Abstract

It is usually assumed that pollen availability does not limit reproduction in wind-pollinated plants. Little evidence either supporting or contradicting this assumption exists, despite the importance of seed production to population persistence and growth. We investigated the role of pollen limitation in an invasive estuarine grass (Spartina alterniflora), with a manipulative pollen supplementation and exclusion experiment in areas of high population density and at the low-density leading edge of the invasion. We also quantified pollen deposition rates on stigmas and pollen traps along a windward to leeward gradient. We found pollen impoverishment at the low-density leading edge of a large invasion, causing an 8-fold reduction in seed set. We found 9-fold more pollen on stigmas of high-density plants than on those of low-density plants. Pollen deposition rates on stigmas and traps did not increase downwind of low-density plants but did increase downwind of high-density plants and dropped off precipitously across a gap that lacked pollen donors. The delay of appreciable numbers of seed caused by pollen limitation persists for decades until vegetative growth coalesces plants into continuous meadows, and this Allee effect has slowed the rate of spread of the invasion.

Grasses are among the most common, aggressive, and harmful invasive species (1). Almost all grasses are pollinated by wind. Many studies have demonstrated pollen limitation in animal-vectored plants (2, 3), but there is very little evidence on whether pollen availability limits reproduction in wind-pollinated plants. Wind-dispersed pollen has a leptokurtic dispersal distribution from point sources (4–7), and, therefore, the proportion of fertilized ovules and seed set in recipient plants decreases rapidly with distance from the pollen donor (8). Wind direction, speed, turbulence, and gravity also affect pollen deposition (9–11). The key to pollen availability is density of donor plants, again studied almost exclusively in animal-pollinated systems (12–18). The role of density in governing pollen limitation in wind-pollinated plants is only just beginning to be recognized (19–21) although some earlier work suggested its importance (22).

For nonindigenous plants, such investigations are crucial because pollen limitation can cause a depressed rate of seed production, and therefore of population growth, when individual density is low at the front of an invading population (23, 24). This is one mechanism causing an Allee effect (25, 26), a positive relationship between fitness and either numbers or density of conspecifics. A “strong” Allee effect results in negative per capita rate of growth when population density drops below a threshold. A “weak” Allee effect, as can be the case with long-lived adults, causes a depressed per capita rate of growth at low population density, but it never becomes negative (27, 28). A lack of mating opportunities among sparse or widely spaced individuals can result in an Allee effect and a slowing of the invasion (27–29).

In a large-scale, estuarine invasion of Spartina alterniflora (smooth cordgrass) in Willapa Bay, WA, colonists at the leading edge are isolated from one another (Fig. 1). Isolated colonists set <1/10th the seed of plants that have grown vegetatively and coalesced with their neighbors (30), and this has caused a weak Allee effect (29). S. alterniflora spreads within Willapa Bay by seed that floats on the tide, with virtually no recruitment by rhizome fragments (30). This tall, dense salt marsh grass has spread to cover ≈60 of the 230 square kilometers of intertidal lands since introduction from the Atlantic coast a century ago. This area occupied is far less than would be expected without the Allee effect (29).

Fig. 1.

Palix River study site. Shown is an aerial photograph of a low-density area on the left grading to dense meadow on the right. Locations of trap transects I–IV are represented by yellow lines. The image was prepared by J. C. Civille.

To test whether the distinct reduction in isolated plants' fecundity is due to insufficient availability of outcross pollen, we performed a manipulative experiment applying the treatments of pollen exclusion, pollen addition, and ambient control on closely adjacent isolated and meadow plants at the Palix River mudflats in Willapa Bay. This area was colonized about 1985, the plants began coalescing by 2000 (30) and continuous swards of S. alterniflora occupied most of the available substrate at the time of this experiment. To determine relative pollen loads between isolated and meadow plants, we collected stigmas from all experimental plants, as well as additional plants in the Palix River and two other areas within the bay. We set out pollen traps and collected adjacent stigmas across a gradient of plant density to measure the correlation between ambient pollen in the air and stigmatic pollen deposition rates and to assess the relative amounts of airborne pollen across a windward to leeward gradient.

