad:Fc, and that the MTM presents a more physiological interface comparable with native cell–cell adhesion.

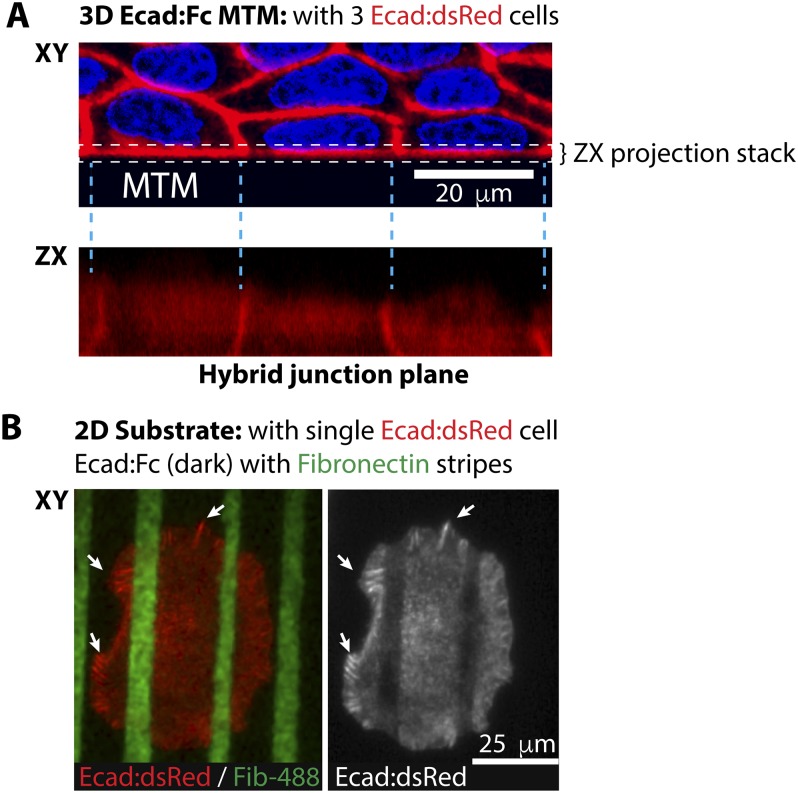

Fig. S2.

Comparison of 3D and 2D hybrid junctions. (A) XY panel shows top-down view of a monolayer forming hybrid junctions against an Ecad:Fc MTM. The ZX panel shows those hybrid junctions as they appear in the plane of the vertical wall of the MTM. The ZX reconstruction was created by ZX-projecting slices over the domain contained within the dashed white box. A consequence of this projection is that parts of the signal from intercellular junctions contiguous with the MTM are projected on top of the local hybrid junction signal. Although these regions cannot be used for quantitative purposes (SI Materials and Methods), they delineate between individual hybrid junctions. Note the apparent uniformity of the hybrid junctions of each cell. (Scale bar, 20 μm.) (B) Single cell adhering to a 2D substrate of dual Ecad:Fc/ECM copatterned substrates (6). Green stripes are Fibronectin-488, and dark zones are Ecad:Fc on glass. White arrows indicate the focal E-cadherin adhesion plaques that appear to be unique to hybrid junctions formed on 2D substrates. (Scale bar, 25 μm.)

We next explored how a monolayer interacted with the Ecad:Fc MTM. Cells at the monolayer–MTM interface simultaneously formed hybrid junctions with the Ecad:Fc MTM and native junctions with neighboring cells (Fig. 2E). We compared the 2D and 3D junction morphologies (Fig. 2E, cartoon) between hybrid and native junctions with respect to cell density (SI Materials and Methods) in confluent monolayers. At low density, control junction 2D lengths were 42 ± 15 μm and hybrid junction 2D lengths were 49 ± 17 μm; at high density, control junction 2D lengths were 16 ± 4 μm and hybrid junction 2D lengths were 24 ± 8 μm. In contrast, low-density control junction 3D heights were 4 ± 1 μm and hybrid junction 3D heights were 6 ± 2 μm; at high density, control junction 3D heights were 11 ± 2 μm and hybrid junction 3D heights were 10 ± 2 μm. Both the inverse relationship between 2D contact lengths and density (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3A) and the direct relationship between 3D contact height and density (Figs. 2G and Fig. S3B) are well characterized in native MDCK monolayers (27). Their recapitulation at hybrid junctions indicates that these junctions experience similar collective, steric regulation as occurs with native junctions. In contrast, single-cell hybrid junctions lack constraints and continue to expand. Such behaviors can be seen in Movie S1, where leader cells colliding with the Ecad:Fc MTM recruit Ecad:dsRed to the collision site and begin to expand along the wall in three dimensions. Over time, these hybrid junctions encounter neighboring hybrid junctions, eventually leading to the conditions we have quantified. Finally, all hybrid junctions at the cell–Ecad:Fc MTM interface appeared to limit junction height (Z) rather than spreading up the MTM surface, implying additional cell dimension regulation in common with both hybrid and native junctions.

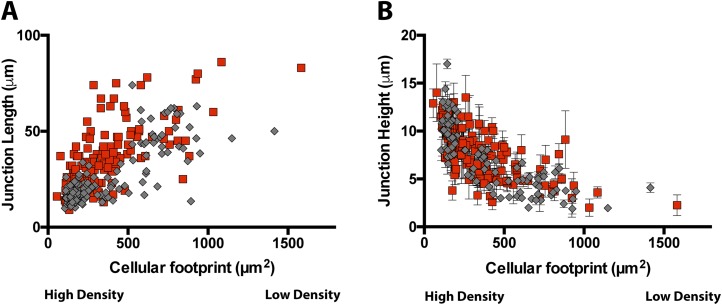

Fig. S3.

Junction morphology versus cell density. Scatterplot data comparing 2D junction lengths (A) and 3D junction heights (B) between hybrid (red, n = 135) and native (gray, n = 100) junctions with respect to cellular footprint area (varies inversely with density; SI Materials and Methods).

