The opinions of patients and caregivers who participated in a randomized trial of early palliative care versus standard oncology care, regarding the respective roles of their oncologist (both groups) and palliative care physician (early palliative care group) were solicited. Participants perceived the respective roles of their oncologist and palliative care physician as discrete, important, and complementary for the provision of excellent cancer care.

Keywords: Palliative care, Medical oncology, Qualitative research, Professional role, Ambulatory care

Abstract

Introduction.

Early integration of palliative care alongside oncology is being increasingly recommended, although the strategies and models for integration remain poorly defined. We solicited the opinions of patients and caregivers who participated in a randomized trial of early palliative care versus standard oncology care, regarding the respective roles of their oncologist (both groups) and palliative care physician (early palliative care group).

Materials and Methods.

The study was performed at a comprehensive cancer center. Forty-eight patients (26 intervention, 22 control) and 23 caregivers (14 intervention, 9 control) were recruited purposefully at trial end. One-on-one, semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted and analyzed using grounded theory.

Results.

The themes resulting from the analysis fell into three categories: the focus of care, the model of care delivery, and the complementarity between teams. The focus of care in oncology was perceived to be disease-centered, with emphasis on controlling disease, directing cancer treatment, and increasing survival; palliative care was perceived to be more holistic and person-focused, with an emphasis on symptom management. Oncology visits were seen as following a structured, physician-led, time-constrained model in contrast to the more fluid, patient-led, flexible model experienced in the palliative care clinic. No differences were found in the descriptions of oncology between participants in the intervention and control groups. Participants in the intervention group explicitly described the roles of their oncologist and their palliative care physician as distinct and complementary.

Conclusion.

Participants perceived the respective roles of their oncologist and palliative care physician as discrete, important, and complementary for the provision of excellent cancer care.

Implications for Practice:

Patients and their caregivers who experienced early palliative care described the roles of their oncologists and palliative care physicians as being discrete and complementary, with both specialties contributing to excellent patient care. The findings of the present research support an integrated approach to care for patients with advanced cancer, which involves early collaborative care in the ambulatory setting by experts in both oncology and palliative medicine. This can be achieved by more widespread establishment of ambulatory palliative care clinics, encouragement of timely outpatient referral to palliative care, and education of oncologists in palliative care.

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer have a complex array of physical and psychosocial needs [1] that can arise early in the course of illness [2]. Palliative care services are well-placed to address those needs; however, referrals to palliative care are typically made late in the illness trajectory [3, 4]. A substantial body of quantitative evidence now supports the merits of early palliative care (EPC) for patients with advanced cancer, including improvements in quality of life, mood, satisfaction with care, symptom burden, and, in some cases, survival [5–7]. Thus, early integration of palliative care into oncology care is recommended as the standard of care by an increasing number of international cancer organizations [8–10], with a shift in focus to how EPC can best be achieved [11–13].

Several potential models of EPC have been described [12, 14]. Of these, the model that has received the greatest attention and endorsement, in particular, for cancer centers, is simultaneous care by specialized palliative care in an outpatient setting [13, 15, 16]. This model was used in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating the benefits of EPC and was also supported by the results of nonrandomized prospective and retrospective studies [17–19]. Although this model has been examined qualitatively by a review of the electronic medical records of patients receiving EPC [20] and by interviewing oncologists and palliative care physicians [21, 22], the opinions of patients and caregivers regarding this model of care have not been sought.

We completed a cluster RCT of an EPC intervention versus standard cancer care at a tertiary cancer center that demonstrated improved quality of life, satisfaction with care, and symptom control in the EPC group compared with standard care [7]. On completion of the trial, we invited patients and caregivers in the control and intervention groups to participate in qualitative interviews. The purpose of the present study was to investigate, from the perspective of the patients and caregivers, what the perceived role was of their oncologist (control and intervention groups) and of their palliative care physician (intervention group only). A secondary aim was to examine whether the perceived role of the oncologist differed between participants in the control and intervention groups.

