Abstract

Gastrointestinal (GI) nematode infections are an important public health and economic concern. Experimental studies have shown that resistance to infection requires CD4+ T helper type 2 (Th2) cytokine responses characterized by the production of IL-4 and IL-13. However, despite >30 years of research, it is unclear how the immune system mediates the expulsion of worms from the GI tract. Here, we demonstrate that a recently described intestinal goblet cell-specific protein, RELMβ/FIZZ2, is induced after exposure to three phylogenetically distinct GI nematode pathogens. Maximal expression of RELMβ was coincident with the production of Th2 cytokines and host protective immunity, whereas production of the Th1 cytokine, IFN-γ, inhibited RELMβ expression and led to chronic infection. Furthermore, whereas induction of RELMβ was equivalent in nematode-infected wild-type and IL-4-deficient mice, IL-4 receptor-deficient mice showed minimal RELMβ induction and developed persistent infections, demonstrating a direct role for IL-13 in optimal expression of RELMβ. Finally, we show that RELMβ binds to components of the nematode chemosensory apparatus and inhibits chemotaxic function of a parasitic nematode in vitro. Together, these results suggest that intestinal goblet cell-derived RELMβ may be a novel Th2 cytokine-induced immune-effector molecule in resistance to GI nematode infection.

More than 1 billion people worldwide are infected with one or more species of gastrointestinal (GI) nematode parasites (1), and within the livestock industry, reduced productivity and the need for repeated drug treatment impose a heavy economic burden (2, 3). Evidence of immunity to GI nematode infection in livestock and the association of type 2 immune responses and host resistance in human populations (4, 5) suggest that long-term immunologic intervention strategies are an achievable goal. The importance of CD4+ T helper (Th) cells in regulating immunity to GI nematode infection has been demonstrated formally in murine model systems. Although Th1-associated cytokines, including IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-γ, can inhibit protective immunity to GI nematode infection, T helper type 2 (Th2) cells (defined by their production of IL-4, IL-9, and IL-13) mediate expulsion of live worms and host protective immunity (reviewed in refs. 6–8).

However, the Th2 cytokine-induced immune effector mechanisms that mediate expulsion of GI nematodes remain unknown. For example, worm expulsion can occur in the absence of classical effector mechanisms associated with Th2 cytokine responses, such as antibody production, eosinophilia, and mastocytosis (9–11). Goblet-cell hyperplasia is a dominant and well documented characteristic change in the GI tract associated with Th2 cytokine responses and expulsion of nematodes (12–15). However, the role of this cell population in immunity to nematodes has received little attention.

Only a limited number of intestinal goblet cell-specific proteins have been identified. Recently, we described a goblet cell-specific protein, RELMβ/FIZZ2 (16), a member of the resistin-like molecules/found in inflammatory zone (RELM/FIZZ) gene family (17, 18). This family of proteins, composed of four members (RELMα, RELMβ, RELMγ, and resistin), exhibits unique distribution patterns in different mammalian species. For instance, resistin is expressed in adipocytes and regulates glucose metabolism in rodents, whereas RELMα and RELMγ are expressed widely in multiple tissues (17, 19–22).

By contrast, expression of RELMβ is tightly restricted to intestinal goblet cells, from where it is secreted apically into the intestinal lumen, and it is highly conserved in all examined mammalian species (18). However, the functions of RELMβ remain unknown. In this article, we demonstrate that goblet cell-specific RELMβ expression is dramatically up-regulated in the GI tract after exposure to nematode infections. Expression of RELMβ is controlled by Th2 cytokines and is coincident with host protective immunity. Furthermore, RELMβ binds specific structures in the nematode cuticle associated with neuronal structures that may impair pathogen chemosensory functions. Together, these results suggest an immune effector function for RELMβ against GI nematode pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Pathogens. AKR, BALB/c, IL-4–/–, and IL-4Rα–/– mice (The Jackson Laboratory and B & K Universal, Hull, U.K.) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Pennsylvania or a conventional environment at the University of Edinburgh. The maintenance, infection, and recovery of Trichinella muris, Trichuris spiralis, and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis were as described in refs. 23–25. In some studies, mice received daily i.p. injections of recombinant IL-13 (rIL-13) (10 μg) (Wyeth) on days 12–16 after infection. All experiments were performed under the guidelines of either the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care and Use Committee or the U.K. Home Office Animals Scientific Procedures Act of 1986.