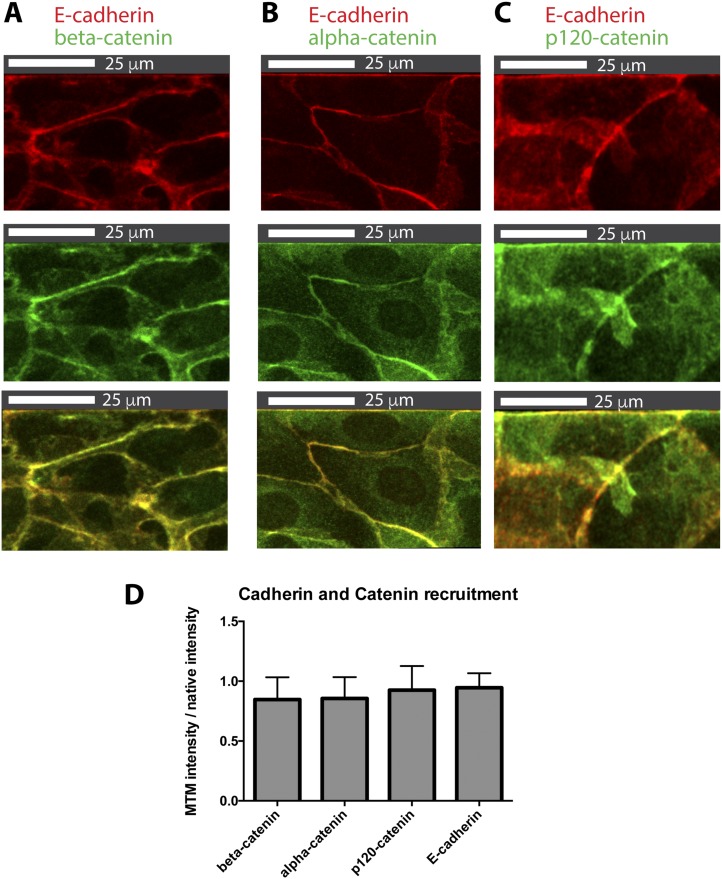

Given the morphological similarity of hybrid and native junctions, we examined the levels of cellular E-cadherin and found that the intensity of Ecad:dsRed fluorescence at hybrid junctions with the Ecad:Fc MTM reached 90 ± 13% (n = 40; SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S4) of the intensity at native cell–cell junctions within the same monolayer, indicating relatively similar levels of recruitment. We next evaluated localization and levels of the catenins in the quaternary cadherin–catenin complex: β-catenin, α-catenin, and p120-catenin. β-Catenin couples the intracellular domain of E-cadherin via α-catenin to the actin cytoskeleton, and p120-catenin regulates the stability of the E-cadherin–catenin complex at the plasma membrane (28). E-cadherin and β-catenin form an initial complex at the endoplasmic reticulum that traffics to the plasma membrane; α-catenin and p120-catenin are recruited after the E-cadherin–β-catenin complex reaches the plasma membrane (25). We found that all three catenins colocalized with cellular E-cadherin at the Ecad:Fc MTM interface (Fig. S4 A–C), and reached the following levels relative to the levels in native junctions (Fig. S4D): β-catenin = 85 ± 19% (n = 30), α-catenin = 86 ± 17% (n = 25), and p120-catenin = 93 ± 20% (n = 23). These values approach the levels of E-cadherin found in hybrid junctions (∼90%), which is consistent with the 1:1:1:1 stoichiometry observed between all three catenins and E-cadherin (28). Thus, the quaternary cadherin–catenin complex appeared to assemble properly in response to cell binding to the Ecad:Fc MTM.

Fig. S4.

Formation of the cadherin–catenin complex at the Ecad:Fc MTM. Each column represents a different marker and presents Ecad:dsRed (red), marker (green), and merge (yellow). β-Catenin (A), α-catenin (B), and p120-catenin (C) are shown. (D) Bar chart comparing relative levels of E-cadherin and catenins present in hybrid junctions normalized to their respective levels in native junctions. β-Catenin (n = 31), α-catenin (n = 26), p120-catenin (n = 24), and Ecad:dsRed (n = 39) are shown.

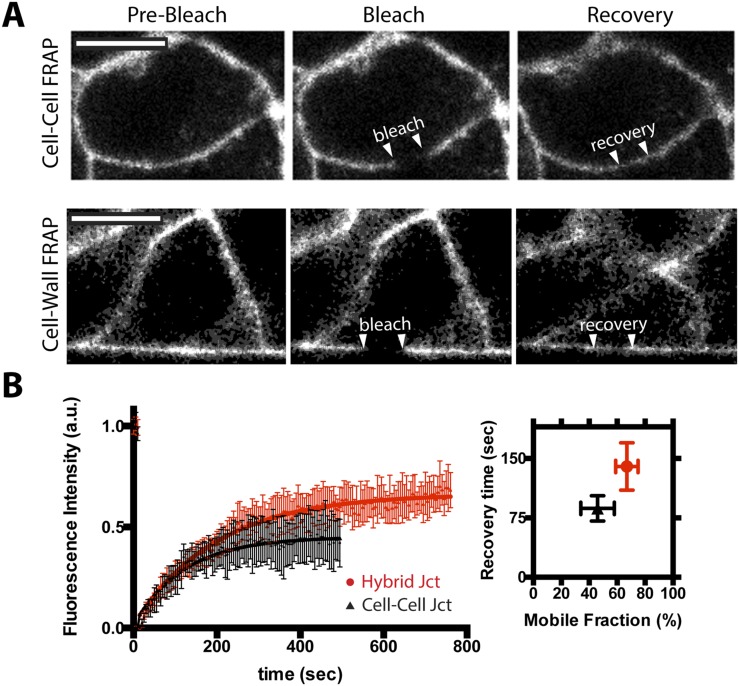

We next tested how chemical immobilization of Ecad:Fc on the MTM affected the dynamics of cellular E-cadherin, because in native cell–cell adhesions, E-cadherin proteins are mobile in the plane of the membrane and subject to internalization by endocytosis (29). Protein dynamics were assayed using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to compare Ecad:dsRed at Ecad:Fc MTM junctions and native cell–cell junctions within the monolayer. We observed a recovery time (thalf) and mobile fraction (m) of Ecad:dsRed at the Ecad:Fc MTM junction (thalf ∼135 s and m ∼ 65%) that captured similar trends to E-cadherin dynamics at native cell–cell junctions within the same monolayer (thalf ∼ 30–240 s, m ∼ 25–55%) (28, 30, 31) (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S5). The immobility of Ecad:Fc is likely responsible for the elevated mobile fraction and slight reduction in the level of cellular E-cadherin at the Ecad:Fc MTM. An increased mobile fraction has been attributed to a reduction in the formation of cadherin nanoclusters (32), and data from studies using 2D-supported membranes functionalized with E-cadherin extracellular domain demonstrated that some degree of E-cadherin mobility is essential to allow clusters to nucleate and stabilize (19).

Fig. S5.

Hybrid junctions allow E-cadherin dynamics. (A) Representative photobleaching and fluorescence recovery of Ecad:dsRed by FRAP for a cell–cell junction (Top) and cell–hybrid junction (Bottom). Photobleached zones are denoted by arrowheads. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (The FRAP protocol is described in Materials and Methods). (B) Ecad:dsRed recovery curves obtained by FRAP for native cell–cell junctions (black) and cell–hybrid junctions (red) (n = 10 for both populations); points are plotted as mean ± SD. (Right) Plot shows the overall range for the two populations of the parameters extracted from the FRAP fit. Both datasets are comparable to previously published ranges of E-cadherin mobility and recovery after FRAP at native MDCK junctions (thalf ∼ 30–240 s, m ∼ 25–55%) (29–32). a.u., arbitrary units.

The MTM Induces a Transition from Front-Rear to Apical-Basal Polarity.

We next tested the effects of the Ecad:Fc MTM on monolayer self-healing. We analyzed markers of front-rear and apical-basal polarity to determine if the monolayer–Ecad:Fc MTM interface recapitulated the transition in behavior of self-healing in native tissues. Importantly, we controlled for the effects of a purely mechanical barrier on cells by replacing Ecad:Fc with Fc to produce an inert control barrier.

