Abstract

We identified the previously unknown structures of ribosylated imidazoleacetic acids in rat, bovine, and human tissues to be imidazole-4-acetic acid-ribotide (IAA-RP) and its metabolite, imidazole-4-acetic acid-riboside. We also found that IAA-RP has physicochemical properties similar to those of an unidentified substance(s) extracted from mammalian tissues that interacts with imidazol(in)e receptors (I-Rs). [“Imidazoline,” by consensus (International Union of Pharmacology), includes imidazole, imidazoline, and related compounds. We demonstrate that the imidazole IAA-RP acts at I-Rs, and because few (if any) imidazolines exist in vivo, we have adopted the term “imidazol(in)e-Rs.”] The latter regulate multiple functions in the CNS and periphery. We now show that IAA-RP (i) is present in brain and tissue extracts that exhibit I-R activity; (ii) is present in neurons of brainstem areas, including the rostroventrolateral medulla, a region where drugs active at I-Rs are known to modulate blood pressure; (iii) is present within synaptosome-enriched fractions of brain where its release is Ca2+-dependent, consistent with transmitter function; (iv) produces I-R-linked effects in vitro (e.g., arachidonic acid and insulin release) that are blocked by relevant antagonists; and (v) produces hypertension when microinjected into the rostroventrolateral medulla. Our data also suggest that IAA-RP may interact with a novel imidazol(in)e-like receptor at this site. We propose that IAA-RP is a neuroregulator acting via I-Rs.

Keywords: clonidine-displacing substance (CDS), hypertension, pancreatic beta cells, anti-IAA-RP antibodies, histamine

Imidazole-4-acetic acid (IAA) is a γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor agonist and a low-efficacy, partial agonist at γ-aminobutyric acid type C receptors (1), and in the CNS it mediates such effects as analgesia, sedation, hypnosis, aggression, and hypotension (1–4). Originally, IAA was thought not to exist in the brain but, using GC/MS, we showed (5, 6) its presence in perfused rat brain and cerebrospinal fluid. IAA can derive from transamination of histidine or oxidation of histamine (7–9). The former is likely to be the main pathway in the CNS, because there, histamine is mainly methylated. In addition, regional CNS levels of IAA (G.D.P., unpublished data) correlated with those of histidine transaminase (also termed kynurenine aminotransferase) (10) but not with those of histamine or its synthetic enzyme, and inhibition of histamine synthesis did not markedly affect IAA levels (11–13). Pulse–chase studies showed IAA could be conjugated with phosphoribosyl-pyrophosphate (while hydrolyzing ATP) to produce an IAA-ribotide (14–17). The latter can be dephosphorylated by phosphatases and 5′ nucleotidases (11, 15) to produce an IAA-riboside (7, 8, 11, 15, 18). Robinson and Green (19) were the first to show traces of IAA-ribotide and IAA-riboside in brains of rats given [14C]histidine (i.p.). However, because brains were not perfused, this finding could have been attributed to circulating conjugates produced by ribosylation in the periphery. Evidence for IAA ribosylation in the CNS came from our studies (11) showing both conjugates in rats given [3H]histamine intracerebroventricularly. These results suggested the existence of endogenous mechanisms for IAA ribosylation in the CNS and were consistent with the observation that levels of IAA conjugates are >50-fold higher (G.D.P., unpublished data) than those of free IAA (100–200 pmol/g) in perfused rat brains (5). The presence of micromolal levels of ribosylated IAA in brain, the requirement for ATP to produce IAA-ribotide (14, 15, 17), and its rapid turnover (11, 15) led us to hypothesize that IAA-ribotide has a significant physiological role.

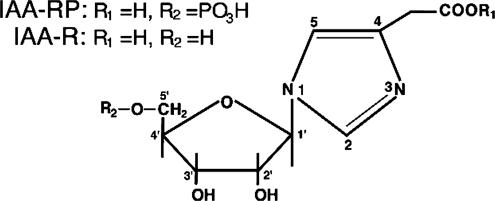

To investigate this, we synthesized the two C(1′)-N isomers of IAA-ribotide, imidazole-4-acetic acid (I-4-AA-RP) and imidazole-5-acetic acid-ribotide (I-5-AA-RP) (Fig. 1), to establish the precise structures of the endogenous conjugates, which had never been determined (7, 14–20). We then pursued the hypothesis that endogenous IAA-ribotide may interact with “imidazoline-Rs” (I-Rs), formerly the “imidazole-Rs” postulated by Karppanen and coworkers (4, 22, 23). [The concept of I-Rs arose from the fact that some effects of imidazoline-like α-adrenergic receptor (α-R) ligands (e.g., clonidine) are blocked by imidazoles and imidazolines and are incompletely mimicked or blocked by drugs lacking similar structures, such as the catecholamines (4, 24–26).] Three I-R subclasses are known. I1Rs and I3Rs regulate processes, such as sympathetic outflow and blood pressure by the rostroventrolateral medulla (RVLM), and the release of arachidonic acid (AA) from PC12 cells and of insulin from pancreatic islets (25–29). I1Rs have been characterized pharmacologically and a candidate cDNA has been cloned (30), whereas I3Rs are associated with the exocytotic pathway in pancreatic beta cells, which may include  channels (26, 28, 29, 31, 32). I2Rs are binding sites on monoamine oxidases and possibly other proteins (33). The initial suggestion that IAA-ribotide may be an I-R ligand came from our observation that it had physicochemical propertiesm similar to those of an unidentified endogenous substance(s) reported to act at I1Rs and I3Rs (25, 26, 34–38). This substance(s), extracted from mammalian tissue, was proposed as a putative I-R ligand and called clonidine-displacing substance (CDS), on the basis of its ability to displace the imidazoline drug clonidine (or its congeners) from I-R-specific sites. Some CDSs may contain a group of substances rather than a single entity, but, thus far, only one, agmatine, has been identified in one preparation (25, 26). However, agmatine binds mainly to I2 sites (where its role is unknown), has actions unrelated to I-Rs (39), and lacks significant activity at I1Rs and I3Rs (25, 26). Here, we demonstrate that I-4-AA-RP is the endogenous ribotide isomer (Fig. 1) and we show that I-4-AA-RP is an agonist for I1Rs and I3Rs.