Sample Collection, mRNA Analysis, and Immunohistochemistry. Freshly isolated samples of colon or jejunum (starting 10 cm from the pylorus) were snap frozen for RNA isolation or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding. Quantification of mRNA expression for goblet cell-specific genes, normalized to GAPDH levels, was performed on an ABI 7000 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems). The oligonucleotide primer sequences for murine RELMβ, Muc2, TFF3, and GAPDH have been described (16). Paraffin-embedded sections were cut, dewaxed in ethanol, rehydrated in 10 mM citric acid buffer (pH 6.0), and microwaved for 13 min and 30 sec. The sections were incubated with an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody for murine RELMβ at a 1:500 dilution overnight at 4°C and then incubated with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, followed by detection of horseradish peroxidase as described (16).

Cell Culture. LS174T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured under the described conditions. rIL-4, rIL-13, and IFN-γ were purchased from R & D Systems and used to stimulate LS174T cells for the durations and at the concentrations described in the figure legends.

Protein Isolation and Immunoblotting. The anti-mRELMβ antibody and its use in immunoblotting, as well as the conditions used to isolate stool proteins, have been described (16).

Whole-Mount Fixation of Nematodes and Immunolocalization of RELMβ. T. muris worms were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 3–5 min, washed in PBS, transferred to 100% ethanol, mounted on positively charged slides (SuperFrost Plus, Fisher Scientific), and air dried before returning to PBS. Slides were then boiled in 10 mM citric acid buffer, washed in PBS, blocked with protein blocking agent (Coulter Immunotech), and incubated overnight at 4°C with the anti-RELMβ antibody. Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was applied, and slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes) and mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Specimens were imaged with an E600 fluorescent/differential interference contrast microscope (Nikon), which was equipped to take optical sections in Z series. Stacked optical sections were combined to produce a 2D representation of 3D space (i.e., ×20 fluorescent image) and rotated to indicate the depth from the surface of the stained entities (i.e., ×100 fluorescent image rotated ≈80°). The specificity of this immunostaining was verified by experiments demonstrating complete blocking of immunostaining when RELMβ antiserum was preincubated with RELMβ immunogen peptide, as well as the inability to block immunostaining when this antiserum was preincubated with three irrelevant peptides (clusterin, villin, and HNF-3β). Strongyloides stercoralis parasitic infective third-stage larvae (L3i) were preincubated with rRELMβ (500 ng/ml) for 30 min at room temperature before fixation and processing as described above.

Chemotaxis Studies. Infective S. stercoralis L3i parasitic larvae were reared in charcoal coprocultures and incubated in either control protein (rIL-4; R & D Systems) or rRELMβ (Pepro-Tech, Rocky Hill, NJ) (50 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature. Chemosensory function of L3i was then assessed according to a protocol modified from Ward (26). In brief, L3i were applied to agar plates containing a preestablished concentration gradient of aqueous canine skin extract (27). Numbers of worms in attractant wells were determined every 4 min for 20 min.