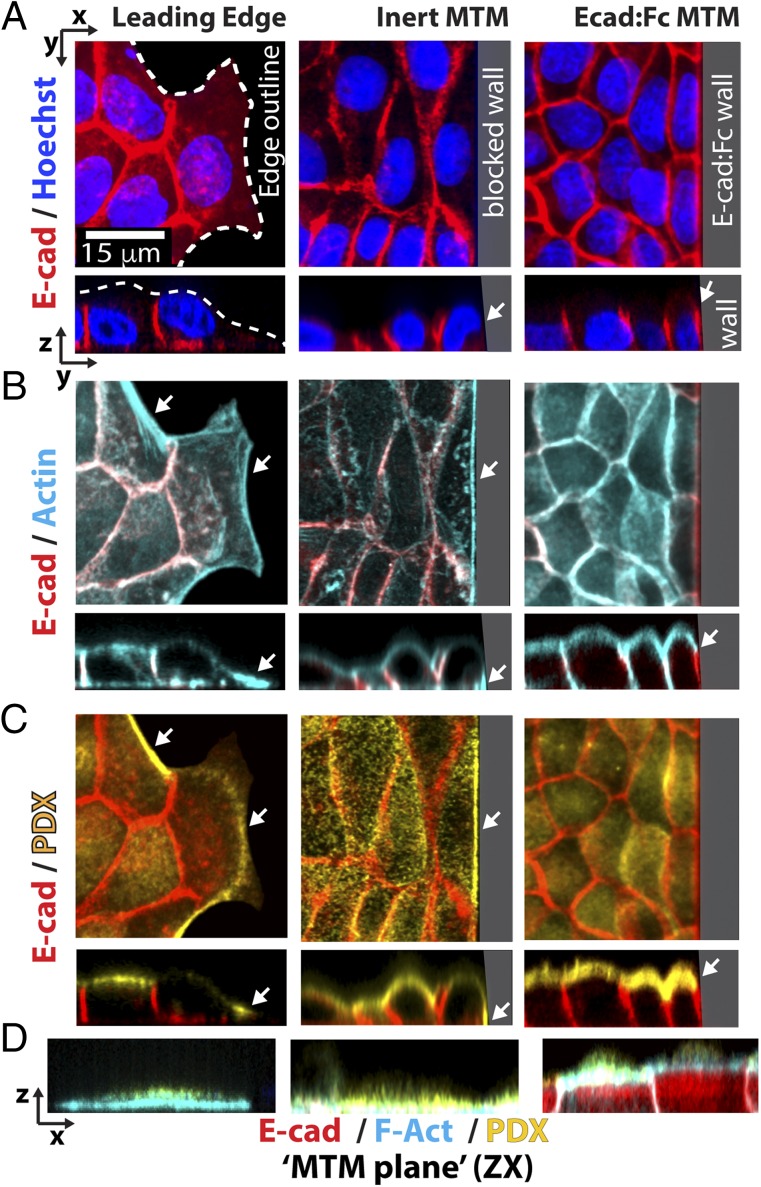

Cells at the leading edge of a migrating epithelial sheet (termed “leader cells”) serve as a reference for front-rear polarity (4). As anticipated, leader cell lamellipodia at the edge of a monolayer migrating into open space had little or no Ecad:dsRed (Fig. 3A, Left). Cells in contact with the inert control MTM also had little or no Ecad:dsRed at the monolayer–MTM interface, despite the fact that the cells were compressed against the MTM (Fig. 3A, Center). In contrast, Ecad:dsRed strongly localized to Ecad:Fc MTM interfaces (Figs. 2D and 4A, Right).

Fig. 3.

Ecad:Fc MTM interface induces epithelial polarity. Columns depict leader cells migrating into an open space (Left) or attached to an inert MTM (Center) or Ecad:Fc MTM (Right) (same monolayer as in Fig. 2E). (A–C) XY panels are projected from confocal stacks; corresponding ZY panels are depicted below each corresponding XY panel. (D) ZX sections. Within a column, each panel depicts the same region of cells. All axes are scaled equally. (Scale bar, 15 μm.) (A) Ecad:dsRed (red) and Hoechst (nuclear stain; blue) are shown. (Left) Dashed line indicates outline of lamellipodial border (also ZY section). Compressed lamellipodium (Center). Cell attachment to Ecad:Fc MTM (Right) with arrowhead in the ZY panel indicating 3D recruitment of Ecad:dsRed. (B) F-actin (green) and Ecad:dsRed (red) localization. Arrowheads (Left) indicate basal F-actin cables (ZY; Center) similar to a leader cell (Right). Note apical F-actin ring and lack of basal F-actin cables (ZY, ZX below). (C) PDX (yellow) and Ecad:dsRed (red). PDX localizes to basal leading edge (Left), similar to the leading edge control (Center). (Right) Apical PDX; compare with cells distal to MTM. (D) ZX sections showing protein localization at the outermost edge of each cell (Left and Center) (note similarities in basal F-actin and PDX localization). (Right) Hybrid junction profile against the MTM (note F-actin ring and uniform Ecad:dsRed localization). Appearance of intercellular junctions in the ZX profile results from ZX sections, including regions of native junctions contiguous with the MTM (Fig. S2A).

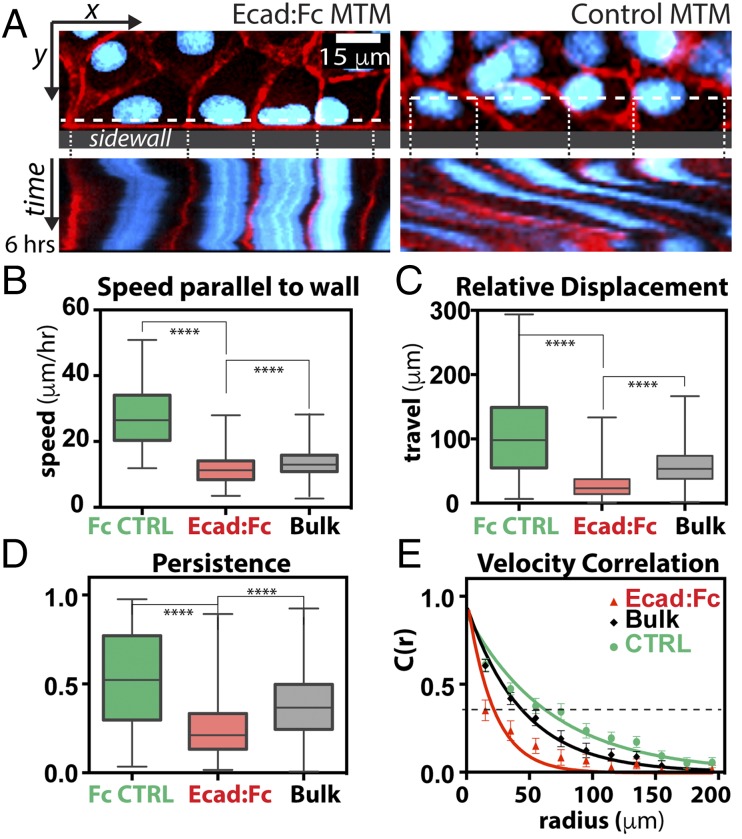

Fig. 4.

