Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in either of the two tumor suppressor genes TSC1 or TSC2, which encode hamartin and tuberin, respectively. Tuberin and hamartin form a complex that inhibits signaling by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a critical nutrient sensor and regulator of cell growth and proliferation. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inactivates the tumor suppressor complex and enhances mTOR signaling by means of phosphorylation of tuberin by Akt. Importantly, cellular transformation mediated by phorbol esters and Ras isoforms that poorly activate PI3K promote tumorigenesis in the absence of Akt activation. In this study, we show that phorbol esters and activated Ras also induce the phosphorylation of tuberin and collaborates with the nutrient-sensing pathway to regulate mTOR effectors, such as p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1). The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated kinase, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) 1, was found to interact with and phosphorylate tuberin at a regulatory site, Ser-1798, located at the evolutionarily conserved C terminus of tuberin. RSK1 phosphorylation of Ser-1798 inhibits the tumor suppressor function of the tuberin/hamartin complex, resulting in increased mTOR signaling to S6K1. Together, our data unveil a regulatory mechanism by which the Ras/MAPK and PI3K pathways converge on the tumor suppressor tuberin to inhibit its function.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the development of hamartomas in a variety of organs, including the brain, heart, kidneys, eyes, and skin (1). Genetic studies have mapped this disorder to the TSC1 and TSC2 genes, which encode for hamartin and tuberin, respectively (2, 3). Studies of TSC patients and animal models support the hypothesis that TSC1 and TSC2 are tumor suppressor genes that function by inhibiting cell growth and proliferation (2–4). Hamartin is a 130-kDa protein that contains a putative transmembrane domain and two coiled coil domains that are necessary for its association with tuberin (5). Tuberin is a 198-kDa protein that possesses a region of homology to the catalytic domain of Rap-family GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) at its C terminus. Recent genetic and biochemical data from several groups have shown that tuberin works as a GAP for the Ras-related GTPase Rheb (reviewed in refs. 6 and 7).

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is regulated by mitogens, nutrients, and energy levels and is known to mediate cell growth and proliferation through the regulation of at least two downstream targets, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) (reviewed in refs. 8 and 9). Genetic studies in Drosophila and biochemical studies in mammalian cells demonstrated that tuberin and hamartin act downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and Akt, but upstream of Rheb, mTOR, and S6K1. As in Drosophila, Rheb overexpression in mammalian cells greatly enhances mTOR signaling, which is efficiently inhibited by the expression of tuberin and hamartin.

Akt phosphorylates tuberin on multiple sites, including Ser-939 and Thr-1462, and thereby inhibits the tumor suppressor function of the tuberin/hamartin complex (reviewed in ref. 10). Recent data demonstrated that tuberin also senses changes in cellular energy levels through its phosphorylation by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (11). Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was also shown to induce p38- and PI3K-independent tuberin phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T consensus phosphorylation motifs (12), but the identity of the kinase that phosphorylates tuberin, the exact sites of phosphorylation, and the functional consequence of PMA-stimulated phosphorylation are unknown.

The genesis of a fully transformed tumor correlates with the improper regulation of multiple signaling systems. Consistent with the “multihit hypothesis of tumorigenesis,” these malignant tumors often have activating mutations in critical positive regulators and/or inactivating mutations in tumor suppressors that control cell growth, survival, motility, and proliferation. The PI3K/Akt pathway has been shown to regulate many of these biological processes; however, not all tumorigenic phenotypes can be linked to the activation of Akt. Previous studies have shown that other members of the AGC superfamily of basophilic kinases, the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) family, modulate targets linked to cell survival, motility, and cell division (reviewed in ref. 13). Here, we show that RSK can also signal to the mTOR nutrient-sensing pathway by directly phosphorylating the tumor suppressor protein tuberin. We identified Ser-1798 as an in vivo phosphorylation site in tuberin that is targeted by RSK1 and found that tuberin phosphorylation by RSK1 potently inhibits its ability to suppress mTOR signaling. Consistent with the notion that integration of multiple pathways is required for a fully transformed phenotype, we provide molecular evidence that tuberin represents a major signal integrator receiving multiple inputs from the Ras and PI3K pathways.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs. The plasmids encoding Flag-tagged hamartin and tuberin, and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged S6K1, wild-type RSK1, kinase-inactive RSK1, and myristoylated RSK1 (myrRSK1) have been described (14–17). The tuberin point mutants were generated by QuikChange (Stratagene). GST-S6 fusion protein was generated as described (16). The vector pCMV6-HA-Akt was obtained from Philip N. Tsichlis (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia). Flag-MEK1-DD, pEBG-Ras61L, and pEBG-Ras17N have been described (18).