Materials and Methods

Participant Selection and Study Procedures

Details of the cluster RCT trial have been previously published [7] and are summarized below. Eligible patients were recruited from 24 medical oncology clinics at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, a comprehensive cancer center in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, from December 2006 to February 2011. Individual clinics were randomized either to the intervention group (early concurrent palliative care) or the control group (usual oncology care, with referral to palliative care at the discretion of the treating oncologist).

The eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of stage IV gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecological, or breast cancer, stage III or IV lung cancer, or locally advanced esophageal or pancreatic cancer; an estimated prognosis of 6 months to 2 years; and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0–2 [23] (the latter two criteria were determined by the patient’s medical oncologist). Patients were asked to identify their primary caregiver, who, in turn, was invited to participate in the study. Participants were excluded if they were younger than 18 years old, had scored poorly on a cognitive screening tool (patients only) [24], or lacked sufficient English proficiency to consent to the intervention or to complete the study questionnaires.

The intervention consisted of monthly visits to the ambulatory palliative care clinic for 4 months. The physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of the patient and any caregiver concerns were assessed at each visit. The participants received regular follow-up telephone calls from a palliative care nurse between visits and had access to the team both during the working week and out-of-hours, via the on-call physician [7].

Data Collection

After completion of the trial, the patients and caregivers were invited to participate in qualitative interviews. Purposive sampling was used with the aim of including a broad range of participants from the control and intervention groups with regard to age, gender, and responses to quality of life and satisfaction with care measures used in the trial [25–29]. Trained research personnel followed an interview guide to conduct semistructured, one-on-one interviews that ranged in length from 25 to 90 minutes. The interview guide included open-ended questions pertaining to participants’ perceptions of the respective roles played by their oncologist and their palliative care team. Field notes were recorded after each interview. The University Health Network Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Qualitative Analysis

The grounded theory method was used for data collection and analysis [30]. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed using a professional transcription service, before being verified by a research assistant. The NVivo software program, version 8, 2009, was used to facilitate management and analysis of qualitative data (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia, http://www.qsrinternational.com).

Data analysis was a dynamic process that began at the inception of data collection. Data were coded using an inductive, constant comparison method [30], whereby themes were generated through line-by-line coding and comparison within and between interviews. As new themes were identified, the interview guide was amended to verify the emergent themes [31]. At weekly team meetings, the themes were discussed and refined; this included identifying and discussing negative or divergent cases within each theme and integrating thematic categories around a core category [30, 32]. This iterative approach continued until theoretical saturation was reached [33].