Epithelial monolayers stably adhere to the Ecad:Fc MTM. (A) Still images (Upper, XY) and corresponding 6-h kymographs (Lower, XT) of monolayers at MTMs. (Left) Behavior at Ecad:Fc MTM; cells remain relatively stationary throughout experiment. (Right) Behavior at Fc control MTM; cells tend to translocate rapidly (note the angled trajectories). Images are scaled equally. (Scale bar, 15 μm.) (B–E) Analyzed cells from three independent experiments for each condition. All plots have same color legend: Fc control (CTRL) MTM (green), Ecad:Fc MTM (red), and data from bulk monolayer far from the MTM (gray). Whiskers on box plots span minimum/maximum range. (B–D) Inert control MTM (n = 402), Ecad:Fc MTM (n = 642),and bulk tissue (n = 10,080) are shown. ****P < 0.0001. (B) Mean migration speed parallel to the MTM (mean ± SD): inert control MTM, 24 ± 9 μm⋅h−1; Ecad:Fc MTM, 11 ± 4 μm⋅h−1; and bulk tissue, 12 ± 3 μm⋅h−1. (C) Relative displacement of cells from t = 0 h to t = 12 h (mean ± SD): inert control MTM, 98 ± 68 μm; Ecad:Fc MTM, 27 ± 19 μm; and bulk tissue, 56 ± 27 μm. (D) Persistence of migration (mean ± SD): inert control MTM, 0.51 ± 0.27; Ecad:Fc MTM, 0.24 ± 0.15; and bulk tissue, 0.37 ± 0.18. (E) Average correlation length for each condition. Data points fit to C(r) = a * exp(−r/λ) with R2 > 0.92 for all fits; error bars are SD (SI Materials and Methods); dashed line at C(r) = 0.33 can be used to approximate λ visually and define the coordination distance.

We examined front-rear polarity changes at the cell–Ecad:Fc MTM interface by analyzing the F-actin cytoskeleton with phalloidin (Fig. 3B). F-actin formed pronounced basal cables along lamellipodia at the leading edge of cells in an epithelial monolayer migrating into an open space (Fig. 3B, Left; note white arrows, XY/ZY sections). Similarly, basal F-actin cables were present all along the basal-most contact between cells and the inert control MTM (Fig. 3B, Center), indicating that the front-rear polarity of F-actin at the leading edge remained at the nonadhesive physical barrier. In contrast, F-actin in cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM interface was organized in a cortical ring immediately apical to the Ecad:dsRed recruitment zone, which was characteristic of the circumferential ring of F-actin at native cell–cell junctions in the rest of the monolayer (Fig. 3B, Right; note white arrows, XY/ZY sections and ZX section for apical F-actin ring) (33); note that F-actin was not enriched basally at the cell–Ecad:Fc MTM interface, compared with the inert control MTM. The disruption of front-rear polarity at the Ecad:Fc MTM is particularly apparent when the ZY sections (Fig. 3B, Bottom) were compared. F-actin at the Ecad:Fc MTM properly assembled into an apical ring, and F-actin levels at junctions at the Ecad:Fc MTM reached 66% (±25%, n = 40) of levels within native junctions. This finding is consistent with previous data indicating that highly mobile fractions of E-cadherin can disrupt cytoskeletal attachment by reducing E-cadherin cluster formation (32). Additionally, the rigid, inactive nature of the MTM creates a different mechanical boundary condition than occurs at a native cell–cell junction, again likely affecting cytoskeletal organization and perhaps accounting for the increase in 2D hybrid junction length observed with high density cells.

Completing the transition from front-rear to apical-basal polarity requires the establishment of distinct protein localizations to the apical (noncontacting) surface. We stained cells for podocalyxin (PDX), a canonical apical marker for epithelial cells required for apical organization and 3D lumen formation (34, 35). PDX staining localized to the basal lamellipodia of cells at the leading edge of a monolayer migrating into an open space, and was absent from the lateral and apical surfaces (Fig. 3C, Left). Cells compressed against the inert control MTM also exhibited clear PDX staining at the base of the cell–MTM interface (Fig. 3C, Center; note arrowhead), compared with the apical surface staining in cells in the rest of the attached monolayer. Significantly, at the Ecad:Fc MTM interface, PDX staining was strong over the entire apical surface of the monolayer, extending up to the Ecad:Fc MTM (Fig. 3C, Right), and little or no PDX staining was observed along the length of the MTM surface or at the basal surface. Overall, PDX localization in cells junctioned to the Ecad:Fc MTM was indistinguishable from cells forming native cell–cell junctions within the same monolayer (Fig. 3C, ZY panel). This marked difference in PDX distribution between the inert control MTM and Ecad:Fc MTM is clearly observed along the length of the contact in the ZX sections (Fig. 3D). Full 3D rotation renderings of the Ecad:Fc MTM and inert control MTM are shown in Movies S2 and S3, respectively.

These results demonstrate that (i) a nonadhesive, purely mechanical barrier is insufficient to trigger a cellular recognition response by contacting cells; (ii) the epithelial cell monolayer recognized the Ecad:Fc MTM as homotypic, based on the localization of marker protein to the basal, lateral, and apical surfaces; the loss of front-rear polarity; and the formation of E-cadherin junctions; and (iii) Ecad:Fc alone is sufficient to initiate the cell–cell adhesions and polarity transition required for self-healing.

The Ecad:Fc MTM Stably Integrates into Whole-Tissue–Like Monolayers.

Fused tissues do not separate after self-healing, as first noted by Abercrombie (7), indicating the formation of a stable, homotypic tissue–tissue interface. We examined the stability of the cell–Ecad:Fc MTM interface by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy of Ecad:dsRed-expressing MDCK cells labeled with Hoechst (nuclear stain) over 12 h. Monolayers were grown within 7 × 0.75-mm Ecad:Fc- or Fc MTM-bounded reservoirs (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S6), and cellular migration at these MTM interfaces was compared with kymographs taken through the center of cells contacting the MTM. The kymographs (Fig. 4A) showed that cells forming hybrid junctions at the Ecad:Fc MTM exhibited little displacement along the MTM surface, whereas cells at inert control MTM underwent rapid displacements parallel to the MTM (Movies S3 and S4). We did not observe separation events between cells and the Ecad:Fc MTM, indicating a stable interaction, whereas such events occasionally occurred at the inert control MTM.

