Abstract

Background

The endothelial glycocalyx is an important component of the vascular permeability barrier, forming a scaffold that allows serum proteins to create a gel-like layer on the endothelial surface, and transmitting mechanosensing and mechanotransduction information that influences permeability. During acute inflammation the glycocalyx is degraded, changing how it interacts with serum proteins and colloids used during resuscitation and altering its barrier properties and biomechanical characteristics. We quantified changes in the biomechanical properties of lung endothelial glycocalyx during control conditions and after degradation by hyaluronidase using biophysical techniques that can probe mechanics at: 1) the aqueous/glycocalyx interface and 2) inside the glycocalyx. Our goal was to discern the location-specific effects of albumin and hydroxyethyl starch (HES) on glycocalyx function.

Methods

The effects of albumin and HES on the mechanical properties of bovine lung endothelial glycocalyx were studied using a combination of atomic force microscopy (AFM) and reflectance interference contrast microscopy (RICM). Logistic regression was used to determine the odds ratios for comparing the effects of varying concentrations of albumin and HES on the glycocalyx with and without hyaluronidase (HA’ase).

Results

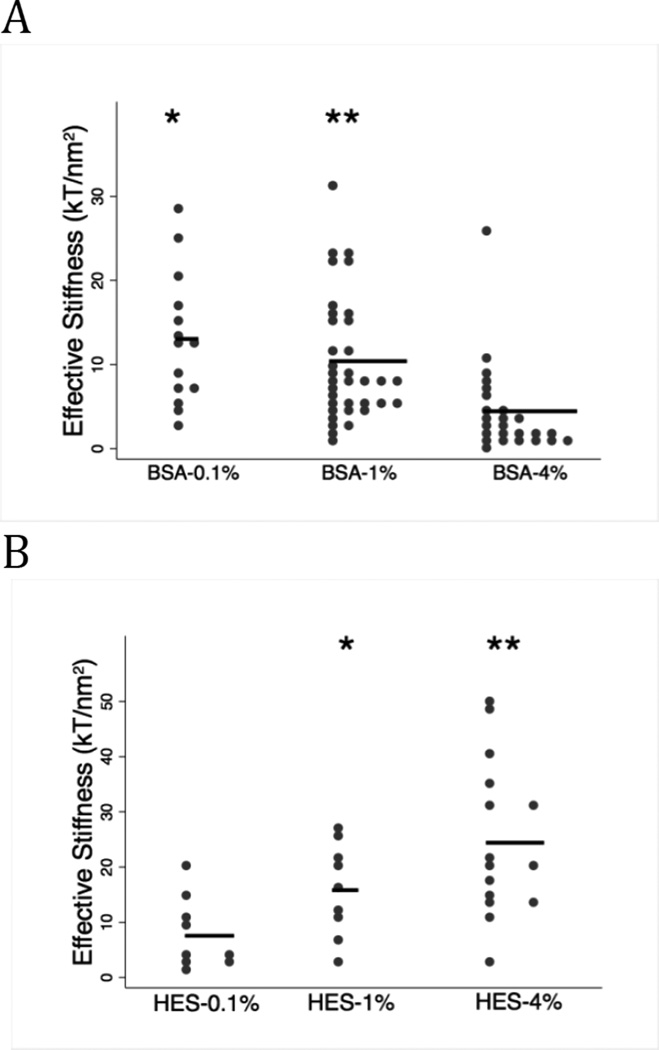

AFM measurements demonstrated that both 0.1 % and 4% albumin increased the thickness and reduced the stiffness of glycocalyx when compared with 1% albumin. The effect of HES on glycocalyx thickness was similar to albumin, with thickness increasing significantly between 0.1% and 1% HES and a trend towards a softer glycocalyx at 4% HES. RICM revealed a concentration-dependent softening of the glycocalyx in the presence of albumin but a concentration dependent increase in stiffness with HES. After glycocalyx degradation with HA’ase, stiffness was increased only at 4% albumin and 1% HES.

Conclusions

Albumin and HES induced markedly different effects on glycocalyx mechanics and had notably different effects after glycocalyx degradation by hyaluronidase. We conclude that HES is not comparable to albumin for studies of vascular permeability and glycocalyx-dependent signaling. Characterizing the molecular and biomechanical effects of resuscitation colloids on the glycocalyx should clarify their indicated uses and permit a better understanding of how HES and albumin affect vascular function.

Introduction

The endothelial glycocalyx is believed to play an important role in vascular permeability by functioning as a passive molecular filter overlying the endothelial cell-cell junction[1–3] and acting as an signaling platform that regulates barrier function. The glycocalyx generates a passive permeability barrier by creating a scaffolding upon which serum proteins absorb and form a gel-like layer on the vascular wall. Historically, this layer has been referred to as “the immobile plasma layer”, and limits the flux of water and plasma proteins into the intercellular junction. The combination of the immobile plasma layer and the glycocalyx scaffold has been termed the endothelial surface layer (ESL) by Pries[3] (Figure 1). Components of the glycocalyx function as mechanosensor(s) and mechanotransducer(s) that respond to pressure[1; 4] and shear stress[5–7] and activate downstream signaling pathways associated with increased vascular permeability and tissue edema[8; 9].

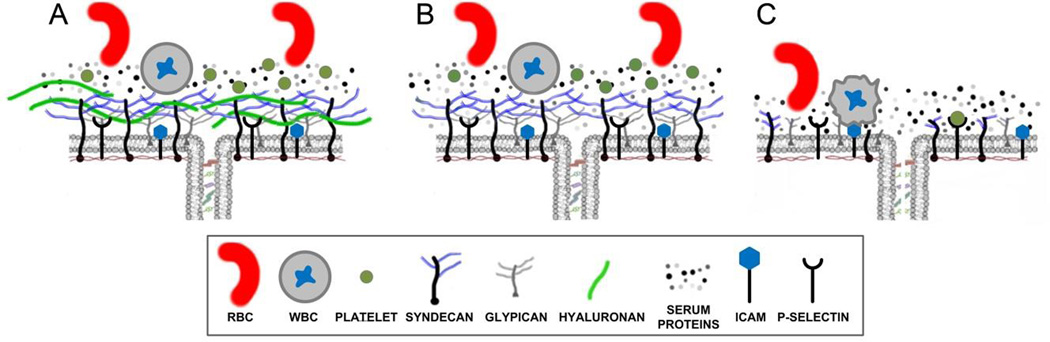

Figure 1. Structure of the Glycocalyx.

A) Intact glycocalyx demonstrating barrier properties of the glycocalyx in limiting penetration of serum proteins to the junction preventing the interaction of blood cells with cell surface receptors. B) Removal of HA increases penetration of glycocalyx by serum proteins. C) Complete degradation of glycocalyx during intense inflammation eliminates barrier function and allows platelets and WBC to interact with their cell surface receptors, thus propagating the inflammatory response.

Changes in plasma protein concentration or colloid composition may affect endothelial function and permeability[2] through passive barrier properties of the glycocalyx and by modulating mechanosensing and mechanotransduction[7]. Because the composition of plasma expanders such as albumin and hydroxyethyl starch (HES) may affect endothelial cell responsiveness to hemodynamic changes[10], the choice of resuscitation colloid can influence physiological NO production and vascular reactivity. We have previously reported that NO release evoked by acutely increased hydrostatic pressure[1] is responsible for changes in endothelial permeability in the isolated perfused lung preparation[4]. This difference between albumin and hydroxyethyl starches on glycocalyx-dependent NO production is dependent on their molecular interactions with the glycocalyx and subsequent effect(s) on biomechanical properties[10–12] that influence mechano-sensitive signaling.

The glycocalyx is degraded during the acute inflammation of surgery[13–15], trauma[16; 17], respiratory failure[18], myocardial infarction/cardiac arrest[19; 20], sepsis[21] and HELLP syndrome[22]. This degradation is mediated via the actions of plasma proteases and endothelial metalloproteases[23]. The extent of glycocalyx degradation and the loss of specific constituents influences how resuscitation colloids bind to the endothelial surface,[12; 24; 25] and the ability of specific colloids to maintain or restore barrier characteristics[12; 26] (Figure 1B,C). The debate regarding crystalloid vs. colloids and what type of colloid is more clinically appropriate cannot be mechanistically addressed until we have a more complete understanding of how specific colloids influence the biological functions of the glycocalyx. The observation that resuscitation colloids have oncotic-independent effects via their binding to the glycocalyx suggests that better understanding the functional attributes of colloids on glycocalyx-dependent processes may better inform clinical choices[27].

In the present study, we started with the hypothesis that the acute inflammatory response provoked by surgery and associated tissue trauma will degrade the endothelial glycocalyx and compromise how natural serum proteins like albumin or resuscitation colloids, like HES interact with the intact glycocalyx and cell surface remnants that persist after degradation. To mimic the effect of glycocalyx degradation on albumin and HES interactions with glycocalyx remnants, we re-assessed the effects of clinically relevant concentrations of albumin vs. hydroxyethyl starches on glycocalyx biomechanics after degradation with hyaluronidase.