Results

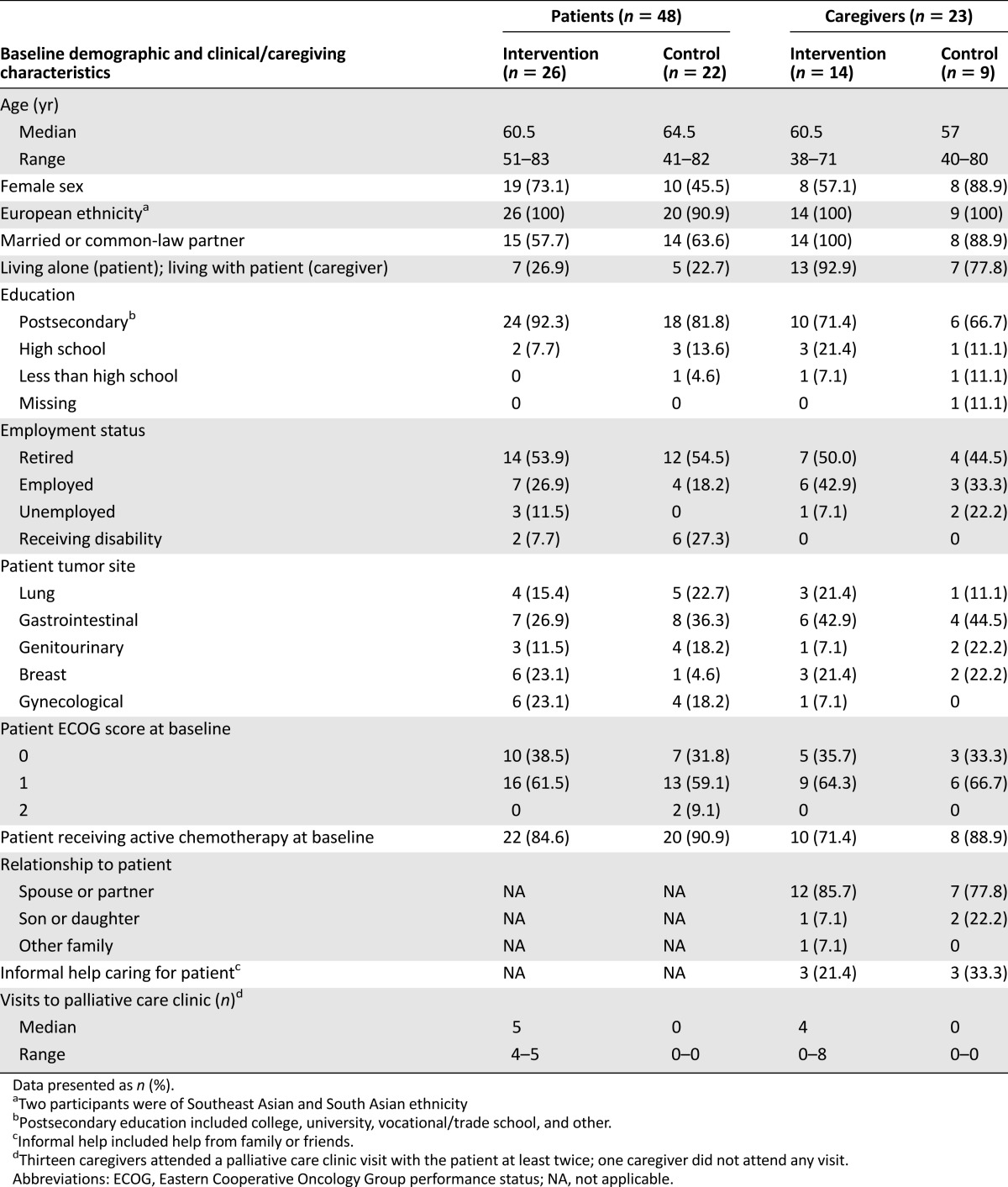

Of 85 patients and 50 caregivers who were approached, 48 patients (26 intervention; 22 control) and 23 caregivers (14 intervention; 9 control) consented to participate and completed interviews from July 2007 to March 2011. The main reasons for declining participation were feeling unwell or caring for an unwell patient (intervention group, 5 patients, 2 caregivers; control group, 1 patient, 3 caregivers); lack of time or interest (intervention group, 3 patients, 5 caregivers; control group, 14 patients, 5 caregivers); and palliative care content of the interview (control group, 4 patients, 3 caregivers). The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 71)

