Abstract

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) family members, including epiregulin (EP), play a fundamental role in epithelial tissues; however, their roles in immune responses and the physiological role of EP remain to be elucidated. The skin has a versatile system of immune surveillance. Biologically active IL-1α is released to extracellular space upon damage from keratinocytes and is a major player in skin inflammation. Here, we show that EP is expressed not only in keratinocytes but also in tissue-resident macrophages, and that EP-deficient (EP–/–) mice develop chronic dermatitis. Wound healing in the skin in EP–/– mice was not impaired in vivo, nor was the growth rate of keratinocytes from EP–/– mice different from that of WT mice in vitro. Of interest is that in WT keratinocytes, both IL-1α and the secreted form of EP induced down-regulation of IL-18 mRNA expression, which overexpression in the epidermis was reported to induce skin inflammation in mice, whereas the down-regulation of IL-18 induced by IL-1α was impaired in EP–/– keratinocytes. Although bone marrow transfer experiments indicated that EP deficiency in non-bone-marrow-derived cells is essential for the development of dermatitis, production of proinflammatory cytokines by EP–/– macrophages in response to Toll-like receptor agonists was much lower, compared with WT macrophages, whose dysfunction in EP–/– macrophages was not compensated by the addition of the secreted form of EP. These findings, taken together, suggested that EP plays a critical role in immune/inflammatory-related responses of keratinocytes and macrophages at the barrier from the outside milieu and that the secreted and membrane-bound forms of EP have distinct functions.

The system of epidermal growth factor (EGF) superfamily (1) and EGF receptor (EGFR) family, including EGFR (ErbB1), ErbB2 (HER2), ErbB3 (HER3), and ErbB4 (HER4) (2), play a fundamental role in epithelial tissues. EGF family members, including EGF, transforming growth factor-α, amphiregulin, heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF), epiregulin (EP), and other members, regulate these receptors by inducing their homo- and/or heterooligomerization (2, 3). EGF family members vary in their ability to activate distinct ErbB heterodimers, and this mechanism may, in part, account for the differences in their bioactivities (4–7).

The membrane-anchored precursor of the EGF family is enzymatically processed externally to release a mature soluble form that acts as autocrine and/or paracrine growth factor (8, 9), whereas some members of the EGF family act in the membrane-anchored form (8, 10). A bioactive transmembrane precursor, pro-HB-EGF, was suggested to induce growth inhibition or apoptosis rather than the proliferative response induced by soluble HB-EGF (10). EP (11–17) acts as an autocrine growth factor in normal human keratinocytes in vitro (15); however, its physiological role in vivo still remains to be elucidated.

Keratinocytes in the epidermis play critical roles in the cutaneous immune-related responses (18) and contain biologically active IL-1α (19), which is released to extracellular space upon damage and is a major player in skin inflammation (20). Overexpression of IL-1α in murine epidermis produces inflammatory skin lesions, indicating the critical role of IL-1α in skin inflammation (21). On the other hand, IL-18 is stored as a biologically inactive precursor form in keratinocytes, and overexpression of IL-18 in the mouse skin was reported to induce inflammatory skin lesions without inducing allergen-specific IgE production (22).

Macrophages normally reside in tissues and beneath mucosal surfaces and function at the front line of immune defense against incoming pathogens through ingestion of bacteria by phagocytosis, destruction of bacteria, and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of infection by using soluble mediators (23). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (24, 25), which recognize molecular patterns that are common and shared by many microbial pathogens, are expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including macrophages and dendritic cells: TLR4 to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TLR2 to peptidoglycan (PGN), and TLR9 to CpG DNA.

Here, we show the critical role of EP in immune/inflammatory-related responses of keratinocytes and macrophages through the establishment and analysis of EP–/– mice.

Methods

Generation of EP-Deficient Mice. We isolated the genomic DNA of the EP gene from a 129/Sv mouse genomic library (Stratagene) and constructed the targeting vector by replacing a 6.5-kb SalI-XhoI fragment containing exons 2–5 (90% of the coding region) of the EP gene, with a pGKneo cassette with opposite transcriptional orientation. The 5′ and 3′ arm of the targeting construct was composed of 2.0-kb and 11.0-kb genomic DNA, respectively. Diphtheria-toxin A fragment cassette (DT-A) flanked the 3′ genomic arm. The targeting vector was linearized with SalI. The mutant embryonic stem cells were microinjected into C57BL/6 blastocysts as described (26), and the resulting male chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 mice. Heterozygous offspring were intercrossed to obtain EP-deficient mice.