Results

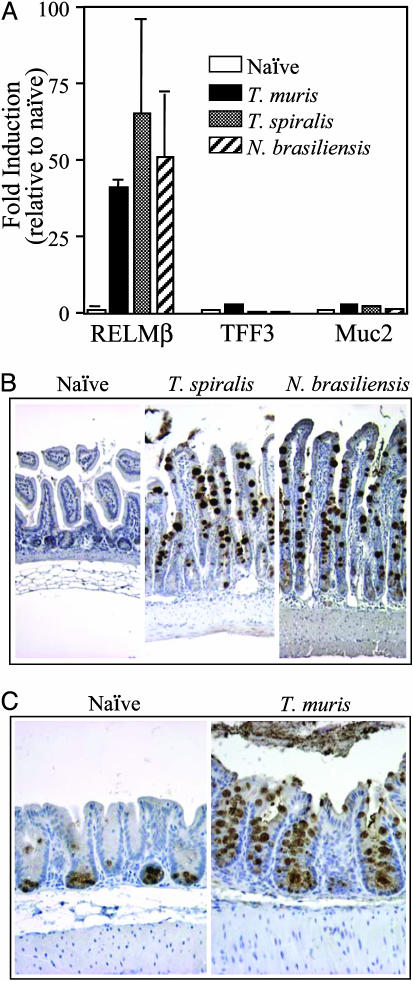

To determine whether RELMβ expression is associated with Th2 cytokine responses and goblet-cell hyperplasia that occur after GI nematode infection, we examined expression in mice infected with various GI nematode parasites. After infection with Tri. spiralis, N. brasiliensis, or T. muris, high levels of RELMβ mRNA (Fig. 1A) and protein (Fig. 1 B and C) were induced in the intestinal mucosa. In all infections, there was a marked goblet-cell hyperplasia (Fig. 1 B and C), and immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that RELMβ protein expression was restricted to goblet cells in both the small intestine (Fig. 1B) and colon (Fig. 1C). Studies have shown that the kinetics of maximal Th2 cytokine production and worm expulsion depends on the species of GI nematode (6, 7). Robust expression of RELMβ was coincident with the production of Th2 cytokines and worm expulsion after exposure to Tri. spiralis, N. brasiliensis, or T. muris (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

GI nematode infections induce high-level expression of RELMβ. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression for RELMβ, TFF3, and Muc2 in the GI tract of BALB/c mice infected with T. muris (colon, day 16 after infection), Tri. spiralis (small intestine, day 14 after infection), or N. brasiliensis (small intestine, day 10 after infection). (B) Immunohistochemistry for RELMβ in the small intestine of naïve and Tri. spiralis- or N. brasiliensis-infected BALB/c mice. (C) Immunohistochemistry for RELMβ in the colon of naïve and T. muris-infected BALB/c mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments containing three to four mice in each experimental group.

To investigate whether infection-induced RELMβ expression was due to a general enhancement in expression of goblet cell-specific mRNAs, expression levels of two other dominant goblet cell-specific genes, Muc2 and TFF3 (16), were analyzed. Critically, there was only minimal induction of either Muc2 or TFF3 (2- to 3-fold) after infection with Tri. spiralis, N. brasiliensis, or T. muris, compared with a 30- to 70-fold induction of RELMβ (Fig. 1 A). Low-level induction of Muc2 after N. brasiliensis infection is consistent with a previous report (28). These studies demonstrate that RELMβ was the only goblet cell-specific gene to exhibit robust induction after nematode infection. Indeed, transcriptome analysis has shown that RELMβ is the only goblet cell-specific gene that is strongly induced after GI nematode infection in murine hosts (46). Furthermore, after infection with Toxoplasma gondii, an intracellular protozoan pathogen that induces Th1 cytokine responses in the GI tract (29), RELMβ expression was not induced (D.A., G.D.W., and C. A. Hunter, unpublished data), demonstrating that induction of RELMβ is not a generic response to GI pathogens but is restricted to GI nematode infections that induce dominant Th2 cytokine responses. Consistent with Th2 cytokine-dependent expression of RELMβ, studies have revealed that expression of RELMα can be induced by Th2 cytokines (17, 19).