channels (26, 28, 29, 31, 32). I2Rs are binding sites on monoamine oxidases and possibly other proteins (33). The initial suggestion that IAA-ribotide may be an I-R ligand came from our observation that it had physicochemical propertiesm similar to those of an unidentified endogenous substance(s) reported to act at I1Rs and I3Rs (25, 26, 34–38). This substance(s), extracted from mammalian tissue, was proposed as a putative I-R ligand and called clonidine-displacing substance (CDS), on the basis of its ability to displace the imidazoline drug clonidine (or its congeners) from I-R-specific sites. Some CDSs may contain a group of substances rather than a single entity, but, thus far, only one, agmatine, has been identified in one preparation (25, 26). However, agmatine binds mainly to I2 sites (where its role is unknown), has actions unrelated to I-Rs (39), and lacks significant activity at I1Rs and I3Rs (25, 26). Here, we demonstrate that I-4-AA-RP is the endogenous ribotide isomer (Fig. 1) and we show that I-4-AA-RP is an agonist for I1Rs and I3Rs.

Fig. 1.

Imidazole-4-acetic acid-ribotide [IAA-RP; 1-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)imidazole-4-acetic acid 5′-phosphate] and its metabolite, IAA-R [1-(β-d-ribofuranosyl)imidazole-4-acetic acid] present in vivo. Their corresponding nonphysiological isomers (depicted in refs. 16, 20, and 21) are I-5-AA-RP and I-5-AA-R, in which C(1′) is linked to the N closest to the acetate side chain.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Synthesis. We synthesized I-4-AA-RP-Na2 and I-4-AA-R HCl (Fig. 1) by modification of the method described for I-5-AA-RP and I-5-AA-R (21). Before that report, structures of even synthetic IAA conjugates were unknown (40, 41).

Animal and Tissue Sources. Animal Care and Use Committees of the authors' institutions approved all animal experiments. Human pancreata were harvested from heart-beating cadaver organ donors with next of kin's consent. Sprague–Dawley rats were used in most studies. Spontaneously hypertensive (SH) rats were used in blood pressure and IAA-RP release studies. Animals were obtained commercially.

Identification of IAA-Ribotide by HPLC. Bovine brain CDS (42), human cerebrospinal fluid, and rat brain extracts (12, 13) were eluted from Dowex-AG-acetate columns (1–3 N acetic acid) and analyzed by HPLC (43). Authentic IAA-ribotides (Fig. 1) and biological samples, equilibrated with 10 mM H3PO4 (pH 2.85), were eluted with a 2.5–62% KH2PO4 buffer (750 mM, pH 4.4) gradient. Other endogenous imidazoles, nucleotides, and nucleosides (e.g., IAA, IAA-R, AMP, and ATP) have retention times different from IAA-ribotides or negligible absorbance at 220 nm. A220 of both isomers correlated with quantity (0.02–20 μg; r = 0.96, P < 0.01); their elution times differed by ≈3 min.

Alkaline Phosphatase (Alk-Pase) Hydrolysis of CDS. Because [3H]IAA-ribotide produced in vivo was cleaved by alk-Pase (11), we examined whether CDS contains a ribose-P. Samples containing 26.2 units of CDS (42) were incubated (4 h in 250 μl) with 20 units of alk-Pase (Sigma) in activation buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl/5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.7, 37°C), thermally inactivating (4°C) medium, or alk-Pase inactivation buffer (5 mM EDTA). Samples were then assayed for CDS-binding activity (42). (One unit = amount of CDS that inhibits 50% of I1R-specific [3H]clonidine binding to bovine adrenal membranes. In this case, CDS displayed its IC50 after a 26.2-fold dilution.)

Affinity-Purified Anti-IAA-RP Abs. Anti-IAA-RP sera were raised in rabbits immunized with I-4-AA-RP linked to keyhole limpet hemocyanin by using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (Sigma). Cross-reactivities were eliminated by successive solid-phase adsorptions of serum with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide-modified BSA, AMP-BSA, ATP-BSA, and rat serum proteins. Purified Abs were obtained by affinity chromatography with I-4-AA-RP bound to agarose.

Quantitative ELISA. Rat brain homogenates were boiled, cooled, and centrifuged. Supernatants, extracted with butanol/chloroform (5, 6, 12, 13), were mixed with an equal volume of anti-IAA-RP Abs (3% BSA, 20 mM PBS). After incubation (37°C, 1 h), four 100-μl samples were incubated (16 h, 4°C) in plates coated with I-4-AA-RP-BSA. Wells were washed, reacted (37°C, 1 h) with peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit Abs (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories), washed again, then developed with ABTS or TMB substrates (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). I-4-AA-RP levels were estimated from standard inhibition curves (1 pmol–10 nmol). Controls included samples devoid of I-4-AA-RP, anti-I-4-AA-RP sera, or secondary Ab. To study IAA-RP released from P2 preparations (0.08–20 pmol), protein-free supernatants (in 10% trichloroacetic acid) and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit Abs and peroxidase-streptavidin were used.