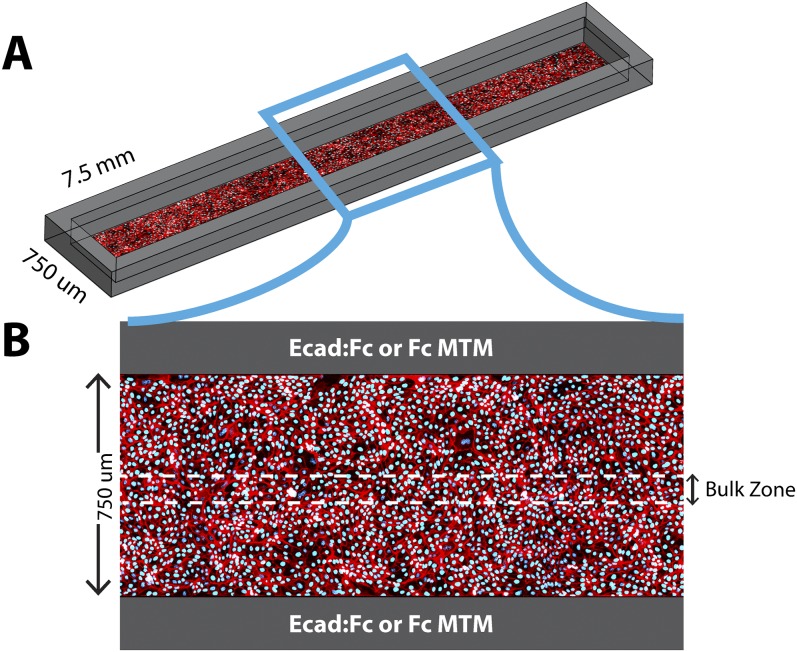

Fig. S6.

Depiction of the migration assay. (A) Three-dimensional cartoon illustrating the MTM reservoir (gray) and monolayer seeded within. (B) Close-up of the region outlined in blue. Cells analyzed were either those cells directly contacting the MTM walls or those cells within the bulk zone between the indicated dashed lines.

We quantified cell–MTM interface stability by tracking cell nuclei to generate trajectory and velocity data, and compared cell behaviors at the Ecad:Fc MTM, at the inert control MTM, and in the bulk monolayer (∼350 μm away from the MTM; SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S6). We extracted four parameters to assess the stability of cells at the MTM, beginning with the mean magnitude of the component of nuclear velocity parallel to the wall axis (V||) (Fig. 4B). The V|| of cells at the inert control MTM was twofold faster (∼24 μm⋅h−1) than the V|| of cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM or in the bulk monolayer (∼11 μm⋅h−1 and ∼12 μm⋅h−1, respectively). Thus, the Ecad:Fc MTM and nonadhesive control MTM effectively acted as a “low-slip” boundary condition and a “high-slip” boundary condition, respectively.

To characterize the distance traveled by cells along the MTM, we measured the mean relative displacement of nuclei, used to mark each cell, from their position at t = 0 h to their position at t = ∼12 h. Cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM exhibited a mean relative displacement of ∼25 μm, whereas cells in the bulk monolayer were displaced ∼55 μm and cells at the inert control MTM were displaced ∼100 μm (Fig. 4C). Hence, cells at the inert control MTM were displaced approximately fourfold more than cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM despite migrating only approximately twofold faster, indicating different forms of cell migration. We investigated this difference by measuring a third metric, persistence ϕ, defined as the ratio of the relative displacement of a cell to the total distance traversed; ϕ can range from 0 (purely erratic motion) to 1 (purely linear motion). Analysis of cells at different interfaces revealed that ϕEcad:Fc = 0.25, ϕBulk = 0.36, and ϕinert = 0.55 (Fig. 4D). These results explain the mismatch between velocity and relative displacement of cells: ϕEcad:Fc = 0.25 indicates erratic, oscillatory migration with frequent direction changes that combined to give a large overall distance traveled, but little relative displacement (∼25 μm); ϕinert = 0.55 indicates more directed migration at the inert control MTM, and hence greater relative displacement (∼100 μm); and ϕBulk = 0.36 indicates the lack of an MTM boundary condition and the likelihood of curving trajectories. Ultimately, stability of the cell–MTM interface stemmed from cell adhesion with the Ecad:Fc MTM and oscillatory, rather than directed, cell migration.

Finally, we assessed how the presence of the MTM affected the behavior of cells in monolayers distal to the MTM by calculating the directional correlation length, defined as the maximum radial distance (λ) over which the migration direction (angle) of a given cell correlated with the migration direction (angle) of its neighbors (Fig. 4E and SI Materials and Methods). The directional correlation length of cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM was up to one to two cell diameters (λ ∼ 20 μm), whereas cells at the inert control MTM were correlated with cells up to five to six cell diameters (λ ∼ 60 μm). For reference, cells within the bulk monolayer were correlated up to four to five cell diameters (λ ∼ 45 μm). Although it was expected that the effects of the rapid, directed migration at the inert control MTM would propagate relatively far from the wall, it was unexpected that the effects of the Ecad:Fc MTM would propagate over such a short distance, especially given the large size of the MTM and the “no-slip” nature of the boundary condition at the Ecad:Fc interface. Ultimately, this effect allows the Ecad:Fc MTM to integrate stably into the surrounding monolayer while perturbing cell migration to a lesser extent than does the inert control MTM.

SI Materials and Methods

Ecad:Fc Preparation and Characterization.

Ecad:Fc was purified from the culture media of HEK293 cells expressing canine Ecad:Fc as described previously (43). Briefly, HEK293 cells were expanded in standard DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C, and then switched to FBS-free DMEM 2 d before media collection to remove serum IgG. Media were collected and filtered, and Ecad:Fc was purified over a Protein A column (Thermo-Pierce). The purity and functionality of our Ecad:Fc was confirmed by SDS/PAGE and calcium-dependent aggregation of Ecad:Fc-coated agarose beads (1), whereas its specific, activating interaction with cellular E-cadherin has been confirmed via functionalization density assays (3) and nanomechanical agitation (4).

Sidewall Fabrication and Silanization.

First, silicone structures were constructed from 250-μm-thick silicone sheeting (Bisco HT-6240; Stockwell Elastomers) and cut into arrays of 1.5 × 10-mm blocks via razor writing (Cameo; Silhouette). Slight variations in the cutting process can result in variations of sidewall angles of ±10° from perpendicular. Following cutting, MTM arrays were cleaned using Scotch tape (3M) and transferred to 5-cm plastic Petri dishes (glass surfaces should be avoided during the subsequent functionalization steps). Arrays were then plasma-activated (PDC-001; Harrick Plasma) using atmospheric plasma (50 W, 45 s, 500 mtorr). If plasma is unavailable, wet activation using acid treatment may be used (44). Plasma-treated stencils were immediately silanized by immersion in a solution of 2% (vol/vol) triethoxysilylundecanal (Gelest) and 2% (vol/vol) triethylamine (Sigma) in pure ethanol (Goldshield) for 1 h (44). Excess silane solution was washed away with 100% ethanol, and the stencils were transferred to a clean 5-cm dish and subsequently baked at 85 °C for 3 h. Stencils were used within 3 d of functionalization.

Conjugating Ecad:Fc and Fc to the MTM and 2D Substrates.