Our laboratories have established two complementary techniques to probe the micromechanics of the endothelial glycocalyx: 1) reflectance interference contrast microscopy (RICM) and 2) atomic force microscopy (AFM). Both techniques use a nano-scaled spherical probe to impart small loading forces onto the glycocalyx. The applied forces differ in these two techniques: due to very low loading forces, RICM probes the outer most region of the glycocalyx (< 10 nm indentation) while AFM applies increasing forces that indent progressively deeper into the glycocalyx, over a 50–700 nm range. These techniques were used independently to determine biomechanical parameters associated with the glycocalyx including effective stiffness of the outer most region of the glycocalyx, and a point-wise elastic modulus (E) as a function of indentation depth. The later function was fitted to a simple two-layer composite compliance model to find: a) the mean glycocalyx thickness, b) the elastic moduli of the glycocalyx and c) the mechanics of underlying cell structure.

Methods

Cell Culture

Bovine lung microvascular endothelial cells (BLMVEC; VEC Technologies; Rensselaer, NY; passage 5–13) were plated at a density of 1.25 × 105 cells/cm2 and grown to confluence on ethanol-washed, autoclaved, 25 mm round glass coverslips pretreated with 0.4% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 µg/cm2 fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich), for 1 hour each. Growth media was MCDB-131 Complete Medium (VEC Technologies) or a 50/50 mixture of this media with MCDB 131 Medium (Sigma, M8537) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 10% FBS, and 15 mM sodium bicarbonate at pH 7.4. BLMVEC monolayers were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until use on days 7–12[11].

Enzymatic Digestion of Hyaluronan

BLMVEC monolayers were incubated with 50 U/mL hyaluronidase (EC 4.2.2.1; hyaluronidase from Streptomyces hyalurolyticus, (Sigma) supplemented with 1% BSA and 25 mM HEPES at pH 7.4 for one hour prior to experiments in MCDB-131. Incubation was done at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Colloid Addition

Prior to experiments, monolayers were rinsed with un-supplemented MIII (1:3 mixture of MCDB-131 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES at pH 7.4 and Ringer’s Lactate (pH 7.4). Stiffness measurements were performed in MIII in the presence of 0.1%, 1%, or 4% weight volume (w/v) of either Fraction V bovine serum albumin (Proliant Biologicals; MW = 66.5 kDa) or high molecular weight hetastarch (HES) routinely used as a plasma expander (HEXTEND; weight average MW = 600 kDa, 0.75 degree of substitution).

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

The AFM experiments used to measure the elastic modulus, E, of BLMVECs have been previously described[28] (Figure 2A). An AFM cantilever was modified by attaching a borosilicate glass sphere, with a diameter of ~18 µm, which was then used to indent the glycocalyx and cell membrane. An increasing loading force, from 0 to 5–10 nN, was applied at a rate of 10 µm/s. Indentation locations were assigned based on the AFM topography map obtained at the end of the indentation experiments. Only cell-cell junction locations were selected for analysis. The AFM indentation data was analyzed point-wise to obtain the elastic modulus, E, as a function of the indentation depth, δ. The resulting E(δ) curves were analyzed using a two-layer composite compliance model to obtain the mean elastic moduli of the glycocalyx and the underlying cellular structures[28; 29]:

| Eq. 1 |

where E represent the elastic modulus of the glycocalyx (Eglycocalyx) or the cell (Ecell), respectively; the parameter α is a measure of mechanical interlayer interaction and δg is the thickness of the glycocalyx. For such analysis to be conclusive, the E(δ) curves must display a sigmoidal shape; in the absence of such shape, the glycocalyx modulus, Eglycocalyx, could be estimated from a point-wise modulus at 100 nm indentation depth, E100.

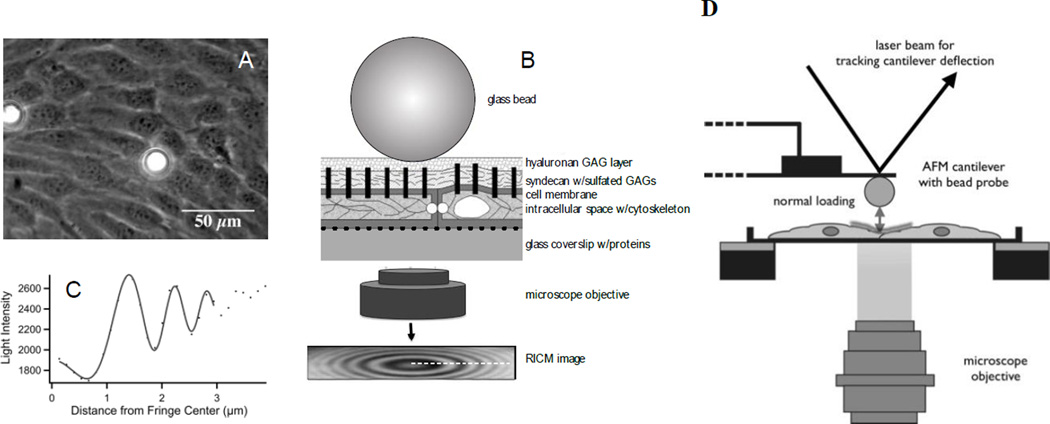

Figure 2. Biophysical Techniques to Measure Mechanics of the Glycocalyx.

A) Phase contrast image of 2 glass beads on a bovine lung microvascular endothelial cell (BLMVEC) monolayer to be used in reflectance interference contrast microscopy (RICM) measurements. B) Schematic of RICM bead probe placed on the top of BLMVEC glycocalyx (not drawn to scale). Monochromatic light reflected from bead and coverslip surface constructively interferes to create an interference pattern in the RICM image. C) Intensity profile of the interference pattern in the RICM image. This interference pattern profile changes when the distance between the bead and the coverslip fluctuates. GAG, glycosaminoglycan. The bead fluctuations are used to derive mechanical properties of the glycocalyx. D) Schematic of AFM bead probe indentation measurements of BLMVEC glycocalyx stiffness. Glass bead, glued to AFM cantilever, is gently pushed into the surface layer overlying a cell-cell junction to compress the BLMVEC glycocalyx. The upward deflection of the cantilever is tracked by a laser beam and position-sensitive diode and is converted into a loading force. The loading forces and resulting indentation depths are then used to compute the glycocalyx elastic modulus.

The effect of the colloid concentrations on glycocalyx modulus and thickness was assessed by subtracting the E(δ) data measured at a given albumin (or HES) concentration from the E(δ) data measured at a colloid concentration of 1%.

| Eq. 2 |

All data fitting was performed using IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR).

Reflectance Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM)

Effective stiffness of the glycocalyx was measured using RICM as previously described[11] (Figure 2B). RICM is an interferometric technique that measures the fluctuations of a glass sphere in the vertical position when placed on the surface of a confluent monolayer of BLMVECs. The glass sphere (18 µm diameter) serves as a force probe that exerts very small loads of approximately 50 pN and indents the glycocalyx several nanometers. The sphere-cell equilibrium is modeled as a particle at a potential energy minimum, where gravitational and restoring elastic forces balance each other[11; 30]. The vertical fluctuations follow the Boltzmann law[11; 30], so that the profile of the potential energy, U, around the minimum can be calculated as a function of the vertical position, h. The second derivative of U(h) thus provides a measure of effective stiffness for sphere-cell interactions[11]. The effective stiffness is then attributed to the glycocalyx, because loading forces are small and the bead itself is rigid compared with underlying structures like the cell membrane and sub-membranous cytoskeleton. For analysis of effective glycocalyx stiffness, only sphere locations from cell-cell junction were used. RICM is estimated to have a spatial resolution of approximately 300 nm[31] and a vertical resolution that is sub-nanometer[11].

Statistical Analyses

All references to sample size throughout the manuscript (Methods, Results, Figure Legend) refer to independent measurements made from a specific point within a confluent endothelial monolayer. For atomic force microscopy (AFM) this point is where the AFM cantilever was used to indent the endothelial glycocalyx. For reflectance interference microscopy (RICM) each sample represents an independent borosilicate bead placed on the cell surface (see Methods for greater detail) and used to measure glycocalyx mechanics. In most cases, all data for a specific group (e.g. albumin 1%, n=51) was obtained from 1–2 coverslips that contained a confluent monolayer of endothelial cells. The coverslips for each group were plated at the same time and all measurements were taken on the same day.