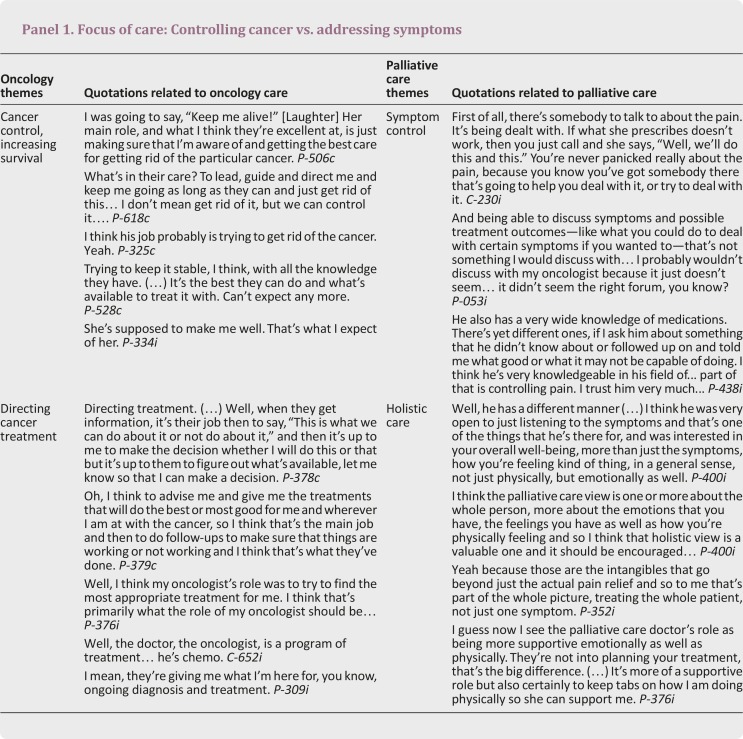

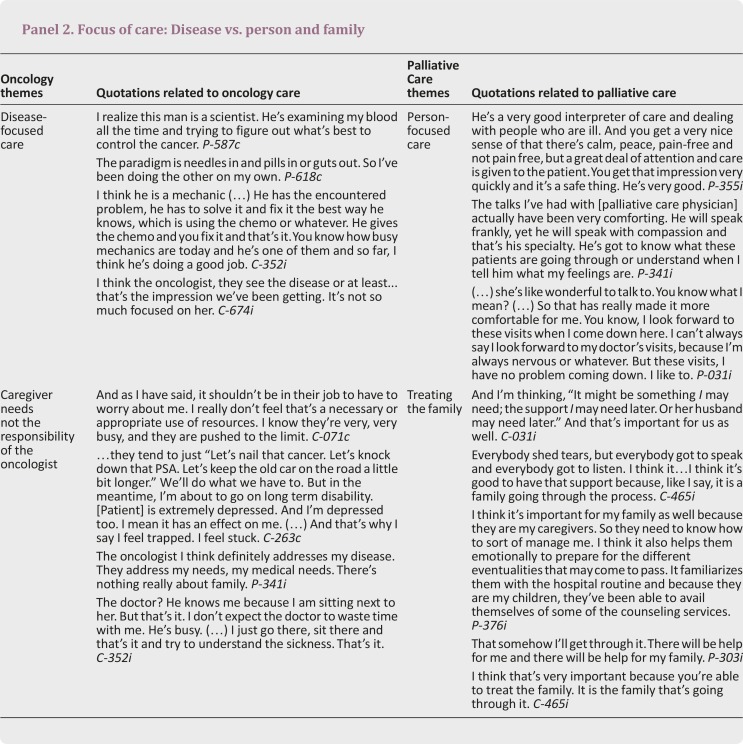

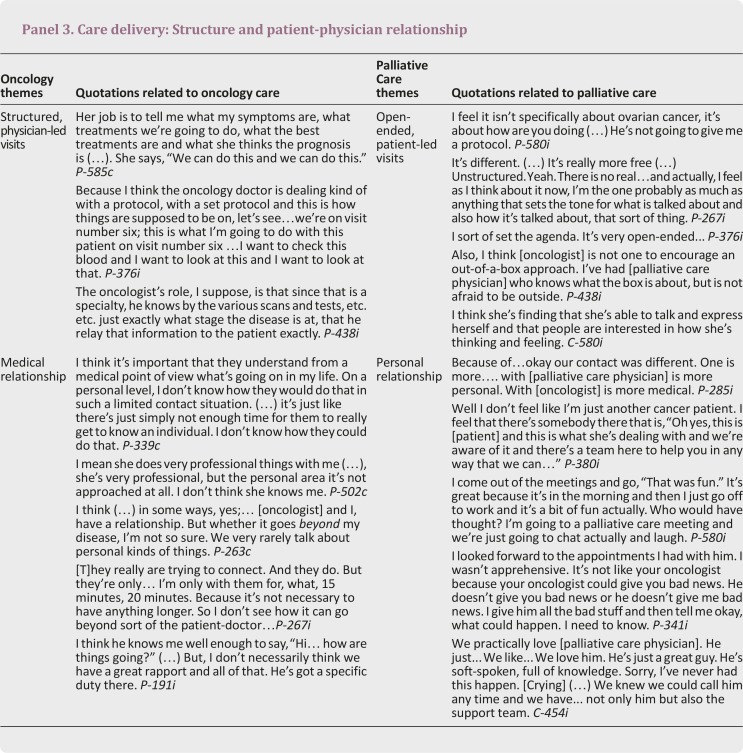

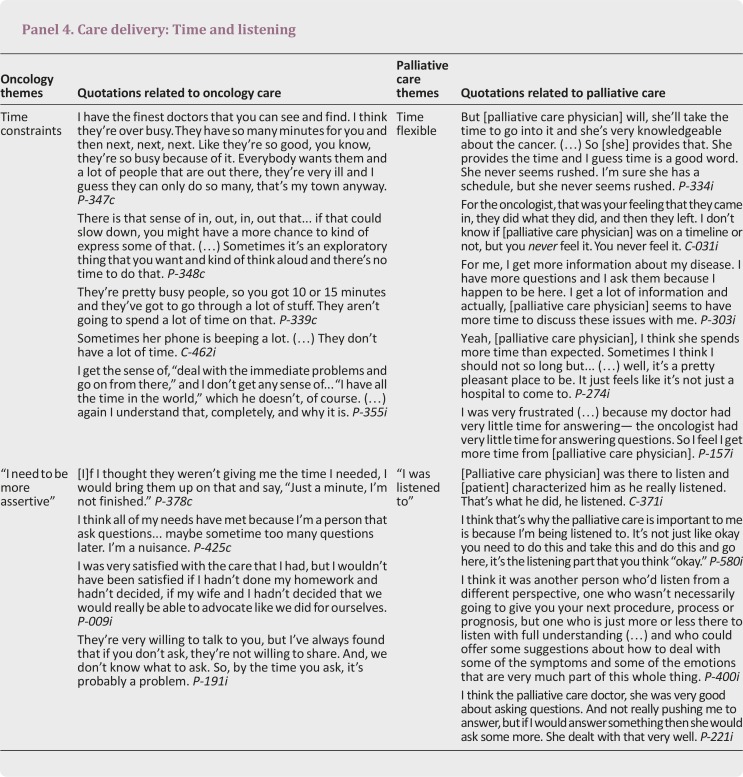

The emerging themes fell into three main categories, which related to the focus of care, the model of care delivery, and the manner in which the care from oncology and palliative care complemented each other to improve the patient and caregiver experience. Although some overlap was present in the roles, oncology care was perceived to be more cancer-centered and structured and palliative care to be more patient-centered and flexible. The themes within these categories and illustrative quotations are presented in Panels 1–5. No differences were found in the perceived role of the oncologist among those who participated in the palliative care intervention versus those in the control group.

Focus of Care: Treating the Cancer and the Person

Participants recognized a difference between the focus of their oncologist and that of the palliative care physician (Panels 1 and 2). Controlling the cancer was seen as an important responsibility: “Take care of the tumor” (P-543i [uppercase letter indicates patient (P) or caregiver (C), lowercase letter indicates intervention group (i) or control group (c); number indicates study unique identifier]). Directing anticancer treatment through a tailored approach was perceived to be the primary domain of the oncologist: “To get me the best possible care that’s out there. To keep me alive as long as possible” (P-341i). The oncologist was regarded as a “scientist” whose role was “to provide information about the cancer and its path” and “to give you the information about the option he feels