Our conjugation strategy relied on first linking Protein A/G to the aldehyde silanized MTM sidewalls and then using the Fc-binding domain of Protein A/G to bind to the Fc domain on Ecad:Fc and Fc. In addition to binding Fc-conjugates stably to a surface, Protein A/G ensured that the Ecad:Fc was properly oriented away from the MTM sidewall. MTMs were prepared the day before use according to the following protocol. First, MTMs were inverted into a clean tissue-culture plastic Petri dish and incubated at 4 °C overnight in Protein A/G (350 μg/mL; Thermo-Pierce) in a sodium cyanoborohydride buffer (Coupling Buffer; Sigma) to facilitate reductive amination. After conjugation with Protein A/G, MTMs were washed three times with a phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and then washed an additional three times in PBS. MTMs were then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h in Ecad:Fc (350 μg/mL) to allow binding of the Ecad:Fc to the Protein A/G. MTMs were then washed three times in PBS and blocked with 1× BSA (Thermo-Pierce) and Fc (350 μg/mL, ab90285; Abcam) during a 1-h incubation at room temperature followed by three washes with PBS. Alternately, inert control MTMs were prepared by substituting Fc for Ecad:Fc in the previous steps. This process is summarized in Fig. 1D. The 2D substrates generated in Fig. S2B were created by silanizing glass-bottomed dishes (Mattek 3.5-cm plates), transferring fibronectin patterns via microcontact stamping, backfilling with Protein A/G, and subsequently incubating with Ecad:Fc as described above. A detailed protocol of 2D substrate preparation is described by Borghi et al. (15). Briefly, silanized glass slides were stamped with fibronectin micropatterns, backfilled with Protein A/G, and incubated in 350 μg/mL Ecad:Fc.

Cell and Monolayer Preparation.

MatTek 3.5-cm glass-bottomed dishes were coated with fibronectin (100 μg/mL, F2006; Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C before being washed three times with deionized, distilled water (DI) and air-dried. In parallel, silicone monolayer patterning stencils were prepared using the same razor-writing protocol described earlier. A typical monolayer patterning stencil consisted of a 0.75 × 7.5-mm silicone reservoir with a wall width of ∼300 μm. These stencils were placed onto fibronectin substrates and pressed into conformal contact before cells were added. This process is summarized in Fig. 1E. Alternately, functionalized MTMs can be substituted for stencils, and cells can be added to be immediately contiguous with the MTM (e.g., single-cell, density, migration characterization assays). Once monolayers had grown to confluence (SI Materials and Methods, Cell Culture and Staining), we took freshly functionalized MTMs, dried them by aspiration, and placed them adjacent to the patterning stencil. Immediately after ensuring conformal contact between the MTM and the fibronectin substrate, the patterning stencils were removed, and the system was immersed in media and returned to the cell incubator until imaging. This process is summarized in Fig. 1F. Validation of functionalization and orthogonal surface assembly was performed using Ecad:Fc-Cy5 (Cy5 label kit; GE Healthcare), Fibronectin-488 (Cytoskeleton, Inc.), and 3D confocal imaging.

Cell Culture and Staining.

All experiments were performed with MDCK-II (G-type) cells stably expressing Ecad:dsRed that were adapted for culture in customized media (low-glucose DMEM, 1 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and penicillin/streptomycin) and tested for mycoplasma (negative). Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in air. Cell seeding into stencils proceeded identical to standard cell passaging, with the exception that imaging media were used at every step of the seeding process, because trace phenol red appeared to concentrate in the silicone sidewalls and increase fluorescence background. Monolayers were seeded by adding ∼3 μL of suspended cells (2.5–7.5 million cells per milliliter depending on desired cell density) to the culture wells and allowing monolayers to form over 3 h at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. Once introduced, monolayers were allowed to collide with the MTM overnight. For immunofluorescence, samples were fixed in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde for 15 min, incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min, and blocked with goat serum and pure human Fc (crucial to stop antibody binding on Protein A/G) for 1 h. F-actin stains used Phalloidin-488 (Invitrogen), nuclei were stained using NucBlue (Invitrogen), and PDX was stained with a mouse primary antibody (35) and with a goat–anti-mouse–Cy5 secondary antibody (A10524; Invitrogen).

Image Acquisition.

Three-dimensional immunofluorescence imaging was conducted using a Leica SP8 scanning confocal microscope with a white-light laser, hybrid (HyD) photodetectors, and a tunable acousto-optical beam splitter. Custom band-passes were set for dsRed (Ecad:dsRed), Hoechst/DAPI (nuclei), Alexa 488 (phalloidin/paxillin/β-catenin), and Cy5 (PDX). Images were captured with a 63× 1.4-N.A. objective with the pinhole set at 1 Airy unit.

FRAP data are presented in Fig. S5 and were captured using the Leica SP8 scanning confocal microscope with the pinhole opened to 3 Airy units (∼2.5-μm section thickness) and a 40× 1.3-N.A. objective with a zoom factor of ∼2.5×. Sequential bleaching of Ecad:dsRed at multiple regions of interest (3 × 1 μm) was carried out using a white-light laser with dual bands at 554 nm/100% power and 560 nm/50% power to achieve rapid bleaching. Images were captured every 5 s, and total bleach time did not exceed 1.5 s. A combination of MATLAB and ImageJ was used to automate quantification of the FRAP behavior, and the resulting recovery curves were fit to a conventional single-time constant exponential of the form: , where A is the mobile fraction (percentage) and τ is the effective recovery time (seconds). FRAP imaging was carried out at 37 °C with 15 mM Hepes.

Live imaging of cell and monolayer migration dynamics was performed using a wide-field epifluorescence inverted microscope (Zeiss Observer Z1; Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Imaging was performed using 10× and 20× objectives (0.5 and 0.75 N.A., respectively), filter sets for Hoechst and dsRed, a 120-LED illumination source (X-Cite), and a Flash4 LT CMOS camera (Hammamatsu). An automated XY stage allowed multipoint imaging, and tiled images were later stitched and fused in ImageJ. Time-lapse images were captured at 15 min per frame for periods of up to 18 h in a 37 °C incubated chamber supplemented with 5% CO2.

Three-dimensional time lapses of collisions against the Ecad:Fc MTM were performed using spinning disk microscopy (Nikon Ti and Yokugawa W disk; assembled by Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Images were captured using a 63× objective (1.4 N.A., oil), filter sets for dsRed, and a Xyla CMOS camera (Andor). Stacks were captured every 20 min, and cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubated chamber with 20 mM Hepes media to maintain pH.

Image Processing and Analysis.

Image processing was performed in ImageJ and MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc.). Confocal stacks were processed using a 3D median filter to reduce background, maximum intensity projections, and contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) processing to improve visibility of the printed color images. Cross-sections (ZY) were sliced to represent junction morphology best. Typically, five slicing planes were collected at ∼350-nm spacing, and subsequently projected and processed as above to produce the cross-section image.