Statistical analyses of RICM data (Effective stiffness, kT/nm2 units) and AFM data (Elastic moduli, kPa units) were performed using STATA 13. We performed logistic regression with a binary dependent variable being the “group” to determine the odds ratios then compared the groups of all concentrations of albumin or HES with and without hyaluronidase during RICM and AFM treatment to each other, in all tested combinations. Differences were considered signifficant at p < 0.0167 after adjusting for family wise error rate from three sets of pair wise comparisons using Bonferroni correction. P-values and Bonferroni adjusted 98% confidence intervals corresponding to each comparison are reported in Table 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Comparison of the treatment groups for AFM data using logistic regression analysis.

| Group 1 vs. Group 2 (kPa) | P-value | 98% Confidence Interval (kPa) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% BSA (μ = 0.18; n = 37) | 0.1% BSA (μ = 0.13; n = 39) | 0.001 | (5.75E−15, 0.002) |

| 1% BSA (μ = 0.18; n = 37) | 4% BSA (μ = 0.14; n = 33) | 0.012 | (3.98E−10, 0.946) |

| 0.1% BSA (μ = 0.13; n = 39) | 4% BSA (μ = 0.14; n=33) | 0.303 | (0.002, 1.22E+07) |

| 0% HES (μ = 0.13; n = 39) | 1% HES (μ = 0.18; n = 20) | 0.011 | (0.114, 1.7) |

| 0% HES (μ = 0.13; n = 39) | 4% HES (μ = 0.16; n = 17) | 0.082 | (0.027, 5.53E+10) |

| 1% HES (μ = 0.18; n = 20) | 4% HES (μ = 0.16; n = 17) | 0.325 | (8.40E−08, 733.948) |

| 1% BSA (μ = 0.18; n = 49) | BSA-1%/HAase (μ = 0.21; n = 45) | 0.140 | (0.096, 35757.53) |

| 4% BSA (μ = 0.14; n = 33) | BSA-4%/HAase (μ = 0.22; n = 44) | 0.012 | (2.36 0.2.17E+09) |

| 1% HES (μ = 0.19; n = 39) | HES-1%/HAase (μ = 0.14; n = 41) | 0.001 | (2.19E−10, 0.017) |

| 4% HES (μ = 0.16; n = 17) | HES-4%/HAase (μ = 0.15; n = 36) | 0.910 | (5.98E−07, 443975.2) |

Group-wise comparison of AFM-derived elastic modulus (kPa) showing group condition (mean, sample size), Bonferroni-corrected p-value and Bonferroni-corrected confidence interval. Data presented as mean for AFM parameters obtained using the two-layer compliance model (see Methods) for 12 unique conditions. Based on Bonferroni correction, p<0.0167 was considered significant. AFM = atomic force microscopy; BSA = bovine serum albumin; HES = hydroxyethyl starch; HAase = hyaluronidase.

Table 4.

Comparison of treatment groups for RICM data using logistic regression analysis.

| Group 1 vs. Group 2 (kT/nm2) | P-value | 98% Confidence Interval (kT/nm2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% BSA (μ = 10.24; n = 35) | 0.1% BSA (μ = 12.94; n = 14) | 0.256 | (−0.865, 1.051) |

| 1% BSA (μ = 10.24; n = 35) | 4% BSA (μ = 3.38; n = 25) | 0.005 | (0.694, 0.966) |

| 0.1% BSA (μ = 12.94; n = 14) | 4% BSA (μ = 3.38; n = 25) | 0.005 | (0.676, 0.966) |

| 0.1% HES (μ = 7.88; n = 9) | 1% HES (μ = 15.99; n = 9) | 0.014 | (0.968, 1.394) |

| 0.1% HES (μ = 7.88; n = 9) | 4% HES (μ = 24.54; n = 15) | 0.004 | (0.388, 0.049) |

| 1% HES (μ = 15.99; n = 9) | 4% HES (μ = 24.54; n = 15) | 0.127 | (−0.965, 1.185) |

| 1% BSA (μ = 10.24; n = 35) | BSA-1%/HAase (μ = 15.41; n = 20) | 0.063 | (0.986, 1.139) |

| 4% BSA (μ = 3.38; n = 25) | BSA-4%/HAase (μ = 2.52; n = 23) | 0.170 | (−0.466, 0.120) |

| 4% HES (μ = 24.54; n = 15) | HES-4%/HAase (μ = 20.04; n = 9) | 0.468 | (−0.912, 1.049) |

Group-wise comparison of RICM-derived effective stiffness (kT/nm2) showing group condition (μ = mean, n = sample size), Bonferoni-corrected p-value and Bonferroni-corrected confidence interval. Data presented as mean for RICM parameters obtained using the two-layer compliance model (see Methods) for 8 unique groups. Based on Bonferroni correction, p<0.0167 was considered significant. RICM = reflectance interference contrast microscopy; BSA=bovine serum albumin; HES = hydroxyethyl starch; HAase = hyaluronidase.

Results

AFM Measurement of Glycocalyx Mechanics

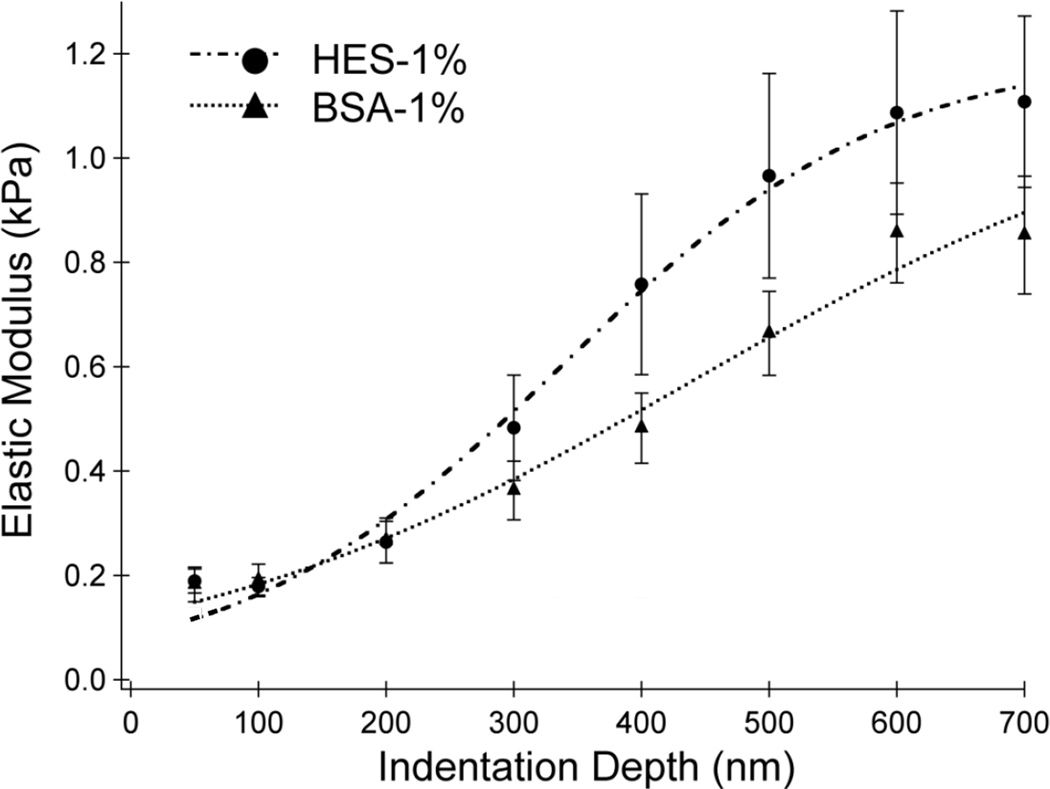

Figure 3 shows the elastic modulus, E(δ), measured using AFM on a confluent BLMVEC monolayer incubated in media containing 1% albumin or 1% HES. Each data set was fitted to a two-layer composite compliance model (Eq. 1); the modeled E(δ) curves are shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 3 and the fitted parameters are presented in Table 1. 1% HES produced a larger elastic modulus at deeper indentation depths compared to albumin - values suggesting that overall, HES made the glycocalyx stiffer. However, the two-layer composite compliance model predicted that the difference in stiffness between 1% albumin versus 1% HES was predominantly due to an increased glycocalyx thickness as the elastic moduli for both the glycocalyx E(δ) and whole cell (Ecell) were similar between the two colloids (Table 1 and 2). A consistent trend that was observed in AFM studies of differing colloid composition and concentrations was that a thicker glycocalyx was softer and a thinner glycocalyx was stiffer.

Figure 3. Elastic Moduli vs. Indentation Depth.

Mean elastic moduli at cell-cell junctions of BLMVEC monolayers as a function of indentation depth for samples with 1% HES (n = 20) and 1% BSA (n = 37) supplementation. Higher modulus values denote stiffer structures. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Table 1.

Two-layer composite compliance model parameters obtained for E(δ) data at 1% BSA or 1% HES concentrations. The goodness of each fit is measured by χ2 parameter shown.

| Parameter | 1% HES | 1% BSA |

|---|---|---|

| Eglycocalyx (kPa) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| Ecell (kPa) | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.23 |

| α | 2.46 | 2.59 |

| Glycocalyx Thickness, δg (nm) | 317 ± 38 | 532 ± 102 |

| χ2 | 0.0106 | 0.0097 |

Data presented as mean ± SD for AFM parameters obtained using the two-layer compliance model (see Methods) at 1% HES and 1% BSA. Goodness of fit for each parameter, χ2, was compared between colloid condition and χ2 <0.05 was considered significantly different. HES = hydroxyethyl starch; BSA = bovine serum albumin.

Table 2.