Histopathology. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded on paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Mast cells and eosinophils were detected by toluidine blue and Luna staining, respectively.

Quantification of Serum Ig Isotype Concentration. Blood samples were obtained from mouse eye vein. Serum Ig isotype concentration was determined by using an ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX).

Preparation of Mice Macrophages and Keratinocytes. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated as described (27). Bone marrow-derived macrophages were generated as described (28). Primary epidermal keratinocytes were prepared from neonatal foreskins as described (29), then cultured on plates coated with 30 μg·ml–1 type I collagen (TOYOBO, Tokyo) in Keratinocytes-SFM (GIBCO/BRL) with 50 ng·ml–1 bovine pituitary extract (BPE), 10 ng·ml–1 recombinant murine EGF (Sigma), and 0.03 mM CaCl2 (9). Keratinocytes (2 × 105 per well in a 24-well plate) were cultured without BPE and EGF for 24 h, then stimulated with recombinant mouse EP (rmEP) (R & D Systems) or recombinant mouse IL-1α (PeproTech), and mRNA expressions were determined by RT-PCR.

Quantification of Cytokine Concentration of the Culture Supernatants.Peritoneal macrophages (5 × 105 per well) or bone marrow-derived macrophages (5 × 105 per well) were cultured in 12-well plates for 24 h, then stimulated with rmEP, LPS, PGN, or CpG [LPS from Salmonella typhimurium (Sigma); PGN from Staphylococcus aureus (Fluka); CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCT-GATGCT-3′) (Sigma)]. The culture supernatants were subjected to IL-6, IL-12p40, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α by ELISA kit (BioSource International).

Isolation of RNA and RT-PCR. Epidermis was isolated from the ear. T, B, CD11b+, and CD11c+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Total RNA from the tissues and sorted cells were isolated by ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan), and total RNA from primary epidermal keratinocytes and bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) were isolated by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase (Qiagen), and PCR was done by using LAtaq polymerase (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto) and gene-specific primers: for EP, 5′-TTGGGTCTTGACGCTGCTTTGT-3′ and 5′-TGAGGTCACTCTCATATTC-3′;for IL-18,5′-ATGGCTGC-CATGTCAGAAGACTCT-3′ and 5′-ACTCCATCTTGTTGT-GTCCTGGAAC-3′; for TLR2, 5′-TCTCCTGTTGATCTT-GCTCGTAGG-3′ and 5′-TTACCCAAAACACTTCCT-GCTGGC-3′; for TLR4 5′-TCAGTCTTCTAACTTCCCTC-CTGC-3′ and 5′-AGCTGTCCAATAGGGAAGCTTTCT-3′; for NOD1, 5′-CAGATAACTGATATCGGAGCCAGG-3′ and 5′-TTTGGCCTCCTCGGGCTTAATCAA-3′; for NOD2, 5′-AAGCAGAACTTCTTGTCCCTGAGG-3′ and 5′-TCACAA-CAAGAGTCTGGCGTCCCT-3′; for MD2, 5′-ATGTT-GCCATTTATTCTCTTTTCGACG-3′ and 5′-ATTGACAT-CACGGCGGTGAATGATG-3′; GAPDH primers were from Clontech. The optimal cycle number for each gene was determined empirically under nonsaturating conditions.

Measurement of T Cell Responses and Growth Rate of Keratinocytes.CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleens of mice immunized with 100 μg of ovalbumin (OVA) emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant after 14 days. CD4+ T cells (4 × 105 cells) were incubated with irradiated peritoneal macrophages (5 × 105 cells) in 96-well plates at the indicated concentration of OVA in RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% FCS for 72 h. They were pulsed with 1 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) [3H]thymidine for the final 12 h, and radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting (30). For proliferation assay, primary epidermal keratinocytes (4 × 104 cells) were plated on a type I collagen-precoated 96-well plate and cultured in the presence of 10 ng·ml–1 EGF, then pulsed with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine for the final 8 h, and radioactivity was measured by using liquid scintillation counting (29).

Phagocytosis Assay. Mouse peritoneal macrophages (5 × 106 ml–1) were incubated for 60 min at 37°C in the presence of 0.75 μM fluorescent beads (Polysciences). These cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice and fixed with 2.5% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min on ice. Phagocytosis was measured by the percentage of phagocytic cells per 100 cells by fluorescent microscopy, as described (31).