Calculation of volumetric Ecad:dsRed levels at hybrid junctions versus native junctions was performed with 3.5-μm-thick confocal Z-stacks around the Z midplane of junctions. A MATLAB script was written to project the stack in Z to a single XY slice and then to calculate the fluorescence intensity ratio of Ecad:dsRed, phalloidin, or catenins present in each hybrid junction normalized to the respective protein level at native junctions in the same image.

MTM and native junction morphologies were measured and related to cell density as follows. First, the footprint area of all analyzed cells was calculated with a MATLAB script using the E-cadherin fluorescence signal to segment cellular regions. Footprint area is an established method of assessing MDCK population density; footprint area varies inversely with population density due to crowding effects (27). Next, the junction lengths and heights of a given cell were measured using the segmented line tool within Fiji (ImageJ), and the resulting data were associated with the footprint area of that cell. For cells at the MTM, only the hybrid junction measured. For a given control cell, the longest junction was analyzed, both to allow for similar statistical comparison with MTM junctions and because this junction would be most sensitive to density effects. This analysis allowed us to create a database relating cell density to junction height and length (Fig. S3). Single cells were only assessed for hybrid junction length and height. The comparisons between low-density and high-density conditions (Fig. 2 F and G) were created by subsampling the density data and defining “low density” as cells with areas ≥500 μm2 and “high density” as cells with areas ≤200 μm2 (27). Data were drawn from multiple experiments, and all statistics were calculated using MATLAB and Prism 6 (Graphpad Software, Inc.).

Cellular Dynamics Analysis.

Migration data were acquired using nuclear tracking [ImageJ, Trackmate plug-in (45)], and the resulting trajectories were analyzed using custom-written MATLAB scripts. A nuclear position filter was used to identify cells making contact with MTM walls by identifying all cells within 10 μm from a wall, whereas “bulk” cells were defined as those cells within a 100-μm-wide band centered 350 μm away from opposing MTM walls. The velocity, displacement, and persistence of cells in each population were then calculated in MATLAB. Data were pooled from three independent experiments for each condition. Correlation analysis was performed using a custom-written MATLAB script and according the following equation:

where N is the total population of cells, n is the total number of neighbors at a distance of r away from cell i, and ωi,j is the angle between the direction vectors of cell i and cell j; C(r) was calculated by averaging these values for each frame of the time lapse (at least 10,000 total measurements per condition). This function was fit in MATLAB according to ; λ represents the approximate correlation length. Error bars in Fig. 4E show the SD. All statistics are reported in Fig. 4 and were calculated using MATLAB and Prism 6. Analyzed cells were drawn from three independent experiments for each condition.

Discussion

We designed the MTM to be generally accessible by requiring only inexpensive desktop equipment (SI Materials and Methods). Additionally, the MTM interface can be functionalized with any protein. This feature could be leveraged to incorporate different adhesion and signaling proteins (e.g., desmosomes, nectins, ephrins, Notch/Delta) into the MTM. Ultimately, the ability to design 3D “cell-like” objects and domains rationally in future biomaterials, such as in vitro culture substrates or implants interacting with different tissue types (e.g., percutaneous implants), may allow fundamentally new ways of interacting with tissue in vitro and in vivo (36, 37).

Here, we used the MTM to demonstrate that 3D presentation of E-cadherin appears to be a minimum stop signal sufficient to induce self-healing in healing epithelia. This finding is noteworthy, given marked differences between the MTM and native cells in the immobility of Ecad:Fc compared with cellular E-cadherin, the rigidity of the MTM itself, and the passive nature of the MTM (e.g., no active contractility). These differences likely account for the apparent lack of E-cadherin clustering, slightly lower levels of E-cadherin and catenins and reduced F-actin levels at the Ecad:Fc MTM interface, and correlation dynamics. However, they did not prevent the MTM from recapitulating the phenomenological behavior of self-healing. This finding implies that epithelial cells recognized the Ecad:Fc MTM as sufficiently “homotypic,” and, combined with the reduction in migration, these observations satisfy the criteria for the self-healing case of CIL.

The stability of hybrid junctions at the Ecad:Fc MTM (Fig. 4) may be attributed to the combined effects of the polarity transition and adhesion to the MTM. Collision with the Ecad:Fc MTM simultaneously disrupted front-rear polarity (loss of basal F-actin cables) and cell migration, and induced formation of hybrid junctions at the Ecad:Fc MTM interface (Fig. 3). By contrast, monolayers maintained front-rear polarity and exhibited rapid and directed migration at the inert control MTM, consistent with mechanical “contact guidance”-biased cell migration in response to topographic cues (38, 39). Hence, stabilization of hybrid junctions at the Ecad:Fc MTM overrode contact guidance along the MTM and inhibited migration. This behavior also occurred when single cells spread, rather than migrated, along the Ecad:Fc MTM (Fig. 2 D and E). These results differ from our previously reported studies showing that single cells on alternating 2D stripes of Ecad:Fc and collagen experienced contact guidance with no apparent reduction in the rate of migration (15). This difference highlights the importance of the 3D context of cell–cell recognition and adhesion.

The lack of directional migration at the Ecad:Fc MTM had an unanticipated consequence that may be relevant for future biomaterials. The single row of relatively stationary cells forming hybrid junctions with the Ecad:Fc MTM served as a living interface that attenuated the effects of the MTM on the migration of cells in the surrounding tissue. This “wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing” effect appears in the correlation length data: The motion of cells at the inert control MTM correlated strongly with the motion of cells many cell diameters away within the monolayer, whereas the stably adherent row of cells at the Ecad:Fc MTM allowed independent migration of cells in the monolayer adjacent to the stable row. Furthermore, the Ecad:Fc MTM resisted complete envelopment, which can occur with pure ECM scaffolds (40) and, instead, remained stably embedded in the monolayer for the duration of the experiment. These phenomena represent behaviors at a tissue–material interface that could compliment traditional ECM scaffolds and culture substrates.

That self-healing could be induced by 3D presentation of Ecad:Fc contributes to an understanding of epithelial polarity. Although some reports indicated that E-cadherin junctions are important for the establishment of apical-basal polarity in epithelia (16), others demonstrated that polarity can be established and maintained without E-cadherin adhesion (31, 41, 42). These prior results may indicate redundancy in the epithelial polarity program (34) and that establishment of an adhesion-mediated lateral surface is sufficient, but not necessary, for epithelial polarity. Results from our analysis of the inert control MTM indicate that geometry alone is not sufficient to define a lateral surface and induce the transition from front-rear to apical-basal polarity. This transition required homotypic recognition of cellular E-cadherin and the Ecad:Fc MTM, indicating that E-cadherin is sufficient to drive epithelial polarity when presented in the appropriate 3D context.

Together, our results clarify a role of E-cadherin as a stop signal in tissue self-healing and highlight the importance of the 3D context in reductionist assays. Although this approach does not capture all aspects of native wound healing (e.g., variations in protein levels, cytoskeletal reinforcement, free migration at the healed interface), the Ecad:Fc MTM biointerface represents a synthetic, cell-like object that can mimic cell–cell junctions in three dimensions and capture key phenomenological aspects of epithelial self-healing.