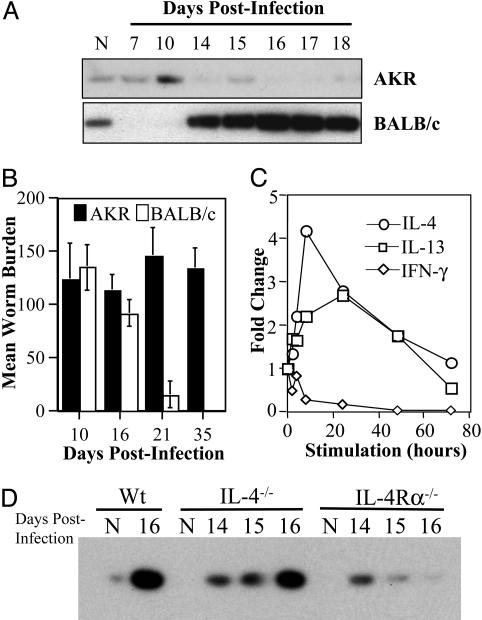

Murine trichuriasis is unique among GI nematode model systems, being the only entirely enteric infection in which reciprocal activation of Th cell subsets correlate with acute and chronic infection. Thus, in genetically susceptible strains such as AKR mice, Th1-associated cytokines (IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-γ) promote parasite persistence, whereas the production of Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) in resistant BALB/c mice is required for worm expulsion and host protective immunity (6). The genetic predisposition to infection observed between different inbred mouse strains reflects a similar pattern of predisposition observed in outbred human and livestock populations. By using infection of mice with T. muris as a model, we sought to determine whether resistance or susceptibility to infection was associated with differential expression of RELMβ. Induction of RELMβ expression was observed only in infected BALB/c mice (Fig. 2A) in a temporal fashion corresponding closely with the induction of a robust Th2 cytokine response (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and worm expulsion (Fig. 2B). By contrast to BALB/c mice, T. muris infection of AKR mice was characterized by the production of IFN-γ (Fig. 5), no induction of RELMβ (Fig. 2 A), and the presence of persistent worms beyond day 35 after infection (Fig. 2B). In addition, although RELMβ was the only goblet cell-specific gene induced after infection of BALB/c mice, there was no increase in any analyzed goblet cell-specific genes (RELMβ, Muc2, or TFF3) in colonic tissue isolated from T. muris-infected AKR mice (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Expulsion of T. muris is associated with production of Th2 cytokines and the induction of RELMβ expression. (A) Immunoblots for RELMβ protein isolated from the stool of naïve or T. muris-infected AKR and BALB/c mice. (B) Analysis of T. muris worm burden in AKR and BALB/c mice on various days after infection. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RELMβ mRNA expression in LS174T cells stimulated with either IL-4, IL-13, or IFN-γ for the indicated times (levels normalized to RELMβ expression in unstimulated LS174T cells were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1). (D) Immunoblots for RELMβ protein isolated from the stool of naïve (N) or T. muris-infected wild-type BALB/c (Wt), IL-4–/–, and IL-4Rα–/– mice collected on various days after infection.

These in vivo analyses demonstrated that induction of RELMβ was coincident with expression of Th2, but not Th1, cytokine responses. To determine whether Th1 and Th2 cytokines could directly induce expression of RELMβ in the intestinal epithelium, we examined their effects on a goblet cell-like intestinal epithelial cell line (LS174T), which is known to express RELMβ (30). Similar to the response observed in vivo, RELMβ mRNA expression was induced by either rIL-4 or rIL-13 and inhibited by IFN-γ (Fig. 2C), supporting a role for Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines in directly regulating RELMβ expression in goblet cells.

IL-4 and IL-13 signal through the IL-4Rα chain and activate STAT6-dependent genes (31). To investigate the contribution of IL-4 versus IL-13 in regulating expression of RELMβ, BALB/c IL-4–/– and IL-4Rα–/– were infected with T. muris. Although infected IL-4–/– mice exhibited robust induction of RELMβ similar to that observed in WT mice, there was minimal RELMβ expression in infected IL-4Rα–/– (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that IL-4-independent, but IL-4Rα-dependent (via IL-13), mechanisms are critical in RELMβ induction. Consistent with these observations, studies have shown that expulsion of T. muris in BALB/c IL-4–/– mice is IL-13-dependent and that IL-4Rα–/– mice are susceptible to chronic infection (32). The existence of STAT6 binding sites in the RELMβ promoter (16) supports a role for IL-4- and IL-13-mediated STAT6 activation and induction of RELMβ. Further, our previous studies demonstrating a role for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and NF-κB in immunity to T. muris (25, 33), coupled with the presence of NF-κB binding sites in the RELMβ promoter (16), suggest TNF-induced NF-κB activation may be a critical pathway in eliciting optimal effector RELMβ responses in the GI tract.