Cell Staining and Flow Cytometry. Single-cell suspensions were incubated at 2 × 105 cells per 100 μl on ice in staining buffer (PBS containing 2.5% FCS and 0.01% NaN3) with the mAbs for 15 min (28). The mAbs used were anti-I-Ab, anti-CD80, anti-CD86, anti-CD40, and anti-CD11b (Pharmingen). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Bone Marrow Transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation experiments were done as described (32). In brief, bone marrow cells were isolated from EP–/– and WT mice, and recipient mice were irradiated (11 Gy) 12 h before injection (i.v.) of 2 × 107 donor bone marrow cells.

Results

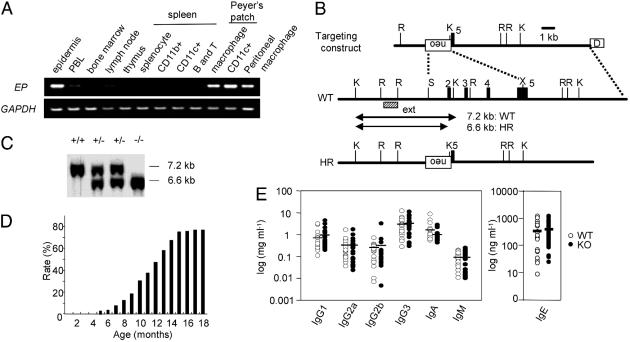

EP Expression in Epidermis and Tissue-Resident APCs. Because human EP mRNA is expressed predominantly in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) (12), mouse EP expression in immune-related tissues was examined by RT-PCR. Mouse EP expression was detected not only in the epidermis (15) but also in peritoneal macrophages, and in macrophages and CD11c+ dendritic cells in Peyer's patches (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, EP was rarely detected in the immune system, including bone marrow, thymus, lymph nodes, and spleen (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, mouse EP expression in PBL was much lower, compared with that in tissue-resident APCs (Fig. 1A). These results suggested that EP may be involved in the functions of keratinocytes in the epidermis and tissue-resident APCs.

Fig. 1.

EP expression in mouse immune-related tissues and generation of EP-deficient mice. (A) EP expression level was determined by using RT-PCR with GAPDH as control. PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes. (B) Schematic representations of targeting construct, WT EP genomic DNA, and homologous recombinant (HR) allele. The numbers denote exons (filled boxes). External probe (ext) used in Southern blot to detect HR events is indicated by a dashed box. The germ-line and recombinant KpnI restriction fragments are denoted by lines with arrowheads. Restriction sites: K, KpnI; R, EcoRI; S, SalI; X, XhoI; neo, pGK-neo; D, diphtheria toxin A fragment. (C) Southern blot of KpnI-digested genomic DNA with the external probe. (D) The rate of chronic dermatitis observed in EP–/– mice. (E) Serum Ig isotype concentration. Serum Ig isotype concentration was determined by ELISA. WT mice (open circles; n = 22) and EP–/– mice without dermatitis (filled circles; n = 20) at the age of 4 months. Mean values are indicated by short horizontal lines.

EP Deficiency Results in Dermatitis in Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF) Conditions. To elucidate the function of EP in vivo, EP-deficient mice were generated, in which 90% of the coding region was deleted (Fig. 1 B and C). EP–/– mice were born from heterozygous matings and seemed to be indistinguishable from WT mice. However, EP–/– mice had chronic dermatitis at age 5 months at the earliest, even under SPF conditions. The rate of dermatitis observed in EP–/– mice was ≈20%, 50%, and 75% at the age of 9 months, 12 months, and 15 months, respectively, in the mixed genetic background of 129SV/J and C57BL6/J (Fig. 1D), suggesting that a genetic background and/or environmental factors affect the development of dermatitis in EP–/– mice.

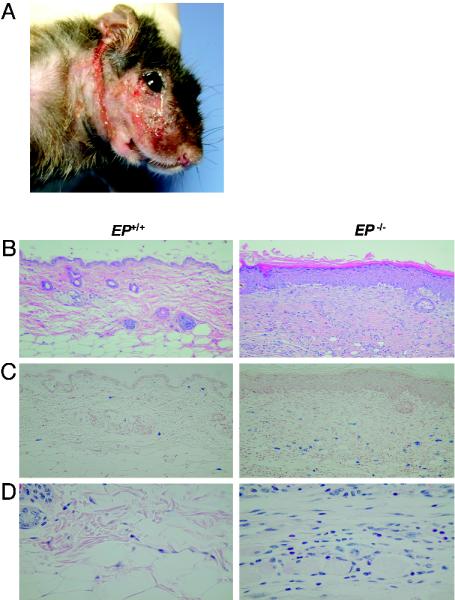

Pathology of the Skin Legions in EP–/– Mice. Most of the skin lesions started as focal skin alterations in the ears or faces and gradually extended to the necks (Fig. 2A). The pathological findings of the skin legions in EP–/– mice were typical chronic dermatitis characterized by thickness of epithelial layers and fibrosis with infiltration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 2B), including mast cells (Fig. 2C) and eosinophils (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Pathology of the skin legions in EP-deficient mice. (A) Chronic dermatitis around the face of EP–/– mice (8 months of age). (B–D) Chronic dermatitis in skin in EP–/– mice. Sections of skin were subjected to staining with hematoxylin/eosin (B), toluidine blue staining for mast cells (C), and Luna staining for eosinophils (D).