Cell Culture and Transfection. HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics, and transfected by using calcium-phosphate as described (16). Cells were pretreated with wortmannin, U0126, or rapamycin (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and stimulated with either epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen) or PMA (Biomol) before harvesting. Cell lysates were prepared as described (16).

Immunoblotting and Protein Kinase Assays. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS/PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose, and all immunoblotting performed as described (16, 19). Beads from immunoprecipitations were washed twice in lysis buffer and twice in kinase buffer, and kinase assays were performed with GST-S6 as substrate (1 μg per assay), or with purified overexpressed tuberin. All samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and 32P incorporation was quantified by using a Bio-Rad PhosphorImager with imagequant software. Anti-Flag (M2) and anti-HA (12CA5) antibodies were from Sigma, all phosphospecific antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA), and anti-tuberin C-20 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Both anti-ERK1/2 and anti-avian RSK1 antibodies have been described (16).

MS. Coomassie-stained tuberin and hamartin were digested in-gel with trypsin. Extracted peptides were separated by nanoscale microcapillary HPLC as described (20). Eluting peptides were ionized by electrospray and analyzed by an LCQ-DECA XP ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA). Peptide sequence was determined by data-searching against a single-protein database for human tuberin by using the sequest algorithm (20).

Results

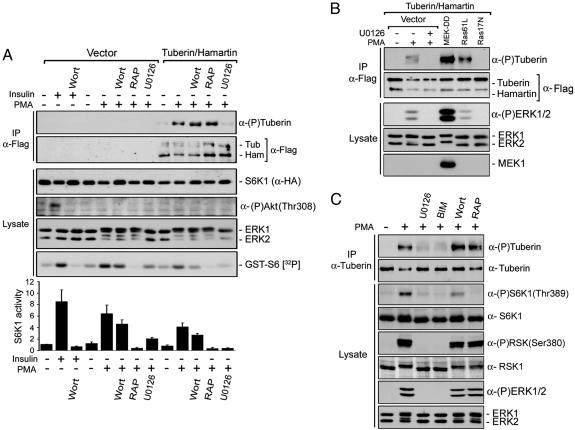

Activation of the Ras/ERK Signaling Cascade Induces Tuberin Phosphorylation Independent of Akt. To characterize the inhibitory effect of the tuberin/hamartin complex on S6K1 activity, transfected HEK293 cells were assayed for S6K1 kinase activity by using GST-S6 as substrate (Fig. 1A). Insulin was used as a control to show that PMA stimulation specifically activated the ERK-signaling cascade and that Akt was not activated. Indeed, insulin- and PMA-stimulated S6K1 activity was completely inhibited by using the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin or the MEK1/2/5 inhibitor U0126, respectively. PMA-stimulated S6K1 activity required mTOR because rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor) treatment completely inhibited S6K1 activity. As observed previously, coexpression of tuberin and hamartin decreased the basal and PMA-stimulated activity of S6K1 by ≈40%, implying that the tuberin/hamartin complex inhibits PMA-induced S6K1 activation through a PI3K-independent and MEK1/2/5-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 1.

Activation of the Ras/ERK signaling cascade induces tuberin phosphorylation. (A) S6K1 and tuberin/hamartin-transfected HEK293 cells were serum-starved for 16–18 h, pretreated with either wortmannin (100 nM; Wort), U0126 (10 μM), or rapamycin (25 nM; RAP) for 30 min, and then stimulated with either insulin (100 nM) or PMA (100 ng/ml) for an additional 15 min. Immunoprecipitated tuberin/hamartin were immunoblotted for protein levels and tuberin phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T motif [α-(P)tuberin]. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted for S6K1, Akt phospho-T308, and ERK1/2. Part of the initial lysates was used to immunoprecipitate S6K1 by using anti-HA antibodies and assayed in vitro for S6K1 kinase activity by using GST-S6 as substrate. A typical autoradiogram is shown, and results from three independent experiments are represented in a histogram as the means ± SE. (B) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with tuberin/hamartin, and constructs expressing activated MEK1 (MEK-DD) and Ras (Ras61L), or dominant negative Ras (Ras17N). Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted as in A.(C) Endogenous tuberin was immunoprecipitated from cells treated as in A and with bisindolylmaleimide I (5 μM; BIM), and immunoblotted for phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T motifs and total levels by using an anti-tuberin antibody. Total cell extracts were immunoblotted for phosphorylated ERK1/2, RSK, and S6K1, and for corresponding total proteins.