is best, the path that’s best available to you” (C-325c). From the caregivers’ perspective, it was generally believed that attention to their particular needs was not the responsibility of the oncologist: “I don’t expect the doctor to waste time with me” (C-352i).

In contrast, most participants identified symptom control as the principal role of palliative care and, in particular, cited the palliative care physicians’ expertise in pain management: “Pain relief, real relief, great mental relief to know about it” (P-543i). They described the care in the palliative care clinic as “looking at a whole person” (P-334i), “being more supportive emotionally as well as physically” (P-376i), and providing support not only to the patient but also to the broader family. Visits to the clinic were described as “comforting,” with the palliative care physician being described as an “interpreter of care” or as a “doctor-therapist”: “He will speak frankly, yet he will speak with compassion, and that’s his specialty” (P-341i).

Care Delivery: Structure and Flexibility

Oncology clinics were described as following a predictable, structured pattern based on the particular management protocol or stage of treatment: “What do the blood tests show, what does the liver scan show, what do we have to do now and so on” (P-352i) (Panel 3). In contrast, participants described the palliative care clinic as being less formally structured and often directed by the individual concerns of the patient or their family member on the day of the visit, affording them a greater level of control: “I’m the one probably as much as anything that sets the tone for what is talked about and also how it’s talked about…” (P-267i).