Materials and Methods

Pollen Manipulations. Experimental manipulations occurred August 2003, beginning on August 11 (week 1) and August 25 (week 2), when daytime low tides coincided with early female phase flowering at the Palix River mudflats. On Monday and Tuesday of each week, we haphazardly chose equal numbers of isolated plants and meadow plants completely coalesced with their neighbors. We haphazardly assigned the treatments of pollen exclusion, pollen addition, and ambient unmanipulated control with 3, 5, and 5 inflorescences per plant respectively. On week 1, we applied all treatments to 8 plants and applied the pollen addition and ambient treatments to an additional 20 plants. On week 2, we applied all treatments to 16 plants. For the pollen exclusion treatment, we encased the inflorescences in 18-in-long × 2-in-diameter (1 in = 2.54 cm) clear plastic pollen tubes, affixed to poles, capped with bridal veil screening on top, and partially sealed at the bottom with duct tape. Complete sealing was not possible; the tide rose daily above the level of the tubes so they had to be allowed to drain. The tubes were removed 2 weeks later when stigmas were no longer receptive. For the pollen addition treatment, we collected anthers from at least ten plants each morning and pooled them in sterile centrifuge tubes. For three consecutive days (Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday) during the same weeks of the pollen exclusion treatment, we hand pollinated all plants by using a sable brush, haphazardly changing the order of pollination. The pollen was applied to the receptive stigmas of the bisexual florets, each of which has the potential to form a single seed. Stigmas are receptive for ≈3 days, and the inflorescence for ≈10 days as the hundreds of florets ripen from top to bottom. We collected all treated inflorescences 4 weeks after manipulations. Seed set is expressed as the number of seeds per all florets per inflorescence.

Stigma Pollen Loads. To determine relative pollen loads of isolated and meadow plants, we collected inflorescences with receptive stigmas from all experimental plants, as well as additional plants in the Palix River and two other areas within the bay. For week 1's plants, we collected inflorescences on all 3 pollen-addition days from plants that had pollen-exclusion tubes and on 2 of the days from plants without exclusion tubes. For week 2, we collected inflorescences on 2 of the pollen-addition days. We collected inflorescences from 50 additional plants at the Palix River, half isolated and half meadow on any given day, over 3 days the week between the manipulations. We also collected from two additional sites, 40 plants at Bone River and 20 from Cedar Creek, in the week after week 2's manipulations. The Bone site is ≈1.5 km north of the Palix River mouth, also on the eastern shore of the bay. The Cedar Creek site is ≈11.5 km northwest of the Palix on the northern shore of the bay. At the Palix and Bone sites, the isolated plants were windward of the meadow plants and leeward at the Cedar site. It rained only on the day, and previous 3 days, that we collected from the Cedar site. It did not rain on the 3 days before, or during, the day of any other stigma collections.

We removed half (one lobe) of three stigmas from each inflorescence of three inflorescences per collection and applied Calberla's pollen stain, which contains basic fuschin (Surveillance Data, Plymouth Meeting, PA). We squashed each stigma lobe and counted the total number of pollen grains. We observed only rarely one other type of pollen that was easily distinguishable from Spartina pollen. The lack of other species' pollen was presumably due to there being only water and mudflats upwind. The wind along the North American Pacific coast is typically onshore and laminar (horizontal and smooth) except during the winter. Inland sites will typically have much more vertical and other directional movement than coastal sites, due to thermal activity and turbulence caused by obstructions, affecting the pattern of pollen deposition (31, 32).

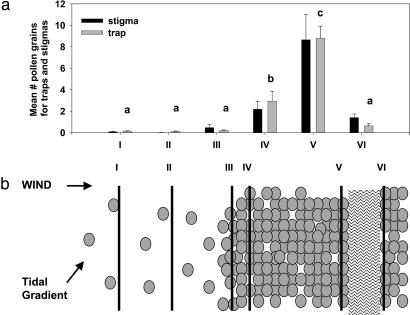

Pollen Traps and Stigmas. To determine the relationship between pollen borne on the wind and that reaching stigmas, we trapped pollen on an array of pollen traps and collected adjacent stigmas across a leeward to windward gradient of plant density, dissected by a 100-m-wide channel at the leeward end (Fig. 2b). The array consisted of six transects oriented to span the gradient in Spartina density and the direction of the prevailing wind: two in windward-isolated plants (I and II), one along the windward meadow edge (III), one in the windward meadow (IV), one in the leeward meadow (V), and one 100 m from the leeward side of the meadow across a channel (VI) (Fig. 2). Each transect was composed of 10 traps spaced 30 m apart. Traps were 10-cm × 10-cm sheets of clear acetate rolled into cylindrical sleeves and attached to 50-ml centrifuge tubes. We coated traps marked with each cardinal direction with a thin layer of aerosol Tangle-Trap (Tanglefoot Co., Grand Rapids, MI) and fixed them atop lengths of electrical metallic tubing at a height of 2 m, just above surrounding inflorescences to prevent inflorescences banging against the traps.