Two-layer composite compliance model parameters obtained from fitting Δαδ data shown in Figs 2 – 4 at three colloid concentrations. The goodness of each fit is measured by χ2 parameter shown.

| Parameter | 0.1 % BSA | 1% BSA | 4 % BSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eglycocalyx (kPa) | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.03 |

| Ecell (kPa) | 1.15 ± 0.40 | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 1.16 ± 0.23 |

| α | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.59 |

| Glycocalyx Thickness, δg (nm) | 1267 ± 68 | 532 ± 102 | 910 ± 49 |

| χ2 | 0.00003 | 0.0097 | 0.0122 |

| 0 % HES | 1% HES | 4 % HES | |

| Eglycocalyx (kPa) | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Ecell (kPa) | 1.20 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 1.23 ± 0.13 |

| α | 2.46 | 2.46 | 2.46 |

| Glycocalyx Thickness, δg (nm) | 618 ± 13 | 317 ± 38 | 410 ± 6 |

| χ2 | 0.0029 | 0.0106 | 0.0045 |

| 1% BSA | BSA-1 %/HAase | BSA-4%/HAase | |

| Eglycocalyx (kPa) | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| Ecell (kPa) | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 1.10 ± 0.18 | 1.10 ± 0.18 |

| α | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.59 |

| Glycocalyx Thickness, δg (nm) | 531 ± 102 | 450 ± 4 | 322 ± 4 |

| χ2 | 0.0097 | 0.0005 | 0.0032 |

| 1% HES | HES-1%/HAase | HES-4%/HAase | |

| Eglycocalyx (kPa) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.05 |

| Ecell (kPa) | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 1.21 ± 0.07 |

| α | 2.46 | 2.46 | 2.46 |

| Glycocalyx Thickness, δg (nm) | 317 ± 38 | 391 ± 13 | 378 ± 18 |

| χ2 | 0.0106 | 0.0037 | 0.0141 |

Data presented as mean ± SD for AFM parameters (left column) obtained using the two-layer compliance model (see Methods) for 10 unique conditions. Goodness of fit, χ2 was considered significantly different when χ2 <0.05. AFM = atomic force microscopy; BSA = bovine serum albumin; HES = hydroxyethyl starch; HAase = hyaluronidase.

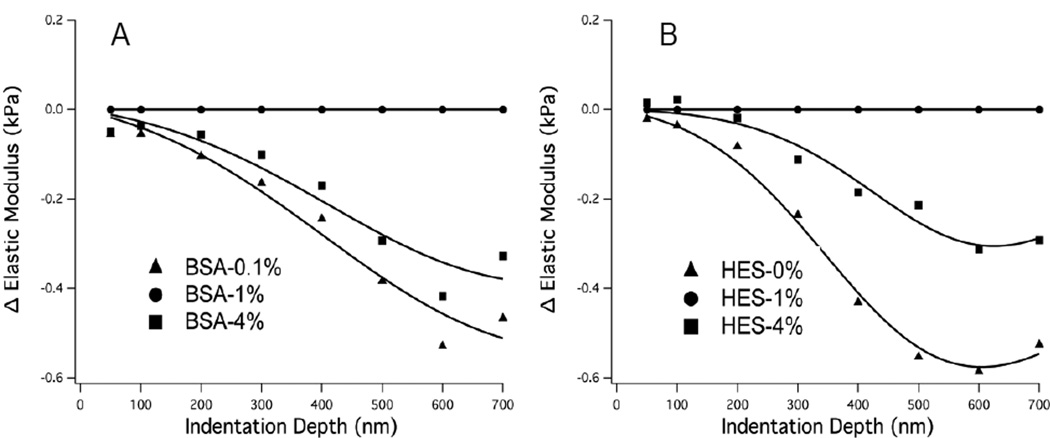

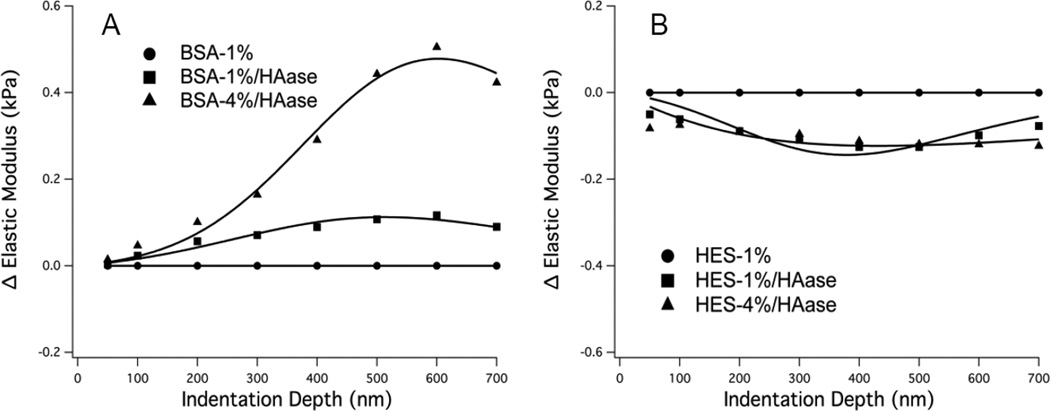

Figure 4 shows the mean E(δ) differences, i.e. ΔE(δ) = ΔE(θ) (at x%)−ΔE(δ) at (1%) where x% is the value at a specific colloid%, for all three concentrations of albumin and HES, while Figure 5 shows the results of ΔE(δ) after digestion with hyaluronidase. Table 2 presents the results of fitting the experimental data to the elastic modulus difference model defined by Eq. 1 and 2; the fitted parameter with the most significant change in response to different colloid concentrations was the glycocalyx thickness, δg. Although changes in fitted elastic modulus parameters were not as dramatic as the change in glycocalyx thickness, the changes in moduli with different colloid concentrations (Table 2) generally agreed with the elastic moduli measured at small indentation depth (e.g. 100 nm). Figure 4 indicates that the elastic modulus (primarily influenced by the thickness parameter) is softer and thicker at 0.1 vs. 4% BSA (panel A) and 0% vs. 4% HES (panel B) compared to 1% BSA and 1% HES, respectively. Treatment of cells with hyaluronidase completely altered the effects of albumin concentration on the glycocalyx stiffness, causing the glycocalyx to be thinner and stiffer at 0.1 and 4% BSA compared to 1% BSA (Figure 5A). Hyaluronidase treatment significantly diminished the effect of HES on E(δ) as both 0 and 4% HES resulted in a thicker and softer glycocalyx compared to 1% HES when Hyaluronidase was used (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Change in Elastic Moduli vs. Indentation Depth.

Differences in mean elastic moduli shown as a function of indentation depth obtained by subtracting the E(δ) data from the respective 1% experiment controls. A: BSA, 0.1% (n=39), 1% (n = 37), 4% (n = 33); B: HES, 0% (n=39), 1% (n = 20), 4% (n = 17). The modeled differences in ΔE(δ) are shown by the solid lines. The ΔE(δ) curves are negative indicating swelling of the glycocalyx compared to respective 1% experiment controls.

Figure 5. Change in Elastic Moduli vs. Indentation Depth.

Differences in mean elastic moduli after enzymatic digestion of glycocalyx hyaluronan (using 50 U/mL hyaluronidase) shown as a function of indentation depth obtained by subtracting the respective the E(δ) data from 1% experiment controls. A: BSA, 1% control (n = 35), 1% after HAase (n = 20) 4% after HAase (n = 23); B: HES, 1% control (n = 15), 1% after HAase (n = 42), 4% after HAase (n = 9). When the curves are higher than zero (panel A), the fitted thickness parameter decreases compared to respective 1% experiment controls, while the opposite is true when the curves are negative (panel B).

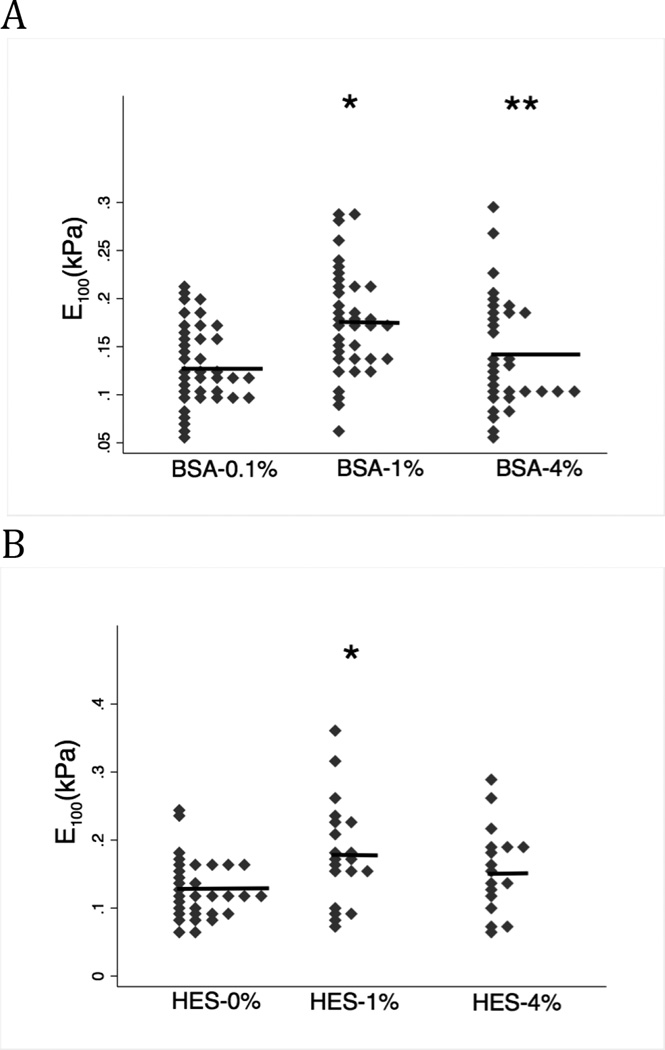

Using point-wise analysis (Methods, page 11), the elastic modulus (E) at an indentation depth of 100 nm was derived (E100) for 3 concentrations of albumin and HES (Figure 6). The E100 relationship for both albumin and HES over the range tested were very similar, demonstrating a significantly stiffer glycocalyx at 1% compared to 0.1 (p=0.001) and 4% (p=0.012) for albumin and for HES, significantly stiffer when comparing 1% vs. 0% (p=0.011); increasing HES from 1% to 4% had no further effect compared to HES 1% (p=0.325) (Figure 6 and Table 3 for additional parameters).