Immunocytochemistry. Anesthetized rats were perfused transcardially with 100 ml of PBS (room temperature), 100 ml of 4% 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide in PBS (room temperature), then 300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (4°C). Brains were postfixed (2 h, 4% paraformaldehyde). Vibratome sections (50 μm) were pretreated with 0.3% H2O2, rinsed with PBS, blocked in 5% normal goat serum (1 h), and then incubated with affinity-purified anti-IAA-RP Abs. Control sections received preimmune serum, Abs preabsorbed with I-4-AA-RP, or no primary Abs. After 16 h at 4°C, sections were washed and stained (Vectastain Elite, Vector Laboratories) by using diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/ml, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0/0.01% H2O2), osmicated (0.1% OsO4, 30 sec), rinsed, and mounted.

Competition Binding Assays. Bovine adrenal medulla or RVLM membranes were suspended in Tris buffer (5 mM, pH 7.7, with EDTA, EGTA, and MgCl2, all 500 μM) (0.2–1 mg of protein per ml) and labeled with 0.5 nM [3H]clonidine or 1 nM p-[125I]iodoclonidine, respectively (44). Because the RVLM contains I-Rs and α2-receptors (α2Rs), an imidazoline/adrenergic agent, BDF-6143 (10 μM) (45), was used to assess total binding. Specific binding to α2Rs or I-Rs was defined by inhibition with (–)epinephrine (100 μM) or cimetidine (10 μM), respectively. The latter was also used with adrenal membranes. Ascorbic acid (1 mg%) was used in studies with catecholamines. Incubations were stopped by vacuum filtration over prewashed (Tris·HCl) glass filters. Captured 3H and 125I were then measured by liquid scintillation. Results were analyzed by using nonlinear regression (prism, GraphPad, San Diego). KI values were assessed by using a two-component logistic equation.

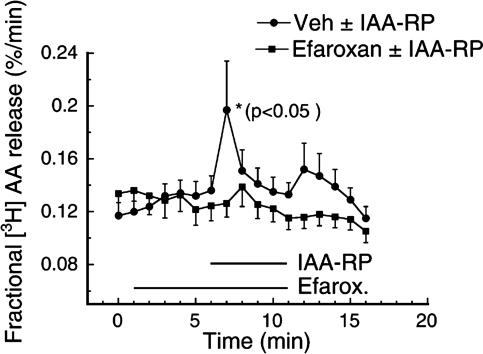

I1R Model: [3H]Arachidonic Acid (AA) Release from PC12 Cells. Assays (27) were done after a 30-min washout to attain a stable background. Cells were superfused with 0.01% BSA in Krebs buffer (KrB) for seven 1-min fractions (baseline), then treated with 10 μM or 100 μM I-4-AA-RP alone, or together with efaroxan (10 μM), a prototypical I1 antagonist/I3 agonist. Controls included baseline release with vehicle alone (0–7 min) or vehicle containing efaroxan (5min) before adding I-4-AA-RP. 3H-labeled products (>98% AA) collected in each 1-min fraction were expressed as fractional release defined as the % total radioactivity incorporated into cells, corrected for [3H]AA previously released (27).

I3R Model: Insulin Release from Pancreas (26, 28, 29). Islets of Langerhans from male Wistar rats and human pancreata were isolated by collagenase digestion. Hand-picked islets were incubated in NaHCO3-buffered saline containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mg/ml BSA, and test reagents. After incubation, insulin levels in supernatants were analyzed by radioimmunoassay. The I3 blocker, KU-14R, served to verify I3R function.

Ca2+-Dependent IAA-Ribotide Release. Synaptosome and vesicle-enriched P2 fractions (46), each pooled from two SH rat brains (47), were suspended in Krebs buffer (KrB) saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, divided into 0.5-ml aliquots, and mixed with 0.5 ml of either (i) KrB or (ii) KrB without Ca2+ containing 55 mM K+ (to depolarize cells) and EDTA (to chelate endogenous Ca2+) or (iii) KrB with 55 mM K+ (release buffer). I-4-AA-RP was measured (ELISA) after incubation (10 min, 37°C). Release was expressed as percent of controls: [IAA-RP in release media/mean of the two nonrelease controls in each experiment (n = 5)] × 100. Results were analyzed by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for values that exceeded controls and by Wilcoxon's test.

Effects of Ribotide on Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and Heart Rate (HR). Bilateral I-4-AA-RP microinjections (60 nl, 100 nmol) into the RVLM of SH rats were performed (48) after the sympathoexcitatory area was confirmed by showing glutamate-induced MAP elevation of ≥30 mmHg (1 mmHg = 133 Pa). MAP and HR values were measured every 5 min. After each experiment, the injection site was marked by infusion of rhodamine microspheres. Changes were assessed relative to baseline values by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Dunnett's test. A second group of SH rats (injection controls) received vehicle injections to control for injection effects and for volume artifacts due to multiple injections. Vehicle contained 2 nmol of rilmenidine, a subthreshold dose, far below that known to cause any detectable effect (49). In a follow-up study, SH rats (n = 6) were given I-4-AA-RP then moxonidine. When used alone, the latter reduced MAP to normotensive levels (50).