Fig. 2.

Mean pollen loads (+1 SE) on pollen traps and stigma lobes (a) and schematic of trap transect setup (b). Lines on the schematic (b) correspond to trap transects on graph windward to leeward (I–VI). Small circles represent plants. The wavy lines represent an unvegetated channel. Stigma lobe pollen loads (black) on the graph (a) are provided for purposes of visual comparison. For each trap transect of pollen traps (gray), bars with different letters are statistically different at P < 0.05 according to Tukey pairwise comparisons. Close correspondence between trap field-of-view and stigma lobe pollen loads is coincidental.

We set traps on 3 days (August 29, September 3, and September 4). In addition, on September 4 we collected inflorescences for stigma pollen counts from eight plants along each of the trap transects. These inflorescences were collected and processed as above. On each day, we set traps at 0700 hours and collected them 7 h later. This time period corresponded to one low-tide cycle where all inflorescences were above water. All 60 traps were set within 30 min and collected in reverse order. We measured wind direction at a height of 2 m every half hour to assess the general wind direction over the duration of the 3 days that the traps were out (Fig. 2b). After 7 h, the exposed acetate sleeves were laid flat and covered with a clean piece of acetate. We cut the sheets into four 2-cm × 10-cm strips corresponding to the four cardinal directions. We counted stained pollen grains in three nonoverlapping haphazardly chosen fields of view (19.635 mm2) per strip under ×4 magnification and averaged the fields of view for a mean pollen load per trap.

Data Analyses. To determine whether the pollen-addition and pollen-exclusion treatments caused differences in seed set for isolated and meadow plants, we performed a 2-way unbalanced ANOVA with the factors of density, whether isolated or meadow, and treatment (exclusion, addition, ambient). The random variable “plant” was nested within density. Seed set was log-transformed and weighted with the total number of florets of each inflorescence. Differences between pollen treatments were explored by using post hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons. This and all other analyses were performed with sas 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

To test whether isolated and meadow plants had different mean stigma lobe pollen loads per inflorescence, we used an unbalanced ANOVA with the factors of density, whether isolated or meadow, and site (Palix River, Cedar River, and Bone River), the interaction between the two and the random variable “plant,” which is nested within the interaction. We logtransformed pollen loads. We did not attempt comparisons between sites because collections at the sites took place on different days under different conditions.

To test whether pollen loads on traps and stigmas among the six trap transects were correlated, we used a Pearson's correlation procedure. Then, to find whether there were windward to leeward differences in pollen loads among trap transects, we performed a one-way ANOVA with individual trap nested within trap line. We log-transformed pollen trap loads and compared pairwise differences between trap transects with a post hoc Tukey comparison.