Serum Ig and Cytokine Concentrations in EP–/– Mice. Serum Ig isotype concentrations, including IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, IgM, and IgE, in EP–/– mice were not different from WT mice (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the serum concentrations of cytokines, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12, IL-13, IL-18, TNF-α, and IFN-γ did not differ between WT and EP–/– mice without dermatitis (data not shown). All these results suggested that dermatitis in EP–/– mice is not IgE-dependent and systemic immunological disturbance might not exist in EP–/– mice.

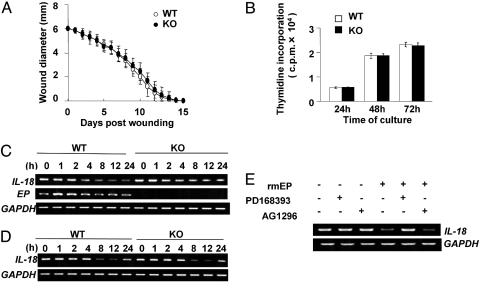

Wound Healing Was Not Impaired in EP–/– Mice. Although EP was reported to be involved in tissue repairing and growth of keratinocytes, wound healing in EP–/– mice was not impaired in vivo (Fig. 3A), nor was the growth rate of keratinocytes from EP–/– mice different from that of WT mice in vitro (Fig. 3B). These findings taken, together, suggested that EP will not play a crucial role in the growth of keratinocytes in vivo, which will be possibly due to the functional redundancy of the EGF family.

Fig. 3.

Disturbance of IL-1α-induced down-regulation of IL-18 mRNA expression in EP–/– mice-derived keratinocytes. (A) Wound healing in WT and EP–/– mice. A full-thickness skin excision (6 mm in diameter) was made on the back of WT (open circles; n = 10) and EP–/– (filled circles; n = 10) mice. Values indicate the mean diameter ± SD. (B) Proliferation of primary epidermal keratinocytes from WT (open bars) and EP–/– (filled bars) mice. Keratinocytes (4 × 104 per well in a 96-well plate) were cultured, and cell proliferation at the indicated times was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Data shown in triplicate are the mean ± SD. (C and D) Down-regulation of IL-18 mRNA expression by IL-1α (C) and EP (D) in primary keratinocytes. Keratinocytes (2 × 105 per well in a 24-well plate) were stimulated with 50 ng·ml–1 recombinant mouse IL-1α (C) and 100 ng·ml–1 rmEP (D) for the indicated time, and the expressions were determined by using RT-PCR. Experiments were repeated five times with similar results. (E) Down-regulation of IL-18 expression by EP depends on EGFR. Keratinocytes (2 × 105 per well in a 24-well plate) were preincubated with 2 μM of PD168393 (Calbiochem), 2 μM of AG1296 (Calbiochem), or vehicle for 30 min, followed by incubation with 100 ng·ml–1 rmEP in culture medium for 12 h. The expressions were determined by using RT-PCR.

Induction of EP mRNA Expression and Down-Regulation of IL-18 mRNA Expression in Keratinocytes by IL-1α. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which EP deficiency leads to dermatitis, we next analyzed the inflammatory responses of primary keratinocytes stimulated with IL-1α (21). IL-1α induced EP mRNA expression at 1 h after stimulation, and it was recovered to the basal level at 8 h after stimulation (Fig. 3C). Of note is that IL-1α evidently reduced the expression of IL-18 mRNA at 4 h after stimulation in WT-derived keratinocytes and the reduced IL-18 expression was still observed at 24 h after stimulation, whereas the decreased IL-18 expression in EP–/– keratinocytes was not prominent, compared with the finding in WT keratinocytes (Fig. 3C). These results, together, suggested that IL-1α-induced down-regulation of IL-18 expression is impaired in keratinocytes of EP–/– mice.