Figure 6. E100 measured in albumin or HES containing media.

Both colloids demonstrated a biphasic effects on glycocalyx stiffness; the mean E100 value is indicated by the horizontal lines. A: E100 was significantly greater (stiffer) in BSA-1% (n=37) vs. BSA-0.1% (n=39) (* p=0.001). Increasing BSA from 1% to 4% (n=33) resulted in smaller E100 (a softer glycocalyx); ** p-value=0.012). B: The relationship of E100 vs. HES-concentration. HES-1% (n=20) produced a larger E100 (stiffer glycocalyx) compared to HES-0% (n=39) (* p=0.011). E100 was reduced, but not significantly different, when HES concentration was increased from 1% to 4% (n=17) (p=0.325). In the intact glycocalyx, albumin and HES have similar concentration-dependent effects on the interior stiffness.

In the presence of hyaluronidase, albumin affected glycocalyx stiffness differently than HES. Treatment of endothelial cells with hyaluronidase had no effect on E100 in the presence of BSA-1% when compared to untreated cells in BSA-1% (Figure 7A, p=0.140). E100 was significantly increased by hyaluronidase treatment when the cells were in media containing BSA-4%, however (Figure 7A, p=0.012). Thus, removal of hyaluronan in the presence of BSA-4% made the glycocalyx stiffer.

Figure 7. E100 measured after hyaluronidase (HAase) treatment.

Mean E100 value is indicated by horizontal line. A. Hyaluronidase had no effect on E100 in the presences of BSA-1% (n=49) (BSA-1% vs. BSA-1%/HAase (n=45); p=0.140). However, HAase significantly increased E100 (e.g. stiffer glycocalyx) in the presence of BSA-4% (n=33) (BSA-4% vs. BSA-4% HAase (n=44); *p=0.012). B. HAase significantly reduced E100 (softer glycocalyx) in the presences of HES-1% (n=39) (HES-1% vs. HES-1%/HAase (n=41); *p=0.001). In the presences of HES = 4% (n=17), HAase had no significant effect on E100. (HES-4% vs. HES-4%/HAase (n=36); p=0.910). In summary, removal of hyaluronan from the glycocalyx has distinctly different effects on glycocalyx stiffness depending on the concentration of albumin or HES.

Figure 7B presents the effects of hyaluronidase on E100 in the presences of HES. Hyaluronidase significantly reduced E100, resulting in a softer glycocalyx, when cells were incubated in media containing HES-1% (p=0.001). Hyaluronidase had no effect on E100 in the presence of HES-4% (p=0.910).

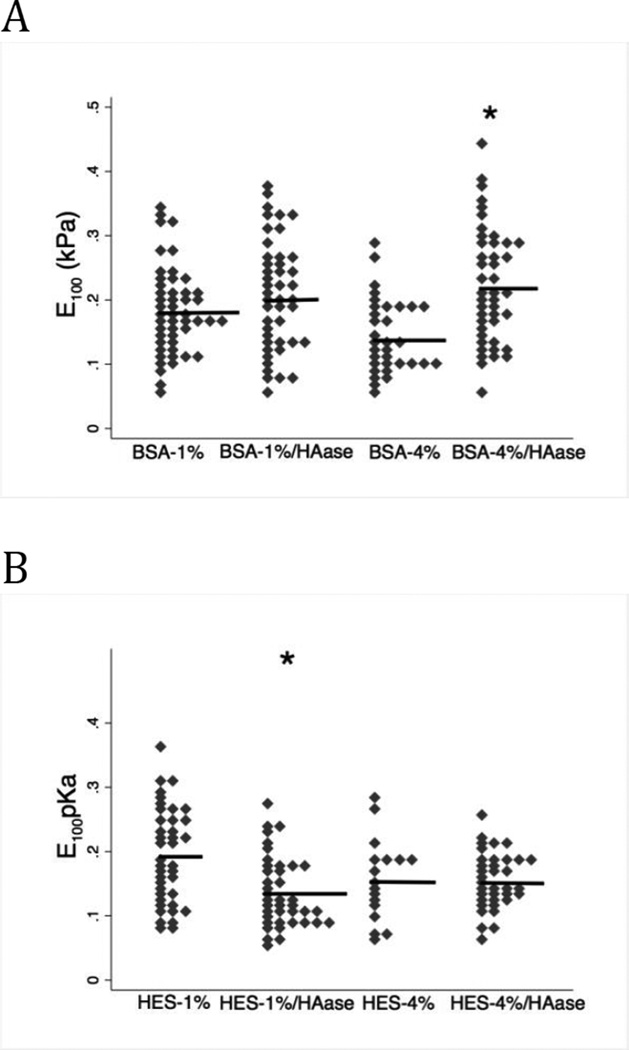

RICM: Mechanics at the Glycocalyx-Fluid Interface

The stiffness of the glycocalyx obtained from RICM experiments during incubation with albumin and HES are shown in Figure 8. Albumin induced a decrease in effective stiffness, resulting in a softer glycocalyx at 4% relative to 0.1% or 1% albumin (Figure 8A, p=0.005). The effective stiffness of BSA=0.1 and BSA 1% solutions did not differ. Conversely, HES produced a concentration dependent stiffening of the glycocalyx as evidenced by an increase in effective stiffness at both HES-1% (p=0.014) and HES-4% (p=0.004). (Figure 8B). Thus, albumin and HES have opposite effects on the stiffness of the outer most region of the glycocalyx (also see parameters in Table 4).

Figure 8. Effective stiffness of the outer most region of the glycocalyx.

A. Albumin induces a concentration-dependent softening of the glycocalyx (lower effective stiffness). The glycocalyx was significantly stiffer at BSA=0.1 (n=14) vs. 4% (n=25) indicated by (* p-value=0.005) and when comparing albumin concentrations of 1% (n=35) and 4% (** p-value=0.005). There was no difference in effective stiffness between albumin concentrations of 0.1 and 1%(p=0.256). B: HES resulted in a concentration-dependent stiffening of the glycocalyx with significant differences occurring between HES = 0.1% (n=9) vs. 1% (n=9) (* p-value =0.014) and between concentrations of 0.1% and 4% (n=23) (**p-value=0.004). Note that albumin and HES have opposite effects on glycocalyx stiffness at the glycocalyx-fluid interface.

Hyaluronidase had no effect on the effective stiffness parameter for albumin at either 1% (p=0.063) or 4% (p=0.170) (Figure 9A). Likewise, hyaluronidase had no effect on effective stiffness in the presences of HES-4% compared to untreated control cells (Figure 9B, p=0.468).

Figure 9. Comparison of the effective stiffness after hyaluronidase (haase) treatment.

The horizontal lines represent mean effective stiffness value. HAase had no effect on glycocalyx mechanics related to either albumin (panel A; p=0.063 and p=0.170) or HES concentrations (panel B ; p=0.468). These data suggest that hyaluronan is not a determinant of the effective stiffness at the glycocalyx-fluid interface.

Discussion

Overview of Results

The results of the present study demonstrate complex and anomalous effects of two different colloids (albumin vs. HES) on biomechanical properties of the lung endothelial glycocalyx. These findings provide unique insight into the disparate site-dependent effects of albumin and starch on the interior of the glycocalyx (assessed by AFM) and at the glycocalyx/fluid interface (assessed by RICM). These variable, site dependent effects of colloids may affect barrier function, mechanotransduction and vascular permeability differently in the intact glycocalyx, leading to divergent clinical properties. We found that during severe inflammatory states when clinicians are most likely to consider colloid use, the glycocalyx is compromised by proteases and other glycoprotein-degrading processes and under such conditions albumin has opposing effects vs. HES on biomechanical properties. Collectively, these results suggest that HES is not comparable to albumin when considering their biomechanical effects on the glycocalyx or on the interactions of each colloid with the glycocalyx, per se, and therefore the effects of colloids on glycocalyx-dependent processes that influence vascular physiology.

AFM

We have previously established two complementary techniques to evaluate the soft-layer mechanics of the glycocalyx[11; 32]: RICM and AFM each use an 18-µm diameter spherical probe to impart a loading force onto the glycocalyx. AFM measures mechanical properties with progressive indentation to approximately 700 nm into the glycocalyx while RICM measures equilibrium mechanics at much shallower (< 10 nm) depths and with very fast indentation rates. These techniques have allowed us to analyze glycocalyx mechanics and to quantify the mechanical effects of albumin and HES over a clinically relevant range. In addition, to simulate glycocalyx degradation as might occur during acute inflammation, we measured the mechanical effects of albumin and HES on the glycocalyx in the presence of hyaluronidase[11; 28].