Results and Discussion

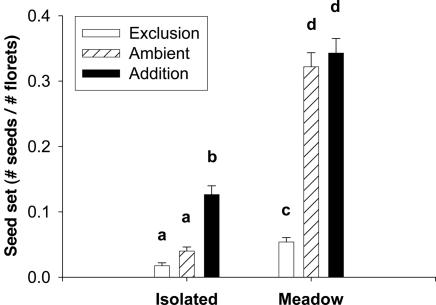

In meadow plants, the pollen-exclusion treatment reduced seed set by >6-fold (P < 0.0001) but caused no reduction in the isolated plants (P = 0.89). The few seeds that were set within the exclusion tubes could have been due to pollen leaking in through the open bottom of the tubes and/or by geitonogamous pollen transfer within inflorescences. S. alterniflora is largely self-incompatible (33) although the Willapa Bay population exhibits a relatively greater capacity to set self-fertilized seed in greenhouse studies than do plants from the native range (H.G.D., unpublished data). The pollen addition treatment had no effect on seed set of meadow plants (P = 0.65) but did raise that of isolated plants by >3-fold (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). We added pollen for only 3 of the potential 10 days of stigma receptivity per inflorescence, because we were restricted to the concurrent timing of low tides and anther dehiscence. That seed set of the isolated plants' addition treatment was not as high as that of the meadow plants' addition and control treatments could be explained by our inability to saturate inflorescences with pollen. However, the results indicate that colonists, isolated plants at low density, are extremely pollen-limited whereas seed set in the high-density meadow is not limited by pollen. A complete table of statistical results of this and following analyses is in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Mean seed set (+1 SE) of pollen exclusion (open), ambient or open-pollinated (hatched), and pollen addition (black) treatments for isolated and meadow plants. Bars with different letters are statistically different at P < 0.01. All treatments were applied to 24 plants, and addition and ambient only to a further 20 plants.

Table 1. Statistical results.

| Analysis | Source | df | Type III MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollen addition and exclusion | Density | 1 | 0.45 | 26.31 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment | 2 | 0.04 | 49.43 | <0.0001 | |

| Density × treatment | 2 | 0.02 | 21.74 | <0.0001 | |

| Plant (density) | 42 | 0.02 | 28.24 | <0.0001 | |

| Error | 427 | 0.0008 | |||

| Total | 474 | ||||

| Stigma pollen | Density | 1 | 15.32 | 95.29 | <0.0001 |

| Site | 2 | 4.87 | 30.04 | <0.0001 | |

| Density × site | 2 | 1.21 | 7.46 | 0.0008 | |

| Plant (density × site) | 148 | 0.19 | 3.13 | <0.0001 | |

| Error | 463 | 0.06 | |||

| Total | 616 | ||||

| Pollen trap | Trap transect | 5 | 2.51 | 23.19 | <0.0001 |

| Trap (trap transect) | 54 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1.0000 | |

| Error | 101 | 0.10 | |||

| Total | 160 |

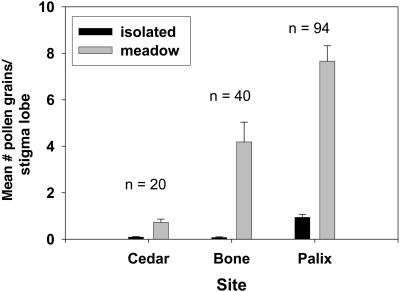

Stigma lobes of meadow plants (overall mean ± SE, 6.31 ± 0.51, n = 77) captured more than nine times the pollen of isolated plants (overall mean ± SE, 0.69 ± 0.09, n = 77) (P < 0.0001) (see Fig. 4). Although sites differed in overall pollen receipt, meadow plants (Palix mean ± SE, 7.66 ± 0.66, n = 47; Bone mean ± SE, 4.18 ± 0.85, n = 20; Cedar mean ± SE, 0.72 ± 0.14, n = 10) always had relatively higher pollen loads than isolated plants, these having on average less than one pollen grain per stigma lobe (Palix mean ± SE, 0.94 ± 0.13, n = 47; Bone mean ± SE, 0.07 ± 0.03, n = 20; Cedar mean ± SE, 0.09 ± 0.03, n = 10). Our work suggests that the small amount of pollen reaching colonists is insufficient for seed set. A threshold of pollination intensity needed for successful seed production has been documented from many other species (32). The very low amount of pollen on Cedar River stigmas, collected after 3 days of rain, suggests that weather could have a profound effect on within- and among-year variation in seed set. Pollen flow is also likely to be inhibited when high tides cover inflorescences during warm and sunny times of day, or directly before.

Fig. 4.

Mean number of pollen grains per stigma lobe (+1 SE) for each inflorescence of isolated and meadow plants at three sites. Untransformed data were used to generate graph. Plant densities are different at P < 0.0001. No comparisons were attempted between sites.

We found a high correlation between pollen loads on the traps and on the stigmas (r = 0.99, P = 0.0002, n = 6). This finding supports the simplest hypothesis that the amount of pollen in the air determines that on stigmas. We also found that pollen loads on traps were highly influenced by transect location (Fig. 2). The wind blew consistently from the same northwest direction (Fig. 2b) over the 3 days the pollen traps were out. There was very little airborne pollen anywhere in the field of isolated colonists, with no more at the leeward end than at the windward end. The pollen load at the meadow edge, where only isolated plants were upwind, was no higher than that of the colonists. Pollen loads increased sharply on the traps inside the meadow, more so further downwind, but dropped precipitously across the unvegetated channel to levels as low as those among isolated plants. This result suggests that effective pollination drops off rapidly with distance from pollen sources.