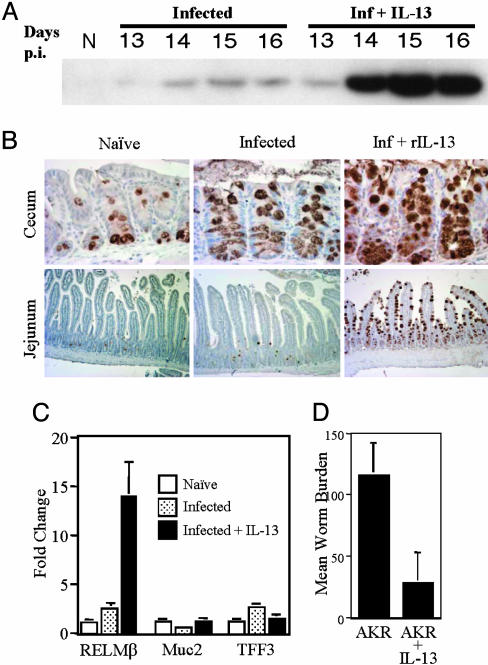

Studies have shown that rIL-13 administration can induce expulsion of T. muris in normally susceptible AKR mice (32). To determine whether IL-13-induced worm expulsion was associated with induction of RELMβ, rIL-13 was administered i.p. to T. muris-infected AKR mice. There was a dramatic up-regulation of RELMβ protein expression in the stool after treatment (Fig. 3A). Induction of RELMβ was restricted to intestinal goblet cells (Fig. 3B) and was induced both at the site of infection, in the cecum, and ectopically in the jejunum (Fig. 3B). These results identify RELMβ as an IL-13-induced gene in the GI tract. Moreover, induction of RELMβ was remarkably specific, occurring without significant induction of other goblet cell-specific genes (Fig. 3C). IL-13-induced expression of RELMβ in infected AKR mice was also associated with a significant reduction in worm burden (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Administration of rIL-13 results in the induction of RELMβ expression and expulsion of T. muris in AKR mice. (A) Immunoblots for RELMβ protein isolated from the stool of naïve (N) or T. muris-infected AKR mice that received either PBS or rIL-13 (10 μg) by i.p. injection. Days p.i., days after injection. (B) Immunolocalization of RELMβ in the cecum and jejunum (small intestine) of naïve and T. muris-infected AKR mice that received either PBS or rIL-13 (day 16 after infection). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of RELMβ, TFF3, and Muc2 in the colon of naïve (N) and T. muris-infected AKR mice that received either PBS or rIL-13. (D) Quantification of T. muris worm burden in AKR mice that received either PBS or rIL-13 (16 days after infection). Results are expressed as mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments containing three to four mice in each treatment group.