In the present work, we determined the elastic modulus, E, of BLMVEC monolayers. As evident in Fig 3, albumin was associated with a softer glycocalyx (lower E) while HES resulted in an increase in glycocalyx stiffness at indentations depths from 300–700 nm. This effect is, in part, attributed to a reduction in the thickness of the glycocalyx in the presence of HES (Table 1) because the AFM loading forces are more effectively transmitted to the cell cytoskeleton. Using depolymerization of actin with cytochalasin D in BMLVEC, we have previously determined that at indentations depths deeper than 200–300 nm AFM measurements largely evaluate cytoskeleton mechanics. ased on those data, we conclude that the glycocalyx is approximately ten times softer than the underlying cellular structures. Given limitations in vertical AFM resolution, we assigned the glycocalyx modulus at the indentation depth of 100 nm (E100) as a measure of glycocalyx stiffness (Fig 6). For each colloid, the 1% concentration resulted in the stiffest mean elastic modulus and increasing or decreasing the albumin or HES concentration produced a softer glycocalyx.

Glycocalyx thickness (δg) was greater with albumin than with HES. In the presence of 1% albumin, δg = 532 ± 102 nm vs 317 ± 38 nm with 1% HES. These changes in the glycocalyx thickness were best revealed by analyzing ΔE(δ) curves as shown in Figs 4 and 5. A ΔE(δ) < 0 (Figs 4A,B) indicates glycocalyx thickening, and our data suggest that reducing albumin from 1% to 0.1% doubled glycocalyx thickness (at 0.1 %, δg = 1267 ± 68 nm vs. at 1 %, δg = 532 ± 102 nm; Table 2 and Fig 4A). The 2-fold increase in glycocalyx thickness is most likely caused by a reduced number of albumin-dependent crosslinks between hyaluronan and other glycocalyx components allowing the glycosaminoglycan chains to become unrestrained. Interestingly, an increase in albumin concentration from 1% to 4% also increased the glycocalyx thickness, albeit to a lesser extent than the change between 1.0% and at 0.1% (at 4 % δg = 910 ± 49 vs. at 1 % δg = 532 ± 102 nm; Table 2). This effect on glycocalyx thickness likely occurs as a result of excess albumin molecules within the glycocalyx and additional water and electrolytes that osmotically accompany albumin. The functional relationship that emerges between albumin concentration and glycocalyx thickness can be summarized as follows: at 1% albumin, the glycocalyx exists in a cross-linked or restrained state. When albumin concentration is reduced to 0.1%, the albumin dependent cross-linking is lost and the GAG chains become unrestrained, increasing glycocalyx thickness. When albumin concentration is increased to 4%, the excess albumin, water and electrolytes induces a swelling effect that also increases glycocalyx thickness. Thus, at both high and low albumin concentrations, the glycocalyx structure thickens, but by different mechanisms.

RICM Studies

RICM provided detailed assessment at the outer most regions of the glycocalyx, e.g. at the aqueous-fiber interface. Albumin induced a concentration-dependent softening of the glycocalyx over a 0.1 – 4% range. Conversely, HES increased the effective stiffness over a 0–4% range. These results differ from measurements made by AFM from the interior of the glycocalyx. The easiest explanation for these findings is that outer regions of the glycocalyx have different structural components and, therefore, interact differently with albumin and HES. However, these dichotomous findings might also have resulted from the difference in the speed with which loading forces were applied by AFM versus RICM. The AFM loading rate was quite low compared to the fast fluctuations in RICM. Because of these loading rate differences, the RICM-measured stiffness could have been influenced by viscous forces and related molecular rearrangements in a different way compared the AFM modulus. The potential role of loading rates and viscous forces thus adds an additional level of mechanical interactions that may influence endothelial signaling.

Are there other effects of albumin and HES that may explain these data?

It is possible that increasing the colloid oncotic pressure altered cell physiology sufficiently to also alter cell surface biomechanics. Chiang et al[33] observed that polyethylene glycol (PEG), a supposedly inert neutral polymer, had a biphasic effect on endothelial permeability and actin organization, increasing trans-endothelial electrical resistance over the range of 0–8%, but inducing barrier dysfunction above 8%. The increase in electrical resistance was associated with a reduction of actin stress fiber and an increase in peripheral actin. The effect of PEG on TEER and actin reorganization were complete in approximately 1 hour. In contrast, in our study, HES had a biphasic effect of glycocalyx stiffness over the range of 0–4%. Along with the increase in E100, which should exclude a cytoskeletal mechanism, this finding suggests that HES has direct effects on glycocalyx mechanics. However, in Figure 4, 4% HES also affected cell mechanics at depths below 300 nm which may indicate a cytoskeletal effect on the cytoskeleton. More work is needed to understand effects on colloids on cytoskeletal mechanics.

Glycocalyx Degradation: Effect on Biomechanics

During acute inflammation, glycocalyx constituents are shed by plasma proteases, neutrophil proteases, and endothelial membrane-associated metalloproteases[23; 34]. For example, activated neutrophils release proteases and have membrane-bound proteases that participate in neutrophil transmigration out of the vascular system. Major constituents of the glycocalyx, such as syndecan can be cleaved by several common proteases[35] plasma syndecan-1 has become a marker for the magnitude of vascular injury following trauma and hemorrhagic shock,[17; 19] and plasma glycosaminoglycans can be a signature for respiratory failure[18].

Based on our prior biophysical characterization of BLMVEC glycocalyx, we concluded that hyaluronan (HA) is a major structural constituent and, upon its removal from the glycocalyx, albumin dynamics within the glycocalyx were altered dramatically[24]. Likewise, others have demonstrated that HA removal significantly alters endothelial function[36; 37]. Therefore, we used hyaluronidase to selectively remove HA to mimic the degradation of the glycocalyx that may occur during acute inflammation. The removal of HA altered both the physical and mechanical properties of glycocalyx. The fitted thickness parameter (Table 2) indicated that hyaluronan caused a reduction in the glycocalyx thickness from 532 ± 102 nm (1% albumin) to 450 ± 4 nm and 322 ± 4 nm, for 1% and 4% albumin, respectively. Changes in the fitted glycocalyx modulus (Eglycocalyx, Table 2) also agreed very well with the RICM-measured effective stiffness of the outer most part of the glycocalyx layer (Fig 8B); both parameters decreased significantly with 4% albumin in the absence of hyaluronan (as compared with 1% albumin before or after removal of hyaluronan).

The changes in effective stiffness for 4% HES before and after removal of hyaluronan were statistically insignificant (Fig 9B) as were changes in the fitted δg parameter at these conditions (Fig 5B, C, Table 2). Overall, the mechanical parameters measured after hyaluronan removal of from the glycocalyx support our previous observation that the hyaluronan chains are a major component of the glycocalyx and are responsible for interactions with albumin[24]. These results also support the conclusion that hyaluronan chains are inert towards HES. Finally, our results support the findings of Zeng et al (2012)[25], who demonstrated that enzymatic removal of HA reduced the thickness of the cell-surface albumin layer on bovine aortic endothelial cells.

Limitations

The primary limitation to our study is the necessity to conduct these experiments using an in vitro model. This methodology is both a strength and weakness as RICM and AFM make precise measurements on a scale that is otherwise unattainable in vivo. However, controversy exists as to the composition and thickness of the glycocalyx of cultured cells versus its in vivo state. Measurements of the glycocalyx in vivo range from 0.4–5.0 µm[38–40] depending on the vascular bed and species studied. The controversy regarding the use of cell culture models is also driven by the type of endothelial cells chosen for comparison. For example, based upon electron microscopy and micro-velocitometry human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) have little, if any, glycocalyx[41]. This finding should not be surprising since HUVECs are derived from a conduit vessel where permeability of the umbilical vein has little physiological significance, limiting the value of HUVECs for studies on barrier properties.

We and others[6; 24; 25; 40; 42] have used a variety of methodologies including fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), rapid freezing/freeze substitution transmission electron microscopy and high resolution confocal microscopy to demonstrate that cultured endothelial cells from bovine lung (BLMVEC), bovine aorta (BAEC) and rat pad (RFPEC) possess a glycocalyx comparable in thickness to the in vivo state. Using rapid freezing/freeze substitution transmission electron microscopy, Tarbell and colleagues[40] reported a thickness of 11 um for BAEC glycocalyx and 5 um for rat fad pad endothelial cells. However, they used standard fixation techniques on these cells and observed a significant decrease in thickness of the glycocalyx. Thus, some forms of processing and fixation alter the measurable thickness. We used FCS, a biophysical modality that has sub-micron resolution, on live BLMVEC and measured a glycocalyx thickness of 1–3 microns. Using confocal microscopy and immuno-staining for heparan sulfates, we observed a cell-surface layer that was approximately 3.0 microns thick, providing good correlation with FCS. Tarbell and colleagues have published a series of papers[6; 25; 42] using high-resolution confocal microscopy of BAECs and RFPEC after immuno-staining for syndecan, glypican, heparan sulfate and albumin and consistently report a glycocalyx thickness of 1.5–3.0 µm.