Down-Regulation of IL-18 mRNA Expression Induced by the Secreted Form of EP. To elucidate whether the secreted form of EP (sEP) affects the down-regulation of IL-18 expression, keratinocytes were stimulated with rmEP. rmEP reduced IL-18 expression in WT- and EP–/–-derived keratinocytes at 8 h after stimulation, and there was no obvious difference between WT and EP–/– (Fig. 3D). The expressions were still reduced at 24 h after stimulation in both keratinocytes, although their expressions were gradually increased at 24 h (Fig. 3D). These results, together, suggested that IL-1α-induced down-regulation of IL-18 will be, in part, dependent on sEP. Furthermore, preexposure of keratinocytes with an EGFR kinase blocker (PD168393) (33) prevented rmEP-induced down-regulation of IL-18 expression, whereas a platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) blocker (AG1296) as a control did not do so (Fig. 3E). These findings, together, suggested that sEP down-regulates the IL-18 expression through EGFR in keratinocytes and that loss of EP leads to the disturbance of tight regulation of IL-18 expression in keratinocytes, which will, in part, cause the development of dermatitis in EP–/– mice.

Loss of EP in Non-Bone-Marrow-Derived Cells Is Essential for the Development of Dermatitis. To elucidate that EP expression in which cells, keratinocytes, or bone marrow-derived cells including macrophages is essential for the proper homeostasis of the skin region, bone marrow transfer experiments were done. The chimera mice, in which WT-derived bone marrow cells were transplanted into EP–/– mice, developed dermatitis, but not vice versa (Table 1), suggesting that loss of EP in non-bone-marrow-derived cells will be essential for the development of dermatitis and that EP expression in keratinocytes may be critical for the homeostasis of the skin.

Table 1. Bone marrow transplantation.

| Recipient | Donor | Dermatitis* |

|---|---|---|

| WT | EP-/- | 0/7 |

| EP-/- | WT | 8/10 |

The number of mice with dermatitis was determined 6 months after transplantation.

The number of mice with dermatitis/the number of recipients.

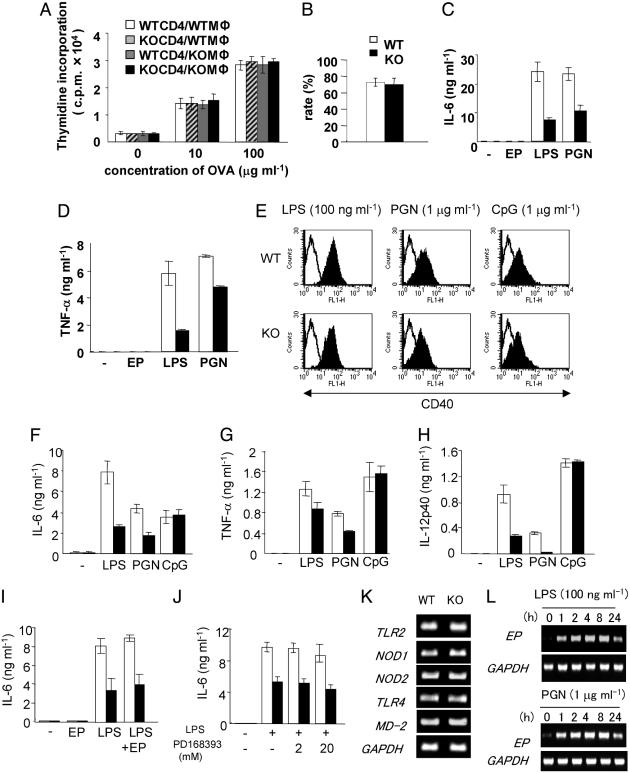

Antigen Presentation and Phagocytosis of Peritoneal Macrophages. As EP was strongly expressed in tissue-resident macrophages (Fig. 1A), we focused on the functions of peritoneal macrophages. First, we examined the potential of antigen presentation of macrophages through T cell responses to the antigen by using immunized mice with ovalbumin. There was no significant difference in proliferation of T cells from the immunized WT and EP–/– mice, when stimulated by WT- or EP–/–-derived peritoneal macrophages with ovalbumin (Fig. 4A), indicating that antigen presentation of macrophages and the T cell responses were not impaired in EP–/– mice. Furthermore, the potential of phagocytosis was not impaired in macrophages from EP–/– mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