Results

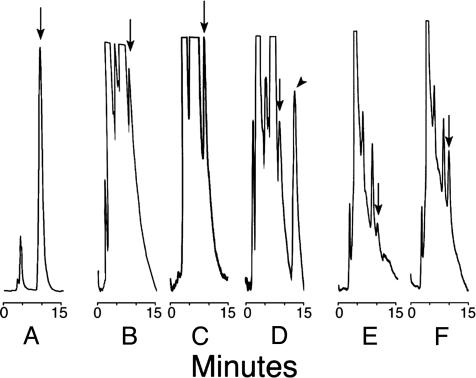

I-4-AA-RP Is the Endogenous Isomer. HPLC analysis showed that addition of either I-4-AA-RP or I-5-AA-RP to test samples produced nearly quantitative A220 peak-area recoveries. All biological samples (Fig. 2) displayed peaks indicative of I-4-AA-RP. A220 of the latter increased in samples mixed with synthetic I-4-AA-RP (50–200 ng, e.g., Fig. 2 C and F), whereas a novel peak appeared in samples mixed with I-5-AA-RP (Fig. 2D). These observations demonstrate that the I-4-AA-RP isomer (Fig. 1, hereafter denoted as “IAA-RP”) is present in tissues (Fig. 2) and in cerebrospinal fluid (data not shown). Its endogenous metabolite is therefore I-4-AA-R, hereafter denoted “IAA-R.” [IAA-R has also been found in samples from rats and humans by using GC/MS (unpublished data).]

Fig. 2.

Representative HPLC chromatograms showing A220nm (ordinate) after sample injections. Arrows indicate peaks corresponding to I-4-AA-RP; the arrowhead indicates the I-5-AA-RP isomer. (A) Authentic I-4-AA-RP (5 μg). (B) Rat brain extract alone. (C) Parallel sample of B mixed with authentic I-4-AA-RP (183 ng). (D) Parallel sample of B mixed with authentic I-5-AA-RP (200 ng). (E) Sample of bovine brain extract containing CDS activity. (F) Parallel sample of E mixed with authentic I-4-AA-RP (100 ng). Signal attenuation for E and F was 0.25 times that of B–D. Hereafter, the I-4-AA-RP isomer will be denoted “IAA-RP.” I-4-AA-R will be denoted “IAA-R.”

Specificity of Anti-IAA-RP Abs and Quantitative ELISA. Purified anti-IAA-RP Abs showed negligible cross-reactivity with >50 compounds (10 nM–0.1 mM), including free and BSA-conjugated imidazoles, such as IAA-R, I-5-AA-RP, I-5-AA-R, and IAA; related endogenous and synthetic pyrimidine- and purineribose-Ps (e.g., ZMP, AMP, ADP, ATP, cAMP, and cGMP); and unconjugated compounds, such as histidine and histamine, and their metabolites. Others included phosphatase and 5′ nucleotidase inhibitors and compounds relevant to the imidazol(in)e field, e.g., clonidine, cimetidine, efaroxan, KU-14R, agmatine, and idazoxan. Abs did not stain Western blots of rat brain homogenates.

Quantitative ELISA confirmed that rat brain extracts contained IAA-RP (1.1 ± 0.6 μg/g tissue, n = 8).

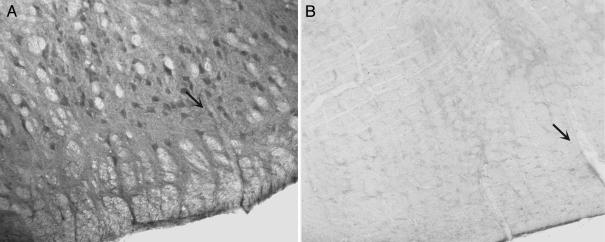

IAA-RP Is Present in Brainstem Neurons. RVLM neurons stained intensely in sections reacted with anti-IAA-RP Abs (Fig. 3A). Neuropil staining due to the presence of IAA-RP in neuronal processes was also intense. Myelinated axon bundles were unstained (Fig. 3). Adjacent sections treated with primary Abs preabsorbed with IAA-RP (Fig. 3B), preimmune serum, or with secondary Abs (horse anti-rabbit) alone showed no appreciable immunoreactivity. Neuronal staining was present in other brainstem areas, e.g., the solitary, gracile, vestibular, ventral cochlear, medial parabrachial and inferior olivary nuclei, and Purkinje cell somata and dendrites of the cerebellar cortex.

Fig. 3.

IAA-RP immunostaining in the rat RVLM. (A) Anti-IAA-RP-labeled neurons in the RVLM and other nuclei, showing cell bodies, and the neuropil, showing IAA-RP in dendritic processes. (B) The adjacent section, processed identically, but reacted with anti-IAA-RP Abs preincubated with IAA-RP (300 μM), showed no immunoreactivity. A blood vessel present in both sections is indicated with a black arrow.

Alk-Pase Depleted CDS Activity. Treatment with active alk-Pase decreased CDS activity from 26.2 to 6.7 units (–74%); inactivated enzyme had no effect. Therefore, a substance containing a hydrolyzable P-monoester appeared to mediate most of the CDS activity (42) consistent with conversion of IAA-RP to IAA-R.

IAA-RP Binds to Adrenal Medulla I1R Sites and Is an I1R Agonist in PC12 Cells. The adrenal medulla does not express α2-sites and is a model for I1R binding (27, 44). In this tissue, IAA-RP and IAA-R displaced [3H]clonidine with affinities (KI values) of 13 ± 2 μM and 24 ± 5 μM, respectively. [3H]AA release was studied in PC12 cells, which derive from an adrenal medullary tumor, and, like the adrenal medulla, express I1Rs but not α2Rs and are a model for I1R responses (27). IAA-RP caused a dose-related stimulation of [3H]AA release. IAA-RP at 10 μM increased release by 68 ± 29% (Fig. 4; P < 0.05; n = 13); 100 μM elicited a larger response (177 ± 89%; P < 0.05, n = 6; data not shown). In contrast, IAA-R (10 μM to 1 mM) showed no significant response. The I1 antagonist/I3 agonist efaroxan abolished responses to IAA-RP (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

IAA-RP stimulated [3H]AA release from PC12 cells. Superfusion of 10μM IAA-RP immediately increased [3H]AA release (•, X̄ ± SEM) with respect to baseline values [i.e., vehicle (Veh) alone, averaged over the first 5 min] (P < 0.05, Newman–Keuls; n = 11). Superfusion with the I1 antagonist/I3 agonist efaroxan (10 μM) (▪, n = 11) 5 min before and throughout IAA-RP superfusion blocked IAA-RP-induced release. Before IAA-RP was added, vehicle alone or vehicle containing efaroxan exhibited stable baselines, indicating that release was due to IAA-RP's I1R agonist activity.