The resolution of standard confocal microscopy is approximately 0.5–1.0 µ, depending upon the magnification and numerical aperture. In the current study, AFM and our two-layer composite model can derive changes of as little as 10–20 nm. The difference in glycocalyx thickness between albumin- vs. HES-treated cell was 200 nm, a difference that could not be measured with confocal imaging. This increased resolution highlights the value of biophysical techniques such as FCS (resolution 0.1 µm), RICM (resolution sub-nanometer) and AFM (resolution 10–20 nm) over other imaging modalities.

Clinical Relevance

The endothelial glycocalyx plays an important role in vascular barrier regulation[4], WBC adhesion[43], coagulation[44; 45], angiogenesis[46], and tissue repair[47]. Nearly all of these functions are relevant to perioperative clinicians. Moreover, understanding how resuscitation fluids like albumin and HES interact with the glycocalyx, and alter the structural and mechanical properties of the glycocalyx, has clinical implications in patient management and potentially in the development of novel resuscitation colloids[48; 49].

Safety concerns have been raised regarding the use of HES in specific clinical settings (e.g. sepsis), due to increased risk of acute kidney injury. Low MW 130/0.4 HES has largely replaced the use of high MW 600/0.7 HES but high MW HES is still available in the United States. Excluding sepsis and ICU patients, the risk associated with the use of any HES solutions, especially in healthy patients, has not been adequately addressed in randomized controlled clinical trials[50]. At the time we began these studies, high MW HES was in routine use and we selected it as a prototype colloid that was structurally distinct from albumin. Clearly, the shift to low MW HES (130/0.4) may alter the results of our study. However, we would not anticipate significant differences between 600 MW and 130 MW HES on the biomechanical measurements because both solutions are poly-dispersed, e.g. have a wide range of polymer sizes. Predictably, solubility and absorbability (larger macromolecules tend to be less soluble but adsorb better) may differ with HES MW but elastically the two HES fractions are similar. Overall, larger MW HES could adsorb more onto the glycocalyx, but produce a larger steric hindrance effect, whereas smaller MW starch solutions might have smaller adsorption, but allow better space usage (less steric hindrance). Ultimately, these two effects should compensate each other meaning that their mechanical behavior as measured by AFM and RICM should remain unchanged.

Clinical choices for resuscitation fluids include crystalloid (most commonly lactated ringer or normal saline), human albumin solutions or HES. Although we chose to focus on the effects of colloids on the biomechanical properties of the intact and compromised glycocalyx, the effects of crystalloids that are clinically used much more frequently are equally important. Although no direct studies on the effect of crystalloids on glycocalyx biomechanics exist a few points can be gleaned from our data. We assessed the effect of albumin over a concentration range from 0.1–4%; a plasma albumin concentration in this range would be considered hypo-proteinemic by clinical standards but could easily result from hemorrhagic shock where blood loss was replaced by a crystalloid solution. Reductions in plasma proteins on the interior mechanics of the glycocalyx are presented in Figures 6, demonstrating a biphasic effect on stiffness. In Figure 8, we observed a linear increase in glycocalyx stiffness as albumin concentration was reduced from 4% to 0.1%; these measurements were derived using RICM that measures the mechanics of the outmost structure of the glycocalyx. We can conclude that crystalloid resuscitation and the associated reduction in plasma protein would likely make the outer layer of the glycocalyx stiffer.

The ionic composition of resuscitation fluids, particularly hypertonic sodium solutions and even 0.9% saline will likely also affect the surface mechanics of the glycocalyx. Acute changes in extracellular sodium, above 135 mEq/l result in stiffening of endothelial cells and reduce nitric oxide production.[51] In these studies, however, the increase in cell stiffness occurred within minutes but the change in NO production occurred over days. It is not known if the acute change in cell stiffness is associated with rapid changes in NO production or glycocalyx shedding.

In addition to the composition of resuscitation fluid, the volume of fluid administered also impacts the integrity of the glycocalyx. Acute hypervolemic volume loading (VL) with 6% HES solution (130/0.4) increased plasma levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a protein that causes glycocalyx shedding[52; 53]. VL was associated with increased plasma syndecan-1, hyaluronan and heparan sulfate concentrations consistent with ANP induced glycocalyx breakdown. The mechanism(s) by which ANP promotes widespread breakdown of the glycocalyx remain unknown. In contrast, acute normovolemic hemodilution with 6% HES did not increase plasma ANP and was not associated with changes in plasma markers of glycocalyx breakdown..

Summary

Albumin and hetastarches differ in their effects on the biomechanical properties of the intact and partially degraded glycocalyx. These changes in colloid-dependent glycocalyx stiffness may have important implications in glycocalyx-dependent mechanotransduction and barrier function. It is clear that albumin and hetastarch are not comparable when used in studies of vascular function when factors other than oncotic pressure are operational. Whether a thicker or stiffer glycocalyx is better or worse is a complex question that cannot easily be answered given our current level of understanding. In terms of the glycocalyx as a passive barrier, thicker is considered better if other parameters (e.g. porosity, composition) have not changed. Glycocalyx stiffness is related to signaling sensitivity in a biphasic manner; if the glycocalyx is too soft it will be unable to transmit forces; if the glycocalyx is too stiff, it will not be stressed by the prevailing forces. In summary, understanding the molecular and biomechanical effects of resuscitation colloids should inform the practitioner towards their indicated uses and derive the best possible clinical effects that may enhance patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by: National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01#: 5R01HL085255)

Footnotes

Kathleen M. Job, Contribution: This author designed the studies, conducted the experiments, analyzed data and assisted in manuscript preparation.

Ryan O’Callaghan, Contribution: This author helped design the studies, conducted some of the experiments, and analyzed data.

Vladimir Hlady, Contribution: Planned experiments, assisted in data interpretation; assisted in manuscript preparation.

Alexandra Barabanova, Contribution: Assisted in data interpretation and analysis; assisted in manuscript preparation.

Randal O. Dull, Contribution: Planned experiments, assisted in data interpretation; assisted in manuscript preparation.

Attestation: Kathleen M. Job, Ph.D. approved the final manuscript. Kathleen M. Job Ph.D. attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in the manuscript.

Attestation: Ryan O’Callaghan, MS approved the final manuscript and he attests to integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Attestation: Vladimir Hlady, Ph.D. approved the final manuscript and he attest to the integrity of the original data and analysis reported in this manuscript.

Attestation: Alexandra Barabanova approved the final manuscript and attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Attestation: Randal Dull approved the final manuscript and attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Vladimir Hlady, Vladimir Hlady is Archival Author for all data.

Kathleen M. Job, Conflicts of Interest: None

Ryan O’Callaghan, Conflicts of Interest: None

Vladimir Hlady, Conflicts of Interest: None

Alexandra Barabanova, Conflicts of Interest: None

Randal O. Dull, Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Kathleen M. Job, Department of Bioengineering, University of Utah.

Ryan O’Callaghan, Department of Bioengineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Vladimir Hlady, Department of Bioengineering, University of Utah.

Alexandra Barabanova, Anesthesiology, University of Illinois Chicago.

Randal O. Dull, Anesthesiology, University of Illinois Chicago.