Similarly, participants commented on a contrast in the dynamic of their relationship with the oncologist compared with their relationship with the palliative care physician (Panel 3). With the oncologist, a more traditional “medical” physician-patient relationship was described, whereas the relationship between participants and their palliative care physician was seen as “more personal.” Some participants reported feeling less apprehensive attending their palliative care appointment than when they saw their oncologist, as they were unlikely to be confronted with upsetting information relating to their latest scan results or blood work: “It’s not like your oncologist because your oncologist could give you bad news” (P-341i).

Time constraints within oncology clinics were a recurrent theme: “They’re pretty busy people, so you got 10 or 15 minutes and they’ve got to go through a lot of stuff” (P-339c) (Panel 4). Many participants expressed the need for assertiveness and self-advocacy to maximize their interactions with their oncologist: “…just to make sure that if I have a question that especially is important to me at that particular visit to make sure that I do ask it and not just let it go” (P-376i). This contrasted with the longer, more flexible consultations in the palliative care clinic, where interactions were less rushed. Participants reported an environment in which their questions were encouraged and their concerns were heard: “I was listened to” (P-380i).

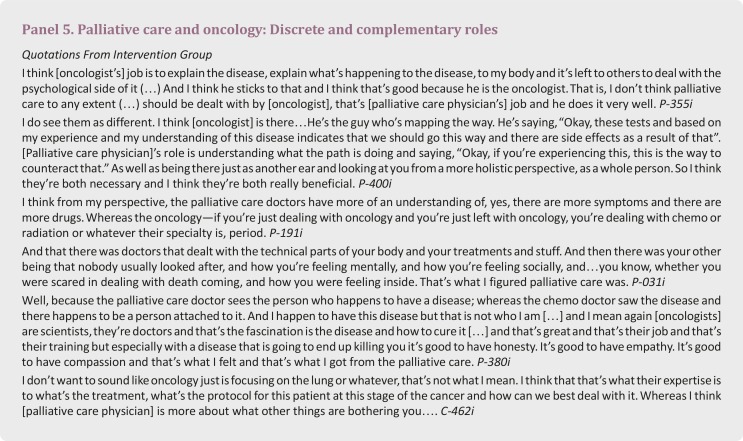

Palliative Care and Oncology: Discrete and Complementary Roles

Participants in the intervention group were able to articulate clearly the discrete and complementary roles of their oncologist and their palliative care physician (Panel 5). They described how having access to palliative care for symptom management and psychosocial support meant that their oncologist could focus on disease-specific issues and cancer treatment, with each specialty focusing on its area of expertise: “I guess that’s where I see [oncologist] being in charge of the cancer and [palliative care physician] assisting with the symptoms and the fallout” (C-400i). Rather than one being valued over the other, both were perceived to play a pivotal role in cancer care: “So I think they’re both necessary and I think they’re both really beneficial” (P-400i). Participants perceived that concurrent palliative care alongside oncology made their overall health care experiences more satisfactory and holistic:

Aside from all the things that I think the palliative care and symptom control team have done that made it a better experience for [patient] and me, I think just the simple fact that there’s another specialty that’s being brought to bear and to not only have the specialty of the oncology people and having confidence in them, you get added confidence in your total (…) in the way that [the hospital] is looking after the person as a whole, not just treating the cancer but the person as a whole, the patient as a whole. (C-371i)

Discussion

In the present qualitative study, patients and caregivers who participated in a trial of EPC provided consistent accounts of the roles of their oncologists and their palliative care physicians in their care. Participants in both trial groups described the role of their oncologists as being rooted in devising a tailored, protocoled, cancer treatment plan with structured follow-up and monitoring. Those in the intervention group described the role of palliative care physicians as providing more holistic, less structured, symptom-based assessments in an unrushed atmosphere that allowed a more detailed exploration of personal and family concerns. The roles of oncology and palliative care were perceived to be discrete and complementary, with both contributing to comprehensive care for the patient and family.