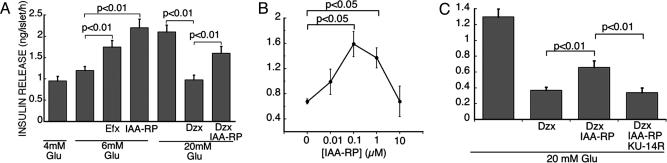

IAA-RP Is an I3R Agonist. Potentiation of glucose-induced insulin release is the best-characterized I3R-mediated response (26, 28, 29). As reported for CDS and other I3R agonists (28, 29, 51), IAA-RP increased insulin secretion from islets (Fig. 5). It also overcame inhibitory effects of the  agonist, diazoxide (Fig. 5). These IAA-RP effects are characteristic of I3R agonists, but, significantly, IAA-RP was far more potent than efaroxan (Fig. 5A), the prototypical I3 agonist/I1 antagonist. IAA-RP stimulation was biphasic in rat (Fig. 5B) and human islets. In rats, IAA-RP had an EC50 of 30–50 nM. Human islets appeared to be even more sensitive, displaying an EC50 of ≈3 nM. The I3R antagonist KU-14R (28) abolished IAA-RP-induced secretion (Fig. 5C), confirming I3R activity.

agonist, diazoxide (Fig. 5). These IAA-RP effects are characteristic of I3R agonists, but, significantly, IAA-RP was far more potent than efaroxan (Fig. 5A), the prototypical I3 agonist/I1 antagonist. IAA-RP stimulation was biphasic in rat (Fig. 5B) and human islets. In rats, IAA-RP had an EC50 of 30–50 nM. Human islets appeared to be even more sensitive, displaying an EC50 of ≈3 nM. The I3R antagonist KU-14R (28) abolished IAA-RP-induced secretion (Fig. 5C), confirming I3R activity.

Fig. 5.

IAA-RP stimulated insulin release from rat islets. (A) Release in the presence of glucose (Glu) alone (4, 6, and 20 mM) or combined with (i) efaroxan (Efx, 100 μM), (ii) IAA-RP (1 μM), (iii) diazoxide (Dzx, 200 μM), and (iv) IAA-RP (1 μM) and diazoxide (200 μM) together. Each bar represents (X̄ ± SEM, n = 8). Brackets denote differences (two-way ANOVA, repeated measures) between treatment groups. (B) Release from islets incubated with increasing concentrations of IAA-RP in the presence of Glu (20 mM) and diazoxide (200 μM) (n = 6). (C) Release from islets incubated in the presence of Glu with (i) diazoxide (200 μM), (ii) diazoxide (200 μM) and IAA-RP (1 μM), and (iii) diazoxide (200 μM), IAA-RP (1 μM), and the I3 blocker KU-14R (100 μM) (n = 8).

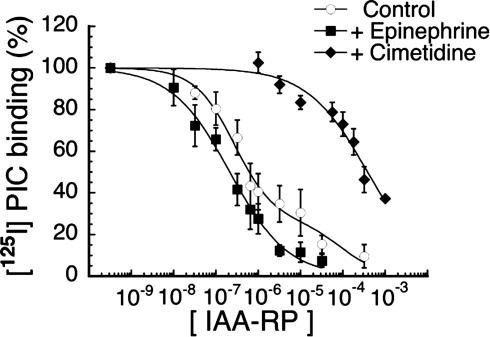

IAA-RP Has High Affinity for Brainstem I-R Sites. In the RVLM, p-[125I]iodoclonidine labels both I-R and α2-sites (44). Competition curves for IAA-RP (Fig. 6) were biphasic, consisting of both high- and low-affinity sites. In the absence of I-R and α2-masking ligands, the high-affinity component comprised 71 ± 5% (X̄ ± SEM) of total binding (KI, 160 ± 38 nM). The remaining sites showed >300-fold lower affinity for IAA-RP (KI, 57 ± 33 μM). After masking α2Rs with epinephrine, IAA-RP high-affinity binding accounted for 86 ± 4% of total binding (KI, 100 ± 19 nM); the KI of low-affinity sites was 60 ± 48 μM. Conversely, when I sites were masked with the imidazole cimetidine, IAA-RP high-affinity binding was abolished and only low-affinity sites remained (presumably α2-Rs; KI, 210 ± 32 μM). Thus, in the RVLM, IAA-RP exhibited high affinity for I-R sites and was >1,000-fold more selective for I-Rs than for presumed α2-sites. In parallel assays, IAA-R had very low affinity (KI, 266 ± 48 μM; not shown).

Fig. 6.

Specific binding of p-[125I]iodoclonidine (PIC) (1 nM) to membrane sites in bovine RVLM. Inhibition curves were produced with increasing concentrations of IAA-RP. Total nonspecific binding was defined by using BDF-6143. Curves show the absence of masking ligand (○, control), the presence of epinephrine (♦) to mask α2Rs, and the presence of cimetidine (♦) to mask I-Rs. Data show X̄ ± SEM of four to six experiments, each done in triplicate. Curves were normalized to total specific binding under each experimental condition and plotted by using nonlinear curve-fitting.