Because PMA activates several PKC isoforms and the Ras/MAPK cascade, we characterized the pathways leading to tuberin phosphorylation by using various inhibitors. Tuberin phosphorylation was analyzed by using an antibody that recognizes the phosphorylated RXRXXpS/T consensus motif, which is known to be found on both Akt and RSK substrates (12, 17, 21). Although PMA-stimulated S6K1 activity was partly inhibited by wortmannin and completely blocked by rapamycin, tuberin phosphorylation was unaffected by these inhibitors, indicating that tuberin phosphorylation was not dependent on PI3K or mTOR activity (Fig. 1 A). Conversely, PMA-induced phosphorylation of tuberin was completely inhibited by U0126, indicating that PMA stimulates a tuberin kinase located downstream of MEK1/2/5 (targets of U0126). Consistent with these results, we found that expression of both activated forms of MEK1 (MEK-DD) and Ras (Ras61L) induced significant activation of ERK1/2 and correlated with a potent stimulation of tuberin phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). Conversely, expression of a dominant negative form of Ras (Ras17N) had no effect on ERK1/2 and tuberin phosphorylation, indicating that specific activators of the MAPK/ERK pathway are sufficient to promote tuberin phosphorylation.

These results were corroborated by analyzing the phosphorylation status of endogenous tuberin immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells. Similar to what we have found by using cells transfected with tuberin and hamartin, PMA readily stimulated endogenous tuberin phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T motifs (Fig. 1C). Tuberin phosphorylation was completely inhibited by U0126 and the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM), indicating that PMA stimulates a tuberin kinase that is regulated downstream of PKC and MEK1/2/5. U0126 and BIM also inhibited PMA-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and RSK (Fig. 1C), indicating that both inhibitors effectively blocked PMA-mediated activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway. Although rapamycin completely inhibited S6K1 phosphorylation and activation (Fig. 1 A and C), both rapamycin and wortmannin had no effect on tuberin phosphorylation induced by PMA, indicating that PMA-induced S6K1 activity requires mTOR. Because PMA is known to activate PKC, which in turn stimulates the Ras/MAPK pathway, our results demonstrate that PMA stimulates a basophilic tuberin kinase located downstream of MEK1/2/5.

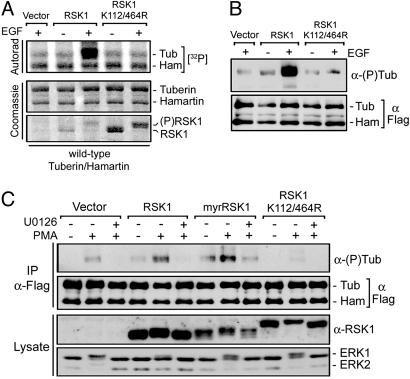

RSK1 Interacts with and Phosphorylates Tuberin in Vitro and in Vivo. Potential basophilic kinases downstream of MEK1/2/5 that may phosphorylate tuberin include members of the RSK family. To determine whether RSK1 can phosphorylate tuberin in vitro, we transiently transfected HEK293 cells with wild-type or kinase-inactive RSK1 (K112/464R) and incubated the immunoprecipitates from unstimulated or growth factor-treated cells with tuberin/hamartin complexes immunopurified from unstimulated cells overexpressing tuberin and hamartin (Fig. 2A). Although no incorporation of 32P label was seen in hamartin, incubation with growth factor-activated RSK1 specifically increased 32P incorporation in tuberin. RSK1 phosphotransferase activity was required for this effect because kinase-inactive RSK1 did not promote 32P incorporation in tuberin. In a similar experiment where the tuberin samples were analyzed by using anti-RXRXXpS/T antibodies (Fig. 2B), we found that wild-type RSK1 but not kinase-inactive RSK1 stimulated the incorporation of phosphate in tuberin at RXRXXpS/T sites in vitro.