Our work raises the possibility of pollen limitation in other wind-pollinated plants and could have particular importance for invaders. It directs attention that Allee effects can slow rates of colonization at the fronts of invasions of such plants (29). An Allee effect could contribute to a lag time between introduction and rapid spread that could offer a window of opportunity for control and management. At the same time, such a lag might induce a false sense of security about introduced plants that might become aggressive invaders. Native wind-pollinated plants could also suffer from the effects of pollen limitation as populations fragment due to human-mediated habitat loss or when they compete for space with invaders. A final implication is that pollen limitation in wind-pollinated plants could be an important selective agent influencing the evolution of life history traits (19).

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Ayres, S. Barrett, J. Civille, B. Couch, D. Lövey, I. Parker, and E. Strong for their assistance and advice. This work was supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Center for Environmental Research, Science to Achieve Results (STAR) Program (to H.G.D.), a National Science Foundation (NSF) Biocomplexity Grant (to P. I. A. Hastings), a Washington State Sea Grant (to D.R.S.), and the NSF Integrative Graduate Education and Research Trainee (IGERT) program (to H.G.D. and C.M.T.).

See Commentary on page 13695.

References

- 1.D'Antonio, C. M. & Vitousek, P. M. (1992) Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burd, M. (1994) Bot. Rev. 60, 83–139. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson, B. M. H. & Barrett, S. C. H. (2000) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 69, 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman, A. J. (1947) Heredity 1, 303–335. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gleaves, J. T. (1973) Heredity 31, 355–366. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin, D. A. & Kerster, H. W. (1974) Evol. Biol. 7, 139–220. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rognli, O. A., Nilsson, N.-O. & Nurminiemi, M. (2000) Heredity 85, 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison, T. D. (1990) Ecology, 71, 516–522. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giddings, G. D., Sackville-Hamilton, N. R. & Hayward, M. D. (1997) Theor. Appl. Genet. 94, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giddings, G. D., Sackville Hamilton, N. R. & Hayward, M. D. (1997) Theor. Appl. Genet. 94, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tufto J., Engen, S. & Hindar, K. (1997) Theor. Pop. Biol., 52, 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunin, W. E. (1993) Ecology 74, 2145–2160. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamont, B. B., Klinkhamer, P. G. L. & Witkowski, E. T. F. (1993) Oecologia 94, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widen, B. (1993) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 50, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aizen, M. A. & Feinsinger, P. (1994) Ecology 75, 330–351. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ågren, J. (1996) J. Ecol. 77, 1779–1790. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunin, W. E. (1997) J. Ecol. 85, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groom, M. J. (1998) Am. Nat. 151, 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig, W. D. & Ashley, M. V. (2003) Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 157–159. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp, E. E., Goedde, M. A. & Rice, K. J. (2001) Oecologia 128, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sork, V. L., Davis, F. W., Smouse, P. E., Apsit, V. J., Dyer, R. J., Fernandez, J. F. & Kuhn, B. (2002) Mol. Ecol. 11, 1657–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson, S. G. & Wästljung, U. (1987) Ecology 68, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hastings, A. (1996) Biol. Cons. 78, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker, I. M. (1997) Ecology 78, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allee, W. C. (1931) Animal Aggregations: A Study in General Sociology (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago).

- 26.Stephens, P. A., Sutherland, W. J. & Freckleton, R. P. (1999) Oikos 87, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, M. H. & Kot, M. (2001) Math. Biosci. 171, 83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, M. H., Kot, M. & Neubert, M. G. (2002) J. Math. Biol. 44, 150–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor, C. M., Davis H. G., Civille, J. C., Grevstad, F. S. & Hastings, A. (2004) Ecology, in press.

- 30.Davis, H. G., Taylor, C. M., Civille, J. C. & Strong, D. R. (2004) J. Ecol. 92, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nurminiemi, M., Tufto, J., Nilsson, N.-O. & Rognli, O. A. (1998) Evol. Ecol. 12, 487–502. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hessing, M. B. (1988) Am. J. Bot. 75, 1324–1333. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somers, F. G. & Grant, D. (1981) Am. J. Bot. 68, 6–9. [Google Scholar]