These accounts lend support to a model of integrating palliative care into oncology care by early intervention in a specialized clinic setting. Although research in this area is limited, this integrated care model is one that has been recommended for cancer centers in recent reviews [16]. Other potential models include the “solo practice model,” in which oncologists assume all care from diagnosis to death, and the “congress practice model,” referring to multiple consultants who specialize in various symptom and psychosocial concerns [15, 34]. The solo practice model is limited by time constraints, variable interest in and comfort with discussing palliative and end-of-life care [35–37], and the lack of specialized training in palliative medicine [16]. This model also risks higher rates of burnout among oncologists, especially those who identify their role as rooted mainly in the biomedical realm [35]. The congress model has the disadvantage of necessitating the coordination of a myriad of appointments for individual symptoms, psychosocial concerns, and existential issues [15, 34]. The integrated care model, described in the present study, allows timely, efficient, and coordinated management of multiple physical, psychosocial, and existential needs by an interdisciplinary team [16].

The endorsement of an integrated model of care by patients and caregivers is consistent with qualitative accounts of oncologists and palliative care physicians. In a qualitative study, oncologists who had been exposed to an EPC model described benefits of such a model similar to those described in the present study, including access to expertise in symptom management and the additional time that palliative care physicians could devote to complex psychosocial issues and advance care planning [21]. In addition, they identified personal benefits in terms of sharing the care of complex patients and assisting in challenging conversations around transitions in care or prognosis. In another study, palliative care physicians described that they provided EPC by managing symptoms, engaging patients in emotional work, and assuming a mediating role between the oncologist and the patient [22]. Our study provides the crucial perspective of patients and their caregivers who did or did not receive an EPC intervention. Although participants in both trial arms were pleased with their care, the oncologist’s role was described as providing excellent cancer treatment, while the palliative care physician addressed broader symptom, psychosocial, and family-related concerns. These concerns could not be addressed as readily within the time-pressured, biomedically centered model of the oncology clinic.

Barriers exist to implementing an integrated care model for delivery of EPC. Although access to palliative care services has increased markedly over the past decade, these tend to be focused on providing care for inpatients, with variable access to outpatient palliative care clinics [3, 38, 39]. In a recent survey, palliative care clinics were available at 59% of National Cancer Institute (NCI) centers and 22% of non-NCI centers [38]. Even at centers with access to such clinics, referrals tend to occur late in the disease process [40], although oncologists with palliative care training tend to refer earlier in the course of illness [3]. One reason for late referrals is the faulty perception by those providing and receiving cancer care that palliative care is synonymous with “end-of-life” care [41–44]. This has led some services to change their name to “supportive care” [41] and has galvanized a broader interest in the education of both providers and the public about palliative care [45]. The lack of an adequate workforce of trained specialists in palliative care is also a limitation [42], although specialist training programs for palliative care are available in an increasing number of countries [46, 47].

Our study had a number of strengths. The study was nested in an RCT, allowing us to obtain the accounts and opinions of those who did or did not receive treatment from palliative care. Incorporating qualitative research methods into RCTs is rarely performed but increasingly recommended [48]. The relatively large qualitative sample, range of tumor sites and use of purposeful sampling methods allowed inclusion of a broad range of experiences. The limitations of the study included recruitment from a single tertiary cancer center with a well-established ambulatory palliative care program; this might not reflect the practices or experiences elsewhere. Also, only participants who had completed the trial were recruited into the qualitative study; those who had withdrawn early might have had differing views. Most participants were highly educated and of European backgrounds and might not reflect the experiences of other, more diverse demographic groups. The study was also limited to describing the perceived roles of oncologists and palliative care physicians; further research is needed to describe patient perceptions of the roles of other health care providers.