Fig. 2.

RSK1 directly phosphorylates tuberin both in vitro and in vivo. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with either HA-RSK1, kinase inactive RSK1 (K112/464R), or control vector (pRK7), serum starved for 16–18 h, and stimulated with epidermal growth factor (25 ng/ml) for 10 min. Immunoprecipitated RSK1 was incubated with HEK293-derived Flag-tuberin/hamartin, and incubated for 15 min at 30°C in a kinase reaction containing [32P]ATP. The resulting samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and the dried gel was autoradiographed. (B) In a similar experiment, a kinase assay reaction without [32P]ATP was performed for 60 min, and samples were immunoblotted for tuberin phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T sites. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with tuberin/hamartin, and either RSK1, myrRSK1, or RSK1 K112/464R, and treated as indicated. Tuberin/hamartin immunoprecipitates and total cell extracts were immunoblotted for tuberin levels and phosphorylation, RSK1 (anti-avian), and ERK1/2. The data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments.

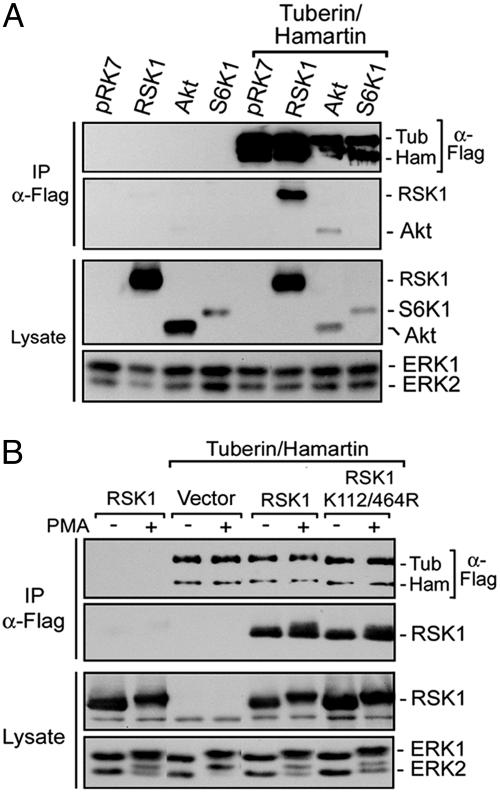

To determine whether RSK1 can phosphorylate tuberin in vivo, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with tuberin/hamartin and different RSK1 constructs, and analyzed for phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T sites after PMA treatment (Fig. 2C). Compared with control, expression of RSK1 increased both basal and PMA-stimulated tuberin phosphorylation. The RSK1-induced increase in tuberin phosphorylation was completely inhibited by U0126 treatment, indicating that RSK1 requires ERK1/2 stimulation for activity. Interestingly, a constitutively activated form of RSK1 (myrRSK1) (17) was even more potent than wild-type protein in stimulating tuberin phosphorylation, despite lower expression levels. The effect of myrRSK1 was partly insensitive to U0126, consistent with the observation that myrRSK1 does not fully require ERK stimulation for activity (22). In an attempt to inhibit endogenous RSK1 activity, HEK293 cells were transfected with a dominant-interfering mutant of RSK1, which abolished PMA-induced phosphorylation of tuberin. These results suggest that expression of kinase-inactive RSK1 disrupts endogenous RSK1-mediated phosphorylation of tuberin upon PMA stimulation. To determine whether RSK1 can interact with the tuberin/hamartin complex, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with tuberin/hamartin, and RSK1, Akt, or S6K1 (Fig. 3A). Although S6K1 could not be detected within tuberin/hamartin immunoprecipitates, RSK1 and Akt were both found as part of the complex. Interestingly, the interaction with RSK1 did not seem to be regulated by PMA, nor did it require RSK1 phosphotransferase activity (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

RSK1 and Akt interact with tuberin and hamartin in cells. (A) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with Flag-tuberin/hamartin, and either HA-tagged RSK1, Akt, or S6K1, and serum starved for 16–18 h before harvesting. Immunoprecipitates of tuberin/hamartin were immunoblotted for the presence of RSK1, Akt, and S6K1. All protein levels were determined by immunoblotting whole cell lysates. (B). HEK293 cells were transfected as above with wild-type RSK1 or kinase-inactive RSK1, and assayed for their association to tuberin/hamartin after PMA stimulation. Immunoprecipitates and total cell extracts were immunoblotted for tuberin/hamartin, RSK1, and ERK1/2.