IAA-RP Shows Ca2+-Dependent Release from Neuronal Terminals.IAA-RP release from P2 nerve endings was studied. IAA-RP levels in controls showed little variation (≤11%) within each preparation but varied considerably among preparations (5.7–35.5 fmol/μl). Nevertheless, a significant net effect was observed (P < 0.05, ANOVA). Mean IAA-RP release in samples containing Ca2+ exceeded by 40.3% (P = 0.03, Wilcoxon's test) the mean (and the median by 49%) of controls grouped together (X̄ ± SEM: 22.7 ± 4.8 fmol/μl) (i.e., nondepolarized preparations or those deprived of Ca2+ by EDTA). These data demonstrate that IAA-RP is stored in fractions that contain synaptic endings and IAA-RP undergoes depolarization-induced release consistent with transsynaptic function.

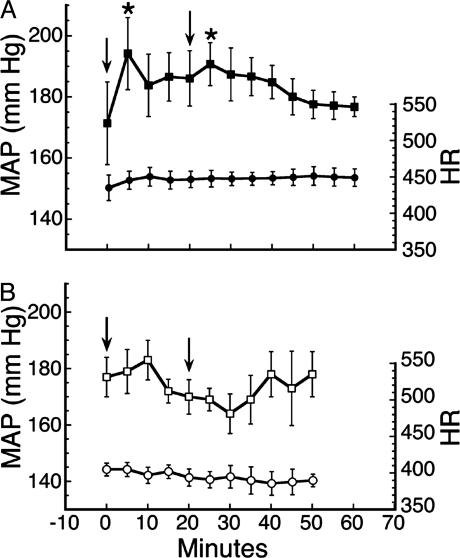

Microinjection of IAA-RP into the RVLM Produces Hypertension. SH rats were used as a model system (50), because IAA-RP, as an I1 agonist (Fig. 4), was expected to lower MAP. Yet, IAA-RP immediately raised MAP an average of ≈25 mmHg over baseline (Fig. 7A; P < 0.01, ANOVA; n = 6). A second microinjection 20 min later again raised MAP (Fig. 7A; P < 0.05). In contrast, HR showed no significant changes. IAA-R (100 nmol; n = 3; data not shown) did not alter MAP or HR significantly. Injection alone (injection controls) did not alter HR or MAP (Fig. 7B), confirming that MAP elevations were due to IAA-RP. In a smaller study using normotensive rats (n = 3), IAA-RP produced a similar hypertensive response. To assess whether IAA-RP's effect could be reversed, the I1 agonist moxonidine (MOX; 4 nmol) was microinjected into SH rats whose MAP had been elevated (20.4 ± 5.6% above baseline) after six 100-nmol doses of IAA-RP. MOX completely reversed IAA-RP's effect and lowered MAP (37.3 ± 6.3%) toward normotensive levels within 30 min. This finding further suggests that IAA-RP's hypertensive effect was not mediated by I1Rs.

Fig. 7.

Physiological effects of IAA-RP. (A) IAA-RP induced increases in MAP (▪), but not HR (•) after microinjections (arrows) of IAA-RP (100 nmol) into the RVLM of SH rats. Symbols denote X̄ ± SEM values. Increases in MAP (P < 0.01; ANOVA) were observed (*) at 5 and 25 min (each P < 0.05, Dunnett's test) when compared with rats' baseline values. (B) Other SH rats (n = 6) used as “injection controls” (□, MAP; ○, HR) were given vehicle (arrows) containing an inert substance (see Materials and Methods). Absence of injection-related actions implies that increases in MAP were due to IAA-RP.

Discussion

This report addresses the identification of the structure of the endogenous IAA-RP isomer, the ability of the latter to interact with I-Rs, and the physiological significance of such interactions. HPLC studies (Fig. 2) of tissue extracts revealed the biological isomer to be I-4-AA-RP (Fig. 1). Its presence in brainstem regions and, in particular, in the RVLM (Fig. 3) is significant, because this region is an important site of action for a class of antihypertensive agents that are thought to exert their effects by means of I1Rs (48–50). Several observations indicate that IAA-RP is an I-R agonist. First, IAA-RP bound to prototypical I1Rs in adrenal tissue and promoted AA release from PC12 cells (Fig. 4). Second, IAA-RP induced a robust stimulatory response in pancreatic islets (Fig. 5), consistent with I3R activity. In fact, IAA-RP was unusually potent (EC50, 30–50 nM; Fig. 5B) in comparison with efaroxan, the prototypical I3 agonist, which typically shows maximal stimulation at ≈100 μM (28, 31). Notably, similar responses were elicited by CDS (28, 51), a putative but unidentified endogenous I-R ligand. Because our CDS preparation contained IAA-RP (Fig. 2), and alk-Pase abolished most of CDS's activity, we surmise that CDS I-R activity might derive from IAA-RP. Historically, CDS was first shown to displace clonidine from α2Rs (25, 26, 34–38). Thus, if IAA-RP is the active factor in CDS, then it might also be expected to act at α2Rs. Although we have not studied this formally, IAA-RP's biphasic response (Fig. 5B) in islets provides physiological evidence consistent with the possibility that submicromolar levels of IAA-RP stimulate insulin release, but higher levels are inhibitory. Considering that IAA-RP affinity for I-Rs vastly exceeds that for (presumed) α2-sites (Fig. 6), the stimulatory phase can be explained by I-R activation whereas the inhibition may be due to α2R activation (29).