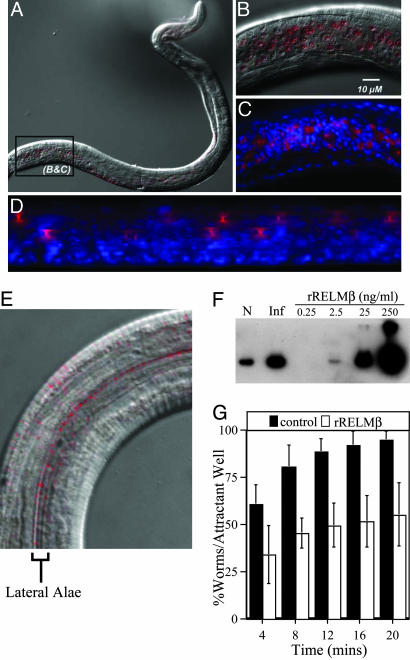

Given the temporal association among Th2 cytokine production, RELMβ expression, and worm expulsion, we hypothesized that RELMβ may contribute to worm expulsion by interacting directly with T. muris to impair essential biological functions of the parasite. To test this possibility, immunolocalization studies were performed to determine whether RELMβ associates with T. muris. Larval parasites were isolated from infected BALB/c mice at day 14 after infection, a time point that was coincident with the expression of RELMβ. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that RELMβ was associated with the bacillary band of larval T. muris (Fig. 4A). The bacillary band is composed of a longitudinal series of cuticular pores constituted by both epidermal gland cells and nonglandular cells (34, 35). Gland cells contain dendritic processes that run between the bacillary pores and adjacent bipolar nerve cells and are thought to play a critical role in chemosensory functions (36, 37). Immunofluorescent staining identified highly specific localization of RELMβ with the bacillary pores (Fig. 4B). Counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole confirmed that the localization of RELMβ was in pore-like structures and was not associated with nuclear staining (Fig. 4C). In addition, the generation of Z-stacked optical sections, which provides a 2D representation of 3D space, demonstrated that RELMβ staining was localized in funnel-shaped structures (Fig. 4D) with a diameter of ≈1–2 μm at its narrowest point (Fig. 4B), which is consistent with previous descriptions of the bacillary pores (34, 38). Control blocking experiments confirmed the high specificity of this staining pattern (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 4.

RELMβ binds specifically to structures located on the integument of parasitic nematodes and inhibits the chemotaxis of S. stercoralis in vitro. (A) Cy3 (red) immunofluorescent detection of RELMβ binding to the integument of T. muris isolated from BALB/c mice at 14 days after infection. The differential interference contrast is a ×20 magnification. (B) High-power magnification of A (×100). (C) Cy3 (red) immunofluorescence for RELMβ with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole nuclear counterstain (blue). Image is ×100 magnification. (D) Fluorescent Z-stacked optical images of T. muris stained for RELMβ (red) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) rotated 80°. Image is ×100 magnification. (E) Cy3 (red) immunofluorescent detection of RELMβ binding to paired lateral alae on the cuticle of S. stercoralis. The differential interference contrast is a ×120 magnification. (F) Immunoblot for RELMβ in protein isolated from the stool of a naïve (N) and T. muris-infected (Inf) BALB/c mice (16 days after infection), and various concentrations of rRELMβ. (G) In vitro chemotaxis assay of S. stercoralis L3i preincubated with either rIL-4 (50 ng/ml, control) or rRELMβ (50 ng/ml) for 30 min. Percentage of worms reaching the attractant well was determined at the indicated times. Results are expressed as mean percentage ± SD of three independent experiments.