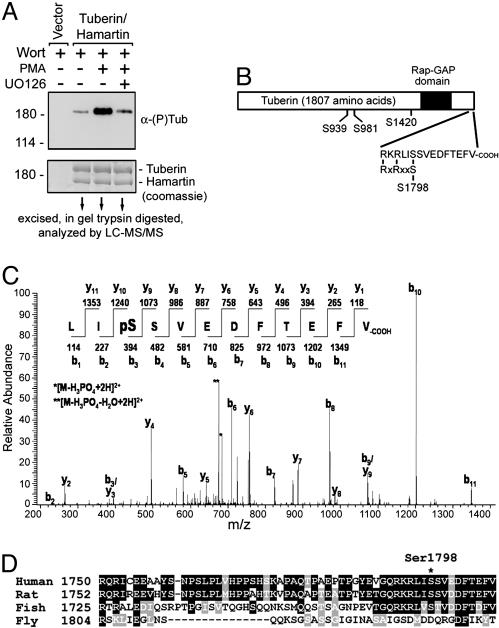

Identification of Tuberin Ser-1798 as the Major Basophilic Site Stimulated by PMA. To identify the RXRXXpS/T phosphorylation sites in tuberin stimulated by PMA, HEK293 cells were transfected with tuberin and hamartin, stimulated with PMA, and immunoprecipitated for tuberin and hamartin. Wortmannin treatment was used in all conditions to eliminate the basal PI3K/Akt-mediated inputs. After preparative SDS/PAGE and Coomassie staining, the tuberin band was cut from the gel, trypsin digested, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 4A). Four phosphopeptides containing the RXRXXpS/T sequence were identified, consisting of phosphorylated Ser-939, Ser-981, Ser-1420, and Ser-1798 residues, respectively (Fig. 4B). Phosphorylation of Ser-1798 was the most important site regulated by the MAPK/ERK pathway (see below), and the MS/MS spectrum for the doubly charged phosphopeptide is shown in Fig. 4C. Importantly, Ser-1798 as well as the basic residues located at –3 and –5 are conserved among vertebrate species, whereas the Drosophila orthologue of tuberin contains a highly acidic C-terminal region (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of tuberin phosphorylation by using MS. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged tuberin/hamartin and treated as indicated. Immunoprecipitated tuberin/hamartin were immunoblotted for tuberin phosphorylation by using 5% of the total sample. The remainder of the sample was subjected to SDS/PAGE and prepared to be analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS). (B) The positions of the identified RXRXXpS/T phosphorylation sites on tuberin are illustrated in a schematic (Ser-939, Ser-981, Ser-1420, and Ser-1798). (C) MS/MS spectrum of the C-terminal peptide containing phosphorylated Ser-1798 characterized in this study. The doubly charged precursor ion had an m/z of 733.6. (D) Shown is a primary alignment of the C termini of tuberin from human, rat, Takifugu rubripes (fish), and Drosophila (fly).

The RXRXXpS/T phosphorylation sites identified by MS were mutated to Ala residues and examined for their ability to block PMA-induced tuberin phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). HEK293 cells were transfected with hamartin and either wild-type tuberin or the various point mutants of tuberin, and examined for PMA-induced phosphorylation of tuberin. The tuberin SATA mutant (S939A/T1462A) was used in this study because mutation of Ser-939 and Thr-1462 has been shown to slightly reduce tuberin phosphorylation after PMA stimulation (Fig. 5A) (12), and we have also found that Ser-939 is phosphorylated by MS. Although Ala substitution of Ser-981 and Ser-1420 did not decrease PMA-induced tuberin phosphorylation, mutation of Ser-1798 clearly inhibited most of tuberin phosphorylation, indicating that Ser-1798 is the major phosphorylation site stimulated by PMA. Interestingly, the combination of the SATA and S1798A mutations resulted in the complete inhibition of tuberin phosphorylation upon PMA treatment.