TLR agonist-induced proinflammatory cytokine production in macrophages. (A) Shown are proliferative responses of T cells to the immunized antigen presented by macrophages. T cell proliferation to the irradiated peritoneal macrophages with the indicated concentration of ovalbumin was evaluated by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Mφ, macrophage. (B) Activity of phagocytosis of macrophages. Phagocytosis of fluorescent beads by macrophages was determined by using fluorescent microscopy. Solid bars, EP–/– mice; open bars, WT mice). The values are the means ± SD of three independent experiments. (C and D) Production of IL-6 (C) and TNF-α (D) by the peritoneal macrophages stimulated with LPS (100 ng·ml–1), PGN (10 μg·ml–1), and EP (100 ng·ml–1). Cytokine concentration in the supernatant after 24 h was examined by using ELISA. Experiments were repeated five times in triplicate with similar results. Data shown in triplicate are the mean ± SD. Shown are WT (open bars) and EP–/– (filled bars). (E) Surface expression of CD40 on the BMDM stimulated with LPS (100 ng·ml–1), PGN (1 μg·ml–1), and CpG (1 μg·ml–1). Expressions were determined at 24 h after stimulation by FACS. (F–H) Production of IL-6 (F), TNF-α (G), and IL-12p40 (H) by the BMDM stimulated with LPS, PGN, and CpG, respectively. (I) Production of IL-6 by the BMDM stimulated by rmEP (100 ng·ml–1) in addition to LPS stimulation. (J) Production of IL-6 by the BMDM stimulated with LPS in the presence of EGFR blocker. BMDM (5 × 105 per well in 12-well plates) were preincubated with 2μM or 20 μM of PD168393 for 30 min, followed by stimulation with LPS (100 ng·ml–1). Cytokine concentration in the supernatant after 24 h was examined by using ELISA. Experiments were repeated five times in triplicate with similar results. Data shown in triplicate are the mean ± SD. Shown are WT (open bars) and EP–/– (filled bars). (K) Expression of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1), NOD2, and MD-2 in BMDM from WT and EP–/– mice. The expressions were determined by RT-PCR. (L) Induction of EP expression by LPS and PGN in peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng·ml–1 LPS and 1 μg·ml–1 PGN for the indicated time, and the expressions were determined by RT-PCR.

Low Responsiveness to TLR Agonists in Proinflammatory Cytokine Production by EP–/– Peritoneal Macrophages. To elucidate a possibility that EP is involved in the innate immunity, we examined TLR signaling in macrophages. LPS induced surface expressions of CD80, CD86, and CD40, by peritoneal macrophages from WT and EP–/– mice, and differences were not observed between WT and EP–/– (data not shown). However, IL-6 and TNF-α productions were remarkably reduced in macrophages from EP–/– mice in response to LPS and PGN, compared with findings in WT mice (Fig. 4 C and D).

Membrane-Anchored EP, but Not Secreted EP, May Play Critical Roles in LPS- and PGN-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Production by Macrophages. To elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying the low responsiveness to TLR agonists, we analyzed BMDM. The three TLR agonists, including LPS, PGN, and CpG, induced the MHC class II molecule I-Ab and costimulatory molecules, including CD80, CD86, and CD40, by WT- and EP–/–-derived BMDM, and there was no difference in the surface expressions of these molecules between WT- and EP–/–-derived BMDM (Fig. 4E and data not shown). Obvious differences of the responses were observed in the IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α secretion by BMDM between WT and EP–/– mice, when stimulated with LPS and PGN, but not CpG (Fig. 4 F–H). Expression levels of TLR-2, TLR-4, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1), NOD2 (34), and MD-2 (28) in EP–/– mice–derived BMDM were not different from findings in WT mice (Fig. 4K). These results, together, suggested that EP affects the TLR4- and TLR2-mediated signaling in macrophages.

Furthermore, the addition of rmEP to LPS stimulation did not show differences in cytokine production, compared with a single LPS stimulation (Fig. 4I), suggesting that sEP does not affect these responses, although LPS and PGN did induce rapid EP expression in macrophages (Fig. 4L). Preexposure of BMDM with high concentration of PD168393 before LPS stimulation seemed to reduce the total amount of IL-6 production (35); however, the obvious difference in IL-6 secretion between WT and EP–/– BMDM still existed (Fig. 4J), indicating that the difference is not dependent on EGFR-mediated signaling. All these results suggested that the membrane-anchored EP will play critical roles in the cytokine production by macrophages and/or in macrophage differentiation (17, 36).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that EP deficiency results in chronic dermatitis in mice and that EP is physiologically a critical molecule for tight control of IL-18 mRNA expression of keratinocytes and for proper production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages in response to LPS and PGN.