References

- 1.Dull RO, Mecham I, McJames S. Heparan Sulfates Mediate Pressure-Induced Increase in Lung Endothelial Hydraulic Conductivity Via Nitric Oxide/Reactive Oxygen Species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1452–L1458. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00376.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curry FE, Adamson RH. Endothelial Glycocalyx: Permeability Barrier and Mechanosensor. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:828–839. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0429-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. The Endothelial Surface Layer. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:653–666. doi: 10.1007/s004240000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dull RO, Cluff M, Kingston J, Hill D, Chen H, Hoehne S, Malleske DT, Kaur R. Lung Heparan Sulfates Modulate K(Fc) During Increased Vascular Pressure: Evidence for Glycocalyx-Mediated Mechanotransduction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L816–L828. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00080.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pahakis MY, Kosky JR, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. The Role of Endothelial Glycocalyx Components in Mechanotransduction of Fluid Shear Stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng Y, Tarbell JM. The Adaptive Remodeling of Endothelial Glycocalyx in Response to Fluid Shear Stress. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YS, Yaccino JA, Lakshminarayanan S, Frangos JA, Tarbell JM. Shear-Induced Increase in Hydraulic Conductivity in Endothelial Cells Is Mediated by a Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M-h, Harris NR, Tarbell JM. Regulation of Hydraulic Conductivity in Response to Sustained Changes in Pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2551–H2558. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00602.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M-h, Harris NR, Tarbell JM. Regulation of Capillary Hydraulic Conductivity in Response to an Acute Change in Shear. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2126–H2135. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01270.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob M, Rehm M, Loetsch M, Paul JO, Bruegger D, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. The Endothelial Glycocalyx Prefers Albumin for Evoking Shear Stress-Induced, Nitric Oxide-Mediated Coronary Dilatation. J Vasc Res. 2007;44:435–443. doi: 10.1159/000104871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Job KM, Dull RO, Hlady V. Use of Reflectance Interference Contrast Microscopy to Characterize the Endothelial Glycocalyx Stiffness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L1242–L1249. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00341.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehm M, Zahler S, Lötsch M, Welsch U, Conzen P, Jacob M, Becker BF. Endothelial Glycocalyx as an Additional Barrier Determining Extravasation of 6% Hydroxyethyl Starch or 5% Albumin Solutions in the Coronary Vascular Bed. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1211–1223. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200405000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehm M, Bruegger D, Christ F, Conzen P, Thiel M, Jacob M, Chappell D, Stoeckelhuber M, Welsch U, Reichart B, Peter K, Becker BF. Shedding of the Endothelial Glycocalyx in Patients Undergoing Major Vascular Surgery with Global and Regional Ischemia. Circulation. 2007;116:1896–1906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svennevig K, Hoel T, Thiara A, Kolset S, Castelheim A, Mollnes T, Brosstad F, Fosse E, Svennevig J. Syndecan-1 Plasma Levels During Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery with and without Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Perfusion. 2008;23:165–171. doi: 10.1177/0267659108098215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Golen RF, Reiniers MJ, Vrisekoop N, Zuurbier CJ, Olthof PB, van Rheenen J, Vangulik T, Parsons BJ, Heger M. The Mechanisms and Physiological Relevance of Glycocalyx Degradation in Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genet GF, Johansson PI, Meyer MA, Solbeck S, Sorensen AM, Larsen CF, Welling KL, Windelov NA, Rasmussen LS, Ostrowski SR. Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy: Standard Coagulation Tests, Biomarkers of Coagulopathy, and Endothelial Damage in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:301–306. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrowski SR, Johansson PI. Endothelial Glycocalyx Degradation Induces Endogenous Heparinization in Patients with Severe Injury and Early Traumatic Coagulopathy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:60–66. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825b5c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt EP, Li G, Li L, Fu L, Yang Y, Overdier KH, Douglas IS, Linhardt RJ. The Circulating Glycosaminoglycan Signature of Respiratory Failure in Critically Ill Adults. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:8194–8202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostrowski SR, Berg RM, Windelov NA, Meyer MA, Plovsing RR, Moller K, Johansson PI. Coagulopathy, Catecholamines, and Biomarkers of Endothelial Damage in Experimental Human Endotoxemia and in Patients with Severe Sepsis: A Prospective Study. J Crit Care. 2013;28:586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundmann S, Fink K, Rabadzhieva L, Bourgeois N, Schwab T, Moser M, Bode C, Busch HJ. Perturbation of the Endothelial Glycocalyx in Post Cardiac Arrest Syndrome. Resuscitation. 2012;83:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donati A, Damiani E, Domizi R, Romano R, Adrario E, Pelaia P, Ince C, Singer M. Alteration of the Sublingual Microvascular Glycocalyx in Critically Ill Patients. Microvasc Res. 2013;90:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann-Kiefer KF, Knabl J, Martinoff N, Schiessl B, Conzen P, Rehm M, Becker BF, Chappell D. Increased Serum Concentrations of Circulating Glycocalyx Components in Hellp Syndrome Compared to Healthy Pregnancy: An Observational Study. Reprod Sci. 2013;20:318–325. doi: 10.1177/1933719112453508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipowsky HH. The Endothelial Glycocalyx as a Barrier to Leukocyte Adhesion and Its Mediation by Extracellular Proteases. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:840–848. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens AP, Hlady V, Dull RO. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy Can Probe Albumin Dynamics inside Lung Endothelial Glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L328–L335. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng Y, Ebong EE, Fu BM, Tarbell JM. The Structural Stability of the Endothelial Glycocalyx after Enzymatic Removal of Glycosaminoglycans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob M, Bruegger D, Rehm M, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. Contrasting Effects of Colloid and Crystalloid Resuscitation Fluids on Cardiac Vascular Permeability. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1223–1231. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assaad S, Popescu W, Perrino A. Fluid Management in Thoracic Surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26:31–39. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32835c5cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Callaghan R, Job KM, Dull RO, Hlady V. Stiffness and Heterogeneity of the Pulmonary Endothelial Glycocalyx Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L353–L360. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00342.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doerner MF, Nix WD. A Method for Interpreting the Data from Depth-Sensing Indentation Instruments. Journal of Materials Research. 1986;1:601–609. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rädler J, Sackmann E. On the Measurement of Weak Repulsive and Frictional Colloidal Forces by Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy. Langmuir. 1992;8:848–853. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sackmann E. Supported Membranes: Scientific and Practical Applications. Science. 1996;271:43–48. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Callaghan R, Job KM, Dull RO, Hlady V. Stiffness and Heterogeneity of the Pulmonary Endothelial Glycocalyx Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L353–L360. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00342.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiang ET, Camp SM, Dudek SM, Brown ME, Usatyuk PV, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC, Garcia JG. Protective Effects of High-Molecular Weight Polyethylene Glycol (Peg) in Human Lung Endothelial Cell Barrier Regulation: Role of Actin Cytoskeletal Rearrangement. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipowsky HH, Sah R, Lescanic A. Relative Roles of Doxycycline and Cation Chelation in Endothelial Glycan Shedding and Adhesion of Leukocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H415–H422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00923.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manon-Jensen T, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR. Mapping of Matrix Metalloproteinase Cleavage Sites on Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 Ectodomains. FEBS J. 2013;280:2320–2331. doi: 10.1111/febs.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singleton PA, Mirzapoiazova T, Guo Y, Sammani S, Mambetsariev N, Lennon FE, Moreno-Vinasco L, Garcia JG. High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronan Is a Novel Inhibitor of Pulmonary Vascular Leakiness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L639–L651. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00405.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lennon FE, Singleton PA. Hyaluronan Regulation of Vascular Integrity. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:200–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith ML, Long DS, Damiano ER, Ley K. Near-Wall Micro-Piv Reveals a Hydrodynamically Relevant Endothelial Surface Layer in Venules in Vivo. Biophys J. 2003;85:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vink H, Duling BR. Capillary Endothelial Surface Layer Selectively Reduces Plasma Solute Distribution Volume. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H285–H289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebong EE, Macaluso FP, Spray DC, Tarbell JM. Imaging the Endothelial Glycocalyx in Vitro by Rapid Freezing/Freeze Substitution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1908–1915. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Potter DR, Damiano ER. The Hydrodynamically Relevant Endothelial Cell Glycocalyx Observed in Vivo Is Absent in Vitro. Circ Res. 2008;102:770–776. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng Y, Waters M, Andrews A, Honarmandi P, Ebong EE, Rizzo V, Tarbell JM. Fluid Shear Stress Induces the Clustering of Heparan Sulfate Via Mobility of Glypican-1 in Lipid Rafts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H811–H820. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00764.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Role of Glycocalyx in Leukocyte-Endothelial Cell Adhesion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1282–H1291. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00117.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierce A, Pittet JF. Inflammatory Response to Trauma: Implications for Coagulation and Resuscitation. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014;27:246–252. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres LN, Sondeen JL, Ji L, Dubick MA, Torres Filho I. Evaluation of Resuscitation Fluids on Endothelial Glycocalyx, Venular Blood Flow, and Coagulation Function after Hemorrhagic Shock in Rats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:759–766. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a92514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorsi B, Liu F, Ma X, Chico TJ, v A, Kramer KL, Bridges E, Monteiro R, Harris AL, Patient R, Stringer SE. The Heparan Sulfate Editing Enzyme Sulf1 Plays a Novel Role in Zebrafish Vegfa Mediated Arterial Venous Identity. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:77–91. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong M, Tuk B, Hekking IM, Vermeij M, Barritault D, van Neck JW. Stimulated Neovascularization, Inflammation Resolution and Collagen Maturation in Healing Rat Cutaneous Wounds by a Heparan Sulfate Glycosaminoglycan Mimetic, Otr4120. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:840–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giantsos KM, Kopeckova P, Dull RO. The Use of an Endothelium-Targeted Cationic Copolymer to Enhance the Barrier Function of Lung Capillary Endothelial Monolayers. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5885–5891. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giantsos-Adams K, Lopez-Quintero V, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J, Tarbell JM, Dull R. Study of the Therapeutic Benefit of Cationic Copolymer Administration to Vascular Endothelium under Mechanical Stress. Biomaterials. 2011;32:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coriat P, Guidet B, de Hert S, Kochs E, Kozek S, Van Aken H all co-signatories listed o. Counter Statement to Open Letter to the Executive Director of the European Medicines Agency Concerning the Licensing of Hydroxyethyl Starch Solutions for Fluid Resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:194–195. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oberleithner H, Riethmuller C, Schillers H, MacGregor GA, de Wardener HE, Hausberg M. Plasma Sodium Stiffens Vascular Endothelium and Reduces Nitric Oxide Release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacob M, Saller T, Chappell D, Rehm M, Welsch U, Becker BF. Physiological Levels of a-, B- and C-Type Natriuretic Peptide Shed the Endothelial Glycocalyx and Enhance Vascular Permeability. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:347. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0347-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chappell D, Bruegger D, Potzel J, Jacob M, Brettner F, Vogeser M, Conzen P, Becker B, Rehm M. Hypervolemia Increases Release of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Shedding of the Endothelial Glycocalyx. Critical Care. 2014;18:538. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]