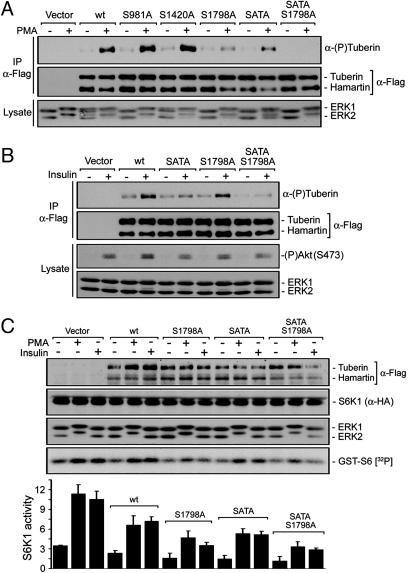

Fig. 5.

Ser-1798 is the major regulatory phosphorylation site stimulated by PMA. HEK293 cells were transfected with either tuberin wild-type or various point mutants, and treated with either PMA (A) or insulin (100 nM) (B). Immunoprecipitated tuberin/hamartin were immunoblotted for protein levels and tuberin phosphorylation on RXRXXpS/T sites. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted by using antibodies against ERK1/2 and phosphorylated Akt on Ser-473. (C) HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-S6K1 and either tuberin (wt), tuberin S1798A, tuberin S939A/T1462A (SATA), or tuberin SATA S1798A mutants, and treated as in A and B. Immunoprecipitated S6K1 was assayed for activity as in Fig. 1, and results from three independent experiments are represented in a histogram as the means ± SE. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted for tuberin/hamartin levels, S6K1, and ERK1/2.

To determine whether the PI3K/Akt and ERK/RSK1 pathways phosphorylate distinct sites on tuberin, transfected HEK293 cells were stimulated with insulin to activate the PI3K/Akt but not the ERK/RSK1 pathway (Fig. 5B). As has been shown (21), insulin treatment resulted in the potent phosphorylation of tuberin, which was mostly inhibited by mutations of Ser-939 and Thr-1462. Interestingly, mutation of Ser-1798 slightly decreased insulin-stimulated tuberin phosphorylation, and when in combination with the SATA mutations, resulted in its complete inhibition (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that Ser-939, Thr-1462, and Ser-1798 are phosphorylated after activation of both PI3K/Akt and ERK/RSK1 signaling pathways, but that Ser-1798 is the preferred RSK1 site, whereas Ser-939 and Thr-1462 are the preferred Akt sites.

Phosphorylation of Ser-1798 Impairs mTOR-Mediated Signaling to S6K1. To investigate whether tuberin phosphorylation at Ser-1798 inactivates its function, we compared the abilities of wild-type tuberin and tuberin mutants to block PMA- and insulin-induced S6K1 activation (Fig. 5C). Although tuberin inhibited PMA- and insulin-mediated S6K1 activation by ≈30%, we found that the tuberin S1798A mutant inhibited S6K1 activation by >50%, suggesting that phosphorylation of Ser-1798 normally inhibits tuberin function. As has been shown, the tuberin SATA mutant was more effective than wild-type tuberin at inhibiting S6K1 activation (Fig. 5C), but, interestingly, this mutant was even more effective when also mutated at Ser-1798. These findings demonstrate that tuberin phosphorylation at Ser-1798 and Ser-939/Thr-1462 by the ERK/RSK1 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways cooperate to inhibit tuberin function and promote mTOR-mediated signaling, as shown in the model in Fig. 6.

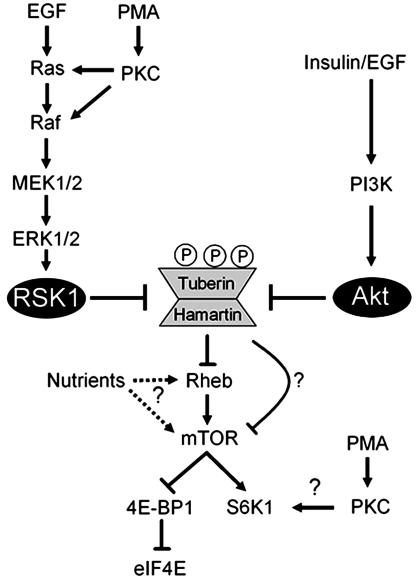

Fig. 6.

Model depicting that both ERK/RSK1- and PI3K/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of tuberin regulates mTOR signaling. Activation of both pathways results in the phosphorylation of tuberin on RXRXXpS/T consensus sites, which include Ser-939, Thr-1462, and Ser-1798.