Some of our observations were unexpected because, as an I1 agonist (Fig. 4), IAA-RP injection into the RVLM was expected to lower blood pressure, as has been observed with other I1 agonists (48, 50). Instead, as observed with CDS in normotensive rats (35), IAA-RP produced a rapid, transient increase in MAP (Fig. 7A), despite approaching MAP ceiling effects in SH rats. These observations compelled us to reconsider the actions of I-Rs within the RVLM, where I-R activity has been attributed to I1 sites because its pharmacological profile was consistent with that of I1R models (27, 48). The most direct explanation for our results is that the RVLM contains two cimetidine-sensitive I-R subtypes, I1Rs and an undefined I-R subtype, which regulate blood pressure in a reciprocal manner. This contention is supported by the fact that the IAA-RP binding profile in the RVLM [which exhibits both high- and low-affinity sites (Fig. 6)] differs markedly from that of the single site observed in adrenal tissue, which contains prototypical I1R sites. Affinities of high-affinity sites were >100-fold greater than those of both low-affinity RVLM sites and adrenal I1R sites. Furthermore, when ratios of affinities of the IAA-RP and IAA-R pair were considered, the KI (IAA-RP, low-affinity)/KI (IAA-R) ratio in the RVLM was nearly the same as the KI (IAA-RP)/KI (IAA-R) ratio in adrenal tissue. Yet, both ratios were orders of magnitude different from the KI (IAA-RP, high-affinity)/KI (IAA-R) ratio in the RVLM. Taken together, our data suggest that in the RVLM the low-affinity site is I1R-like and that IAA-RP's hypertensive effect (Fig. 7) derives from a non-I1R, high-affinity site. Although the nature of this putative receptor is unknown, we note that the KI of the high-affinity site (100 nM; Fig. 6) appears to be congruent with its EC50 at I3Rs (30–50 nM; Fig. 5B), and that the I3 agonist efaroxan also induces hypertension when injected into the RVLM (27, 44). Because evidence exists that, in islets, I3 agonists interact with  channels (28, 29), that the latter are abundant in the RVLM (52), and that imidazol(in)e-induced closure of

channels (28, 29), that the latter are abundant in the RVLM (52), and that imidazol(in)e-induced closure of  channels promotes cellular excitability (51), we hypothesize that a site(s) related to these channels may mediate the effects of IAA-RP. Thus, the proposition that IAA-RP might act by means of midbrain I3-like-Rs merits further consideration.

channels promotes cellular excitability (51), we hypothesize that a site(s) related to these channels may mediate the effects of IAA-RP. Thus, the proposition that IAA-RP might act by means of midbrain I3-like-Rs merits further consideration.

Our data suggest that IAA-RP may participate in transsynaptic signaling in brain, because it exists in brainstem neurons (Fig. 3), exhibits depolarization-induced Ca2+-dependent release from P2 synaptosomal elements, has relatively high affinity for membrane-bound I-R sites (Fig. 6), and produces physiological effects on exogenous application (Fig. 7A). IAA-RP is rapidly metabolized by phosphatases and ecto-5′-nucleotidases (11, 15) (G.D.P., unpublished data), both membrane-bound, to produce IAA-R, which has far less activity than IAA-RP. This would be compatible with a mechanism for rapid removal of IAA-RP so as to regulate its synaptic levels. Collectively, these observations meet the major requirements (53) to suggest that IAA-RP is a neurotransmitter. Although more definitive assertions await further studies, to date we have found nothing inconsistent with this hypothesis. Thus, one can speculate how IAA-RP might tonically overstimulate brainstem I-Rs to produce hypertension. The potent stimulation of insulin release by IAA-RP, its ability to induce AA release, and IAA-R's presence in plasma and urine (7–9, 18) also suggest that IAA-RP might exert hormone-like activity in the periphery. Indeed, IAA-RP's actions in the RVLM and in the pancreas reported here suggest it could be a link connecting the disorders of hypertension and diabetes (24, 28, 29, 48).

We acknowledge that different preparations of CDS (25, 34–38, 42) may contain variable amounts of IAA-RP and/or other potentially active substances. [One possibility is harmane (54).] Nevertheless, our data provide evidence that IAA-RP has a hitherto unrecognized physiological and/or pathophysiological function in the CNS and periphery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Jack Peter Green for promoting early phases of this project, Drs. R. F. L. James and S. Swift (University of Leicester, Leicester, U.K.) for providing human islets and Dr. E. Kukielka for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS28012 (to G.D.P), National Aeronautics and Space Administration Award NAG2-1191 (to G.R.H.), the Wellcome Trust and Diabetes, UK (to N.G.M. and S.L.F.C.), and National Institutes of Health Grant HL44514 (to P.E.).

Abbreviations: IAA, imidazole-4-acetic acid; IAA-RP, IAA-ribotide; IAA-R, IAA-riboside; I-5-AA-RP, imidazole-5-acetic acid-ribotide; RVLM, rostroventrolateral medulla; CDS, clonidine-displacing substance; I-R, imidazol(in)e receptor; AA, arachidonic acid; α2R, α2-receptor; alk-Pase, alkaline phosphatase; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; SH, spontaneously hypertensive.

Footnotes

Both are small (<1,000 Da) molecules devoid of amino acids and free amino groups and show a UVMAX at 210 –220 nm. Both are soluble in water and methanol but not in organic solvents, are stable for hours in weak acids and bases, are thermostable at 100°C, and retain activities after lyophilizations. IAA-ribotides can act as zwitterions (the imidazole ring can be protonated or deprotonated), and, like clonidine-displacing substance (CDS), be retained on either cation or anion exchangers. The ribotides are negatively charged at physiological pH.