The association of host RELMβ with chemosensory components of the bacillary band suggested that RELMβ might impair sensory functions of GI nematodes. This hypothesis was tested by exposing the GI nematode parasite S. stercoralis, whose rapid migration toward host-derived chemoattractants is readily measured ex vivo, to a concentration of rRELMβ similar to that in the stool of T. muris-infected BALB/c mice (Fig. 4F). Whole-mount staining of S. stercoralis incubated with rRELMβ showed that this protein binds to specific pore-like structures along the outer edge of lateral alae on the nematode cuticle (Fig. 4E). The alae of S. stercoralis overlie lateral cords that are rich in neuronal tissue (39) and may be functionally analogous to the bacillary band, which is a modification of the lateral cord in Trichurids (37). Studies have shown that active, host-finding L3i stages of this parasite rapidly migrate toward canine skin extract but fail to undergo migration in the absence of stimuli (40). Remarkably, rRELMβ impaired the chemoattraction of S. stercoralis dramatically (Fig. 4G). By contrast, neither the random (not attractant-directed) movements nor the viability of the parasites were affected by exposure to rRELMβ (data not shown). Thus, RELMβ can directly impair nematode chemosensory function in vitro and provides a demonstration for a biological function for this protein.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the induction of RELMβ is a highly specific Th2 cytokine-dependent intestinal response that is elicited after exposure to phylogenetically and biologically distinct GI nematode parasites that inhabit different regions of the GI tract. Furthermore, maximal RELMβ expression is coincident with the production of Th2 cytokines, the histologic appearance of goblet-cell hyperplasia, and host protective immunity. The localization of RELMβ to a nematode chemosensory apparatus, as well as its ability to inhibit nematode chemotaxis in vitro, suggests that RELMβ functions as a critical immune-effector molecule in the expulsion of GI nematodes by disrupting the ability of nematodes to optimally sense the GI microenvironment. Although these findings will require confirmation in vivo by examination of a host in which the RELMβ gene has been disrupted, our results are consistent with the observation that a related gene product, RELMα, binds to neurons and alters their function in vertebrate systems (17). Therefore, coupled with other intestinal responses associated with expulsion of helminths, including mast-cell degranulation and smooth-muscle contractility (41–43), our data suggest that expression of RELMβ may be a critical component in the arsenal of type 2-regulated effector mechanisms that precipitate worm expulsion and host protective immunity.

The conservation of the RELMβ gene in vertebrates and its absence from the genomes of lower organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans (18) suggests that RELMβ may have arisen during evolution as a host-defense mechanism under selective pressure exerted by GI nematode parasites. Given the growing impact of resistance to existing anthelminthic drugs in the livestock industry (44), coupled with the potential for resistance to develop in human populations (45), the identification of RELMβ as a possible immune-effector molecule against GI nematodes may lead to novel immunotherapeutic approaches in the prevention or treatment of these infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI39368 (to G.D.W.), AI35914 (to P.S.), AI22662 (to G.A.S.), DK49780 (to M.A.L.), and DK07066 (to M.L.W.); Wellcome Trust Grants 059967 (to D.A.) and 060312 (to P.A.K.); and Molecular Biology Core, Morphology Core, and Pilot Feasibility Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Center Grant DK50306 (to D.A.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; Th2, T helper type 2; rIL-n, recombinant IL-n; L3i, infective third-stage larvae.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. (2001) 54th World Health Assembly: Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections (item 13.3, World Health Organization, Geneva).

- 2.Claerebout, E. & Vercruysse, J. (2000) Parasitology 120 S25–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton, S. E. & Meeusen, E. N. (2003) Parasite Immunol. (Oxf.) 25, 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maizels, R. M., Bundy, D. A., Selkirk, M. E., Smith, D. F. & Anderson, R. M. (1993) Nature 365, 797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller, H. R. (1996) Int. J. Parasitol. 26, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelman, F. D., Shea-Donohue, T., Goldhill, J., Sullivan, C. A., Morris, S. C., Madden, K. B., Gause, W. C. & Urban, J. F., Jr. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 505–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artis, D. & Grencis, R. K. (2001) in Parasitic Nematodes: Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Immunology, eds. Kennedy, M. W. & Harnett, W. (CABI, New York), pp. 331–371.