Discussion

Deregulation of the pathways that control cell proliferation and survival is a hallmark of cancer, but the exact requirement for specific signaling pathways in oncogenic transformation remains a major question in the field. Although there are some cases where tumorigenesis was found to occur in the absence of PI3K-dependent signaling, activation of both Ras/MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways promote a stronger transformation phenotype. In this study, we show that tuberin phosphorylation is induced by specific activators of the Ras/MAPK pathway, indicating that the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex integrates signals not only from the PI3K pathway, but also from the Ras/MAPK signaling cascade (Fig. 1). We show that the MAPK-activated kinase RSK1 phosphorylates tuberin at regulatory site Ser-1798, located in the evolutionarily conserved C terminus of tuberin (Fig. 2, 3, 4). RSK1 phosphorylation of Ser-1798 inhibits the tumor suppressor function of the tuberin/hamartin complex, resulting in increased mTOR signaling to S6K1 (Fig. 5). Together, our data unveil a regulatory mechanism by which the Ras/MAPK and PI3K pathways converge on the same tumor suppressor protein to inhibit its function (see model in Fig. 6).

Here, we show that specific activation of the ERK/RSK1 pathway using the phorbol ester PMA, activated Ras, activated MEK1, or activated RSK1 led to the phosphorylation of tuberin on RXRXXpS/T consensus motifs (consensus phosphorylation sites for specific AGC family kinases including Akt and RSK1). Importantly, we found that PMA regulates the phosphorylation of both endogenous and transfected tuberin protein. We observed that RSK1 interacts with and phosphorylates tuberin both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, expression of a dominant-interfering form of RSK1 inhibits PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of tuberin, indicating that activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway stimulates RSK1-dependent phosphorylation of tuberin. Combined with the use of pathway inhibitors, our results demonstrate that RSK1 regulates tuberin phosphorylation independently of Akt. Interestingly, a recent study reported that serum-stimulated phosphorylation of tuberin is normal in embryonic fibroblasts from Akt1/Akt2 double knockout mice (23), consistent with the idea that another basophilic kinase, such as RSK1, phosphorylates tuberin in response to stimuli that activate the Ras/MAPK pathway.

Using MS, we identified four RXRXXpS/T phosphorylation sites in tuberin. Of these, Ser-1798 was found to be the primary in vivo RXRXXpS/T phosphorylation site stimulated by PMA, which was blocked by pharmacological inhibition of MEK1/2/5. Interestingly, mutation of the known Akt phosphorylation sites (Ser-939 and Thr-1462) also led to a slight reduction in PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of tuberin, indicating that RSK1 may participate in the regulation of these residues in cells. Importantly, mutation of all three sites resulted in the complete inhibition of PMA-stimulated phosphorylation of tuberin. Together, these results support the idea that the Ras/MAPK pathway converges on tuberin to promote its phosphorylation at Ser-1798, and to a lesser extent at Ser-939/Thr-1462, by activated RSK1.

Several groups have demonstrated that tuberin and hamartin function as a complex to inhibit mTOR-mediated signaling to S6K1 (14, 24–26). We found that the tuberin S1798A mutant was more effective than wild-type tuberin at inhibiting PMA- or insulin-stimulated S6K1 activity. These results are consistent with the finding that mutation of Ser-1798 decreases both PMA- and insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of tuberin. Interestingly, the triple tuberin mutant (S939A/T1462A/S1798A) inhibited S6K1 activity even more than wild-type and the tuberin S1798A mutant, indicating that tuberin phosphorylation at Ser-1798 and Ser-939/Thr-1462 function additively to inhibit tuberin. These findings are therefore consistent with a model in which mitogens activate the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways and lead to the phosphorylation and inhibition of tuberin by RSK1 and Akt, respectively. Although both PMA stimulation and expression of myrRSK1 were found to promote tuberin phosphorylation, myrRSK1 expression alone did not stimulate S6K1 activation (data not shown), suggesting that PMA activates additional pathways that are necessary for S6K1 activation. Previous studies have shown that additional PI3K-activated inputs are required for full activation of S6K1. This finding is predicted based on the observation that PKCζ participates in PI3K-mediated activation of S6K1 (27). Thus, our results suggest that tumor-promoting phorbol esters may also require inputs downstream of activated PKCs in addition to RSK1 to achieve maximal S6K1 activation.