Conclusion

Patients and caregivers in the present study perceived distinct and complementary roles for oncology and palliative care, supporting an integrated care model for EPC. Further studies are needed to assess the role of family physicians in providing palliative care, to assess the effects of educational interventions for oncologists in palliative care, and to assess whether this integrated care model could be adapted to community hospitals and noncancer settings.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and family caregivers who participated in this study. We thank the medical oncologists who referred patients to the study and the clinical and administrative staff of the palliative care team at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. Special thanks to Debika Burman and Nanor Kevork (Department of Supportive Care, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre) for their assistance with preparation of study materials, participant recruitment, conduct and analysis of qualitative interviews, and data entry and preparation. This research was funded by the Canadian Cancer Society (Grants 017257 and 020509, C.Z.), the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation Vera Frantisak Fund, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. C.Z. is supported by the Rose Chair in Supportive Care, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. The views expressed in the study do not necessarily represent those of the sponsors, and the sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Camilla Zimmermann

Provision of study material or patients: Natasha Leighl, Monika Krzyzanowska

Collection and/or assembly of data: Breffni Hannon, Nadia Swami, Ashley Pope, Camilla Zimmermann

Data analysis and interpretation: Breffni Hannon, Nadia Swami, Ashley Pope, Gary Rodin, Camilla Zimmermann

Manuscript writing: Breffni Hannon, Nadia Swami, Natasha Leighl, Gary Rodin, Monika Krzyzanowska, Camilla Zimmermann

Final approval of manuscript: Breffni Hannon, Nadia Swami, Ashley Pope, Natasha Leighl, Gary Rodin, Monika Krzyzanowska, Camilla Zimmermann

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Whitmer KM, Pruemer JM, Nahleh ZA, et al. Symptom management needs of oncology outpatients. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:628–630. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beernaert K, Deliens L, Vleminck A, et al. Is there a need for early palliative care in patients with life-limiting illnesses? Interview study with patients about experienced care needs from diagnosis onward. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1049909115577352. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, et al. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4380–4386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charalambous H, Pallis A, Hasan B, et al. Attitudes and referral patterns of lung cancer specialists in Europe to specialized palliative care (SPC) and the practice of early palliative care (EPC) BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherny N, Catane R, Schrijvers D, et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Program for the integration of oncology and palliative care: A 5-year review of the designated centers’ incentive program. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:362–369. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Early palliative care: Moving from “why” to “how.”. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:168738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaertner J, Weingärtner V, Wolf J, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: How to make it work? Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:342–352. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283622c5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin J, Temel J. Integrating palliative care: When and how? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:344–349. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283620e76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruera E, Yennurajalingam S. Palliative care in advanced cancer patients: How and when? The Oncologist. 2012;17:267–273. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013–4017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:159–171. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Follwell M, Burman D, Le LW, et al. Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206–213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rugno FC, Paiva BS, Paiva CE. Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:283–290. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Oncologists’ perspectives on concurrent palliative care in a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11:415–423. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1244–1248. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, Jr, et al. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: Development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1026407010614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, et al. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: Measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3182–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kristjanson LJ. Validity and reliability testing of the FAMCARE scale: Measuring family satisfaction with advanced cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90066-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Choosing Interviewees and Judging What They Say: More Issues in Design for Qualitative Research. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. pp. 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. Assembling the parts: Structuring a qualitative interview; pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. Validity; pp. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui D, Kim YJ, Park JC, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. The Oncologist. 2015;20:77–83. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson VA, Mack J, Matsuyama R, et al. A qualitative study of oncologists’ approaches to end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:893–906. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeil TA, Laryionava K, Reiter-Theil S, et al. What keeps oncologists from addressing palliative care early on with incurable cancer patients? An active stance seems key. The Oncologist. 2015;20:56–61. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granek L, Krzyzanowska MK, Tozer R, et al. Oncologists’ strategies and barriers to effective communication about the end of life. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:e129–e135. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui D, Bansal S, Strasser F, et al. Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: An international consensus. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1953–1959. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2012;17:1574–1580. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:224–239. doi: 10.1177/0269216315606645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e37–e44. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ. 2016 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151171. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Partridge AH, Seah DSE, King T, et al. Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: The time is now. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3330–3336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolognesi D, Centeno C, Biasco G. Specialisation in palliative medicine for physicians in Europe 2014. A supplement of the EAPC atlas of palliative care in Europe. Milan: EAPC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark D. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. International progress in creating palliative medicine as a specialized discipline; pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:99–121. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]