Wound healing in the skin in EP–/– mice and the growth of in EP–/– keratinocytes were not impaired (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting that dermatitis in EP–/– mice will be caused rather by the dysregulation of immune-related responses of the skin, but not due to the dysfunction of the proliferative activities of keratinocytes. Skin is the place to be damaged frequently, and indigenous bacteria exist in the epidermis, the barrier from the outside milieu. It is intriguing that a member of the EGF family is critically involved in immune regulation of keratinocytes and macrophages. Elucidation of the functions of the EGF family on APCs and epithelial cells in immune regulation might lead to a better understanding of immune defense at the primary interface between the body and the environment and might provide insight into the pathogenesis of inflammatory epithelial disorders.

IL-1α rapidly induced EP expression in keratinocytes (Fig. 3C) and the skin lesions in EP–/– mice were mostly restricted to faces and ears, suggesting that IL-1α release by repeated grooming-induced injury may accumulate IL-18 in the skin of EP–/– mice, resulting in the initiation of development of dermatitis in EP–/– mice (22). IL-1α alone did not induce the active form of IL-18 by primary keratinocytes (data not shown), suggesting that some particular signals, in addition to IL-1α, may be necessary for the production of the active form of IL-18 by keratinocytes. On the other hand, dysregulation of IL-18 expression in the skin legions in EP–/– mice in vivo was not constantly observed (data not shown), suggesting that dysregulation of IL-1α-induced IL-18 down-regulation may not be involved in the promotion of dermatitis. Because IL-1α-deficient mice do not develop dermatitis (37), analysis of EP–/–/IL-1α–/– doubly mutant mice will show the relation between IL-1α and EP for the development of dermatitis in EP–/– mice.

Bone marrow transfer experiments supported the critical role of EP in keratinocytes for homeostasis of the skin; however, there are possibilities that EP by keratinocytes might affect the function and/or differentiation of tissue-resident macrophages and that loss of EP in macrophages might affect the progression of dermatitis.

Although EP expression in other epithelial tissues was not extensively examined in this study, there is a possibility that EP might be involved in immune/inflammatory responses in other epithelial tissues, including intestine and lung. Dendritic cells (DCs) initiate and regulate immune responses, linking innate and adaptive immunity (38). EP expression in Langerhans cells, the DCs in epidermis (39, 40), was not determined in this study, whereas EP expression in DCs in Peyer's patches was strongly observed. There might be a possibility that EP plays a crucial role not only in DCs in Peyer's patches but also in Langerhans cells.

The sEP is involved in the IL-1α-induced down-regulation of IL-18 expression (Fig. 3D) and the mechanism by which sEP regulates IL-18 expression depends on the EGFR (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, addition of sEP or EGFR blocker did not affect the proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages (Fig. 4 I and J), suggesting that the membrane-anchored EP may be involved in the proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages stimulated with LPS and PGN through non-EGFR-mediated signaling. A bioactive membrane precursor, pro-HB-EGF, functions as the diphtheria toxin receptor in primates (41) and distinctively signals growth inhibition or apoptosis rather than the proliferative response induced by soluble HB-EGF (10). Like HB-EGF, sEP and membrane-anchored EP will have distinct function and there might be a possibility that membrane-anchored EP transduces signals into the own cells as receptor (8).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that EP–/– mice are susceptible for the development of dermatitis even in specific pathogen-free conditions and that sEP is critical for the proper regulation of IL-18 in keratinocytes and membrane-anchored EP will be essential for the proper proinflammatory cytokine production in response to LPS and PGN by tissue resident macrophages. Further elucidation of EP function may shed light on epithelial inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kensuke Miyake for critical comments, Y. Yamada for the injections, Y. Fujimoto for technical assistance, M. Ohara for language assistance, and S. Ohkubo and Y. Hagishima for manuscript preparation. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF; EP, epiregulin; rmEP, recombinant mouse EP; sEP, secreted form of EP; TLR, Toll-like receptor; BMDM, bone marrow-derived macrophage; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PGN, peptidoglycan; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; APC, antigen-presenting cell.