- 8.Maizels, R. M. & Yazdanbakhsh, M. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Else, K. J. & Grencis, R. K. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64, 2950–2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grencis, R. K. (1997) Chem. Immunol. 66, 41–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betts, C. J. & Else, K. J. (1999) Parasite Immunol. (Oxf.) 21, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller, H. R. & Huntley, J. F. (1982) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 144, 243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Specian, R. D. & Oliver, M. G. (1991) Am. J. Physiol. 260, C183–C193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenzie, G. J., Bancroft, A., Grencis, R. K. & McKenzie, A. N. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theodoropoulos, G., Hicks, S. J., Corfield, A. P., Miller, B. G. & Carrington, S. D. (2001) Trends Parasitol. 17, 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He, W., Wang, M. L., Jiang, H. Q., Steppan, C. M., Shin, M. E., Thurnheer, M. C., Cebra, J. J., Lazar, M. A. & Wu, G. D. (2003) Gastroenterology 125, 1388–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holcomb, I. N., Kabakoff, R. C., Chan, B., Baker, T. W., Gurney, A., Henzel, W., Nelson, C., Lowman, H. B., Wright, B. D., Skelton, N. J., et al. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 4046–4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steppan, C. M., Brown, E. J., Wright, C. M., Bhat, S., Banerjee, R. R., Dai, C. Y., Enders, G. H., Silberg, D. G., Wen, X., Wu, G. D. & Lazar, M. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loke, P., Nair, M. G., Parkinson, J., Guiliano, D., Blaxter, M. & Allen, J. E. (2002) BMC Immunol. 3, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stutz, A. M., Pickart, L. A., Trifilieff, A., Baumruker, T., Prieschl-Strassmayr, E. & Woisetschlager, M. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 1789–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerstmayer, B., Kusters, D., Gebel, S., Muller, T., Van Miert, E., Hofmann, K. & Bosio, A. (2003) Genomics 81, 588–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steppan, C. M. & Lazar, M. A. (2004) J. Intern. Med. 255, 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight, P. A., Wright, S. H., Lawrence, C. E., Paterson, Y. Y. & Miller, H. R. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1849–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight, P. A., Wright, S. H., Brown, J. K., Huang, X., Sheppard, D. & Miller, H. R. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 161, 771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artis, D., Shapira, S., Mason, N., Speirs, K. M., Goldschmidt, M., Caamano, J., Liou, H. C., Hunter, C. A. & Scott, P. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 4481–4487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward, S. (1973) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70, 817–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granzer, M. & Haas, W. (1991) Int. J. Parasitol. 21, 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomita, M., Kobayashi, T., Itoh, H., Onitsuka, T. & Nawa, Y. (2000) Respiration 67, 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liesenfeld, O. (1999) Immunobiology 201, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwakiri, D. & Podolsky, D. K. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. 280, G1114–G1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wynn, T. A. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bancroft, A. J., Artis, D., Donaldson, D. D., Sypek, J. P. & Grencis, R. K. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2083–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artis, D., Humphreys, N. E., Bancroft, A. J., Rothwell, N. J., Potten, C. S. & Grencis, R. K. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheffield, H. G. (1963) J. Parasitol. 49, 998–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkins, T. (1970) Parasitology 61, 357–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright, K. A. & Chan, J. (1973) Tissue Cell 5, 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbons, L. M. (2002) in The Biology of Nematodes, ed. Lee, D. L. (Taylor & Francis, New York).

- 38.Jenkins, T. (1969) Z. Parasitenkd. 32, 374–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schad, G. A. (1989) in Strongyloidiasis: A Major Roundworm Infection of Man, ed. Grove, D. I. (Taylor & Francis, New York).

- 40.Ashton, F. T., Li, J. & Schad, G. A. (1999) Vet. Parasitol. 84, 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madden, K. B., Whitman, L., Sullivan, C., Gause, W. C., Urban, J. F., Jr., Katona, I. M., Finkelman, F. D. & Shea-Donohue, T. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 4417–4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDermott, J. R., Bartram, R. E., Knight, P. A., Miller, H. R., Garrod, D. R. & Grencis, R. K. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7761–7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, A., McDermott, J., Urban, J. F., Jr., Gause, W., Madden, K. B., Yeung, K. A., Morris, S. C., Finkelman, F. D. & Shea-Donohue, T. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waller, P. J. (2003) Anim. Health Res. Rev. 4, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albonico, M., Crompton, D. W. & Savioli, L. (1999) Adv. Parasitol. 42, 277–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knight, P. A., Pemberton, D., Robertson, K. A., Roy, D. J., Wright, S. H. & Miller, H. R. P. (2004) Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.