Materials and Methods

Full details are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Cells were cultured within polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stencils on fibronectin-coated, glass-bottomed dishes. Ecad:Fc-coated or control MTM blocks (PDMS) were secured adjacent to the stencil, and the stencil was subsequently removed to create the gap into which the monolayer expanded and collided with the MTM. All experiments were performed with MDCK II (G-type) cells stably expressing Ecad:dsRed. Cells were imaged using scanning confocal imaging (Figs. 1–3; FRAP), wide-field epifluorescence time-lapse imaging (Fig. 4), or spinning disk confocal imaging (Movie S5). Image analysis was performed with ImageJ (Fiji) and custom MATLAB codes. Statistical n and SD values are reported in figure legends or in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Life Science Research Foundation Fellowship (Howard Hughes Medical Institute sponsorship) (to D.J.C.), Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) and Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) Rubicon fellowships (to M.G.), and NIH Grant 11R35GM118064-01 (to W.J.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612208113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Foglia MJ, Poss KD. Building and rebuilding the heart by cardiomyocyte proliferation. Development. 2016;143(5):729–740. doi: 10.1242/dev.132910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood W, et al. Wound healing recapitulates morphogenesis in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(11):907–912. doi: 10.1038/ncb875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacinto A, Martinez-Arias A, Martin P. Mechanisms of epithelial fusion and repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(5):E117–E123. doi: 10.1038/35074643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayor R, Etienne-Manneville S. The front and rear of collective cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(2):97–109. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung KJ, Ewald AJ. Illuminating breast cancer invasion: Diverse roles for cell-cell interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;30:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(7):445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abercrombie M. Contact inhibition in tissue culture. In Vitro. 1970;6(2):128–142. doi: 10.1007/BF02616114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abercrombie M, Heaysman JE. Observations on the social behaviour of cells in tissue culture. II. Monolayering of fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1954;6(2):293–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(54)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang C-CC, Park AY, Guan J-LL. In vitro scratch assay: A convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson WJ. Remodeling epithelial cell organization: transitions between front-rear and apical-basal polarity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(1):a000513. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin P. Wound healing--aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayor R, Carmona-Fontaine C. Keeping in touch with contact inhibition of locomotion. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(6):319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai RA, Gopal SB, Chen S, Chen CS. Contact inhibition of locomotion probabilities drive solitary versus collective cell migration. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10(88):20130717. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theveneau E, et al. Chase-and-run between adjacent cell populations promotes directional collective migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):763–772. doi: 10.1038/ncb2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borghi N, Lowndes M, Maruthamuthu V, Gardel ML, Nelson WJ. Regulation of cell motile behavior by crosstalk between cadherin- and integrin-mediated adhesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(30):13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002662107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nejsum LN, Nelson WJ. A molecular mechanism directly linking E-cadherin adhesion to initiation of epithelial cell surface polarity. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(2):323–335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladoux B, et al. Strength dependence of cadherin-mediated adhesions. Biophys J. 2010;98(4):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz A, et al. Traction forces exerted through N-cadherin contacts. Biol Cell. 2006;98(12):721–730. doi: 10.1042/BC20060039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas KH, et al. E-cadherin junction formation involves an active kinetic nucleation process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(35):10932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513775112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoumine O, Lambert M, Mège RM, Choquet D. Regulation of N-cadherin dynamics at neuronal contacts by ligand binding and cytoskeletal coupling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(2):862–875. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert M, Padilla F, Mège RM. Immobilized dimers of N-cadherin-Fc chimera mimic cadherin-mediated cell contact formation: contribution of both outside-in and inside-out signals. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 12):2207–2219. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai J, Kam L. Rigidity-dependent cross talk between integrin and cadherin signaling. Biophys J. 2009;96(6):L39–L41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andreasson-Ochsner M, et al. Single cell 3-D platform to study ligand mobility in cell-cell contact. Lab Chip. 2011;11(17):2876–2883. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20067d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charnley M, Kroschewski R, Textor M. The study of polarisation in single cells using model cell membranes. Integr Biol. 2012;4(9):1059–1071. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Näthke IS, Hinck L, Swedlow JR, Papkoff J, Nelson WJ. Defining interactions and distributions of cadherin and catenin complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(6):1341–1352. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner CE, Glenney JR, Jr, Burridge K. Paxillin: A new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1990;111(3):1059–1068. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puliafito A, et al. Collective and single cell behavior in epithelial contact inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(3):739–744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007809109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada S, Pokutta S, Drees F, Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell. 2005;123(5):889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baum B, Georgiou M. Dynamics of adherens junctions in epithelial establishment, maintenance, and remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(6):907–917. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Beco S, Gueudry C, Amblard F, Coscoy S. Endocytosis is required for E-cadherin redistribution at mature adherens junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(17):7010–7015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811253106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Capaldo CT, Macara IG. Depletion of E-cadherin disrupts establishment but not maintenance of cell junctions in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(1):189–200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strale PO, et al. The formation of ordered nanoclusters controls cadherin anchoring to actin and cell–cell contact fluidity. J Cell Bio. 2015;210(2):333–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brieher WM, Yap AS. Cadherin junctions and their cytoskeleton(s) Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Macara IG. Organization and execution of the epithelial polarity programme. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(4):225–242. doi: 10.1038/nrm3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojakian GK, Schwimmer R. The polarized distribution of an apical cell surface glycoprotein is maintained by interactions with the cytoskeleton of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 1988;107(6 Pt 1):2377–2387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowry WE. E-cadherin, a new mixer in the Yamanaka cocktail. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(7):613–614. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Affeld K, Grosshauser J, Goubergrits L, Kertzscher U. Percutaneous devices: A review of applications, problems and possible solutions. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2012;9(4):389–399. doi: 10.1586/erd.12.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teixeira AI, Abrams GA, Bertics PJ, Murphy CJ, Nealey PF. Epithelial contact guidance on well-defined micro- and nanostructured substrates. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 10):1881–1892. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Londono C, et al. Nonautonomous contact guidance signaling during collective cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(5):1807–1812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321852111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Place ES, Evans ND, Stevens MM. Complexity in biomaterials for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2009;8(6):457–470. doi: 10.1038/nmat2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troxell ML, et al. Inhibiting cadherin function by dominant mutant E-cadherin expression increases the extent of tight junction assembly. 2000;113(Pt 6):985–996. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baas AF, et al. Complete polarization of single intestinal epithelial cells upon activation of LKB1 by STRAD. Cell. 2004;116(3):457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drees F, Reilein A, Nelson WJ. Cell-adhesion assays: fabrication of an E-cadherin substratum and isolation of lateral and Basal membrane patches. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;294:303–320. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-860-9:303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibarlucea B, Fernández-Sánchez C, Demming S, Büttgenbach S, Llobera A. Selective functionalisation of PDMS-based photonic lab on a chip for biosensing. Analyst (Lond) 2011;136(17):3496–3502. doi: 10.1039/c0an00941e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaqaman K, et al. Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. 2008;5(8):695–702. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.