References

- 1.Lee, D. C., Fenton, S. E., Berkowitz, E. A. & Hissong, M. A. (1995) Pharm. Rev. 47, 51–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riese, D. J., II, & Stern, D. F. (1998) BioEssays 20, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarden, Y. & Sliwkowski, M. X. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beerli, R. R. & Hynes, N. E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6071–6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riese, D. J., II, Kim, E. D., Elenius, K., Buckley, S., Klagsbrun, M., Plowman, G. D. & Stern, D. F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20047–29952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graus-Porta, D., Beerli, R. R., Daly, J. M. & Hynes, N. E. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1647–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson, L. F., Qiu, T. H., Sunnarborg, S. W., Chang, A., Zhang, C., Patterson, C. & Lee, D. C. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2704–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massagué, J. & Pandiella, A. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62, 515–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sunnarborg, S. W., Hinkle, C. L., Stevenson, M., Russell, W. E., Raska, C. S., Peschon, J. J., Castner, B. J., Gerhart, M. J., Paxton, R. J., Black, R. A., et al. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12838–12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwamoto, R. & Mekada, E. (2000) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 11, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyoda, H., Komurasaki, T., Ikeda, Y., Yoshimoto, M. & Morimoto, S. (1995) FEBS Lett. 377, 403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toyoda, H., Komurasaki, T., Uchida, D. & Morimoto, S. (1997) Biochem. J. 326, 69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelly, M., Pinkas-Kramarski, R., Guarino, B. C., Waterman, H., Wang, L.-M., Lyass, L., Alimandi, M., Kuo, A., Bacus, S. S., Pierce, J. H., et al. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10496–10505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor, D. S., Cheng, X., Pawlowski, J. E., Wallace, A. R., Ferrer, P. & Molloy, C. J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1633–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirakata, Y., Komurasaki, T., Toyoda, H., Hanakawa, Y., Yamasaki, K., Tokumaru, S., Sayama, K. & Hashimoto, K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5748–5753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baba, I., Shirasawa, S., Iwamoto, R., Okumura, K., Tsunoda, T., Nishioka, M., Fukuyama, K., Yamamoto, K., Mekada, E. & Sasazuki, T. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 6886–6889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi, M., Hayashi, K., Yoshida, K., Ohkawa, Y., Komurasaki, T., Kitabatake, A., Ogawa, A., Nishida, W., Yano, M., Monden, M., et al. (2003) Circulation 108, 2524–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker, J. N., Mitra, R. S., Griffiths, C. E., Dixit, V. M. & Nickoloff, B. J. (1991) Lancet 337, 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauser, C., Saurat, J.-H., Schmitt, A., Jaunin, F. & Dayer, J.-M. (1986) J. Immunol. 136, 3317–33321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy, J. E., Robert, C. & Kupper, T. S. (2000) J. Invest. Dermatol. 114, 602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grooves, R. W., Mizutani, H., Kieffer, J. D. & Kupper, T. S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11874–11878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konishi, H., Tsutsui, H., Murakami, T., Yumikura-Futatsugi, S., Yamanaka, K., Tanaka, M., Iwakura, Y., Suzuki, N., Takeda, K., Akira, S., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11340–11345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberger, C. M. & Finlay, B. B. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akira, S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38105–38108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeda, K., Kaisho, T. & Akira, S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirasawa, S., Arata, A., Onimaru, H., Roth, K. A., Brown, G. A., Horning, S., Arata, S., Okumura, K., Sasazuki, T. & Korsmeyer, S. J. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomura, F., Akashi, S., Sakao, Y., Sato, S., Kawai, T., Matsumoto, M., Nakanishi, K., Kimoto, M., Miyake, K., Takeda, K., et al. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 3476–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagai, Y., Akashi, S., Nagafuku, M., Ogata, M., Iwakura, Y., Akira, S., Kitamura, T., Kosugi, A., Kimoto, M. & Miyake, K. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sano, S., Itami, S., Takeda, K., Tarutani, M., Yamaguchi, Y., Miura, H., Yoshikawa, K., Akira, S. & Takeda, J. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4657–4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawahata, K., Misaki, Y., Yamauchi, M., Tsunekawa, S., Setoguchi, K., Miyazaki, J. & Yamamoto, K. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 1103–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn, P. A., Eaton, W. R., Lopatin, E. D., McEntire, J. E. & Papermaster, B. W. (1983) J. Immunol. Methods 64, 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujimoto, Y., Tu, L., Miller, A. S., Bock, C., Fujimoto, M., Doyle, C., Steeber, D. A. & Tedder, T. F. (2002) Cell 108, 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mascia, F., Mariani, V., Girolomoni, G. & Pastore, S. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 163, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Royet, J. & Reichhart, J. M. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13, 610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobbs, R. M. & Watt, F. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19798–19807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon, S. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horai, R., Asano, M., Sudo, K., Kanuka, H., Suzuki, M., Nishihara, M., Takahashi, M. & Iwakura, Y. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 1463–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hackstein, H. & Thomson, A. W. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert, C. & Kupper, T. S. (1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1817–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kupper, T. S. & Fuhlbrigge, R. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naglich, J. G., Metherall, J. E., Russell, D. W. & Eidels, L. (1992) Cell 69, 1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]