References

- 1.Tunnicliff, G. (1998) Gen. Pharmacol. 31, 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts, E. & Simonsen, D. G. (1966) Biochem. Pharmacol. 15, 1875–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus, R. J., Winters, W. D., Roberts, E. & Simonsen, D. G. (1971) Neuropharmacology 10, 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karppanen, H. (1981) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandelwal, J. K., Prell, G. D., Morrishow, A. M. & Green, J. P. (1989) J. Neurochem. 52, 1107–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prell, G. D. & Morrishow, A. M. (1989) J. Chromatogr. 472, 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabor, H. & Hayaishi, O. (1955) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77, 505–506. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schayer, R. W. (1959) Physiol. Rev. 39, 116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green, J. P., Prell, G. D., Khandelwal, J. K. & Blandina, P. (1987) Agents Actions 22, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuno, E., Schmidt, W., Parks, D. A., Nakamura, M. & Schwarcz, R. (1991) J. Neurochem. 57, 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas, B. & Prell, G. D. (1995) J. Neurochem. 65, 818–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prell, G. D., Douyon, E., Sawyer, W. F. & Morrishow, A. M. (1996) J. Neurochem. 66, 2153–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prell, G. D., Morrishow, A. M., Duoyon, E. & Lee, W. S. (1997) J. Neurochem. 68, 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes, J. F., Castellani, O. & Plese, M. (1960) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 3, 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowley, G. M. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 239, 2593–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowley, G. M. (1971) Methods Enzymol. 17B, 770–773. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss, J., de Mello, M. C., Vaughan, M. & Beaven, M. A. (1976) J. Clin. Invest. 58, 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karjala, S. A. (1955) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77, 504–505. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson, J. D. & Green, J. P. (1964) Nature 203, 1178–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder, S. H., Axelrod, J. & Bauer, H. (1964) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 144, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matulić-Adamić, J. & Watanabe, K. A. (1991) Kor. J. Med. Chem. 1, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paakkari, I., Karppanen, H. & Paakkari, P. (1979) Acta Med. Scand. 625, 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karppanen, H., Paakkari, I. & Paakkari, P. (1979) in Histamine Receptors, ed. Yellin, T. O. (Spectrum Publications, New York), pp. 255–269.

- 24.Bousquet, P., Feldman, J. & Schwartz, J. (1984) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 230, 232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regunathan, S. & Reis, D. J. (1996) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 36, 511–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eglen, R. M., Hudson, A. L., Kendall, D. A., Nutt, D. J., Morgan, N. G., Wilson, V. G. & Dillon, M. P. (1998) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernsberger, P. (1998) J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 72, 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan, S. L. F. (1998) Gen. Pharmacol. 31, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan, N. G. (1999) Exp. Opin. Invest. Drugs 8, 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piletz, J. E., Ivanov, T. R., Sharp, J. D., Ernsberger, P., Chang, C. H., Pickard, R. T., Gold, G., Roth, B., Zhu, H., Jones, J.C., et al. (2000) DNA Cell. Biol. 19, 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan, S. L. F. & Morgan, N. G. (1990) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 176, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan, S. L. F., Mourtada, M. & Morgan, N. G. (2001) Diabetes 50, 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remaury, A., Raddatz, R., Ordener, C., Savic, S., Shih, J. C., Chen, K., Seif, I., De Maeyer, E., Lanier, S. M. & Parini, A. (2000) Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 1085–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meeley, M. P., Ernsberger, P., Granata, A. R. & Reis, D. J. (1986) Life Sci. 38, 1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atlas, D. (1991) Biochem. Pharmacol. 41, 1541–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grigg, M., Musgrave, I. F. & Barrow, C. J. (1998) J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 72, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker, C. A., Hudson, A. L., Nutt, D. J., Dillon, M. P., Eglen, R. M., Chan, S. L. F., Morgan, N. G. & Crosby, J. (1999) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 378, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh, G., Hussain, J. F., MacKinnon, A., Brown, C. M., Kendall, D. A. & Wilson, V. G. (1995) Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 351, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu, M. Y., Piletz, J. E., Halaris, A. & Regunathan, S. (2003) Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 23, 865–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baddiley, J., Buchanan, J. G., Hayes, D. H. & Smith, P. A. (1958) J. Chem. Soc., 3743–3745.

- 41.Bauer, H. (1962) J. Org. Chem. 27, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piletz, J. E., Chikkala, D. N. & Ernsberger, P. (1995) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 272, 581–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter, A. J. & Muller, R. E. (1990) J. Chromatogr. 527, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ernsberger, P., Piletz, J. E., Graff, L. M. & Graves, M. E. (1995) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 763, 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Göthert, M., Moldering, G. J., Fink, K. & Schlicker, E. (1995) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 763, 405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whittaker, V. P., Michaelson, I. A. & Kirkland, R. J. A. (1964) Biochem. J. 90, 293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arneric, S. P., Giuliano, R., Ernsberger, P., Underwood, M. D. & Reis, D. J. (1990) Brain Res. 511, 98–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ernsberger, P. & Haxhiu, M. A. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 273, R1572–R1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez, R. E., Ernsberger, P., Feinland, G. & Reis, D. J. (1991) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 195, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ernsberger, P., Elliott, H. L., Weimann, H.-J., Raap, A., Haxhiu, M. A., Hofferber, E., Low-Kroger, A., Reid, J. L. & Mest, H. J. (1993) Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 11, 411–431. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan, S. L. F., Atlas, D., James, R. F. L. & Morgan, N. G. (1997) Br. J. Pharmacol. 120, 926–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Golanov, E. V. & Reis, D. J. (1999) Brain Res. 827, 210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erulkar, S. D. (1994) in Basic Neurochemistry, eds. Siegel, G. J., Agranoff, B. W., Albers, R. W. & Molinoff, P. B. (Raven, New York), pp. 181–208.

- 54.Musgrave, I. F. & Badoer, E. (2000) Br. J. Pharmacol. 129, 1057–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]