The identification of a biochemical relationship between the tuberin/hamartin complex and the Ras/ERK/RSK1 kinase cascade may have important implications in human diseases. As suggested for the PI3K/Akt pathway, activating mutations within the Ras/MAPK pathway may lead to aberrant phosphorylation of tuberin, causing its inactivation. This result is of particular interest because Ras has been shown to be mutated in 30% of all human cancers and B-Raf is mutated in 60% of malignant melanomas (28). Interestingly, a recent study reported high levels of activated MEK1 and ERK1/2 in tuberous sclerosis complex-associated brain hamartomas (29), suggesting that MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of tuberin may lead to somatic inactivation of the tuberin/hamartin complex. Thus, elucidation of an ERK-RSK1-tuberin pathway controlling S6K1 activity will have important implications in our understanding and treatment of tuberous sclerosis and TSC-like diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Celeste Richardson, Leon Murphy, and Jeff MacKeigan for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Andrew Tee for helpful suggestions and advice in preliminary experiments leading to this study. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA46595 and GM51405 (to J.B.) and HG00041 (to S.P.G.), and a postdoctoral fellowship from the International Human Frontier Science Program Organization (to P.P.R.).

Abbreviations: RSK, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; S6K1, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; myrRSK1, myristoylated RSK1; HA, hemagglutinin.

References

- 1.Cheadle, J. P., Reeve, M. P., Sampson, J. R. & Kwiatkowski, D. J. (2000) Hum. Genet. 107, 97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbonara, C., Longa, L., Grosso, E., Borrone, C., Garre, M. G., Brisigotti, M. & Migone, N. (1994) Hum. Mol. Genet. 3, 1829–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green, A. J., Smith, M. & Yates, J. R. (1994) Nat. Genet. 6, 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito, N. & Rubin, G. M. (1999) Cell 96, 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Slegtenhorst, M., Nellist, M., Nagelkerken, B., Cheadle, J., Snell, R., van den Ouweland, A., Reuser, A., Sampson, J., Halley, D. & van der Sluijs, P. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manning, B. D. & Cantley, L. C. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 573–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwiatkowski, D. J. (2003) Cancer Biol. Ther. 2, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin, K. A. & Blenis, J. (2002) Adv. Cancer Res. 86, 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson, C. J., Schalm, S. S. & Blenis, J. (2004) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning, B. D. & Cantley, L. C. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoki, K., Zhu, T. & Guan, K. L. (2003) Cell 115, 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tee, A. R., Anjum, R. & Blenis, J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37288–37296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roux, P. P. & Blenis, J. (2004) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 320–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tee, A. R., Fingar, D. C., Manning, B. D., Kwiatkowski, D. J., Cantley, L. C. & Blenis, J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13571–13576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schalm, S. S. & Blenis, J. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roux, P. P., Richards, S. A. & Blenis, J. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4796–4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimamura, A., Ballif, B. A., Richards, S. A. & Blenis, J. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou, M. M. & Blenis, J. (1996) Cell 85, 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tee, A. R., Manning, B. D., Roux, P. P., Cantley, L. C. & Blenis, J. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 1259–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gygi, S. P., Rochon, Y., Franza, B. R. & Aebersold, R. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1720–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning, B. D., Tee, A. R., Logsdon, M. N., Blenis, J. & Cantley, L. C. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards, S. A., Dreisbach, V. C., Murphy, L. O. & Blenis, J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7470–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng, X. D., Xu, P. Z., Chen, M. L., Hahn-Windgassen, A., Skeen, J., Jacobs, J., Sundararajan, D., Chen, W. S., Crawford, S. E., Coleman, K. G. & Hay, N. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwiatkowski, D. J., Zhang, H., Bandura, J. L., Heiberger, K. M., Glogauer, M., el-Hashemite, N. & Onda, H. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potter, C. J., Huang, H. & Xu, T. (2001) Cell 105, 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tapon, N., Ito, N., Dickson, B. J., Treisman, J. E. & Hariharan, I. K. (2001) Cell 105, 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanelli, A., Martin, K. A., Toker, A. & Blenis, J. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 2921–2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downward, J. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han, S., Santos, T. M., Puga, A., Roy, J., Thiele, E. A., McCollin, M., Stemmer-Rachamimov, A. & Ramesh, V. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]